Confucius, Socrates, and Saint Augustine: Philosophy

Absolutely! Let’s dive into the philosophies of Confucius, Socrates, and Saint Augustine, examining their core ideas, methodologies, and lasting impact on human thought and society:

Confucius (551-479 BCE):

- Focus: Ethics, social harmony, proper governance, and personal cultivation.

- Key Concepts:

- Ren (benevolence, compassion, humaneness): The fundamental virtue for individuals and rulers, promoting empathy and care for others.

- Li (ritual propriety): Following social norms, customs, and etiquette to maintain order and respect.

- Xiao (filial piety): Respect for elders and ancestors, seen as the foundation for a harmonious family and society.

- Junzi (noble person): The ideal individual who embodies moral virtues and strives for self-improvement.

- Legacy: Confucius’s teachings became the basis for Confucianism, a philosophy that profoundly shaped Chinese culture, government, and social values for over two millennia.

Socrates (470-399 BCE):

- Focus: Ethics, virtue, self-knowledge, and the pursuit of wisdom through questioning.

- Key Concepts:

- “The unexamined life is not worth living.” – This emphasizes the importance of self-reflection and critical thinking in leading a meaningful life.

- Socratic Method: A dialectical method of inquiry involving questioning and dialogue to uncover truths and challenge assumptions.

- Virtue as Knowledge: Socrates believed that true virtue is inseparable from knowledge and that no one knowingly does wrong.

- Legacy: Socrates’s philosophy laid the groundwork for Western philosophy, influencing figures like Plato and Aristotle. His emphasis on self-examination and the pursuit of wisdom continues to inspire critical thinkers today.

Saint Augustine (354-430 CE):

- Focus: Christian theology, the nature of God, the problem of evil, free will, and the relationship between faith and reason.

- Key Concepts:

- Original Sin: The belief that humanity inherited a flawed nature from Adam and Eve’s disobedience, leading to a propensity for sin.

- Divine Grace: The unmerited favor of God that enables salvation and overcomes the limitations of human will.

- The City of God: A contrast between the earthly city, characterized by sin and self-interest, and the heavenly city, where love of God reigns supreme.

- Legacy: Augustine’s writings profoundly shaped Christian theology and Western philosophy, addressing questions about human nature, morality, and the purpose of life. His works continue to be studied and debated today.

I hope this deeper look into the philosophies of these three influential thinkers is helpful! Feel free to ask if you have any further questions.

Confucius: “Sage” and “First Teacher”

Depiction of Confucius by Wu Daozi (685–758), Tang dynasty (Wiki Image).

| Years (BCE) | Age (approx.) | Events and Philosophical Focus | Key Concepts |

|---|---|---|---|

| 551-549 | 0-2 | Born in Lu state (modern Shandong province) during the Spring and Autumn period. | – Grew up in a time of political turmoil and social upheaval, which likely influenced his focus on restoring order and harmony. |

| 548-532 | 3-19 | Early life, education, and minor positions. | – Emphasis on learning and self-cultivation. |

| 532-527 | 20-24 | Begins teaching and attracting followers. | – Develop ideas on ritual (li), humaneness (ren), and the importance of moral character. |

| 527-517 | 25-34 | Travels throughout Lu and neighboring states seeking political office. | – Refines his philosophy of good governance based on moral principles and virtuous leadership. |

| 517-501 | 35-50 | Serves in minor government positions in Lu. | – Gains practical experience in administration and observes the challenges of implementing his ideals. |

| 501-497 | 51-54 | Appointed to high office in Lu; implements reforms with some success. | – Focuses on social harmony, justice, and the rectification of names (ensuring that words and actions align with reality). |

| 497-484 | 55-67 | Leaves Lu after political setbacks; travels extensively seeking patronage. | – Continues to refine his philosophy and teaching, emphasizing the importance of education, family, and tradition. |

| 484-479 | 68-72 | Returns to Lu; focuses on teaching and editing classic texts. | – Compiles and edits the Five Classics, which are essential works of Chinese literature and philosophy. |

| 479 | 72 | Dies in Lu. | – Leaves a legacy of profound philosophical and ethical teachings that have shaped Chinese culture and thought for millennia. |

EASTERN PHILOSOPHY – Confucius

(YouTube video)

Confucius (551–479 BCE), also known as Kongzi (Kǒng Fūzǐ), was a Chinese philosopher and teacher whose teachings have deeply influenced Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, and other East Asian cultures for over two millennia. He is traditionally considered the “Sage” and “First Teacher” of China.

Life and Work

Confucius was born in the state of Lu (modern-day Qufu, Shandong province) in a period of political and social disorder. He came from a noble but impoverished family and received a traditional education in the classics and rituals of Zhou Dynasty China.

Confucius worked in various government positions and traveled throughout China, advocating for his philosophical and political ideas. He believed moral leadership and social harmony were essential for a well-functioning society. He emphasized the importance of filial piety (respect for one’s parents and ancestors), social order, and individual responsibility.

Confucius’ teachings were not written down during his lifetime but were transmitted orally by his disciples. They were later compiled into a collection of texts known as the Analects.

Confucianism:

Confucianism is a complex system of thought encompassing philosophy, ethics, politics, and social life. It emphasizes

- Filial piety: Respect for one’s parents and ancestors.

- Ren (仁): Benevolence, humanity, or humaneness.

- Li (礼): Propriety, etiquette, or decorum.

- Junzi (君子): The “superior person” or the “exemplary person.”

- Xiao (孝): Filial piety

- Zhong (忠): Loyalty

- Shu (恕): Reciprocity or the Golden Rule

Legacy

Confucianism has had a profound impact on Chinese culture and society. It has shaped Chinese education, government, family structure, and social interactions. Confucian ideas have also influenced other East Asian cultures, such as Korea, Japan, and Vietnam.

Today, Confucianism continues to inspire many people in China and around the world. His teachings on ethics, morality, and social order remain relevant even in the 21st century.

Confucius’ Early Life and Background.

Confucius’ early life and background remain shrouded in mystery, as the most detailed accounts come from centuries after his death. However, there’s a general understanding of his origins based on available sources:

Birth and Family:

- Year: Confucius was born in 551 BCE in the state of Lu (present-day Qufu, Shandong province) in China.

- Family: His family belonged to the shi (士) class, between aristocracy and commoners.

- Ancestral lineage: Some historical accounts suggest Confucius descended from the dukes of Song, but their accuracy remains debated.

- Father: His father, Kong He (or Shuliang He), is believed to have been an elderly commandant in the local Lu garrison.

Education and Upbringing:

- Early education: Details are scarce, but he likely received education in classical texts, history, and rituals common for his social class.

- Focus on self-cultivation: Confucius emphasized lifelong learning and self-improvement, which may have been instilled in him early on.

- Financial constraints: His family faced financial difficulties, impacting his access to education and resources.

Early Jobs:

- Varied roles: During his early adulthood (20s-30s), Confucius held various government positions, such as bookkeeper and caretaker of livestock.

- Earning for family: These jobs likely served as a source of income to support his family, particularly after his father’s death.

- Seeking knowledge: Despite his work, Confucius continued his pursuit of knowledge and refined his understanding of culture, history, and rituals.

Turning Point:

- Death of his mother: The death of his mother when he was around 23 had a profound impact on him.

- Focus on mourning and rituals: He observed the traditional three-year mourning period, demonstrating his filial piety.

- Reflection and development: This period of reflection and immersion in rituals may have further shaped his philosophical views and interest in social order and moral conduct.

Overall, Confucius’ early life was likely marked by a combination of challenges and opportunities. Despite facing financial difficulties, he pursued education, held various jobs, and experienced personal losses that may have influenced his later philosophical and ethical teachings.

It is important to remember that the information available about Confucius’s early life comes from later sources and may be inaccurate. However, it can offer us a glimpse into the possible circumstances that shaped his early life and potentially contributed to his development as a philosopher.

Confucianism is a complex system of thought encompassing philosophy, ethics, politics, and social life.

Zengzi (right) kneeled before Confucius (center) in a painting from the Illustrations of the Classic of Filial Piety, Song dynasty (Wiki Image).

You’re absolutely right! Confucianism is a multifaceted philosophy that extends beyond just social norms. Here’s a breakdown of its key aspects:

Philosophy:

- Focus on ren (仁): Translated as benevolence, humanity, or humaneness, ren emphasizes compassion, empathy, and moral behavior towards others.

- Importance of li (礼): Often translated as propriety or etiquette, li refers to proper social conduct and adhering to traditional rituals and practices, ensuring smooth social interactions and upholding social order.

- Mean (中庸): The concept of “zhongyong” emphasizes finding the middle way or balance in all aspects of life, avoiding extremes in thought and behavior.

Ethics:

- Filial Piety (孝 xiao): As you mentioned, filial piety forms the cornerstone of Confucian ethics, emphasizing respect, obedience, and care towards one’s parents and ancestors.

- Reciprocity (恕 shu): This principle, similar to the Golden Rule, emphasizes treating others as you wish to be treated, fostering fairness and mutual respect within society.

- Five Constant Virtues (五常 wǔ cháng): These virtues, which form the foundation for ethical conduct, include benevolence (ren), righteousness (yi), propriety (li), wisdom (zhi), and fidelity (xin).

Politics:

- The Mandate of Heaven (天命 tiānmìng): This concept suggests that rulers derive their authority from the divine and must govern justly to maintain the mandate.

- Emphasis on meritocratic leadership: Confucius advocated for rulers to be chosen based on their moral character and ability to lead effectively rather than solely through hereditary succession.

- Importance of social order and harmony: Confucian thought emphasizes maintaining a well-defined social hierarchy with clear roles and responsibilities for individuals at different levels, contributing to social stability and harmony.

Social Life:

- Emphasis on family and community: Confucianism greatly emphasizes family values, social relationships, and fulfilling one’s role within the community.

- Education and self-cultivation: Confucius believed in the importance of lifelong learning and self-cultivation in becoming a moral and virtuous individual who contributes positively to society.

- Rituals and traditions: Observing traditional rituals and ceremonies plays a significant role in maintaining social order, honoring ancestors, and expressing respect within families and communities.

Confucianism continues to shape various aspects of life in China and many East Asian cultures. Its emphasis on ethical conduct, social harmony, and self-cultivation resonates with individuals and societies even today.

Confucius’ Focus on Ren

- “Real knowledge is to know the extent of one’s ignorance.” – This quote emphasizes the importance of humility and self-awareness in cultivating Ren. True compassion and empathy require understanding not only others but oneself and one’s limitations.

- “Do not impose on others what you yourself do not desire.” – This quote embodies the Golden Rule and highlights the core principle of treating others with the same respect and consideration you desire for yourself. This forms the basis for building genuine relationships and fostering a society built on ren.

- “Wherever you go, go with all your heart.” – This quote emphasizes dedication and sincerity in all endeavors. True ren extends beyond outward actions and requires genuine commitment and integrity in everything you do.

- “He who learns but does not think is lost. He who thinks but does not learn is in great danger.” – This quote stresses the importance of knowledge and reflection in cultivating ren. True understanding requires not just information but also critical thinking and applying knowledge to ethical situations.

- “Before you embark on a journey of revenge, dig two graves.” – This metaphor emphasizes the potential consequences of anger and resentment, which contradict the principles of ren. It encourages individuals to consider the potential harm they may bring upon themselves and others before seeking revenge.

Confucius’ focus on ren (仁), often translated as benevolence, humanity, or humaneness, is the cornerstone of his philosophy. It encompasses a complex set of virtues and ideals that guide individuals towards ethical conduct and contribute to a harmonious society.

Here’s a breakdown of the various aspects of ren in Confucianism:

- Empathy and compassion: Ren emphasizes understanding and caring for the feelings and well-being of others. This goes beyond mere politeness or kindness, requiring individuals to actively consider the impact of their actions on others and strive to alleviate suffering.

- Moral self-cultivation: Ren is not merely a passive state but an ongoing process of self-improvement. Individuals are encouraged to cultivate their moral character by reflecting on their actions, acknowledging their shortcomings, and striving to become better versions of themselves.

- Reciprocity and Golden Rule: Ren embodies the principle of “shu” (恕), often translated as reciprocity or the Golden Rule. It emphasizes treating others as you wish to be treated, fostering fairness and mutual respect within society.

- Propriety and etiquette (li 礼): While separate from ren, li plays a supporting role. Proper conduct and adhering to social norms demonstrate respect for others and contribute to a harmonious social order, ultimately supporting the practice of ren.

Examples of ren in action:

- A leader who uses their power to improve the lives of their people, not just for personal gain.

- A child who helps a needy classmate, even if it means sacrificing some personal convenience.

- A parent raises their children with love, discipline, and respect, instilling good moral values in them.

Significance of ren:

- Ren forms the foundation of Confucian ethics, providing a framework for ethical decision-making and guiding individuals toward virtuous behavior.

- By emphasizing ren, Confucius sought to promote social harmony and stability by encouraging individuals to treat each other with respect, compassion, and fairness.

- The concept of ren continues to be relevant today, offering valuable insights into building strong relationships, fostering responsible leadership, and creating a more just and compassionate society.

It is important to remember that ren is a multifaceted concept that has been interpreted and applied in various ways throughout history. However, its core message of cultivating compassion, self-improvement, and respect for others remains a valuable contribution to ethical thought.

Confucius’ Importance of li

- “Respect yourself, and others will respect you.” – This quote emphasizes the connection between li (propriety) and self-respect. By conducting oneself with dignity and adhering to proper behavior, one earns the respect of others, fostering harmonious social interactions.

- “Fine words and an insinuating appearance are seldom associated with true virtue.” – This quote highlights the importance of sincerity and authenticity within li. Proper behavior should not be a mere performance but a genuine expression of respect and consideration for others.

- “The superior man is modest in his speech, but exceeds in his actions.” – This quote emphasizes the balance between words and actions within li. True propriety requires speaking politely and demonstrating respect through one’s actions and deeds.

- “Guide them with policies and align them with punishments; the people will evade them and be ashamed. Guide them with virtue and align them with li, and the people will have a sense of shame and fulfill their roles.” – This quote contrasts the effectiveness of external controls and li in promoting appropriate behavior. By following li, individuals are motivated by a sense of internal responsibility and social harmony, leading to genuine fulfillment of their roles.

- “Wherever you go, observe the rites of that place.” – This quote emphasizes adaptability within li. While maintaining core principles of respectful conduct, li also encourages adjusting one’s behavior to align with the social norms and customs of different situations and contexts.

In his philosophical framework, Confucius emphasized li (礼), often translated as propriety, etiquette, or ritual. Li represents a set of formal social norms and practices that aim to cultivate order, harmony, and respect within society.

Here’s a breakdown of the critical aspects of li in Confucianism:

- Maintaining Social Order: Li establishes clear guidelines for behavior in different social situations and interactions. Following these guidelines ensures predictability, minimizes conflict, and fosters smooth social functioning.

- Respecting Hierarchies: Li emphasizes respecting established social hierarchies and fulfilling one’s role. This includes proper deference towards elders, superiors, and individuals of higher social standing.

- Rituals and Traditions: Observance of rituals and ceremonies plays a crucial role in li. These rituals, ranging from everyday greetings to elaborate ancestral ceremonies, serve as expressions of respect, reinforce social bonds, and transmit cultural values.

- Harmony and Aesthetics: Li is not merely about rigid rules but also incorporates aesthetic elements and aims to create a sense of grace, beauty, and elegance in social interactions.

Distinguishing li from ren:

While li and ren (benevolence) are interrelated concepts, they are distinct. Li focuses on the external forms of behavior and social interaction, while Ren emphasizes the inner qualities of compassion, empathy, and moral character. However, li is a concrete way to express ren in daily life. By acting in accordance with li, individuals demonstrate their respect for others and contribute to a society based on harmonious relationships and ethical conduct.

Criticisms and Modern Interpretations:

- Strict interpretations: Traditional interpretations of li have been criticized for being overly rigid and potentially hindering individual expression and creativity.

- Modern adaptations: In modern interpretations, the emphasis has shifted towards understanding the spirit and intention behind li rather than just following rigid rules. The focus is on adapting li to changing social contexts while still maintaining core values of respect, order, and social responsibility.

Examples of li in action:

- Greeting elders with a bow or handshake, depending on the cultural context.

- Dressing appropriately for different social occasions.

- Participating in traditional ceremonies and rituals with respect and sincerity.

- Use polite language and address others with proper titles.

Continuing Importance:

While evolving with changing times, the concept of li remains relevant in various Asian cultures. It emphasizes respecting cultural norms, maintaining social order, and engaging in interactions with grace and respect.

By understanding the meaning and purpose of li, individuals can contribute to building a more respectful, harmonious, and well-functioning society.

Confucius’ Mean

- “The superior man is modest in his speech but exceeds in his actions.” – This quote highlights the importance of balance and moderation in the Mean. While speaking humbly is recommended, taking action and demonstrating your capabilities through concrete effort is also crucial.

- “Wherever you go, go with all your heart.” – This quote emphasizes sincere commitment and avoiding extremes. Whether it’s pursuing knowledge or engaging in activities, the Mean encourages full dedication without neglecting other responsibilities or aspects of life.

- “Hold faithfulness and sincerity as first principles.” – This quote emphasizes honesty and genuineness as central aspects of the Mean. Avoiding extremes of deception or blind obedience requires practicing honesty and maintaining authenticity in your words and actions.

- “He who learns but does not think is lost! He who thinks but does not learn is in great danger.” – This quote highlights the importance of balancing knowledge and reflection. Neither acquiring information alone nor simply contemplating without learning from experience aligns with the Mean.

- “The course of the Mean lies midway between the two extremes.” – This straightforward quote summarizes the essence of the Mean. It emphasizes seeking a balanced approach in various aspects of life, avoiding the pitfalls of going to either extreme.

In Confucian philosophy, the Mean (中庸 zhōngyóng) holds a significant position, encouraging individuals to strive for moderation, balance, and avoiding extremes in thought and behavior. It is not a single rule or principle but rather a guiding compass for navigating life’s complexities.

Key aspects of the Mean:

- Finding balance: It emphasizes finding the middle ground between two opposing extremes. This applies to various aspects of life, such as emotions, actions, and social interactions.

- Avoiding extremes: The Mean discourages going to extremes in any aspect. For example, it advises against being overly assertive or overly passive, encouraging individuals to find a balance between these two extremes.

- Adaptability: The Mean is not a rigid set of rules but a flexible framework that adapts to different situations and circumstances. Finding the appropriate balance requires careful consideration of the context and individual circumstances.

- Harmonious living: Individuals aim to achieve harmony within themselves and with society by striving for the Mean. This fosters a sense of peace, order, and well-being.

The Mean in Practice:

- A leader who balances decisiveness with being open to feedback.

- A student who works hard and allows time to relax and recharge.

- A parent who demonstrates both love and discipline towards their children.

Relationship to other Confucian concepts:

- The Mean complements ren (benevolence) by promoting the compassionate consideration of others when making choices.

- It aligns with li (propriety) by encouraging individuals to follow social norms and act appropriately, promoting social harmony.

Criticisms and modern interpretations:

- Critics argue that the Mean can be interpreted as promoting conformity and hindering individual expression.

- Modern interpretations emphasize flexibility and contextual understanding, acknowledging that the meaning of “middle ground” can vary depending on the situation and individual values.

The Mean’s continuing relevance:

The concept of the Mean offers valuable guidance in navigating life’s complexities. It encourages us to seek balance, avoid extremes, and strive for a harmonious, adaptable, and ethically sound life.

Remember: The Mean is not a destination but a continuous process of self-reflection, adaptation, and striving for balance in a constantly changing world.

Confucius’ Filial Piety

- “Respect yourself, and others will respect you.” (This quote emphasizes the connection between filial piety and self-respect, suggesting that treating oneself well is foundational to treating others respectfully.)

- “The father who does not teach his son his duties is equally guilty with the son who neglects them.” (This quote highlights the shared responsibility between parents and children in upholding filial piety.)

- “When a man’s father is alive, observe his intentions. After his father is no more, observe his actions. If he does not change his father’s ways for three years, he is worthy to be called filial.” (This quote emphasizes the importance of continuing one’s parents’ values and traditions after their passing, demonstrating ongoing filial respect.)

- “While parents are alive, do not inquire about their death. While your wife is alive, do not inquire about her place in the other world.” (This quote conveys the importance of living in the present and focusing on honoring your parents while they are still alive rather than dwelling on the future or the afterlife.)

- “Zigong asked: ‘Is there one word that can be practiced throughout one’s life?’ The Master replied: ‘Perhaps the word ‘shu’ (reciprocity) will do: Do not do to others what you do not want others to do to you.'” (This quote connects the principle of filial piety to the broader concept of reciprocity, suggesting that treating others with respect and consideration is an extension of honoring your parents and maintaining social harmony.)

Filial piety (xiao 孝) is a cornerstone of Confucianism. It emphasizes respect, obedience, and care for one’s parents and ancestors. Confucius believed filial piety was a core family value and the foundation for a harmonious society.

Core aspects of filial piety in Confucianism:

- Respect: Showing deference and respect to parents and elders through actions and words.

- Obedience: Following the guidance and instructions of parents unless they violate moral principles.

- Care: Providing for parents’ physical and emotional needs, especially as they age.

- Ancestral veneration: Honoring and remembering deceased ancestors through rituals and offerings.

Beyond individual families:

Confucius extended the concept of filial piety beyond individual families. He believed it served as a model for social order and hierarchy. By respecting and obeying one’s parents, individuals learn to respect and obey those in positions of authority, contributing to a stable and orderly society.

Criticisms and Modern Interpretations:

- Strict interpretations: Critics argue that traditional interpretations of filial piety can be overly rigid and limit individual autonomy, particularly for women.

- Modern interpretations: In modern times, the emphasis has shifted from blind obedience to mutual respect and understanding within families while still retaining the core values of care, respect, and responsibility.

Examples:

- Listening to your parents’ advice.

- Helping your parents with household chores.

- Take care of your parents as they age.

- Visit and honor the graves of your ancestors.

Continuing Importance:

While evolving, filial piety remains influential in many Asian cultures. It encourages individuals to prioritize family relationships, respect elders, and contribute to a harmonious society. While interpretations and practices may adapt to changing times, the core values of filial piety continue to resonate with many people.

Confucius’ Reciprocity

- “Do not impose on others what you yourself do not desire.” – This quote directly reflects the Golden Rule and captures the essence of reciprocity. It encourages individuals to treat others with the same respect and consideration they desire for themselves, forming the foundation of ethical interactions.

- “Before you embark on a journey of revenge, dig two graves.” – This metaphorical quote highlights the potential consequences of anger and resentment, which contradict the principle of reciprocity. It encourages individuals to consider the potential harm they might bring to themselves and others before engaging in harmful actions.

- “The superior man is distressed by the limitations of his ability; he is not distressed by the fact that men do not recognize the ability that he has.” – This quote emphasizes the importance of focusing on self-improvement and fulfilling one’s responsibilities within the framework of reciprocity. True ethical conduct stems from within, not seeking external validation.

- “Wherever you go, observe the rites of that place.” – While seemingly unrelated to reciprocity at first glance, this quote highlights the importance of adapting one’s behavior to consider the perspectives and values of others. This aligns with reciprocity by encouraging individuals to respect different situations’ social norms and customs, fostering mutual understanding and cooperation.

- “The superior man is distressed by the limitations of his ability; he is not distressed by the fact that men do not recognize the ability that he has.” – This quote, while seemingly repeating a previous one, reinforces the idea that genuine compassion and empathy, central aspects of reciprocity, stem from within. True concern for others’ well-being goes beyond external recognition or seeking reciprocation.

In Confucian philosophy, the principle of reciprocity (恕 shu), also known as the Silver Rule, is crucial in guiding ethical conduct and fostering harmonious relationships. It emphasizes treating others the way you wish to be treated.

Understanding the concept:

- Golden Rule Comparison: Reciprocity shares similarities with the Golden Rule, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” which is found in various cultures and philosophies. However, the Silver Rule adds a layer of introspection and self-awareness.

- Focus on Self-Reflection: Before considering how to treat others, individuals are encouraged to reflect on how they would like to be treated themselves in similar situations. This fosters empathy and understanding.

Putting reciprocity into practice:

- Empathy and Consideration: Individuals are encouraged to approach interactions with empathy, considering the other person’s perspective, feelings, and desires.

- Fairness and Respect: Reciprocity promotes treating others fairly, even if they haven’t treated you the same way.

- Building Trust and Cooperation: By acting with reciprocity, individuals can build trust and cooperation with others, contributing to a more harmonious society.

Examples of reciprocity in action:

- Helping a colleague with a task because you would appreciate their help if you were in the same situation.

- Apologizing for your mistakes, acknowledging that you wouldn’t want someone else to be treated unfairly.

- Showing respect and kindness to someone in a service position, recognizing they deserve to be treated with dignity.

Significance of reciprocity:

- Foundation for ethical conduct: Reciprocity provides a framework for ethical decision-making, guiding individuals towards actions that are fair, considerate, and ultimately beneficial for society.

- Promoting social harmony: Individuals can contribute to a more peaceful and harmonious social environment by treating each other with respect and empathy.

- Universality and Relevance: The principle of reciprocity transcends cultural and religious boundaries, offering a valuable ethical guide applicable to various situations and relationships.

Criticisms and modern interpretations:

- Potential for exploitation: Some argue that reciprocity can be misinterpreted, allowing individuals to justify treating others poorly if they have been treated poorly themselves.

- Understanding different perspectives: Modern interpretations emphasize the importance of understanding the cultural and social contexts of others to ensure that acting reciprocally doesn’t inadvertently cause harm or disrespect.

Confucius’ concept of reciprocity remains a significant contribution to ethics and social interaction. Encouraging individuals to treat others with the same respect, empathy, and fairness they desire for themselves lays the foundation for building stronger relationships and fostering a more harmonious society.

Confucius’ Five Constant Virtues

- “Real knowledge is to know the extent of one’s ignorance.” (Ren) – This quote emphasizes the importance of humility and self-awareness in cultivating ren (benevolence). True compassion and empathy require understanding not only others but also oneself and one’s limitations.

- “Do not impose on others what you yourself do not desire.” (Yi) – This quote embodies the Golden Rule and highlights the core principle of treating others with the same respect and consideration you desire for yourself. This forms the basis for building genuine relationships and fostering a society built on yi (righteousness).

- “The superior man is modest in his speech, but exceeds in his actions.” (Li) – This quote emphasizes the balance between words and actions within li (propriety). True respect goes beyond pronouncements, requiring individuals to demonstrate their sincerity through their deeds.

- “He who learns but does not think is lost. He who thinks but does not learn is in great danger.” (Zhi) – This quote stresses the importance of both knowledge and reflection in cultivating zhi (wisdom). True understanding requires information, critical thinking, and applying knowledge to real-world situations.

- “Hold faithfulness and sincerity as first principles.” (Xin) – This quote emphasizes honesty and genuineness as central aspects of xin (trustworthiness). Building trust requires individuals to be reliable in their words and actions, adhere to their promises, and demonstrate consistency in their character.

Confucius emphasized five core virtues, collectively known as the Five Constant Virtues (五常 wǔ cháng), that serve as the foundation for ethical conduct and social harmony in his philosophy. These virtues are:

- Ren (仁) – Benevolence or Humanity: This central virtue refers to compassion, empathy, and a genuine concern for the well-being of others. It involves going beyond self-interest and actively seeking to benefit others.

- Yi (义) – Righteousness or Justice: Yi emphasizes acting in accordance with moral principles, upholding the right, and standing up for what is just, even when it’s difficult. It involves adhering to moral codes and acting with integrity.

- Li (礼) – Propriety or Etiquette: Li refers to proper conduct and social norms. It encompasses respecting established traditions, following rituals, and behaving appropriately in different social situations. Li contributes to social order, and fosters respect for others.

- Zhi (智) – Wisdom or Knowledge: Zhi emphasizes the importance of acquiring knowledge, understanding the world around us, and using this knowledge to make wise decisions. It involves learning from experience, reflecting critically, and making sound judgments.

- Xin (信) – Trustworthiness or Fidelity: Xin highlights the importance of keeping one’s promises, being honest and reliable, and building trust with others. It involves staying true to your word, acting with integrity, and being dependable.

Interconnectedness of the Virtues:

These virtues are not isolated concepts but are interconnected and reinforce each other. For example, practicing ren (benevolence) requires acting with yi (righteousness) and li (propriety). Similarly, demonstrating zhi (wisdom) helps individuals make decisions that align with the other virtues.

The Five Constant Virtues and Modern Relevance:

While originally developed within a specific cultural context, the core values embedded in the Five Constant Virtues continue to hold significance in the modern world. They offer valuable guidance for ethical conduct, fostering positive relationships, and contributing to a more just and harmonious society.

Here are some additional points to consider:

- The interpretation and application of these virtues can vary depending on cultural context and individual perspectives.

- The Five Constant Virtues continue to be debated and studied by scholars and individuals interested in Confucian philosophy and ethics.

- Understanding these virtues can provide valuable insights into building a more ethical and compassionate world.

I hope this explanation provides a comprehensive overview of Confucius’ Five Constant Virtues.

Confucius’ The Mandate of Heaven

- “The decree of Heaven is unpredictable. Like the movement of the sun and moon, it cannot be stopped.” – This quote highlights the unpredictable nature of the Mandate of Heaven, emphasizing that it is not guaranteed and can be lost through immoral leadership or neglecting the needs of the people.

- “He who gains the confidence of the multitudinous people will be Emperor.” – This quote connects the Mandate of Heaven to public approval. It suggests that a ruler’s legitimacy stems from divine selection and from earning the trust and support of the people they govern.

- “When a prince’s personal conduct is correct, then right principles will prevail throughout the country.” – This quote emphasizes the role of moral leadership in fulfilling the Mandate of Heaven. A virtuous and just ruler sets a positive example and ensures the well-being of the people, solidifying their claim to the Mandate.

- “To see what is right and not to do it is want of courage.” – This quote, while not directly related to the Mandate of Heaven, emphasizes the importance of taking action in accordance with ethical principles. Leaders entrusted with the Mandate are expected to act courageously and make decisions for the good of the people, even when it’s difficult.

- “The superior man is distressed by the limitations of his ability; he is not distressed by the fact that men do not recognize the ability that he has.” – This quote, though seemingly unrelated, highlights the inner responsibility associated with the Mandate of Heaven. True leaders focus on fulfilling their duties with competence and integrity, not seeking external validation or recognition.

In Confucian political philosophy, the Mandate of Heaven (天命 tiānmìng) served as a powerful justification for rulers’ legitimacy. It wasn’t just political theory; it held significant cultural and religious weight, shaping the dynamics of power and the expectations of rulers and the ruled in ancient China.

Key aspects of the Mandate of Heaven:

- Divine Origin: The concept suggests that heaven (Tian) bestows the right to rule upon a virtuous and capable leader. This leader is then referred to as the “Son of Heaven” (天子 tiānzǐ), signifying their divinely sanctioned authority.

- Conditional Mandate: The Mandate of Heaven was not unconditional. It was believed that rulers who lost the way (道 dào), meaning they became corrupt, lost the public’s trust, or failed to govern effectively, would lose the Mandate and face potential rebellion or natural disasters, interpreted as signs of heavenly disapproval.

- Legitimizing Power: The Mandate of Heaven provided a powerful justification for existing dynasties and offered a moral framework for leadership, encouraging rulers to govern justly and prioritize the welfare of their people.

The Mandate of Heaven in practice:

- Rise and Fall of Dynasties: Throughout Chinese history, dynasties rose and fell, often justified by narratives framing the new rulers as possessing the Mandate and the previous ones as having lost it.

- Moral Exemplars: Rulers were expected to embody Confucian virtues such as benevolence, righteousness, and proper conduct, demonstrating their worthiness of the Mandate.

- Social Order and Stability: The concept helped maintain social order and stability by providing a framework for legitimate rule and discouraging rebellion against divinely chosen leaders.

Criticisms and modern interpretations:

- Questioning Legitimacy: Critics argue that rulers could manipulate the Mandate of Heaven to maintain power regardless of their actual conduct.

- Limited Relevance in Modern Times: With the rise of modern political systems based on secular principles like democracy, the Mandate of Heaven has limited direct relevance in contemporary China.

However, its legacy continues to be felt:

- Cultural Influence: The concept remains embedded in Chinese cultural consciousness and influences perceptions of leadership and social responsibility.

- Moral Compass: The emphasis on virtuous leadership and prioritizing the well-being of the people still holds value in the modern world, even if the divine justification is no longer prevalent.

In conclusion, the Mandate of Heaven was a significant concept in Confucian political thought. It legitimized rulers, shaped leadership expectations, and influenced the course of Chinese history. While its direct application might have waned in the modern era, its legacy resonates in various ways.

Confucius’ Emphasis on meritocratic leadership

- “In a well-governed state, the people are valued; in a poorly governed state, goods are valued.” – This quote highlights Confucius’ belief that a good leader prioritizes the well-being of the people, not just material wealth. Valuing the people implies selecting leaders based on their qualities and abilities to serve the public good, reflecting the essence of meritocratic leadership.

- “Let there be no virtuous man who is unemployed, and no official who is not virtuous.” – This quote emphasizes the importance of matching talent and virtue with leadership positions. It suggests that individuals who possess the necessary qualities, such as morality, competence, and leadership skills, should be entrusted with leadership roles, regardless of their social status or background.

- “The superior man is distressed by the limitations of his ability; he is not distressed by the fact that men do not recognize his ability.” – This quote highlights the focus on inner responsibility and self-improvement in meritocratic leadership. True leaders, even those not formally recognized, strive to cultivate their abilities and act with integrity, demonstrating their value through their actions.

- “Wherever you go, observe the rites of that place.” – While seemingly unrelated, this quote emphasizes adaptability and understanding the needs of the people. A good leader, chosen based on merit, can adapt their approach to different situations and contexts while upholding core principles of good governance, reflecting the need for flexibility and responsiveness in leadership.

- “Real knowledge is to know the extent of one’s ignorance.” – This quote emphasizes the importance of humility and self-awareness, crucial qualities for meritocratic leaders. Recognizing limitations allows leaders to seek advice, learn from others, and continuously improve their abilities to serve people effectively.

While advocating for a hierarchical social order, Confucius emphasized meritocratic leadership as a key element to ensure a just and harmonious society. Here’s what we know about his perspective:

Rejection of Hereditary Rule:

- Confucius was critical of the traditional system of hereditary succession, where leadership positions passed solely through familial lineage.

- He believed such a system could result in incompetent and immoral leaders, potentially harming the people’s well-being.

Importance of Merit:

- Confucius advocated for selecting leaders based on their merit. This included moral character, competence, knowledge, and leadership abilities, not just noble birth.

- He believed individuals with these qualities were best equipped to govern effectively, make wise decisions, and act in the people’s best interests.

Examples and Impact:

- While Confucius never held an official position himself, his ideas influenced various rulers and political thinkers throughout Chinese history.

- The concept of civil service examinations, where individuals competed for government positions based on their knowledge and abilities, emerged partly due to the influence of Confucian thought.

- The emphasis on meritocratic leadership continues to be relevant in various contexts, influencing discussions about egalitarianism, social mobility, and good governance in the modern world.

Criticisms and Considerations:

- Critics argue that defining and measuring merit can be subjective and potentially biased, leading to inequalities in the selection process.

- The focus on merit can also downplay the importance of experience and practical skills that may not be easily measured through examinations or standardized assessments.

Confucianism’s emphasis on meritocratic leadership offered an alternative to hereditary systems, promoting the idea that leadership should be entrusted to those who possess the necessary qualities to serve the public good effectively. While the concept has its limitations and complexities, it continues to spark discussions about ethical leadership and good governance in the contemporary world.

Confucius’ Importance of Social Order and Harmony

- “Wherever you go, go with all your heart.” – This quote emphasizes dedication and commitment to social order and harmony. It encourages individuals to fully engage in their roles and responsibilities, contributing to the collective well-being.

- “He who learns but does not think is lost. He who thinks but does not learn is in great danger.” – This quote stresses the importance of knowledge and reflection in maintaining social order and harmony. Understanding social norms and principles while critically reflecting on their application allows for adaptation and effective participation within the social order.

- “Respect yourself, and others will respect you.” – This quote highlights the reciprocal nature of social order and harmony. By acting respectfully and fulfilling your role, you contribute to a climate of mutual respect, strengthening social bonds and promoting cooperation.

- “The superior man is modest in his speech but exceeds in his actions.” – This quote emphasizes the importance of authenticity and sincerity within the social order. True adherence to social norms goes beyond simply following rules; it requires genuine respect and consideration for others, demonstrated through one’s actions and deeds.

- “Before you embark on a journey of revenge, dig two graves.” – This metaphor emphasizes the potential consequences of disrupting social order through harmful actions like revenge. It encourages individuals to consider the negative effects of their actions on themselves and others, promoting peaceful conflict resolution and fostering harmony.

Social order and harmony, also known as “he (和)” in Chinese, was a central pillar of Confucius’ philosophy. He believed that a well-functioning society required individuals to fulfill their roles, adhere to social norms, and prioritize cooperation and mutual respect to achieve a state of peace and prosperity.

Here’s a deeper look into why social order and harmony held such significance for Confucius:

Benefits of Social Order:

- Stability and Security: Confucius viewed a structured social order, with everyone fulfilling their designated roles, as essential for maintaining societal stability and security. This stability, in turn, allowed individuals to pursue their goals and contribute to the collective well-being.

- Reduced Conflict: A clear understanding of social roles and responsibilities helped minimize conflict and ensure predictable social interactions. This fostered a sense of trust and cooperation, crucial for building a harmonious community.

- Effective Governance: Confucius believed that adhering to social order enabled effective governance. When everyone understood their roles and responsibilities, leaders could focus on ensuring the entire society’s well-being.

Achieving Harmony through Ren (仁):

- Beyond Order: Confucius’ vision went beyond just establishing order; he emphasized achieving harmony (he) within that order. This harmony was cultivated through ren (仁) or benevolence. Ren encouraged individuals to treat others with compassion, empathy, and respect, fostering mutual understanding and cooperation.

- Fulfilling Roles with Ren: Fulfilling one’s designated role in society wasn’t just about following rules but doing so with goodwill and consideration for others. This fostered a sense of collective responsibility and contributed to a more harmonious social environment.

Criticisms and Modern Considerations:

- Potential for Inflexibility: Critics argue that emphasizing social order could lead to inflexibility and hinder social progress. It may not adequately acknowledge the need for individual expression and adaptation to changing circumstances.

- Evolution of Social Order: The rigid social hierarchies envisioned by Confucius have evolved significantly in modern societies, with increasing emphasis on individual rights and equality.

- Relevance in Modernity: Despite these changes, the core values of mutual respect, cooperation, and social responsibility remain relevant in navigating the complexities of modern social interactions.

Conclusion:

Confucius’ emphasis on social order and harmony continues to influence various aspects of East Asian societies. While the specific interpretations and applications may have evolved, the underlying values of fostering a peaceful, cooperative, and well-functioning society offer valuable insights for navigating the complexities of social interactions, even in the modern world.

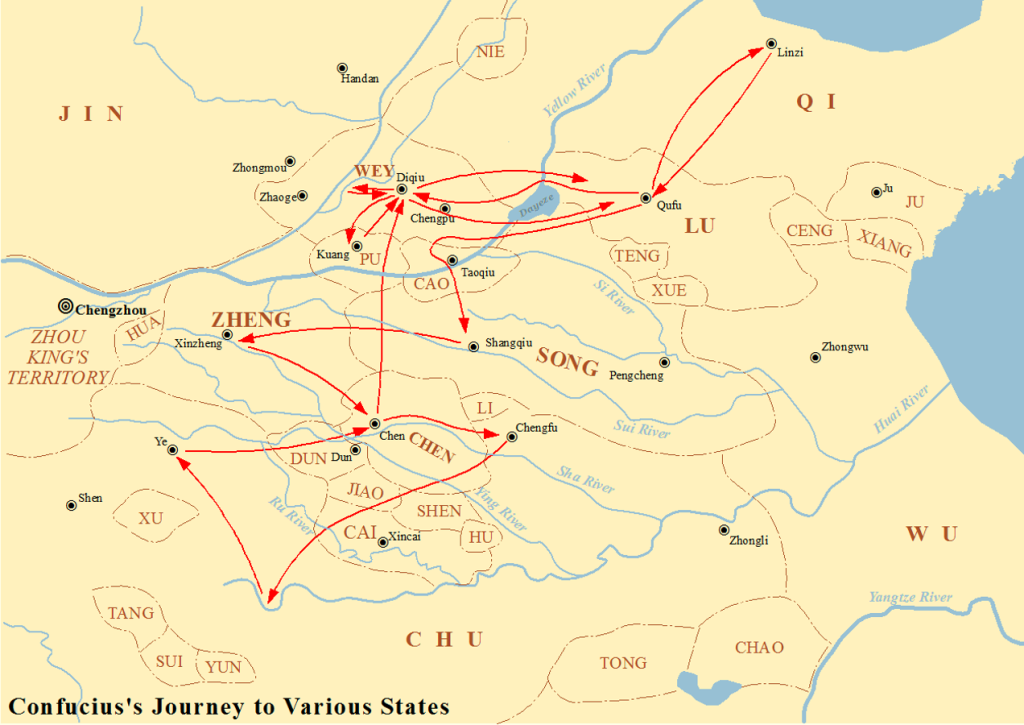

Confucius’ Exile

Map showing the journey of Confucius to various states between 497 BCE and 484 BCE (Wiki Image).

Though a period shrouded in some ambiguity, Confucius’ exile holds significant meaning in understanding his life and philosophy. Here’s what we know:

Context:

- Timeframe: The exact date of Confucius’ departure from his home state of Lu is debated, but it likely occurred between 497 BCE and 484 BCE.

- Age: He was in his late 50s or early 60s.

Reasons for Exile:

- Failed political reforms: Confucius held various government positions in Lu and advocated for social and political reforms based on his ethical principles. However, these reforms faced opposition from powerful families within the state.

- Frustration and disillusionment: Facing resistance and lack of progress, Confucius and his disciples left Lu, seeking a ruler to implement his ideas.

Nature of the Exile:

- Voluntary or involuntary: Some scholars argue that Confucius actively sought an opportunity to put his ideas into practice elsewhere, while others believe he felt forced to leave due to political pressure.

- Travels and experiences: Confucius, accompanied by a group of loyal disciples, traveled throughout various Chinese states for 14 years. They engaged in discussions with rulers and scholars, but Confucius ultimately failed to find a ruler receptive to his vision.

Impact of the Exile:

- Disappointment and reflection: The exile experience likely caused Confucian disappointment and frustration. However, it also allowed him to develop his philosophy further and refine his ideas through dialogue and interaction with different cultural perspectives.

- Spread of his ideas: His travels allowed him to disseminate his teachings in different regions, impacting a wider audience and laying the groundwork for Confucianism’s future influence.

Return and Final Years:

- Despite the challenges of exile, Confucius eventually returned to Lu in his late 60s.

- He continued teaching and writing, contributing significantly to the development of Confucian philosophy.

- He died in 479 BCE, leaving a lasting legacy that has shaped Chinese culture and society for centuries.

Conclusion:

While the specifics of Confucius’ exile remain unclear, it serves as a reminder of his dedication to his ideals and his efforts to find a receptive audience for his vision of a just and harmonious society. The experience likely shaped his perspective and contributed to the enduring influence of his teachings.

It’s important to note that historical accounts of Confucius’ life and exile can vary, and there is ongoing debate about the details. However, the core message of his dedication to his beliefs and his efforts to create a better world through education and moral conduct remain significant.

Confucianism has shaped Chinese education, government, family structure, and social interactions. His ideas have also influenced other East Asian cultures, such as Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, and teachings on ethics, morality, and social order remain relevant even in the 21st century.

The Temple of Confucius in Jiading is now a suburb of Shanghai. The Jiading Temple of Confucius now operates a museum devoted to the imperial exam formerly administered at the temples (Wiki Image).

You’ve provided an excellent summary of Confucianism’s lasting influence! Here are some additional points to consider:

Education:

- Emphasis on classics and moral teachings: Confucian education traditionally focused on studying classical texts like the Analects and learning proper ethical conduct.

- Civil service examinations: For centuries, China’s government selection process relied heavily on examinations based on Confucian principles.

- Modern adaptations: While rote memorization has lessened, core Confucian values of respect, diligence, and social responsibility are instilled in Chinese education systems.

Government:

- Bureaucracy and meritocracy: Confucianism’s emphasis on social order and hierarchy influenced the development of a strong centralized bureaucracy in China.

- Rulers as moral exemplars: Leaders were expected to embody Confucian virtues and govern justly to maintain social harmony and the Mandate of Heaven.

- Modern influence: Echoes of Confucian thought can be seen in some East Asian governments’ emphasis on social stability and prioritization of collective well-being.

Family Structure:

- Patriarchal hierarchy: Confucianism traditionally emphasized a patriarchal family structure with the father as the head of the household.

- Importance of filial piety: Respect for elders and fulfilling familial obligations remain crucial aspects of family life in many East Asian cultures.

- Modernization and adaptations: Changing social structures and gender roles lead to a gradual shift towards more egalitarian family dynamics while valuing respect for elders and family ties.

Social Interactions:

- Emphasis on social harmony and respect: Confucianism promotes maintaining social order and treating others with respect based on their societal position.

- Guanxi (关系 guānxì): The concept of guanxi, emphasizing building relationships and reciprocity, is deeply rooted in Confucian ideas of social interaction.

- Modern challenges: Balancing traditional respect hierarchies with modern values of individual expression and social equality can be challenging in some societies.

Overall, Confucianism continues to significantly influence various aspects of life in China and other East Asian cultures. While adapting to the modern world, its core principles of ethical conduct, social responsibility, and harmonious relationships remain relevant and contribute to the unique social fabric of these regions.

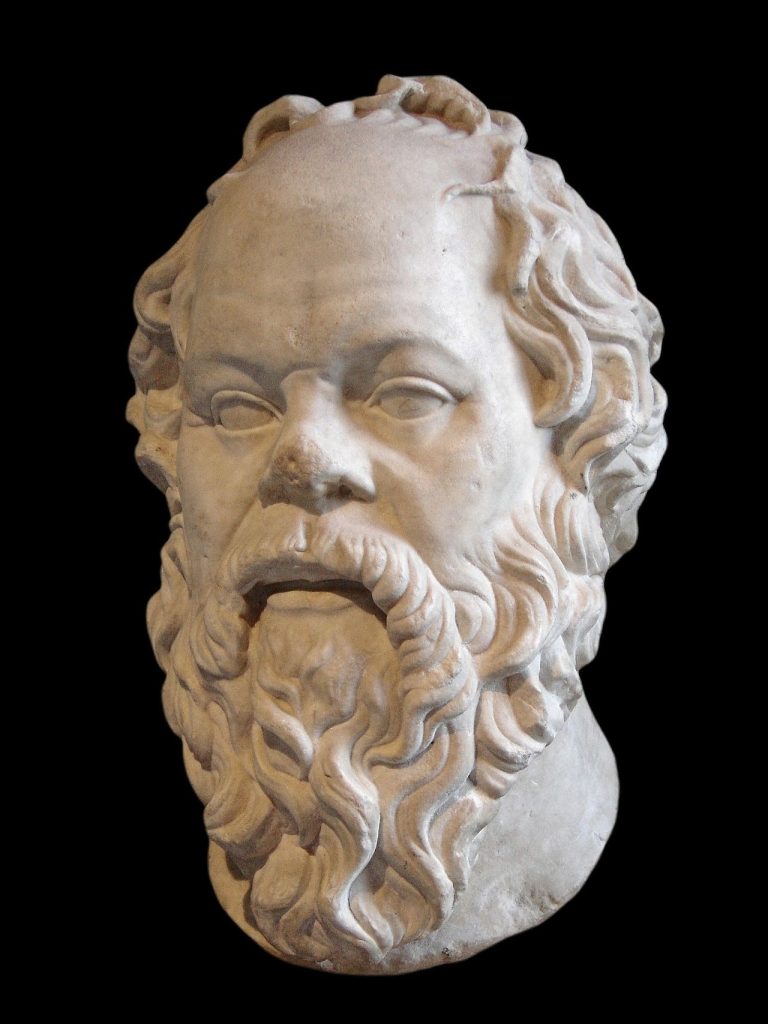

Socrates: The Father of Western Philosophy

A marble head of Socrates in the Louvre (copy of bronze head by Lysippus) (Wiki image).

| Years (BCE) | Age (approx.) | Events and Philosophical Focus | Key Concepts and Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| 469-450 | 0-19 | Born in Athens; Early Life. | – Likely received a traditional education. |

| 450-430 | 20-39 | Develops interest in philosophy; begins questioning traditional beliefs. | – Questions about virtue, justice, piety, and knowledge. |

| 430-420 | 40-49 | Serves as a soldier in the Peloponnesian War. | – Demonstrates courage and resilience in battle. |

| 420-400 | 50-69 | Becomes renowned for his philosophical discussions in the Athenian marketplace (Agora). | – Engages in dialectic (question-and-answer method) to expose contradictions and arrive at truth. |

| 420-400 | 50-69 | Gains followers, including Plato, face criticism for challenging conventional wisdom. | – Emphasizes self-examination (“Know thyself”) and pursuing virtue as the highest good. |

| 400 | 69 | Accused of impiety and corrupting the youth, put on trial. | – Defends his philosophical pursuit; found guilty and sentenced to death. |

| 400 | 69 | He dies by drinking hemlock. | – His death becomes a symbol of philosophical martyrdom. |

Classical Greek Philosophy: Socrates and Plato

(YouTube video)

Socrates (c. 470 – 399 BCE) was a Greek philosopher widely considered the founder of Western philosophy. He was renowned for his Socratic method, a unique approach to teaching and learning that involved asking thought-provoking questions to stimulate critical thinking and lead individuals to their understanding of truth.

Here’s a glimpse into his life and legacy:

- Early Life and Influences: Born in Athens, Greece, Socrates was the son of a stonemason and a midwife. He may have been influenced by pre-Socratic philosophers like Thales and Parmenides but developed his distinctive approach to philosophical inquiry.

- Approach to Philosophy: Socrates didn’t believe in simply transmitting knowledge but in challenging existing beliefs and encouraging individuals to think critically. He often engaged in public dialogues, questioning assumptions and provoking self-reflection in his interlocutors.

- Legacy: Despite writing nothing himself, Socrates profoundly influenced Western thought through his students, particularly Plato and Xenophon. His ideas on ethics, knowledge, and the importance of self-examination continue to resonate with philosophers and individuals seeking a deeper understanding of themselves and the world around them.

- Trial and Death: Controversial figures often mocked him in Athenian comedies. Accused of impiety (disrespect for the gods) and corrupting the youth, he was sentenced to death by hemlock poisoning in 399 BCE. He chose to accept the verdict rather than flee or compromise his principles, showcasing his unwavering commitment to his beliefs.

Socrates’ legacy extends beyond philosophy:

- He is considered a champion of critical thinking and intellectual inquiry.

- His Socratic method remains a valuable tool for education and facilitating self-discovery.

- He serves as a reminder of the importance of questioning authority and upholding one’s convictions.

Feel free to ask if you’d like to explore specific aspects of Socrates’ life, philosophy, or legacy!

Socrates’ Early Life and Influences

Battle of Potidaea (432 BC): Athenians against Corinthians (detail). Scene of Socrates (center) saving Alcibiades. 18th century engraving. According to Plato, Socrates participated in the Battle of Potidaea, the retreat of the Battle of Delium, and the Battle of Amphipolis (422 BC) (Wiki Image).

While little definitive information exists about Socrates’ early life, historians and scholars have pieced together some details and potential influences:

Family and Background:

- Born in Athens around 470 BCE, Socrates was the son of Sophroniscus, a stonemason, and Phaenarete, a midwife. While not considered wealthy or belonging to the noble class, they provided him with a basic education.

- It’s unclear if he directly learned his father’s trade, but some accounts suggest he might have received training in sculpture.

Early Influences:

- During his formative years, Athens underwent intellectual and cultural flourishing. He likely encountered various philosophical ideas circulating then, including

- Pre-Socratic philosophers: Early thinkers like Thales and Anaxagoras focused on natural world inquiry and questioning traditional explanations.

- Sophists: A group of traveling teachers known for emphasizing rhetoric, critical thinking, and challenging conventional beliefs.

- Socrates was likely exposed to these diverse perspectives, laying the groundwork for his unique approach to philosophy.

Developing His Method:

- While details are limited, it’s believed that Socrates did not formally study with any specific teacher. Instead, he developed his approach to philosophy through interactions and dialogues with diverse individuals in Athenian society.

- This included engaging with artisans, politicians, poets, and everyday people, asking questions, and challenging their assumptions. This constant questioning and examination of ideas eventually became the foundation of his renowned “Socratic method.”

Uncertainties and Ongoing Study:

It’s important to remember that much of what we know about Socrates comes from later writers, primarily his student Plato. Historians continue to debate the accuracy and reliability of these accounts.

If you’re interested in specific aspects of Socrates’ early life, like his potential interactions with other philosophers or the political and cultural context of the time, feel free to ask!

Socrates didn’t believe in transmitting knowledge but rather in challenging existing beliefs and encouraging individuals to think critically. He often engaged in public dialogues, questioning assumptions and provoking self-reflection in his interlocutors.

The Debate of Socrates and Aspasia by Nicolas-André Monsiau. Socrates’s discussions were not limited to a small elite group; he engaged in dialogues with foreigners and people from all social classes and genders (Wiki image).

Absolutely! This statement captures the heart of the Socratic method. Here’s why it’s important and how it worked:

Knowledge is Within: Socrates believed that true knowledge wasn’t something to be passively absorbed. He felt that real understanding comes from within. His goal was to guide individuals toward this inner knowledge through relentless questioning and dialogue.

Question Everything: Socrates challenged conventional beliefs and assumptions to uncover this inner wisdom. He’d ask open-ended and thought-provoking questions, making his conversation partners examine their reasoning.

Elenchus: The Socratic method is sometimes called the “elenchus,” a Greek word meaning “refutation” or “cross-examination.” It often involved pointing out inconsistencies or flawed logic in the beliefs of the person he spoke with.

Intellectual Midwife: Socrates compared himself to a midwife, drawing parallels to how midwives assist in childbirth. Through his questioning, he believed he was aiding others in ” giving birth” to their own understanding.

The Impact:

- Critical Thinking: This approach fostered critical thinking and intellectual independence. It pushed people to justify their beliefs and consider alternative perspectives.

- Self-awareness: By revealing flaws in their thinking, individuals could gain self-awareness and re-evaluate what they thought they knew.

- Foundations of Philosophy: This method laid the foundation for today’s philosophical tradition. The quest for knowledge and critical reasoning remain core elements of philosophical thought.

Let me know if you’d like to explore any aspect of this further!

Despite writing nothing himself, Socrates profoundly influenced Western thought through his students, particularly Plato and Xenophon.

Alcibiades’ Receiving Instruction from Socrates is a 1776 painting by François-André Vincent depicting Socrates’s daimon (Wiki Image).

Your statement accurately summarizes the lasting impact of Socrates on Western thought. He did not leave any written works directly from him, but his teachings and philosophies lived on through the writings of his students, especially Plato and Xenophon. Here are some additional points to consider:

- The Socratic Method: This unique dialogue-based approach to learning, in which Socrates asked probing questions to challenge assumptions and encourage critical thinking, remains influential in education and various fields.

- Focus on Ethics and Knowledge: Socrates emphasized questioning established beliefs and pursuing self-knowledge through critical thinking and ethical reflection. These ideas continue to shape our understanding of morality, justice, and the search for truth.

- Universal Relevance: Though living in ancient Greece, his ideas on self-examination, individual responsibility, and critical thinking transcend geographical and historical boundaries. They remain relevant across cultures and disciplines, offering valuable insights into the human condition and our pursuit of understanding.

Overall, Socrates’ legacy lies not just in specific philosophical doctrines but in his emphasis on critical inquiry, self-reflection, and the importance of questioning everything we think we know. His ideas continue to inspire individuals seeking a deeper understanding of themselves and the world, solidifying his position as a pivotal figure in shaping Western intellectual thought.

Plato and Courage

Setting: A quiet garden outside Athens. Socrates and his student, Plato, are engaged in a lively discussion.

Socrates: Tell me, Plato, what is courage? Is it the absence of fear, the ability to stand tall in the face of danger?

Plato: (Nodding thoughtfully) I believe so, Socrates. A courageous individual possesses unwavering bravery, unfazed by any threat.

Socrates: Hmm, an interesting thought. But consider this: a soldier, fearing the consequences of desertion, marches into battle without true conviction. Is this true courage?

Plato: (Frowning) Perhaps not. True courage may require more than just physical bravery. It might involve facing one’s fears and acting according to one’s principles, even if it means defying societal pressures.

Socrates: Indeed. Now, imagine a man who speaks out against injustice, knowing his words might anger those in power. While his heart might pound with fear, he chooses to act on what he believes to be right. Would you consider him courageous?

Plato: Absolutely! He possesses the courage of his convictions, prioritizing truth and justice even at personal risk.

Socrates: Now, we see that courage encompasses more than simply the absence of fear. It demands a deeper strength and willingness to act according to our values, even when faced with uncertainty or personal danger.

Plato: Your words are insightful, Socrates. True courage, then, requires physical bravery and the moral fortitude to do what is right, regardless of the consequences.

Socrates: However, Plato, remember that courage is not like recklessness. A truly courageous individual possesses the wisdom to discern real threats, assess risks, and act with prudence.

Plato: Of course, Socrates. True courage is a harmonious blend of bravery, wisdom, and moral conviction.

Socrates: And so, dear Plato, our quest for knowledge continues. Through dialogue and reflection, we strive to understand the complexities of courage and other profound concepts that shape the human experience.

(The afternoon sun casts long shadows as Socrates and Plato continue their conversation, their voices echoing through the peaceful garden.)

Xenophon and Good Leader

Setting: A quiet clearing just outside Athens. Socrates and his student, Xenophon, sit beneath a shade tree, enjoying the gentle breeze.

Socrates: Xenophon, what is it like to be a good leader?

Xenophon: (Ponders the question) I believe a good leader is someone who commands respect and obedience, someone strong and decisive. They know what must be done and ensure it is carried out efficiently.

Socrates: Interesting perspective. But consider a general who leads his soldiers into a battle they have no chance of winning simply because he craves victory. Is he still a good leader?

Xenophon: (Frowning) No, of course not. A true leader wouldn’t sacrifice the lives of their followers for their gain.

Socrates: Indeed. True leadership is not merely about issuing commands and expecting obedience. It requires wisdom, judgment, and a deep understanding of followers. A good leader inspires and motivates others to achieve a common goal, considering their well-being and fostering a shared purpose.

Xenophon: I see your point, Socrates. Perhaps true leadership involves balancing strength and compassion, ensuring efficiency while considering the needs of those they lead.

Socrates: Perhaps. Now, imagine a wealthy landowner who simply gives away his wealth without providing his workers with the tools or skills they need to earn their living. Is that true leadership?

Xenophon: (Shakes his head) No, that wouldn’t be helpful in the long run. A good leader empowers those they lead, providing opportunities for growth and self-sufficiency.

Socrates: Indeed. True leadership is not simply about showering others with wealth or authority. It involves guiding and empowering them, fostering their potential, and enabling them to contribute their unique skills to the collective good.

Xenophon: Your words offer valuable insight, Socrates. So, a good leader is not just strong but wise, compassionate, and empowering.

Socrates: It seems so, Xenophon. Just as we continually strive to learn and grow, true leadership is a journey of constant self-reflection and improvement, seeking to understand and inspire those we lead on the path toward a shared purpose.

(The afternoon sun casts long shadows as Socrates and Xenophon continue their conversation, their voices echoing through the peaceful clearing.)

Aristophanes and Love

Setting: A bustling Athenian symposium filled with music, laughter, and conversation. Renowned for his provocative questions, Socrates sits amongst a young man discussing love.

Aristophanes: (Exuberantly) Love! It’s a pursuit of wholeness! We were once whole beings, split in two by the gods, and now we spend our lives searching for our missing half!

Socrates: (Intrigued) A fascinating notion, Aristophanes. But surely love extends beyond this physical longing.

Agathon: (Raising his cup) I agree, Socrates. Love is about beauty! We are drawn to physical and spiritual beauty and seek to possess or be near it.

Socrates: (Nodding) But beauty is subjective, wouldn’t you agree? One man may find what another deems plain. Can something so fleeting truly be the essence of love?

**(A young man named Phaedrus leans forward, captivated by the conversation)

Phaedrus: Perhaps love isn’t about getting something but giving. It’s about inspiring us to become better versions of ourselves to reach for something higher.

Socrates: (Smiling) An interesting thought, Phaedrus. But who defines “better”? And does love require the sacrifice of one’s individuality for the sake of another?

**(A thoughtful silence falls over the group)

Socrates: Perhaps, my friends, love is not a single entity but a multifaceted experience. It can encompass physical attraction, intellectual stimulation, shared values, and a desire for growth.

Aristophanes: (Raises his eyebrows) Intriguing. So, love is a complex dance of different elements?

Socrates: Indeed. And like any dance, it requires understanding, respect, and a willingness to learn from each other.

Agathon: By your account, Socrates, love becomes a continuous journey of exploration, not just a destination.

Socrates: Perhaps. Through this exploration, through open communication and shared experiences, we truly connect and grow together in love.

**(The symposium resumes lively chatter, but the young men carry Socrates’ words with them, forever questioning and seeking a deeper understanding of love’s complex nature.)

Elara and Wisdom

Setting: A bustling marketplace in ancient Athens. Socrates, an elderly man with a twinkle in his eye, approaches a young woman named Elara, known for her curiosity and desire for knowledge.

Socrates: Greetings, Elara. Are you enjoying the vibrant energy of the marketplace today?

Elara: Indeed, Socrates. It’s a constant source of fascination, observing the diverse people and the stories they carry. But sometimes, I find myself overwhelmed by the complexities of life and wonder if true wisdom can ever be attained.

Socrates: (Nods thoughtfully) A valid question that many grapple with. But perhaps it’s not about having all the answers, Elara, but rather about the journey of seeking them.

Elara: (Raises an eyebrow) What do you mean?

Socrates: Imagine wisdom as a mountain peak shrouded in mist. We, as individuals, embark on a lifelong trek, navigating treacherous paths, learning from our missteps, and striving to reach the summit. Though the journey is challenging, the ascent itself holds immense value.

Elara: The pursuit itself being valuable? Interesting. But surely, there must be some ultimate knowledge waiting at the peak, a grand revelation that justifies the effort.

Socrates: Perhaps. But consider this, Elara. As we climb, the world around us unfolds, presenting new perspectives and challenging previous assumptions. The very act of seeking, of questioning, and engaging with diverse viewpoints cultivates wisdom in itself.

Elara: So, true wisdom lies in the destination and the journey itself? In the continuous pursuit of knowledge and understanding?

Socrates: Indeed. Each question you ask, each conversation you engage in, and each experience you encounter contributes to your tapestry of knowledge. And this tapestry allows you to navigate the complexities of life with greater clarity and purpose.

Elara: Your words offer a different perspective, Socrates. Realizing that pursuing wisdom is a constant journey open to continuous learning and growth is empowering.

Socrates: Remember, Elara, true wisdom is not passive but active engagement with the world around you. We truly find the seeds of knowledge and understanding through constant questioning, exploration, and reflection.

(The marketplace buzz continues around them as Elara reflects on Socrates’ words, her face filled with a glimmer of determination and a renewed sense of purpose in her ongoing quest for wisdom.)

Alcibiables and Greatness

Here’s a brief fictional dialogue between Socrates and Alcibiades, exploring themes of self-knowledge and ambition.

Setting: Ancient Athens, a public square.

Characters:

- Socrates: A renowned Athenian philosopher known for his probing questions and humble demeanor.

- Alcibiades: A young, ambitious Athenian aristocrat admired for his beauty and political aspirations.

(Alcibiades walks through the square, surrounded by admirers.)

Socrates: (Approaches Alcibiades calmly) Alcibiades, son of Cleinias, you seem to be the center of much attention today.

Alcibiades: (Smiling) Greetings, Socrates. As you can see, the people of Athens recognize my potential.

Socrates: Indeed, your potential is undeniable. Everyone speaks of your charm, your intellect, and your leadership qualities.

Alcibiades: (Proudly) And rightly so. I am destined for greatness!

Socrates: Perhaps. But have you ever considered, Alcibiades, what truly defines greatness?

Alcibiades: (Slightly taken aback) Greatness? I strive to be a leader, a man of power and influence.

Socrates: And what would you do with that power? To gain wealth? To conquer enemies? To win the admiration of the crowd?

Alcibiades: Well, those things are not to be dismissed.

Socrates: Certainly not. But consider this: True greatness lies not in external things but in understanding oneself.

Alcibiades: How does understanding oneself lead to greatness?

Socrates: By knowing yourself, your strengths and weaknesses, your motivations and desires, you can act with purpose and wisdom. A leader who understands themselves can lead others effectively and ethically.

Alcibiades: (Contemplative) You challenge me, Socrates. Perhaps I have been too focused on outward appearances and not enough on what lies within.

Socrates: It is a worthy journey, Alcibiades. To truly understand yourself, one must constantly question, “Who am I?” and “What is my true purpose?”

Alcibiades: I appreciate your wisdom, Socrates. I will consider your words carefully.

(The two men part ways, Alcibiades with a thoughtful expression on his face.)

Points to remember:

- This is a fictionalized representation based on the themes and style of Socratic dialogues.

- The actual dialogues might have different specific details and arguments.

- The point illustrates how Socrates used questioning and critical thinking to stimulate self-reflection and the pursuit of knowledge.

This brief exchange demonstrates how, although their historical authenticity might be debated, the dialogues between Socrates and Alcibiades offer thought-provoking insights into the importance of self-knowledge and ethical leadership.

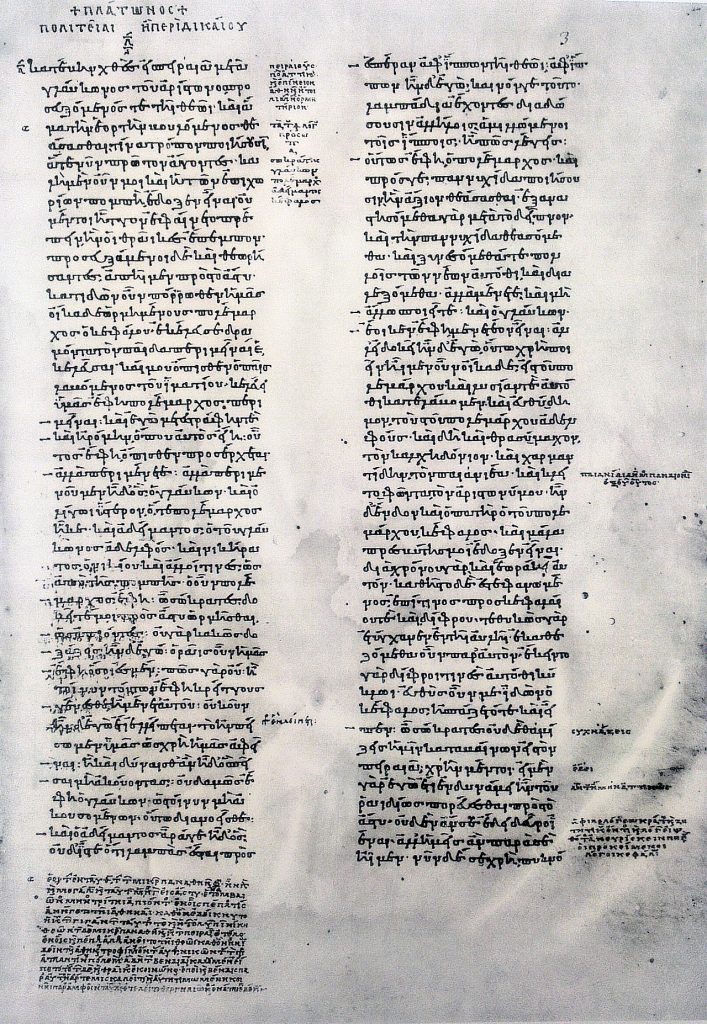

Republic

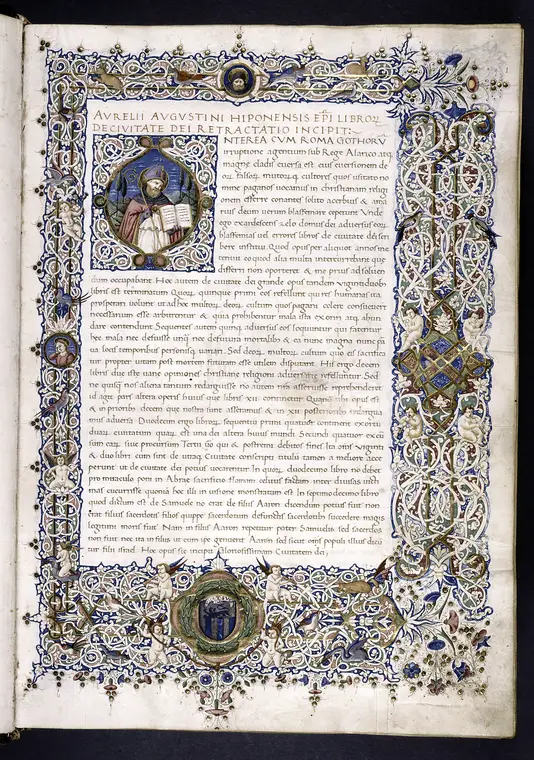

The title page of the oldest complete manuscript is Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Gr. 1807 (late 9th century) (Wiki Image).

Socrates (c. 470-399 BCE) was a central figure in ancient Greek philosophy and the main character in Plato’s philosophical dialogues, including his most famous work, “The Republic.” Here’s a breakdown of the connection between Socrates, “The Republic,” and its place in history:

Socrates, the Philosopher: