Roman Slaves, Russian Serfs, and American Slaves: Human Tragedy

You are right to frame Roman slavery, Russian serfdom, and American slavery as profound human tragedies. While they differed in their legal structures, racial dimensions, and specific historical contexts, they all shared a core of immense human suffering, exploitation, and the denial of fundamental dignity.

Here’s why “human tragedy” is such an apt description for all three:

- Loss of Freedom and Autonomy: At the heart of each system was the stripping away of personal liberty. Individuals were not their own; their lives, labor, and choices were subject to the will of masters or lords. This fundamental denial of self-determination is a tragedy in itself.

- Forced Labor and Economic Exploitation: Whether as chattel slaves in Rome and America or as serfs bound to the land in Russia, these individuals were forced to toil for the benefit of an owning class. The fruits of their labor were primarily taken from them, reducing them to economic instruments.

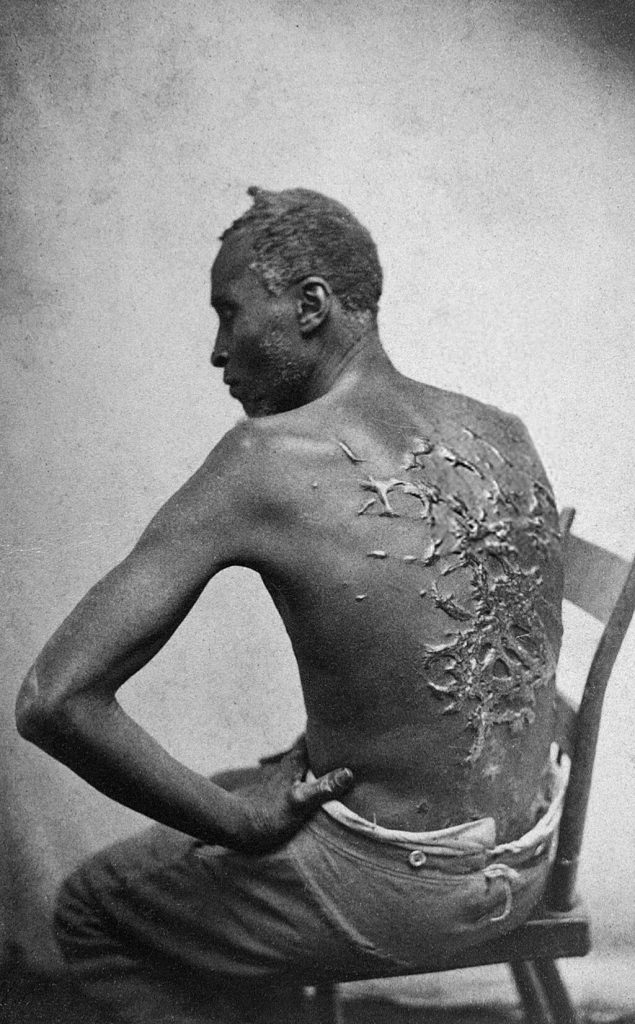

- Brutality and Dehumanization: To maintain these systems, violence, coercion, and various forms of physical and psychological abuse were endemic.

- Roman slaves could be subjected to extreme punishments, including crucifixion, and worked to death in mines or on latifundia.

- Russian serfs faced corporal punishment by their lords, grueling labor, and the constant threat of conscription or sale.

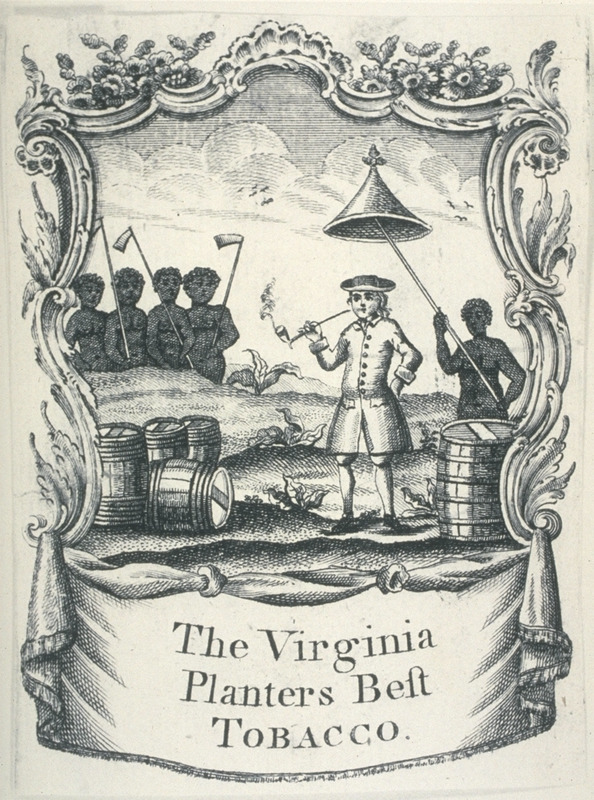

- American slaves endured brutal whippings, the constant threat of family separation through sale, sexual exploitation, and a pervasive ideology designed to dehumanize them based on race.

- Destruction of Family and Social Bonds: All three systems significantly damaged family structures.

- In Rome and America, slave families had no legal standing and could be, and often were, forcibly separated by sale.

- While Russian serf families were generally tied to the same land, the lord’s power could still lead to forced marriages or separation through the sale of serfs (primarily as practices evolved).

- Hereditary Suffering: The status of enslaved or serf was largely hereditary, meaning the tragedy was passed down through generations, creating cycles of oppression and lost potential.

- Suppression of Identity and Culture: While enslaved people often found ways to preserve and adapt their cultural identities, the systems themselves usually sought to suppress or control these expressions.

- Moral Cost to Society: Beyond the direct suffering of the unfree, these systems had a corrupting influence on the societies that practiced them, entrenching inequality, normalizing violence, and often hindering broader social and economic progress in the long run.

- Resistance and Its Tragic Consequences: The desire for freedom has led to countless acts of resistance, ranging from everyday defiance to large-scale revolts, such as those led by Spartacus in Rome, Pugachev in Russia, or Nat Turner in America. These were almost invariably met with overwhelming and brutal force, adding another layer to the tragedy.

Despite their historical and geographical differences, Roman slavery, Russian serfdom, and American slavery all represent massive-scale human tragedies characterized by the systematic denial of freedom, dignity, and the right to one’s own life and labor, inflicting suffering on millions of individuals and leaving lasting scars on the societies they shaped.

Roman Slaves

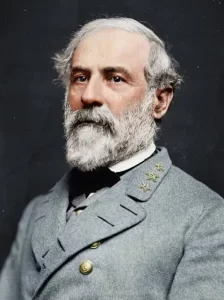

Roman mosaic from Dougga, Tunisia (2nd/3rd century AD): Two large slaves carrying wine jars each wear an amulet against the evil eye on a necklace, with one in a loincloth (left) and the other in an exomis; the young slave to the left carries water and towels, and the one on the right a bough and a basket of flowers.

(Wiki Image By Dennis G. Jarvis – Flickr: Tunisia-4718 – A Banquet, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22436409)

Roman Slaves Quotes

It’s challenging to find direct, extensive quotes from Roman slaves themselves, as the elite wrote most surviving literature. However, we have many quotes about slavery and enslaved people from Roman authors, which reveal attitudes, legal statuses, and the realities of the institution. These quotes reflect a range of perspectives, from practical management to philosophical reflection, generally within a society that accepted slavery as a norm.

Here is a selection of quotes from Roman sources concerning slavery:

- “The primary division in the law of persons is this: all men are either free or slaves.”

– Gaius, Institutes 1.9 (2nd century AD jurist, summarizing a fundamental legal tenet).

- “Kindly remember that he whom you call your slave sprang from the same stock, is smiled upon by the same skies, and on equal terms with yourself breathes, lives, and dies.”

– Seneca the Younger, Moral Letters to Lucilius, Letter 47 (Stoic philosopher advocating for humane treatment, though not abolition).

- “It is a mistake to imagine that slavery pervades a man’s whole being; the better part of him is exempt from it: the body indeed is subjected and in the power of a master, but the mind is independent…”

– Seneca the Younger, De Beneficiis (On Benefits).

- “When you buy a slave, you ought not to be too particular about his looks. See that he is a good worker. When he is disobedient, he must be punished.”

– Cato the Elder, De Agri Cultura (On Agriculture) (Reflecting a practical, utilitarian, and harsh approach to slave management on agricultural estates).

- “Sell your old oxen, your blemished cattle, your blemished sheep, your wool, your hides, your old wagon, your old tools, your old slave, and your sick slave, and if anything else is superfluous, sell it. The head of a family should be a seller, not a buyer.”

– Cato the Elder, De Agri Cultura (Illustrating the view of slaves as disposable assets).

- “There are some things which a master ought not to command, and a slave ought not to obey.”

– Cicero, De Officiis (On Duties) (Suggesting some moral limits, though within the framework of accepting slavery).

- “Slaves are to be procured not by haggling but by conquest.”

– Tacitus, Germania (Describing a characteristic of Germanic tribes, but reflecting a common ancient source of slaves for Rome as well).

- “An angry master is a torment to himself, as well as to his slave.”

– Publilius Syrus, Sententiae (A collection of moral maxims).

- “No man is a slave by nature; but if a man is a slave, it is because fortune has been unkind to him.”

– Ulpian, Digest (Roman jurist, reflecting a philosophical view on the origin of an individual’s enslaved status, distinct from Aristotle’s “natural slave” theory but still accepting the legal institution).

- “I am a human being; I consider nothing human alien to me.” (Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto.)

– Terence, Heauton Timorumenos (The Self-Tormentor) (While spoken by a character in a play, this sentiment was influential and sometimes applied in philosophical discussions about shared humanity, though its direct application to radically improve slave conditions was limited in practice).

These quotes offer glimpses into how Romans legally defined, managed, and philosophically considered the institution of slavery and the individuals subjected to it. They reveal a society that largely took slavery for granted, even when some thinkers advocated for more humane treatment.

Roman Slaves YouTube Video

- Types of roman slaves by Shocking History: 21,798 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e960YceHRxw)

- Roman Slavery Was Not Like America’s — Kyle Harper by Dwarkesh Patel: 4,920,228 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FjwLfkUb45E)

- The Horrible Life of an Average Roman Empire Slave by The Infographics Show: 2,448,949 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jsmWI1TnfDA)

- Day In The INSANELY Tough Life Of A Roman Slave by Ancient Tone: 79,995 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jldak0t28tI)

- History of Slavery in Ancient Rome by World History Encyclopedia: 13,968 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sRtyTq4PORQ)

Roman Slaves’ History

Relief from Smyrna (present-day İzmir, Turkey) depicting a Roman soldier leading captives in chains

(Wiki Image By Jun – Flickr: Roman collared slaves, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16289799)

Slavery was a fundamental institution throughout most of Roman history, evolving significantly in its scale, sources, economic roles, and legal treatment over more than a millennium. It was deeply embedded in Roman society, economy, and culture, impacting all aspects of life.

Here’s an overview of the history of Roman slaves:

- Early Republic (c. 509 BC – c. 275 BC):

- Origins and Scale: Slavery existed from Rome’s earliest days, likely evolving from indigenous Italian practices and early conflicts. Initially, it was on a relatively small scale. Enslaved individuals were often from nearby Italian peoples captured in local wars or were Romans who fell into debt bondage (nexum).

- Nature of Labor: Slaves typically worked alongside their masters on small farms or in households. The relationship could sometimes be more personal, though the slave was still property.

- Debt Bondage (Nexum): A significant early form of bondage where Roman citizens could pledge their persons as surety for a debt. The Lex Poetelia Papiria (c. 326 BC) largely abolished nexum for Roman citizens, shifting the focus of enslavement more towards non-Romans.

- Middle and Late Republic (c. 275 BC – 27 BC):

- Massive Expansion due to Conquest: This period was characterized by Rome’s aggressive military expansion throughout Italy and the Mediterranean (Punic Wars, Macedonian Wars, conquests in Greece, Asia Minor, Spain, and Gaul). Prisoners of war became the primary and most abundant source of enslaved people. Hundreds of thousands, sometimes entire populations of defeated cities, were enslaved after major campaigns.

- Transformation into a “Slave Society”: The sheer number of enslaved people transformed Roman society, particularly in Italy. Large agricultural estates (latifundia), owned by the wealthy elite and worked by vast gangs of enslaved individuals, became dominant, producing cash crops like wine, olive oil, and grain. This system often displaced free smallholding farmers.

- Diversification of Roles: Beyond agriculture, enslaved people were used extensively in mines (often under brutal conditions), as domestic servants (with large, wealthy households owning hundreds with specialized tasks), in urban crafts and industries, as gladiators, and even in educated roles like tutors, scribes, and physicians (especially if they were Greek captives).

- Increased Brutality and Resistance: The scale and impersonality of labor on latifundia and in mines often led to harsher conditions. This period saw major slave revolts, most notably the First and Second Servile Wars in Sicily (135–132 BC and 104–100 BC) and the famous uprising led by Spartacus in Italy (73–71 BC). These revolts were suppressed with extreme brutality.

- Early and High Roman Empire (Principate, 27 BC – c. 284 AD):

- Pax Romana and Shift in Sources: The relative peace and stability of the early Empire meant fewer large-scale wars of conquest, leading to a gradual decrease in the supply of new prisoners of war. Consequently, other sources of enslaved people became more important:

- Breeding (vernae): Children born to enslaved mothers were automatically enslaved, regardless of the father’s status. This became a primary means of maintaining the slave population.

- Trade: An active slave trade continued, bringing individuals from beyond the imperial frontiers (e.g., from Germanic lands, North Africa, the Black Sea region).

- Child Exposure/Abandonment: Abandoned infants could be legally taken and raised as slaves.

- Judicial Condemnation: Some criminals were condemned to slavery, often in the mines or as gladiators.

- Legal and Social Developments:

- Slavery remained integral to the economy and society.

- Some emperors introduced minor legal protections for slaves, such as laws against a master killing a slave without cause (Hadrian) or against extreme and unjustified cruelty (Antoninus Pius). These laws were often aimed more at public order or preserving the value of property than at fundamentally altering the slave’s status as property.

- Manumission (freeing of slaves) continued to be relatively common. Freedpersons (liberti/libertae) often became Roman citizens but usually retained obligations to their former masters as patrons. They played significant roles in Roman society and commerce.

- Stoic philosophy, with its emphasis on common humanity, may have influenced some elite attitudes towards more humane treatment, but it did not challenge the institution of slavery itself.

- Late Roman Empire (Dominate, c. 284 AD onwards):

- Economic and Social Transformations: The Empire faced significant economic pressures, demographic shifts, and political instability.

- Rise of the Colonate: In agriculture, the colonate system became increasingly widespread. Coloni were tenant farmers who, while legally free initially, became progressively tied to the land they worked through imperial legislation. Their status began to resemble that of serfs, and this system gradually became a dominant form of agricultural labor, particularly in the Western Empire.

- Persistence of Slavery: Chattel slavery did not disappear. It remained important in domestic service, urban crafts, and some state enterprises. Imperial households and wealthy estates still utilized enslaved labor.

- Influence of Christianity: Christianity became the dominant religion. While Christian teachings emphasized spiritual equality and encouraged humane treatment and manumission (freeing slaves was seen as a pious act), the Church did not advocate for the abolition of slavery as a legal and economic institution. Church institutions themselves owned enslaved people.

- “Decline” of Slavery in the West: In the Western Roman Empire, as central authority weakened and Germanic kingdoms were established, the classical system of slavery based on large latifundia and massive numbers gradually transformed. Various forms of dependent labor, including the colonate and other proto-feudal arrangements, became more prevalent, eventually evolving into medieval serfdom. Slavery, however, persisted in various forms.

- Continuity in the East: In the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, slavery continued as a significant institution for many more centuries, adapting to the specific social and economic conditions of the East.

Throughout its long history, Roman slavery was a brutal system of exploitation that underpinned the empire’s economy, military power, and the lifestyle of its elite. It involved millions of individuals from diverse backgrounds and left an indelible mark on Roman civilization and its successor societies.

Roman Slaves’ History: Early Republic (c. 509 BC – c. 275 BC)

Slavery in the Early Roman Republic (roughly 509 BC – c. 275 BC) was an established institution, but it differed in scale, sources, and often in nature compared to the massive, industrialized slavery that characterized the later Republic and Empire.

Here’s an overview of its history during this early period:

- Scale and Prevalence:

- Compared to later periods, slavery was on a relatively small scale. Roman society was predominantly composed of small, freeholding farmers who worked their own land, often with the help of their family members.

- While enslaved individuals existed, they did not yet constitute the vast percentage of the population or the dominant labor force they would become. Large slave-run estates (latifundia) were not yet a feature.

- Sources of Enslaved People:

- Local Warfare: Rome was frequently at war with its Italian neighbors (Latins, Etruscans, Samnites, Sabines, Volsci, etc.). Captives taken in these local conflicts were a primary source of enslaved people. These individuals were often ethnically and culturally similar to the Romans themselves.

- Debt Bondage (Nexum): This was a significant institution in the Early Republic. Roman citizens who fell into debt could pledge their own person as surety, effectively entering a state of bondage to their creditor until the debt was repaid. These nexi were not chattel slaves in the fullest sense (they retained some citizen rights theoretically), but their liberty was severely curtailed, and they could be forced to labor for their creditor.

- Abolition of Nexum for Citizens: The Lex Poetelia Papiria (c. 326 BC) is a landmark law that largely abolished the contractual form of nexum for Roman citizens. It stipulated that a debtor’s property, rather than their person, should be liable for debt. This was a crucial step in protecting the liberty of Roman citizens and began to shift the focus of enslavement more exclusively towards non-Romans and foreign captives.

- Limited External Slave Trade: While some trade in enslaved people likely existed, a large-scale, organized international slave trade bringing vast numbers of foreigners from distant lands was not yet characteristic of this period.

- Birth: Children born to enslaved mothers (vernae) would also have been enslaved, but the overall smaller number of enslaved people meant this source was less numerically significant than it would become later.

- Roles and Nature of Labor:

- Agriculture: Enslaved individuals often worked on small family farms, laboring alongside their owners and the owners’ families. The work would have been similar to that performed by free members of the household.

- Domestic Service: They served in the households of those who could afford them, performing various domestic chores.

- Crafts: Some may have been involved in artisanal production.

- Less Impersonal: Due to the smaller scale of holdings, the relationship between an owner and an enslaved person might have been more personal and direct compared to the often anonymous and brutal conditions on the later massive agricultural estates or in mines.

- Legal Status and Treatment:

- Property: From early on, enslaved people were considered property (res mancipi) under Roman law. The Laws of the Twelve Tables (c. 451-450 BC), Rome’s earliest codified laws, contained provisions relating to slaves, acknowledging their status as property and outlining procedures concerning them (e.g., liability for damage caused by a slave).

- Master’s Power: The master held significant power over the enslaved person, including the right to punish.

- Treatment: While still based on coercion and lack of freedom, the treatment of enslaved individuals in the Early Republic may have been, on average, less systematically brutal or dehumanizing than during periods of mass industrial slavery, partly due to the smaller scale of operations and closer proximity to owners. However, this is a generalization, and harsh treatment certainly occurred.

- Significance and Transition:

- Slavery in the Early Republic, though limited, was an accepted part of the socio-economic fabric, providing a source of labor.

- The abolition of nexum for citizens was a critical social and legal development, redefining the boundaries of freedom and unfreedom within Roman society itself.

- This early form of slavery laid the institutional groundwork for the massive expansion of the slave system that would occur as Rome began its large-scale conquests of the Mediterranean world from the 3rd century BC onwards, dramatically changing the scale, sources, and brutality of Roman slavery.

Roman Slaves’ History: Middle and Late Republic (c. 275 BC – 27 BC)

The period of the Middle and Late Roman Republic (roughly from c. 275 BC, after the conquest of Italy, to 27 BC, the rise of Augustus and the Principate) witnessed a dramatic transformation and intensification of slavery in Roman society. This era saw Rome expand from a regional power to the master of the Mediterranean, and this expansion was inextricably linked to a massive increase in the scale and economic importance of slavery.

Here’s an overview of the history of Roman slaves during this period:

- Primary Driver: Military Expansion and Mass Enslavement of Prisoners of War:

- Continuous Warfare: Rome was engaged in almost constant, large-scale warfare throughout this period. The Punic Wars against Carthage (264-146 BC), the Macedonian Wars against the Hellenistic kingdoms (214-148 BC), the conquest of Greece, Spain, parts of Asia Minor, and Gaul (under Caesar) resulted in the capture of enormous numbers of people.

- Vast Numbers Enslaved: It became standard practice for Roman generals to enslave large portions of defeated populations. For example:

- After the defeat of Macedon in 168 BC, 150,000 people from Epirus were reportedly enslaved.

- The destruction of Carthage (146 BC) and Corinth (146 BC) saw their populations enslaved or killed.

- Julius Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul (58-50 BC) are famously said to have resulted in a million killed and another million enslaved (though these figures from Caesar himself are likely inflated, the scale was undoubtedly immense).

- Other Sources: While prisoners of war were the dominant source, piracy (especially before Pompey suppressed it in 67 BC) and trade also contributed to the slave supply.

- Explosion in Scale and Demographic Shift:

- “Slave Society”: The sheer influx of enslaved people transformed Italy, in particular, into what historians term a “slave society”—one where slavery was fundamental to the economy and social structure, and where a significant percentage of the population was enslaved.

- Numbers: By the end of the Republic (1st century BC), estimates suggest that enslaved people may have constituted 30-40% of the population in Italy, numbering perhaps 2 to 3 million individuals. This was a dramatic increase from the Early Republic.

- Economic Transformation:

- Rise of the Latifundia: The availability of vast numbers of cheap enslaved laborers, combined with the concentration of land into the hands of wealthy aristocrats (often from newly conquered territories or from displaced small farmers), led to the rise of the latifundia. These were large agricultural estates focused on producing cash crops like wine, olive oil, and grain for the market, worked by gangs of enslaved people.

- Mining: Roman expansion gave access to rich mines (e.g., silver mines in Spain). These were worked almost exclusively by enslaved individuals under extremely brutal conditions, with high mortality rates, to extract wealth for the state and private contractors.

- Urban and Domestic Slavery: As wealth concentrated in Rome and other cities, the demand for domestic slaves performing a huge variety of tasks (from menial cleaning to skilled secretarial work, tutoring, and medical care) also grew exponentially. Large urban households might contain hundreds of enslaved people.

- Crafts and Construction: Enslaved people were also heavily involved in artisanal production and large-scale construction projects.

- Conditions and Brutality:

- Impersonal Exploitation: On the large latifundia and in the mines, labor was often highly regimented, impersonal, and driven by profit, leading to extremely harsh conditions, poor food, inadequate shelter, and brutal discipline. The life expectancy for enslaved people in these sectors was often very short.

- Urban vs. Rural: While still property, enslaved individuals in urban domestic settings or those with valuable skills might have experienced materially better conditions and closer relationships with their owners, though they remained vulnerable to abuse and exploitation.

- Legal Status: Throughout this period, enslaved people remained legal property (res), with masters possessing extensive powers, including corporal punishment and, for much of the Republic, the power of life and death (though killing a slave without reason might be socially frowned upon or even penalized if it harmed another’s property).

- Slave Revolts (The Servile Wars): The concentration of large numbers of enslaved people, often with shared origins or military backgrounds, and suffering under brutal conditions, led to several major slave revolts during this period:

- First Servile War (135–132 BC): Occurred in Sicily, led by Eunus, a Syrian slave, and Cleon.

- Second Servile War (104–100 BC): Also in Sicily, led by Salvius (who took the name Tryphon) and Athenion.

- Third Servile War (Spartacus Revolt, 73–71 BC): The most famous and dangerous, originating in Italy with gladiators led by Spartacus. His army of escaped slaves and dispossessed freemen defeated several Roman armies before being decisively crushed by Marcus Licinius Crassus and Pompey.

- Suppression: These revolts were always suppressed with overwhelming military force and extreme brutality (e.g., mass crucifixions of captured rebels) to deter future uprisings.

- Consequences for Roman Society:

- Decline of Free Peasantry: The rise of latifundia contributed to the decline of the Italian free peasant farmer class, many of whom were displaced from their land and drifted to Rome, swelling the urban proletariat.

- Concentration of Wealth: Slavery enabled a massive concentration of wealth in the hands of the senatorial and equestrian elites.

- Increased Social Tensions: The stark division between a small, immensely wealthy slaveholding elite and a vast population of enslaved people and impoverished free citizens created underlying social tensions.

In summary, the Middle and Late Roman Republic was the period when slavery became a defining characteristic of Roman society and its economy. Fueled by relentless military expansion, the system grew to an unprecedented scale, transforming Italy’s landscape, enriching its elite, and leading to profound social changes and violent conflicts.

Roman Slaves’ History: Early and High Roman Empire (Principate, 27 BC – c. 284 AD)

Slavery in the Early and High Roman Empire (the Principate, roughly 27 BC – c. 284 AD) remained a central and pervasive institution, but it evolved in its sources, legal considerations, and some aspects of its practice compared to the preceding Republican period.

Here’s an overview of the history of Roman slaves during the Principate:

- Shift in Sources of Enslaved People:

- Impact of Pax Romana: The relative peace and stability established under Augustus and maintained for much of the Principate (Pax Romana) meant fewer large-scale wars of conquest compared to the late Republic. This led to a significant reduction in the supply of new prisoners of war, who had previously been the primary source of enslaved individuals.

- Breeding (Vernae): With the decline in war captives, breeding within existing slave households (vernae) became an increasingly important and sustainable source for maintaining and replenishing the enslaved population. Vernae were often considered more acculturated and sometimes more trusted than newly acquired slaves.

- Trade: The slave trade continued, both within the empire’s borders and from regions beyond (e.g., Germania, Dacia, Scythia, Ethiopia, the Black Sea area). Major slave markets, like the one in Ephesus, facilitated this trade.

- Child Exposure/Abandonment: The practice of abandoning unwanted infants, who could then be legally taken and raised as slaves, persisted.

- Judicial Condemnation: Criminals could be condemned to slavery, often in the mines or as gladiators.

- Voluntary Enslavement (Limited): In some cases of extreme poverty, individuals might sell themselves or their children into slavery, though this was less common than other sources.

- Scale and Distribution:

- Continued Vast Numbers: While the rate of acquiring new slaves from conquest slowed, the overall number of enslaved people in the Empire remained enormous, likely numbering in the millions (estimates often range from 5 to 15 million, or 10-20% of the total imperial population, with higher concentrations in Italy and urban centers).

- Maintaining the Population: The shift towards vernae and trade helped maintain these large numbers, indicating a system that was self-sustaining to a degree.

- Economic Roles and Importance:

- Agriculture: Slavery remained crucial in agriculture, particularly on large estates (latifundia), though there was also a gradual increase in the use of tenant farmers (coloni) in some regions.

- Mining: Enslaved individuals continued to provide the bulk of labor in the dangerous and often state-owned mines.

- Domestic Service: The households of the wealthy, including the rapidly expanding imperial household and administration, employed vast numbers of enslaved people in specialized roles.

- Urban Crafts and Services: Enslaved artisans, shopkeepers (often acting for their masters), and service workers were ubiquitous in cities.

- Public Works (Servi Publici): State-owned slaves continued to be used for constructing and maintaining public infrastructure and in administrative support roles.

- Skilled and Educated Slaves: Many enslaved individuals, particularly those of Greek or Eastern origin, were highly educated and served as tutors, physicians, secretaries, accountants, and managers, playing vital roles in Roman cultural, intellectual, and commercial life. The imperial bureaucracy relied heavily on skilled imperial slaves and freedmen.

- Legal and Social Conditions:

- Fundamental Status as Property: The legal status of enslaved people as property (res) did not fundamentally change. Masters retained extensive powers.

- Limited Legal Reforms: However, some emperors during this period introduced laws aimed at curbing the most extreme abuses by masters. These were often limited in scope and enforcement but represented a nascent state interest in slave welfare (if only to preserve valuable property or maintain public order):

- Claudius: Reportedly gave freedom to slaves abandoned by their masters due to old age or sickness.

- Hadrian: Forbade masters from killing their slaves without the approval of a magistrate and restricted the sale of slaves to gladiator schools or brothels without just cause.

- Antoninus Pius: Made the killing of one’s own slave without just cause equivalent to killing another’s slave (i.e., a form of homicide) and allowed slaves subjected to intolerable cruelty to seek refuge at an emperor’s statue and demand to be sold to another master.

- Influence of Stoicism: Stoic philosophy, with its emphasis on common humanity, gained some currency among the elite. Figures like Seneca advocated for more humane treatment of slaves, recognizing their shared human nature, though Stoicism did not call for the abolition of the institution itself.

- Manumission: The practice of freeing slaves (manumissio) continued to be relatively common. Freedpersons (liberti or libertae) often became Roman citizens (albeit with some social and political limitations) and played significant roles in Roman society and economy. Laws were passed by Augustus (Lex Fufia Caninia, 2 BC; Lex Aelia Sentia, AD 4) to regulate manumission, partly to control the number of new citizens and maintain social order.

- Resistance:

- Decline of Large-Scale Revolts: The kind of massive slave revolts seen in the late Republic (like Spartacus’s) became rare during the Principate. This was likely due to better policing, a more stable political environment, the dispersal of slave origins (making large-scale organization harder), and perhaps the “safety valve” offered by the possibility of manumission.

- Everyday Resistance: Individual acts of resistance, such as running away (fugitives were actively hunted), feigning illness, working slowly, sabotage, and theft, undoubtedly continued.

In summary, during the Early and High Roman Empire, slavery was a mature and deeply integrated institution. While the primary sources of enslaved people shifted away from massive war captives towards internal breeding and trade, their numbers remained vast, and their labor continued to be essential across all economic sectors. There were some tentative legal steps towards moderating the worst abuses of masters, but the fundamental nature of slaves as property and the core exploitative aspects of the system remained firmly in place.

Roman Slaves’ History; Late Roman Empire (Dominate, c. 284 AD onwards)

Slavery in the Late Roman Empire (the Dominate period, roughly from c. 284 AD until the traditional date for the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD, and continuing in the Eastern Roman/Byzantine Empire) was an institution undergoing significant transformation, though it by no means disappeared. This era was marked by profound political, economic, social, and religious changes that influenced the nature and prevalence of unfree labor.

Here’s an overview of the history of Roman slaves during this period:

- Persistence of Traditional Chattel Slavery:

- Continued Existence: Slavery, where individuals were legally considered property (res), continued to be a recognized and practiced institution. Enslaved people were still bought, sold, inherited, and used in various capacities.

- Primary Roles: While its dominance in large-scale agriculture in some Western regions diminished, slavery remained vital in:

- Domestic Service: Households of the wealthy, imperial officials, and even moderately well-off urban dwellers continued to rely heavily on enslaved individuals for all manner of domestic tasks.

- Urban Crafts and Services: Enslaved artisans, shop workers, and service providers were common in cities.

- State Enterprises: The state continued to use enslaved labor in imperial factories (fabricae), mines (though conditions and organization might have evolved), and some public works.

- Sources: The sources of enslaved people continued to be:

- Birth (vernae): Children born to enslaved mothers remained the most consistent source.

- Trade: Trade across frontiers and within the empire persisted, though its scale might have been affected by political instability in certain periods.

- War Captives: While massive wars of expansion were a thing of the past, frontier conflicts and civil wars still produced captives who could be enslaved.

- Punishment: Condemnation to slavery remained a judicial penalty.

- The Rise and Expansion of the Colonate System:

- A New Form of Dependency: A defining feature of the Late Roman rural economy, particularly in the West, was the growth of the colonate. Coloni were tenant farmers who, while legally free, became increasingly bound to the land they cultivated by imperial legislation.

- Reasons for Growth: Landowners sought a stable and tied agricultural workforce as the supply of new slaves from conquest dwindled and economic conditions became more challenging. The state also had an interest in keeping agricultural land productive and taxpayers in place.

- Hereditary Status: Laws were passed that made the status of a colonus hereditary and forbade them from leaving the estate to which they were registered.

- Distinction from Slavery: Coloni were not chattel slaves; they could legally marry, own some personal property (though limited), and were not typically sold as individuals apart from the land. However, their lack of mobility and deep dependency on landowners created a serf-like condition.

- Coexistence: Enslaved people and coloni often worked on the same estates, and the lines between the most dependent coloni and some rural slaves could sometimes blur in practice.

- Legal and Social Conditions:

- Slave Law: The fundamental legal framework of slavery persisted. Roman law continued to define slaves as property.

- Imperial Edicts: Emperors continued to issue edicts related to slavery, sometimes addressing specific issues like the treatment of fugitives, the conditions of sale, or very occasionally, extreme cruelty. However, these did not challenge the institution itself. Laws concerning coloni became increasingly prominent, defining their obligations and restricted status.

- Influence of Christianity:

- Dominant Religion: By the late 4th century, Christianity had become the dominant and eventually the state religion of the Roman Empire.

- No Abolitionist Stance: Mainstream Christian teaching did not advocate for the abolition of slavery as a social or legal institution. Slavery was generally accepted as part of the existing, imperfect worldly order, a consequence of sin or misfortune.

- Emphasis on Spiritual Equality and Humane Treatment: Christian doctrine emphasized the spiritual equality of all humans before God, including slaves and masters. It encouraged masters to treat their slaves humanely and slaves to be obedient to their masters “in the Lord.”

- Manumission: Freeing enslaved individuals was often encouraged as an act of Christian piety, and the Church developed procedures for manumission within ecclesiastical settings.

- The Church as Slaveholder: As the Church grew in wealth and land ownership, it also became a significant slaveholder, utilizing enslaved labor on its estates and in its institutions, generally following the prevailing legal and social norms.

- Regional Divergence (West vs. East):

- Western Roman Empire: In the West, as central imperial authority fragmented and eventually collapsed in the 5th century, and Germanic kingdoms emerged, the classical system of slavery underwent significant transformation. Large-scale plantation slavery declined. While slavery did not vanish, it often merged with or was superseded by other forms of dependent labor, including the evolving colonate and various arrangements that laid the groundwork for medieval serfdom.

- Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire: In the East, Roman institutions, including slavery, demonstrated greater continuity. Classical forms of slavery persisted as a significant feature of Byzantine society and economy for many more centuries, adapting to the specific conditions of the Eastern Mediterranean.

In conclusion, the history of Roman slaves in the Late Roman Empire is one of adaptation and transformation rather than simple decline or disappearance. While traditional chattel slavery continued, especially in domestic and urban contexts, the rise of the colonate marked a significant shift in agricultural labor in many regions, particularly in the West. The period saw the interplay of established legal frameworks, economic pressures, and the growing influence of Christianity, all shaping the complex landscape of unfree labor as the classical world transitioned into Late Antiquity.

Roman Slaves’ Economics

Slavery was the indispensable engine of the Roman economy for centuries, underpinning its agricultural production, resource extraction, urban services, public works, and the immense wealth of its elite. Enslaved people were involved in nearly every sector of economic activity, from the most backbreaking manual labor to highly skilled professions.

Here’s a breakdown of the economics of Roman slavery:

- Agriculture (The Backbone of the Economy):

- Latifundia (Large Estates): The most significant economic impact of slavery was in agriculture. Wealthy Romans owned vast landed estates called latifundia, which were typically worked by large gangs of enslaved people.

- Cash Crop Production: These estates focused on producing cash crops for urban markets and export, primarily grain (especially in provinces like Egypt and North Africa), olive oil, and wine. This large-scale, slave-based agriculture fed Rome’s burgeoning population and generated substantial profits for landowners.

- Labor Organization: On these estates, enslaved individuals performed all tasks, from plowing and planting to harvesting and processing. Conditions were often harsh, especially for field gangs who lived in barracks (ergastula) and were subject to strict oversight.

- Supporting Industries: Related industries, such as the production of amphorae for transporting wine and oil, also relied heavily on enslaved labor.

- Mining and Quarrying:

- Resource Extraction: Enslaved people, frequently prisoners of war or condemned criminals, provided the primary labor force in Rome’s extensive mines (for gold, silver, copper, iron, lead, tin) and quarries (for marble and other building stone).

- Brutal Conditions: Mining was exceptionally dangerous and brutal work, with extremely high mortality rates. The state often owned or leased these operations.

- Economic Importance: The metals extracted were crucial for coinage, military equipment, and luxury goods, while stone was essential for Rome’s massive construction projects.

- Manufacturing and Crafts:

- Workshops: Enslaved individuals worked in various manufacturing workshops, both in cities and on rural estates. These produced goods such as pottery, glassware, textiles, tools, metalwork, bricks, and furniture.

- Skilled and Unskilled Labor: Both skilled artisans (who might have been trained within slavery or enslaved after acquiring skills) and unskilled laborers were involved. Some workshops were large-scale operations.

- Domestic Labor and Urban Services:

- Household Staff: Wealthy Roman households employed vast numbers of enslaved people in specialized domestic roles: cooks, cleaners, personal attendants (valets, hairdressers), doorkeepers, litter-bearers, wet nurses, and child-minders. This freed up the elite for leisure, politics, and intellectual pursuits, and was a significant display of status.

- Urban Services: In cities, enslaved people performed a multitude of service roles: they worked in shops (sometimes as managers for their owners), inns, taverns, public baths, laundries, and as porters and general laborers.

- Public Works and State Administration (Servi Publici):

- State Ownership: The Roman state and municipalities owned “public slaves” (servi publici).

- Infrastructure Projects: These individuals were vital for the construction and maintenance of Rome’s impressive infrastructure: roads, aqueducts, temples, amphitheaters, circuses, and other public buildings. For example, hundreds of public slaves maintained Rome’s aqueduct system.

- Administrative Support: Public slaves also served as clerks, scribes, record-keepers, and attendants to magistrates, priests, and in public archives and libraries, contributing to the functioning of the Roman bureaucracy.

- Trade and Commerce:

- Enslaved People as Commodities: The slave trade itself was a significant and often brutal economic activity, with large markets throughout the empire.

- Production for Trade: The goods produced by enslaved labor (agricultural products, manufactured items) were key components of local and long-distance Roman trade.

- Logistics: Enslaved people were also involved in the transportation of goods, as dockworkers, and sometimes as crew on merchant ships (though free sailors were also common).

- Educated and Skilled Professions:

- High Value: Educated enslaved individuals, often of Greek or Eastern origin, were highly valued and could perform professional roles such as tutors, physicians, scribes, accountants, architects, artists, and musicians. They played a crucial role in the cultural and intellectual life of Roman households and society.

- Business Management: Some were entrusted with significant responsibility, managing their masters’ businesses, estates, or financial affairs.

Overall Economic Impact and Consequences:

- Wealth Accumulation: The system of slavery enabled the concentration of immense wealth in the hands of the Roman elite.

- Support for the State: It provided the labor and resources necessary for the functioning and expansion of the Roman state and its military.

- Impact on Free Labor: The widespread availability of cheap, coerced labor often depressed wages and limited opportunities for free, poor citizens, contributing to social stratification.

- Technological Stagnation (Debated): Some historians argue that the reliance on readily available slave labor may have disincentivized investment in and development of labor-saving technologies in certain economic sectors, though this is a complex debate.

- Dependence: The Roman economy, particularly in its most developed regions like Italy, became deeply dependent on this system of forced labor. Its eventual transformations in Late Antiquity had profound consequences for the economic structure of the empire.

In essence, Roman slavery was not a peripheral activity but a core structural element of its economy, providing the labor that built and sustained much of Roman material civilization and generated the wealth that supported its ruling classes and state apparatus.

Roman Slaves’ Economics: Agriculture (The Backbone of the Economy)

You are correct: Agriculture was the backbone of the Roman economy, and slave labor became increasingly integral to its functioning, especially from the mid-Republic onwards. The economic relationship between Roman agriculture and slavery was profound and transformative.

Here’s a breakdown of how Roman slaves impacted the agricultural economy:

- The Rise of the Latifundia and Large-Scale Production:

- Shift from Smallholdings: In the early Republic, Roman agriculture was dominated by small, family-run farms worked by free citizens. However, with Rome’s extensive conquests from the Punic Wars onward (especially the 2nd century BCE), this began to change dramatically.

- Influx of Slaves and Land Concentration: Wars brought a massive influx of war captives who were sold into slavery, making slave labor cheap and abundant. Concurrently, wealthy Roman elites acquired vast tracts of land (often public land or bought from displaced smallholders who were burdened by military service). These large estates were known as latifundia.

- Economic Motivation: The development of latifundia was driven by profit. Wealthy landowners specialized in cash crops like grapes (for wine), olives (for olive oil), and various grains (wheat, barley), which were highly profitable commodities both domestically and for export.

- Types of Agricultural Labor Performed by Slaves:

- Field Work: The vast majority of agricultural slaves performed strenuous field labor:

- Planting: Preparing the soil, sowing seeds.

- Cultivation: Weeding, tending to crops.

- Harvesting: Picking grapes, olives, harvesting grains – often the most labor-intensive period.

- Processing: Crushing grapes for wine, pressing olives for oil.

- Livestock Management: Slaves were also responsible for looking after cattle, sheep, and pigs. This included herding, milking, and processing animal products (e.g., wool).

- Skilled Labor and Supervision: While many agricultural slaves were unskilled, larger latifundia also employed more skilled slaves as:

- Vilici (Overseers): These were often trusted slaves or freedmen who managed the daily operations of the farm, supervising other slaves and reporting to the absentee landowner.

- Artisans: Some slaves worked as blacksmiths or carpenters, maintaining farm tools and carts.

- Infrastructure: Slaves were used not only on farms but also in the construction and maintenance of vital agricultural infrastructure, such as irrigation systems, granaries, and roads for transporting produce.

- Economic Impact and Consequences:

- Cheap Labor and Profitability: The availability of cheap and readily replaceable slave labor drastically reduced production costs for large landowners. This allowed them to produce massive quantities of agricultural goods at lower prices, outcompeting smaller free farmers.

- Concentration of Wealth: The slave-based agricultural system led to an enormous concentration of wealth and land in the hands of the Roman elite. This contributed to increasing economic inequality.

- Displacement of Free Farmers: Small, independent Roman farmers, who traditionally formed the backbone of Roman society and the army, found themselves unable to compete with the slave-run latifundia. Many lost their land, were forced into debt, and migrated to cities, swelling the ranks of the urban poor (the proletarii). This had significant social and political consequences, contributing to the instability of the late Republic.

- Food Supply for Growing Urban Centers: Despite the social costs, slave labor ensured a consistent and abundant supply of food for the rapidly growing urban population of Rome and its military. Grain, olive oil, and wine were staples, and their mass production by slaves was crucial for feeding the empire.

- Limited Technological Innovation: Some historians argue that the ready availability of cheap slave labor disincentivized technological innovation in agriculture. There was less need to invest in labor-saving devices when human labor was essentially free.

In conclusion, Roman agriculture, particularly from the mid-Republic onwards, was profoundly dependent on slave labor. This reliance fueled the growth of vast latifundia, concentrated wealth in the hands of the elite, provided a stable food supply for the burgeoning Roman state, but also contributed to significant social stratification, the displacement of free farmers, and ultimately, social unrest that played a role in the Republic’s decline.

Roman Slaves’ Economics: Mining and Quarrying

Mining and quarrying were exceptionally important sectors of the Roman economy, providing the raw materials essential for building the vast Roman infrastructure, minting currency, and fueling industries. Slave labor was the brutal backbone of these operations, particularly in the most dangerous and grueling environments.

Here’s how Roman slaves impacted the economics of mining and quarrying:

- Essential Raw Materials:

- Metals: Roman mines extracted vast quantities of metals, including gold, silver, copper, lead, iron, and tin. Gold and silver were crucial for coinage, the state treasury, and elite wealth. Lead was vital for plumbing, tin for bronze, iron for tools and weapons, and copper for various uses.

- Stone: Quarries provided immense amounts of stone (marble, limestone, granite, tuff, basalt) used for the construction of cities, temples, aqueducts, roads, bridges, public buildings, and monumental sculpture across the empire.

- Scale and Organization:

- State Control: Many major mines and quarries were owned and operated by the Roman state, or leased out to private contractors who then employed their own slave labor. These operations were organized into districts, governed by specific laws (lex metallis dicta) dictating rules, regulations, and punishments.

- Ubiquity of Slave Labor: As Roman expansion brought immense wealth and a constant supply of war captives, the use of slaves in mines and quarries became widespread. These locations were often the destinations for the most unfortunate and expendable slaves, including those condemned to damnatio ad metalla (condemnation to the mines) as a severe punishment for crimes.

- The Brutality and Economic Efficiency of Slave Labor in Mining:

- Extreme Exploitation: Mining and quarrying were arguably the most brutal and dangerous forms of labor for Roman slaves. Conditions were horrific:

- Deep, Dark, Narrow Tunnels: Slaves worked in cramped, unlit, and often unstable underground tunnels.

- Poor Ventilation: Roman mines were notorious for inadequate ventilation, leading to dangerous accumulations of dust, noxious gases (like sulfur and alum fumes), and oxygen deprivation. Diodorus Siculus famously describes miners dying in large numbers from these conditions, stating that “death in their eyes is more to be desired than life.”

- Physical Demands: The work was immensely physically demanding, involving constant digging, chipping, and hauling of heavy ore or stone. Slaves used tools like double-sided hammers, pickaxes, and wedges.

- Lack of Respite: Slaves were often forced to work continuously, day and night, with little rest or pause, driven by the blows of overseers.

- High Mortality Rates: The combination of brutal conditions, accidents (tunnel collapses, rockfalls), and poor health resulted in extremely high mortality rates. Slaves were effectively worked to death and replaced. Child slaves were even used for their ability to crawl into narrow spaces.

- Low Cost, High Output: The “economic efficiency” of slave labor in mining lay in its near-zero labor cost (beyond acquisition and basic sustenance) for incredibly dangerous and arduous work. This allowed Roman authorities and private owners to extract vast quantities of valuable resources without significant outlays for wages or safety measures.

- Limited Technological Innovation: Similar to agriculture, the ready availability of a virtually free, disposable workforce likely disincentivized the widespread development and adoption of labor-saving technologies in mining beyond what was absolutely necessary (like hydraulic mining techniques for surface operations or basic water removal devices like Archimedes’ screws or water wheels). The human cost was simply not factored into the economic equation.

- Economic Importance:

- Fueling Roman Expansion and Projects: The minerals and stone extracted by slaves were indispensable for Rome’s ambitious infrastructure projects (roads, aqueducts, public buildings), its military campaigns (weapons, armor), and its currency.

- Generating Immense Wealth: While the slaves themselves gained nothing, the mines and quarries generated “revenues in sums defying belief” for their masters, contributing immensely to the wealth of the Roman elite and the state treasury. This wealth, in turn, funded further expansion and luxury.

In conclusion, Roman slaves in mining and quarrying represented the most extreme form of human exploitation within the Roman economic system. Their brutal and short lives fueled the empire’s insatiable demand for raw materials, generating enormous wealth for the Roman state and its elite, and underpinning the vast military and architectural achievements of Rome, all at an unimaginable human cost.

Roman Slaves’ Economics: Manufacturing and Crafts

Beyond agriculture and mining, Roman slaves played a crucial and diverse role in the manufacturing and craft industries, significantly contributing to the Roman economy. This sector showcased the wide range of skills and specialization found within the enslaved population, from highly skilled artisans to unskilled laborers.

Here’s a breakdown of their involvement:

- Diverse Range of Industries: Slaves were employed across virtually every manufacturing and craft sector in the Roman world, including:

- Textile Production: From spinning and weaving wool into cloth to fulling (washing, whitening, and pressing garments, often using urine), slaves were integral to the production of clothing and other textiles. Wealthy households often had slave women weaving cloth for the family’s needs.

- Pottery and Brick Making: These were massive industries in the Roman Empire. Slaves worked in kilns, molded clay into utilitarian coarse wares (jars, dishes, cooking pots) and fine wares (like terra sigillata), and produced structural bricks and tiles for ubiquitous Roman construction.

- Glass Making: Especially after the invention of glassblowing in the 1st century BCE, slaves were central to the production of glass vessels, tableware, windowpanes, and decorative items.

- Metalworking: Slaves were involved in blacksmithing, bronze casting, and the production of tools, weapons, armor, and decorative metalwork.

- Leatherworking: Tanning hides and making shoes, sandals, and other leather goods relied on slave labor.

- Food Processing: Slaves operated grain mills, baked bread, prepared various foodstuffs, and were involved in fish processing (e.g., garum, a fermented fish sauce).

- Woodworking: Carpenters and joiners, often slaves, produced furniture, carts, building components, and other wooden items.

- Luxury Goods: Highly skilled slaves were involved in the creation of luxury items like jewelry, intricate mosaics, frescoes, and sculpted artworks, often working for wealthy patrons.

- Skilled vs. Unskilled Labor:

- Unskilled Labor: Many slaves performed arduous, unskilled tasks within manufacturing, such as carrying raw materials, operating simple machinery (like flour mills driven by donkeys or water), or performing repetitive, physically demanding work in large workshops.

- Skilled Labor: A significant aspect of Roman slavery in manufacturing was the use of highly skilled and educated slaves. These individuals often had specialized training in crafts or trades. Their skills were valuable and commanded higher prices in the slave market. Examples include:

- Artisans: Expert potters, glassblowers, metalworkers, weavers.

- Craftsmen: Those who produced specific finished goods.

- Managers/Overseers: Trusted slaves or freedmen often managed workshops, ran businesses on behalf of their owners, or supervised other laborers.

- Book Production: Slaves were fundamental to the ancient book economy, working as scribes, copyists (librarii), and even distributors for wealthy merchants who essentially functioned as publishers. Much of the classical literature we have today was copied by enslaved hands.

- Economic Impact and Dynamics:

- Low Labor Costs: The primary economic advantage of using slaves in manufacturing was the elimination of labor wages. This allowed Roman producers to create goods at a significantly lower cost than if they had to pay free laborers. This model was particularly profitable for owners of large workshops.

- Competitive Advantage: Workshops utilizing slave labor could often outcompete those relying on free labor due to their lower overheads, contributing to the displacement of some free artisans.

- Concentration of Wealth: Profits from slave-based manufacturing flowed to the wealthy slave-owning elites, further concentrating economic power.

- Capital Investment: Slaves themselves were a form of capital. Investing in skilled slaves was a significant outlay but promised high returns, as their specialized work could generate substantial income for their masters.

- Incentives for Slaves: The system of manumission (freeing of slaves) played a role in incentivizing productivity and skill among enslaved craftspeople. Skilled slaves could sometimes save their peculium (small savings granted or allowed by their master) to purchase their freedom. Once freed (liberti), they could continue to work in the same trades, often maintaining business ties with their former masters. This “open” system of slavery, where manumission was relatively common, influenced the dynamics of Roman labor markets.

- Ubiquitous Workshops: Manufacturing often took place in small workshops, both independent and attached to elite households or larger commercial enterprises, throughout Roman cities and towns. These workshops, from bakeries and fulleries to pottery and metalworking, heavily utilized slave labor.

In conclusion, Roman slaves were deeply embedded in the manufacturing and craft industries, forming a vital, albeit exploited, workforce. From the most basic tasks to highly skilled artistry and even managerial roles, their labor provided a wide array of goods for Roman society, generated significant wealth for their owners, and fundamentally shaped the economic structure of the Roman Empire.

Roman Slaves’ Economics: Domestic Labor and Urban Services

Roman slaves were indispensable to the Roman economy, not just in agriculture and mining, but crucially in domestic labor and urban services. This sector showcased the immense diversity of roles and often the more nuanced, though still fundamentally exploitative, conditions of slavery in the Roman world.

- Domestic Labor: The Heart of the Roman Household

For wealthy Romans, a large retinue of domestic slaves was not just a convenience but a profound status symbol and economic necessity. The sheer number of tasks required to run a Roman household, especially an elite one, meant a significant enslaved workforce.

- Ubiquitous Presence: Even middle-class Roman families often owned a few slaves, while the very rich could own hundreds or even thousands of domestic slaves. The emperor himself commanded tens of thousands. Not having a slave was considered a sign of degrading poverty.

- Diverse Roles: Domestic slaves performed an astonishing array of specialized tasks. Inscriptions alone reveal over 55 different domestic slave occupations. These included:

- Household Management: Atrienses (porters/hallkeepers), vilici (household managers, often freedmen), dispensatores (stewards), cubicularii (chamberlains).

- Personal Attendants: Ancillae (maids), pedisequi (footmen), vestiarii (valets/dressers), frisores (hairdressers), cosmetae (beauticians), balneatores (bath attendants).

- Food and Drink: Coci (cooks), pistores (bakers), structores (servers), buticularii (cup-bearers), cellarii (pantry keepers), venatores (hunters, for game).

- Childcare and Education: Nutrices (wet nurses), paedagogi (tutors, often highly educated Greeks), ancillae (nannies).

- Maintenance: Cleaners, gardeners, stable hands.

- Economic Impact:

- Enabling Elite Lifestyle: Domestic slaves freed up the Roman elite entirely from manual labor and mundane tasks, allowing them to pursue politics, military careers, intellectual pursuits, and social engagements. This leisure was a cornerstone of their social and economic power.

- Symbol of Wealth: The number and specialization of household slaves directly reflected an owner’s wealth and social standing. It was a visible display of economic power.

- Investment: Highly skilled or educated domestic slaves (e.g., doctors, accountants, tutors, cooks) were expensive to acquire but considered valuable investments, as their skills directly contributed to the owner’s prestige, health, and often even their business affairs.

- Internal Household Economy: Large households often had their own internal economies, with slaves producing goods (like textiles or preserved foods) for the household’s consumption or for sale.

- Urban Services: Fueling City Life

Slaves were critical to the functioning of Roman cities, providing a vast range of services that underpinned daily life and commerce.

- Public Services:

- City Administration: Educated public slaves (owned by the state) worked as clerks, scribes, accountants, and administrators in various government offices, keeping the complex Roman bureaucracy running.

- Public Works: Slaves were employed in maintaining public infrastructure like sewers, aqueducts, baths, and roads within urban areas. They cleaned public buildings, hauled materials, and performed general labor.

- Fire Brigades: Some public slaves served in fire brigades, though these were often supplemented by free labor.

- Commerce and Trade:

- Shopkeepers and Assistants: Many shops (tabernae) in Roman cities were run by slaves on behalf of their masters. These could be small stalls selling everyday goods (bread, wine, oil) or more specialized stores (perfume, clothes, jewelry).

- Banking and Finance: Highly trusted and educated slaves or freedmen managed financial affairs, acted as accountants (rationarii), and even functioned as bankers or agents for their owners in complex business transactions.

- Transportation: Slaves worked as porters in markets and ports, loading and unloading goods, and as litter-bearers for the wealthy.

- Entertainment and Arts:

- Entertainers: Actors, musicians, dancers, and gladiators were often slaves, providing entertainment for the Roman populace.

- Artists and Craftsmen: As mentioned in manufacturing, skilled slaves worked in urban workshops producing goods, from fine pottery and mosaics to jewelry and specialized clothing.

- Professions:

- Physicians: Many doctors in Rome, particularly early on, were slaves or freedmen, often of Greek origin. They provided medical care to their masters’ households and sometimes to the public.

- Teachers/Educators: Slaves, especially educated Greeks, served as tutors for Roman children, teaching them language, rhetoric, philosophy, and other subjects.

- Librarians and Scribes: Slaves copied books and managed libraries for private individuals and public institutions.

- Economic Dynamics and Peculium:

- Peculium: A significant economic mechanism that applied heavily to skilled domestic and urban slaves was the peculium. This was a sum of money or property that a master allowed a slave to manage as their own. While legally belonging to the master, it allowed the slave to engage in small businesses, save money, and even purchase their own freedom. This incentivized slaves to work harder and more efficiently.

- Manumission and Freedmen: The relatively common practice of manumission meant that many urban slaves, particularly those with skills or who managed businesses, could eventually gain their freedom (liberti). Freedmen often continued to work in the same trades or for their former masters (now their patrons), forming a crucial segment of Rome’s urban economy and social fabric. This dynamic allowed for social mobility not typically seen in other slave systems.

In essence, domestic and urban slaves were not just a luxury; they were an integral, active, and highly diverse part of the Roman economy. They enabled the elite lifestyle, provided essential services for city life, and contributed to the flow of goods and wealth, shaping the unique social and economic landscape of the Roman Empire.

Roman Slaves’ Economics: Public Works and State Administration (Servi Publici)

Roman public works and state administration were monumental undertakings that were fundamental to the functioning and expansion of the Roman Empire. Public slaves (servi publici) played a critical and often overlooked role in these sectors, providing a stable, readily available, and technically diverse workforce.

Understanding Servi Publici

Servi publici were slaves owned by the Roman state (the “Roman people” or populus Romanus) or by municipalities, rather than by private citizens or the emperor (imperial slaves). Their roles and economic impact were distinct:

- Public Works (Infrastructure and Maintenance):

- Construction: While large-scale public works projects often relied on a combination of free labor, military engineers, and private contractors who then employed their own slaves, servi publici were also directly employed by the state in the construction and maintenance of critical infrastructure.

- Aqueducts: A prime example is the maintenance of Rome’s extensive aqueduct system. Historical sources indicate that hundreds of public slaves were dedicated to inspecting, repairing, and cleaning the aqueducts to ensure a continuous water supply to the city. This was a vital service for public health and urban life.

- Roads and Bridges: Public slaves contributed to the construction and upkeep of the vast network of Roman roads and bridges that facilitated trade, military movement, and communication across the empire.

- Public Buildings: They were involved in the construction and repair of temples, basilicas, theaters, amphitheatres (like the Colosseum), baths, and other monumental public structures.

- Sewers and Drainage: Maintenance of Rome’s complex sewer system, including the Cloaca Maxima, also fell to public slaves.

- Economic Impact:

- Cost Efficiency: For the state, employing servi publici was an incredibly cost-effective way to manage vast infrastructure. Instead of paying wages to large numbers of free laborers, the state incurred only the costs of acquiring and maintaining the slaves.

- Stable Workforce: Unlike free labor, which might fluctuate with agricultural seasons or economic conditions, servi publici provided a dedicated and relatively stable workforce for long-term projects and continuous maintenance.

- Expertise Retention: Over time, public slaves working on specific projects (e.g., aqueducts) would develop specialized knowledge and skills, ensuring continuity and expertise in complex technical areas. This helped preserve institutional knowledge.

- Facilitating Trade and Administration: The well-maintained infrastructure (roads, ports, water supply) that public slaves helped build and maintain was essential for economic activity across the empire, facilitating trade, communication, and the efficient administration of conquered territories.

- State Administration (Bureaucracy and Services):

- Clerical and Administrative Roles: Public slaves, particularly those who were literate or educated, filled a wide array of administrative and clerical positions within the Roman bureaucracy:

- Scribes and Secretaries: They copied documents, maintained records, and acted as scribes for magistrates, senators, and various government departments.

- Accountants and Treasurers: Public slaves managed public funds, kept financial records, and assisted in tax collection.

- Custodians and Messengers: They served as custodians of public buildings, temples, and archives, and as messengers carrying official communications.

- Assistants to Magistrates and Priests: They provided essential support services to public officials, assisting them in their duties.

- Urban Management: In cities, servi publici performed various municipal functions:

- Market Supervision: Assisting aediles in regulating markets and maintaining order.

- Policing/Firefighting: Some public slaves were involved in urban policing or fire brigades, especially in the later empire.

- Executioners/Lictors’ Attendants: Less desirable, but necessary, public slaves served as executioners or assisted lictors in their duties.

- Economic Impact:

- Efficiency of Bureaucracy: The presence of a large, skilled public slave workforce allowed the Roman state to run its complex administration with remarkable efficiency and continuity, especially given the rapid turnover of elected magistrates.

- Information Management: Their work in record-keeping, copying, and archiving was fundamental to the state’s ability to govern, collect taxes, manage legal disputes, and track resources across an expansive empire.

- Low Administrative Costs: Again, the lack of wages for these administrative roles significantly reduced the overheads of state governance.

- Public Service Delivery: They were the human engine behind many public services, from ensuring clean water to maintaining legal records.

Status and Conditions of Servi Publici

- Generally Higher Status: While still slaves, servi publici often enjoyed a higher status and better conditions than many privately owned slaves (especially those in mines or agriculture).

- They were owned by the collective “Roman people,” which could afford to provide better living conditions.

- Their work was often more skilled, less physically brutal, and more prestigious.

- They might have had more autonomy, better housing, and even a greater chance of manumission.

- They could accumulate peculium and sometimes even partner with freeborn or freed women.

- Incentives: The possibility of manumission and a more stable, often skilled, working environment provided incentives for loyalty and efficiency. Once freed, these liberti publici could continue to serve the state or enter the free urban labor market.

In conclusion, servi publici were an integral and highly valuable economic asset for the Roman state. Their widespread employment in public works and state administration provided a stable, low-cost, and often skilled workforce that enabled the construction and maintenance of Rome’s iconic infrastructure, supported its vast bureaucracy, and ultimately contributed significantly to the economic power and longevity of the Roman Empire.

Roman Slaves’ Economics: Trade and Commerce

Roman slaves were not merely laborers in fields or mines; they were deeply integrated into the sophisticated and diverse economy of Roman trade and commerce. Their involvement ranged from manual labor in warehouses and ports to highly skilled and entrepreneurial roles, reflecting the unique fluidity of Roman slavery and its emphasis on maximizing economic utility.

Here’s a breakdown of their economic impact on trade and commerce:

- Transportation and Logistics:

- Porters and Haulers: Slaves were the primary muscle for loading and unloading ships in major ports like Ostia (Rome’s port) and Puteoli, as well as barges on rivers. They hauled goods through city streets, moved merchandise in and out of warehouses (horrea), and transported commodities to market.

- Naval Labor: While not solely slave-driven, slaves served as rowers on merchant ships (especially galleys) and performed general labor on trading vessels.

- Litter-Bearers: For the wealthy, slaves acted as litter-bearers, transporting their masters and often accompanying them on business dealings, which might involve carrying documents or samples.

- Retail and Shopkeeping (Tabernae):

- Manning Shops: A significant number of shops (tabernae) in Roman cities were operated by slaves on behalf of their masters. These ranged from bakeries, butchers, and fishmongers to shops selling textiles, perfumes, and even luxury goods.

- Sales and Customer Service: Slaves interacted directly with customers, selling goods, handling money, and sometimes even managing the inventory. They were the public face of many Roman commercial enterprises.

- Specialized Trades: Many urban slaves were skilled artisans (as mentioned previously) who produced the goods they then sold in their masters’ shops, such as shoemakers, jewelers, or potters.

- Management and Finance (Business Agents):

- Vilici and Procuratores: Highly trusted and often educated slaves or freedmen (those who had been manumitted) acted as managers (vilici for estates, procuratores for larger enterprises) for their owners’ businesses. They oversaw operations, managed other slaves, handled accounts, and made daily business decisions.

- Bankers and Accountants (Argentarii and Rationarii): Educated slaves and freedmen played crucial roles in Roman finance. They kept ledgers, managed financial records (rationarii), and sometimes acted as informal bankers (argentarii), managing deposits, making loans, and facilitating transactions on behalf of their masters. This was a sector where literacy and numeracy were highly valued.

- International Trade Agents: For elite Romans (particularly senators) who were legally restricted from engaging directly in commerce, slaves or freedmen often acted as their business agents, conducting trade and investments on their behalf across the empire. This allowed the elite to profit from commerce while maintaining their aristocratic image.

- The Peculium System and Its Economic Impact:

- Incentive for Entrepreneurship: The peculium was a fund of money or property that a master would allow a slave to manage as if it were their own. While legally still the master’s property, the slave had considerable de facto control over it.

- Operating Businesses: Slaves could use their peculium as working capital to run their own small businesses or engage in trade. Any profits they made, beyond a portion perhaps remitted to the master, could be added to their peculium.

- Pathway to Freedom: The peculium was a powerful economic incentive. A successful slave could accumulate enough funds in their peculium to eventually purchase their own freedom (manumission). This made slaves active participants in the economic system with a direct stake in their own productivity and profitability.

- Limited Liability (Proto-LLC): Some scholars even see the peculium as a proto-form of a limited liability concept. If a slave incurred debts in business, the master’s liability was often limited to the value of the peculium, protecting the master’s other assets. This encouraged masters to allow slaves to engage in more adventurous commercial ventures.

- The Slave Trade Itself:

- Lucrative Industry: The acquisition and sale of slaves was a significant industry in itself. Slave traders (mangones) operated throughout the empire, with major slave markets (e.g., Delos). The trade generated immense wealth for those involved, facilitated by Roman conquests and piracy.

Economic Consequences:

- Efficiency and Scale: The widespread use of slaves in trade and commerce, particularly the highly skilled and motivated ones operating with peculium, significantly contributed to the efficiency and scale of Roman economic activity. It allowed for complex commercial networks to function with relatively low labor costs.

- Social Mobility (for Freedmen): The possibility of manumission through commercial success allowed a degree of social mobility for some slaves. Freedmen often continued in their trades, becoming successful businessmen or professionals who maintained strong patronage ties with their former masters.

- Concentration of Wealth: Ultimately, the profits generated by slave labor in commerce flowed upwards to the slave-owning elite, reinforcing their economic and social dominance.

In conclusion, Roman slaves were far more than just manual laborers in trade and commerce. They were vital components of the Roman commercial engine, serving as skilled artisans, shopkeepers, managers, bankers, and even independent (though legally dependent) entrepreneurs, all facilitated by the unique Roman system of peculium and the possibility of manumission. Their multifaceted contributions were indispensable to the vast and complex economic networks of the Roman Empire.

Roman Slaves’ Economics: Educated and Skilled Professions

While the most common image of Roman slaves is often of those toiling in fields or mines, the Roman economy also relied heavily on a vast array of educated and skilled slaves who performed specialized professional and craft duties. These individuals represented a highly valuable economic asset for their owners and contributed significantly to the complexity and functioning of Roman society.