John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and Cornelius Vanderbilt: The Gilded Age

The Gilded Age (roughly 1870-1900) was a period of rapid industrialization, economic growth, and immense wealth creation in the United States, but also of great social inequality and political corruption. John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and Cornelius Vanderbilt are the quintessential figures of this era, embodying its core characteristics as they built vast monopolies that reshaped American industry.

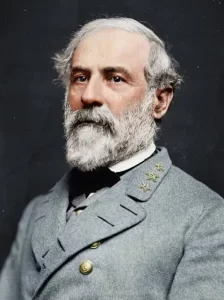

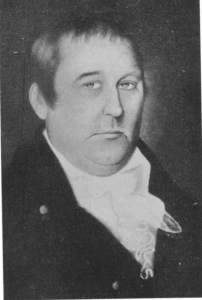

John D. Rockefeller (1839–1937): The Oil Tycoon

- Industry: Oil.

- Rise to Power: Rockefeller started in a modest business and, by 1870, founded Standard Oil. He pioneered the business practice of horizontal integration, ruthlessly buying up or driving out competitors in the refining industry. He then expanded with vertical integration, controlling every aspect of the oil business from drilling to distribution.

- Legacy: By the 1880s, Standard Oil controlled over 90% of the country’s oil production and transportation, making it one of the wealthiest companies in history. His methods were widely condemned as anti-competitive and led to the passage of antitrust laws, eventually resulting in the company’s breakup in 1911. Late in life, Rockefeller turned to massive philanthropy, endowing institutions like the University of Chicago and the Rockefeller Foundation, aiming to improve medicine and education.

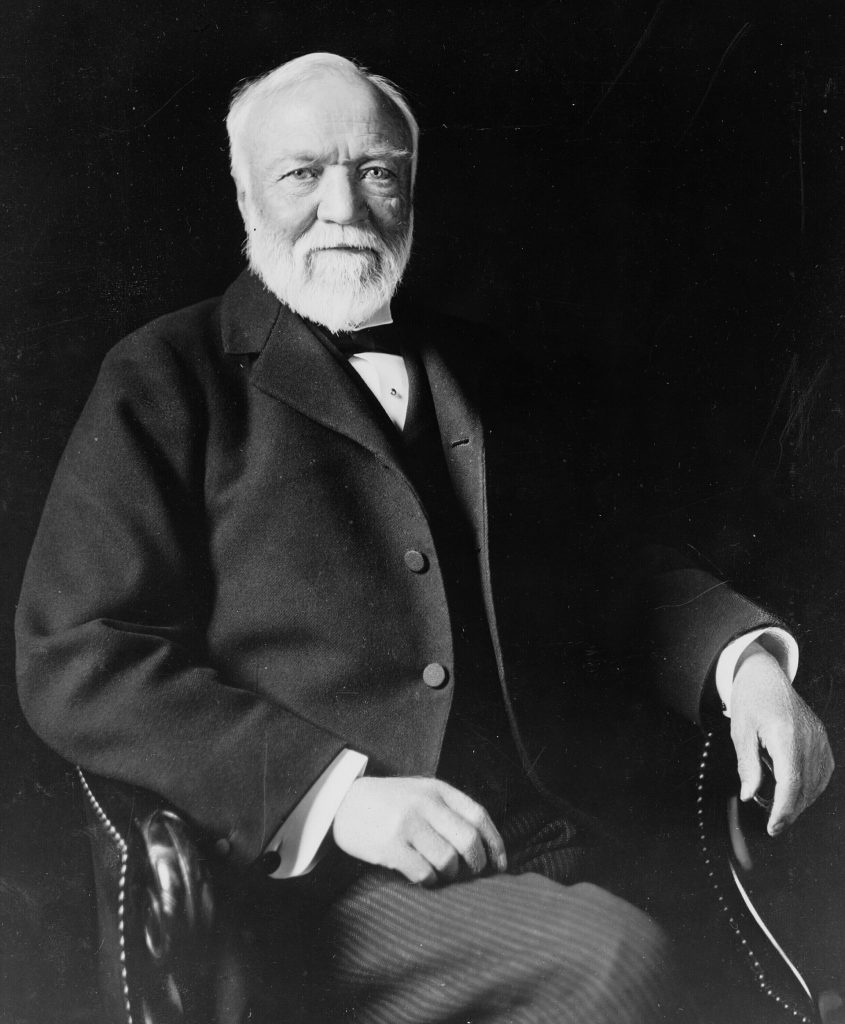

Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919): The Steel Magnate

- Industry: Steel.

- Rise to Power: A Scottish immigrant who started as a bobbin boy in a textile mill, Carnegie built his fortune through a combination of shrewd business deals and technological innovation. He adopted the Bessemer process for steel production, which was far more efficient and cheaper. He used vertical integration to control the entire steel-making process, from coal and iron ore fields to the final rail factory.

- Legacy: His company, Carnegie Steel, became the largest steel producer in the world. He sold it to J.P. Morgan in 1901 for a staggering sum, which formed the basis for U.S. Steel. After selling his company, Carnegie dedicated himself to philanthropy, building thousands of libraries, concert halls (Carnegie Hall), and universities, famously articulating his philosophy of giving in his essay, “The Gospel of Wealth,” which argued that the rich had a moral obligation to use their wealth to benefit society.

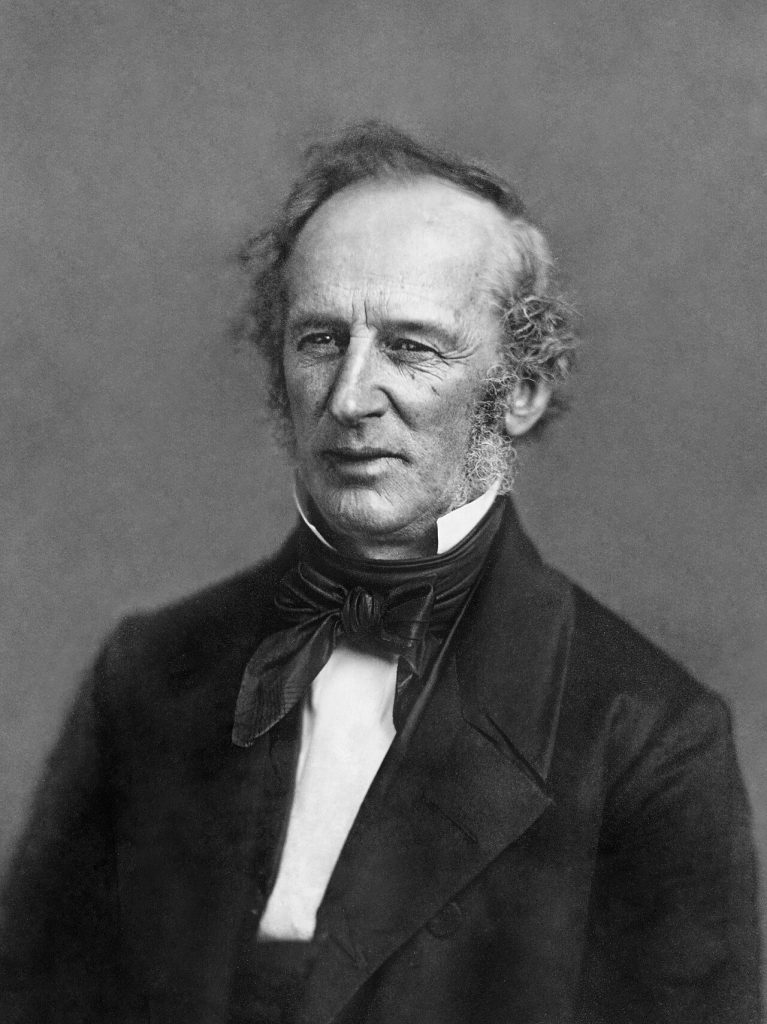

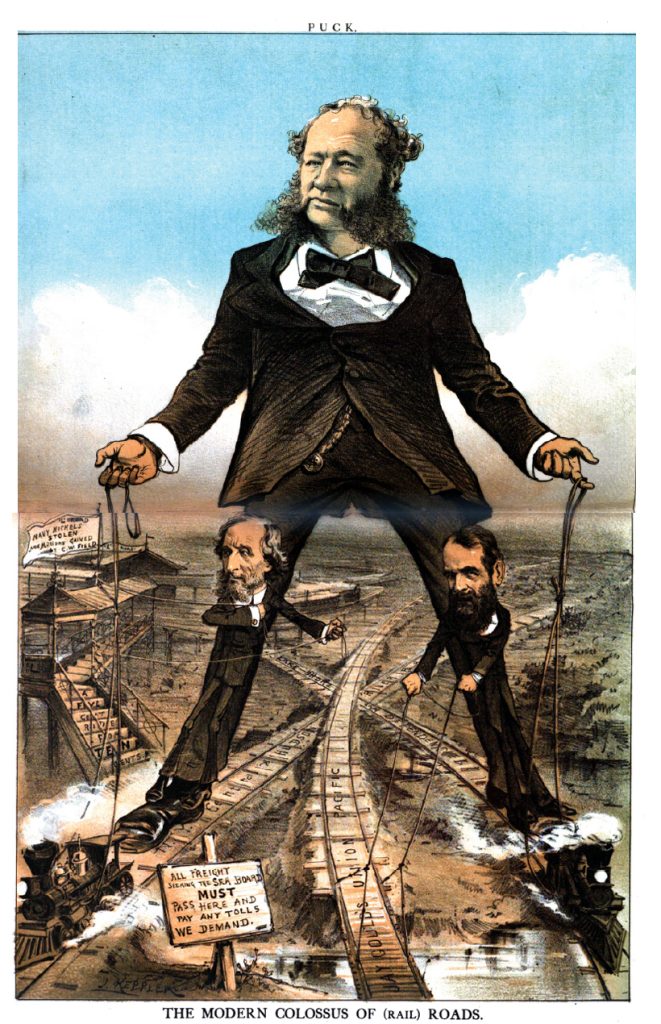

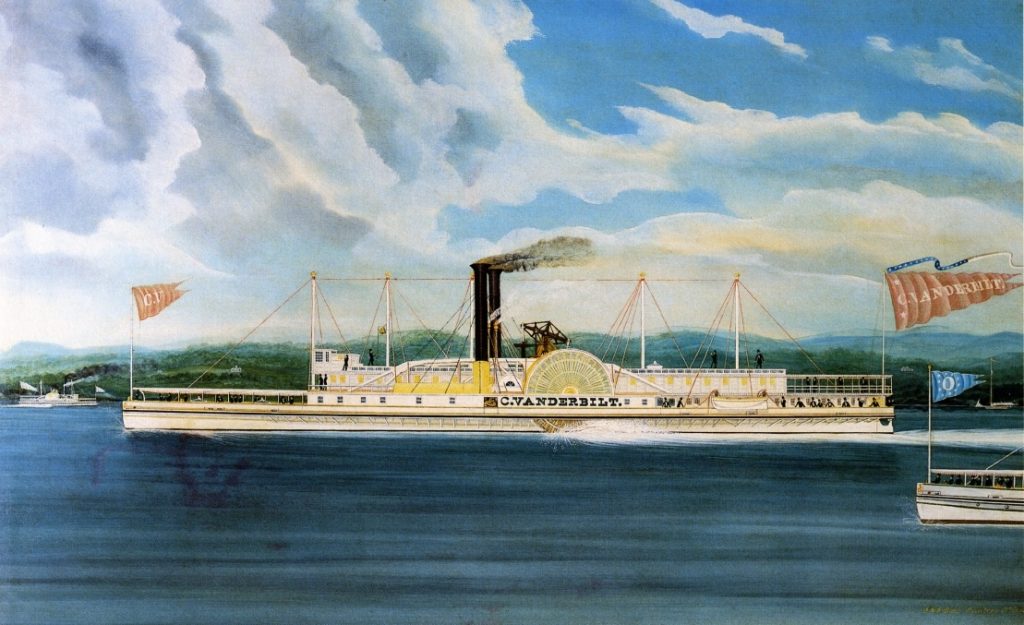

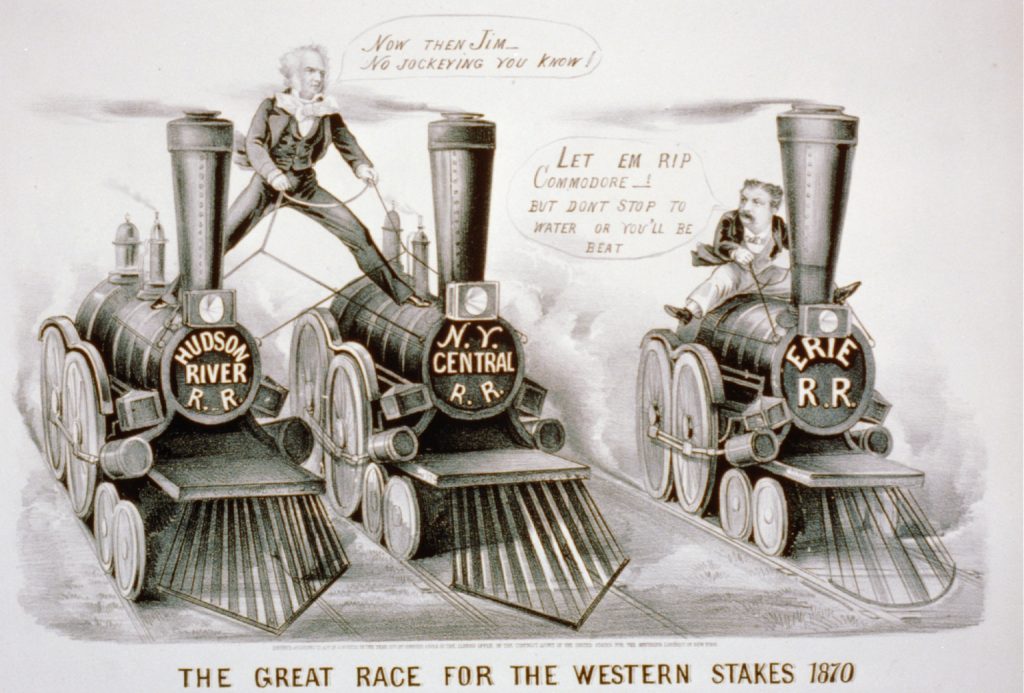

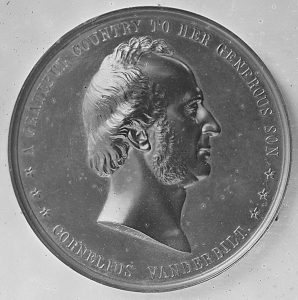

Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794–1877): The Railroad Baron

- Industry: Shipping and railroads.

- Rise to Power: Known as “The Commodore,” Vanderbilt began his career in ferries and steamships, where he was a cutthroat competitor who often engaged in price wars to drive rivals out of business. In his sixties, he shifted his focus entirely to railroads, recognizing their potential. He systematically acquired and consolidated numerous smaller, competing lines into a powerful and efficient network, most notably the New York Central Railroad.

- Legacy: He was a master of finance and organization who demonstrated the power of a vast, integrated rail system. By controlling key routes, he amassed an immense fortune and became one of the first great railroad barons. His ruthless business tactics earned him a “Robber Baron” reputation. Still, his actions also pioneered the creation of the massive corporate structures that would dominate the American economy for a century. He was a less systematic philanthropist than Rockefeller or Carnegie, but he did make a notable contribution by endowing Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee.

These three men personified the duality of the Gilded Age. They were seen as both “Robber Barons,” for their predatory business tactics, exploitation of workers, and monopolistic control, and as “Captains of Industry,” for their visionary leadership, technological innovation, and creation of the infrastructure that built modern America. Their lives laid the foundation for the corporate capitalism of the 20th century and, through their philanthropy, reshaped American culture, education, and medicine.

John D. Rockefeller (1839–1937): The Oil Tycoon

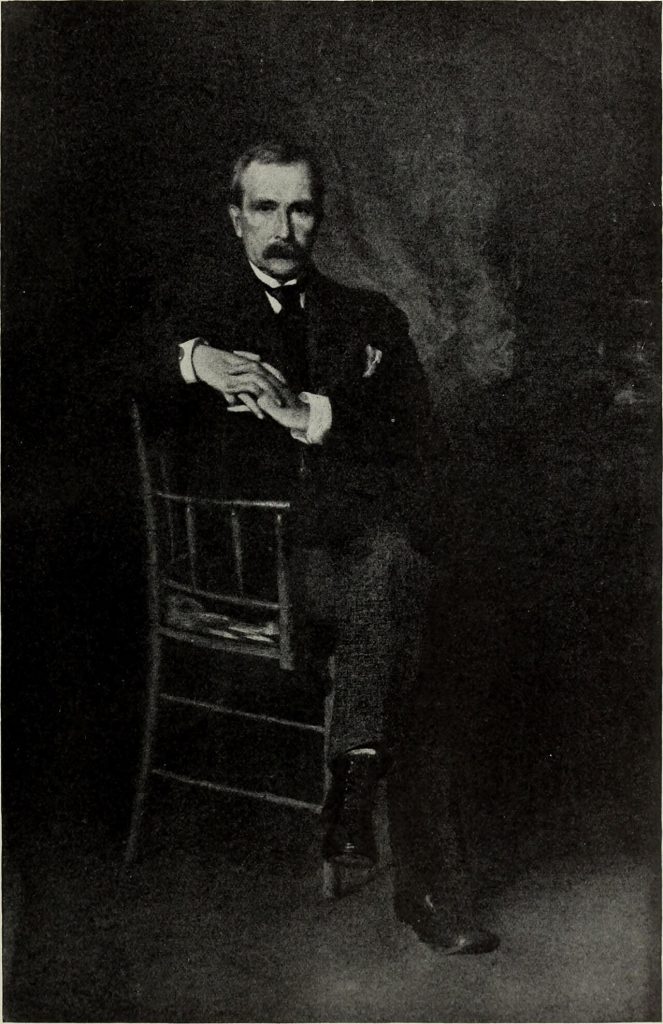

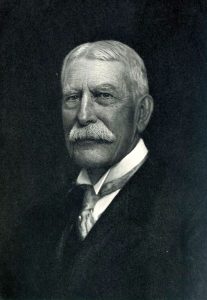

Portrait of John D Rockefeller by Eastman Johnson, 1895

(Wiki Image By Internet Archive Book Images – https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14582077667/Source book page: https://archive.org/stream/internationalstu10newy08/internationalstu10newy08#page/n186/mode/1up, No restrictions, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=43916235)

John D. Rockefeller Quotes

John D. Rockefeller was known for his sharp business mind, but also for his deep religious beliefs and a commitment to philanthropy later in life. His quotes reflect this combination of business savvy and personal philosophy. Here are some of his most famous and insightful quotes:

On Business and Success:

- “I would rather earn 1% off a 100 people’s efforts than 100% of my own efforts.”

- “Don’t be afraid to give up the good to go for the great.”

- “The ability to deal with people is as purchasable a commodity as sugar or coffee, and I will pay more for that ability than for any other under the sun.”

- “I always tried to turn every disaster into an opportunity.”

- “If you want to succeed you should strike out on new paths, rather than travel the worn paths of accepted success.”

- “The secret of success is to do the common things uncommonly well.”

- “A friendship founded on business is a good deal better than a business founded on friendship.”

- “Good management consists in showing average people how to do the work of superior people.”

On Wealth and Life:

- “The poorest man I know is the man who has nothing but money.”

- “The only question with wealth is, what do you do with it?”

- “I believe the power to make money is a gift of God . . . to be developed and used to the best of our ability for the good of mankind.”

- “I know of nothing more despicable and pathetic than a man who devotes all the hours of the waking day to the making of money for money’s sake.”

- “I believe that thrift is essential to well-ordered living and that economy is a prime requisite of a sound financial structure, whether in government, business or personal affairs.”

On Responsibility and Philanthropy:

- “Every right implies a responsibility; every opportunity, an obligation; every possession, a duty.”

- “Charity is injurious unless it helps the recipient to become independent of it.”

- “Next to doing the right thing, the most important thing is to let people know you are doing the right thing.”

- “The only thing which is of lasting benefit to a man is that which he does for himself. Money which comes to him without effort on his part is seldom a benefit and often a curse.”

A Chronology of John D. Rockefeller’s Life

John D. Rockefeller’s life spanned a period of immense change in the United States, from the pre-Civil War era to the Great Depression. His career can be broadly divided into three phases: his early life and rise to business, the building of the Standard Oil monopoly, and his later years as a philanthropist.

Early Life and Business Career

- 1839: John Davison Rockefeller is born in Richford, New York.

- 1853: His family moves to Cleveland, Ohio.

- 1855: At age 16, Rockefeller gets his first job as a bookkeeper. He begins meticulously tracking his finances, including his charitable donations.

- 1859: He and a partner establish a commission merchant business. This same year, the first oil well was drilled in Titusville, Pennsylvania, sparking the oil boom.

- 1863: Rockefeller enters the oil refining business, building his first refinery near Cleveland.

- 1870: He and his partners incorporate the Standard Oil Company of Ohio, with a capital of $1 million.

Standard Oil and the Gilded Age

- 1872: In a period known as the “Cleveland Massacre,” Rockefeller buys out 22 of his 26 competitors in Cleveland, a key step toward consolidating the oil industry.

- 1881: Standard Oil is reorganized into the Standard Oil Trust, the first large-scale business trust in the U.S. It controls about 90% of the nation’s oil refineries and pipelines, giving it a near-monopoly.

- 1890: Congress passes the Sherman Antitrust Act to combat monopolies and trusts like Standard Oil.

- 1897: Rockefeller officially retires from the day-to-day operations of Standard Oil to focus on philanthropy, though he retains a large ownership stake.

- 1902-1904: Muckraking journalist Ida Tarbell’s exposé, The History of the Standard Oil Company, is published, detailing Rockefeller’s ruthless business tactics and turning public opinion against the company.

Philanthropy and Legacy

- 1901: He establishes the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (later Rockefeller University).

- 1911: After years of litigation, the U.S. Supreme Court orders the dissolution of the Standard Oil Trust for violating antitrust laws. It is broken up into 34 separate companies, including what would become ExxonMobil and Chevron.

- 1913: The Rockefeller Foundation is established, with a focus on public health, education, and medical research.

- 1916: Rockefeller’s net worth soars following the breakup of Standard Oil, making him the nation’s first billionaire.

- 1937: John D. Rockefeller dies at the age of 97, having given away more than $500 million to various causes.

John D. Rockefeller YouTube Video

Rockefeller: The World’s First Billionaire

- Views: 7 Million

- Channel: MagnatesMedia

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fNh_GyRbJDA

- Description: This is one of the most-viewed recent documentaries on Rockefeller, offering a comprehensive look at how he built his empire and became the world’s first billionaire.

The history of the Rockefeller family – documentary

- Views: 401,000

- Channel: I’m a millionaire

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ptreqGLGabc

- Description: A feature-length documentary that explores the entire Rockefeller family history, starting with John D. Rockefeller’s rise to power.

Rockefeller – The Original Billionaire

- Views: 244,000

- Channel: The People Profiles

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iN8prtqM35s

- Description: This video provides a detailed biographical profile of Rockefeller, focusing on his life story and business strategies.

The Rockefeller Dynasty: Power, Scandals, and Secrets Behind America’s First Billionaire Family

- Views: 57,000

- Channel: The Empire Inside

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d-epfEhLomU

- Description: A documentary that delves into the more controversial aspects of the Rockefeller family’s history, including scandals and secrets.

American Titans Documentary – John D Rockefeller

- Views: 9,600

- Channel: Business Documentaries

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wNZP65qk6rc

- Description: Part of a series on American industrial titans, this episode focuses specifically on Rockefeller’s impact on the business world.

John D. Rockefeller History

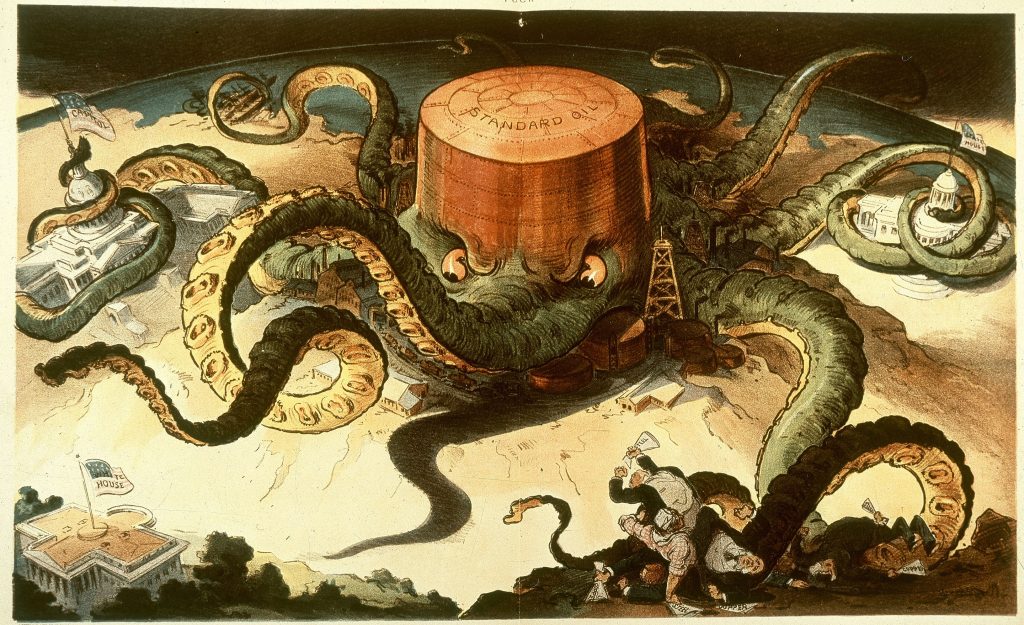

Rockefeller as an industrial emperor, 1901 cartoon from Puck magazine

(Wiki Image by Puck (magazine). Uploaded to Wikipedia by en:User: Rjensen – the English language Wikipedia (log), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4374648)

John D. Rockefeller (1839–1937) was an American industrialist and philanthropist who became one of the wealthiest people in history by revolutionizing the oil industry. His career is a classic example of both the cutthroat capitalism of the Gilded Age and the rise of modern, systematic philanthropy.

Early Life and Business Acumen

Born in Richford, New York, Rockefeller came from humble beginnings. He moved with his family to Cleveland, Ohio, where he took a job as a bookkeeper at age 16. Even in his youth, he was known for his meticulous record-keeping and business savvy, saving his money and giving a portion to his church and various charities, a practice he would continue throughout his life. At age 20, he started his own commission business dealing in grain and other goods.

The Rise of Standard Oil

Sensing the potential of the burgeoning oil industry in western Pennsylvania, Rockefeller entered the refining business in 1863. He quickly recognized that the key to profitability was not in drilling for oil, which was a chaotic and unpredictable process, but in controlling the refining, transportation, and distribution of the finished product, kerosene. In 1870, he founded the Standard Oil Company of Ohio with his brother William, Henry Flagler, and other partners.

Rockefeller and his associates employed a series of aggressive and often ruthless business tactics to gain a near-total monopoly on the oil industry. These included:

- Acquiring Competitors: He would systematically buy out rival refineries, often offering them a choice between joining Standard Oil or being driven out of business.

- Railroad Rebates: He secretly negotiated favorable rates from railroads, which made it impossible for his competitors to ship their oil at a profitable price.

- Trusts: In 1882, he organized the Standard Oil Trust, the first major business trust in the U.S. This legal structure allowed him and a board of trustees to control dozens of affiliated companies, effectively giving him a monopoly on 90% of U.S. oil refining and marketing by the 1880s.

Public Scrutiny and Dissolution

Rockefeller’s enormous wealth and business practices made him a target of public criticism. “Muckraking” journalists, most famously Ida Tarbell in her book The History of the Standard Oil Company, exposed the company’s predatory tactics and collusion with railroads. This widespread public hostility contributed to the passage of antitrust laws, such as the Sherman Antitrust Act. In 1911, the U.S. Supreme Court found Standard Oil to be in violation of these laws and ordered it to be broken up into 34 separate entities. Ironically, this breakup made Rockefeller even richer, as the individual stock prices of the new companies soared. He became the country’s first billionaire.

Legacy of Philanthropy

As Rockefeller retired from the day-to-day management of his empire, he turned his attention to philanthropy with the same systematic intensity he had applied to business. He was heavily influenced by the philosophy of his advisor, Frederick T. Gates, who encouraged him to move beyond simple charity and address the root causes of major problems. This led him to establish several landmark philanthropic institutions, which pioneered a new, data-driven approach to giving:

- The Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (1901): Now Rockefeller University, it was one of the first biomedical research centers in the U.S.

- The General Education Board (1902): Worked to improve education, particularly in the American South, for both African Americans and whites.

- The Rockefeller Foundation (1913): A global organization dedicated to promoting “the well-being of mankind throughout the world.” It was instrumental in the near-eradication of hookworm in the American South and yellow fever in the U.S.

Rockefeller died in 1937 at the age of 97, having given away more than $500 million during his lifetime. His twin legacies as a ruthless monopolist and a pioneering philanthropist continue to define discussions of American capitalism and charity.

John D. Rockefeller: Early Life and Business Acumen

Rockefeller, c. 1872, shortly after founding Standard Oil

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – https://books.google.com/books?id=zaYZAAAAYAAJ, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11340931)

John D. Rockefeller’s legendary business acumen was forged in the crucible of a challenging and formative early life. His upbringing instilled in him a unique combination of discipline, piety, and a relentless drive for efficiency and profit.

Humble Beginnings and Formative Influences

John Davison Rockefeller was born on July 8, 1839, in Richford, New York. His childhood was marked by stark contrasts, largely due to his father, William “Big Bill” Rockefeller, a traveling salesman and con artist who was often absent for long periods. This instilled in young John a sense of responsibility and a desire for stability.

In contrast, his mother, Eliza Davison Rockefeller, was a devout Baptist who instilled in her son a strong sense of frugality, discipline, and religious faith. From a young age, John was taught the value of hard work and careful financial management. A famous anecdote tells of him raising turkeys and keeping a detailed ledger of his profits, a practice that foreshadowed his meticulous attention to detail in his later business dealings.

First Steps into the Business World

In 1853, the Rockefeller family moved to the Cleveland, Ohio area. Rather than attending college, a teenage John D. enrolled in a local commercial college for a three-month course in bookkeeping. This practical education proved invaluable.

At the age of 16, he landed his first job as an assistant bookkeeper for Hewitt & Tuttle, a commission merchant firm in Cleveland. He approached this role with extraordinary seriousness and dedication, meticulously tracking every cent. He famously referred to his first day of work, September 26, 1855, as “Job Day” and celebrated it annually for the rest of his life. It was here that he honed his skills in cost analysis and developed an almost religious reverence for numbers and financial ledgers.

The Genesis of a Business Magnate

Rockefeller’s early business ventures showcased the core tenets of his emerging business philosophy:

- Calculated Risk-Taking: In 1859, at the age of 20, he and a partner, Maurice B. Clark, went into the commission merchant business for themselves. They raised $4,000 in capital (a significant sum at the time), with Rockefeller contributing his life savings of just under $1,000. This was a calculated risk, based on his thorough understanding of the business from his time at Hewitt & Tuttle.

- Seizing Opportunity: The outbreak of the Civil War created immense demand for agricultural products and other goods. The firm of Clark & Rockefeller profited handsomely by supplying the Union army. This experience taught Rockefeller the importance of recognizing and capitalizing on large-scale economic trends.

- A Vision for the Future: While his commission business was successful, Rockefeller saw an even greater opportunity in the nascent oil industry following the discovery of oil in nearby Pennsylvania. He understood that the real money wasn’t in drilling for oil—a chaotic and speculative endeavor—but in refining it. In 1863, he and his partners invested in their first oil refinery in Cleveland’s “Flats.” This marked his pivot towards the industry he would come to dominate.

Rockefeller’s early life and first business experiences were instrumental in shaping the man who would build the Standard Oil monopoly. The discipline learned from his mother, the meticulousness from his bookkeeping training, and the strategic foresight gained from his early ventures all coalesced to create one of the most formidable business minds in history. He was a master of efficiency, a shrewd negotiator, and had an unwavering focus on the bottom line, all traits that were evident long before he became the world’s richest man.

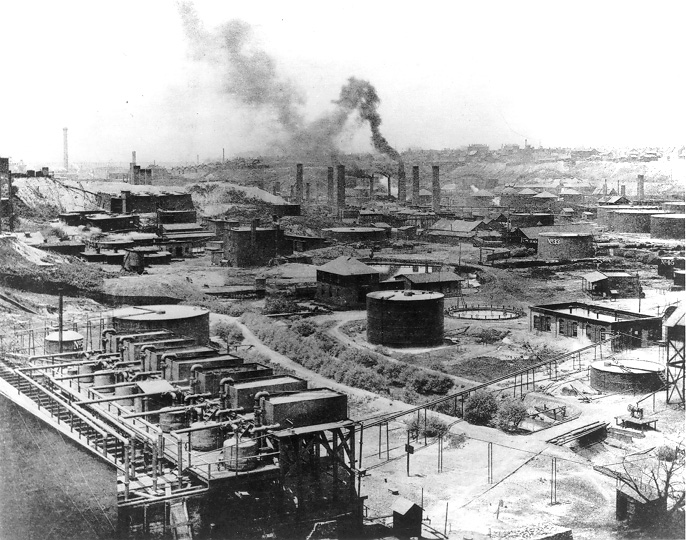

John D. Rockefeller: The Rise of Standard Oil

Standard Oil Refinery No. 1 in Cleveland, Ohio, 1897

(Wiki Image By http://ech.cwru.edu/ech-cgi/article.pl?id=BA, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=507193)

John D. Rockefeller’s creation of Standard Oil is a story of strategic brilliance, ruthless efficiency, and the relentless pursuit of market domination. Through a combination of savvy business practices and an unwavering focus on control, he built an industrial empire that reshaped the American economy.

From Refinery to Monopoly

The journey began in 1870 when Rockefeller, along with his brother William Rockefeller, Henry Flagler, Samuel Andrews, and Stephen Harkness, incorporated the Standard Oil Company in Ohio. At the time, the oil industry was chaotic and fragmented, with hundreds of small, inefficient refineries competing fiercely. Rockefeller saw an opportunity to bring “order” to the industry, with his company setting the “standard” for quality and efficiency.

Standard Oil’s initial strategy was one of horizontal integration, meaning it focused on acquiring or driving out its competitors in the refining sector. Rockefeller’s approach was methodical and highly effective:

- The Sell-or-Perish Proposition: He would systematically approach the owners of other Cleveland refineries and offer to buy them out. He would open his meticulously kept books to show them the profits they could make by joining him or the inevitable losses they would suffer by competing against his highly efficient operation.

- The Cleveland Massacre: This strategy culminated in a period in 1872 where, in a matter of weeks, Standard Oil acquired 22 of its 26 main competitors in Cleveland. This single move gave the company immense control over one of the nation’s primary refining centers.

The Octopus Spreads Its Tentacles 🐙

With a dominant position in refining secured, Rockefeller expanded his control through vertical integration, taking over every step of the oil production process. This allowed Standard Oil to control costs and logistics in a way no competitor could match.

Key elements of this vertical integration included:

- Transportation Dominance: Rockefeller recognized that controlling transportation was key to controlling the industry. He negotiated secret, preferential rebates from the railroads, which not only lowered his shipping costs but also raised the costs for his competitors. When railroads became less competitive, Standard Oil invested heavily in building a vast network of pipelines. This technological innovation allowed it to transport crude oil far more cheaply and efficiently.

- Control Over the Supply Chain: The company acquired its forests for lumber to make barrels, built its own barrel-making plants, and purchased fleets of railroad tank cars. This deep integration insulated Standard Oil from price fluctuations and supply disruptions from external suppliers.

The Standard Oil Trust and Public Backlash

To manage this sprawling empire and circumvent state laws that restricted corporations from owning stock in other companies, Rockefeller and his associates pioneered the trust model in 1882. The Standard Oil Trust was a legal arrangement where shareholders of various affiliated companies turned over their stock to a board of trustees, effectively creating a single, massive, centrally controlled monopoly.

By the 1880s, Standard Oil controlled roughly 90% of the U.S. oil refining capacity. This near-total dominance led to widespread public condemnation. The company was famously depicted in political cartoons as a menacing octopus, its tentacles encircling the machinery of government, commerce, and daily life.

This public outcry eventually led to government action, culminating in the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. While it took many more years of legal battles, the rise of Standard Oil and the public’s reaction to its monopolistic power fundamentally changed the relationship between government and big business in America, ultimately leading to the landmark Supreme Court decision in 1911 that broke up the Standard Oil empire.

John D. Rockefeller: Public Scrutiny and Dissolution

Fear of monopolies (“trusts”) is shown in this critique of Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company by Udo J. Keppler, for Puck magazine, September 7, 1904.

(Wiki Image Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=530376)

John D. Rockefeller and his company, Standard Oil, faced intense public scrutiny and were ultimately forced to dissolve due to their monopolistic practices, which crushed competition and gave them unprecedented control over the American economy.

Muckrakers and Public Outcry 🗣️

By the late 19th century, the immense power of Standard Oil had generated widespread public fear and resentment. The company was famously depicted in political cartoons as a menacing octopus, its tentacles wrapping around Congress, statehouses, and industries, symbolizing its suffocating grip on the nation.

This public anger was crystallized by a new generation of investigative journalists known as “muckrakers.” The most formidable of these was Ida Tarbell, whose father’s small oil business had been driven to ruin by Rockefeller’s tactics. Between 1902 and 1904, Tarbell published a meticulously researched and damning series of articles in McClure’s Magazine, later compiled into the book The History of the Standard Oil Company.

Her work exposed Standard Oil’s secret deals with railroads, its strategy of predatory pricing to eliminate rivals, and its overall ruthless business ethics. Tarbell’s reporting was not just an attack; it was a detailed, factual indictment that turned public opinion decisively against Rockefeller, portraying him not as a captain of industry, but as a “miser” and a monopolist.

The Government Strikes Back 🏛️

The growing public outrage translated into political and legal action. The primary weapon used against Standard Oil was the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, a federal law designed to prohibit business activities that were deemed anti-competitive.

For years, Standard Oil used its army of lawyers and complex corporate structure to fend off legal challenges from various states. However, the federal government, under President Theodore Roosevelt, a renowned “trustbuster,” became determined to break the company’s power.

The government’s lawsuit argued that Standard Oil’s actions constituted an “unreasonable” restraint of trade. The case methodically documented how the company had used its power to bully, intimidate, and absorb competitors to achieve and maintain its monopoly.

The Dissolution of an Empire

The legal battle culminated in the landmark 1911 Supreme Court decision in Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States. The Court ruled that Standard Oil’s business practices were in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act and had created an illegal monopoly.

The Court ordered the dissolution of the Standard Oil trust, breaking it up into 34 separate, independent companies. Some of these successor companies would become giants in their own right, including:

- Standard Oil of New Jersey (later Exxon)

- Standard Oil of New York (later Mobil)

- Standard Oil of California (later Chevron)

Ironically, the breakup of Standard Oil made John D. Rockefeller far richer than he had ever been. He retained his shares in all the newly independent companies, and as they began to compete with one another, their combined stock value soared. While the government had succeeded in breaking up his monopoly, Rockefeller’s personal fortune reached its zenith only after his empire was dismantled.

John D. Rockefeller: Legacy of Philanthropy

Some of the University of Chicago team that worked on the production of the world’s first human-caused self-sustaining nuclear reaction, including Enrico Fermi in the front row and Leó Szilárd in the second row

(Wiki Image By http://www.lanl.gov/worldview/welcome/history/08_chicago-reactor.htmlSource: en:Image:ChicagoPileTeam.png, Attribution, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=156863)

While his business practices drew intense criticism, John D. Rockefeller’s later life was defined by a visionary and transformative approach to philanthropy that established the template for large-scale, strategic giving in the 20th century. He is as much a titan of charity as he was of industry, with his contributions continuing to shape medicine, education, and scientific research across the globe.

From Tithing to Targeted Philanthropy

Rockefeller’s habit of giving was ingrained from his devout Baptist upbringing and his mother’s teaching to tithe a portion of his income. Throughout his career, he was a consistent donor to his church and various Baptist causes. However, as his fortune swelled to unprecedented levels, he became overwhelmed by pleas for assistance. This ad-hoc approach was inefficient and unsatisfying.

The pivotal shift came with the influence of Frederick T. Gates, a Baptist minister and educator whom Rockefeller enlisted in 1891. Gates urged Rockefeller to move beyond simply alleviating symptoms and instead attack the root causes of societal problems. He convinced Rockefeller to apply the same principles to philanthropy that had made Standard Oil so successful: efficiency, scalability, and a focus on data-driven, high-impact outcomes. Gates helped transform Rockefeller’s giving from a series of individual acts of charity into a systematic, “wholesale” philanthropic enterprise.

Building Institutions to Last

Under Gates’s guidance, Rockefeller’s philanthropy focused on creating and funding major, enduring institutions that could carry on their work in perpetuity. His most significant contributions include:

- The University of Chicago: In what became his first major philanthropic endeavor, Rockefeller, beginning in 1890, donated what would amount to over $35 million (a colossal sum at the time) to help establish and elevate the University of Chicago from a small Baptist college into a world-class research institution.

- The Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (now Rockefeller University): Founded in 1901, this institute was revolutionary in its focus on biomedical research to understand and cure diseases. It became a model for medical research centers worldwide and has been home to numerous Nobel laureates.

- The General Education Board (GEB): Established in 1903, the GEB was a powerful force for improving education across the United States, particularly in the South. It supported higher education, and controversially, promoted a model of “industrial education” for African Americans that emphasized manual training. The GEB also funded a massive public health campaign that was instrumental in eradicating hookworm disease in the American South.

- The Rockefeller Foundation: Chartered in 1913 with an initial endowment of $100 million, this became the flagship of Rockefeller’s philanthropic efforts, with a broad mission “to promote the well-being of mankind throughout the world.” The foundation has played a crucial role in global public health, funding the development of the yellow fever vaccine, spearheading the “Green Revolution” that boosted agricultural yields in developing nations, and supporting countless other initiatives in the arts, sciences, and humanities.

A Legacy of Scientific and Social Progress

Rockefeller’s philanthropic legacy is marked by its strategic and scientific approach. He and his advisors believed in finding “leverage points” where targeted funding could generate significant and lasting change. This is evident in their focus on:

- Public Health and Medicine: Beyond eradicating specific diseases, Rockefeller’s funding helped to professionalize and modernize medical education in the United States and abroad, establishing schools of public health at institutions like Johns Hopkins and Harvard.

- Scientific Research: His support for basic scientific inquiry provided the foundation for countless discoveries and advancements in the 20th century.

- Education: By funding universities and educational boards, he aimed to create opportunities for knowledge and advancement, albeit sometimes through a lens that reflected the racial biases of the era.

In total, John D. Rockefeller gave away over $540 million in his lifetime, a sum that, as a percentage of the national GDP, makes him arguably the most generous philanthropist in American history. While the methods by which he acquired his fortune remain controversial, the scale, vision, and enduring impact of his charitable giving created a second, and in many ways more positive, legacy that continues to benefit humanity.

John D. Rockefeller Civilization

John D. Rockefeller: Advisors

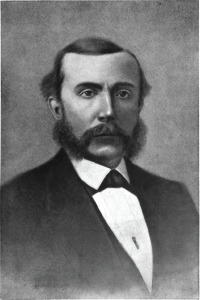

Portrait of Henry Flagler

(Wiki Image By J. J. Cade – The Cyclopaedia of American biography, 1918: https://archive.org/stream/cyclopaediaofame08wilsuoft#page/n55/mode/2up, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26985744)

John D. Rockefeller, while a business genius in his own right, relied on a small circle of trusted advisors who were instrumental in both the creation of his industrial empire and the success of his philanthropic endeavors.

The Architect of the Empire: Henry Flagler तेल

Henry Morrison Flagler was not just an advisor but a co-founder and the strategic mastermind behind much of Standard Oil’s success. A fellow Ohio businessman, Flagler, joined forces with Rockefeller in 1867.

- Role and Influence: Flagler was the key negotiator and strategist. While Rockefeller was the meticulous, cost-conscious operator, Flagler was the bold visionary who devised many of the aggressive tactics that allowed Standard Oil to dominate the industry. He was instrumental in negotiating the secret, preferential rebates from the railroads that gave Standard Oil a decisive competitive advantage. His strategic thinking was central to the company’s rapid expansion and consolidation of the oil market.

The Soul of Philanthropy: Frederick T. Gates 🙏

Frederick Taylor Gates was a Baptist minister who became Rockefeller’s most important philanthropic advisor. Hired in 1891, Gates fundamentally reshaped Rockefeller’s approach to giving away his vast fortune.

- Role and Influence: Gates moved Rockefeller away from simple, ad-hoc charity and towards a model of “wholesale” philanthropy. He urged Rockefeller to apply the same principles to giving that he had to business: efficiency, scalability, and attacking the root causes of problems rather than just treating the symptoms. It was Gates who guided the creation of enduring institutions like the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (now Rockefeller University) and the Rockefeller Foundation. He provided the intellectual framework for Rockefeller’s philanthropy, transforming it from a personal endeavor into a scientific and systematic enterprise aimed at promoting human progress on a global scale.

Other Key Figures

While Flagler and Gates were his most influential advisors, other key figures played important roles:

- John D. Rockefeller Jr.: Rockefeller’s son, “Junior,” became a crucial advisor in his father’s later years, particularly in overseeing and professionalizing the family’s philanthropic activities. He was instrumental in the day-to-day management of the Rockefeller Foundation and other charitable institutions.

- Samuel Andrews: A brilliant chemist and one of the original partners, Andrews was the technical expert whose innovations in oil refining gave Standard Oil its initial edge in producing high-quality kerosene efficiently.

Rockefeller’s success was not a solo act. He could identify and empower brilliant advisors like Flagler and Gates, who allowed him not only to build an unprecedented industrial monopoly but also to create a philanthropic legacy that continues to shape the world today.

John D. Rockefeller: Worldwide Oil Economy

Financials

(Wiki Image By User:Rjensen – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18016866)

John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company had a significant and lasting impact on the worldwide oil economy. By consolidating the fragmented U.S. oil industry, he was able to create the first truly global oil corporation, setting precedents for international business, pricing, and distribution.

U.S. as a Global Oil Power

Before Rockefeller, the oil industry was chaotic and inefficient. Through his mastery of horizontal and vertical integration, Rockefeller brought order and stability to the industry, making the United States the leading oil producer and exporter in the world. By 1885, roughly 70% of Standard Oil’s business was conducted abroad. This dominance established the U.S. as a major player in the global economy.

Global Distribution and Pricing

Standard Oil revolutionized the global distribution of oil. It built a vast international network of pipelines, storage tanks, and distribution channels. The company’s most important product was kerosene, which became the primary source of light for millions of people worldwide. In China, for example, Standard Oil distributed lamps and sold kerosene cheaply to encourage a shift away from vegetable oils. This strategy created a massive consumer base and made China Standard Oil the largest market in Asia.

Rockefeller’s monopoly enabled the company to influence global oil prices. It often kept prices low in foreign markets to undercut competition from rivals like the Nobel family’s oil company in Baku (Russia), while charging higher prices to American consumers.

Legacy of International Rivalry

Standard Oil’s global dominance didn’t go unchallenged. Its aggressive business practices and monopolistic control led to rivalries with other emerging oil companies, particularly from Europe. These international rivalries eventually contributed to the development of the “Seven Sisters,” a group of powerful Anglo-American oil companies that dominated the global oil market for much of the 20th century. Rockefeller’s business model and the geopolitical responses to it laid the groundwork for the modern global energy market.

John D. Rockefeller: Geopolitics

John D. Rockefeller’s geopolitical impact was primarily indirect, stemming from the global reach of Standard Oil and the international influence of the Rockefeller Foundation. While he focused on his business and philanthropy, his work helped establish the United States as a dominant player in the global oil market. It influenced foreign policy through his family’s subsequent generations.

Standard Oil’s Global Reach

- Export Dominance: Standard Oil was described as the world’s first truly global corporation. By the late 19th century, roughly 70% of its business was conducted abroad. It sold kerosene worldwide, providing light to millions in Europe, Asia, and beyond. This global dominance helped establish the U.S. as a major economic power on the international stage.

- A Catalyst for Competition: Standard Oil’s monopolistic presence in foreign markets was not without its challenges. It often faced competition from European oil companies, some of which had close ties to their respective governments. This rivalry over global oil markets became a significant factor in international economic relations.

The Rockefeller Foundation’s International Influence

After retiring from business, Rockefeller used his wealth to establish the Rockefeller Foundation in 1913. This institution had a profound geopolitical impact through its work in public health, education, and science.

- Global Public Health: The foundation’s International Health Division conducted extensive campaigns to combat diseases like hookworm and yellow fever in dozens of countries. This work not only improved public health but also served as a form of “soft power,” boosting America’s international reputation and influence.

- The Green Revolution: The Rockefeller Foundation’s agricultural development program in Mexico in the 1940s helped to create the “Green Revolution,” a series of research and technology initiatives that dramatically increased agricultural production worldwide. This effort had a massive impact on global food security.

The Rockefeller Family’s Legacy in Foreign Policy

While John D. Rockefeller’s direct involvement in geopolitics was limited, his descendants became deeply involved in American foreign policy and international relations. For example, his grandson Nelson Rockefeller served as Vice President. He held various roles in the State Department, and his grandson, David Rockefeller, became a prominent figure in international banking and foreign affairs. They continued to use their wealth and influence to shape global policy through institutions like the Council on Foreign Relations and the Trilateral Commission.

John D. Rockefeller: Law

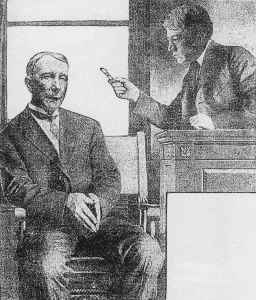

Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis wags his pen at John D. Rockefeller, who is sitting in the witness stand, during the Standard Oil case on July 6, 1907.

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – Microfilm image reproduced in Landis, Lincoln (2006) From Pilgrimage to Promise: Civil War Heritage and the Landis Boys of Logansport, Indiana, Maryland, United States: Heritage Books, pp. 131 ISBN: 0-7884-3831-X., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15447161)

Legal and political challenges defined John D. Rockefeller’s business career. His company, Standard Oil, became a prime target for antitrust legislation, which ultimately led to the company being broken up by the Supreme Court.

The Rise of the Trust and Antitrust Challenges

Rockefeller’s legal challenges stemmed from his monopolistic practices. In 1882, he created the Standard Oil Trust to consolidate his numerous business holdings. This trust was a new legal arrangement that allowed a small group of trustees to manage a vast network of companies as a single entity, effectively circumventing laws that prohibited a corporation from owning stock in another.

This powerful new corporate structure, combined with his ruthless business tactics, such as securing secret railroad rebates and predatory pricing, led to public outcry. Critics argued that Standard Oil was stifling competition, controlling prices, and wielding undue political influence.

The Sherman Antitrust Act and the Supreme Court

The backlash against monopolies like Standard Oil prompted the U.S. government to act. In 1890, Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act, the first federal law to prohibit monopolies and “every contract, combination… or conspiracy, in restraint of trade.”

For over a decade, the government and various states used the law to challenge Standard Oil. The legal battle culminated in the landmark 1911 Supreme Court case, Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States. The court ruled that Standard Oil had indeed engaged in “unreasonable” restraint of trade and had to be dissolved. The court’s decision was a major victory for the federal government and established a precedent for regulating corporate power. The ruling broke up Standard Oil into 34 separate, independent companies, including the precursors to modern-day ExxonMobil and Chevron.

Political Cartoons

Public sentiment against Standard Oil was often captured in political cartoons of the era. A common visual metaphor was the “Standard Oil Octopus,” with its tentacles wrapped around the U.S. Capitol, the White House, and other industries, symbolizing the company’s immense and unchecked influence over the government and economy.

John D. Rockefeller: Political People

The big corporations, such as Standard Oil, made large contributions in 1896 to McKinley’s presidential campaign, managed by Mark Hanna.

(Wiki Image Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17913435)

Yes, John D. Rockefeller had significant interactions with political figures, both as allies who protected his interests and as adversaries who sought to dismantle his monopoly.

John D. Rockefeller’s relationship with the political world was complex and often contentious. While he personally avoided the political spotlight, his company, Standard Oil, was a powerful force that actively sought to influence politicians and policy to protect its vast business empire. At the same time, this immense power made him a prime target for ambitious, reform-minded political figures.

Cultivating Political Allies 🤝

To protect its interests, Standard Oil engaged in extensive lobbying and provided financial support to political campaigns. The goal was to elect friendly politicians who would resist calls for regulation and antitrust action. Key allies included:

- Senator Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island: A powerful and influential Republican senator, Aldrich was a staunch defender of big business and a key ally of Standard Oil in Congress. His daughter, Abby Aldrich, married John D. Rockefeller Jr., further cementing the close ties between the two families.

- Mark Hanna: A U.S. Senator and the powerful chairman of the Republican National Committee, Hanna was a master political strategist who orchestrated William McKinley’s presidential campaigns. He was a strong proponent of business interests, and his political machine benefited from the support of corporations like Standard Oil.

These relationships helped ensure that for many years, the federal government maintained a hands-off approach to regulating Standard Oil’s business practices.

Political Adversaries and “Trust-Busting” 🤺

As Standard Oil’s monopoly grew, so did public resentment and the number of political opponents who saw the company as a threat to democracy and free-market competition. The “trust-busting” movement gained momentum, led by several key figures:

- President Theodore Roosevelt: While he distinguished between “good” and “bad” trusts, Roosevelt’s administration initiated the federal lawsuit under the Sherman Antitrust Act that ultimately led to the breakup of Standard Oil. Roosevelt’s public persona as a “trust-buster” was largely defined by his administration’s fight against Rockefeller’s empire.

- Ida Tarbell: Though not a politician, the investigative journalism of this “muckraker” was profoundly political. Her meticulously researched exposé, The History of the Standard Oil Company, provided the public and politicians with the ammunition needed to build the case against the company, turning public opinion into an unstoppable political force.

The political battles surrounding Standard Oil were a defining feature of the Gilded Age and the subsequent Progressive Era. They highlighted the growing tensions between immense corporate power and the role of government, ultimately leading to landmark legal and political precedents that reshaped the relationship between business and politics in America.

John D. Rockefeller: Rich and Poor

John D. Rockefeller had a complex view of the relationship between the rich and the poor, which evolved over his life. He believed in a form of social Darwinism, where wealth was a sign of hard work and divine favor, but he also came to believe that the wealthy had a moral obligation to use their fortunes to benefit society.

Rockefeller’s Views on Wealth and Poverty

- Divine Providence: Rockefeller was a devout Baptist who believed that his ability to make money was a “gift of God.” He saw his immense wealth not as a personal achievement but as a blessing to be used for the “good of mankind.” This belief led him to separate his business tactics from his personal and charitable life. He was able to be a ruthless businessman on one hand and a dedicated philanthropist on the other.

- Meritocracy: Rockefeller believed that wealth was a direct result of hard work, thrift, and a sound character. He was not concerned with the wide gap between the rich and the poor, seeing it as part of a natural, God-given order. He believed that if a man was poor, it was often due to a lack of these virtues.

- “Wise Giving”: While he gave away a massive fortune, Rockefeller was critical of what he saw as “indiscriminate charity” that simply gave money to the poor. He believed this was a harmful practice that could encourage idleness. Instead, he pioneered a new, systematic approach to philanthropy, focusing on what he called “root causes.” He sought to create institutions that would help people help themselves, primarily through education, scientific research, and public health initiatives.

Economic Impact and the Rich-Poor Gap

On one hand, Rockefeller’s business practices contributed to a widening of the rich-poor gap during the Gilded Age. His monopolistic control of the oil industry crushed smaller competitors, and his immense wealth stood in stark contrast to the low wages and poor working conditions of many of his employees.

However, his later philanthropic work was a direct attempt to address some of the problems created by industrial capitalism, such as disease and lack of educational opportunities. His foundations, such as the University of Chicago and the Rockefeller Foundation, provided numerous opportunities and played a crucial role in addressing major public health crises.

This video explores how Rockefeller’s mindset on wealth allowed him to become the richest man in history. Secrets The Rich Use That The Poor Don’t Know | John D. Rockefeller

John D. Rockefeller: Science

Hookworm life cycle

(Wiki Image By The original uploader was Sonett72 at English Wikipedia. – CDC – Department of Parasitic Diseaseshttp://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/ImageLibrary/Hookworm_il.htmhttp://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/images/ParasiteImages/G-L/Hookworm/Hookworm_LifeCycle.gifOriginally from en.wikipedia; description page is/was here., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1860052)

John D. Rockefeller was a pivotal figure for science in two fundamental ways: first, by applying scientific principles to build his oil empire, and second, by using his immense fortune to create the institutional framework for modern scientific medicine.

Science for Profit: The Standard Oil Machine 🧪

While not a scientist himself, Rockefeller was a master at applying scientific methods to business. At a time when many industries relied on guesswork, Standard Oil was built on a foundation of chemistry and efficiency.

- Refining and Chemistry: Standard Oil hired professional chemists to analyze crude oil and systematically improve the refining process. Their primary goal was to maximize the yield of high-value kerosene, the main product used for lighting.

- Waste as a Byproduct: The company’s chemists were also tasked with finding uses for the materials left over from refining. They turned this industrial “waste” into a massive source of profit by developing and marketing over 300 different products, including petroleum jelly (Vaseline), paraffin wax for candles, and gasoline, which was initially considered a useless byproduct.

Philanthropy for Science: Building Modern Medicine 🔬

Rockefeller’s most enduring scientific legacy comes from his revolutionary philanthropy, which was guided by his advisor, Frederick T. Gates. Gates convinced Rockefeller to move beyond traditional charity and instead attack the root causes of human suffering through scientific research.

- The Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (1901): This was his flagship scientific project. Rockefeller founded this institute (now Rockefeller University) in New York City as a dedicated place where scientists could conduct fundamental research into the underlying causes of disease, free from the demands of teaching or treating patients. It became the model for modern biomedical research centers and has been home to dozens of Nobel Prize winners.

- Eradicating Disease: Through his foundations, Rockefeller funded the first large-scale public health campaigns based on scientific evidence. The most famous example was the successful effort to eradicate hookworm in the American South. This wasn’t just about handing out medicine; it was a systematic campaign involving mapping infection zones, treatment, education, and prevention.

- Funding Universities: His massive donations to the University of Chicago helped transform it into a world-class research institution that would become a leader in numerous scientific fields, including physics, where the first self-sustaining nuclear reaction was achieved.

Rockefeller’s approach was to use his wealth to build permanent, professional institutions that would advance scientific knowledge long after he was gone, a model that has influenced major foundations ever since.

John D. Rockefeller: Technology

Samuel Andrews (1836-1904) was a chemist and inventor.

(Wiki Image By Unknown photographer – Munsey’s Magazine. Vol. 47, no. 1. April, 1912, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=161533620)

John D. Rockefeller’s success was fundamentally intertwined with the strategic use and control of technology in the burgeoning oil industry. While not an inventor himself, his genius lay in recognizing, acquiring, and standardizing the most efficient technologies to dominate the market.

Refining and Byproducts 🧪

The most critical technology for Rockefeller’s Standard Oil was oil refining. In the late 19th century, the primary product from crude oil was kerosene for lighting. Early refining processes were inefficient and dangerous, often wasting a significant portion of the crude oil.

Rockefeller’s key strategies included:

- Hiring Experts: He brought in the best chemists and engineers, like Samuel Andrews, to squeeze every last drop of value from a barrel of crude oil.

- Waste Utilization: Standard Oil’s refineries were at the forefront of developing ways to use the “waste” products from kerosene refining. They developed over 300 different products, including:

- Gasoline: Initially a volatile byproduct dumped into rivers, it later became the fuel for the internal combustion engine.

- Paraffin wax: Used for making candles.

- Vaseline: A petroleum jelly for medical and cosmetic purposes.

- Lubricating oils: Essential for the machinery of the Second Industrial Revolution.

This focus on efficiency and byproduct utilization dramatically lowered his costs and allowed him to undercut competitors.

Transportation and Logistics 🚂

Controlling the transportation of oil was just as crucial as refining it—Rockefeller leveraged technology to create a ruthlessly efficient logistics network.

- Pipelines: While initially relying on railroads, Rockefeller quickly saw the potential of pipelines to move crude oil cheaply and directly from the well to the refinery. Standard Oil invested heavily in building a vast network of pipelines, which gave it a massive competitive advantage. They could bypass the railroads, which they had previously strong-armed into giving them preferential rates and rebates.

- Railroad Tank Cars: Before pipelines, oil was transported in leaky wooden barrels. Standard Oil pioneered the use of cylindrical, iron railroad tank cars, which were safer, cheaper, and held more oil: this innovation standardized oil transport and further reduced costs.

Control Through Technology

For Rockefeller, technology was a tool for achieving economies of scale. By standardizing equipment and processes across all his refineries and transportation networks, he created an assembly line-like efficiency. If a part broke at one refinery, a standardized replacement from another could be quickly installed, minimizing downtime. This level of integration and standardization was unprecedented and allowed Standard Oil to control an estimated 90% of the U.S. oil market at its peak. His technological dominance was a key factor in the creation of his monopoly.

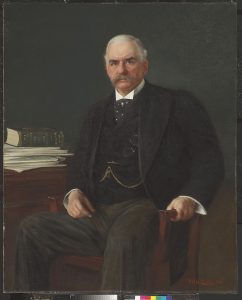

Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919): The Steel Magnate

Carnegie, c. 1913

(Wiki Image By Theodore C. Marceau – Library of Congress, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=168476589)

Andrew Carnegie Quotes

Andrew Carnegie was a prolific writer and speaker, and his quotes often reflect his “Gospel of Wealth” philosophy, which stressed that the rich had a moral obligation to use their fortunes to benefit society. He also offered many insights on business, success, and hard work.

Here are some of his most famous quotes:

On Wealth and Philanthropy:

- “The man who dies rich, dies disgraced.”

- “This, then, is held to be the duty of the man of wealth: to set an example of modest, unostentatious living, shunning display or extravagance; to provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent upon him; and, after doing so, to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to administer, and strictly bound as a matter of duty to administer in the manner which, in his judgment, is best calculated to produce the most beneficial results for the community—the man of wealth thus becoming the mere trustee and agent for his poorer brethren, bringing to their service his superior wisdom, experience, and ability to administer, doing for them better than they would or could do for themselves.” (From The Gospel of Wealth)

- “The best way of doing good to the poor is not to give them money, but to give them the means of helping themselves.”

- “Surplus wealth is a sacred trust which its possessor is bound to administer in his lifetime for the good of the community.”

On Business and Success:

- “The secret of success is to do the common things uncommonly well.”

- “The way to become rich is to put all your eggs in one basket and then watch that basket.”

- “You cannot push any one up a ladder unless he be willing to climb a little himself.”

- “Do your duty and a little more and the future will take care of itself.”

- “I resolved to stop accumulating and begin the infinitely more serious and difficult task of wise distribution.”

- “No man will make a great leader who wants to do it all himself or get all the credit for doing it.”

On Life and Wisdom:

- “As I grow older, I pay less attention to what men say. I just watch what they do.”

- “There is little success where there is little laughter.”

- “There is no class so pitiably wretched as that which possesses money and nothing else.”

- “A library outranks any other one thing a community can do to benefit its people. It is a never failing spring in the desert.”

- “He that cannot reason is a fool. He that will not is a bigot. He that dare not is a slave.”

A Chronology of Andrew Carnegie’s Life

Andrew Carnegie’s life is a classic “rags-to-riches” story, a journey from a poor Scottish immigrant to the world’s wealthiest man, and finally to a renowned philanthropist. His chronology can be broken down into three key periods: his humble beginnings, his rise as a steel magnate, and his years dedicated to philanthropy.

Early Life and Rise to Success

- 1835: Andrew Carnegie is born in Dunfermline, Scotland, to a family of handloom weavers.

- 1848: Facing economic hardship, his family immigrates to Allegheny, Pennsylvania, a bustling industrial town near Pittsburgh.

- 1849: Carnegie gets his first job as a bobbin boy in a cotton mill for $1.20 a week. He soon becomes a messenger boy for a telegraph office.

- 1853: He is hired by Thomas A. Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad as a telegrapher and personal assistant, a position that gives him invaluable experience in business and management.

- 1865: Carnegie leaves the Pennsylvania Railroad to focus on his growing investments, particularly in the iron industry. He founded the Keystone Bridge Company, which specializes in iron bridges.

- 1868: Carnegie writes a personal memo to himself, pledging to retire at age 35 to pursue a life of public service and education, a goal he would not fully achieve for more than 30 years.

The Steel Empire

- 1873: Carnegie shifts his focus to the steel industry, founding his first steel mill near Pittsburgh. He adopts the new Bessemer process, which allows for the mass production of steel, making him a leader in the industry.

- 1889: Carnegie publishes his famous essay, “The Gospel of Wealth,” in which he argues that the rich have a moral obligation to use their fortunes to improve society.

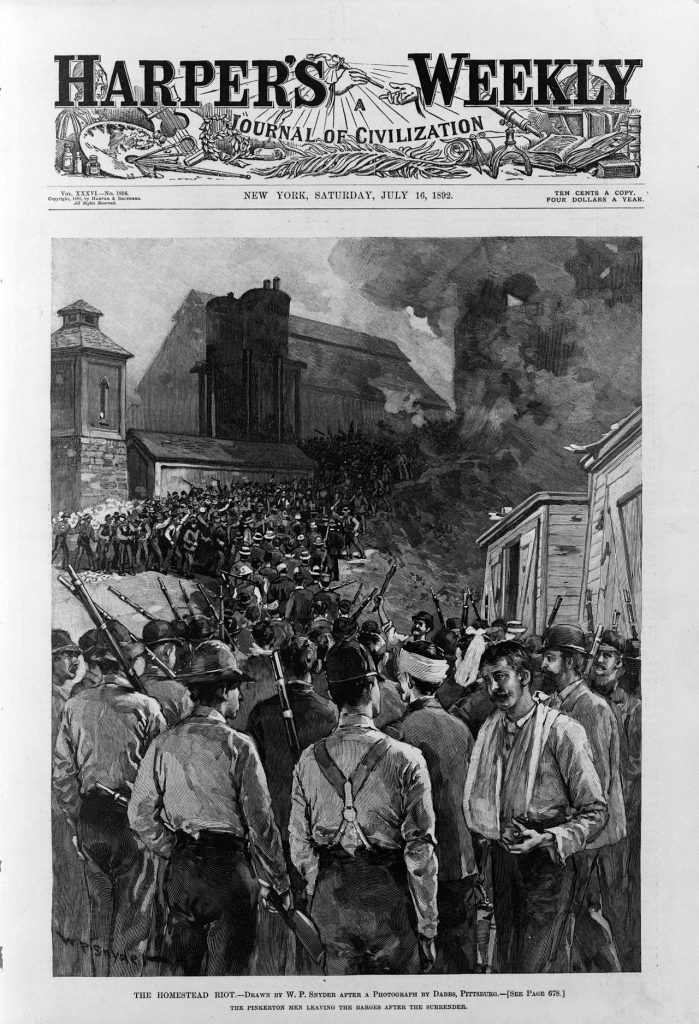

- 1892: Carnegie’s various business holdings are consolidated into the Carnegie Steel Company, which becomes the largest steel company in the world. This is also the year of the controversial Homestead Strike, a violent labor dispute at one of his plants.

Philanthropy and Legacy

- 1901: At age 66, Carnegie sells Carnegie Steel to banker J.P. Morgan for about $480 million, making him the richest man in the world. Morgan merges it with other companies to form U.S. Steel, the world’s first billion-dollar corporation.

- 1901–1919: Carnegie dedicates the rest of his life to philanthropy, giving away more than $350 million. He funds the construction of over 2,500 public libraries, founds Carnegie Mellon University, and establishes several trusts, including the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- 1919: Andrew Carnegie dies on August 11 at his estate in Massachusetts, having given away almost 90% of his fortune.

Andrew Carnegie YouTube Video

How Andrew Carnegie Became The Richest Man In The World

- Views: 3.9 Million

- Channel: Business Casual

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LNYkor8IDoA

- Description: This highly-viewed video provides a concise and engaging overview of Carnegie’s “rags-to-riches” story and his business strategies.

Andrew Carnegie Documentary: One Of The Wealthiest People of All Time.

- Views: 297,000

- Channel: Tounce AI

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JQI5ozFdNYs

- Description: A feature-length documentary that offers a deep dive into Carnegie’s life, from his impoverished childhood in Scotland to becoming a titan of industry.

ANDREW CARNEGIE AND NAPOLEON HILL DOCUMENTARY-PART ONE

- Views: 393,000

- Channel: Gary Chappell

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67mLCtTjwGg

- Description: This documentary explores the connection and philosophical alignment between Andrew Carnegie and Napoleon Hill, author of “Think and Grow Rich.”

Man of Steel: Andrew Carnegie | The Gilded Age

- Views: 114,000

- Channel: American Experience | PBS

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vmbRtjN0gAk

- Description: A short clip from the acclaimed PBS series “The Gilded Age” that introduces Andrew Carnegie as a central figure of the era.

Andrew Carnegie’s 20 Laws of Power

- Views: 7,700

- Channel: Napoleonism

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fQXjotQbf9o

- Description: This video analyzes the strategies and principles that Andrew Carnegie used to build his power and influence in the business world.

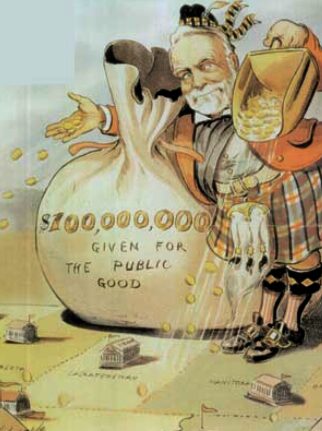

Andrew Carnegie History

Andrew Carnegie’s philanthropy. Puck magazine cartoon by Louis Dalrymple, 1903

(Wiki Image By Louis Dalrymple. – Puck Magazine June 1, 1903, published in New York City, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25860051)

Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist who led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century, becoming one of the richest Americans in history. His life is a classic “rags-to-riches” story, a testament to the opportunities of the Gilded Age, and a case study in the contradictions of capitalism and philanthropy.

Early Life and Rise to Riches

Born into a family of handloom weavers in Dunfermline, Scotland, Carnegie’s life took a drastic turn when the rise of industrial steam threatened his family’s livelihood looms. In 1848, at the age of 12, his family immigrated to Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh), to seek a new life.

Carnegie’s formal education was cut short, and he began working as a bobbin boy in a cotton mill, earning just $1.20 a week. His ambition and hard work quickly propelled him upward. He moved on to a job as a telegraph messenger boy, where he taught himself telegraphy and memorized the faces of important businessmen. This led him to a pivotal role as the personal secretary and telegrapher for Thomas A. Scott, the superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s western division.

While working for the railroad, Carnegie’s keen eye for opportunity led him to make several shrewd investments in ventures like oil companies and sleeping cars. By the time he left the railroad in 1865, he had already amassed a considerable fortune.

The Steel Empire

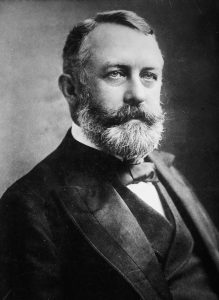

In the 1870s, Carnegie focused his attention on the burgeoning steel industry. He was one of the first to recognize the potential of the new Bessemer process for mass-producing steel cheaply and efficiently. He established the J. Edgar Thomson Steel Works (later becoming the Carnegie Steel Company) in Pittsburgh, which quickly became a dominant force in the industry.

Carnegie’s business strategy, known as vertical integration, was highly effective. He controlled every stage of the steel production process, from owning the iron ore mines and coal fields to operating the railroads and ships that transported the raw materials. This allowed him to cut costs and outcompete rivals, making his company the largest steel manufacturer in the world.

However, his business success came at a heavy cost to his workers. Carnegie was a fierce opponent of labor unions, and his company’s policies led to long hours, low wages, and dangerous working conditions. The most infamous incident was the Homestead Strike of 1892, where Carnegie’s manager, Henry Clay Frick, hired armed Pinkerton guards to break a strike, resulting in a violent confrontation that left several people dead.

The “Gospel of Wealth” and Philanthropy

In 1901, at the age of 65, Carnegie sold his company to banker J.P. Morgan for $480 million, creating the U.S. Steel Corporation. This sale made him one of the wealthiest people in the world. He then dedicated the rest of his life to a cause he had articulated in his famous 1889 essay, “The Gospel of Wealth.”

In this essay, Carnegie argued that the wealthy had a moral obligation to use their surplus fortune to improve society. He famously wrote, “The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.” He believed that giving money away indiscriminately would be a waste. Instead, the rich should act as “trustees” of their wealth, using it strategically to create opportunities for the less fortunate to help themselves.

Carnegie’s philanthropy was monumental in scale:

- He funded the establishment of over 2,500 public libraries around the world, providing access to knowledge and self-improvement for all.

- He endowed institutions dedicated to science, education, and world peace, many of which still exist today, including the Carnegie Institution for Science, Carnegie Mellon University, and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- He also funded the construction of Carnegie Hall in New York City and gave thousands of organs to churches worldwide.

By the time of his death in 1919, he had given away over $350 million (the equivalent of more than $10 billion in today’s currency), nearly 90% of his fortune, solidifying his legacy as both a ruthless industrialist and a pioneering philanthropist.

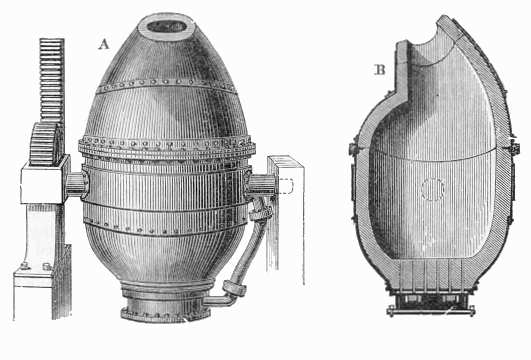

Andrew Carnegie: Early Life and Rise to Riches

Bessemer converter

(Wiki Image Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=91836)

Andrew Carnegie’s life is a quintessential “rags-to-riches” story, tracing his journey from a poor immigrant to one of the wealthiest and most influential figures of the Gilded Age.

From Dunfermline to Allegheny

Andrew Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland, in 1835. His father was a skilled weaver, but the Industrial Revolution and the rise of steam-powered looms made his trade obsolete, plunging the family into poverty. Seeking a better life, the Carnegies immigrated to the United States in 1848 and settled in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh).

At just 13 years old, Carnegie began working as a bobbin boy in a cotton mill, earning a meager $1.20 a week. This experience of hard labor fueled his ambition to climb out of poverty. He soon moved on to a job as a telegraph messenger, a role that proved to be a pivotal turning point.

The Telegraph and the Railroad: Ladders of Success 🪜

Working for the O’Reilly Telegraph Company, Carnegie quickly distinguished himself with his incredible memory and work ethic. He memorized the streets and businesses of Pittsburgh and could recognize the sounds of incoming messages by ear. This caught the attention of Thomas A. Scott, a superintendent at the Pennsylvania Railroad, who hired Carnegie as his personal telegraph operator and private secretary in 1853.

Under Scott’s mentorship, Carnegie received an invaluable education in business and management. He learned how to run a complex organization, manage finances, and make critical decisions. His time at the railroad was his “business school,” and he rose rapidly through the ranks.

It was also during this period that Carnegie made his first savvy investments. With Scott’s guidance, he purchased shares in the Adams Express Company and the Woodruff Sleeping Car Company. The dividends from these investments provided him with a second stream of income and his first taste of the power of capital.

The Pivot to Iron and Steel 🌉

After the Civil War, Carnegie saw that the future lay in iron and steel. He recognized that iron bridges were replacing wooden bridges and that the nation’s rapidly expanding railroad network would require immense quantities of steel rails.

He resigned from the railroad in 1865 to focus on his ventures, founding several iron and bridge companies. His key strategy was vertical integration—controlling every step of the manufacturing process. He bought iron ore fields, coal mines, and transportation lines to ensure a steady and cheap supply of raw materials for his mills.

His defining move came in the 1870s when he adopted the Bessemer process for mass-producing high-quality steel cheaply. While others were hesitant to invest in the new technology, Carnegie went all in, building the massive Edgar Thomson Steel Works near Pittsburgh. This plant, which opened in 1875, was designed for maximum efficiency and scale, allowing him to undercut his competitors dramatically.

By constantly reinvesting profits into better technology, driving down costs, and consolidating his control over the entire supply chain, Carnegie built an industrial empire. By the 1890s, the Carnegie Steel Company was the largest and most profitable steel enterprise in the world, and Andrew Carnegie was one of the wealthiest men in history.

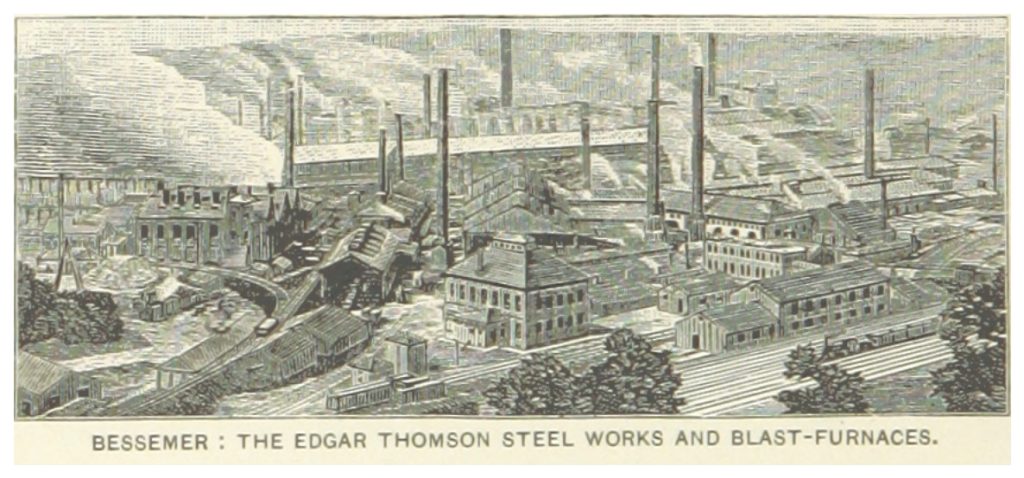

Andrew Carnegie: The Steel Empire

The Edgar Thomson Steel Works and Blast-Furnaces in Braddock, Pennsylvania (1891)

(Wiki Image By This file is from the Mechanical Curator collection, a set of over 1 million images scanned from out-of-copyright books and released to Flickr Commons by the British Library. View image on FlickrView all images from bookView catalogue entry for book., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=33557209)

Andrew Carnegie built his steel empire by relentlessly focusing on efficiency, technology, and controlling every aspect of the production process. His company, Carnegie Steel, became the largest and most profitable industrial enterprise in the world.

The Strategy: Efficiency and Integration

After leaving the Pennsylvania Railroad, Carnegie dedicated himself to the iron and steel industry. His core business philosophy revolved around two key principles:

- Constant Reinvestment in Technology: Carnegie was an early and enthusiastic adopter of the Bessemer process, a new method for mass-producing high-quality steel cheaply and efficiently. While competitors hesitated, he built the massive Edgar Thomson Steel Works in the 1870s, specifically designed to leverage this new technology. He was famous for his motto, “Watch the costs, and the profits will take care of themselves,” constantly scrapping old machinery for new, more efficient equipment.

- Vertical Integration: Carnegie’s true genius lay in his mastery of vertical integration. He sought to own and control every single step of the steelmaking process. His company acquired:

- Raw Materials: Iron ore mines in the Mesabi Range of Minnesota and coal fields in Pennsylvania.

- Transportation: A fleet of ships to carry ore across the Great Lakes and miles of railroad to connect the mines to the mills.

- Manufacturing: A network of the most advanced steel mills in the world.

This “ore to finished steel” control meant Carnegie Steel was not dependent on outside suppliers and could maintain ruthlessly low production costs, allowing it to undercut all competitors.

You can learn more about how Carnegie used vertical integration in his steel business by watching this video: How Did Carnegie Use Vertical Integration?

The Homestead Strike: A Dark Chapter

The relentless drive for efficiency came at a human cost. In 1892, a bitter labor dispute erupted at the company’s flagship Homestead Steel Works in Pennsylvania. While Carnegie was in Scotland, his manager, Henry Clay Frick, took a hard line against the unionized workers who were protesting wage cuts.

Frick locked the workers out and hired thousands of non-union laborers, bringing in armed Pinkerton guards to protect them. The resulting confrontation was a bloody battle, leaving at least ten men dead. The strike was ultimately broken, and it became a major stain on Carnegie’s reputation, revealing the harsh labor practices that underpinned his industrial success.

Sale and the Creation of U.S. Steel

By the turn of the century, Andrew Carnegie dominated the steel industry. His company’s profits had skyrocketed, reaching $40 million in 1900 alone (equivalent to well over $1 billion today).

Ready to retire and focus on philanthropy, Carnegie sought to sell his empire. The powerful financier J.P. Morgan, who envisioned creating a colossal steel trust, was the buyer. In 1901, in a deal famously scribbled on a piece of paper, Morgan agreed to buy Carnegie Steel for the astronomical sum of $480 million (making Carnegie the richest man in the world).

Morgan then merged Carnegie Steel with several other steel companies to create U.S. Steel, the first billion-dollar corporation in history. This marked the end of Andrew Carnegie’s reign over the steel industry and the beginning of his new career as a full-time philanthropist.

Andrew Carnegie: The “Gospel of Wealth” and Philanthropy

Carnegie with Black American leader Booker T. Washington (front row, center) in 1906 while visiting Tuskegee Institute

(Wiki Image By Frances Benjamin Johnston – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.3a10455.This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5869899)

Andrew Carnegie’s “Gospel of Wealth” was his philosophy that the rich had a moral duty to use their fortunes to advance social progress. After selling his steel empire, he dedicated his life to this cause, giving away the vast majority of his wealth in one of the greatest acts of philanthropy in history.

The “Gospel of Wealth” 📖

In 1889, Carnegie published an article titled “Wealth” (later known as “The Gospel of Wealth”) that laid out his core beliefs on the responsibilities of the wealthy. He argued that the “man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.”

His “Gospel” proposed that the fortunes of industrialists should not be passed down to heirs or given to the state upon death. Instead, he believed the wealthy should use their superior wisdom and experience to administer their fortunes for the public good during their lifetimes. He saw this as the most effective way to address societal problems and create lasting ladders of opportunity for the less fortunate.

“Ladders, Not Handouts”

Carnegie’s philanthropy was not about simple charity or handouts. He believed in providing the tools for people to improve themselves. His most famous and widespread contribution was the funding of public libraries.

He spent over $56 million to establish 2,509 libraries throughout the English-speaking world. His condition for funding was that the local community had to provide the land and agree to maintain and operate the library, ensuring it was a partnership, not a gift. He saw free access to books and knowledge as the ultimate tool for self-improvement.

A Legacy of Institutions

Beyond libraries, Carnegie’s giving was vast and created numerous enduring institutions dedicated to education, science, and world peace. The total value of his philanthropy exceeded $350 million (billions in today’s dollars).

Major institutions he founded include:

- The Carnegie Institute of Technology (now part of Carnegie Mellon University) in Pittsburgh provided technical training.

- The Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C., funds original scientific research.

- The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace aims to promote understanding and prevent armed conflict between nations.

- The Carnegie Hero Fund Commission honors and provides financial support to civilians who risk their lives to save others.

- Carnegie Hall in New York City, which he built to be one of the world’s premier performance venues.

Andrew Carnegie’s philanthropic legacy is a direct reflection of his “Gospel.” He practiced what he preached, using his immense fortune not for personal indulgence but to create a lasting infrastructure of opportunity and knowledge for generations to come.

The following video explains Carnegie’s “Gospel of Wealth” and its historical context.

The Gospel of Wealth Explained

Andrew Carnegie Civilization

Andrew Carnegie: Advisors & Influencers

Schwab in 1901 at age 39

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – Google Books – (1901). “Harnessing The Sun”. The World’s Work: p. 616. New York: Doubleday, Page, and Company., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4373214)

Andrew Carnegie, like any successful industrialist, relied on a team of trusted advisors, partners, and employees to build and manage his steel empire. His most influential advisors were Thomas A. Scott, his early mentor, and his two top executives, Henry Clay Frick and Charles M. Schwab.

Thomas A. Scott: The Mentor