Colosseum, Pantheon, and Hagia Sophia: Roman Engineering and Architecture

The Colosseum, Pantheon, and Hagia Sophia are three monumental structures that exemplify the ingenuity and grandeur of Roman engineering and architecture. Each reflects the cultural and technological advancements of its respective eras.

Colosseum (70-80 AD): A Testament to Roman Engineering Prowess

- Purpose: The Colosseum, also known as the Flavian Amphitheatre, was designed as a grand entertainment venue for the Roman people. It hosted gladiatorial combats, animal hunts, mock sea battles, and other public spectacles.

- Engineering Feats: The Colosseum is a marvel of Roman engineering. Its elliptical shape accommodated up to 80,000 spectators. Its intricate network of arches, vaults, and tunnels facilitated the efficient movement of crowds, gladiators, and animals. The velarium, a retractable awning system, provided shade and protection from the elements.

- Architectural Style: The Colosseum’s exterior showcases the classic elements of Roman architecture, including Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian columns. Its interior is adorned with statues and reliefs. The Colosseum’s design prioritizes functionality, durability, and visual impact.

Pantheon (126 AD): A Tribute to Roman Innovation and Precision

- Purpose: The Pantheon was initially dedicated to all the gods of Rome. It later became a Christian church.

- Engineering Marvel: The Pantheon’s most notable feature is its massive dome, the largest unreinforced concrete dome ever built. The oculus, a circular opening at the top of the dome, allows natural light to illuminate the interior, creating a breathtaking effect.

- Architectural Style: The Pantheon’s design combines Greek and Roman architectural elements. The portico, with its Corinthian columns and pediment, resembles Greek temples, while the dome and its coffering represent Roman engineering and aesthetic sensibilities.

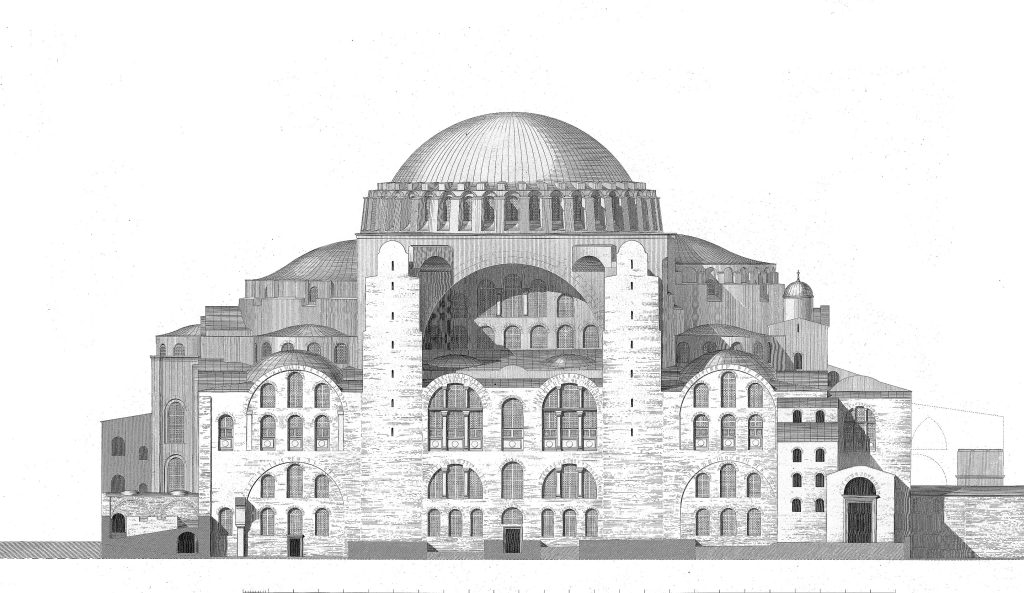

Hagia Sophia (537 AD): A Fusion of Roman and Byzantine Splendor

- Purpose: Originally built as a cathedral during the Byzantine Empire, Hagia Sophia later served as a mosque and is now a museum.

- Engineering Innovation: While not strictly Roman in origin, the Hagia Sophia builds upon Roman engineering principles. Its massive dome, supported by pendentives, showcases an innovative approach to dome construction. Using buttresses and half-domes further stabilizes the structure and creates a sense of spaciousness.

- Architectural Style: Hagia Sophia represents a fusion of Roman and Byzantine architectural styles. The exterior is characterized by its massive brickwork and towering minarets (added later), while the interior is adorned with intricate mosaics, marble columns, and ornate decorations.

Comparative Analysis:

- Colosseum: Demonstrates the Roman mastery of large-scale engineering for public entertainment.

- Pantheon: Showcases Roman innovation in concrete construction and dome design.

- Hagia Sophia: Illustrates the evolution of Roman engineering principles into the Byzantine era, incorporating new architectural elements and artistic styles.

These three magnificent structures are enduring testaments to their builders’ ingenuity, ambition, and artistic vision. They continue to inspire awe and wonder, reminding us of the enduring legacy of Roman engineering and its profound influence on the architectural world.

Colosseum History

The exterior of the Colosseum shows a partially intact outer wall (left) and a primarily intact inner wall (center and right) (Wiki Image).

While there aren’t direct quotes from individuals about the Colosseum from ancient times, here are ten quotes that capture its essence, significance, and enduring legacy:

- “While stands the Colosseum, Rome shall stand; when falls the Colosseum, Rome shall fall; and when Rome falls, the world.” – Venerable Bede (often attributed to him)

- “A ruin – yet what a ruin!” – Lord Byron

- “The gladiators died for the emperor; the martyrs died for God.” – Tertullian

- “The Colosseum is a testament to the grandeur of Rome, a reminder of its power and ambition.” – Unknown

- “The Colosseum is a monument not only to the brutality of the Roman Empire but also to its ingenuity and engineering prowess.” – Unknown

- “The Colosseum is a place where history comes alive, where the echoes of the past still resonate within its walls.” – Unknown

- “The Colosseum is a reminder of the fleeting nature of human power and the enduring legacy of human creativity.” – Unknown

- “The Colosseum is a silent witness to the triumphs and tragedies of the Roman Empire.” – Unknown

- “The Colosseum is a place of contrasts, where beauty and brutality coexisted in the heart of ancient Rome.” – Unknown

- “The Colosseum stands as a timeless symbol of Rome’s eternal glory and its enduring impact on Western civilization.” – Unknown

| Year | Event/Development |

|---|---|

| 64 AD | The Great Fire of Rome destroyed much of the city, including the area where the Colosseum was to be built. |

| 69 AD | Vespasian becomes Emperor, beginning the Flavian dynasty. He decides to build a grand amphitheater on the site of Nero’s former palace and artificial lake. |

| 70-72 AD | Construction of the Colosseum begins. Tens of thousands of slaves and prisoners of war are used as laborers. |

| 80 AD | Emperor Titus officially inaugurated the Colosseum. The opening celebrations lasted 100 days and included gladiatorial combats, animal hunts, and mock naval battles. |

| 81 AD | Domitian, Titus’s brother, became Emperor. He added the hypogeum (an underground network of tunnels and chambers) to the Colosseum. |

| 2nd – 3rd Centuries AD | – The Colosseum is at its peak, hosting regular games and spectacles. <br> – Gladiatorial contests, animal hunts, public executions, and even mock naval battles (naumachiae) are held. <br> – Modifications and repairs are made to the structure. |

| 217 AD | A major fire damages the upper levels of the Colosseum. |

| 248 AD | Games are held to celebrate the 1,000th anniversary of the founding of Rome. |

| 4th Century AD | – The popularity of gladiatorial combat declines due to the influence of Christianity. <br> – Animal hunts continue to be held. |

| 404 AD | The last gladiatorial combat is held in the Colosseum. |

| 5th Century AD | – The Western Roman Empire collapses. <br> – The Colosseum falls into disrepair and is used as a source of building materials. |

| 6th – 12th Centuries | – The Colosseum is used for various purposes, including housing, workshops, and a Christian shrine. <br> – The Frangipane family fortifies the Colosseum and uses it as a fortress. |

| 1349 AD | A major earthquake causes significant damage to the Colosseum. |

| 14th – 18th Centuries | – The Colosseum is used as a quarry for building materials. <br> – Stone is taken to construct palaces, churches, and other structures in Rome. |

| 18th Century | – Pope Benedict XIV consecrated the Colosseum as a sacred site in memory of the Christian martyrs believed to have died there. <br> – Efforts to preserve and restore the Colosseum begin. |

| 19th – 20th Centuries | – Archaeological excavations and restoration projects are undertaken. <br> – The Colosseum becomes a major tourist attraction. |

| 21st Century | – Ongoing restoration and conservation efforts continue. <br> – The Colosseum remains one of the most iconic symbols of ancient Rome and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. |

The Colosseum, the Flavian Amphitheatre, is an enduring symbol of ancient Rome and its rich history. Located in the heart of Rome, this massive amphitheater was a marvel of engineering and a testament to the grandeur of the Roman Empire.

Construction and Inauguration:

- Construction Begins: Construction of the Colosseum began under Emperor Vespasian around 70-72 AD. It was built on the grounds of what was once Nero’s Golden House, a lavish palace complex.

- Completion and Inauguration: The Colosseum was officially inaugurated in 80 AD by Emperor Titus, Vespasian’s son, with a series of 100-day games that included gladiatorial combats, animal hunts, and mock sea battles.

- Modifications and Additions: The amphitheater underwent further changes and additions during Emperor Domitian’s reign (81-96 AD).

Architecture and Design:

- Elliptical Shape: The Colosseum is an elliptical amphitheater, measuring approximately 189 meters long and 156 meters wide.

- Capacity: Depending on the seating configuration, it could accommodate an estimated 50,000 to 80,000 spectators.

- Seating: The seating was arranged in tiers, with the best seats reserved for the emperor, senators, and other dignitaries.

- Underground Chambers: The Colosseum featured a complex network of underground chambers and tunnels known as the hypogeum. These chambers housed animals, gladiators, and stage props and contained elaborate mechanisms for raising and lowering them into the arena.

- Velarium: The Colosseum was equipped with a retractable awning system called the velarium, which provided shade for the spectators.

Uses and Games:

- Gladiatorial Contests: Gladiatorial combats were the most popular events held in the Colosseum. Gladiators, who were often slaves or prisoners of war, fought each other or wild animals to the death.

- Animal Hunts (Venationes): Exotic animals from across the empire were brought to the Colosseum for spectacular hunts.

- Mock Sea Battles (Naumachiae): The arena could be flooded to stage elaborate mock sea battles.

- Public Executions: The Colosseum was also used for public executions of criminals and prisoners.

Decline and Reuse:

- Decline: After the fall of the Roman Empire, the Colosseum fell into disuse and neglect.

- Medieval Period: During the Middle Ages, it was used as a fortress, a quarry for building materials, and even a Christian shrine.

Modern Times:

- Restoration and Preservation: In the 18th century, efforts began to preserve and restore the Colosseum. It is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of Rome’s most popular tourist attractions.

- Symbol of Rome: The Colosseum remains an iconic symbol of Rome and its rich history. It is a reminder of the power and grandeur of the Roman Empire, as well as the brutal realities of its entertainment and social practices.

This overview of the Colosseum’s history is helpful! Let me know if you have any other questions.

Colosseum YouTube Video

- The Brutal History of the Roman Colosseum by Beyond Facts

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7qype7X0zJ8

- Views: 612,990

- Rome, Italy: The Colosseum – Rick Steves’ Europe Travel Guide – Travel Bite by Rick Steves’ Europe

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xaSbYIeqGWg

- Views: 924,856

- Secrets of the Colosseum (Full Episode) | Lost Treasures of Rome | National Geographic by National Geographic

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=evmyQGmuzqA

- Views: 1,316,579

- The Colosseum, Rome by Simple History

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U6oPfmJcU8s

- Views: 1,064,991

- The Hidden Engineering of the Colosseum by Deconstructed

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bmvxRMYxlhE

- Views: 2,594,966

Construction of the Colosseum began under the reign of Emperor Vespasian around 70-72 AD. It was built on the grounds of what was once Nero’s Golden House, a lavish palace complex. The Colosseum was officially inaugurated in 80 AD by Emperor Titus, Vespasian’s son, with a series of 100-day games that included gladiatorial combats, animal hunts, and mock sea battles. The amphitheater underwent further changes and additions during Emperor Domitian’s reign (81-96 AD).

The Colosseum, the Flavian Amphitheatre, is an iconic symbol of ancient Rome and a testament to its architectural and engineering prowess.

Construction of this magnificent amphitheater began under the reign of Emperor Vespasian in around 70-72 AD, following the destruction of Rome in the Great Fire of 64 AD. It was built on the grounds of what was once Nero’s Golden House, a sprawling and opulent palace complex that had fallen into disrepair.

The Colosseum was officially inaugurated in 80 AD by Emperor Titus, Vespasian’s son, with a 100-day grand opening ceremony. During this time, the amphitheater hosted a variety of spectacles, including gladiatorial combats, animal hunts, and even mock sea battles.

The Colosseum could hold an estimated 50,000 to 80,000 spectators, making it the largest amphitheater ever built in the Roman Empire. Its innovative design featured a complex system of tunnels and chambers beneath the arena floor, known as the hypogeum, which housed gladiators, animals, and stage machinery.

The amphitheater underwent further changes and additions during the reign of Emperor Domitian (81-96 AD), including the addition of a fourth level and the installation of a retractable awning to protect spectators from the sun and rain.

Today, the Colosseum stands as a testament to the grandeur and brutality of ancient Rome, attracting millions of visitors each year who come to marvel at its architectural splendor and imagine the thrilling spectacles that once took place within its walls.

Elliptical Shape: The Colosseum is an elliptical amphitheater, measuring approximately 189 meters long and 156 meters wide. Capacity: It could accommodate an estimated 50,000 to 80,000 spectators, depending on the seating configuration.

The Colosseum, an architectural marvel of ancient Rome, is renowned for its elliptical shape and impressive capacity.

Elliptical Shape:

The Colosseum’s elliptical design, measuring approximately 189 meters long and 156 meters wide, is a testament to Roman engineering ingenuity. This shape served several purposes:

- Optimal Viewing: The elliptical form ensured that spectators from all sections had a clear view of the arena, enhancing their overall experience.

- Acoustics: The shape also contributed to excellent acoustics, allowing the sounds of the games to reverberate throughout the amphitheater.

- Structural Integrity: The elliptical design evenly distributed the structure’s weight, contributing to its stability and longevity.

Capacity:

The Colosseum was a colossal structure with a seating capacity that varied depending on the configuration. It is estimated to have held between 50,000 and 80,000 spectators. This immense capacity allowed for grand spectacles and events that captivated the Roman populace.

The combination of its elliptical shape and vast capacity made the Colosseum a truly remarkable feat of engineering and a symbol of Roman power and entertainment.

Seating: The seating was arranged in tiers, with the best seats reserved for the emperor, senators, and other dignitaries.

The Colosseum’s seating arrangement reflected the hierarchical structure of Roman society,

with the best seats reserved for the most important figures.

The seating was divided into several tiers:

-

Ima Cavea (First Tier): This was the most prestigious section, reserved for the emperor, senators, Vestal Virgins, and other high-ranking officials. It offered the best views of the arena and was often adorned with luxurious decorations.

-

Media Cavea (Middle Tier): This section was occupied by the equestrian class, wealthy Roman citizens who could afford more expensive tickets.

-

Summa Cavea (Upper Tier): The upper tier was designated for ordinary Roman citizens, with wooden benches providing basic seating.

-

Maenianum Summum in Ligneis (Top Tier): This section was added later during Emperor Domitian’s reign and was primarily for women and the lower classes. It offered standing room only and had limited visibility of the arena.

This hierarchical seating arrangement not only reinforced social distinctions but also ensured that the most important members of Roman society had the best views of the spectacles held within the Colosseum.

Underground Chambers: The Colosseum featured a complex network of underground chambers and tunnels known as the hypogeum. These chambers housed animals, gladiators, and stage props and contained elaborate mechanisms for raising and lowering them into the arena.

Beneath the Colosseum’s arena floor lay a labyrinthine network of underground chambers and tunnels known as the hypogeum. This hidden world played a crucial role in the spectacles that unfolded above.

The hypogeum served multiple purposes:

-

Animal Housing: The chambers housed various wild animals, including lions, tigers, bears, and elephants, used in animal hunts and gladiatorial combats.

Colosseum animal housing -

Gladiator Preparation: Gladiators prepared for battle in the hypogeum, practicing their skills and awaiting their turn in the arena.

Colosseum gladiator preparation -

Storage: The tunnels storstorege props, scenery, and equipment used in the ous performances.

-

Mechanical Systems: The hypogeum contained complex systems of elevators and trapdoors powered by slaves and animals that raised and lowered animals, gladiators, and props into the arena. These mechanisms added an element of surprise and spectacle to the events.

Colosseum mechanical systems

The hypogeum was a technological marvel of its time, showcasing Roman engineering ingenuity and their dedication to creating awe-inspiring spectacles. Today, visitors to the Colosseum can explore portions of the hypogeum, gaining a deeper understanding of the complex operations beneath the arena and the immense scale of Roman entertainment.

Velarium: The Colosseum was equipped with a retractable awning system called the velarium, which provided shade for the spectators.

The Colosseum’s velarium was an engineering marvel of its time, providing much-needed relief from the scorching Roman sun for spectators.

The velarium was a massive canvas or linen awning system supported by a complex network of ropes and pulleys. It was operated by a team of sailors from the Roman navy, who used their expertise in rigging and sails to manipulate the awning.

The velarium could cover a significant portion of the amphitheater, offering shade to up to one-third of the arena and the seating area. This not only provided comfort for the spectators but also helped to regulate the temperature within the Colosseum.

The velarium was also believed to have created a ventilation updraft, drawing cooler air into the amphitheater and making the environment more pleasant for the audience.

The intricate design and operation of the velarium highlight the Romans’ ingenuity and dedication to providing a comfortable and enjoyable experience for the spectators who attended the events at the Colosseum.

Gladiatorial Contests: Gladiatorial combats were the most popular events held in the Colosseum. Gladiators, who were often slaves or prisoners of war, fought each other or wild animals to the death.

Gladiatorial combats were the main attraction at the Colosseum, drawing massive crowds eager to witness the thrilling and often brutal spectacles.

Gladiators were typically slaves, prisoners of war, or condemned criminals who were trained in various combat styles and equipped with different weapons and armor. They fought each other or wild animals in a fight to the death, often for the audience’s amusement.

Gladiators were categorized into different classes based on their fighting style, weapons, and armor. Some of the most common types included:

- Murmillo: Heavily armored gladiators with a large shield and sword.

- Retiarius: Lightly armored gladiators who fought with a net and trident.

- Secutor: Gladiators who specialized in fighting the retiarius.

- Thraex: Gladiators armed with a small shield and curved sword.

The gladiatorial combats were not random fights; they were often choreographed and followed specific rules and regulations. However, the risk of death was genuine, and gladiators could face severe injury or death in the arena.

Despite the brutality of the gladiatorial combats, they were incredibly popular among the Roman populace. The gladiators were seen as heroes and celebrities, and their fights were a source of entertainment and excitement for the masses.

Animal Hunts (Venationes): Exotic animals from across the empire were brought to the Colosseum for spectacular hunts.

Animal hunts, known as venationes in Latin, were another popular form of entertainment at the Colosseum. Exotic animals from all corners of the Roman Empire were brought to Rome for these extravagant displays.

The venationes featured a variety of animals, including:

-

Large Predators: Lions, tigers, bears, leopards, and other big cats were crowd favorites, often pitted against gladiators or other animals in thrilling contests.

-

Herbivores: Elephants, rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses, and giraffes were showcased for their exotic nature and sheer size, sometimes used in elaborate displays or hunts.

-

Other Animals: Ostriches, crocodiles, bulls, and even exotic birds were also featured in the venationes, adding to the spectacle and variety of the events.

The animal hunts were about killing animals and demonstrating Roman power and dominance over the natural world. The ability to capture and transport exotic animals from distant lands was a testament to the vast reach and resources of the Roman Empire.

The venationes were often accompanied by elaborate scenery and props, creating immersive environments that transported the audience to faraway lands. These events were a source of fascination and wonder for the Roman populace, offering a glimpse of the exotic and dangerous creatures that inhabited the edges of their empire.

Mock Sea Battles (Naumachiae): The arena could be flooded to stage elaborate mock sea battles.

The Colosseum’s versatility extended beyond gladiatorial combats and animal hunts. It could also be transformed into a massive artificial lake to host spectacular mock sea battles known as naumachiae.

These elaborate events involved flooding the arena floor to create a temporary body of water, where miniature warships, crewed by condemned criminals or prisoners of war, engaged in simulated naval battles.

The naumachiae were grand spectacles that required significant engineering feats and logistical planning. Water was channeled into the Colosseum from nearby aqueducts or the Tiber River, and a system of drainage tunnels was used to empty the arena afterward.

The mock sea battles were visually impressive and strategically complex, with ships maneuvering and engaging in combat tactics. The events were often accompanied by elaborate scenery and props, creating immersive environments that transported the audience to the high seas.

While historians debate the frequency and scale of the naumachiae at the Colosseum, the evidence suggests that these events were rare and costly undertakings reserved for special occasions and celebrations.

The naumachiae highlight the Romans’ ingenuity and desire to push entertainment boundaries. These extraordinary events were a testament to Roman engineering prowess and their ability to create awe-inspiring spectacles that captivated the masses.

Public Executions: The Colosseum was also used for public executions of criminals and prisoners.

In addition to gladiatorial combats, animal hunts, and mock sea battles, the Colosseum was also a site of public executions. These grim events were often part of the broader spectacles held within the amphitheater and served as entertainment and social control.

Various methods of execution were employed at the Colosseum, including:

-

Damnatio ad bestias: Condemned criminals were thrown to wild animals, such as lions or bears, to be mauled to death. This form of execution was particularly gruesome and served as a deterrent to crime.

-

Burning at the Stake: Criminals were sometimes tied to stakes and burned alive in the arena. This form of execution was often reserved for those accused of particularly heinous crimes.

-

Crucifixion: This method of execution involved nailing the condemned to a cross, where they would slowly die from exposure and dehydration. Crucifixion was a common form of capital punishment in the Roman Empire and was sometimes carried out in the Colosseum.

Public executions served several purposes:

- Punishment: They were a form of punishment for criminals and a deterrent to potential offenders.

- Entertainment: The gruesome nature of these events provided a spectacle for the audience, satisfying their thirst for violence and excitement.

- Social Control: Public executions reinforced the power of the Roman state and served as a warning to those who might challenge its authority.

While public executions were a common practice in ancient Rome, the extent to which they occurred at the Colosseum is debated by historians. Some scholars believe that executions were relatively rare, while others argue that they were a regular part of the amphitheater’s program.

Regardless of their frequency, public executions at the Colosseum represent a dark chapter in Roman history, highlighting the brutality and violence that were often associated with the spectacles held within its walls.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the Colosseum fell into disuse and neglect. During the Middle Ages, it was used as a fortress, a quarry for building materials, and even a Christian shrine. In the 18th century, efforts began to preserve and restore the Colosseum.

Following the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century AD, the Colosseum gradually fell into disuse and disrepair. The grand spectacles that once captivated the Roman populace ceased,

and the amphitheater was left to the elements.

During the Middle Ages, the Colosseum was repurposed for various uses:

-

Fortress: Powerful Roman families, such as the Frangipani and Annibaldi, fortified the Colosseum and used it as a stronghold during their power struggles.

-

Quarry: The Colosseum’s vast stores of travertine stone were plundered for building materials, contributing to its deterioration. Many of Rome’s churches and palaces were constructed using stones taken from the amphitheater.

-

Christian Shrine: In the 14th century, the Colosseum was dedicated as a Christian shrine, with chapels and altars erected within its walls. This transformation reflected the changing religious landscape of Europe and the Colosseum’s new role as a place of worship.

In the 18th century, a growing appreciation for classical antiquity led to renewed interest in the Colosseum. Pope Benedict XIV declared it a sacred site, and efforts began to preserve and restore what remained of the once-mighty amphitheater.

These early restoration efforts were limited and often haphazard, but they laid the groundwork for the more comprehensive conservation projects that followed in the 19th and 20th centuries. Today, the Colosseum stands as a testament to ancient Rome’s enduring legacy and the efforts of those who have worked to preserve its iconic structure for future generations.

It is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of Rome’s most popular tourist attractions. The Colosseum remains an iconic symbol of Rome and its rich history. It reminds visitors of the power and grandeur of the Roman Empire, as well as the brutal realities of its entertainment and social practices.

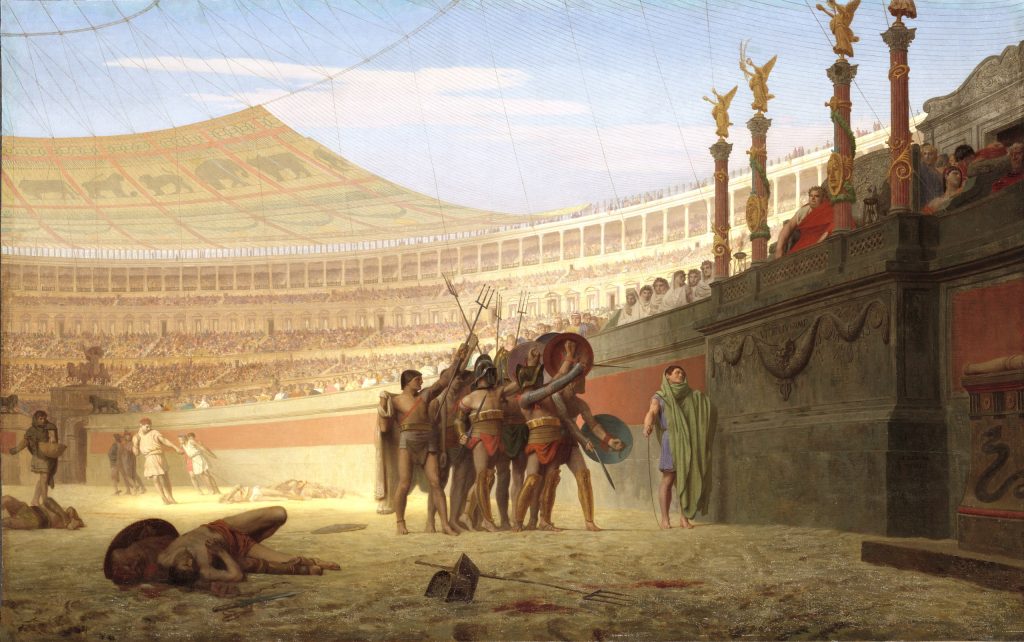

Ave Imperator, morituri te salutant (Hail, Cesar, those who will die to salute you), by Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1859 (Wiki Image).

Ave Imperator, morituri te salutant (Hail, Cesar, those who will die to salute you), by Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1859 (Wiki Image).

Absolutely! That’s a perfect summary of the Colosseum’s current status and its enduring legacy. Here’s the information combined with your previous input for a comprehensive overview:

The Colosseum: From Imperial Glory to Modern Icon

Construction, Inauguration, and Modifications:

- Construction Begins: Construction of the Colosseum began under the reign of Emperor Vespasian in around 70-72 AD. It was built on the grounds of what was once Nero’s Golden House, a lavish palace complex.

- Completion and Inauguration: The Colosseum was officially inaugurated in 80 AD by Emperor Titus, Vespasian’s son, with a series of 100-day games that included gladiatorial combats, animal hunts, and mock sea battles.

- Modifications and Additions: The amphitheater underwent further changes and additions during Emperor Domitian’s reign (81-96 AD).

Decline, Repurposing, and Preservation:

- Middle Ages: After the fall of the Roman Empire, the Colosseum fell into disuse and neglect. It was used as a fortress, a quarry for building materials, and even a Christian shrine.

- Renaissance and Beyond: In the 18th century, efforts began to preserve and restore the Colosseum. Today, it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognizing its outstanding universal value.

Modern Significance:

- Popular Tourist Attraction: The Colosseum is one of Rome’s most popular tourist attractions, drawing millions of visitors annually.

- Iconic Symbol: It remains an enduring symbol of Rome and its rich history, showcasing the grandeur and engineering prowess of the Roman Empire.

- Reminder of the Past: The Colosseum starkly reminds us of the brutal realities of Roman entertainment and social practices, prompting reflection on the darker aspects of human history.

The Colosseum stands as a testament to the enduring power of human ingenuity and creativity, even amidst the complexities of history. Its legacy continues to captivate and inspire, offering valuable insights into the past while remaining a vibrant part of the present.

Pantheon History

Facade of the Pantheon, with the Pantheon obelisk (Wiki Image).

The Pantheon, as a building, doesn’t have quotes attributed to it. However, there are many quotes by famous individuals inspired by the Pantheon’s beauty, history, and architectural significance:

- Michelangelo: “It looks more like the work of angels than of men.” (Expressing his awe at the Pantheon’s grandeur and design)

- Thomas Jefferson: “The Pantheon…simple, erect, severe, austere, sublime.” (Appreciating the Pantheon’s simplicity and elegance)

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: “Earth proudly wears the Pantheon as her noblest temple.” (Recognizing the Pantheon’s enduring impact and influence)

- Lord Byron: “Simple, erect, severe, austere, sublime – Shrine of all saints and temple of all gods, From Jove to Jesus – spared and blest by time.” (Reflecting on the Pantheon’s transformation from pagan temple to a Christian church)

- Nathaniel Hawthorne: “The world has nothing else like the Pantheon…It is the one great thing in Rome, that I shall never forget.” (Emphasizing the Pantheon’s unique and unforgettable character)

- Mark Twain: “The Pantheon is perfectly beautiful…no other building in Rome impressed me so much.” (Acknowledging the Pantheon’s enduring beauty and impact)

- Oscar Wilde: “It is the most sublime building in the world.” (Expressing his admiration for the Pantheon’s magnificence)

- Le Corbusier: “The Pantheon is one of the most beautiful architectural forms ever created.” (Recognizing the Pantheon’s architectural significance)

- Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: “The Pantheon is a masterpiece of Roman engineering and architectural genius.” (Highlighting the Pantheon’s technical and artistic achievements)

- Unknown: “The Pantheon is a testament to the enduring power of human creativity and the pursuit of beauty and perfection.” (Reflecting on the Pantheon’s legacy and its ability to inspire awe and wonder)

| Year | Event/Development |

|---|---|

| 27 BC | – First Pantheon completed: Marcus Agrippa, a close friend and son-in-law of Emperor Augustus, constructed the first Pantheon, a rectangular temple dedicated to all the gods. |

| 80 AD | – Fire destroys the first Pantheon: The original building is destroyed in a fire that swept through Rome. |

| 118-125 AD | – Hadrian rebuilds the Pantheon: Emperor Hadrian rebuilds the Pantheon in its current circular form with its iconic dome. <br> – He retains the inscription attributing the building to Agrippa, leading to centuries of confusion about its origins. |

| c. 126-128 AD | – The Pantheon is likely dedicated: While the exact date is uncertain, evidence suggests it was dedicated around this time, possibly under Hadrian’s predecessor, Trajan. |

| 2nd – 3rd Centuries AD | – The Pantheon flourishes: It is a prominent temple in Rome dedicated to worshipping all the gods. <br> – It survives various challenges, including fires and earthquakes. |

| 330 AD | – Constantine moved the capital to Constantinople: The Roman Empire’s capital shifted eastward, and Rome’s importance diminished. <br> – This likely marks the beginning of a gradual decline in the Pantheon’s use and maintenance. |

| 4th Century AD | – Decline of paganism: With the rise of Christianity, traditional Roman religion declines, and the Pantheon’s role as a pagan temple diminishes. |

| 609 AD | – The Pantheon becomes a church: The Byzantine Emperor Phocas granted the Pantheon to Pope Boniface IV, who consecrated it as a Christian church, Santa Maria ad Martyres (St. Mary and the Martyrs). <br> – This conversion likely saves the Pantheon from further decay and destruction. |

| 7th – 14th Centuries | – The Pantheon as a church: It continues to function and is gradually modified and decorated with Christian artwork and relics. <br> – It remains a significant religious and cultural center in Rome. |

| 1349 AD | – Earthquake damage: A major earthquake causes significant damage to the Pantheon, particularly the portico. |

| 14th – 18th Centuries | – The Pantheon as a quarry: The Pantheon is used as a source of building materials, with bronze and marble being stripped for other projects. <br> – Despite this, the core structure survives. |

| 18th Century | – Preservation efforts begin: Pope Benedict XIV consecrates the Pantheon as a sacred site in memory of Christian martyrs. <br> – Early efforts are made to preserve and restore the building. |

| 19th – 20th Centuries | – Restoration and study: Archaeological excavations and restoration projects are undertaken to understand and preserve the Pantheon better. <br> – It has become a major tourist attraction and a symbol of ancient Rome’s architectural genius. |

| 21st Century | – Ongoing conservation: The Pantheon remains an active church and a major tourist attraction. <br> – Ongoing restoration and conservation efforts aim to preserve its historical and architectural significance for future generations. |

The Pantheon, a true marvel of ancient Roman architecture, is a testament to engineering ingenuity and artistic vision. Its rich history spans two millennia, reflecting Rome’s cultural and religious shifts.

Origins and Construction:

- Agrippa’s Pantheon: The original Pantheon was built in 27 BC by Marcus Agrippa, Emperor Augustus’s close friend and son-in-law. This initial structure was likely a traditional rectangular temple, but fire destroyed it in 80 AD.

- Domitian’s Reconstruction: Emperor Domitian rebuilt the Pantheon, which was again destroyed by fire in 110 AD.

- Hadrian’s Pantheon: The current structure, a masterpiece of Roman engineering, was constructed under Emperor Hadrian between 118-128 AD. The architect remains unknown, but the building’s innovative design and grandeur have captivated visitors for centuries.

Architectural Features:

- Portico: The grand entrance has 16 massive granite Corinthian columns supporting a triangular pediment.

- Interior: The interior is a vast cylindrical space adorned with marble, statues, and niches, creating a harmonious blend of grandeur and simplicity.

- The Dome: The Pantheon’s most striking feature is its massive dome, the largest unreinforced concrete dome ever built. It spans 43.3 meters (142 ft) in diameter and features a central oculus (opening) that allows natural light to flood the interior.

- Oculus: The oculus is the only light source, creating a dramatic interplay of light and shadow within the space.

Transformation into a Church:

- Dedication to Christian Martyrs: In 609 AD, the Pantheon was consecrated as a Christian church dedicated to St. Mary and the Martyrs. This act of repurposing preserved the building from further destruction and allowed it to remain a place of worship for centuries.

- Renaissance Inspiration: The Pantheon’s design inspired many Renaissance architects, including Michelangelo and Raphael.

Legacy:

- Architectural Influence: The Pantheon has been a model for countless historical buildings, influencing architects across Europe and the Americas.

- Symbol of Rome: The Pantheon remains an iconic symbol of Rome, its resilience reflecting its enduring legacy.

- Tourist Attraction: Today, it is a popular tourist destination, attracting millions of visitors each year who marvel at its architectural brilliance and historical significance.

The Pantheon’s enduring allure lies in its remarkable architectural design, rich history, and transformation from a pagan temple to a Christian church. It stands as a testament to the ingenuity of Roman engineers, the artistry of its builders, and the enduring power of human creativity.

Pantheon YouTube Video

- Rome’s Pantheon: The Secrets of the World’s Largest Dome of Its Time I SLICE HISTORY by SLICE History

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YPumOC0P1Us

- Views: 21,205

- History Summarized: The Pantheon by Overly Sarcastic Productions

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bd68UWTCur8

- Views: 539,513

- The Roman Pantheon Explained by Manuel Bravo

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JW5-7qGPl6U

- Views: 1,036,250

- Rome, Italy: The Pantheon – Rick Steves’ Europe Travel Guide – Travel Bite by Rick Steves’ Europe

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ExwRrjE4kRQ

- Views: 195,900

- Pantheon of Rome. Mystery of ancient Roman architecture in 3D by Andres Jalak

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yn2XdZfx93w

- Views: 182,050

The original Pantheon was built in 27 BC by Marcus Agrippa, Emperor Augustus’s close friend and son-in-law. This initial structure was likely a traditional rectangular temple, but fire destroyed it in 80 AD. Emperor Domitian rebuilt the Pantheon, which was again destroyed by fire in 110 AD. The current structure, a masterpiece of Roman engineering, was constructed under Emperor Hadrian between 118 and 128 AD. The architect remains unknown, but the building’s innovative design and grandeur have captivated visitors for centuries.

The Pantheon, one of Rome’s most iconic and well-preserved ancient structures, has a fascinating history of destruction and rebirth.

-

Original Construction:

Pantheon original constructionThe first Pantheon was built in 27 BC by Marcus Agrippa, Emperor Augustus’s close friend and son-in-law. This initial structure was likely a traditional rectangular temple dedicated to all the gods (Pantheon means “Temple of all Gods” in Greek).

-

Fire and Rebuilding:

Pantheon fireUnfortunately, this original Pantheon was destroyed by a fire in 80 AD. Emperor Domitian rebuilt the structure, but it was once again ravaged by fire in 110 AD.

-

Hadrian’s Masterpiece:

Pantheon HadrianThe current Pantheon, which we marvel at today, was constructed under Emperor Hadrian between 118-128 AD. The architect remains unknown, but their genius is evident in the building’s innovative design and impressive engineering.

-

Architectural Significance:

Pantheon interiorThe Pantheon is renowned for its massive dome, the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world. The dome’s oculus, a circular opening at the top, allows natural light to flood the interior, creating a dramatic, awe-inspiring atmosphere. The Pantheon’s design has influenced countless architects throughout history and continues to inspire and wonder.

The Pantheon’s enduring legacy is a testament to the ingenuity and skill of Roman architects and engineers. Despite its challenges, this remarkable building has stood the test of time, serving as a place of worship, a burial site for Italian kings, and a beloved tourist attraction.

Portico: The grand entrance has 16 massive granite Corinthian columns supporting a triangular pediment.

The Pantheon’s portico is a grand entrance that sets the stage for the awe-inspiring interior.

It features:

-

16 Granite Columns: The portico is supported by 16 massive granite columns arranged in three rows. These monolithic columns, each weighing approximately 60 tons, were quarried in Egypt and transported to Rome, a testament to Roman engineering and logistics.

-

Corinthian Capitals: The columns are topped with ornate Corinthian capitals featuring intricate carvings of acanthus leaves and other decorative elements. These capitals add a touch of elegance and grandeur to the portico.

-

Triangular Pediment: The portico is crowned by a triangular pediment, a classic architectural element often adorned with sculptures or reliefs. While the original pediment’s decoration is lost to time, its imposing structure remains a striking feature of the Pantheon’s facade.

The portico’s design reflects the influence of Greek architecture, particularly the use of columns and pediments. However, the Romans adapted and expanded upon these elements, creating a unique and imposing entrance that befits the Pantheon’s status as a temple to all the gods.

The portico transitions between the bustling city streets and the serene interior of the Pantheon. Its grand scale and intricate details prepare visitors for the awe-inspiring experience that awaits them inside.

Interior: The interior is a vast cylindrical space adorned with marble, statues, and niches, creating a harmonious blend of grandeur and simplicity.

The Pantheon’s interior is a masterpiece of Roman architecture, harmoniously blending grandeur and simplicity.

The vast cylindrical space is a testament to the Romans’ engineering skill and ability to create awe-inspiring interiors.

Key features of the interior include:

-

Marble: The walls and floor are adorned with colorful marble, creating a rich and luxurious atmosphere. The marble is sourced from various regions of the Roman Empire, showcasing the vastness and diversity of its resources.

-

Niches: Seven large niches, alternating between rectangular and semi-circular, punctuate the walls of the Pantheon. These niches originally housed statues of Roman gods and emperors, adding to the temple’s religious and political significance.

-

Coffered Dome: The dome’s interior features a series of recessed panels, known as coffers, which reduce the dome’s weight and create an intricate pattern of light and shadow.

-

Geometric Floor Pattern: The floor is paved with a geometric pattern of colored marble, adding to the interior’s visual complexity and beauty.

The Pantheon’s interior is a testament to the Romans’ ability to create functional and aesthetically pleasing spaces. The harmonious blend of grandeur and simplicity, the interplay of light and shadow, and the use of rich materials create an atmosphere of awe and reverence. This space has inspired countless architects and artists throughout history and continues to captivate visitors to this day.

The Dome: The Pantheon’s most striking feature is its massive dome, the largest unreinforced concrete dome ever built. It spans 43.3 meters (142 ft) in diameter and features a central oculus (opening) that allows natural light to flood the interior.

The Pantheon’s dome is the largest unreinforced concrete dome ever built. It spans an impressive 43.3 meters (142 ft) in diameter.

The dome is a marvel of engineering and a symbol of Roman ingenuity and architectural prowess. Its design features:

-

Coffered Ceiling: The dome’s interior is adorned with recessed panels, known as coffers, which reduce the dome’s weight and enhance its acoustic properties.

Pantheon coffered ceiling -

Oculus: The central opening, or oculus, is 9 meters (30 ft) in diameter and serves as the interior’s sole natural light source. The sunlight streaming through the oculus creates a dramatic, ever-changing illumination throughout the day.

Pantheon oculus -

Graded Concrete: The dome is constructed with varying types of concrete, with lighter materials used towards the top to reduce the overall weight and stress on the structure.

Pantheon dome crosssection

The Pantheon’s dome is a testament to the Romans’ mastery of concrete construction and their ability to create awe-inspiring spaces that have stood the test of time.

Oculus: The oculus is the only light source, creating a dramatic interplay of light and shadow within the space.

Beam in the dome of the Pantheon (Wiki Image).

The oculus, a circular opening at the apex of the Pantheon’s dome, is a defining feature of this architectural masterpiece. Measuring 9 meters (30 feet) in diameter, it serves as the interior’s sole source of natural light.

The oculus creates a captivating interplay of light and shadow within the Pantheon. As the sun moves across the sky, the beam of light projected through the oculus shifts and dances across the walls and floor, illuminating different parts of the space at various times of the day. This dynamic lighting effect adds a sense of drama and wonder to the interior, enhancing its spiritual and aesthetic qualities.

The oculus also serves a practical purpose, providing ventilation and regulating the temperature within the Pantheon. The open design allows for air circulation, preventing heat and moisture buildup.

In addition to its functional and aesthetic roles, the oculus holds symbolic significance. Some interpretations suggest that it represents the eye of the gods, watching over the Pantheon and its visitors. Others see it as a connection between the earthly and divine realms, a portal through which celestial light enters the human world.

The oculus is a testament to the ingenuity of Roman architects and engineers, who created a structure that functioned as a temple and a breathtaking work of art. Its unique design and the mesmerizing play of light and shadow continue to captivate visitors today, making it one of ancient Rome’s most iconic and enduring landmarks.

Dedication to Christian Martyrs: In 609 AD, the Pantheon was consecrated as a Christian church dedicated to St. Mary and the Martyrs. This act of repurposing preserved the building from further destruction and allowed it to remain a place of worship for centuries.

In 609 AD, the Pantheon underwent a significant transformation when it was consecrated as a Christian church dedicated to St. Mary and the Martyrs. This decision by Pope Boniface IV marked a turning point in the history of the building, ensuring its preservation and continued use for centuries to come.

This repurposing involved:

-

-

Removal of Pagan Elements: The statues of Roman gods and emperors that once adorned the niches were removed, and pagan symbols were replaced with Christian imagery.

-

Dedication to Christian Martyrs: The Pantheon was rededicated to St. Mary and the Martyrs, commemorating the early Christians who had been persecuted and killed for their faith. The bones of many martyrs were brought from the catacombs and placed within the Pantheon, adding to their religious significance.

-

The consecration of the Pantheon as a Christian church had several significant consequences:

-

Preservation: By transforming the Pantheon into a place of Christian worship, the church spared it from the destruction and neglect that befell many other ancient Roman buildings. The church ensured the structure’s maintenance and upkeep, allowing it to survive through the centuries.

-

Continuity of Worship: The Pantheon served as a place of worship, albeit for a different faith. The Christian rituals and traditions within its walls helped create a new layer of history and meaning for the building.

-

Cultural Significance: The Pantheon’s transformation into a Christian church reflected the changing religious landscape of Europe and the growing influence of Christianity. It became a symbol of the triumph of Christianity over paganism and a testament to the enduring power of faith.

The Pantheon’s dedication to St. Mary and the Martyrs marked a pivotal moment in its history, ensuring its survival and continued relevance. Today, it stands as a unique monument that bridges the pagan and Christian worlds, a testament to the enduring power of architecture and the adaptability of sacred spaces.

Renaissance Inspiration: The Pantheon’s design inspired many Renaissance architects, including Michelangelo and Raphael.

The Pantheon’s innovative design and grandeur inspired many Renaissance architects, who sought to emulate its harmonious proportions and engineering feats.

Michelangelo: The great Renaissance artist and architect Michelangelo was deeply impressed by the Pantheon. He is said to have called it “the work of angels, not of men.” The Pantheon’s dome, in particular, influenced Michelangelo’s design for the St. Peter’s Basilica dome in Vatican City. While St. Peter’s dome is larger, it shares many similarities with the Pantheon’s dome in terms of its shape, coffering, and use of an oculus.

Raphael: The renowned Renaissance painter and architect Raphael also admired the Pantheon. He studied its proportions and details, incorporating elements of its design into his own architectural projects. Raphael’s tomb within the Pantheon is a testament to his admiration for the building.

The Pantheon’s influence extended beyond Michelangelo and Raphael, inspiring countless other Renaissance architects who sought to revive the classical ideals of harmony, proportion, and beauty. The building’s enduring legacy can be seen in the countless churches, palaces, and other structures built in its image throughout the Renaissance and beyond.

The Pantheon’s ability to inspire generations of architects is a testament to its timeless design and enduring power. It serves as a reminder of the importance of studying and learning from the past while also pushing the boundaries of innovation and creativity.

Architectural Influence: The Pantheon has been a model for countless historical buildings, influencing architects across Europe and the Americas.

The Pantheon’s architectural influence is undeniable and far-reaching. It has served as a model for countless historic buildings across the globe, inspiring architects with its innovative design and timeless beauty. Here are a few examples:

Europe:

-

Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore (Florence Cathedral), Italy: The dome of this iconic cathedral, designed by Filippo Brunelleschi, was heavily influenced by the Pantheon’s dome. Brunelleschi studied the Pantheon’s construction techniques and used similar principles to create his masterpiece.

-

Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, Italy: Designed by Francesco Borromini, this Baroque church features a dome and oculus inspired by the Pantheon. Borromini’s innovative interpretation of the Pantheon’s design showcases its architectural principles’ adaptability and enduring appeal.

Americas:

-

Thomas Jefferson’s Rotunda, University of Virginia, USA: Thomas Jefferson, a great admirer of Roman architecture, modeled the Rotunda at the University of Virginia after the Pantheon. The building features a similar dome, portico, and interior layout.

-

U.S. Capitol Building, USA: Thomas U. Walter designed the U.S. Capitol Building’s dome, which draws inspiration from the Pantheon’s dome. The coffered ceiling, oculus, and overall proportions reflect this influence.

-

Low Memorial Library, Columbia University, USA: This neoclassical library, designed by McKim, Mead & White, features a domed reading room inspired by the Pantheon. The rotunda’s grandeur and the interplay of light and shadow evoke the spirit of the Pantheon’s interior.

These are just a few examples of the Pantheon’s lasting architectural legacy. Its innovative design and engineering principles continue to inspire architects and engineers today, making it a timeless masterpiece that has shaped the built environment for centuries.

The Pantheon remains an iconic symbol of Rome, its resilience reflecting its enduring legacy. Today, it is a popular tourist destination, attracting millions of visitors each year who marvel at its architectural brilliance and historical significance.

The portico (Wiki Image).

The portico (Wiki Image).

The Pantheon has a modillion, and across the large granite Corinthian columns, in enormous letters, was the Latin inscription:

M. AGRIPPA L.F. COS TERTIUM FECIT

In English, this means: “Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, a three-time consul, made this.”

Absolutely! The Pantheon’s resilience and enduring legacy make it an iconic symbol of Rome and its remarkable history. Here’s how it continues to captivate and inspire:

A Symbol of Roman Ingenuity and Architectural Brilliance:

- Unmatched Dome: The Pantheon’s most notable feature, the massive dome, is a testament to Roman engineering prowess. It remains the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome, a marvel of design and construction that has stood the test of time.

- Harmony and Balance: The Pantheon’s harmonious proportions, elegant design, and innovative use of natural light create visitors’ awe and wonder. Its architecture embodies the classical ideals of beauty, order, and balance.

A Testament to Rome’s Cultural and Religious Legacy:

- Temple to All Gods: Originally dedicated to all the gods of Rome, the Pantheon reflects the rich religious traditions of the ancient world. Its circular design and open oculus symbolize a connection between the earthly and divine realms.

- Christian Church: Later consecrated as a Christian church in the 7th century, the Pantheon’s transformation highlights the continuity and evolution of religious beliefs in Rome.

- Burial Site of Renowned Figures: The Pantheon houses the tombs of notable figures, including the Renaissance artist Raphael and the first kings of Italy, further solidifying its importance in Italian history and culture.

A Global Tourist Destination:

- Millions of Visitors: The Pantheon draws millions of visitors each year who admire its architectural beauty, historical significance, and spiritual atmosphere.

- Cultural Exchange: It serves as a hub for cultural exchange, where people worldwide come together to appreciate a shared human heritage.

- Inspiration for Artists and Architects: The Pantheon inspires artists, architects, and designers who draw inspiration from its timeless design and innovative engineering.

The Pantheon is an enduring symbol of Rome’s rich history, architectural brilliance, and cultural heritage. Its resilience and continued relevance in the modern world make it a must-visit destination for anyone interested in exploring the wonders of ancient civilizations.

Hagia Sophia History

Hagia Sophia Church was built in 537 AD, with minarets added in the 15th–16th centuries (Wiki Image).

Here are ten quotes that capture the awe, wonder, and historical significance of the Hagia Sophia:

- Procopius (Byzantine historian): “The Emperor Justinian built a church so marvelous that human language is insufficient to describe it.”

- Justinian I (Byzantine Emperor): “Solomon, I have outdone thee!” (Upon seeing the completed Hagia Sophia, comparing it to the Temple of Solomon)

- Paulo Silenziario (Byzantine poet): “The dome seems not to be supported by solid masonry, but to cover the space with its golden vault, suspended from the heavens.”

- William Butler Yeats (Irish poet): “Hagia Sophia, that great cathedral where the Byzantine emperors were crowned, mosaics glimmering in the dim light, the scent of incense in the air.”

- Edith Wharton (American novelist): “The impression produced by the Hagia Sophia is one of amplitude and height…the mind is filled with a sense of space and majesty.”

- Pierre Loti (French novelist): “Hagia Sophia is not only the most beautiful monument in the world but also the most mysterious.”

- Edmondo De Amicis (Italian author): “The Hagia Sophia is a poem in stone, a hymn to the glory of God and the power of the human spirit.”

- John Ruskin (English art critic): “The Hagia Sophia is the most glorious work of Byzantine art, a masterpiece of architecture and decoration.”

- Robert Byron (British travel writer): “Hagia Sophia is a building that has seen it all, from the triumphs of emperors to the fall of empires.”

- Unknown: “Hagia Sophia is a living testament to the enduring power of faith, art, and human creativity.”

| Year | Event/Development |

|---|---|

| 532 | Construction begins on the current Hagia Sophia, commissioned by Emperor Justinian I after the previous church was destroyed during the Nika riots. |

| 537 | The Hagia Sophia is inaugurated on December 27th. It becomes the cathedral of Constantinople and the largest church in the world. |

| 553 & 558 | Earthquakes damage the dome. |

| 562 | The dome is rebuilt, slightly larger and higher than the original. |

| 7th Century | The Iconoclastic Controversy leads to the removal of some religious imagery. |

| 867 | A new mosaic of the Virgin and Child is installed in the apse. |

| 9th – 10th Centuries | The Hagia Sophia is a center of Byzantine religious and cultural life. |

| 1204 | The Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople. The Hagia Sophia was looted and damaged and converted into a Roman Catholic cathedral under Latin rule. |

| 1261 | The Byzantines recapture Constantinople, and the Hagia Sophia is restored to the Eastern Orthodox Church. |

| 1453 | Constantinople falls to the Ottoman Turks. <br> – Mehmed II converts the Hagia Sophia into a mosque. <br> – A minaret is added, and Christian imagery is covered. |

| 16th Century | – Large roundels with calligraphic inscriptions of Allah, Muhammad, and the first four caliphs are added. <br> – The minbar (pulpit) and mihrab (niche indicating the direction of Mecca) is installed. |

| 18th Century | Sultan Mahmud I commissions the construction of two libraries and a medrese (religious school). |

| 19th Century | – The Fossati brothers undertake major restoration work, uncovering some Byzantine mosaics. |

| 1934 | Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Republic of Turkey, ordered the Hagia Sophia to be secularized and turned into a museum. |

| 1985 | The Hagia Sophia is designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site as part of the Historic Areas of Istanbul. |

| 2020 | The Hagia Sophia was converted into a mosque by the Turkish government. |

Hagia Sophia: A Testament to Byzantine History, Engineering, and Architecture

Hagia Sophia, located in Istanbul, Turkey, is a Byzantine architectural and engineering masterpiece. It has been a cathedral, mosque, and museum for over 1,500 years. Its rich history and architectural grandeur make it a significant cultural and historical landmark.

History:

- First Construction (325-360 AD): Emperor Constantine the Great commissioned the initial church, known as the “Great Church” (Megale Ekklesia).

- Second Construction (415 AD): Rebuilt by Emperor Theodosius II after a fire, this structure was also destroyed during the Nika riots in 532 AD.

- Current Structure (537 AD): Emperor Justinian I ordered the construction of the current Hagia Sophia, designed by the mathematicians Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles. It became the seat of the Eastern Orthodox Church and the center of religious and political life in Constantinople.

- Ottoman Era (1453 AD): After the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople, Hagia Sophia was converted into a mosque. Minarets were added, and Christian mosaics were plastered over.

- Museum (1935-2020): Hagia Sophia was secularized and turned into a museum in 1935, showcasing its rich history and architectural significance.

- Mosque Again (2020-Present): In 2020, Hagia Sophia was reverted to a mosque, sparking international controversy and debate over its status.

Engineering:

- Massive Dome: The dome is Hagia Sophia’s most iconic feature. It spans 31 meters (102 feet) in diameter and appears to float effortlessly due to its ingenious design.

- Pendentives: Pendentives are triangular concave supports that allow the architects to transition from the square base of the structure to the circular base of the dome. This innovative solution was a breakthrough in architectural engineering.

- Buttresses and Half-Domes: Massive buttresses on the exterior and semi-domes on the interior support the main dome and create a sense of spaciousness and light.

- Materials: The construction of Hagia Sophia involved the use of bricks, mortar, stone, and marble. The bricks used for the dome were lighter than traditional bricks, reducing the structure’s overall weight.

Architecture:

- Byzantine Style: Hagia Sophia is a prime example of Byzantine architecture, characterized by its massive domes, pendentives, and rich mosaics.

- Roman Influence: The basilica plan of the church, with its nave and aisles, reflects the influence of Roman architecture.

- Islamic Influence: Following the Ottoman conquest, Islamic elements like minarets, calligraphic inscriptions, and a mihrab (prayer niche) were added to the building.

Hagia Sophia’s unique history, innovative engineering, and rich architectural style make it a timeless masterpiece and a symbol of cultural exchange between the East and West.

Hagia Sophia YouTube Video

- Why is Hagia Sophia so Important? The Whole History is Explained by Simply Explained

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v6BAPskdJXc

- Views: 302,974

- Hagia Sophia: Istanbul’s Ancient Mystery | Full Documentary | NOVA | PBS by NOVA PBS Official

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ENpKObiarw

- Views: 568,106

- Hagia Sophia: Through the ages by TRT World

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rqa0eXnDey4

- Views: 377,076

- It’s a church. It’s a mosque. It’s Hagia Sophia. – Kelly Wall by TED-Ed

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KRPp3jzv1Tw

- Views: 2,281,831

- Hagia Sophia – Istanbul’s Ancient Mystery (2014) | Full Documentary | NOVA by PBS America

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g1Wg2QkDGJw

- Views: 521,565

First Construction (325-360 AD): Emperor Constantine the Great commissioned the initial church, known as the “Great Church” (Megale Ekklesia). Second Construction (415 AD): Rebuilt by Emperor Theodosius II after a fire, this structure was also destroyed during the Nika riots in 532 AD.

The Hagia Sophia, a magnificent architectural marvel in Istanbul, Turkey, has a rich history that spans centuries and empires. Its construction and reconstruction reflect the region’s changing political and religious landscape.

First Construction (325-360 AD):

Emperor Constantine the Great, the first Christian Roman emperor, commissioned the initial church, the “Great Church” (Megale Ekklesia). This basilica-style structure, completed under his son Constantius II, was an important center of Christian worship in Constantinople, the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire.

Second Construction (415 AD):

Unfortunately, the Great Church was destroyed by fire during a popular uprising in 404 AD. Emperor Theodosius II ordered its reconstruction, and a new basilica was completed in 415 AD. This second structure featured a larger dome and a more elaborate interior, further solidifying its status as a symbol of imperial power and Christian faith.

Destruction During the Nika Riots:

Tragically, the second church was also destroyed in 532 AD during the Nika riots, a violent uprising against Emperor Justinian I. The riots caused widespread destruction in Constantinople, and the Hagia Sophia was not spared.

The Hagia Sophia’s turbulent early history is a testament to the challenges and upheavals the Eastern Roman Empire faced. However, the destruction of the second church paved the way for the construction of the iconic Hagia Sophia that we know today, a masterpiece of Byzantine architecture and engineering.

Current Structure (537 AD): Emperor Justinian I ordered the construction of the current Hagia Sophia, designed by the mathematicians Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles. It became the seat of the Eastern Orthodox Church and the center of religious and political life in Constantinople.

Originally a church, later a mosque, the 6th-century Hagia Sophia (532–537) by the Byzantine emperor Justinian the Great was the largest cathedral in the world for nearly a thousand years, until the completion of the Seville Cathedral (1507) in Spain (Wiki Image).

Current Structure (537 AD): After the destruction of the second church during the Nika riots, Emperor Justinian I was determined to rebuild the Hagia Sophia with even greater magnificence. He commissioned the mathematicians Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles to design a new structure surpassing grandeur and beauty.

The architects combined elements of the basilica and central-plan churches, creating a unique and innovative design that would become a hallmark of Byzantine architecture. The most striking feature of the new Hagia Sophia was its massive dome, which seemed to float above the vast interior space.

The construction of the current Hagia Sophia was completed in an astonishingly short period of five years, a testament to the resources and determination of Emperor Justinian I. The church became the seat of the Eastern Orthodox Church and the center of religious and political life in Constantinople.

The Hagia Sophia’s grandeur and beauty were intended to reflect the power and majesty of the Byzantine Empire. It served as a symbol of the empire’s wealth, technological prowess, and artistic achievements. The church also played an essential role in religious ceremonies and rituals, hosting coronations, processions, and other important events.

The Hagia Sophia’s current structure is a testament to the vision and ambition of Emperor Justinian I and the ingenuity of its architects. Its innovative design, blending elements of the basilica and central-plan churches, and its awe-inspiring dome have captivated visitors for centuries. It is a monument to the enduring legacy of the Byzantine Empire and a testament to the power of human creativity and engineering.

Ottoman Era (1453 AD): After the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople, Hagia Sophia was converted into a mosque. Minarets were added, and Christian mosaics were plastered over.

Ottoman Era (1453 AD):

The Hagia Sophia underwent a significant transformation after Sultan Mehmed II’s 1453 Ottoman conquest of Constantinople. It was converted into a mosque, reflecting the new Islamic rule in the city.

Several changes were made to the Hagia Sophia during the Ottoman era:

-

- Conversion to Mosque: The Christian altar, bells, and iconostasis were removed. A mihrab (niche indicating the direction of Mecca) and a minbar (pulpit) were added to facilitate Islamic worship.

-

- Minarets: Four minarets were constructed around the Hagia Sophia, becoming iconic symbols of the city’s skyline. These slender towers were used for the call to prayer, signaling the change in the building’s religious function.

-

Covering of Mosaics: The Christian mosaics depicting Jesus, Mary, and other figures were plastered over to comply with Islamic beliefs, prohibiting the depiction of human figures in religious contexts. However, some mosaics were later uncovered and restored during the 20th century.

-

Structural Modifications: The Ottomans made some structural modifications to the Hagia Sophia, including adding buttresses to reinforce the dome and building a library and other facilities.

The conversion of the Hagia Sophia into a mosque marked a turning point in its history. It became a symbol of Ottoman power and Islamic dominance in the region. Despite the changes to the building, its architectural grandeur and historical significance remained intact, making it a revered monument for Muslims and Christians.

Museum (1935-2020): Hagia Sophia was secularized and turned into a museum in 1935, showcasing its rich history and architectural significance. Mosque Again (2020-Present): In 2020, Hagia Sophia was reverted to a mosque, sparking international controversy and debate over its status.

Hagia Sophia Timeline (continued):

-

- Museum (1935-2020): In 1935, under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of modern Turkey, the Hagia Sophia was secularized and turned into a museum. This decision aimed to showcase the building’s rich history and architectural significance, allowing visitors worldwide to appreciate its unique blend of Byzantine and Ottoman heritage.

During this period, extensive restoration was undertaken to reveal the building’s original mosaics and other historical features that had been hidden or altered during its time as a mosque. The Hagia Sophia Museum became one of Istanbul’s most popular tourist attractions, drawing millions of visitors annually.

-

- Mosque Again (2020-Present): In 2020, the Turkish government, led by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, decided to revert the Hagia Sophia to a mosque. This move sparked international controversy and debate, with some praising the decision as a reclamation of Turkey’s Islamic heritage. In contrast, others criticized it as threatening the building’s historical and cultural significance.

The conversion to a mosque involved reinstalling Islamic features such as the mihrab and minbar and covering some Christian mosaics during prayer times. The decision has been met with mixed reactions both domestically and internationally, with ongoing discussions about the balance between religious freedom, cultural heritage preservation, and the geopolitical implications of the Hagia Sophia’s status.

Massive Dome: The dome is Hagia Sophia’s most iconic feature. It spans 31 meters (102 feet) in diameter and appears to float effortlessly due to its ingenious design. Pendentives: Pendentives are triangular concave supports that allow the architects to transition from the square base of the structure to the circular base of the dome. This innovative solution was a breakthrough in architectural engineering.

The Hagia Sophia’s massive dome is truly its most iconic feature. Spanning 31 meters (102 feet) in diameter, the dome is a marvel of Byzantine engineering and architectural innovation.

The dome’s impressive size and seemingly weightless appearance are due to several ingenious design elements:

-

Pendentives: The dome rests on four triangular concave pendentives, which transition the structure’s square base to the dome’s circular base. This innovative solution allows for a larger and more stable dome than earlier designs.

Hagia Sophia pendentives -

Windows: A ring of 40 windows encircles the dome’s base, creating the illusion that the dome is floating on a halo of light. The windows also provide ample natural light to illuminate the interior.

Hagia Sophia dome windows -

Lightweight Materials: The dome is constructed with lightweight materials, such as pumice stone, to reduce weight. This, combined with using pendentives and buttresses, helps distribute the dome’s weight evenly and ensures its structural integrity.

The Hagia Sophia’s dome is a feat of engineering and a symbol of the Byzantine Empire’s power and technological prowess. It has inspired countless architects throughout history and continues to be a source of wonder and admiration for visitors worldwide.

Buttresses and Half-Domes: Massive buttresses on the exterior and semi-domes on the interior support the central dome and create a sense of spaciousness and light.

The Hagia Sophia’s massive dome is not only a marvel of engineering but also a testament to the architectural ingenuity of its designers. The dome’s stability and grandeur are achieved through buttresses, half-domes, and pendentives.

Buttresses: The exterior of the Hagia Sophia features massive buttresses that act as counterforts, supporting the dome’s weight and preventing it from collapsing outwards. These brick and stone buttresses are strategically placed around the dome’s base to distribute its weight evenly and ensure its structural integrity.

Half-Domes (Semi-Domes): Two large half-domes flank the central dome on the interior, further supporting its weight and creating a sense of spaciousness and grandeur. These half-domes, located on the nave’s east and west ends, also help distribute the light from the dome’s windows throughout the interior, creating a luminous and ethereal atmosphere.

Pendentives: As mentioned earlier, the dome rests on four triangular concave pendentives, which transition the square base of the structure to the circular base of the dome. This innovative solution creates a more enormous, stable dome and a visually stunning architectural element.

Combining buttresses, half-domes, and pendentives creates a harmonious and structurally sound system supporting the Hagia Sophia’s massive dome. This ingenious design ensures the building’s longevity and enhances its aesthetic appeal, creating a sense of awe and wonder for visitors.

Materials: The construction of Hagia Sophia involved the use of bricks, mortar, stone, and marble. The bricks used for the dome were lighter than traditional bricks, reducing the structure’s overall weight.

The construction of the Hagia Sophia involved a diverse range of materials, each chosen for its specific properties and contributions to the overall structure:

- Bricks: Brick was the primary building material used in the Hagia Sophia. Millions of bricks were used to construct the building’s walls, arches, and domes. The bricks were made from locally sourced clay and fired in kilns, making them durable and fire-resistant.

-

Mortar: A mixture of lime, sand, and water was used as mortar to bind the bricks together. The mortar played a crucial role in the structural integrity of the Hagia Sophia, ensuring that the bricks remained firmly in place.

-

Stone: Large stone blocks, such as granite and porphyry, were used for the columns, foundations, and decorative elements. These stones were quarried from various locations around the Roman Empire and transported to Constantinople to construct the Hagia Sophia.

- Marble: The interior of the Hagia Sophia was adorned with colorful marble, adding to its opulence and beauty. The marble was sourced from different empire regions, including Greece, Egypt, and North Africa. It was used for columns, floors, walls, and other decorative elements.

- Lightweight Bricks for the Dome: The dome bricks were designed to be lighter than traditional bricks. This was achieved by adding crushed brick and other lightweight materials to the clay mixture. The use of lighter bricks reduced the overall weight of the dome, making it easier to support and less prone to collapse.

The Hagia Sophia’s architects and engineers carefully selected and combined these materials to create a building that was not only structurally sound but also aesthetically pleasing. Different materials, textures, and colors created a visually stunning interior that reflected the wealth and power of the Byzantine Empire.

Byzantine Style: Hagia Sophia is a prime example of Byzantine architecture, characterized by its massive domes, pendentives, and rich mosaics.

Hagia Sophia is a prime example of Byzantine architecture, a style that flourished during the Eastern Roman Empire and left a lasting legacy on religious architecture worldwide. Critical features of Byzantine architecture, as exemplified by Hagia Sophia, include:

-

Massive Domes: The most iconic feature of Byzantine architecture is the dome, often supported by pendentives, triangular curved sections that transition from a square base to a circular dome. The dome of Hagia Sophia is imposing, spanning 31 meters (102 feet) in diameter and creating a sense of awe and grandeur within the vast interior space.

Hagia Sophia massive dome -

Pendentives: The use of pendentives is a hallmark of Byzantine architecture. These architectural elements allow for the construction of larger and more stable domes, as they evenly distribute the dome’s weight onto the supporting piers.

Hagia Sophia pendentives -

Rich Mosaics: Byzantine churches are renowned for their intricate and colorful mosaics, often depicting religious scenes, biblical figures, and emperors. The mosaics in Hagia Sophia are particularly well-preserved and offer a glimpse into the artistic and spiritual traditions of the Byzantine Empire.

Hagia Sophia rich mosaics -

Centralized Plan: Byzantine churches often followed a centralized plan, with the dome as the central focus of the space. This design creates a sense of unity and symmetry, emphasizing the dome’s spiritual importance as a symbol of heaven.

-

Use of Light: Byzantine architects created a dramatic and mystical atmosphere within their churches. The dome of Hagia Sophia, with its ring of 40 windows, allows natural light to flood the interior, creating an ethereal glow that enhances the spiritual experience.

Hagia Sophia’s unique blend of architectural elements, innovative engineering, and rich artistic decoration make it a masterpiece of Byzantine architecture. Its influence can be seen in countless religious buildings around the world, from the mosques of Istanbul to the cathedrals of Europe.

Roman Influence: The basilica plan of the church, with its nave and aisles, reflects the influence of Roman architecture.