Herodotus, Thucydides, and Plutarch

Okay, let’s break down these three immensely influential figures from ancient Greece who are known primarily for their historical and biographical writings:

- Herodotus (c. 484 – c. 425 BC):

- Title: Often called the “Father of History.”

- Significant Work: The Histories, an ambitious account primarily focused on the causes and events of the Greco-Persian Wars (early 5th century BC).

- Approach & Style:

- Inquiry-Based: His work embodies the Greek word historia (inquiry). He traveled extensively, collecting stories, eyewitness accounts, oral traditions, myths, and geographical/ethnographic information.

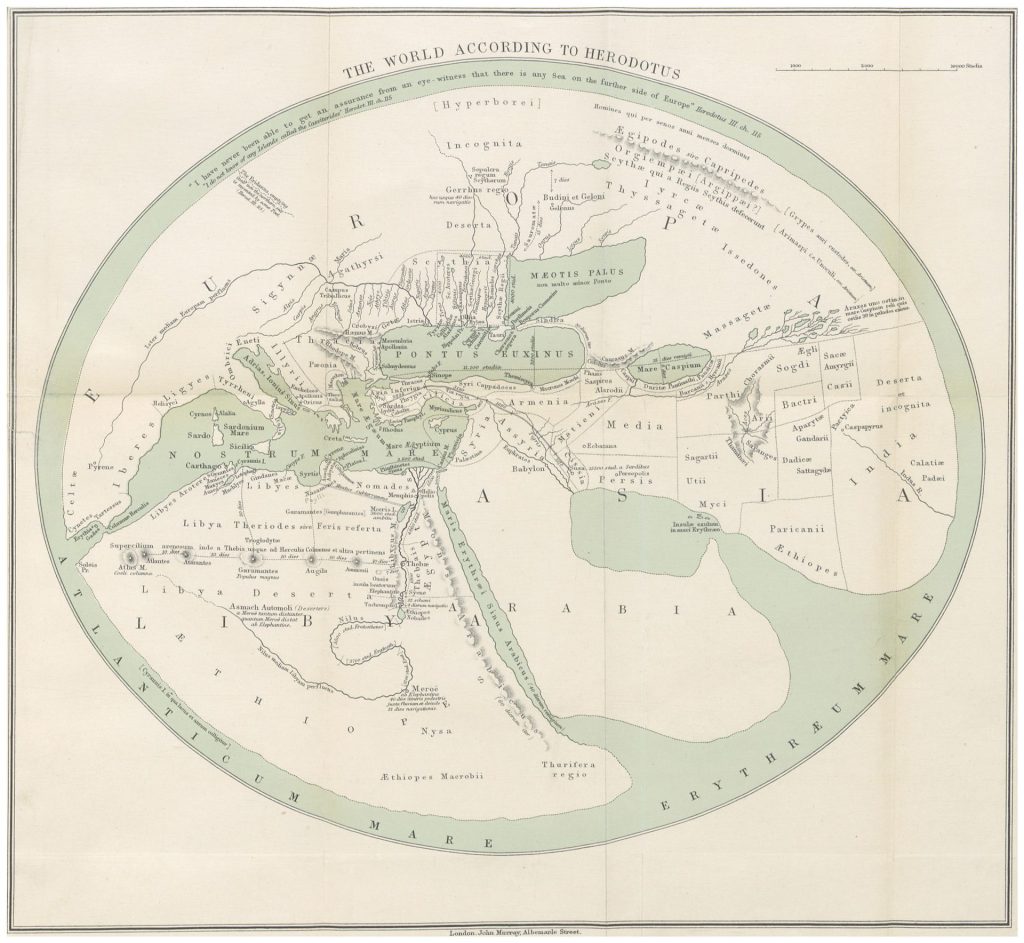

- Broad Scope: Included descriptions of different cultures (Egyptians, Persians, Scythians, etc.), geography, legends, and anecdotes alongside political and military history.

- Divine Intervention: Attributed events partly to fate and the actions of the gods.

- Narrative Style: Wrote in an engaging, often digressive, storytelling style.

- Goal: To preserve the memory of great deeds (Greek and “barbarian”) and explain the causes of the conflict between the Greeks and Persians.

- Legacy: Established history as a distinct literary genre. While sometimes criticized for including hearsay or mythical elements, he pioneered the large-scale historical narrative and preserved invaluable cultural information.

- Thucydides (c. 460 – c. 400 BC):

- Title: Often considered the “Father of Scientific History” or “Political Realism.”

- Significant Work: History of the Peloponnesian War, a detailed account of the war between Athens and Sparta (late 5th century BC). He was an Athenian general who participated in the war before being exiled.

- Approach & Style:

- Rigorous & Analytical: Focused on the Peloponnesian War, aiming for accuracy and objectivity.

- Exclusion of the Divine: Excluded supernatural explanations, focusing solely on human actions, political factors, and rational causation.

- Critical Use of Sources: Emphasized eyewitness accounts and critically evaluated evidence.

- Reconstructed Speeches: Included detailed speeches (which he admitted were reconstructed based on his understanding of what was likely said) to analyze the motivations and arguments of key figures.

- Dense & Analytical Style: His writing is often thick, complex, and focused on political and military analysis.

- Goal: To provide a precise, objective account of the war that would be useful for understanding the nature of power, politics, and human behavior in conflict (“a possession for all time”).

- Legacy: Set a new standard for historical methodology, emphasizing objectivity, rational analysis, and critical use of evidence. His work profoundly influenced political science and international relations theory.

- Plutarch (c. 46 – c. 120 AD):

- Title: Renowned biographer and moral philosopher.

- Major Works:

- Parallel Lives: A series of biographies comparing famous Greeks and Romans (e.g., Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar, Demosthenes and Cicero) to highlight their moral virtues and vices.

- Moralia: A collection of ethical, philosophical, and literary essays.

- Approach & Style:

- Biographical Focus: Primarily interested in individual lives and character, not constructing a narrative history of events.

- Moral Purpose: His main goal was ethical instruction, providing moral examples (both positive and negative) for his readers.

- Anecdotal: Relying heavily on anecdotes and personal details to reveal character.

- Engaging Style: Wrote in an accessible and engaging style.

- Time Period: Crucially, Plutarch lived much later than Herodotus and Thucydides during the Roman Empire. He wrote about figures from the distant past, relying on earlier historical sources.

- Legacy: He was immensely influential throughout Western history. His Parallel Lives was a primary source for Shakespeare’s Roman plays and deeply influenced European and American ideas about classical virtue and leadership for centuries. He shaped how later generations viewed many famous figures of antiquity.

Key Differences Summarized:

| Feature | Herodotus | Thucydides | Plutarch |

| Genre | History (broad narrative) | History (focused political/military) | Biography & Moral Philosophy |

| Time | 5th Century BC | 5th Century BC | 1st-2nd Century AD (Roman Era) |

| Primary Goal | Preserve memory, explain causes | Accurate account, political lessons | Moral instruction, character study |

| Scope | Wide-ranging (wars, culture, myth) | Focused (Peloponnesian War) | Individual Lives (paired Greeks/Romans) |

| Methodology | Inquiry, inclusive (oral/myth) | Analytical, critical, secular | Anecdotal, focused on character |

| Style | Storyteller, digressive | Dense, analytical, objective | Engaging, ethical, anecdotal |

Export to Sheets

In essence, Herodotus created history as a genre, Thucydides refined it into a rigorous analytical discipline, and Plutarch used historical figures primarily as subjects for biography and moral reflection. All three were foundational Western literature and thought figures, but their aims and methods differed significantly.

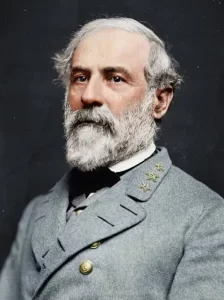

Herodotus

This is a Roman copy (2nd century AD) of a Greek bust of Herodotus from the first half of the 4th century BC.

(Wiki Image By This file was donated to Wikimedia Commons as part of a project by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. See the Image and Data Resources Open Access Policy, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=115708819)

Herodotus Quotes

Herodotus, often called the “Father of History,” filled his work The Histories with observations, stories, and reflections. While attributing precise, concise quotes can sometimes be tricky with ancient translations, here are some key and widely cited statements attributed to him or directly reflecting the sentiments and approach found in his work:

- “Herodotus of Halicarnassus here displays his inquiry, so that human achievements may not be forgotten in time, and great and marvellous deeds – some displayed by Greeks, some by barbarians – may not be without their glory; and especially to show why the two peoples fought with each other.”

- Source: Opening lines of The Histories.

- Significance: This is Herodotus’s mission statement. It clearly outlines his purpose: to preserve the memory of significant events (“human achievements,” “great and marvellous deeds”), to give credit to both Greeks and non-Greeks (“barbarians”), and, crucially, to investigate the causes (“why the two peoples fought”) of the Greco-Persian Wars. This focus on causation is key to why he’s considered the first true historian.

- “My business is to record what people say, but I am by no means bound to believe it – and that may be taken to apply to this book as a whole.”

- Source: The Histories, Book 7.

- Significance: This famous quote reveals Herodotus’s historical method (historia meaning inquiry). He acknowledges that he includes accounts and stories he has heard (oral tradition was a primary source). Still, he maintains a critical distance, indicating that recording something doesn’t equate to personal belief in its absolute truth. It shows an awareness of source reliability, even if his standards differ from modern ones.

- “Custom is king of all.” (Nomos Panton Basileus)

- Source: Often attributed to Herodotus (and the poet Pindar), reflecting a story he tells in The Histories (Book 3) about King Darius comparing Greek and Callatian funeral practices.

- Significance: This encapsulates Herodotus’s keen observation of cultural relativism. Through his travels and inquiries, he recognized that different peoples have vastly different customs and beliefs, each considering their way to be correct. It highlights his ethnographic interest.

- “Circumstances rule men; men do not rule circumstances.”

- Source: Attributed.

- Significance: This reflects a recurring theme in The Histories concerning the role of fate, fortune, and factors beyond individual control in shaping human events. While he focused on human actions, Herodotus often acknowledged that outcomes weren’t solely determined by human will.

- “In peace, sons bury their fathers. In war, fathers bury their sons.”

- Source: The Histories, Book 1 (attributed to Croesus).

- Significance: A poignant reflection on the unnatural tragedy and disruption caused by war, reversing the natural order of life and death. It shows Herodotus’s capacity for conveying the human cost of conflict.

- “It is better to be envied than pitied.”

- Source: The Histories, Book 3.

- Significance: A pragmatic observation on human nature and social standing, typical of the worldly wisdom woven into his narrative.

- “Great deeds are usually wrought at great risks.”

- Source: The Histories, Book 7.

- Significance: Reflects the theme of ambition, risk-taking, and the often perilous path to achieving significant accomplishments, a common motif in the stories of the leaders he describes.

These quotes illustrate Herodotus’s groundbreaking approach: his desire to preserve memory, investigate causes, record diverse perspectives (while maintaining some skepticism), explore different cultures, and reflect on the nature of human fortune and conflict.

Herodotus YouTube Video

- Why is Herodotus called “The Father of History”? – Mark Robinson by TED-Ed: 2,494,104 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A542ixwyBhc)

- History-Makers: Herodotus by Overly Sarcastic Productions: 777,961 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0vRlyPH6REM)

- Herodotus’ Histories (FULL Audiobook) – book (1 of 3) by Audio Books: 316,137 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=doqHoFpRDfY)

- Tom Holland on Herodotus’ Histories by Hay Festival: 163,632 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AHTokb35nGM)

- 330. Herodotus: The Birth of History by The Rest Is History: 31,862 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v7l3Q11DBq0)

Herodotus YouTube Video Movies

The 300 Spartans

(Wiki Image By 20th Century Fox – Impawards, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13104524)

The 300 Spartans (1962) Trailer

300: The portrayal of King Xerxes (right) was criticized. Snyder said of Xerxes, “What’s more scary to a 20-year-old boy than a giant god-king who wants to have his way with you?”

(Wiki Image Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20116456)

300 – Original Theatrical Trailer

300: Rise of an Empire

(Wiki Image By http://www.comingsoon.net/news/movienews.php?id=103085, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39134539)

300: Rise of an Empire – Official Trailer 1 [HD]

Herodotus Books

The single great work of the ancient Greek writer Herodotus is his masterpiece, “The Histories”.

Often called “The Father of History,” Herodotus is renowned for his monumental work, which is the founding text of the historical discipline in Western literature.

The Histories 📜

Written in the 5th century BCE, The Histories is a grand, sprawling account of the Greco-Persian Wars (499–479 BCE), in which the Greek city-states, led by Athens and Sparta, fought to repel two massive invasions by the Persian Empire.

However, the book is much more than just a military history. To explain the causes of the war, Herodotus undertakes a comprehensive exploration of the entire known world. He details the history, culture, geography, and customs of the different peoples of the Persian Empire and beyond, including the Egyptians, Scythians, and Babylonians.

Unlike the purely analytical Thucydides who came after him, Herodotus’s work is a masterful piece of storytelling, filled with fascinating digressions, legends, and ethnographic details. It’s an epic inquiry into the clash of civilizations and the nature of freedom and empire.

Recommended Translations:

- For the most modern and readable translation: “The Landmark Herodotus,” edited by Robert B. Strassler. Like The Landmark Thucydides, this edition is the best choice for a modern reader. It features an excellent translation, extensive maps, and helpful annotations that bring the ancient world to life.

- For a lively, contemporary translation, The Penguin Classics edition, translated by Tom Holland, is also highly acclaimed for its energetic and engaging prose.

Herodotus History

Herodotus (c. 484 – c. 425 BC) is widely regarded as the “Father of History” in Western literature. He was an ancient Greek writer, geographer, and historian who was the first to systematically collect his materials, test their accuracy to a certain extent, and arrange them in a well-constructed and vivid narrative.

- Life and Travels:

- Origin: Born in Halicarnassus, a Greek city in Ionia (modern-day Bodrum, Turkey), part of the Persian Empire. This position at the crossroads of Greek and non-Greek cultures likely influenced his broad perspective.

- Family and Background: He likely came from a relatively wealthy and influential family, which would have facilitated his extensive education and travels.

- Exile: Political troubles in Halicarnassus may have led to his exile for a period.

- Extensive Travels: Herodotus traveled widely throughout the ancient world, a crucial part of his historical method. His known or likely destinations included:

- Egypt (where he traveled extensively along the Nile)

- The Persian Empire (including Mesopotamia)

- Scythia (the region north of the Black Sea)

- Various parts of Greece and the Aegean islands

- Possibly southern Italy (Magna Graecia)

- Later Life: He seems to have spent time in Athens during its Golden Age under Pericles and may have settled in Thurii, a Greek colony in southern Italy, where he likely completed his major work.

- The Histories:

- Significant Work: Herodotus’s single, monumental work is The Histories.

- Scope: While its central theme is the Greco-Persian Wars (499-479 BC), The Histories has a much broader scope. It delves into the origins and rise of the Persian Empire, providing detailed accounts of the geography, ethnography (customs and cultures), and history of the various peoples within the empire and its neighboring regions (including Egyptians, Scythians, Libyans, etc.).

- Purpose: Herodotus states his purpose explicitly in the opening lines:

“Herodotus of Halicarnassus here displays his inquiry, so that human achievements may not be forgotten in time, and great and marvellous deeds – some displayed by Greeks, some by barbarians – may not be without their glory; and especially to show why the two peoples fought with each other.”- This highlights his goals: preserving memory, celebrating great deeds (of both sides), and, crucially, investigating the causes of conflict.

- Methodology and Style:

- Historia (Inquiry): Herodotus approached his work as a historian, which means “inquiry” or “investigation.” He actively sought out information.

- Sources: He relied on a variety of sources:

- Oral Accounts: Interviews with witnesses, priests, local officials, and storytellers encountered during his travels.

- Written Records: Logographers (earlier Greek prose writers), inscriptions, archives (though access was limited).

- Personal Observation: Descriptions of places, monuments, and customs he witnessed.

- Inclusivity: Unlike later historians like Thucydides, Herodotus included many materials, including myths, legends, anecdotes, oracles, and divine interventions alongside political and military narratives.

- Critical Assessment (Limited): He sometimes expressed skepticism about specific stories or presented multiple versions of an event, indicating an essential degree of assessment (e.g., “My business is to record what people say, but I am by no means bound to believe it”). However, his standards for evidence differ significantly from modern historical practice.

- Narrative Style: His writing is engaging, often like a skilled storyteller. He frequently includes digressions and fascinating details about different cultures.

- Criticisms and Reliability:

- “Father of Lies”? Herodotus has been criticized since antiquity (notably by Thucydides and later Plutarch) for including fantastical stories, hearsay, and potential inaccuracies. He was sometimes labelled the “Father of Lies.”

- Bias: While aiming to record the deeds of Greeks and barbarians, his perspective is ultimately Greek.

- Modern Assessment: Modern historians recognize the limitations of his methodology but also value his work immensely. He preserved vast information about the ancient world that would otherwise be lost. His ethnographic descriptions are invaluable, and his attempt to write a comprehensive history focused on causation was groundbreaking.

- Legacy:

- Founder of History: He is credited with establishing history as a distinct literary genre and field of inquiry in the Western tradition.

- Influence: His work influenced subsequent Greek and Roman historians, though some (like Thucydides) consciously reacted against his inclusive, less rigorously analytical style.

- Primary Source: The Histories remains a primary source for the Greco-Persian Wars and for understanding the ancient Near East, Egypt, and Scythia cultures from a Greek perspective.

- Enduring Appeal: His engaging narrative style and wide-ranging curiosity make his work readable and fascinating today.

In summary, Herodotus was a pioneering figure who traveled extensively to gather information for his groundbreaking work, The Histories. While his methods differ from modern standards, his attempt to systematically inquire into the past, explain the causes of significant events like the Greco-Persian Wars, and preserve the memory of diverse peoples earned him the enduring title “Father of History.” His work remains a cornerstone of classical literature and a vital source for understanding the ancient world.

The History of Herodotus

Herodotus: The First Book, Entitled Clio

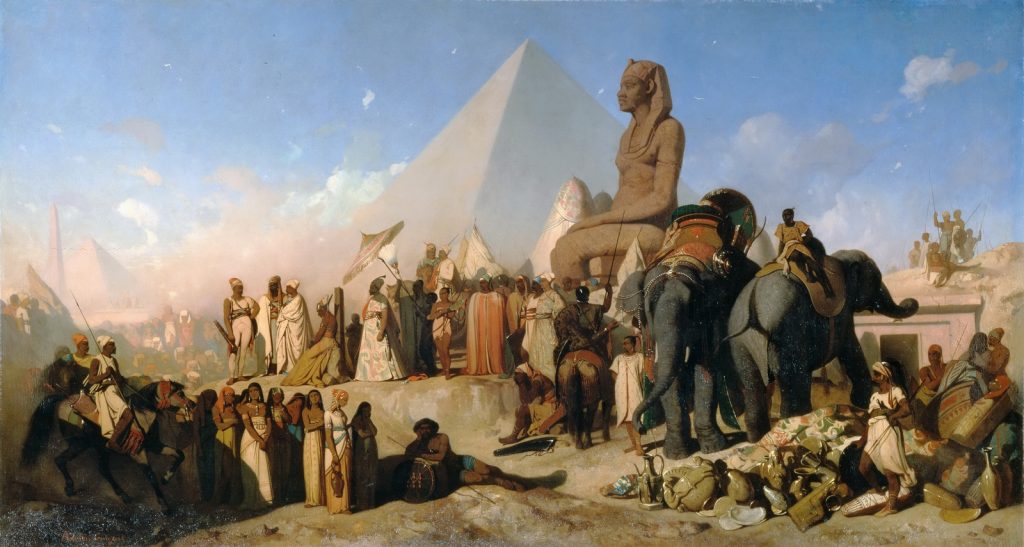

Cyrus the Great (center) with his General Harpagus behind him, as he receives the submission of Astyages (18th century tapestry)

(Wiki Image By Designed by Maximilien de Haese, Woven by Jac. Van der Borght (1771-1775) – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75000688)

Croesus on the pyre, Attic red-figure amphora, 500–490 BC, Louvre (G 197)

(Wiki Image By Myson – User:Bibi Saint-Pol, own work, 2007-06-06, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2228570)

Herodotus Clio Quotes

Here are some significant quotes from Book 1 (Clio) of Herodotus’s The Histories. Keep in mind that translations can vary slightly.

- “Herodotus of Halicarnassus here displays his inquiry, so that human achievements may not be forgotten in time, and great and marvellous deeds – some displayed by Greeks, some by barbarians – may not be without their glory; and especially to show why the two peoples fought with each other.”

- Source: Book 1, Section 1 (Opening lines)

- Context: Herodotus’s preface, stating his purpose for writing.

- Significance: Establishes history to preserve memory, acknowledges non-Greeks’ achievements (“barbarians”), and sets out his primary goal: investigating the causes of the Greco-Persian Wars.

- “Count no man happy until he be dead.” (Often paraphrased this way). The fuller context is Solon speaking to Croesus: “…look to the end of every matter, how it will turn out. For the deity has given prosperous fortune to many and then utterly ruined them.”

- Source: Book 1, Section 32

- Context: The Athenian sage Solon responds to King Croesus of Lydia, who believes himself the happiest man alive due to his immense wealth.

- Significance: This chapter introduces a key theme of the book (and The Histories): the instability of human fortune, the dangers of hubris, and the idea that true happiness or fortune can only be judged over a lifetime. It foreshadows Croesus’s eventual downfall.

- “[The Oracle at Delphi told Croesus:] that if he should send an army against the Persians he would destroy a great empire.”

- Source: Book 1, Section 53

- Context: The famously ambiguous prophecy given to Croesus when he inquired about attacking Cyrus the Great.

- Significance: Illustrates the theme of fate and the often misleading nature of oracles. Croesus tragically misinterpreted this to mean he would destroy the Persian empire, not his own.

- “[Croesus, captured and placed on the pyre by Cyrus, remembered Solon’s words and] groaned and thrice cried out the name ‘Solon!'”

- Source: Book 1, Section 86

- Context: Croesus, facing imminent death on the funeral pyre after his defeat, finally understands the wisdom of Solon’s earlier warning about fortune.

- Significance: A dramatic culmination of the Croesus narrative, emphasizing the themes of hubris, the reversal of fortune, and the wisdom gained through suffering.

- “In peace, sons bury their fathers. In war, fathers bury their sons.”

- Source: Book 1, Section 87

- Context: Croesus spoke to Cyrus after his capture, reflecting on the unnatural tragedy of war.

- Significance: A powerful and timeless observation on the human cost of conflict, highlighting the disruption of the natural order caused by warfare.

- “Soft lands breed soft men.” (Often paraphrased; the context relates to Cyrus advising the Persians against migrating from their rugged homeland to a more prosperous, easier land after their conquests).

- Source: Book 1, Section 157 (This idea is revisited more famously at the end of Book 9, but the core sentiment appears earlier).

- Context: This reflects a common Greek belief about the influence of geography and environment on character.

- Significance: It suggests that hardship breeds strength, while luxury leads to weakness—a theme relevant to empires’ rise and potential fall.

These quotes from Book 1 (Clio) showcase Herodotus’s narrative style, his interest in causation, his use of dialogue and anecdote, and the key themes of fortune, fate, hubris, cultural differences, and the origins of conflict that he establishes at the outset of his great work.

Herodotus Clio Table

Here is a table summarizing the key sections, figures, content, and themes of Herodotus’s Book 1, Clio.

| Section / Major Topic | Key Figures / Peoples Involved | Summary of Content / Key Events | Key Themes / Significance |

| 1. Preface & Introduction | Herodotus himself | States his purpose: to preserve memory, record great deeds (Greek & barbarian), and explain the causes of the Greco-Persian Wars. | Establishes history as inquiry (historia). Sets out the scope and goal of the entire work. |

| 2. Mythical Origins | Io, Europa, Medea, Helen, Paris, Phoenicians, Greeks, Trojans | Recounts legendary abductions and conflicts between East (Asia) and West (Europe) as perceived early causes of animosity. Quickly shift focus to identifiable historical aggressors. | Sets a broad context of ancient East-West conflict and acknowledges traditional myths before moving to historical accounts. |

| 3. Rise of Lydia | Gyges, Candaules, Alyattes, Croesus, Lydians | This is the story of Gyges usurping the throne, establishing and growing the Lydian kingdom, consolidating power, and early interactions with Greek cities. | Lydia is introduced as the first significant non-Greek power to subjugate Ionian Greeks, setting the stage for the central figure of Croesus. |

| 4. Reign of Croesus | Croesus, Solon, Oracle at Delphi, Adrastus, Cyrus the Great, Lydians | Croesus’s immense wealth and power; famous dialogue with Solon on happiness; consultation of oracles (ambiguous prophecy); decision to attack Persia; defeat by Cyrus; capture of Sardis; dramatic scene on the funeral pyre. | This major narrative arc illustrates themes of hubris, instability of fortune, limitations of wealth, misinterpretation of divine signs, and the rise of Persia. Croesus serves as a pivotal, tragic figure. |

| 5. Rise of Persia & Cyrus the Great | Cyrus the Great, Astyages, Medes, Persians, Harpagus | The legendary birth story of Cyrus tells of his upbringing and his successful rebellion against and overthrow of the Median Empire led by his grandfather, Astyages. | Explains the origins and founding of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, the dominant power that would eventually confront Greece. |

| 6. Cyrus’s Conquests | Cyrus, Croesus, Lydians, Ionian Greeks, Babylonians, Massagetae | Conquest of Lydia (defeating Croesus); subjugation of the Ionian Greek cities on the coast of Anatolia; campaigns against other peoples (brief mention of Babylon); final campaign against the Massagetae. | This chapter details the rapid expansion of the Persian Empire under its founder and highlights the Greeks’ subjugation, a key cause of later conflict. |

| 7. Persian Customs | Persians | Ethnographic description of Persian society, religion (Zoroastrian elements mentioned), burial practices, social hierarchy, attitudes towards truth, debt, wine, etc. | It demonstrates Herodotus’ ethnographic interest and provides valuable (though potentially biased) insights into Persian culture from a Greek perspective. |

| 8. Death of Cyrus | Cyrus, Queen Tomyris, Massagetae | Cyrus’s campaign against the nomadic Massagetae, his initial success through trickery, his eventual defeat and death in battle at the hands of Queen Tomyris (according to one tradition reported by Herodotus). | This book concludes the story of the founder of the Persian Empire. It reinforces themes of the limits of power, the unpredictability of fortune, and the dangers of hubris, even for the greatest conquerors. |

Export to Sheets

This table provides a structured overview of the main components of Clio, highlighting the intertwined stories of Lydia and Persia, the key figures of Croesus and Cyrus, and the foundational themes Herodotus establishes for his larger work on the Greco-Persian Wars.

Herodotus Clio Highlights

Okay, here are the significant highlights of Herodotus’s Book 1, Clio:

- Herodotus’s Introduction and Purpose: The book famously opens with Herodotus stating his groundbreaking intention: to conduct an inquiry (historia) to preserve the memory of great deeds by both Greeks and non-Greeks (“barbarians”) and, crucially, to explain the causes of the conflict between them, particularly the Greco-Persian Wars. This sets the stage for history as an analytical discipline.

- The Story of Croesus: This is arguably the most famous narrative arc in Book 1. It details the immense wealth and power of Croesus, King of Lydia, his dialogue with the wise Solon about the nature of happiness (where Solon warns him to “count no man happy until he be dead”), his misinterpretation of the ambiguous Oracle at Delphi, his hubristic attack on Persia, his dramatic defeat by Cyrus the Great, and his near-execution on a pyre (where he is saved after recalling Solon’s wisdom). It’s a powerful cautionary tale about fortune and pride.

- The Rise of Cyrus the Great and Persia: Herodotus chronicles the emergence of the Persian Empire under its founder, Cyrus. This includes the legendary tales of Cyrus’s birth and upbringing, his overthrow of the Median Empire, and his subsequent rapid conquests, including Lydia and the Greek cities of Ionia. This established Persia as the dominant power in the region.

- Ethnographic Descriptions: Clio showcases Herodotus’s keen interest in different cultures. He describes the Lydians’ customs, geography, religion, and social practices, especially the Persians. While containing potential inaccuracies and Greek biases, these sections are invaluable for understanding ancient perceptions and preserving cultural details.

- Introduction of Key Themes: This first book introduces significant themes that resonate throughout The Histories:

- The instability of human fortune (the rise and fall of individuals and empires).

- The dangers of hubris (excessive pride leading to downfall, exemplified by Croesus).

- The clash between cultures (East vs. West, Greek vs. Barbarian).

- The role of fate, oracles, and divine intervention alongside human actions.

- The investigation of causation in historical events.

- The “First Wrongs”: Herodotus identifies Croesus as the first non-Greek ruler (from his perspective) to commit injustices against the Greeks by conquering the Ionian cities, setting a historical precedent for the later Persian conflict.

In essence, Book 1 (Clio) serves as a rich foundation, introducing the main antagonist (Persia), exploring the historical background through Lydia’s lens, and establishing the key themes and narrative style that define Herodotus’s entire work.

Herodotus: The Second Book, Entitled Euterpe

The Great Pyramid in May 2023

(WIki Image By Douwe C. van der Zee – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=138278511)

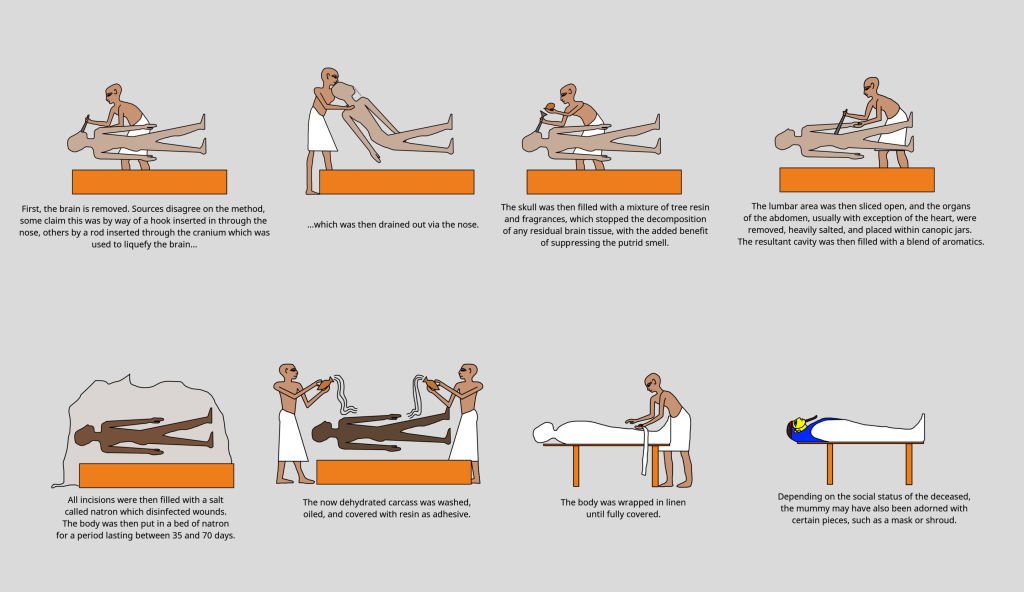

Simplistic representation of the Ancient Egyptian mummification process.

(Wiki Image By SimplisticReps – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=92280695)

Herodotus Euterpe Quotes

Here are some notable quotes and representative statements from Herodotus’s Book 2, Euterpe, which is dedicated entirely to his descriptions and inquiries about Egypt. This book is famous for its detailed (though not consistently accurate) accounts of Egyptian geography, history, customs, and religion.

- “Egypt… is an acquired country, the gift of the river.”

- Source: Book 2, Section 5

- Context: Herodotus describes Egypt’s geography and the Nile River’s crucial role in creating fertile land through its annual floods and silt deposits.

- Significance: This is perhaps the most famous quote about Egypt attributed to Herodotus (though he might have been quoting Hecataeus). It encapsulates the Nile’s fundamental importance to Egyptian civilization.

- “Concerning Egypt, I shall extend my remarks to a great length because there is no country that possesses so many wonders nor any that has such a number of works which defy description.”

- Source: Book 2, Section 35

- Context: Introducing his detailed discussion of Egyptian customs.

- Significance: This shows Herodotus’s profound fascination and awe with Egypt’s unique culture, ancient history, and monumental architecture. It sets the stage for his detailed ethnographic descriptions.

- “…the people also, in most of their manners and customs, exactly reverse the common practice of mankind.”

- Source: Book 2, Section 35

- Context: Following the quote above, Herodotus begins listing examples where he perceives Egyptian customs as the opposite of Greek (or other) practices (e.g., women attending market, men weaving at home, writing from right to left).

- Significance: This passage highlights Herodotus’s ethnographic approach and tendency to emphasize the “otherness” or unique aspects of foreign cultures, particularly Egypt, which deeply impressed Greek visitors.

- “The Egyptians are religious to excess, far beyond any other race of men.”

- Source: Book 2, Section 37

- Context: Introducing his discussion of Egyptian religious practices.

- Significance: This document reflects the Greek perception of the Egyptians as deeply pious and their religious life as pervasive and elaborate, particularly noting practices like meticulous cleanliness and animal worship.

- “[Regarding the builders of the pyramids, like Cheops:] he closed all the temples and forbade the Egyptians to offer sacrifice, compelling them instead to labour, one and all, in his service.”

- Source: Book 2, Section 124

- Context: Recounting stories he heard from priests about the pharaohs responsible for building the Great Pyramids.

- Significance: This document illustrates Herodotus’s method of reporting historical traditions (often critical of powerful rulers) as told to him by his sources (in this case, Egyptian priests). It shows his interest in the history and reigns of the pharaohs, even if the accounts mix fact and legend.

- “As to the stories that I was told by the priests concerning the gods, I am not desirous of repeating them, saving only the names…”

- Source: Book 2, Section 3

- Context: Expressing caution about relating certain Egyptian religious myths or secret doctrines.

- Significance: This shows a degree of respectful reticence or skepticism about revealing sacred or potentially unbelievable religious details, contrasting with his willingness to report other wonders.

- “[The crocodile] during the four winter months… eats nothing; it is amphibious, and lives mainly in the river, but also frequents the land and marshy ground…”

- Source: Book 2, Section 68

- Context: Part of his detailed descriptions of Egyptian wildlife.

- Significance: Demonstrates his keen interest in natural history and his practice of recording details about the flora and fauna of the lands he visited, blending geography, zoology, and ethnography.

These quotes from Book 2 (Euterpe) showcase Herodotus’s fascination with Egypt, his ethnographic curiosity, his method of reporting what he saw and heard (from priests and others), his interest in geography and natural history, and his tendency to highlight the unique and wondrous aspects of Egyptian civilization as perceived through Greek eyes.

Herodotus Euterpe Table

Okay, here is a table summarizing the key aspects, content, and themes of Herodotus’s Book 2, Euterpe, which focuses entirely on Egypt.

| Major Topic / Category | Key Subjects Covered / Examples | Herodotus’s Approach / Key Observations or Claims | Significance / Themes Introduced |

| Geography | – The Nile River: Its unique nature, annual flood, attempts to understand its source (acknowledges uncertainty), crucial role in creating fertile land. <br> – The land of Egypt: Described as the “gift of the river.” | – Observation, inquiry, reporting local explanations (often mythical) for the flood. <br> – Expresses wonder at the Nile’s behavior. | – Emphasizes the centrality of the Nile to Egyptian life and civilization. <br> – Highlights geographical wonders and the limits of Greek knowledge (Nile’s source). |

| History | – Lists of Pharaohs: From Menes (first king) through various dynasties, including builders like Cheops (Khufu), Chephren (Khafre), Mycerinus (Menkaure), and conquerors like Sesostris. <br> – Stories about their reigns: Often anecdotal, focusing on monumental building, laws, piety, or tyranny. | – Relies heavily on accounts heard from Egyptian priests and local informants. <br> – Mixes historical figures with legendary deeds and potentially inaccurate chronologies. <br> – Records traditions about the pharaohs. | – Preserves Egyptian historical traditions (as understood/related by his sources). <br> – Explores themes of kingship, power, piety vs. tyranny (e.g., contrasting Mycerinus with Cheops). <br> – Accuracy is highly variable. |

| Religion | – Egyptian Gods: Describes the pantheon, often equating Egyptian gods with their Greek counterparts (e.g., Amun = Zeus, Osiris = Dionysus, Isis = Demeter). <br> – Animal Worship: Detailed accounts of the veneration of sacred animals (cats, crocodiles, bulls like Apis, ibis). <br> – Rituals and Practices: Describes elaborate religious rituals, festivals, oracles, and beliefs about purity. <br> – Mummification: Provides a detailed (though not entirely accurate) description of embalming techniques. <br> – Afterlife Beliefs: Discusses beliefs about the soul’s immortality and transmigration. | – Detailed descriptions based on observation and priestly accounts. <br> – Expresses awe at Egyptian piety (“religious to excess”). <br> – Sometimes cautious about revealing sacred mysteries. <br> – Attempts interpretatio Graeca (explaining foreign gods in Greek terms). | – Provides invaluable (though potentially filtered or misunderstood) information on Egyptian religious beliefs and practices. <br> – Highlights Egyptian influence on Greek religion. <br> – Explores piety, death, and the afterlife themes. |

| Customs and Society | – Daily Life: Describes aspects of diet, clothing, and medicine. <br> – “Reversal” of Customs: Famously claims many Egyptian customs are the opposite of Greek practices (e.g., women in markets, men weaving at home, specific hygiene rules). <br> – Writing: Describes hieroglyphic and demotic scripts. <br> – Social Hierarchy: Implicit descriptions of priests, soldiers, artisans, etc. | – Observation and comparison with Greek customs, often emphasizing Egyptian uniqueness and perceived “otherness.” <br> – Relies on local informants. | – Rich ethnographic detail, offering a window into Egyptian society (as seen by a Greek). <br> – Explores themes of cultural difference and relativism. <br> – The “reversal” theme is a famous, though perhaps exaggerated, aspect of his account. |

| Natural History | – Animals: Descriptions of crocodiles, hippopotamuses, ibis, snakes, and the mythical phoenix. <br> – Plants: Discusses papyrus and other flora. | – Observing and reporting local stories and beliefs about animals (mixing factual description with folklore). | – Herodotus’s broad curiosity extends beyond human affairs to the natural world. <br> – Provides early examples of natural history writing. |

| Architecture | – Pyramids: Describe their construction (attributing them to tyrannical pharaohs like Cheops). <br> – Temples: Mention major temple complexes (e.g., Karnak, Memphis). <br> – The Labyrinth: Describes a vast, complex funerary temple near Lake Moeris. | – Descriptions based on observation and local accounts. <br> – Expresses wonder and amazement at the scale, antiquity, and engineering skill involved in Egyptian monuments. | – Records Greek impressions of Egypt’s monumental architecture. <br> – Contributes to the Greek (and later European) awe of ancient Egyptian civilization. |

Export to Sheets

This table summarizes the rich and diverse content of Herodotus’s Book 2, Euterpe. It highlights his deep fascination with Egypt, his methods of gathering information (travel, interviews, observation), and the recurring themes of cultural comparison, religious piety, the importance of the Nile, and the wonders of Egypt’s ancient history and monuments. It also implicitly shows his work’s blend of factual reporting, received tradition, and legend.

Herodotus Euterpe Highlights

Here are the significant highlights of Herodotus’s Book 2, Euterpe, his extensive account of Egypt:

- Egypt as the “Gift of the Nile”: Herodotus famously describes Egypt as the creation of the Nile River, emphasizing the vital importance of its annual flood and silt deposits for the land’s fertility and the civilization’s survival. He marvels at the river’s unique behavior and inquires (ultimately unsuccessfully) into the mystery of its source.

- Antiquity and Wonders: Throughout the book, Herodotus expresses profound awe at the sheer age of Egyptian civilization and its “wonders,” which he considers more numerous than any other country. This sense of ancientness and magnificence permeates his descriptions.

- “Reversed” Customs: A memorable section details numerous Egyptian customs and manners that Herodotus claims are the opposite of Greek (and general human) practices, such as women attending market while men weave at home, specific hygiene rituals, and their unique writing system. This highlights his ethnographic interest and emphasis on cultural differences.

- Deep Religious Piety and Practices: He extensively covers Egyptian religion, describing the Egyptians as “religious to excess.” Highlights include:

- Detailed accounts of various gods (often equated with Greek deities).

- Vivid descriptions of animal worship (cats, crocodiles, Apis bull).

- Elaborate religious festivals and rituals.

- Fascinating details about divination and oracles.

- A famous, detailed description of different methods of mummification.

- Monumental Architecture (Especially Pyramids): Herodotus provides early descriptions of Egypt’s incredible monuments, most notably the Pyramids of Giza. He recounts stories (likely blending fact and legend learned from priests) about the pharaohs who built them, such as Cheops (Khufu), often portraying them critically as tyrants who enslaved their people for these projects. He also describes the vast Labyrinth complex.

- Natural History: His curiosity extends to the natural world, and he offers descriptions of Egyptian animals like crocodiles (with details on their habits and how they were hunted), hippopotamuses, ibises, and the mythical phoenix bird.

- Historical Accounts of Pharaohs: Herodotus’s narratives about various pharaohs rely heavily on priestly accounts and potentially inaccurate chronologies, offering a glimpse into Egyptian history as understood in his time.

Book 2 (Euterpe) is a rich tapestry of geography, history, ethnography, religion, and natural history centered on Herodotus’s fascination with Egypt’s ancient, unique, and wondrous civilization. It showcases his method of inquiry, storytelling ability, and role in transmitting knowledge (and sometimes myths) about Egypt to the Greek world.

Herodotus: The Third Book, Entitled Thalia

Imaginary 19th-century illustration of Cambyses II meeting Psamtik III.

(Wiki Image By Adrien Guignet – http://www.the-athenaeum.org/art/detail.php?ID=108972&msg=You+were+sent+here+because+this+artist+only+has+one+artwork+in+our+database.++This+is+it., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30405983)

The relief stone of Darius the Great in the Behistun Inscription

(Wiki Image By Rumlu – [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=146053444)

Herodotus Thalia Quotes

Here are some significant quotes and representative statements from Herodotus’s Book 3, Thalia. This book focuses primarily on the reign of the Persian King Cambyses II (son of Cyrus), his conquest of Egypt, his alleged madness, the subsequent revolt of the Magi, and the rise of Darius the Great.

- “[Amasis wrote to Polycrates of Samos:] ‘Your exceeding good fortune does not please me, as I know the divinity is jealous. […] Toss away that thing… which, if you lost it, would grieve your soul the most.'”

- Source: Book 3, Section 40

- Context: The Egyptian Pharaoh Amasis advises his ally Polycrates, the extremely lucky tyrant of Samos, to deliberately discard his most valued possession (an emerald ring) to avert divine jealousy and potential disaster. Polycrates throws the ring into the sea, only for it to be found inside a fish presented to him later – suggesting his fortune is inescapable.

- Significance: This chapter introduces the story of Polycrates, a classic example in Herodotus of the theme of hubris and the instability of excessive good fortune, which often attracts divine envy (nemesis).

- “[Otanes argued for democracy:] ‘My opinion is… that we must entrust the government to the whole body of the people… For the rule of the many, in the first place, has the fairest of names, equality before the law (isonomia)…'” (Paraphrased for clarity)

- Source: Book 3, Section 80

- Context: This is part of the famous (and likely fictionalized or anachronistic) debate among the seven Persian conspirators after they overthrew the Magi usurper. Otanes advocates for establishing a democracy in Persia.

- Significance: It presents one of the earliest recorded arguments for democracy, highlighting its perceived fairness and accountability, as a Greek writer understands.

- “[Megabyzus argued for oligarchy:] ‘Nothing is more foolish or more insolent than a useless mob… let us choose a group of the best men, and entrust the government to them…'” (Paraphrased for clarity)

- Source: Book 3, Section 81

- Context: Megabyzus responds to Otanes during the debate, arguing against democracy and in favor of rule by an elite group (oligarchy).

- Significance: It presents the oligarchic argument against mob rule’s perceived instability and ignorance.

- “[Darius argued for monarchy:] ‘Nothing can be found better than the rule of the one best man. His judgment being wise as himself, he will govern the multitude with discretion… In an oligarchy… strong personal enmities commonly arise… In a democracy, it is impossible but that there will be corruption…'” (Paraphrased for clarity)

- Source: Book 3, Section 82

- Context: Darius delivers the winning argument in the debate, advocating for monarchy as the most stable and effective form of government.

- Significance: This section presents the case for monarchy, emphasizing efficiency and wisdom under a single, capable ruler. It provides valuable insight into Greek political thought (ascribed to Persians).

- “[On Cambyses’ madness:] For it is plain to all men that he was completely mad; otherwise he would not have set himself to deride religion and custom.”

- Source: Book 3, Section 38

- Context: Herodotus concludes a section detailing Cambyses’s alleged outrages against Egyptian religious practices (like killing the sacred Apis bull) and Persian customs.

- Significance: This shows Herodotus attributing Cambyses’s tyrannical actions to madness, which is often linked in Greek thought to impiety and disrespect for customs (both one’s own and others’). It serves as a negative example of kingship.

- “[On Darius becoming king through his horse neighing:] Darius’s groom… contrived a trick… [when the horses were brought out] Darius’s horse ran forward and neighed, and at the same time lightning flashed from a clear sky… the other six leaped from their horses and prostrated themselves before Darius.” (Paraphrased narrative summary)

- Source: Book 3, Sections 85-87

- Context: The story of how Darius won the kingship after the conspirators agreed that he whose horse neighed first at sunrise would be king.

- Significance: A famous, likely legendary tale illustrating Darius’s cleverness (or his groom’s) and perhaps suggesting divine favor in his rise to power, cementing the legitimacy of his rule after the overthrow of the Magi.

These quotes from Book 3 (Thalia) highlight its key narratives and themes: the dangers of unchecked power and madness (Cambyses), reflections on different forms of government, the precariousness of fortune (Polycrates), and the dramatic rise of Darius the Great to the Persian throne.

Herodotus Thalia Table

Here is a table summarizing the key sections, figures, content, and themes of Herodotus’s Book 3, Thalia. This book primarily covers the reign of Persian King Cambyses II and the rise of Darius the Great.

| Section / Major Topic | Key Figures / Peoples Involved | Summary of Content / Key Events | Key Themes / Significance |

| 1. Cambyses’ Invasion of Egypt | Cambyses II, Amasis (deceased Pharaoh), Psammenitus III (new Pharaoh), Persians, Egyptians | Background involving Amasis; Persian invasion; defeat of the Egyptian army at Pelusium; capture of Memphis; capture and initial humiliation, then execution, of Pharaoh Psammenitus III. | The expansion of the Persian Empire into Africa, the demonstration of Persian military power, and the introduction of Cambyses as a successful conqueror (initially). |

| 2. Cambyses’ Madness & Tyranny in Egypt | Cambyses, Apis Bull, Egyptian priests | Cambyses’ alleged increasingly erratic and impious behavior in Egypt: mocking Egyptian customs, wounding and causing the death of the sacred Apis bull, and desecrating temples and tombs. | The portrayal of Cambyses as descending into madness and tyranny, linked to impiety, explores the corrupting influence of absolute power and contrasts with Cyrus’s generally more tolerant rule. |

| 3. Cambyses’ Failed Expeditions | Cambyses, Persians, Ethiopians, Ammonians | Disastrous expedition against Ethiopia (army resorts to cannibalism due to poor planning); mysterious disappearance of an army sent against the Oasis of Ammon (supposedly buried in a sandstorm). | It demonstrates the limits of Persian power and the potential consequences of Cambyses’ hubris and poor judgment, hinting at divine retribution. |

| 4. Cambyses’ Cruelty | Cambyses, Smerdis (Bardiya – his brother), his sister/wife, Prexaspes | Execution of his brother Smerdis out of jealousy, marries and later kills his sister; shooting the son of his trusted advisor Prexaspes through the heart to prove his sanity/skill. | Further evidence of Cambyses’ alleged madness, cruelty, and tyrannical nature highlights the dangers those close to an absolute ruler face. |

| 5. Revolt of the Magi | Cambyses, Patizeithes (Magus), Smerdis the Magus (Gaumata), Persians | While Cambyses is absent, two Magi brothers revolt; one (Gaumata) impersonates the murdered Smerdis and claims the throne, gaining widespread support due to resentment against Cambyses. | It highlights instability within the Persian Empire, uses the theme of deception and false identity, and sets the stage for Darius’s rise. |

| 6. Death of Cambyses | Cambyses | Hears news of the Magi revolt while returning from Egypt, accidentally wounds himself severely with his sword while mounting his horse, and dies from the gangrenous wound, supposedly realizing an oracle about his death. | It ended the reign of the tyrannical king, which Herodotus saw as possible divine retribution. It created a power vacuum and allowed the Magi to consolidate control briefly. |

| 7. Conspiracy of the Seven | Darius, Otanes, Gobryas, Megabyzus, other Persian nobles, Smerdis the Magus | Seven Persian nobles, led by Otanes and Darius, conspire to expose the impersonation and overthrow the false Smerdis (the Magus); they enter the palace and kill the Magi. | It restores Persian control from the Median Magi and demonstrates the power and solidarity of the Persian nobility. |

| 8. Debate on Government | Otanes, Megabyzus, Darius | The famous (possibly anachronistic) debate among the seven conspirators about Persia’s best form of government: Otanes argues for democracy (isonomia), Megabyzus for oligarchy, and Darius successfully argues for monarchy. | This is a unique passage exploring Greek political theory through Persian characters. It presents arguments for different constitutional forms and provides insight into the political thought of Herodotus’s time. |

| 9. Darius Becomes King | Darius, the other six conspirators, Oebares (Darius’s groom) | The agreement that he whose horse neighs first at sunrise shall be king; the clever trick contrived by Darius’s groom involving a mare; Darius’s horse neighs, accompanied by auspicious lightning; Darius wins the throne. | Explains (through a likely legendary account) how Darius ascended to the throne over the other conspirators and legitimizes his rule through perceived divine favor and cleverness. |

| 10. Darius’s Early Reign & Organization | Darius, Persians, Babylonians, Zopyrus | Reorganization of the Persian Empire into satrapies (provinces); establishment of a fixed tribute system; building projects; suppression of the long Revolt of Babylon (including the famous story of Zopyrus mutilating himself to gain the Babylonians’ trust). | It shows Darius as an effective administrator and consolidator of the empire and establishes the structure of the Persian Empire that would confront Greece. |

| 11. Digressions | Polycrates of Samos, Amasis, Oroetes (Persian satrap), Democedes (Greek physician) | This is the story of Polycrates’s excessive good fortune, the advice from Amasis, the discarded ring, and his eventual cruel death at the hands of Oroetes. The story concerns Democedes’s capture, medical service at the Persian court, and eventual escape. | Illustrate themes of fortune’s instability (Polycrates) and the interactions between Greeks and Persians, including Greek skills valued at the Persian court (Democedes). Provides colour and moral lessons. |

Export to Sheets

This table structure follows the primary narrative threads of Herodotus’s Book 3, Thalia, outlining the key events, figures, and underlying themes concerning the reigns of Cambyses and the rise of Darius.

Herodotus Thalia Highlights

Here are the key highlights from Herodotus’s Book 3, Thalia:

- Cambyses’ Conquest of Egypt: The book details the Persian invasion under Cyrus’s son, Cambyses II, leading to the defeat of the Egyptians and the expansion of the Persian Empire into Africa.

- Cambyses’ Madness and Tyranny: A significant portion focuses on Cambyses’ alleged descent into madness following his conquest. Herodotus recounts his impious acts (like killing the sacred Apis bull), cruelty towards his own family (killing his brother Smerdis and sister/wife), fits of rage, and disastrously planned military expeditions (against Ethiopia and the Oasis of Ammon).

- The Revolt of the Magi (The False Smerdis): While Cambyses is away, two Magi brothers revolt. One, Gaumata, impersonates Cambyses’ murdered brother Smerdis and usurps the Persian throne, highlighting instability within the empire.

- The Conspiracy of the Seven: Upon Cambyses’ death (from an accidental wound), seven Persian nobles, including Darius, conspire to expose the imposter and overthrow the Magi usurper, restoring Persian control.

- The Debate on Government: Following the overthrow of the Magi, Herodotus includes a famous (though likely anachronistic) debate among the seven conspirators (Otanes, Megabyzus, and Darius) regarding the best form of government: democracy, oligarchy, or monarchy. Darius’s argument for monarchy ultimately prevails.

- Darius Becomes King: The book recounts the (likely legendary) story of how Darius cleverly ensured his horse neighed first at sunrise, thereby winning the throne according to the conspirators’ agreement.

- Darius Organizes the Empire: This book highlights Darius the Great’s early reign, focusing on his crucial reorganization of the vast Persian Empire into satrapies (provinces) with fixed systems of tribute and administration.

- The Story of Polycrates of Samos: This famous digression tells the story of the extraordinarily fortunate tyrant Polycrates. His attempt to ward off divine jealousy by discarding his most prized possession fails spectacularly, leading to his eventual capture and gruesome death. Thus, the story serves as a powerful cautionary tale about hubris and the instability of fortune.

Herodotus: The Fourth Book, Entitled Melpomene

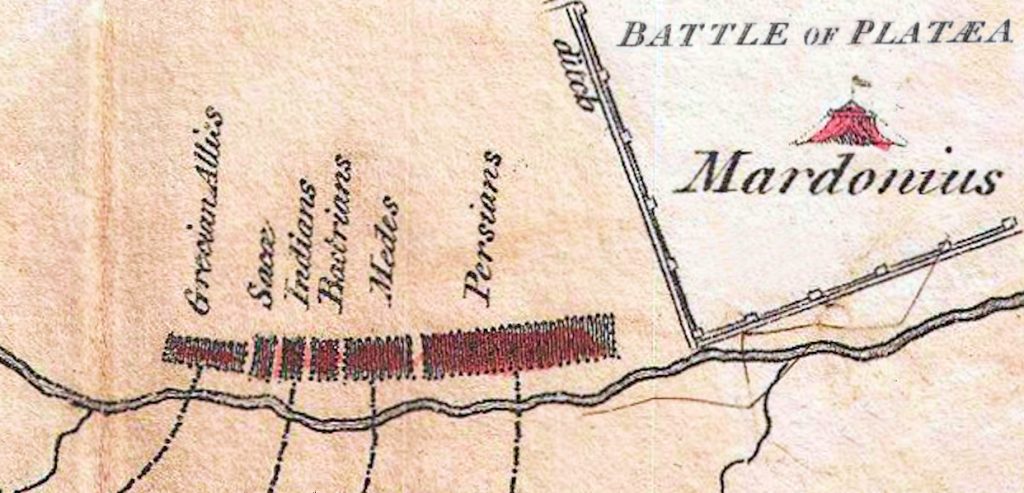

Map of the European Scythian campaign of Darius I

(Wiki Image By anton Gutsunaev, traduction GrandEscogriffe – File:DariusScythes ru.svg, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=101702352)

Reconstructed map of the world based on the writings of Herodotus

(Wikimedia This file is from the Mechanical Curator collection, a set of over 1 million images scanned from out-of-copyright books and released to Flickr Commons by the British Library. View image on FlickrView all images from bookView catalogue entry for book., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37643792)

Herodotus Melpomene Quotes

Here are some significant quotes and representative statements from Herodotus’s Book 4, Melpomene. This book primarily focuses on Darius the Great’s expedition against the Scythians and includes extensive ethnographic descriptions of Scythia and Libya (North Africa).

- “[The Scythians] have planned their affairs… wisely… having neither cities nor forts, and carrying their dwellings with them… accustomed, moreover, one and all, to shoot from horseback; and living not by husbandry but on their cattle, their dwellings being wagons, — how should they not be invincible and impossible to approach?”

- Source: Book 4, Section 46

- Context: Herodotus explains the nature of the Scythian people and their nomadic lifestyle.

- Significance: This quote perfectly captures Herodotus’s understanding of why the Scythians were so tricky for the settled Persian Empire to conquer. Their mobility and lack of fixed targets rendered traditional siege warfare useless, highlighting the clash between nomadic and settled societies.

- “[The Scythian message to Darius, sending gifts of a bird, a mouse, a frog, and five arrows, was interpreted:] ‘Unless you Persians become birds and fly up into the sky, or mice and hide yourself in the earth, or frogs and leap into the lakes, you will never return home, but will be shot by these arrows.'”

- Source: Book 4, Sections 131-132

- Context: The Scythians send symbolic gifts to Darius during his frustrating invasion, which Darius initially misinterprets, but one of his advisors correctly deciphers the defiant message.

- Significance: A famous example of symbolic communication and Scythian defiance. It encapsulates their strategy: They cannot be conquered directly and will wear down the invader.

- “Hitherto the Samians had been ready to obey all the orders of the Persians… But now they thought it a grand thing to save Ionia…”

- Source: Book 4, Section 138

- Context: Describing the debate among the Ionian Greek commanders guarding the bridge over the Danube River during Darius’s retreat from Scythia. Miltiades (later hero of Marathon) urges them to destroy the bridge and trap Darius, but Histiaeus of Miletus persuades them to wait.

- Significance: This crucial moment foreshadows the later Ionian Revolt against Persia. It shows the divided loyalties and emerging resistance among the Greek subjects of Persia.

- “The Scythians… take some of this hemp-seed [cannabis], and, creeping under the felt coverings, throw it upon the red-hot stones; immediately it smokes, and gives out such a vapour as no Grecian vapour-bath can exceed; the Scyths, delighted, shout for joy…”

- Source: Book 4, Section 75

- Context: Part of Herodotus’s detailed description of Scythian customs, specifically their purification rituals after funerals.

- Significance: This is one of the earliest written accounts of inhaling cannabis vapor for ritualistic or recreational purposes. It exemplifies Herodotus’s detailed ethnographic interest.

- “When their king dies, they dig a great square pit… [they bury him with] one of his concubines, strangled, his cup-bearer, his cook, his groom, his lackey, his messenger… horses… and firstlings of all his other possessions…” (Paraphrased summary)

- Source: Book 4, Section 71

- Context: Describe the elaborate and brutal royal burial practices of the Scythians.

- Significance: This is another striking example of Herodotus’s detailed ethnographic reporting. It highlights customs vastly different from Greek practices and provides valuable (though potentially exaggerated) anthropological information.

- “Respecting the regions that lie beyond the countries mentioned, it is impossible to obtain any certain information… No one has any exact knowledge.”

- Source: Book 4, Section 16

- Context: Herodotus is discussing the lands north of Scythia.

- Significance: This passage shows Herodotus acknowledging the limits of his knowledge and inquiry, an essential aspect of his historical method. He distinguishes between what he has heard or seen and what is unknown.

- “Libya is washed on all sides by the sea except where it joins Asia…”

- Source: Book 4, Section 42

- Context: Introducing his section on Libya (North Africa), discussing attempts to circumnavigate it.

- Significance: This sets the stage for his geographical and ethnographical descriptions of North Africa, demonstrating the breadth of his inquiries beyond the immediate Greco-Persian world.

These quotes from Book 4 (Melpomene) illustrate Herodotus’s focus on the Scythian campaign, his fascination with nomadic cultures and exotic lands (Scythia and Libya), his detailed ethnographic descriptions, and the recurring themes of cultural clash and the limits of imperial power.

Herodotus Melpomene Table

Here is a table summarizing the key sections, content, and themes of Herodotus’s Book 4, Melpomene. This book is primarily dedicated to Scythia and Libya (North Africa).

| Major Topic / Section | Key Subjects Covered / Examples | Herodotus’s Approach / Key Observations or Claims | Key Themes / Significance |

| 1. Scythian Geography & Origins | – Geography of Scythia (rivers like Ister/Danube, Borysthenes/Dnieper; vast plains). <br> – Legendary origins of the Scythians (e.g., descendants of Heracles, Targitaus). | – Geographical descriptions based on available accounts. <br> – Reporting of various origin myths without definitively choosing one. | – Sets the physical stage for Darius’s campaign. <br> – Emphasizes the land’s vast, open, and relatively unknown nature. <br> – Inclusion of myth alongside geography. |

| 2. Scythian Ethnography (Customs & Culture) | – Nomadic Lifestyle: Living in wagons and relying on cattle. <br> – Warfare: Skilled mounted archers, retreat strategy, guerrilla tactics. <br> – Religion: Pantheon of gods (often equated with Greek gods), lack of temples/altars. <br> – Rituals: Oaths involving blood, elaborate royal burial practices with human/animal sacrifice. <br> – Unique Customs: Use of cannabis vapor baths, scalping enemies. | – Detailed descriptions based primarily on accounts gathered (from Greeks, possibly Scythians). <br> – Emphasis on customs perceived as unique or different from Greek norms. <br> – Expresses wonder at certain practices. <br> – Observation: “[The Scythians]… how should they not be invincible…?” | – Provides invaluable (though potentially biased or exaggerated) ethnographic information on nomadic cultures. <br> – Highlights the clash between nomadic and settled societies. <br> – Reinforces the idea of Scythian resilience and military effectiveness. |

| 3. Darius’s Scythian Expedition | – Darius’s motivations (revenge, expansion). <br> – Construction of a bridge over the Ister (Danube). <br> – Invasion of Scythia. <br> – Scythian strategy: Scorched earth, constant retreat, avoiding pitched battle, harassing Persians. <br> – Darius’s frustration and pursuit deep into Scythian territory. <br> – Symbolic messages (bird, mouse, frog, arrows). <br> – Debate among Ionian Greeks at the Danube bridge (should they trap Darius?). <br> – Darius’s rugged retreat and escape. | – Narrative history based on available accounts. <br> – Focuses on the clash of military strategies. <br> – Emphasizes the difficulties faced by the large, conventional Persian army against elusive nomads. | – The main historical narrative of Book 4. <br> – Illustrates the limits of Persian imperial power against unconventional enemies and challenging geography. <br> – Explores themes of hubris (Darius) and strategic wisdom (Scythians). <br> – Foreshadows later Greek resistance. |

| 4. Geography of Libya (North Africa) | – Description of the lands west of Egypt. <br> – Coastal regions, interior deserts, different climatic zones. <br> – Discussion of attempts to circumnavigate Africa. | – Geographical descriptions based on accounts gathered, likely less from direct observation than Egypt. <br> – Acknowledges the limits of geographical knowledge. | – Expands Herodotus’s geographical scope to another part of the known world. <br> – Provides information on the Greek understanding of North Africa. |

| 5. Libyan Ethnography | – Descriptions of numerous Libyan tribes (nomadic and settled – e.g., Nasamones, Garamantes, Atlantes, Lotus-eaters). <br> – Their diverse customs, diets, warfare methods. <br> – Descriptions of animals found in Libya. | – Reporting accounts heard about various peoples, sometimes including fantastical elements. <br> – Comparison of customs. | – Continues Herodotus’s ethnographic project. <br> – Preserves information (and Greek perceptions) about North African peoples. |

| 6. Greek Colonization (Cyrene) | – Story of the founding of the Greek colony of Cyrene in Libya, including the role of the Delphic Oracle and the challenges faced by the colonists. | – Narrative based on Greek traditions and stories. | – Explains the Greek presence in North Africa and its origins. |

| 7. Persian Involvement in Libya | – Limited Persian campaigns and interactions in Libya, often linked to events in Egypt or Cyrene (e.g., expedition against Barca). | – Brief historical accounts connecting Libya to the broader Persian Empire narrative. | – Ties the Libyan digression to the Persian power and expansion theme. |

Export to Sheets

This table provides a structured overview of the main components of Herodotus’s Book 4, Melpomene. It highlights the dual focus on Scythia and Libya, the detailed ethnographic descriptions, the central narrative of Darius’s failed Scythian campaign, and the recurring themes of cultural comparison, geography’s influence, and the limits of imperial power. The format allows for a clear understanding of the book’s structure and diverse content.

Herodotus Melpomene Highlights

Here are the significant highlights of Herodotus’s Book 4, Melpomene:

- Darius’s Failed Scythian Expedition: The central historical narrative details the massive Persian invasion of Scythia led by Darius the Great. It chronicles the immense logistical challenges, the frustrating pursuit of an elusive enemy, and the campaign’s ultimate failure, demonstrating the limits of Persian imperial power against nomadic peoples and harsh geography.

- Scythian Nomadic Strategy and Lifestyle: Herodotus provides a compelling explanation for Scythian “invincibility,” focusing on their nomadic lifestyle (living in wagons, lacking fixed cities), their mastery of mounted archery, and their effective military strategy of avoiding pitched battles, employing scorched-earth tactics, and using strategic retreats to exhaust their enemy.

- Rich Scythian Ethnography: The book contains extensive and fascinating (though not always historically verifiable) descriptions of Scythian culture and customs. Highlights include their complex royal burial rituals involving human and animal sacrifice, unique methods of making oaths, reverence for certain gods (often equated with Greek ones), and the famous account of their use of cannabis vapor baths.

- Exploration of Libya (North Africa): Herodotus shifts focus to provide a detailed ethnographic and geographic survey of the peoples inhabiting North Africa west of Egypt. He describes numerous tribes (both nomadic and settled, like the Lotus-eaters), their diverse customs, the region’s climate, and its distinctive wildlife.

- Greek Colonization Narrative: Includes the traditional story of the founding of the important Greek colony of Cyrene in Libya, involving oracles from Delphi and the challenges faced by the early settlers.

- Acknowledging Geographical Limits: Herodotus discusses the geography of the known world, including attempts to understand the course of major rivers and the shape of continents (like the circumnavigation of Africa), while also frankly admitting the limits of knowledge regarding the distant northern regions beyond Scythia.

In essence, Book 4 (Melpomene) stands out for its deep dive into nomadic cultures, particularly the Scythians, contrasting them with the settled Persian Empire. It’s a book about the clash of civilizations, the influence of geography on culture and warfare, and the vast, diverse world known (and unknown) to the Greeks, all woven around the central narrative of Darius’s challenging Scythian campaign.

Herodotus: The Fifth Book, Entitled Terpsichore

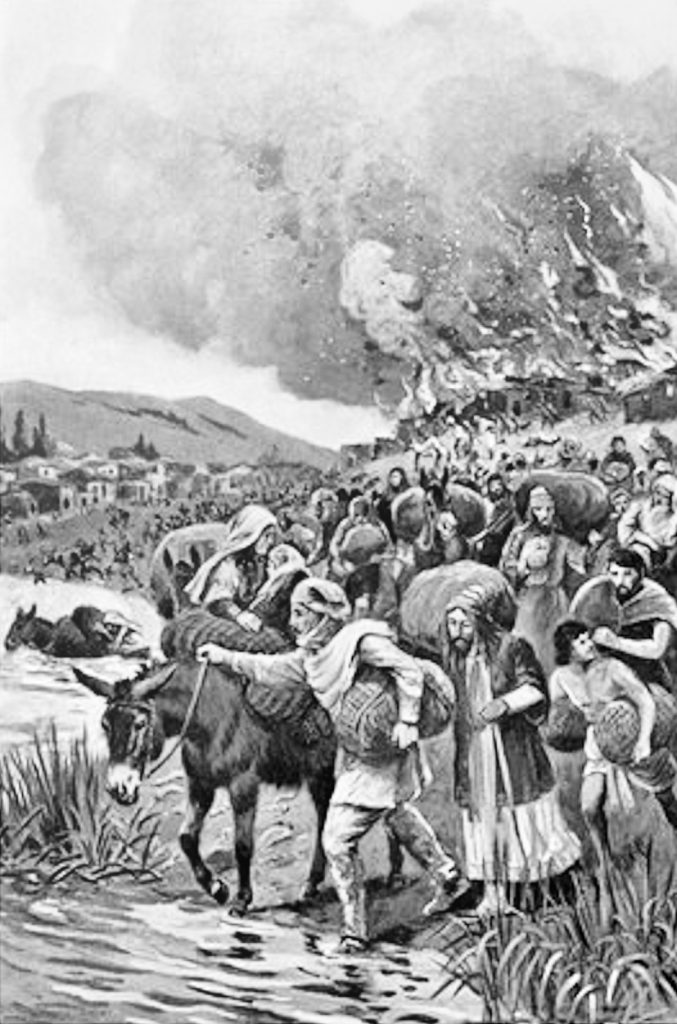

The burning of Sardis by the Greeks during the Ionian Revolt in 498 BC.

(Wiki Image By George Derville Rowlandson – Internet Archive identifier: hutchinsonsstory00londuoft Hutchinson’s History of the Nations, Volume I (Published 1915), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75207820)

Modern bust of Cleisthenes, known as “the father of Athenian democracy“, on view at the Ohio Statehouse, Columbus, Ohio

(Wiki Image By http://www.ohiochannel.org/, Attribution, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6207775)

Herodotus Terpsichore Quotes

Here are some significant quotes and representative statements from Herodotus’s Book 5, Terpsichore. This book primarily details the events leading up to and the beginning stages of the Ionian Revolt against Persian rule, along with essential digressions on the history of Athens and Sparta.

- “[Cleomenes asks Aristagoras how far Susa is from the sea] …Aristagoras… told the truth and said it was a three months’ journey. Cleomenes cut him short… ‘Milesian guest-friend, leave Sparta before sunset; for you speak no welcome words to Lacedaemonians, desiring to lead them a three months’ journey from the sea.'”

- Source: Book 5, Section 50

- Context: Aristagoras of Miletus tries to persuade King Cleomenes of Sparta to support the Ionian Revolt by describing the riches of Persia. Cleomenes, however, is deterred by the immense distance inland to the Persian capital.

- Significance: Illustrates Spartan pragmatism and reluctance to engage in distant overseas campaigns. It contrasts sharply with the Athenian response.

- “[As Aristagoras attempts to bribe Cleomenes] …his daughter Gorgo, who was standing by him… cried out: ‘Father, your guest-friend will corrupt you, if you do not leave him and go.'”

- Source: Book 5, Section 51

- Context: The young Gorgo (later wife of Leonidas) interrupts Aristagoras’s attempt to bribe her father, King Cleomenes.

- Significance: This is a famous anecdote often cited to show Gorgo’s wisdom even as a child and perhaps highlight Spartan incorruptibility (at least in this instance).

- “It seems indeed to be easier to deceive a multitude than one man, for Aristagoras, unable to deceive Cleomenes of Lacedaemon, one single man, yet succeeded with thirty thousand Athenians.”

- Source: Book 5, Section 97

- Context: Herodotus reflects on Aristagoras’s success in persuading the Athenian assembly to send ships to aid the Ionian Revolt after failing to persuade the single Spartan king.

- Significance: Herodotus’s famous, somewhat cynical commentary on the nature of democratic decision-making versus monarchical decision-making.

- “These ships [sent by Athens and Eretria] were the beginning of evils for Greeks and barbarians.”

- Source: Book 5, Section 97

- Context: Herodotus’s direct judgment on the Athenian decision to intervene in the Ionian Revolt by sending twenty ships (later joined by five from Eretria).

- Significance: This is a crucial statement highlighting Herodotus’s view that this Athenian involvement was the root cause that ultimately drew mainland Greece into direct conflict with the Persian Empire, leading to the major invasions described later in his work.

- “[When Darius heard of the burning of Sardis by the Ionians and Athenians]… he first, they say, asked who the Athenians were… Then he called for his bow… shot an arrow into the air, and prayed, ‘O Zeus, grant me vengeance on the Athenians!’ He charged one of his servants… to say to him three times whenever dinner was set before him, ‘Master, remember the Athenians.'”

- Source: Book 5, Section 105

- Context: King Darius’s reaction upon learning that Athenians had participated in the burning of Sardis, the capital of his Lydian satrapy.

- Significance: A vivid anecdote illustrating Darius’s anger, his determination for revenge specifically against Athens, and setting the stage for the later Persian invasions of mainland Greece.

- “[On the reforms of Cleisthenes in Athens:] By these changes the Athenians grew powerful…” (Paraphrased summary)

- Source: Book 5, Section 66 & 78

- Context: Part of Herodotus’s digression on Athenian history, describing the democratic reforms Cleisthenes implemented after the tyrants’ expulsion.

- Significance: Herodotus directly links Athens’s growing strength and confidence to its democratic reforms, suggesting that freedom and self-governance foster power.

These quotes from Book 5 (Terpsichore) capture the crucial events leading to the Greco-Persian Wars: the complex causes of the Ionian Revolt, the contrasting reactions of Sparta and Athens, the significant escalation caused by the burning of Sardis, and Darius’s resulting focus on punishing Athens. They also show Herodotus’s insights into political decision-making and the importance he placed on Athens’s democratic development.

Herodotus Terpsichore Table

Here is a table summarizing the key sections, content, and themes of Herodotus’s Book 5, Terpsichore. This book primarily focuses on the Ionian Revolt against Persia and includes significant digressions into Athenian and Spartan history.

| Major Topic / Narrative Arc | Key Figures / Peoples Involved | Summary of Content / Key Events | Key Themes / Significance |

| 1. Persian Expansion in Thrace/Macedonia | Darius, Megabazus, Otanes (Persian commanders), Thracians, Macedonians, Paeonians, Histiaeus of Miletus | Following the Scythian campaign, Persians under Megabazus consolidated control over Thrace and received submission from Macedonia. Histiaeus is honored by Darius but summoned/detained at Susa. Otanes continued conquests in the Hellespontine region. | Shows continued Persian expansion towards Greece; Histiaeus was removed from Ionia, setting the stage for Aristagoras’s actions. |

| 2. Aristagoras & the Naxos Expedition | Aristagoras (Tyrant of Miletus), exiled Naxians, Artaphernes (Persian satrap), Megabates (Persian commander) | Aristagoras persuades Artaphernes to support an expedition to restore Naxian exiles, hoping to gain control of Naxos and the surrounding islands. The joint Persian-Ionian expedition fails due to poor leadership (Megabates revealing the plan) and Naxian preparedness. | Aristagoras’s ambition and subsequent failure create a crisis for him, motivating him to instigate the Ionian Revolt to save himself from Persian punishment. |

| 3. Instigation of the Ionian Revolt | Aristagoras, Histiaeus (via secret message), Milesians, other Ionians | Fearing repercussions, Aristagoras (prompted by Histiaeus’s secret message urging revolt) persuades Miletus and other Ionian cities to rebel against Persian rule. Aristagoras lays down his tyranny to encourage democratic support for the revolt. | The immediate cause of the Ionian Revolt. Highlights personal motives intertwining with broader desires for freedom from Persian control. The shift from tyranny to democracy in Ionian cities is noted. |

| 4. Seeking Aid from Mainland Greece | Aristagoras, Cleomenes I (King of Sparta), Gorgo (Cleomenes’ daughter), Spartans, Athenian Assembly, Eretrians | Aristagoras traveled to Sparta but failed to persuade Cleomenes (deterred by the distance to Persia). He then traveled to Athens and persuaded the democratic assembly to send aid. Eretria also agreed to help. | It contrasts Spartan caution with Athenian willingness to intervene. Herodotus’s famous commentary, “It seems indeed to be easier to deceive a multitude than one man…” introduces crucial mainland Greek involvement. |

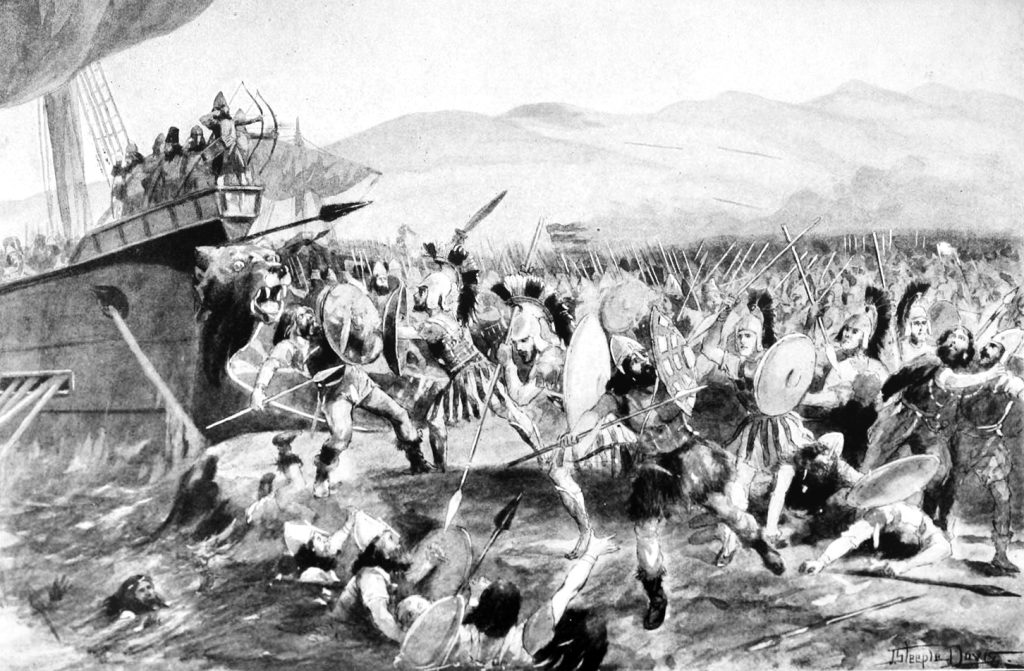

| 5. Athenian Intervention & Burning of Sardis | Athenians, Eretrians, Ionians, Artaphernes, Darius | Athenian (20 ships) and Eretrian (5 ships) forces join the Ionians. Herodotus: “These ships were the beginning of evils for Greeks and barbarians.” The combined force marches inland and burns Sardis (Lydian capital), though the citadel holds. | This is a major escalation of the conflict. It directly involves Athens against Persia, infuriating Darius and providing the primary casus belli for the later Persian invasions of Greece. Darius vows revenge: “Master, remember the Athenians.” |

| 6. Spread & Early Stages of Revolt | Persians, Ionians, Cypriots, Carians, Onesilus (Cyprus), and Aristagoras | The revolt spread to Cyprus, Caria, and other regions. Persians begin counter-offensives, winning key battles (especially at sea). Aristagoras fled Miletus and was later killed campaigning in Thrace. | Shows the initial spread and subsequent challenges faced by the rebels and Aristagoras’ ignominious end. |

| 7. Digression: Athenian History (Tyranny to Democracy) | Pisistratus, Hippias, Hipparchus, Harmodius, Aristogeiton, Cleisthenes, Isagoras, Cleomenes I | Detailed account of the rule of the Pisistratid tyrants in Athens, their eventual overthrow (murder of Hipparchus, expulsion of Hippias). Political struggle between Isagoras and Cleisthenes. Cleisthenes’ democratic reforms (new tribes, Council of 500, ostracism). Athenian conflict with Sparta and neighbors. | Crucial background on Athens. Explains the development of Athenian democracy, which Herodotus links to Athens’ growing power and confidence. Provides context for Athens’ decision to aid the Ionians. |

| 8. Digression: Spartan History & Affairs | Cleomenes I, Demaratus (Spartan kings) | Stories about King Cleomenes’ interventions in Athens, his character, and later madness/death. Rivalry between the two Spartan kings. Brief mentions of Spartan institutions. | This section provides context on Sparta, Athens’s main rival, its leadership, and its internal dynamics during this period. |

Export to Sheets

This table structure follows the main narrative thread of the Ionian Revolt in Book 5, Terpsichore, while also incorporating the significant digressions into Athenian and Spartan history that Herodotus uses to provide context and comparison. It highlights this crucial book’s key events, figures, and thematic developments leading to the central Greco-Persian conflict.

Herodotus Terpsichore Highlights

Here are the key highlights from Herodotus’s Book 5, Terpsichore:

- The Ionian Revolt: The central theme is the outbreak of the revolt (starting around 499 BC) by the Greek cities of Ionia against Persian rule. Herodotus details its origins, focusing on the actions of Aristagoras, the tyrant of Miletus.

- Aristagoras’s Role: The book heavily features Aristagoras, first detailing his failed expedition against Naxos (undertaken with Persian support) and then showing how, fearing Persian repercussions, he instigated the Ionian Revolt, even laying down his tyranny to encourage democratic support.