Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821)

The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries, 1812

(Wiki Image By Jacques-Louis David – zQEbF0AA9NhCXQ at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22174172)

Napoleon Quotes

Here are some notable quotes attributed to Napoleon Bonaparte, reflecting his military philosophy, political ambition, and views on leadership:

- “Impossible is a word to be found only in the dictionary of fools.”

- Context: Reflects his belief in overcoming obstacles and his boundless ambition.

- “Victory belongs to the most persevering.”

- Context: Highlights his emphasis on tenacity and endurance in warfare and life.

- “A leader is a dealer in hope.”

- Context: A profound observation on the psychological aspect of leadership and inspiring followers.

- “If you want a thing done well, do it yourself.”

- Context: Shows his characteristic hands-on approach and attention to detail.

- “The world suffers a lot. Not because of the violence of bad people, but because of the silence of good people.”

- Context: A more philosophical and less commonly attributed quote, but it speaks to a sense of responsibility.

- “History is a set of lies agreed upon.”

- Context: A cynical view on how history is written and shaped by the victors or those in power.

- “Take time to deliberate, but when the time for action has arrived, stop thinking and go in.”

- Context: Emphasizes decisiveness and the importance of action once a plan is set.

- “Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake.”

- Context: A classic military maxim, highlighting strategic patience and opportunism.

- “Religion is excellent stuff for keeping common people quiet.”

- Context: Reveals his pragmatic and utilitarian view of religion as a tool for social control.

- “Power is my mistress. I have worked too hard to conquer her, and I will not allow anyone to take her from me.”

- Context: A stark declaration of his driving ambition and desire for absolute control.

- “The bullet that will kill me is not yet cast.”

- Context: Reflects his immense self-confidence and belief in his destiny.

- “To understand the man, you have to know what was happening in the world when he was twenty.”

- Context: A reflective insight into the formative influence of historical events on an individual, particularly relevant to his own life during the French Revolution.

- “Circumstances? I make circumstances.”

- Context: Underscores his belief in his own agency and ability to shape events through will and action.

- “There are but two powers in the world, the sword and the mind. In the long run, the sword is always conquered by the mind.”

- Context: A surprising quote from a military leader, suggesting an ultimate appreciation for intellectual power over brute force, though he wielded both.

- “From the sublime to the ridiculous is but a step.”

- Context: A sober reflection on the unpredictable nature of fortune, often quoted regarding the collapse of his Russian campaign.

These quotes paint a picture of a complex figure driven by a relentless will, strategic brilliance, and an acute understanding of human nature.

Napoleon YouTube Video

- The Rise Of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte | History Hit | Timeline by Timeline – World History Documentaries

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uC8TK7GH85o

- Views: 2,419,803

- Napoleon – Path to Power (All Parts) by Epic History

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BARSrLpQ9VU

- Views: 656,089

- Historian Breaks Down Napoleon’s Battle Tactics | WIRED by WIRED

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=56uJd9AqMFA

- Views: 436,385

- Napoleon’s Italian Campaign (All Parts) by Epic History

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bm1RhjcdJek

- Views: 2,773,563

- The Rise & Fall Of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte | The Man Who Would Rule Europe | Timeline by Timeline – World History Documentaries

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U0vPCPnm59c

- Views: 706,797

Napoleon YouTube Video Movie

- NAPOLEON – Official Trailer (HD) by Sony Pictures Entertainment

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OAZWXUkrjPc

- Views: 38,093,408

- NAPOLEON – Official Trailer #2 (HD) by Sony Pictures Entertainment

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LIsfMO5Jd_w

- Views: 22,032,789

Napoleon YouTube Video TV

- Napoleon PBS Documentary 1 Of 4 by Prince Corsica

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MrbiSUgZEbg

- Views: 3,718,317

- The Rise Of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte | History Hit | Timeline by Timeline – World History Documentaries

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uC8TK7GH85o

- Views: 2,420,305

- Napoleon – Path to Power (All Parts) by Epic History

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BARSrLpQ9VU

- Views: 657,585

- Napoleonic Wars 1804 – 1814 (All Parts) by Epic History

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E9VfahNloQA

- Views: 1,248,561

- Napoleon Bonaparte – The Ultimate Saga Documentary by The People Profiles

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tly8ArghRV8

- Views: 243,800

You may also be interested in these clips from the 2002 TV miniseries Napoléon:

- Napoléon with Talleyrand, discussing French peace terms, post-Austerlitz, 1805 by Rick Davi

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7NFQ9XCmVdw

- Views: 37,417

- Napoléon ~Battle of Austerlitz (English) HD by Chancellor of Preußen

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AotbMs7BIhE

- Views: 855,573

- Napoléon ~Napoleon’s encounter with Marshal Ney (English) HD by Chancellor of Preußen

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=puZh2LARvHU

- Views: 811,205

- Napoléon and Metternich (Napoléon 2002) by Klemens von Metternich

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uOxK-7Vsi4E

- Views: 100,374

Napoleon Books

For a single, all-encompassing book on Napoleon, the best modern choice is “Napoleon: A Life” by Andrew Roberts.

The literature on Napoleon is vast, but a few key books stand out for their scholarship, readability, and perspective. Here are some of the most highly regarded options for various interests.

The Definitive Modern Biography 👑

“Napoleon: A Life” by Andrew Roberts

This is widely considered the best single-volume biography of Napoleon. Roberts uses new archival research, including Napoleon’s massive collection of letters, to present a detailed, engaging, and largely sympathetic portrait of his subject. It masterfully balances the personal, political, and military aspects of Napoleon’s life. If you are going to read just one book, this is the one.

The Classic Character Study

“Napoleon Bonaparte: An Intimate Biography” by Vincent Cronin

Published in 1971, this is an older but beautifully written biography that focuses less on the minute details of battles and more on Napoleon the man. Cronin delves into his personality, his relationships with women, his intellectual interests, and the motivations that drove him. It’s an excellent choice for readers who want to understand Napoleon’s character.

The Essential Military History ⚔️

“The Campaigns of Napoleon” by David G. Chandler

This is the undisputed magnum opus of Napoleonic military history. It is a massive, authoritative, and incredibly detailed account of every major campaign Napoleon fought. While perhaps too dense for a casual reader, it is the essential, indispensable work for anyone serious about understanding Napoleon’s genius as a commander.

For a Contrasting, Critical View

“Napoleon: The Man Behind the Myth” by Adam Zamoyski

This biography serves as an excellent counterpoint to Andrew Roberts’ more favorable view. Zamoyski presents a more skeptical and critical portrait, portraying Napoleon not as a visionary leader but as an opportunistic dictator whose ambition led to endless war and destruction in Europe. It’s a well-researched and compelling argument that challenges the “great man” narrative.

Napoleon Chronology Table

The French Empire at its greatest extent in 1812

(Wiki Image By Alexander Altenhof – Own work. Source of Information: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21366121)

Here’s a chronological table of key events in the life of Napoleon Bonaparte:

| Year/Period | Key Event/Development |

| 1769 | Born Napoleone di Buonaparte in Ajaccio, Corsica (August 15). |

| 1779-1785 | Attends military schools in France (Brienne-le-Château, École Militaire in Paris), specializing in artillery. |

| 1785 | Graduated as a second lieutenant in the Royal Artillery. |

| 1789 | The French Revolution begins; Napoleon supports the revolutionary cause. |

| 1793 | He played a key role in the Siege of Toulon, leading to his promotion to brigadier general. The Bonaparte family flees Corsica. |

| 1795 | Helps suppress a Royalist uprising in Paris (13 Vendémiaire), gaining further recognition. |

| 1796-1797 | Leads the Italian Campaign, achieving stunning victories against Austrians and Sardinians (e.g., Lodi, Arcole, Rivoli). Marries Joséphine de Beauharnais (1796). |

| 1797 | Negotiates the Treaty of Campo Formio, expanding French influence in Italy. |

| 1798-1799 | Leads the Egyptian Campaign; initial land victories (Battle of the Pyramids) followed by naval disaster (Battle of the Nile). Abandons the army and returns to France. |

| 1799 | Orchestrates the Coup of 18 Brumaire (November 9), overthrowing the Directory and becoming First Consul. |

| 1800 | Leads the Second Italian Campaign, securing victory at the Battle of Marengo. |

| 1800 | Establishes the Bank of France (January). |

| 1801 | The Concordat of 1801 was signed with Pope Pius VII, reconciling France with the Catholic Church. |

| 1802 | Signed the Treaty of Amiens (peace with Britain). Declared First Consul for Life via plebiscite. |

| 1804 | Enacts the Napoleonic Code (Code Civil des Français, March). Proclaimed Emperor of the French (May), crowns himself Emperor Napoleon I (December 2). |

| 1805 | Battle of Trafalgar (naval defeat by Nelson, October). Battle of Austerlitz (decisive victory over Austro-Russian forces, December). |

| 1806 | Defeats Prussia at the Battles of Jena-Auerstedt (October). Establishes the Continental System (Berlin Decree, November). |

| 1807 | Defeats Russia at the Battle of Friedland. Signs the Treaties of Tilsit with Tsar Alexander I, marking the peak of his power. |

| 1808 | Begins the Peninsular War in Spain, a costly and draining conflict. |

| 1809 | Defeats Austria at the Battle of Wagram. Divorce Joséphine. |

| 1810 | Marries Marie Louise of Austria (April). |

| 1811 | Birth of his son, Napoleon II, the “King of Rome” (March). |

| 1812 | Launches the disastrous Invasion of Russia. Suffered catastrophic losses during the retreat from Moscow. |

| 1813 | Suffered a decisive defeat at the Battle of Leipzig (Battle of the Nations) against the Sixth Coalition. |

| 1814 | Allied forces invade France. First Abdication (April 6). Exiled to Elba. The Bourbon monarchy was restored. |

| 1815 | Escapes from Elba (March), beginning the “Hundred Days.” Suffers final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo (June 18). Second Abdication (June 22). |

| 1815-1821 | Exiled to Saint Helena, a remote island in the South Atlantic. |

| 1821 | Dies on Saint Helena (May 5). |

Napoleon History

General Bonaparte surrounded by members of the Council of Five Hundred during the Coup of 18 Brumaire, by François Bouchot

(Wiki Image By François Bouchot – www.histoire-image.org (direct link), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=304325)

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; August 15, 1769 – May 5, 1821) was a French military leader and emperor who profoundly shaped European history in the early 19th century. His life was a dramatic ascent from a minor noble family on Corsica to the ruler of a vast empire, leaving an indelible mark on politics, warfare, and society.

Early Life and Military Education (1769-1793)

Napoleon was born in Ajaccio, Corsica, just a year after the island was transferred from Genoa to France. Despite his family’s minor nobility, they were not wealthy. He was the second of eight surviving children of Carlo Buonaparte, a lawyer, and Letizia Ramolino.

At age nine, he moved to mainland France for his education. He attended military colleges at Brienne-le-Château (for five years) and later the prestigious École Militaire in Paris (for one year), specializing in artillery. During his time in Paris, his father died, forcing him to take on more family responsibilities. He graduated in 1785 as a second lieutenant in the Royal Artillery.

The outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789 profoundly influenced his early career. He embraced the revolutionary ideals and, during periods of leave in Corsica, actively promoted the French revolutionary cause. However, a conflict with Corsican nationalist Pasquale Paoli led his family to flee to mainland France in 1793.

Rise to Prominence (1793-1799)

Back in France, Napoleon’s military career rapidly accelerated:

- Siege of Toulon (1793): His first major breakthrough came during the Siege of Toulon. His innovative artillery tactics were crucial in expelling British and Royalist forces from the port city. This success brought him to the attention of powerful Jacobin figures and earned him a promotion to brigadier general at just 24.

- Italian Campaign (1796-1797): Appointed commander of the French Army of Italy, Napoleon transformed a dispirited force into a formidable army. He led a series of stunning victories against the Austrians and Sardinians, demonstrating his tactical genius (e.g., Battle of Lodi, Battle of Arcole, Battle of Rivoli). His campaigns forced Austria to sign the Treaty of Campo Formio (1797), expanding French influence significantly. He established a reputation for swift, decisive action: “Bonaparte flies like lightning and strikes like thunder.”

- Egyptian Campaign (1798-1799): Seeking to disrupt British trade routes to India, Napoleon led an expedition to Egypt. While he achieved land victories (e.g., Battle of the Pyramids), the French fleet was destroyed by Admiral Horatio Nelson at the Battle of the Nile (1798), effectively stranding his army. Despite this, he launched scientific expeditions, leading to works like “La Description de l’Egypte.” Receiving news of political turmoil in France, he secretly abandoned his army and returned to Paris.

First Consul and Consolidation of Power (1799-1804)

Capitalizing on the Directory’s instability and unpopularity, Napoleon seized political power in a coup d’état on 18 Brumaire (November 9, 1799). The Directory was replaced by a three-member Consulate, with Napoleon as the First Consul, quickly becoming the dominant figure.

During this period, he focused on stabilizing and reforming France after a decade of revolutionary chaos:

- Napoleonic Code (1804): His most enduring legacy, this comprehensive civil code systematized French law, establishing principles like equality before the law, abolition of feudalism, and religious freedom. It remains the foundation of French civil law and influenced legal systems worldwide.

- Concordat of 1801: He negotiated an agreement with Pope Pius VII, reconciling France with the Catholic Church and restoring religious peace after the Revolution’s anti-clerical policies.

- Bank of France (1800): Established to stabilize national finances and currency.

- Centralized Administration: He created a highly efficient and centralized bureaucracy, laying the groundwork for modern French administration.

- Education System: Initiated reforms to the French educational system.

- Peace of Amiens (1802): A temporary peace treaty with Britain, bringing a brief lull to the European wars.

Emperor of the French (1804-1814)

In May 1804, Napoleon was proclaimed Emperor of the French. On December 2, 1804, he crowned himself Emperor Napoleon I in Notre Dame Cathedral, solidifying his absolute rule and establishing a new imperial dynasty.

- Napoleonic Wars: His reign was dominated by a series of major conflicts against various European coalitions.

- Master of Europe: Napoleon’s Grande Armée (Great Army) achieved legendary victories, such as Austerlitz (1805), Jena-Auerstedt (1806), and Wagram (1809), leading to French domination over much of continental Europe. He dissolved the Holy Roman Empire and created client states, often placing his family members on their thrones.

- Continental System (1806): Lacking the naval power to defeat Britain directly (especially after the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805), he attempted to cripple its economy through an economic blockade, prohibiting trade with continental Europe. This largely failed and bred resentment.

- Peninsular War (1808-1814): His invasion of Spain ignited a brutal guerrilla war that tied down vast French resources and fueled Spanish nationalism, becoming a significant drain on his empire.

- Divorce and Second Marriage: In 1809, he divorced his beloved Joséphine de Beauharnais as she could not bear him an heir. He married Marie Louise of Austria in 1810, and they had a son, Napoleon II (the King of Rome) in 1811.

- Invasion of Russia (1812): This was the catastrophic turning point. Leading an army of over 600,000, he invaded Russia. Despite reaching Moscow, the harsh Russian winter, scorched-earth tactics, and long supply lines decimated his forces during the retreat. Only a fraction of his army returned.

Decline, Abdication, and Exile (1813-1821)

- War of the Sixth Coalition (1813-1814): Emboldened by the Russian disaster, European powers united against him. He suffered a decisive defeat at the Battle of Leipzig (1813), the “Battle of the Nations,” forcing his retreat from Germany.

- First Abdication and Elba (1814): With Allied forces invading France and Paris falling, Napoleon was forced to abdicate on April 6, 1814. He was exiled to the small island of Elba in the Mediterranean.

- The Hundred Days (1815): In March 1815, Napoleon famously escaped Elba and returned to France, rallying supporters and briefly regaining power for about 100 days.

- Battle of Waterloo (1815): His final campaign ended in a crushing defeat at the Battle of Waterloo on June 18, 1815, against a combined Anglo-Allied army under the Duke of Wellington and a Prussian army under Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher.

- Second Abdication and Saint Helena: After Waterloo, Napoleon abdicated again and was exiled to the remote British island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic, where he remained under guard.

- Death (1821): Napoleon died on Saint Helena on May 5, 1821, at the age of 51, likely from stomach cancer.

Napoleon’s legacy is complex and profound. He transformed France and Europe through his military conquests, legal reforms (most notably the Napoleonic Code), and administrative innovations, laying the groundwork for modern nation-states and influencing warfare for generations.

Napoleon: Early Life and Military Education (1769-1792)

Bonaparte, aged 23, was a lieutenant-colonel of a battalion of Corsican Republican volunteers. Portrait made in 1835 by Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux

(Wiki Image By Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux – Transferred from de.wikipedia to Commons by Stefan Bernd.Alt source: [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5556134)

Napoleon Bonaparte’s early life and military education (1769-1792) were shaped by his Corsican origins and a rigorous French military schooling that prepared him for the turbulent years of the French Revolution.

Early Life (1769-1784)

Napoleon was born Napoleone di Buonaparte on August 15, 1769, in Ajaccio, Corsica. This was just a year after the Republic of Genoa had formally ceded the island to France. His family belonged to the minor Corsican nobility of Italian descent, but they were not particularly wealthy. His father, Carlo Buonaparte, was a lawyer and a representative of Corsica at the court of King Louis XVI, while his mother, Letizia Ramolino, was a strong-willed figure who would later instill resilience in her children. Napoleon was the second of eight surviving children. Growing up in Corsica, he initially identified more with his native Corsican heritage than with the French, and Corsican was his first language.

Military Education in France (1784-1792)

At the age of nine, Napoleon was sent to mainland France for education, a common practice for children of the minor nobility.

- Brienne-le-Château (1779-1784): He attended the royal military school at Brienne-le-Château. Here, he focused on academic subjects, showing a particular aptitude for mathematics, geography, and history. He was often a solitary figure, sometimes mocked for his Corsican accent and humble background, which likely fueled his ambition and intense focus.

- École Militaire, Paris (1784-1785): In 1784, he gained admission to the prestigious École Militaire in Paris, a premier military academy for future officers. He chose to specialize in artillery, a highly technical branch that was gaining importance in modern warfare and appealed to his mathematical skills. During his time here, his father died, forcing him to complete the two-year course in just one year to take on family responsibilities. He graduated as a second lieutenant in the Royal Artillery in 1785, at the age of 16.

From 1785 to 1792, Napoleon served in various garrisons in France, including Valence and Auxonne. This period saw him studying military strategy, history, and the works of Enlightenment thinkers like Rousseau and Voltaire. He spent much of his time in Corsica during leaves, becoming involved in the island’s politics, initially aligning with Corsican nationalists but eventually siding more strongly with the French revolutionary cause. However, a conflict with Corsican nationalist Pasquale Paoli led his family to flee permanently to mainland France in 1793, marking a decisive break with his Corsican identity and fully embracing his French military career just as the Revolution was escalating into radicalism.

Napoleon: Rise to Prominence (1793-1798)

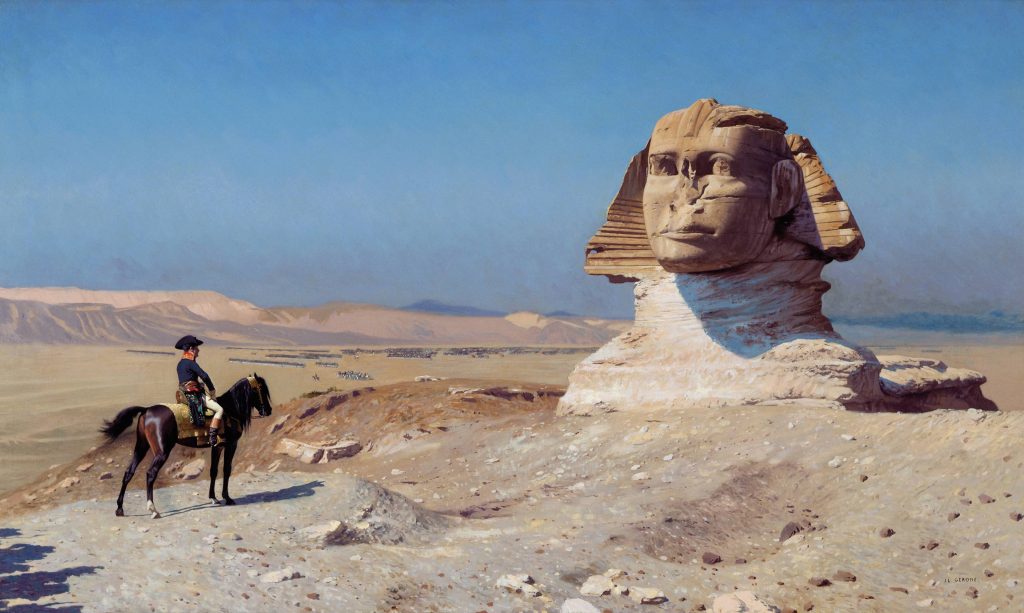

Bonaparte Before the Sphinx (c. 1886) by Jean-Léon Gérôme, Hearst Castle

(Wiki Image By Jean-Léon Gérôme – Fuente, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75309705)

Napoleon’s rise to prominence between 1793 and 1798 was meteoric, propelled by his military genius during the turbulent French Revolutionary Wars. This period saw him transform from an obscure artillery officer into France’s most celebrated general.

Siege of Toulon (1793) 🇫🇷

Napoleon’s first major breakthrough came during the Siege of Toulon in 1793. Toulon, a major French naval base, had revolted against the radical French Republic and was occupied by British, Spanish, and Royalist forces. As an artillery officer, Napoleon recognized the strategic importance of capturing the high ground overlooking the harbor. His innovative and aggressive deployment of artillery played a crucial role in forcing the Allied evacuation. This success brought him to the attention of powerful figures within the revolutionary government, including Augustin Robespierre (Maximilien’s younger brother), and led to his promotion to brigadier general at just 24 years old.

Italian Campaign (1796-1797) 🇮🇹

After a brief period of arrest following the Thermidorian Reaction (the fall of Robespierre), Napoleon’s career was revived when he helped suppress a Royalist uprising in Paris in 1795. This earned him command of the French Army of Italy in 1796. This campaign cemented his reputation as a military genius:

- Transforming the Army: He took command of a poorly equipped and demoralized army. Through sheer charisma, inspiring speeches, and promises of glory and plunder, he transformed it into a formidable fighting force.

- Rapid Victories: Napoleon launched a series of lightning campaigns against the Austrian and Sardinian forces in Northern Italy. He employed innovative tactics, emphasizing speed of maneuver, concentrated attacks, and living off the land, often defeating larger armies by striking their forces individually. Key victories included Lodi, Arcole, and Rivoli.

- Strategic Outcome: His stunning successes forced Sardinia to make peace and compelled Austria to sign the Treaty of Campo Formio (1797). This treaty expanded French influence significantly in Italy and the Rhineland, reshaping the map of Europe. Napoleon demonstrated a mastery of both military and diplomatic strategy, negotiating treaties independently and establishing client republics in Italy. His reputation as a decisive and brilliant commander became legendary across Europe: “Bonaparte flies like lightning and strikes like thunder.”

Egyptian Campaign (1798) 🇪🇬

Having effectively concluded the Italian Campaign, Napoleon persuaded the Directory (France’s governing body) to approve an expedition to Egypt in 1798. The primary goal was to disrupt British trade routes to India and potentially open a path to British colonial possessions, rather than any direct French colonial interest in Egypt itself.

- Military Successes (Land): Napoleon achieved initial successes on land, notably the Battle of the Pyramids (July 1798), where his disciplined forces decisively defeated the Mamluk cavalry. He then occupied Cairo.

- Naval Disaster: However, the French fleet supporting the expedition was catastrophically defeated by Admiral Horatio Nelson’s British fleet at the Battle of the Nile (August 1798). This trapped Napoleon’s army in Egypt, cutting off their supply lines and reinforcements.

- Exploration and Propaganda: Despite the strategic setback, the campaign had significant cultural and scientific repercussions. Napoleon brought a large contingent of scholars and scientists, leading to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone and the monumental “Description de l’Égypte,” which greatly advanced European knowledge of ancient Egypt. He skillfully managed the narrative back in France, maintaining his image as a hero despite the challenging military situation.

Though the Egyptian Campaign ultimately failed in its strategic objectives, it solidified Napoleon’s reputation as a daring and ambitious general, setting the stage for his return to France and subsequent seizure of political power.

Napoleon: First Consul and Consolidation of Power (1799-1804)

Bonaparte, First Consul, by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Posing the hand inside the waistcoat was often used in portraits of rulers to indicate calm and stable leadership.

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – njn.net, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6107787)

Following his return from the Egyptian Campaign, Napoleon Bonaparte seized political power in France, quickly transitioning from a military general to the nation’s supreme leader during the period of the First Consulship (1799-1804). This era was marked by a vigorous consolidation of power and a series of wide-ranging reforms that brought stability to post-revolutionary France.

The Coup of 18 Brumaire (November 9, 1799) 🇫🇷

Capitalizing on the instability, corruption, and unpopularity of the Directory (France’s five-man governing body), Napoleon orchestrated a bloodless coup d’état on 18 Brumaire (November 9, 1799). With the support of influential figures like Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès and his brother Lucien Bonaparte, Napoleon used military force to disperse the legislative councils. The Directory was overthrown, and a new government, the Consulate, was established.

Initially, the Consulate was designed with three consuls, but Napoleon quickly emerged as the dominant figure. He was appointed First Consul for a term of ten years (soon after made for life), effectively becoming the most powerful individual in France. This marked the de facto end of the French Revolution and the beginning of Napoleon’s autocratic rule.

Consolidation of Power

Napoleon swiftly moved to centralize authority and legitimize his new regime:

- New Constitution (Year VIII): A new constitution, largely drafted by Napoleon, was quickly enacted. While it maintained the illusion of a republic, it concentrated real power in the hands of the First Consul, granting him extensive executive authority.

- Abolition of Local Assemblies: He replaced elected local assemblies with centrally appointed prefects in each department, ensuring direct control from Paris and creating a highly efficient, top-down administrative system.

- Plebiscite for Legitimacy: Napoleon frequently used plebiscites (popular votes) to approve his constitutional changes and extensions of power. While often manipulated, these votes gave his regime a veneer of popular consent, distinguishing it from the absolute monarchies he opposed.

Major Domestic Reforms

During his time as First Consul, Napoleon embarked on a period of intense and fundamental reforms that brought much-needed order and stability to France after a decade of revolutionary turmoil:

- The Napoleonic Code (Code Civil des Français – 1804): This is arguably Napoleon’s most enduring and influential legacy. It was a comprehensive and standardized legal code that replaced a patchwork of diverse and often confusing regional laws. It codified many principles of the French Revolution, such as equality before the law, the abolition of feudalism, and religious freedom. While progressive in many aspects, it also reinforced patriarchal authority within the family and notably re-established colonial slavery. Its clarity, logic, and uniformity made it a model for civil law systems worldwide.

- Concordat of 1801: Recognizing the political utility of reconciling with the Catholic Church, Napoleon negotiated an agreement with Pope Pius VII. This Concordat formally acknowledged Catholicism as the religion of the majority of French citizens, restored some of the Church’s civil status, and ended a decade of anti-clerical policies. In return, the Pope recognized the French Republic and accepted the loss of Church lands confiscated during the Revolution. While bringing religious peace, Napoleon maintained state control over the Church.

- Bank of France (1800): To stabilize the national finances and restore economic confidence, Napoleon established the Bank of France. This central bank was granted the exclusive privilege of issuing a unified national currency (the franc germinal, based on both gold and silver), managed government finances, and provided credit. This laid the groundwork for modern central banking in France.

- Educational Reforms: Napoleon initiated reforms to the French educational system, emphasizing meritocracy and the training of competent administrators and military officers. He established lycées (secondary schools) to provide standardized education.

- Public Works: He invested in various public works projects, including roads, canals, and monuments, which helped create employment and improve infrastructure.

Peace and Preparation for Empire

- Peace of Amiens (1802): Napoleon secured a temporary peace with Great Britain through the Treaty of Amiens. This brought a brief respite from the European wars, allowing him to focus more intently on internal reforms.

- Consul for Life (1802): His immense popularity and success led to a plebiscite in 1802 that confirmed him as First Consul for Life.

- As war with Britain again loomed in 1803, Bonaparte realized that his American colony of Louisiana would be difficult to defend. In need of funds, he agreed to the Louisiana Purchase with the United States, doubling the latter’s size. The price was $15 million.

- Preparation for Empire: By 1804, Napoleon had effectively transformed France into a centralized, authoritarian state under his personal control. The final step was to formalize this power, which he did by declaring himself Emperor, a move approved by another plebiscite, thus ending the First Consulship and ushering in the First French Empire.

Napoleon: Emperor of the French Napoleonic Wars (1805-1808)

The Treaties of Tilsit: Napoleon meeting with Alexander I of Russia on a raft in the middle of the Neman River, 7 July 1807

(Wiki Image By Adolphe Roehn – histoire-image.org, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1370024)

The period from 1805 to 1808 saw Napoleon’s power as Emperor of the French reach its zenith through a series of stunning military victories and strategic maneuvers that profoundly reshaped the map of Europe. This era was dominated by the War of the Third Coalition and the War of the Fourth Coalition, along with the expansion of the Continental System and the beginning of the draining Peninsular War.

War of the Third Coalition (1805)

This coalition was formed in response to Napoleon’s aggressive policies, particularly his expansion in Italy and Germany. It consisted primarily of Great Britain, Austria, and Russia.

- Ulm Campaign (September-October 1805): Napoleon’s Grande Armée executed a brilliant flanking maneuver, rapidly marching across Germany and encircling a large Austrian army under General Mack at Ulm. The Austrian forces were forced to surrender at Ulm without a major pitched battle, a stunning strategic victory for Napoleon.

- Battle of Trafalgar (October 21, 1805): While Napoleon’s land forces were dominant, the British Royal Navy, under Admiral Horatio Nelson, delivered a decisive blow to the combined French and Spanish fleets off the coast of Spain. This crushing British victory secured naval supremacy for Great Britain for the remainder of the Napoleonic Wars and effectively ended any realistic French threat of invading the British Isles.

- Battle of Austerlitz (December 2, 1805): Often regarded as Napoleon’s greatest masterpiece, this battle saw him decisively defeat a combined Austro-Russian army (the “Battle of the Three Emperors”) in Moravia (modern-day Czech Republic). Napoleon lured the Allied forces into attacking his right flank, then launched a surprise attack through their center, shattering their lines.

- Treaty of Pressburg (December 1805): Following Austerlitz, Austria was forced to sign this harsh treaty, ceding significant territories to France and its allies (especially Bavaria and Württemberg), and effectively dissolving the Third Coalition. This solidified Napoleon’s control over Central Europe.

- Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire (1806): As a direct consequence of Austerlitz and Pressburg, Napoleon dissolved the ancient Holy Roman Empire and created the Confederation of the Rhine, a league of German states allied with and dominated by France.

War of the Fourth Coalition (1806-1807)

Prussia, feeling its influence threatened by Napoleon’s consolidation of German states, along with Russia, Saxony, Sweden, and Great Britain, formed the Fourth Coalition.

- Battles of Jena-Auerstedt (October 14, 1806): In a swift and devastating campaign, Napoleon inflicted a crushing defeat on the Prussian army in twin battles. Napoleon personally commanded at Jena, while Marshal Davout achieved a stunning victory against the main Prussian army at Auerstedt. This destroyed the Prussian army as an effective fighting force and led to the French occupation of Berlin.

- Battle of Eylau (February 1807): A bloody and indecisive battle fought against the Russians in East Prussia during a harsh winter. Both sides suffered heavy casualties, and it was a rare moment where Napoleon did not achieve a clear victory.

- Battle of Friedland (June 14, 1807): Napoleon decisively defeated the Russian army. This victory compelled Tsar Alexander I to seek peace.

- Treaties of Tilsit (July 1807): These treaties, signed by Napoleon and Tsar Alexander I on a raft in the Niemen River, marked the zenith of Napoleon’s power. Russia effectively became an ally, agreeing to join the Continental System and allowing Napoleon a free hand in Western Europe. Prussia was severely punished, losing over half its territory, which was used to create new French client states like the Duchy of Warsaw and the Kingdom of Westphalia.

Expansion of the Continental System

Following his inability to directly invade Britain (due to Trafalgar) and his dominance over continental Europe, Napoleon intensified his economic warfare:

- Berlin Decree (November 1806): Issued after the defeat of Prussia, this decree formally established the Continental System, forbidding all trade between continental Europe and Great Britain.

- Milan Decree (December 1807): Further strengthened the Continental System, declaring that any ship that submitted to British naval inspection or paid British duties would be considered fair game for French seizure. The system was now officially extended to Russia and much of Napoleon’s allied and controlled territories.

Beginning of the Peninsular War (1807-1808)

The enforcement of the Continental System directly led to the costly and draining Peninsular War in the Iberian Peninsula.

- Invasion of Portugal (1807): Napoleon ordered the invasion of Portugal, a long-standing British ally that refused to join the Continental System. French forces under General Junot marched through Spain and occupied Lisbon.

- Intervention in Spain (1808): Napoleon then turned his attention to Spain, a nominal ally. He exploited a power struggle within the Spanish royal family, orchestrating the abdication of King Charles IV and his son Ferdinand VII, and installing his own brother, Joseph Bonaparte, as King of Spain in May 1808.

- Dos de Mayo Uprising (May 2, 1808): This cynical act sparked a massive and widespread popular uprising against the French occupation in Madrid, known as the Dos de Mayo uprising. This quickly ignited the Peninsular War, a brutal guerrilla conflict that would tie down vast numbers of French troops, drain Napoleon’s resources, and become a significant factor in his eventual downfall.

By the end of 1808, Napoleon stood as the undisputed master of most of continental Europe. Still, the seeds of prolonged resistance in Spain and the inherent weaknesses of the Continental System were already becoming apparent.

Napoleon: Emperor of the French Invasion of Russia (1809-1812)

Napoleon watching the fire of Moscow in September 1812, by Adam Albrecht (1841)

(Wiki Image By Albrecht Adam – скан из книги, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35260478)

The period between 1809 and 1812 represents the peak of Napoleon’s territorial control and dynastic consolidation, immediately preceding the catastrophic invasion of Russia that would mark the beginning of his decline.

War of the Fifth Coalition (1809)

Though Napoleon had dominated Europe after Tilsit, Austria, emboldened by French difficulties in the Peninsular War, sought to reverse its previous defeats.

- Austrian Resurgence: Austria, under Archduke Charles, launched a surprise attack in April 1809, hoping to capitalize on French forces being tied down in Spain.

- Battles of Aspern-Essling (May 1809): Napoleon suffered his first significant personal battlefield defeat in nearly a decade, as the Austrians managed to repulse his attempts to cross the Danube, inflicting heavy casualties and forcing a French retreat. This showed Napoleon was not invincible.

- Battle of Wagram (July 1809): Despite the setback at Aspern-Essling, Napoleon regrouped and, a few weeks later, achieved a hard-fought but decisive victory over the Austrians at Wagram. This massive engagement involved hundreds of thousands of men and vast artillery barrages.

- Treaty of Schönbrunn (October 1809): This treaty further punished Austria, forcing it to cede more territory (including Western Galicia to the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, which worried Russia), pay a large indemnity, and align with France.

Dynastic Consolidation (1809-1811)

With his military power seemingly unchallenged on the continent after Wagram, Napoleon focused on securing his dynasty.

- Divorce of Joséphine (December 1809): Despite his deep personal affection, Napoleon divorced Empress Joséphine as she was unable to produce an heir, which he considered essential for the long-term stability and legitimacy of his empire.

- Marriage to Marie Louise of Austria (April 1810): He subsequently married Marie Louise, Archduchess of Austria, daughter of Emperor Francis I. This marriage forged a powerful (though ultimately fragile) dynastic alliance with one of Europe’s oldest royal houses.

- Birth of Napoleon II (March 1811): The marriage produced the desired male heir, Napoleon François Joseph Charles Bonaparte, who was immediately styled the “King of Rome,” signaling Napoleon’s aspirations for a lasting imperial dynasty.

Imperial Expansion and Consolidation (1808-1812)

By 1810, Napoleon’s empire reached its greatest territorial extent, controlling virtually all of continental Europe, either directly or through a network of client states:

- Direct Annexation: Belgium, parts of the Netherlands, the Rhineland, and significant portions of Italy were directly incorporated into the French Empire.

- Client Kingdoms: Napoleon placed his relatives on the thrones of various newly created or reorganized states:

- Kingdom of Italy: Napoleon himself was crowned King of Italy in 1805.

- Kingdom of Naples: Ruled by his brother Joseph, then his brother-in-law Joachim Murat.

- Kingdom of Holland: Ruled by his brother Louis until 1810, when it was annexed.

- Kingdom of Westphalia: Ruled by his brother Jérôme.

- Confederation of the Rhine: A league of German states allied with and dominated by France, established after the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806.

- Grand Duchy of Warsaw: Created from Polish territories seized from Prussia, a French client state that appealed to Polish national aspirations.

Continental System and Mounting Tensions with Russia (1810-1812)

The Continental System, Napoleon’s economic blockade against Great Britain, became the primary source of escalating tensions with Russia, setting the stage for the 1812 invasion.

- Russia’s Withdrawal: Tsar Alexander I found the Continental System severely damaging to Russia’s economy, which relied heavily on trade with Britain. By late 1810, Russia began to openly trade with Britain, effectively withdrawing from the blockade.

- Territorial Disputes: Russia was also increasingly alarmed by Napoleon’s expansionist policies, particularly his annexation of territories like Oldenburg (whose duke was Tsar Alexander’s brother-in-law) and his manipulation of Polish territories (the Grand Duchy of Warsaw), which Russia viewed as a potential springboard for a French invasion.

- Diplomatic Breakdown: Repeated diplomatic efforts failed to resolve these issues. Both sides began massive military preparations, knowing that war was increasingly inevitable.

The Invasion of Russia (June – December 1812)

Convinced that he needed to compel Tsar Alexander I back into the Continental System and secure his hegemony, Napoleon launched his ill-fated invasion of Russia.

- The Grande Armée: Napoleon assembled the largest army Europe had ever seen, the “Grande Armée,” numbering over 600,000 men. This multinational force included French, Polish, German, Italian, and other contingents.

- Initial Advance (June-August 1812): On June 24, 1812, the Grande Armée began crossing the Niemen River into Russian territory. Napoleon aimed for a swift, decisive battle to force the Russians to terms. However, the Russian commanders, particularly Barclay de Tolly, adopted a strategy of prolonged withdrawal and scorched earth, denying the French supplies and avoiding a pitched battle. This frustrated Napoleon’s strategy.

- Battle of Smolensk (August 1812): The first major engagement. Napoleon captured Smolensk, but at a high cost, and the Russian armies managed to avoid decisive destruction, retreating further east.

- Battle of Borodino (September 7, 1812): Approximately 70 miles west of Moscow, the Russians, now under the veteran General Mikhail Kutuzov, finally made a stand at Borodino. This was the largest and bloodiest single-day battle of the Napoleonic Wars. Both sides suffered horrific casualties (over 70,000 combined). While a tactical victory for Napoleon, it was a pyrrhic one, as the Russian army, though battered, was not destroyed.

- Occupation of Moscow (September 1812): Napoleon entered Moscow on September 14, finding the city largely abandoned. Soon after, massive fires (likely set by the retreating Russians) engulfed and destroyed much of the city, denying the French shelter and supplies.

- The Disastrous Retreat (October-December 1812): After waiting for over a month in Moscow for Tsar Alexander to negotiate (which he refused to do), Napoleon was forced to order a retreat as winter approached. The retreat became one of the greatest military disasters in history. The Grande Armée was decimated by:

- Scorched Earth: Lack of supplies and fodder.

- Harsh Winter: Bitter cold, snow, and ice (though initial losses were due to disease, starvation, and heat exhaustion).

- Russian Attacks: Relentless harassment by Cossacks, regular Russian forces, and partisan groups.

- Crossing the Berezina River (November 1812): A final, harrowing ordeal where thousands perished trying to cross the partially frozen river under Russian attack.

By December 1812, only a battered remnant (estimates vary, but perhaps 30,000-100,000 out of over 600,000) of the Grande Armée limped out of Russia. This catastrophic failure severely weakened Napoleon’s military power, shattered his aura of invincibility, and directly led to the formation of the Sixth Coalition against him, initiating his final decline.

Napoleon: Decline, Abdication, and Exile (1812-1821)

Napoleon’s Return from Elba, by Charles de Steuben, 1818

(Wiki Image By Charles de Steuben – http://www.firstempire.0catch.com/Campaigns/Hundred_Days/Phase_I/Rally_at_Grenoble/rally_at_grenoble.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50862200)

Napoleon’s decline began dramatically in 1812 and ended with his death in 1821, a period marked by catastrophic military defeats, the unraveling of his vast empire, and two exiles.

The Turning Point: Invasion of Russia (1812) 🇷🇺

The catastrophic invasion of Russia in 1812 marked the beginning of Napoleon’s downfall. Driven by Tsar Alexander I’s withdrawal from the Continental System and geopolitical ambitions, Napoleon assembled the “Grande Armée,” a massive force of over 600,000 men (the largest European army ever assembled at that time), including contingents from across his allied states.

- Campaign: Napoleon aimed for a swift, decisive victory. He pushed deep into Russia, eventually taking Moscow after the bloody Battle of Borodino (September 1812). However, the Russians adopted a scorched-earth policy, denying his army supplies.

- Disastrous Retreat: After a month in Moscow, with no surrender from the Tsar, Napoleon was forced to order a retreat in October as winter approached. The brutal Russian winter, relentless guerrilla attacks, starvation, disease, and the crossing of the Berezina River decimated his forces. Only a fraction of the Grande Armée (estimates range from 30,000 to 100,000) survived the ordeal, a catastrophic loss of manpower and prestige.

The Fall of the Empire (1813-1814)

The Russian disaster emboldened Europe. A new Sixth Coalition formed against France, comprising Russia, Prussia, Austria, Great Britain, and Sweden.

- War in Germany (1813): Despite quickly raising a new army, Napoleon faced overwhelming numbers. He suffered a decisive defeat at the Battle of Leipzig (October 1813), often called the “Battle of the Nations,” the largest battle in European history before World War I. This forced his retreat from Germany, and the Confederation of the Rhine dissolved.

- Defense of France (1814): Allied armies invaded France. Napoleon fought a brilliant defensive campaign, winning several tactical victories against numerically superior forces. However, his empire’s resources were exhausted, and his marshals, weary of war, began to refuse his commands.

- First Abdication (April 1814): With Allied forces occupying Paris, Napoleon’s marshals pressured him to abdicate unconditionally on April 6, 1814. He initially tried to abdicate in favor of his son, but the Allies rejected this.

- Exile to Elba: The victorious powers exiled Napoleon to Elba, a small island in the Mediterranean off the coast of Italy. He was allowed to retain his imperial title and a small personal guard. The Bourbon monarchy was restored in France under King Louis XVIII.

In his farewell address to the soldiers of the Old Guard on 20 April 1814, Napoleon said:

“Soldiers of my Old Guard, I have come to bid you farewell. For twenty years, you have accompanied me faithfully on the paths of honor and glory. …With men like you, our cause was [not] lost, but the war would have dragged on interminably, and it would have been a civil war. … So I am sacrificing our interests to those of our country. …Do not lament my fate; if I have agreed to live on, it is to serve our glory. I wish to write the history of the great deeds we have done together. Farewell, my children!”

The Hundred Days and Final Defeat (1815) 🇫🇷

Less than a year into his exile, Napoleon made a daring return.

- Escape from Elba (February 1815): Sensing discontent with the restored Bourbon monarchy and a chance to regain power, Napoleon escaped from Elba. He landed in France on March 1, 1815.

- March to Paris: His journey north became a triumphal march. Soldiers sent to arrest him instead rallied to his side, and King Louis XVIII fled. Napoleon entered Paris on March 20, 1815, without firing a shot, beginning the period known as the “Hundred Days.”

- Battle of Waterloo (June 18, 1815): European powers immediately declared him an outlaw and mobilized new armies. Napoleon launched a pre-emptive strike into Belgium, seeking to defeat the British and Prussian armies before they could combine. His final, decisive defeat came at the Battle of Waterloo on June 18, 1815, where his forces were crushed by a combined Anglo-Allied army under the Duke of Wellington and a Prussian army under Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher.

Second Abdication and Exile to Saint Helena (1815-1821)

- Second Abdication (June 1815): After Waterloo, Napoleon returned to Paris, but with no political support left, he abdicated for a second and final time on June 22, 1815.

- Exile to Saint Helena: Fearing another escape, the British and their allies decided on a more remote prison. Napoleon was exiled to the isolated British island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic, over 1,800 miles from the nearest mainland. He arrived in October 1815 and spent the remainder of his life there under strict guard.

- Death (May 5, 1821): Napoleon died on Saint Helena on May 5, 1821, at the age of 51. The official cause of death was stomach cancer, though speculation about arsenic poisoning persisted for many years. He was initially buried on the island, but his remains were later returned to France in 1840 and interred in Les Invalides in Paris.

This period saw the spectacular collapse of Napoleon’s empire, brought about by his military overreach, the determined resistance of a united Europe, and ultimately, his final, decisive defeat.

Napoleon: Advisors

Louis-Alexandre Berthier

Prince of Neuchâtel and Valangin, Prince of Wagram

(Wiki Image By Jacques Augustin Catherine Pajou – Joconde database: entry 000PE004802 / Jimmy44, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=74545926)

Napoleon Bonaparte, despite his highly centralized and often autocratic style of leadership, relied heavily on a relatively small but immensely capable inner circle of advisors. These individuals, whether military, political, or administrative, were crucial to the functioning and expansion of his vast empire.

Here are the key types of advisors and specific individuals Napoleon relied upon:

- The Marshals of the Empire (Military Advisors)

Napoleon’s most visible and critical advisors were his Marshals. He created this prestigious title in 1804, eventually appointing 26 men. They were his top military commanders, leaders of his Corps, and executors of his grand strategies. Many of them rose from humble origins based purely on merit, fostering intense loyalty.

- Louis-Alexandre Berthier: Napoleon’s indispensable Chief of Staff. Berthier was a brilliant organizer, administrator, and logistician, known for his ability to translate Napoleon’s often rapid and complex orders into clear, detailed instructions for the entire army. He was the “brain” behind the Grande Armée’s efficient movements and supply, often called Napoleon’s “wife” due to his constant presence and indispensable role.

- Louis-Nicolas Davout: Often considered Napoleon’s most capable and reliable marshal. Known as the “Iron Marshal” for his strict discipline and tactical prowess, he achieved independent victories (e.g., Auerstedt in 1806) and was central to many of Napoleon’s greatest successes.

- Jean Lannes: A close personal friend and one of Napoleon’s most courageous and beloved marshals. Known for his audacious battlefield leadership, he was tragically killed at the Battle of Aspern-Essling in 1809, a significant personal loss for Napoleon.

- André Masséna: Called “Dear Child of Victory” by Napoleon, Masséna was a brilliant tactical commander, known for his resilience and ability to fight effectively even when outnumbered or in difficult situations.

- Michel Ney: The “Bravest of the Brave,” renowned for his personal courage and leadership in combat, often leading charges and rearguards, though sometimes tactically impetuous.

- Joachim Murat: Napoleon’s brother-in-law and his flamboyant, daring cavalry commander. Murat was unparalleled in leading mass cavalry charges and reconnaissance missions.

- Jean-de-Dieu Soult: A versatile and capable commander, skilled in both offensive and defensive operations, who held significant commands throughout the Napoleonic Wars.

- Political and Administrative Advisors

Beyond the military, Napoleon relied on a select group of astute politicians and administrators who helped him govern France and manage his empire.

- Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord: A cunning and pragmatic Foreign Minister. Talleyrand was a master diplomat who served Napoleon for much of his ascent, expertly negotiating treaties and managing international relations. However, he was also famously self-serving and eventually worked against Napoleon when he perceived his downfall as inevitable, advising the Allies during the Bourbon Restoration.

- Joseph Fouché: The highly effective and often ruthless Minister of Police. Fouché maintained internal security, suppressed dissent, ran an extensive spy network, and was crucial for controlling France and its occupied territories. His ruthlessness and ambition meant Napoleon often distrusted him, but he recognized Fouché’s indispensability.

- Jean-Jacques-Régis de Cambacérès: Second Consul under the Consulate and later Arch-Chancellor of the Empire. A skilled jurist, Cambacérès was instrumental in the drafting and codification of the Napoleonic Code, serving as a key legal advisor and helping to ensure administrative continuity.

- Gaëtan Gourgaud & Henri Gratien Bertrand (during exile): While not “advisors” in the traditional governing sense, these were loyal generals who accompanied Napoleon to Saint Helena and served as his companions and scribes, helping him dictate his memoirs and reflections on his campaigns and policies, effectively shaping his historical narrative.

- Family Members (as Political Tools/Advisors)

Napoleon also used his family to extend his political control, placing his brothers on thrones across Europe, though they often proved to be more of a challenge than reliable advisors.

- Joseph Bonaparte: Napoleon’s elder brother, whom he made King of Naples and then King of Spain. While intended to be loyal administrators, Joseph often struggled with the complexities of governing and chafed under Napoleon’s constant interference.

- Louis Bonaparte: Another brother, appointed King of Holland. Louis often prioritized Holland’s interests over Napoleon’s Continental System, leading to friction and eventually the annexation of Holland into France.

Napoleon’s style was to be the ultimate decision-maker. Still, the loyalty and competence of this diverse group of advisors were fundamental to his ability to rise to and maintain his immense power.

Here are images of some of Napoleon’s key advisors and an illustration of him with his counsel:

- Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord: A portrait of Talleyrand, who served as Napoleon’s chief diplomat and foreign minister.

- Joseph Fouché: A portrait of Fouché, the powerful and feared Minister of Police under Napoleon.

- Napoleon with his advisors: An illustration depicting Napoleon in a setting with his advisors and other prominent figures of his court.

Napoleon: Civilization

The Coronation of Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David (1804)

(Wiki Image By Jacques-Louis David / Georges Rouget – art database, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=546742)

Napoleon: Economic

Napoleon Bonaparte’s economic policies were deeply intertwined with his overarching goals of stabilizing France, funding his vast military campaigns, and establishing French economic hegemony over Europe to defeat Great Britain. While he brought much-needed order after the chaos of the Revolution, his economic measures often had mixed results, particularly for the wider European continent.

Key Economic Policies and Reforms:

- Creation of the Bank of France (1800):

- Purpose: One of Napoleon’s most crucial financial reforms was the establishment of the Banque de France (Bank of France). Its primary goals were to stabilize the French economy, restore confidence in the financial system after the turmoil of the Revolution, and provide a reliable source of credit.

- Role: The bank was granted the exclusive privilege of issuing a unified national currency (the franc germinal, based on both gold and silver), managing government finances, and providing loans to both the government (crucial for war funding) and private enterprises. This centralized financial institution laid the groundwork for modern central banking in France and served as a model for other European nations.

- Taxation System:

- Napoleon implemented a more centralized, efficient, and equitable tax system compared to the chaotic and corrupt methods of the Ancien Régime and the Revolution.

- He introduced direct taxes (on land, property, and personal income) and indirect taxes (on goods like salt, tobacco, and alcohol), which were more consistently collected.

- This improved tax collection significantly increased state revenue, vital for funding his military. However, the heavy taxation often proved unpopular, especially in conquered territories.

- The Continental System (1806-1814):

- Purpose: This was Napoleon’s most ambitious and economically disruptive policy, designed to cripple Great Britain, his archenemy, by economic warfare. The system prohibited all trade between continental Europe (under French control or influence) and Great Britain.

- Impact on Britain: While it did cause some economic hardship and unemployment in Britain, forcing it to seek new markets, Britain’s strong navy allowed it to maintain global trade routes (e.g., with its colonies and new markets in South America). Smuggling became rampant, undermining the blockade.

- Impact on France and Europe: The Continental System often hurt France and its allies more than it did Britain.

- Shortages: Europe faced shortages of colonial goods (sugar, coffee, cotton) and cheaper British-manufactured goods.

- Economic Decline in Ports: Port cities (like Marseille and Bordeaux) that relied on maritime trade suffered greatly.

- Uneven Industrialization: While some French industries (especially textiles in the north and east) initially benefited from reduced British competition, France could not fully supply the entire European market. This led to gluts in some areas and shortages in others, causing price volatility and economic instability.

- Resentment: The system was widely resented across Europe, seen as a tool of French economic exploitation rather than a benefit. This resentment contributed to growing anti-French sentiment and resistance movements.

- Overall Failure: The Continental System was ultimately a major miscalculation, contributing significantly to Napoleon’s overreach and leading to costly military ventures (like the Peninsular War and the invasion of Russia) aimed at enforcing the blockade.

- Agricultural Policies:

- Napoleon recognized the importance of a strong agricultural base. He introduced protective tariffs for agricultural products and encouraged peasants to cultivate more land.

- His legal reforms in the Napoleonic Code formally recognized peasant land ownership, which provided stability and incentive for agricultural production.

- Infrastructure Development:

- Napoleon invested in extensive infrastructure projects within France and its controlled territories, including the construction of roads, bridges, and canals. These improvements aimed to facilitate the movement of goods, people, and, crucially, military forces, thereby boosting internal trade and administration.

Overall Economic Impact:

Napoleon’s economic policies had a dual nature:

- Positive (for France, initially): He brought financial stability and order to post-revolutionary France, creating modern institutions like the Bank of France and streamlining taxation. This fostered a period of relative prosperity and confidence within France itself.

- Negative (for Europe and in the long run): The constant warfare, heavy taxation, and especially the disruptive Continental System caused widespread economic hardship, trade disruption, and shortages across much of Europe. The immense human and financial cost of his wars drained resources and stifled long-term economic development in many regions, ultimately contributing to the collapse of his empire.

Here are images illustrating various economic aspects of Napoleon’s reign:

- The Continental System: This image represents Napoleon’s Continental System, a large-scale embargo against British trade. This policy had significant economic consequences across Europe, both for those who complied and those who resisted.

- Founding of the Bank of France: This image depicts the establishment of the Bank of France in 1800. This was a key financial reform by Napoleon to stabilize the French economy and manage the national debt.

- The Napoleonic Code (Code Civil): This image relates to the Napoleonic Code, which standardized French law. Its provisions on property ownership and contracts had a profound and lasting impact on the economic and legal systems of France and other European nations.

- Napoleon’s Public Works: This image illustrates one of the many infrastructure projects initiated by Napoleon’s government. These public works, such as canals, roads, and monuments, were intended to stimulate the economy, provide employment, and enhance the grandeur of the empire.

Napoleon: Farming

What was the state of farming in France during Napoleon’s reign, and how did his policies affect agricultural practices? How did Napoleon seek to improve or utilize the agricultural sector of his empire? Napoleon Bonaparte’s approach to farming and agriculture was pragmatic and focused on stabilizing the rural economy, ensuring food security for France and his armies, and solidifying the loyalty of the peasantry. His policies built upon the revolutionary changes that had already begun to dismantle the old feudal system.

The State of French Agriculture at the Outset

Before Napoleon came to power, French agriculture was emerging from centuries of feudal practices and the upheaval of the Revolution:

- Abolition of Feudalism: The French Revolution had already abolished feudal dues and privileges, freeing peasants from many traditional burdens and allowing them to become landowners. This was a monumental change.

- Land Redistribution: The sale of confiscated Church property and the lands of émigré nobles during the Revolution had led to a significant redistribution of land, often benefiting peasants who could afford to buy plots. This created a large class of smallholding farmers.

- Subsistence Farming: Most farming was still subsistence-oriented, with traditional methods and relatively low yields.

Napoleon’s Agricultural Policies and Impact

Napoleon understood that a contented and productive peasantry was vital for both political stability and military strength.

- Confirmation of Land Ownership:

- The Napoleonic Code (Code Civil des Français), enacted in 1804, formally recognized and protected private property rights. This was immensely important for the millions of peasants who had acquired land during the Revolution, as it secured their ownership and provided a legal basis for their holdings. This ensured their loyalty to his regime.

- He also introduced a special land registry which, by 1814, had registered millions of plots, further cementing land ownership.

- Food Security and Price Stability:

- Ensuring access to cheap and abundant food, particularly bread, was a priority for urban populations and the military. Napoleon’s government ensured that wages kept pace with prices and implemented state price regulation for essential goods, such as bread and meat, particularly in Paris.

- This direct intervention in the market aimed to prevent the food shortages and soaring prices that had fueled revolutionary unrest.

- Encouraging Production and Innovation:

- Napoleon, advised by agronomists, promoted efforts to improve agricultural productivity.

- He encouraged the cultivation of new crops like the potato and sugar beet. The latter became particularly important under the Continental System, as France sought to replace imported colonial sugar with its own. This spurred innovation in beet processing, leading to significant economic benefits in regions where it was grown.

- He supported the biological regeneration of French herds and agriculture through state initiatives. For instance, he reestablished national stud farms (by decree of July 4, 1806) to improve horse breeds, essential for the cavalry and transport.

- He also promoted the breeding and acclimatization of Merino sheep (brought from Spain) to improve wool quality for textile manufacturing, reducing dependence on imports for military uniforms.

- He encouraged the establishment of nurseries in departments to multiply various fruit species and acclimatize new plant species.

- Impact of the Continental System:

- The Continental System (1806-1814), while aimed at Britain, had a mixed and often challenging impact on continental agriculture. It cut off imports of colonial goods like cane sugar, cotton, and indigo, which forced substitute industries to develop on the continent (e.g., sugar beet, madder for dye).

- While some agricultural sectors benefited from reduced British competition and new domestic demand, others suffered from trade disruption and the inability to export surplus produce.

- Infrastructure and Trade Facilitation:

- Napoleon invested in improving roads and canals. While primarily for military movement, these also facilitated the transport of agricultural goods to markets, benefiting farmers and urban consumers.

- His efforts in standardizing laws and removing internal barriers (like tolls) also made it easier and cheaper to transport agricultural products over longer distances.

In essence, Napoleon’s approach to farming was pragmatic and state-driven. He ensured the gains of the Revolution for the peasants, secured food supplies, and strategically promoted agricultural sectors that could support his empire’s needs, especially under the pressures of war and blockade.

Here are images illustrating farming and rural life during the Napoleonic era:

- Napoleonic Era Agriculture (Peasant Farmer): This image depicts a peasant farmer engaged in agricultural work, representative of the majority of the French population during this period.

- French Farming Methods (Early 19th Century): This image shows farming methods and tools used in France during the early 1800s, reflecting the technology and practices of the time. http://googleusercontent.com/image_collection/image_retrieval/1847584039573512574

- Rural Life in France (Napoleonic Wars): This image illustrates rural life and its connection to the Napoleonic Wars, showing the impact of the military campaigns on the countryside.

- French Village Harvest (Early 1800s): This image depicts a harvest scene in a French village, highlighting the communal and seasonal nature of agricultural labor.

Napoleon: Geopolitics

What were the key geopolitical objectives and strategies of Napoleon Bonaparte? How did his actions reshape the political map of Europe? Napoleon Bonaparte’s geopolitical strategy was defined by a relentless drive to establish French hegemony over continental Europe and to challenge Great Britain’s global dominance. His vision profoundly reshaped the political map and international relations of the early 19th century.

- French Hegemony over Continental Europe

Napoleon’s primary geopolitical objective was to make France the undisputed master of Europe.

- Military Conquest and Annexation: Through a series of brilliant military campaigns and decisive victories (e.g., Austerlitz, Jena-Auerstedt, Wagram), Napoleon conquered or subjugated large parts of Europe. Key territories like Belgium, parts of the Netherlands, the Rhineland, and significant portions of Italy were directly annexed into the French Empire.

- Client States and Satellite Kingdoms: Beyond direct annexation, Napoleon created a vast network of client states and satellite kingdoms. He placed his relatives (brothers Joseph, Louis, Jérôme, and his stepson Eugène) on the thrones of these newly created or reorganized entities, such as the Kingdom of Italy, the Kingdom of Naples, the Kingdom of Holland, and the Kingdom of Westphalia. This allowed him to exert control over vast territories without direct occupation.

- Dissolution of Old Orders: One of his most significant geopolitical acts was the dissolution of the ancient Holy Roman Empire in 1806, which had existed for over a thousand years. In its place, he created the Confederation of the Rhine, a league of German states allied with and dominated by France. This dramatically simplified the political map of Germany and inadvertently laid the groundwork for future German unification.

- Redrawing European Borders: Napoleon constantly redrew the map of Europe. He consolidated numerous small Italian states into larger entities, similarly simplified the German political landscape, and carved out new territories (e.g., the Grand Duchy of Warsaw from Prussian lands).

- The Continental System (Economic Warfare against Britain)

Lacking the naval power to directly invade or defeat Great Britain, Napoleon resorted to economic warfare.

- Purpose: The Continental System, implemented through decrees like the Berlin Decree (1806) and Milan Decree (1807), aimed to cripple the British economy by prohibiting all trade between continental Europe and Great Britain. Napoleon believed that starving Britain of markets and resources would lead to economic collapse and force it to make peace on French terms.

- Effects and Failure: The system was difficult to enforce, leading to widespread smuggling and harming the economies of France’s own allies and subjects more than it did Britain. Britain maintained global trade routes and found new markets outside Europe (e.g., South America). The system’s enforcement led to costly military ventures (e.g., Peninsular War, invasion of Russia) and ultimately contributed significantly to Napoleon’s downfall.

- Challenges to the Balance of Power and International Relations

- Coalition Wars: Napoleon’s expansionist policies and disregard for the traditional balance of power constantly provoked coalitions of other European powers (Britain, Austria, Prussia, Russia) who sought to contain French dominance. These “Coalition Wars” defined much of his reign.

- Rise of Nationalism: Paradoxically, Napoleon’s conquests, while imposing French models of administration and law, inadvertently fueled powerful nationalist sentiments in occupied territories (e.g., Spain, Germany, Italy). Resistance movements, like the Peninsular War, demonstrated the power of popular resentment against foreign occupation, a new and potent force in European geopolitics.

- Global Impact: The Napoleonic Wars, though centered in Europe, had global repercussions.

- Louisiana Purchase (1803): Napoleon’s financial needs led him to sell the vast Louisiana Territory to the United States, doubling the size of the young American nation and shaping its future geopolitical trajectory.

- Latin American Independence: Spain’s weakening control over its American colonies during the Napoleonic Wars (due to Napoleon’s invasion of Spain) provided a crucial window for independence movements across Latin America to flourish.

- British Imperial Expansion: British naval supremacy, solidified during the wars, laid the groundwork for Britain’s vast global empire in the 19th century.

- Legacy

Napoleon’s geopolitical strategies, though ultimately unsustainable, irrevocably altered Europe. The old feudal order was severely weakened, and the seeds of modern nation-states, particularly in Germany and Italy, were sown. The Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) attempted to restore a balance of power and a conservative order after Napoleon’s fall. Still, it could not fully undo the profound changes in national consciousness and political structures that he had instigated across the continent.

Here are images illustrating key geopolitical events and concepts from the Napoleonic era:

- Map of Napoleonic Europe (1812): This image shows the maximum extent of the French Empire and its dependencies in Europe at the height of Napoleon’s power, before he invaded Russia.

- Map of the Continental System: This map illustrates Napoleon’s economic blockade against Great Britain, showing the territories that were part of the system and those that were not, which had significant geopolitical implications.

- Illustration of the Treaty of Tilsit (1807): This image depicts the meeting between Napoleon Bonaparte and Tsar Alexander I on a raft in the middle of the Neman River, which resulted in a treaty that reshaped the map of Central Europe and created a temporary Franco-Russian alliance.

- Illustration of the Congress of Vienna (1815): This image shows the diplomatic conference that convened after Napoleon’s final defeat to redraw the political map of Europe and restore the balance of power.

- Map of the Battle of Austerlitz (1805): This map illustrates the military maneuvers and positions during one of Napoleon’s most significant victories, which had major geopolitical consequences, including the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire and the creation of the Confederation of the Rhine.

Napoleon: Law

Napoleon Bonaparte’s most profound and enduring legacy is arguably his comprehensive reform of the French legal system, culminating in the Napoleonic Code. This legal framework profoundly impacted not only France but also civil law jurisdictions worldwide.

The Need for Reform

Before Napoleon, France’s legal system was a chaotic patchwork of diverse laws:

- Regional Variation: Laws varied greatly from one region to another. Roman law often prevailed in the south, while customary (feudal and Germanic) law dominated in the north.

- Complexity and Injustice: There were numerous exemptions, privileges, and special charters, leading to a complex, often ambiguous, and inconsistent system that perpetuated inequalities.

- Revolutionary Demand: The French Revolution had abolished many feudal privileges and demanded a unified legal code, but previous attempts to draft one had largely failed.

The Napoleonic Code (Code Civil des Français – 1804)

Recognizing the need for a clear, uniform legal system to consolidate the achievements of the Revolution and stabilize his regime, Napoleon initiated the drafting of the Civil Code in 1800. A commission of four eminent jurists led the process, with Napoleon himself actively participating in many of the Council of State’s drafting sessions. The Code was officially published on March 21, 1804.

Key Principles and Features:

- Equality Before the Law: It established the fundamental principle that all male citizens were equal before the law, abolishing the privileges based on birth, class, or hereditary nobility. This was a direct legacy of the Revolution.

- Protection of Private Property: The Code strongly emphasized and secured the right to private property, which appealed to the burgeoning middle class and the millions of peasants who had acquired land during the Revolution.

- Religious Freedom: It affirmed the secular character of the state and guaranteed freedom of religion, consistent with the Concordat of 1801.

- Abolition of Feudalism: It definitively abolished all remaining vestiges of feudalism, including feudal dues and serfdom, across all territories where it was implemented.

- Standardized Family Law (with caveats):

- It made marriage a civil contract rather than purely a religious sacrament, and allowed for divorce.