Michelangelo is Royal Blue.

Introduction

“And God said, Let there be light.

And God saw the light, that was good,” The Holy Bible.

Wrote a painter-biographer Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of Painters, Sculptures, and Architects:

“The Almighty Creator took pity on their often fruitless labor. He resolved to send Earth a spirit capable of supreme expression in all the arts, giving form to painting, sculpture, perfection, and architectural grandeur. The Almighty Creator also graciously endowed this chosen one with an understanding of philosophy and poetry’s grace.”

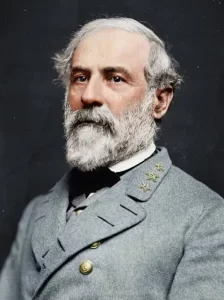

To all of Europe, Michelangelo fulfilled the concept of the “Universal Man,” a man who knew all. They called Him “The Divine Michelangelo.”

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (Wikipedia Image)

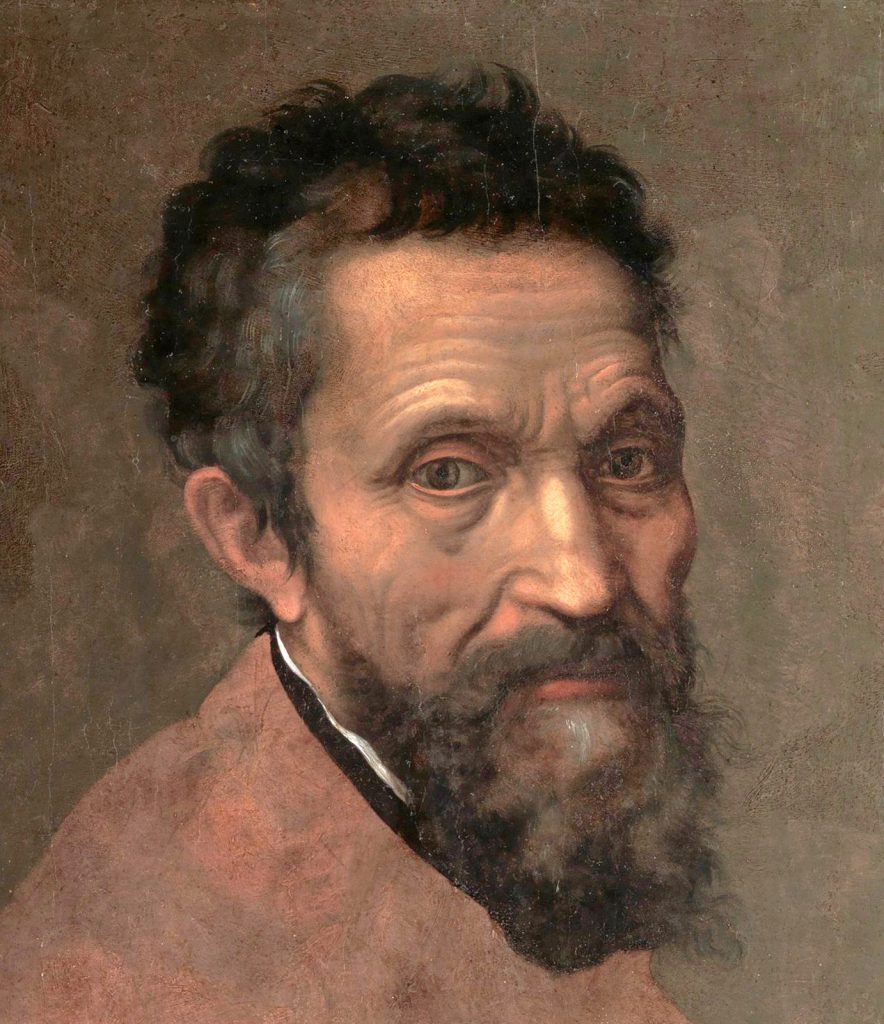

“After Antonio da Sangallo died in 1546,” says Vasari, “and as there was no one who directed the factory of Saint Peter, there were different opinions until His Holiness, inspired by God, decided to entrust it to Michelangelo, who refused to say, to excuse himself from that burden, that his art wasn’t that of architecture. Finally, not admitting his scruples, the Pope ordered him to accept it, and so much against his will, he had to be in charge of that endeavor.”

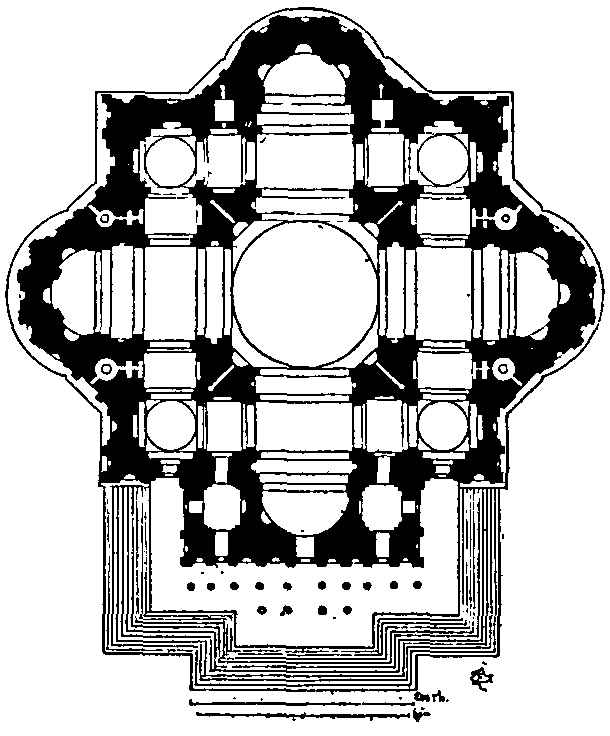

19th-century drawing of St. Peter’s Basilica around 1450, Missing the Dome (Wikipedia Image)

19th-century drawing of St. Peter’s Basilica around 1450, Missing the Dome (Wikipedia Image)

Vasari said, ”To dispel all suspicion of sordidness, Michelangelo demanded that in the motu proprio (an edict personally issued by the Pope) in which he was appointed director of the works with full authority to do and undo, add, and remove, it should be noted that he served the church without any reward (monetary) and just for the love of God. Pope Paul III, who saw in the glorious sculptor the genius appropriate to finish the work, always supported Michelangelo against the intrigues of his enemies.”

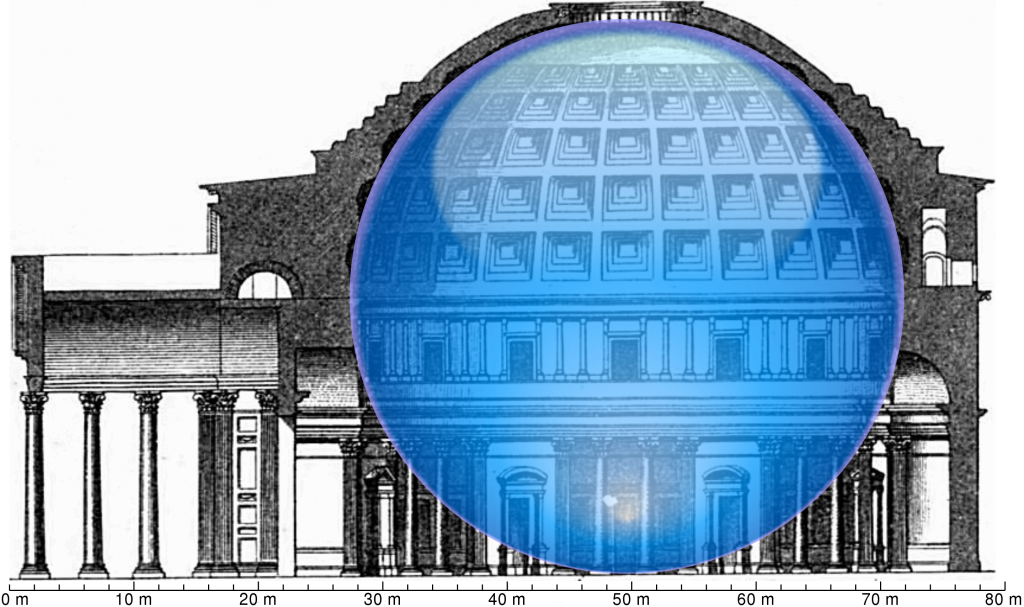

Michelangelo knew where to start with St. Peter’s architecture—the ancient Roman Pantheon dome! He said of the Pantheon that it was “an angelic and not a human design.”

Michelangelo considered raising the Pantheon dome twice as high. He also planned to enlarge the four piers at the crossing that braced the crown and upgrade the thickness of St. Peter’s edge.

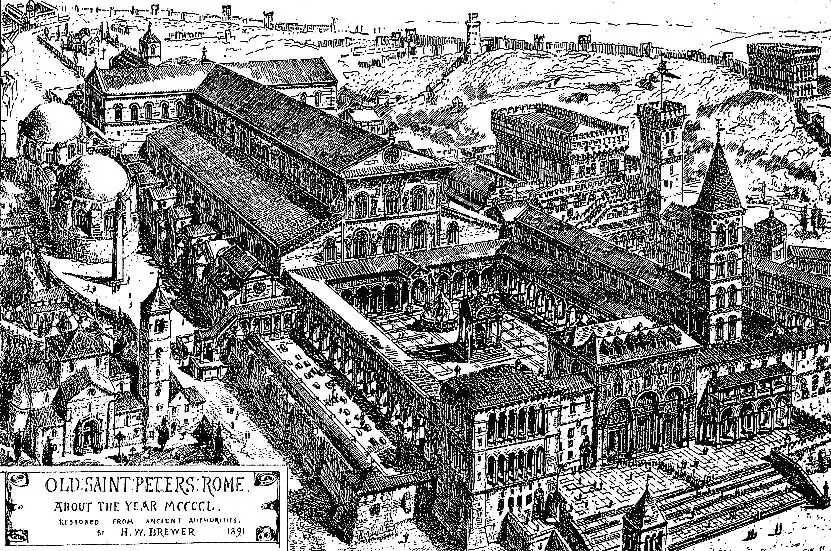

Michelangelo’s Plan (Wikipedia Image)

Michelangelo’s Plan (Wikipedia Image)

One of Michelangelo’s biggest challenges was the problem of “God’s peculiar light.” The oculus, or opening, in the center of the Pantheon dome is 27 feet in diameter. It allows sunlight to stream into the building, creating a dramatic effect. Michelangelo sought to create a similar impact on the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, but he recognized that he would need to make adjustments to reflect the symbol of God’s presence. He said, “The true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection.“

Michelangelo and Pantheon Oculus or Sundial

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, a bearded man with deep brown eyes, lay asleep, surrounded by the giant sculptures and unfinished sketches that defined his connection to the divine. His old, paint-stained clothes clung to him like a second skin, a testament to his singular dedication to his art. Although his life had been long and filled with glory, he had never married, devoting his soul to his work and faith.

Suddenly, a knock on the door startled him awake. Groggy and irritable, he sat up, shouting toward the door, “I’ll have to change!” With a sigh, he disrobed, tossing aside his worn garments, and replaced them with something more suitable for his journey from the Pantheon. The air carried the faint odor of sweat and stone dust, so Michelangelo dabbed on perfume to mask the scent before swinging open the door to face his visitor.

“We’ll see the Pantheon!” exclaims Trickyoulo, Michelangelo’s good friend. He is fat, jolly, clever, and in his mid-30s.

“I want to see what the Pantheon was like in ancient Roman times,” remarked Michelangelo as he left the door with Trickoulo.

“Yes, with you, Michelangelo, it will be enjoyable to see what it was like when it first opened around 125 AD,” said Trickyoulo.

They cross the Vatican over the Tiber River by the Castle of Sant‘Angelo and head towards the Pantheon.

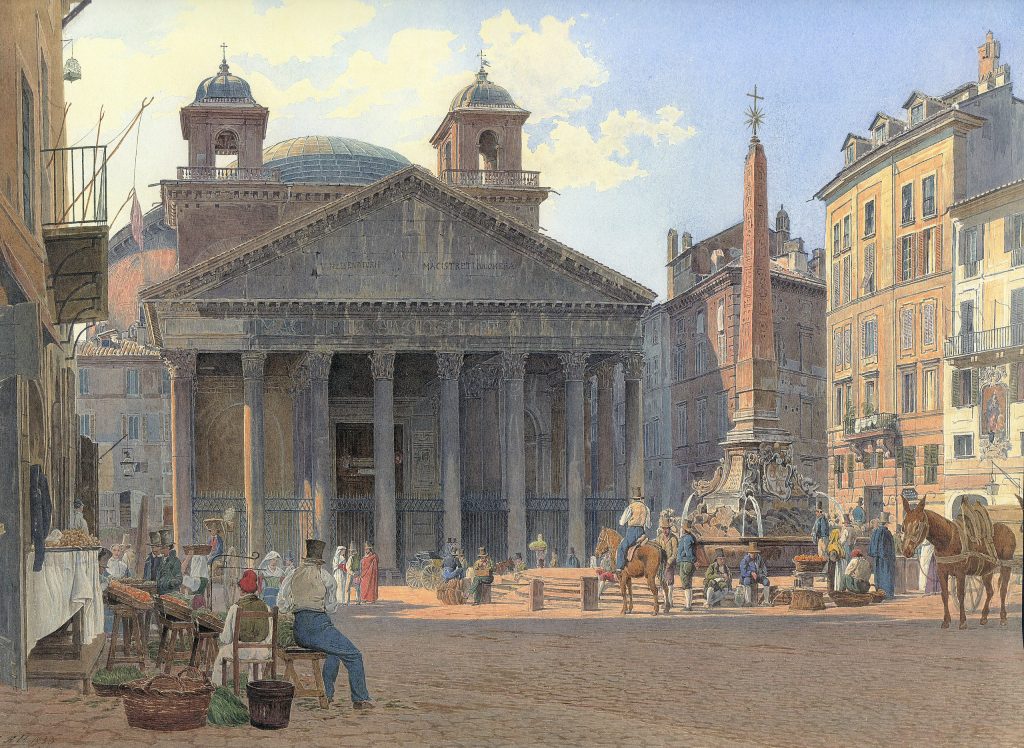

After about 15 minutes, they arrive at an imposing sight! The Pantheon has a modillion, and across the large granite Corinthian columns, in enormous letters, was the Latin inscription:

M. AGRIPPA L.F. COS TERTIUM FECIT

In English, this means: “Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, a three-time consul, made this.”

The Pantheon Outside (Wikipedia Image)

“Apollodorus of Damascus made it,” said Trickyoulo.

“All the columns of Rome have fallen in the Forum and frayed elsewhere in Rome. I wonder what makes them stand up so tall?” questions Michelangelo.

“Diogenes and Caryatides of Athens designed and decorated the columns, which are looked upon as masterpieces of excellence,” said Trickyoulo proudly.

“The Pantheon was abandoned and plundered in the 5th and 6th centuries, particularly during the Visigoths’ sack of Rome. In 609, the Byzantine emperor Phocas offered the Pantheon to Pope Boniface IV, who reconsecrated it as the Church of Mary of the Martyrs [Sancta Maria ad Martyres]. This saved the Pantheon from dark ages and medieval period abandonment and destruction,” said Trickyoulo.

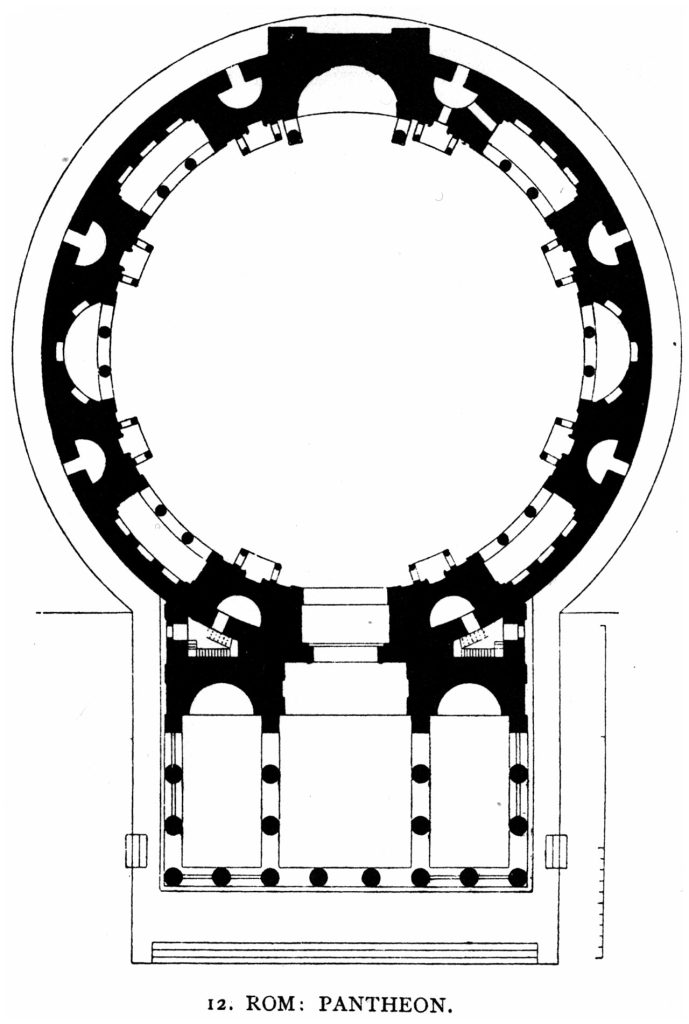

They walk in through two bronze doors, measuring 12 x 7.5 meters, and proceed. What strikes the eye is this enormous dome, or rotunda, built in 125 BC. Its diameter of 43 meters equals the dome’s height, hence the impression of harmony emanating from the temple.

“It is necessary to keep one’s compass in one’s eyes, not in hand, for the hands execute, but the eye judges,” said Michelangelo.

Its diameter equals the height of the dome. (Wikipedia Image)

“The Pantheon’s dome weighs 4,535 tonnes, which is still the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome! Of course, the largest reinforced dome is Brunelleschi’s dome of the Duomo of Florence, completed in 1436,” said Trickyoulo.

Michelangelo and Trickyoulo immediately look up to the top of the Pantheon. A sizable round shape, 8.8 meters in diameter, is the oculus (or giant eye) atop the Pantheon’s dome. It’s the only direct light source inside the Pantheon, and the Oculus lets in the rain, storms, clouds, or sunlight from the outside. Sunshine is coming in today.

“Which explains the chiaroscuro (the treatment of light and shade in drawing and painting) that reigns in the building,” said Michelangelo.

The interior of the 18th-century Pantheon (Wikipedia Image)

The interior of the 18th-century Pantheon (Wikipedia Image)

“Farther from the oculus, there is a grey dome, about three times the size of the oculus. The grey dome is ancient, with a jagged dark or light grey line. In the line down the dome, there are twenty-seven square notches. Five ever-expanding squares lead down from the oculus. Apollodorus added these squares to bring lightness to the dome,” explained Trickyoulo.

“Imagine, the dome was covered in sheets of Syracusan bronze, but Constans II removed these in 663 AD,” said Trickyoulo.

Interior of the Pantheon (Wikipedia Image)

“What other decorations did the dome have in ancient times?” asked Michelangelo.

“In the middle of each square, there was a single large oak or olive leaf of varying color,” said Trickyoulo. “The interior features sunk coffers [panels], which originally contained bronze star decorations. Notice the Pantheon portico ceiling and the beams are still gilded with bronze.”

Michelangelo is a sculptor, painter, and architect who quickly imagined this on the dome.

“But in my opinion, it resembles the heavens because of its vaulted roof,” whispers Trickyoulo.

“What made the dome stand?” asked Michelangelo.

“There are two things. One is the drum. The drum wrapped around the dome spans seven meters and rises to almost the dome’s height,” said Trickyoulo. “The weight of the drum forces the lateral support of the dome.”

“The second thing is the lightness of the dome. The lower levels used heavy crushed brick, the medium levels used limestone tufa, and the upper levels used volcanic pumice, the lightest concrete known to the ancients,” said Trickyoulo.

“The lightest concrete in the past and now!” exclaimed Michelangelo, thinking about using that material in St. Peter’s Basilica dome.

“And a small band of crushed brick around the oculus,” said Trickyoulo.

Michelangelo notices an alcove, or nook, opposite the door. This nook is the most impressive, reaching the ceiling. He also notes that the original pavement features a square pattern composed of grey granite, red porphyry, Phrygian purple marble, and Numidian yellow.

The Nook on the Floor in Modern Times (Wikipedia Image)

“I wonder what the statues on the floor looked like to the Romans? The Pantheon was an ancient pagan temple to all the gods,” said Michelangelo.

“Yes, the Pantheon contained statues of the twelve gods and could have even contained a sculpture of Julius Caesar. Pliny the Younger told an interesting story about the statue of Venus, and he said that ‘one of Cleopatra’s rare pearls was cut in half so that each half might serve as pendants for the ears of Venus,’” said Trickyoulo.

Michelangelo stares at the oculus at the top.

“I must say that on a sunny day, that is a great sundial, a chronoscope, at the top of the dome,” said Michelangelo.

Sundial of the Pantheon (Wikipedia Image)

Sundial of the Pantheon (Wikipedia Image)

“Hadrian, the Roman Emperor, was so impressed that he transferred the senate from the Roman Forum to the Pantheon!” said Trickyoulo.

“This oculus spotlight bathes the entrance with light rays yearly at noon on the Roman birthday of April 21. Emperor Hadrian was to be present at the inauguration of the building on April 21, so he decided to arrive at precisely noon at the entrance and get bathed with light!” said Trickyoulo.

After meeting with Trickyoulo, Michelangelo begins to think about the great sundial at the Pantheon. He visits the Pantheon several times to relive this experience.

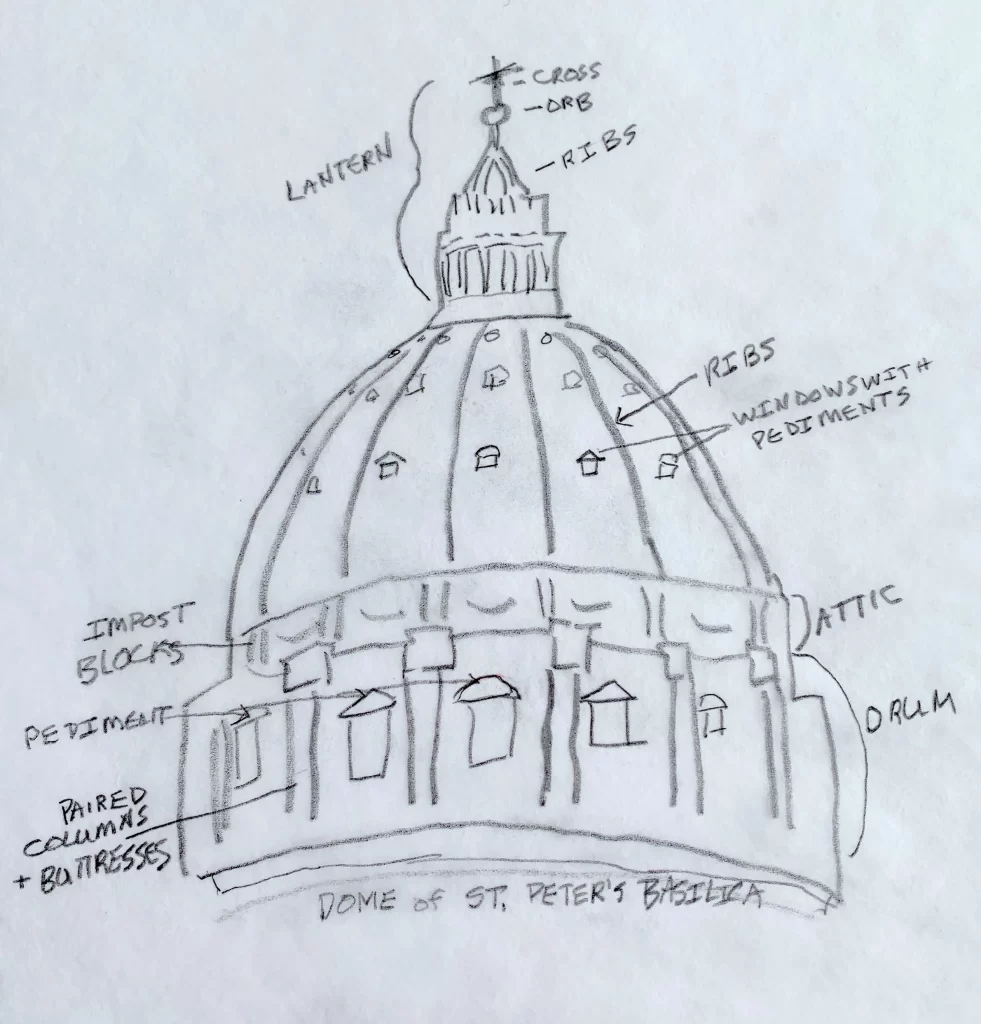

Saint Peter’s Dome

Later, Michelangelo had a dream. In this dream, the dome of Saint Peter’s looms before him. Suddenly, the dome is complete! Instead of sunlight bathing him with a Pantheon sundial, three lights loomed before him, separated by three widows in Michelangelo’s dream: The Father, My Son, and the Holy Ghost! This created a sense of awe and wonder, reminding the faithful that God was present in their midst.

Crepuscular Three-light Rays in St. Peter’s Basilica: The Father, My Son, and the Holy Ghost (Wikipedia Image)

Crepuscular Three-light Rays in St. Peter’s Basilica: The Father, My Son, and the Holy Ghost (Wikipedia Image)

Michelangelo awoke, his mind still lingering on the vivid remnants of a dream. In it, beams of light had streamed through the dome of the Basilica, forming three perfect spots on the floor below. The vision was captivating, yet one problem gnawed at him: how could he ensure that exactly three light portals would remain on the Basilica’s floor, no matter the sun’s angle when it was high in the sky on a clear day?

His mind raced through the dome’s geometry, the interplay of sunlight and architecture. Suddenly, the solution dawned on him. If he placed a series of light portals evenly around the dome’s base, he could control the flow of sunlight. He could create a rhythm of light and shadow by spacing three portals every 22.5 degrees and dividing the full dome circle into 16 segments (360 divided by 16). Large, square windows covering about a third of each segment’s distance would allow the light to enter at just the right angles, ensuring that three beams would always strike the floor, regardless of the sun’s position in the sky!

Saint Peter’s Dome: Note the Windows and the Base of the Dome (Wikipedia Image)

Saint Peter’s Dome: Note the Windows and the Base of the Dome (Wikipedia Image)

Excited by his revelation, Michelangelo dashed out to tell Pope Paul III, the Holy Seer. The two finally met at the imagined dome of St. Peter’s Basilica. Still inspired by his dream, Michelangelo detailed his vision of the three light portals and the ingenious design. The Pope stood before the grand crown of the Basilica, his gaze fixed on the unfinished dome. He opened and closed his eyes as if trying to see the future structure in all its glory. Minutes passed in silence before Pope Paul III, overwhelmed by the beauty and possibility of Michelangelo’s dream, began to weep with wonder.

But even in this moment of triumph, Michelangelo bore a quiet sadness. He knew he would never live to see the completed Basilica, a project far larger than anyone’s lifetime. For the first 40 years of construction, the work was led by a series of chief architects—Bramante, Maderno, and Bernini—before Michelangelo took over at the age of 71. Though he worked at St. Peter’s for only 18 years, he left an indelible mark. His greatest contribution was the drum, the decisive foundation on which the dome would rise. Even though he never saw its completion, his vision shaped the sacred structure for generations to come. It would take 150 years to finish St. Peter’s, a masterpiece built by many hands but forever bearing the spirit of Michelangelo.

Architectural terms for St. Peter’s Basilica Dome from Gerriann Brower (www.italianartfortravelers.com/post/the-old-man-and-the-dome)

Architectural terms for St. Peter’s Basilica Dome from Gerriann Brower (www.italianartfortravelers.com/post/the-old-man-and-the-dome)

It was twice as high as the Pantheon’s dome. Yet, Michelangelo made his dome 1.5 meters narrower in diameter than the Pantheon. Michelangelo said, “I could build one bigger, but not more beautiful, than that of the Pantheon.”

Michelangelo Buonarroti, one of the most renowned figures of the Renaissance, was a master in multiple fields of art. He sculpted iconic works like Moses and the Pietà, both celebrated for their emotional depth and technical perfection. As a painter, his work on the Sistine Chapel ceiling and The Last Judgment left an indelible mark on Western art with its powerful depictions of biblical scenes and human anatomy. Michelangelo also made significant contributions to architecture, notably as the architect behind the Dome of Saint Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City.

He passed away on February 18, 1564, just shy of his 89th birthday, leaving behind a legacy that shaped the future of art and architecture for centuries to come.

History up to the Present Day

The Pantheon

During Pope Urban VIII’s reign from 1623 to 1644, the Pope ordered the Pantheon’s portico bronze ceiling and the beams to be melted down. The bronze was used for two things:

- To make cannons for the Castel Sant’Angelo’s fortification.

- At the artist Barberini’s request to the Pope, the great Baldacchino in St Peter’s Basilica, right in the middle of St. Peter’s rising dome. Hence the famous maxim: “What the barbarians did not do [was removing the bronze from the Pantheon], the Barberini did.”

Bernini’s Baldacchino (Wikipedia Image)

Bernini’s Baldacchino (Wikipedia Image)

In the early 1600s, Pope Urban VIII Barberini tore away the bronze ceiling of the entrance and replaced that with the infamous Twin Towers, which were removed in the late 1800s.

The Twin Bell Towers, or what they were called by the Roman populace, “the Ass’s Ears.” (Wikipedia Image)

The Twin Bell Towers, or what they were called by the Roman populace, “the Ass’s Ears.” (Wikipedia Image)

After nearly 2,000 years, the Pantheon in Rome, with its magnificent dome and oculus, remains in excellent condition, showcasing the brilliance of Roman engineering. Built during the reign of Emperor Hadrian around 126 AD, the Pantheon’s dome is still the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world. The oculus, a central opening at the dome’s peak, allows light to flood the interior and is a striking architectural feature.

The building’s longevity is attributed to the Romans’ innovative materials and techniques, including concrete mixed with lighter volcanic materials as the dome rose. Its survival through centuries of weather, earthquakes, and changing uses demonstrates the extraordinary skill and vision of Roman builders. Today, the Pantheon continues to inspire architects and engineers alike.

The Pantheon YouTube Video

- The Pantheon of Ancient Rome (Urbanist) – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ISeprrRDNsw – 1,564,485 views

- History Summarized: The Pantheon (Overly Sarcastic Productions) – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bd68UWTCur8 – 538,891 views

- Pantheon of Rome. Mystery of ancient Roman architecture in 3D (Andres Jalak) – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yn2XdZfx93w – 181,860 views

- The Pantheon – Under the Dome (Naked Science) – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-aDhzQMIGCY – 205,636 views

- Rome, Italy: The Pantheon – Rick Steves’ Europe Travel Guide – Travel Bite (Rick Steves’ Europe) – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ExwRrjE4kRQ – 195,552 views

Saint Peter’s Dome

Giacomo della Porta and Domenico Fontana completed St. Peter’s Dome in 1590. Decorating the inside of Michelangelo’s dome in Latin:

“TU ES PETRUS ET SUPER HANC PETRAM AEDIFICABO ECCLESIAM MEAM, ET TIBI DABO CLAVES REGNI CAELORUM.”

In English, this means: “You are Peter, and on this rock, I will build my church, and to you, I will give the keys of the kingdom of the heavens.”

St. Peter’s Dome (Wikipedia Image)

St. Peter’s Dome (Wikipedia Image)

In the early 18th Century, minor problems arose. The dome started cracking. When the support for a massive dome is insufficient, the sides move outward, and cracks appear throughout the base. Iron crossbeams fixed that.

St. Peter’s During the Night (Wikipedia Image)

St. Peter’s During the Night (Wikipedia Image)

Today, St. Peter’s is one of the most spectacular sights on the planet! To access the dome, you must climb 551 narrow (unsuitable for claustrophobics) steps, although you can take the elevator and “only” have to climb 320.

In 2023, eight euros if you choose to walk up or 10 euros if you want to use the elevator. You can buy the entrance ticket inside St. Peter’s.

Saint Peter’s Dome YouTube Video

- Visiting St. Peter’s Basilica + Dome Climb 2024 (The Tour Guy) – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a76p3lEWR-8 – 27,255 views

- Let’s Climb the Dome of St Peter’s Basilica! Step by step – literally! (RomeWise) – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B82ubnugwHI – 26,024 views

- Private tour inside St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City (CBS Evening News) – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mArcBezkqBI – 119,312 views

- Climb to St Peter’s Basilica Dome (Real Rome Tours) – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q_Hs_ZrL8qY – 25,345 views

- Best Way To Climb Michelangelo’s Dome of the St. Peter’s Basilica (The Tour Guy) – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qMtY0DotfsM – 38,752 views