Early 1800s Dinosaur Bones Chronological table

This timeline tracks the explosion of discovery in the 19th century—from the first confusing fragments found on English beaches to the industrial-scale excavation of giants in the American West.

The Century of Giants: 1800–1899

| Year | The Discovery / Event | Key Figure(s) | Significance |

| 1811 | First Ichthyosaur | Mary Anning | The 12-year-old Anning excavates the first correctly identified “Fish Lizard.” It proves that giant reptiles ruled the ancient seas. |

| 1823 | First Plesiosaur | Mary Anning | A complete skeleton with a “snake-like” neck. Georges Cuvier calls it a fake until he sees the bones. It cements Anning’s reputation. |

| 1824 | Megalosaurus Named | William Buckland | The first dinosaur ever scientifically named. Based on a jawbone, Buckland describes it as a giant, 40-foot terrestrial crocodile. |

| 1825 | Iguanodon Named | Gideon Mantell | The first herbivorous dinosaur was named. Mantell describes it by its large teeth, which resemble those of an iguana. (He mistakenly puts the thumb spike on its nose). |

| 1828 | First British Pterosaur | Mary Anning | Discovery of Dimorphodon. Proves that reptiles also ruled the air (previously only known from Germany). |

| 1833 | Hylaeosaurus Named | Gideon Mantell | The third dinosaur is named. An armored reptile demonstrates that some of these animals had spikes and shields. |

| 1842 | “Dinosauria” Coined | Richard Owen | Owen realizes Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus share fused hips. He names the group Dinosauria (“Fearfully Great Lizards”). |

| 1854 | Crystal Palace Statues | Richard Owen | The first life-sized dinosaur sculptures were unveiled in London. They are depicted as heavy, rhino-like quadrupeds that spark “Dinomania.” |

| 1858 | Hadrosaurus foulkii | Joseph Leidy | Found in New Jersey. The first nearly complete skeleton. It proves dinosaurs could stand on two legs (bipedal), shattering Owen’s “rhino” image. |

| 1861 | Archaeopteryx | Hermann von Meyer | Found in Germany. The “First Bird.” It has feathers, teeth, and a tail, providing the critical link between dinosaurs and birds. |

| 1868 | The “Head on Tail” Error | Cope vs. Marsh ⚔️ | Cope published a paper on Elasmosaurus with the head on the tail. Marsh humiliates him. The Bone Wars officially begin. |

| 1877 | The Year of Miracle | Marsh & Cope ⚔️ | A massive explosion of discovery in the American West (Morrison Formation). Marsh names Stegosaurus, Apatosaurus, and Allosaurus in quick succession. |

| 1878 | Iguanodon Bernissartensis | Belgian Coal Miners | Dozens of complete Iguanodon skeletons have been found in a Belgian mine. They prove once and for all that Iguanodons walked on two legs and the “nose horn” was a thumb spike. |

| 1879 | “Brontosaurus” Named | O.C. Marsh | Marsh describes a giant sauropod. (He famously puts the wrong skull on it, a mistake that lasts until the 1970s.) |

| 1889 | Triceratops Named | O.C. Marsh | The last great discovery of the century. Marsh identifies the massive “Three-Horned Face,” which becomes an instant icon. |

| 1897 | The Painting | Charles R. Knight | Knight paints Leaping Laelaps, capturing the new idea that dinosaurs were active, agile creatures rather than just slow lizards. |

Would you like to zoom in on a specific year, for instance, the “Year of Miracle” (1877), to see precisely how quickly Marsh was publishing papers?

Mary Anning, Richard Owen, Othniel Charles Marsh, and Edward Drinker Cope: Early Dinosaur Bones 🦴

These four figures form the foundational arc of vertebrate paleontology, spanning from coastal fossil hunting to industrial-scale dinosaur discovery—and fierce scientific rivalry.

🌊 Mary Anning (1799–1847) — The Finder

-

Role: Self-taught fossil collector on England’s Jurassic Coast

-

Key Discoveries:

-

First complete Ichthyosaurus

-

First scientifically accepted Plesiosaur

-

Early pterosaur (Dimorphodon)

-

-

Impact: Proved extinct reptiles once ruled the seas and skies

-

Obstacle: Working-class woman, largely uncredited in her lifetime

-

Legacy: “Mother of Paleontology”

🏛️ Richard Owen (1804–1892) — The Architect

-

Role: Anatomist and taxonomist; museum power broker

-

Key Contribution: Coined “Dinosauria” (1842)

-

Vision: Dinosaurs as massive, slow, reptilian giants

-

Institutions: British Museum (Natural History)

-

Controversy: Took credit from others (notably Gideon Mantell); opposed Darwin

-

Legacy: Created the conceptual framework of dinosaurs

🚂 Othniel Charles Marsh (1831–1899) — The General

-

Role: Yale professor; fossil empire builder

-

Key Discoveries:

-

Triceratops

-

Stegosaurus

-

Brontosaurus (with famous skull error)

-

-

Method: Large crews, railroads, explosives

-

Rivalry: Bitter feud with Cope (Bone Wars)

-

Legacy: Built America’s great dinosaur museums

⚡ Edward Drinker Cope (1840–1897) — The Prodigy

-

Role: Brilliant, fast, prolific paleontologist

-

Key Discoveries:

-

Coelophysis

-

Camarasaurus

-

Hundreds of new species

-

-

Mistake: Put the Elasmosaurus head on the wrong end

-

Theory: Cope’s Rule (lineages tend to grow larger over time)

-

Legacy: Scientific volume unmatched—over 1,000 species described

🧭 Two Great Conflicts

-

🇬🇧 Britain: Class & Credit (Anning vs. Owen)

-

🇺🇸 America: Speed & Spite (Marsh vs. Cope)

🦖 Evolution of the Dinosaur Idea

-

🌊 Sea monsters (Anning)

-

🐘 Sluggish giants (Owen)

-

🏃 Active, diverse animals (Marsh & Cope)

🏆 Why They Matter

Together, they:

-

Proved extinction was real

-

Defined dinosaurs as a group

-

Discovered the most classic species

-

Turned fossils into public science

If you’d like, I can next:

-

📊 Rank their discoveries by scientific importance

-

🧠 Compare their personalities and methods

-

🏛️ Trace how museums shaped dinosaur fame

-

🦕 Focus only on dinosaurs vs marine reptiles

Class & Credit: Anning vs. Owen

The relationship between Mary Anning (the working-class fossil hunter) and Sir Richard Owen (the elite anatomist) is one of the starkest examples of the “class ceiling” in the history of science. While they worked with the same bones, their worlds were entirely separate, and the credit for discovery flowed only one way: upward.

1. The Class Divide

-

Mary Anning (The Producer): Born into poverty in Lyme Regis, Anning was a “Dissenter” (religious minority) and a woman, barring her from universities, the Geological Society, and the “Gentleman’s Clubs” of science. She dug the fossils from the cliffs with her own hands, risking her life amid landslides, to sell them for subsistence. To the establishment, she was a commercial supplier rather than a peer.

-

Richard Owen (The Consumer): A politically savvy establishment figure, Owen was the man who coined the word “Dinosaur.” He sat in London museums, purchasing the specimens Anning found. He had the education to describe them in academic journals—the “currency” of scientific credit—while Anning was excluded from writing them.

2. The Theft of Credit

The core conflict was that Anning found the specimens, but Owen put his name on them.

-

The Plesiosaur Incident: When Anning discovered a pristine Plesiosaur skeleton, Owen described it in the scientific literature. In his papers, he rarely acknowledged her by name, often referring to her merely as a “collector” or omitting her entirely to maintain the illusion that the discovery was an institutional triumph rather than the work of a poor woman in Dorset.

-

The “Science” vs. “Labor” Distinction: Owen and his peers viewed excavation as “manual labor” and description as “intellectual labor.” They believed the credit belonged to the mind that classified the bone, not the hand that found it. Anning famously resented this, writing in a letter: “The world has used me so unkindly… I fear it has made me suspicious of everyone.”

3. The Legacy Shift

-

Then: Owen died a celebrity, knighted and famous as the “British Cuvier.” Anning died poor, with her only official recognition being an obituary in a geological journal (a rare honor for a woman, but a small one).

-

Now: History has reversed the credit. Owen is often remembered today as the villain of Victorian science (also for his feuds with Darwin and Gideon Mantell). At the same time, Mary Anning is celebrated as the true unsung heroine of paleontology, correctly identified as the discoverer of the Ichthyosaur and Plesiosaur.

“Bone Wars”, Cope vs. Marsh

The Bone Wars (also known as the “Great Dinosaur Rush”) was a period of intense and ruthless fossil speculation in the American West during the Gilded Age (approx. 1877–1892). It was defined by the bitter rivalry between Edward Drinker Cope (Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia) and Othniel Charles Marsh (Peabody Museum, Yale).

What started as a friendship turned into a scientific feud that involved bribery, theft, spying, and the destruction of bones.

The Tale of the Tape

| Feature | Edward Drinker Cope (The “Gunslinger”) | Othniel Charles Marsh (The “General”) |

| Base | Philadelphia, PA | New Haven, CT (Yale) |

| Personality | Erratic, brilliant, hot-tempered. | Cold, calculating, political. |

| Funding | Private (Family fortune, which he drained). | Institutional (Uncle George Peabody + US Govt). |

| Method | Speed: Published papers instantly. | Power: Used government influence to block rivals. |

| Key Find | Camarasaurus, Coelophysis. | Triceratops, Stegosaurus, Apatosaurus. |

1. The Spark: The Head on the Tail (1868)

The rivalry began with an embarrassing anatomical mistake.

- The Error: Cope reconstructed Elasmosaurus (a long-necked marine reptile) with its head at the tip of its tail.

- The Insult: Marsh publicly pointed out the error, humiliating Cope. Cope attempted to repurchase every copy of the journal to conceal his mistake, but Marsh retained his copy as leverage.

- The Result: A lifelong hatred was born.

2. The Tactics: Science as War

Once the “rush” moved to the dinosaur-rich beds of Wyoming, Colorado, and Nebraska, the gloves came off.

- Bribery & Poaching: Both men constantly tried to hire away the other’s field crews. If a farmer found a bone, Marsh would offer $10, and Cope would counter with $20.

- Spying: Marsh had employees infiltrate Cope’s dig sites to report on what he was finding.

- The “Telegraph” Papers: To establish “priority” (naming rights), Cope would send telegraphed descriptions of new species from the field for immediate publication, often resulting in errors and duplicate names.

- Dynamite: Perhaps the darkest tactic. When one team finished digging in a quarry, they sometimes detonated explosives or crushed the remaining bones to prevent the rival team from finding anything left behind.

3. The Climax: The “Media Bomb” (1890)

After years of Marsh using his position as head of the US Geological Survey (USGS) to cut off Cope’s funding, Cope retaliated.

- The Article: Cope handed a lifetime of notes and dirt to a journalist. The New York Herald ran a scandalous headline story accusing Marsh of plagiarism, incompetence, and misuse of government funds.

- The Fallout: Congress investigated the U.S. Geological Survey. While Marsh wasn’t criminally charged, his budget was slashed, and he was forced to fire most of his staff.

4. The Winner?

Both men effectively destroyed themselves.

- Cope died broke in a rented house, surrounded by bones he couldn’t afford to keep.

- Marsh died with $186 in his bank account, having spent his entire fortune on the war.

- The Real Winner: Science. Despite the chaos, the two men discovered more than 130 new dinosaur species. They filled America’s museums and sparked the global public fascination with dinosaurs that continues today.

Mary Anning

Anning with her dog, Tray, painted before 1842; the hill Golden Cap is visible in the background.

(Wiki Image Credited to ‘Mr. Grey’ in Crispin Tickell’s book ‘Mary Anning of Lyme Regis’ (1996) – Two versions side by side, Sedgwick Museum. Also see here. According to the Sedgwick Museum, there are two versions. The earlier version is by an unknown artist, dated before 1842, and is preserved in the Natural History Museum, London. The later version is a copy by B.J. M. Donne in 1847 or 1850, and is credited to the Geological Society, London. Also see here., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3824696)

Mary Anning Quotes

Because Mary Anning was a working-class woman in the early 19th century, she was barred from publishing scientific papers. Consequently, we don’t have volumes of her writing. However, her voice survives in letters, and the impressions she made on the wealthy geologists who visited her are well documented.

Here are the most significant quotes by her and about her.

I. In Her Own Words

Her quotes often reflect a mix of scientific confidence and bitterness at how the establishment treated her.

“The world has used me so unkindly, I fear it has made me suspicious of everyone.” — From a letter to a friend late in her life. (Context: This is her most famous and heartbreaking quote. After decades of finding fossils that built the careers of wealthy men who rarely credited her, she became disillusioned and cynical about the scientific community.)

“I am well known throughout the whole of Europe.” — Reported from a conversation with a tourist. (Context: Despite being ignored by the Geological Society in London, Anning was aware that her reputation had spread to the erratic geniuses of the continent. She knew her own worth, even if her countrymen tried to diminish it.)

“I beg your pardon, there are no such things as fancy stones. They are all organized substances—petrified bones of animals that existed before the Flood.” — Her correction to a customer. (Context: When tourists called her fossils “curiosities” or “fancy stones,” she would correct them with scientific precision. She saw herself as a scientist, not a souvenir seller.)

II. Quotes About Her (Contemporary)

Visitors were often shocked that a “poor, ignorant girl” knew more about anatomy than the professors.

“It is surely a wonderful instance of divine favour – that this poor, ignorant girl should be so blessed, for by reading and application she has arrived to that degree of knowledge as to be in the habit of writing and talking with professors and other clever men on the subject, and they all acknowledge that she understands more of the science than anyone else in this kingdom.” — Lady Harriet Silvester (1824), from her diary. (Context: This is the most defining account of Anning’s life. It highlights the class prejudice of the time—attributing her intelligence to “divine favour”—while admitting she knew more than the experts.)

“The carpenter’s daughter has won a name for herself, and has deserved to win it.” — Charles Dickens (1865). (Context: Dickens wrote a tribute article titled “Mary Anning, the Fossil Finder” in his magazine ‘All the Year Round’ after she died, helping to immortalize her story for the Victorian public.)

“Miss Anning… a prim, little, pedantic, vinegar-looking, thin female, shrewd, and rather satirical in her conversation.” — Gideon Mantell (Discoverer of the Iguanodon). (Context: Mantell, who was also an outsider to the elite London circle, visited her in 1832. His description captures her hardened, no-nonsense exterior developed after years of dangerous cliff work.)

III. The Tongue Twister

While not a direct quote, Mary Anning is widely believed to be the inspiration for the famous tongue twister written by Terry Sullivan in 1908:

“She sells sea-shells on the sea-shore, The shells she sells are sea-shells, I’m sure For if she sells sea-shells on the sea-shore Then I’m sure she sells sea-shore shells.”

(Note: While Mary sold fossils (“bones”) rather than seashells, the rhyme has become permanently linked to her legacy in Lyme Regis.)

IV. The Epitaph

When she died, the Geological Society of London—which had barred her from membership—paid for a stained-glass window in her local church. The inscription reads:

“This window is sacred to the memory of Mary Anning… who died March 9, 1847, and is erected by the Vicar and some members of the Geological Society of London in commemoration of her usefulness in furthering the science of geology, as also of her benevolence of heart and integrity of life.”

Mary Anning Chronological Table

The following chronological table outlines the life of Mary Anning, from a survivor of a lightning strike to the “Princess of Paleontology” whose discoveries fueled the careers of men like Richard Owen.

The Life & Discoveries of Mary Anning

| Year | Event | Details & Significance |

| 1799 | Birth | Born May 21 in Lyme Regis, Dorset, to a poor cabinetmaker and amateur fossil collector. |

| 1800 | The Lightning Strike | At 15 months old, she survives a lightning strike that kills her nurse and two other women. Local legend claims this event changed her from a sickly child into a bright, energetic one. |

| 1810 | Father’s Death | Her father, Richard Anning, dies of tuberculosis and injuries from a cliff fall, leaving the family £120 in debt. Mary and her brother Joseph begin selling “curiosities” (fossils) to tourists to survive. |

| 1811 | First Ichthyosaur Skull | Her brother Joseph finds a massive 4-foot skull in the cliffs. |

| 1812 | First Ichthyosaur Skeleton | Aged 12, Mary excavates the rest of the skeleton. It is the first correctly identified Ichthyosaur (“Fish Lizard”). It is sold for £23. |

| 1823 | First Plesiosaur | Mary discovers the first complete Plesiosaurus skeleton. The anatomy (long neck, tiny head) is so bizarre that French anatomist Georges Cuvier initially calls it a fake, until Mary provides proof. |

| 1826 | The Fossil Depot | She saves enough money to buy a glass-fronted shop, “Anning’s Fossil Depot,” in Lyme Regis. It becomes a destination for scientists and royalty. |

| 1828 | First British Pterosaur | She discovers Dimorphodon (a flying reptile), the first pterosaur skeleton ever found outside of Germany. |

| 1829 | Squaloraja Discovery | She discovers a transitional fossil linking sharks and rays (Squaloraja). |

| 1830 | Plesiosaur #2 | She discovers the most complete Plesiosaurus yet (sold for 200 guineas). This specimen becomes the model for the “Duria Antiquior” (the first scene of prehistoric life ever painted). |

| 1835 | Financial Crisis | She loses her life savings (~£300) in a nasty investment scam. |

| 1838 | Government Annuity | The British Association for the Advancement of Science and the Geological Society grant her an annuity (pension) of £25 per year, acknowledging her contribution to science. |

| 1839 | Owen Correspondence | Richard Owen visits Lyme Regis to examine her specimens. (He relies on her findings for his “Dinosauria” classification but rarely credits her in print). |

| 1844 | Royal Visit | King Frederick Augustus II of Saxony visits her shop. He buys an Ichthyosaur skeleton for his personal collection. |

| 1847 | Death | Mary died of breast cancer on March 9 at age 47. The Geological Society publishes a eulogy for her—an unprecedented honor for a woman at the time. |

| 2010 | Royal Society List | The Royal Society names her one of the ten British women who have most influenced the history of science. |

Mary Anning History

The geologist Henry De la Beche painted the influential watercolour Duria Antiquior in 1830, based mainly on fossils found by Mary Anning.

(Wiki Image By Henry De la Beche (10 February 1796 – 13 April 1855) – http://www.sedgwickmuseum.org/education/ideas_and_evidence.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2445061)

The history of Mary Anning is one of the most compelling stories in science—a tale of a working-class woman who, despite having no formal education and being barred from the scientific establishment, became the “Princess of Paleontology.”

1. The “Lightning Girl” of Lyme Regis

Mary Anning was born in 1799 in Lyme Regis, a coastal town in Dorset, England. Her life began with a near-supernatural event that local legend says defined her personality.

- The Incident (1800): At 15 months of age, she was being held by a neighbor beneath an elm tree during a storm. Lightning struck the tree, killing the neighbor and two other women. Mary was the only survivor. Her family claimed she changed from a sickly child into a bright, energetic “spark” after the event.

- The Family Business: Her father was a cabinetmaker who supplemented his income by selling “curiosities” (fossils) to tourists. When he died in 1810, he left the family £120 in debt. Mary, aged 11, climbed the dangerous cliffs to continue her work, not as a hobby but to feed her family.

2. The Discoveries: “Monsters” in the Mud

Between 1811 and 1830, Mary Anning discovered the key evidence that would prove the concept of extinction.

- The Ichthyosaur (1811-1812): Her brother found the skull, but 12-year-old Mary excavated the rest of the 17-foot skeleton. It was the first correctly identified Ichthyosaur.

- The Plesiosaur (1823): This was her most famous find. Its anatomy—a tiny head on a comically long neck—was so bizarre that the famous French anatomist Georges Cuvier accused her of faking it. She proved him wrong by finding a second one.

- The Flying Dragon (1828): She found the first British Dimorphodon (Pterosaur), proving that reptiles had once ruled the air as well as the sea.

3. The Scientist (Not Just a Collector)

History often remembers her as a simple “finder,” but she was a sharp scientific mind who corrected the professors who bought her stones.

- Coprolites: Scientists used to find strange “bezoar stones” in the cliffs. Mary was the one who cut them open, found fish scales inside, and correctly identified them as fossilized feces. This allowed scientists to reconstruct the food chain of the Jurassic seas.

- Ink Sacs: She discovered that fossilized belemnites (ancient squid-like creatures) still contained dried ink. She even gave some to a friend who reconstituted it and used the 200-million-year-old ink to draw a picture of the fossil!

4. The “Paper Ceiling.”

Despite her brilliance, Mary faced two insurmountable barriers: her gender and her class.

- The “Middlemen”: Male geologists (such as William Conybeare) would purchase her fossils, write scientific papers describing them, and build their careers on her work. They rarely credited her in the papers, often referring to her simply as the “proprietor.”

- The Exclusion: She was not allowed to join the Geological Society of London. She couldn’t even enter the building to hear the papers being read about her own discoveries.

5. Friendship and “Duria Antiquior.”

She did have allies. Her closest friend was the geologist Henry De la Beche. In 1830, when Mary was facing financial ruin, De la Beche painted “Duria Antiquior” (A More Ancient Dorset).

- This was the first painting in history to depict prehistoric life as a living, breathing ecosystem (depicting plesiosaurs eating pterosaurs, among other interactions).

- He printed it and sold copies to his wealthy friends, giving all the proceeds to Mary to keep her afloat.

6. Death and Recognition

Mary Anning died of breast cancer in 1847 at the age of 47.

- The Tray Tragedy: Years earlier, her faithful dog, Tray, who accompanied her on every dig, was killed in a landslide that occurred just inches from Mary. She was heartbroken and marked the decline of her own spirit from that day.

- The Eulogy: Upon her death, the Geological Society did something unprecedented: they published a eulogy for her, the first time they had ever honored a woman. Today, the “Sea Dragons” she found still hang on the walls of the Natural History Museum in London.

Mary Anning’s 8 Top Paleontology Contributions

Here are the Top 8 Paleontological Contributions of Mary Anning. These are the specific discoveries and scientific breakthroughs that transformed her from a poor village girl into the most important fossil hunter of the 19th century.

- The First Complete Ichthyosaur (1811)

- The Find: At age 12, shortly after her father’s death, Mary excavated a 17-foot skeleton that her brother Joseph had spotted.

- The Impact: Previously, people found scattered bones and assumed they were those of crocodiles or biblical victims of Noah’s Flood. Mary’s specimen proved this was a completely new, unknown animal—a “Fish Lizard” adapted for the open ocean.

- The First Complete Plesiosaur (1823)

- The Find: She discovered the Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus. It had a tiny head, a snake-like neck, and a turtle-like body.

- The Controversy: It seemed impossible, so Georges Cuvier (the father of anatomy) declared it a fake, suggesting Mary had glued different bones together. Mary defended her work, a special meeting was held in London, and Cuvier was forced to admit he was wrong.

- The Legacy: This cemented her reputation as a serious anatomist, not just a collector.

- The First British Pterosaur (1828)

- The Find: She discovered the Dimorphodon macronyx.

- The Impact: Until this moment, flying reptiles (Pterodactyls) had only been found in Solnhofen, Germany. Mary’s discovery proved that these “flying dragons” were not a local fluke but a widespread dominant group. It was the first time the British public realized the sky, like the sea, had been ruled by reptiles.

- Solving the “Bezoar Stone” Mystery (Coprolites)

- The Science: For years, scientists found strange, spiral-shaped stones inside the ribcages of skeletons. They called them “Bezoar stones.”

- The Breakthrough: Mary cut them open and found digested fish scales and bone fragments inside. She correctly identified them as fossilized feces.

- The Impact: This gave rise to the field of Paleoecology. It allowed scientists not only to observe the animals but also to understand what they ate and how they lived.

- The “Ink” of the Belemnite

- The Find: Belemnites were common cone-shaped fossils (ancient relatives of squids). Mary discovered that some specimens still contained their fossilized ink sacs.

- The Anecdote: She realized the ink was still viable. Her friend Elizabeth Philpot actually reconstituted the 200-million-year-old ink with water and used it to draw illustrations of the fossils—a direct connection to the Jurassic ocean.

- The Shark-Ray Link (Squaloraja) (1829)

- The Find: She found a strange, flattened fish that seemed to be half-shark and half-ray.

- The Impact: This was a transitional fossil (a “missing link”). It helped evolutionary scientists understand the lineage of modern cartilaginous fish, showing how rays evolved from shark-like ancestors.

- The “Great Sea Dragon” (Temnodontosaurus)

- The Find: While the first Ichthyosaur was impressive, Mary later found the massive Temnodontosaurus platyodon.

- The Impact: This monster had an eye the size of a dinner plate. It demonstrated that the Jurassic seas were home to apex predators of immense size, changing public perception of the ancient ocean from a “lagoon” to a dangerous, violent ecosystem.

- Proof of Extinction (The “Deep Time” Shift)

- The Philosophy: In the early 1800s, most people believed God would not allow any of his creations to die out completely. They assumed that strange bones belonged to animals still living in unexplored regions (such as Africa).

- The Impact: Mary’s discoveries were so significant and so unlike anything living today that they made that argument impossible. Her fossils forced the scientific community to accept Extinction as a fact, paving the way for Darwin’s theory of evolution.

How did Mary Anning learn to identify these bones without any formal education, or perhaps about her relationship with her friend Elizabeth Philpot?

Mary Anning, The First Complete Ichthyosaur (1811)

Drawing from an 1814 paper by Everard Home showing the skull of Temnodontosaurus platyodon (previously Ichthyosaurus platyodon) (NHMUK PV R 1158), found by Joseph Anning in 1811

(Wiki Image By Everard Home (1756 – 1832) – Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 1814, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8942612)

In 1811, a 12-year-old Mary Anning (and her brother Joseph) discovered the first scientifically identified Ichthyosaur skeleton. This discovery was the “big bang” for the field of marine paleontology because it proved that giant, unknown reptiles had once ruled the seas, challenging the biblical view of creation.

The Discovery (1811–1812)

- The Skull (Joseph’s Find): In 1811, Mary’s brother, Joseph Anning, saw a massive 4-foot skull sticking out of the cliffs near Lyme Regis (specifically the Black Ven/Church Cliffs area). It looked like a crocodile, but the eyes were far too large.

- The Skeleton (Mary’s Find): About a year later, in 1812, 12-year-old Mary Anning returned to the spot after a storm had eroded the cliff face. She carefully excavated the rest of the 17-foot skeleton—vertebrae, ribs, and paddles.

- The Price: The family sold it for £23 (approximately £2,000 in today’s terms) to a local collector, who later sold it to the British Museum.

The Science: “The Fish Lizard”

At the time, scientists called it a “mystery.” They couldn’t decide if it was a crocodile or a fish.

- The Name: It was eventually named Ichthyosaurus (“Fish Lizard”).

- The Species: We now know this specific specimen was a Temnodontosaurus platyodon (“Cutting-tooth lizard”), a massive apex predator that grew up to 30 feet long.

- The Impact: This fossil was the first clear evidence against the religious doctrine that God’s creation was perfect and unchanging. If this giant “sea dragon” no longer existed, it meant extinction was real.

Where is it now?

- The Skull: The original skull found by Joseph is still on display at the Natural History Museum in London (Specimen number NHMUK PV R1158).

- The Body: Sadly, the rest of the skeleton (the vertebrae and ribs Mary found) was lost sometime during the 19th century, likely discarded or misplaced as collections were moved between museums. Only the skull remains of the original find.

Mary Anning, The First Complete Plesiosaur (1823)

In December 1823, Mary Anning made the discovery that turned her from a local curiosity into a scientific legend: the first complete Plesiosaur.

While the Ichthyosaur was strange, it at least looked somewhat like a fish or a crocodile. The Plesiosaur was unlike anything scientists had ever seen, leading to one of the biggest controversies in early paleontology.

The Discovery

- Date: December 10, 1823.

- Location: Black Ven, near Lyme Regis.

- The Specimen: A nearly perfect 9-foot skeleton. While scattered vertebrae had been found before, this was the first time the head, neck, and body were found connected.

- The Anatomy: It had a tiny skull (only about 4-5 inches long), a ridiculously long neck (almost half the animal’s length), a broad barrel-shaped body, and four large paddles.

- The Quote: The geologist William Buckland later described it as resembling “a snake threaded through the shell of a turtle.”

The Controversy: “It’s a Fake”

When sketches of the skeleton were sent to London and Paris, the scientific elite were skeptical.

- The Accusation: Georges Cuvier, the most famous anatomist in the world (known as the “Napoleon of Intelligence”), declared it a fraud. He argued that no animal could physically exist with a neck that long (35 vertebrae) without breaking. He suggested Mary had glued the neck of a snake to the body of a lizard.

- The Vindication: In 1824, a special meeting of the Geological Society of London was held to debate the fossil. Mary Anning was not invited (women were banned). However, her friend, the geologist William Conybeare, presented the physical rock slab.

- The Verdict: Upon seeing the actual stone, Cuvier admitted he was wrong, famously stating, “She has found the most remarkable animal of the whole of creation.”

The Scientific Name

- Name: Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus (“Near Lizard with a long neck”).

- Significance: This discovery confirmed that ancient seas were home to a diverse ecosystem of reptiles, not a single type. It became the centerpiece of the “Age of Reptiles” theory.

Where is it now?

Like her first Ichthyosaur, this specimen was sold to a wealthy collector (the Duke of Buckingham) for approximately £100-£150. Today, the original Holotype (the specimen used to define the species) resides at the Natural History Museum in London (Specimen number NHMUK PV R1313), where it remains one of the museum’s most prized possessions.

Here is the picture of the first complete Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus skeleton discovered by Mary Anning in 1823:

This image shows the original, nearly 9-foot-long specimen, often referred to as the Holotype (NHMUK PV R1313) and housed at the Natural History Museum in London. It perfectly illustrates the animal’s highly controversial anatomy: a small head, a broad turtle-like body, and an impossibly long neck composed of 35 vertebrae.

Mary Anning, The First British Pterosaur (1828)

Mary Anning, the pioneering fossil collector from Lyme Regis, made the momentous discovery of the first Pterosaur fossil found in Britain (and only the second in the world) in 1828.

This discovery was one of her most important, following her earlier finds of the Ichthyosaur and Plesiosaur.

The Discovery and its Name

- Location: The Jurassic cliffs near her home in Lyme Regis, on England’s famous Jurassic Coast.

- The Find: The fossil consisted of a partial skeleton, including the skull and wing bones, of a flying reptile.

- Initial Name: The fossil was originally named Pterodactylus macronyx by the geologist William Buckland in 1829.

- Modern Name: The fossil was later reclassified and is now known as Dimorphodon macronyx, meaning “two-form tooth,” referring to the two distinct types of teeth in its jaw—a feature that distinguished it from its German counterpart.

Significance of the Pterosaur

The discovery was sensational because it proved, once again, the existence of extraordinary creatures that had no modern equivalent:

- Flying Reptiles: Along with the earlier German find, Anning’s Pterosaur confirmed that the ancient world was home to flying reptiles.

- British Paleontology: It cemented Britain’s position as a center of discovery of these prehistoric “monsters” and helped drive the new science of paleontology.

As was common throughout her career, Anning was the one who risked her life on the unstable cliffs to find the fossil. Yet the formal recognition and naming of the species were the responsibility of the established (male) geologists who bought the specimen from her.

Here is the image of the fossil of the first Pterosaur (flying reptile) discovered in Britain, found by Mary Anning in 1828.

This specimen, originally named Pterodactylus macronyx and later reclassified as Dimorphodon macronyx, is significant for showcasing the unique anatomy of these flying reptiles, including the characteristic long bones of the wings (which are essentially elongated fourth fingers) and its specialized skull.

Mary Anning, Solving the “Bezoar Stone” Mystery (Coprolites)

Mary Anning played a critical role in solving the geological puzzle of the so-called “Bezoar Stones,” thereby advancing scientific understanding of coprolites (fossilized feces).

This achievement exemplifies how Anning’s keen observational skills, honed through decades of fieldwork, surpassed the theoretical knowledge of the era’s leading academic geologists.

The Mystery of the “Bezoar Stones”

For years, geologists were puzzled by the common, dark, rounded stones found embedded in the Jurassic cliffs of Lyme Regis. They were known locally as “bezoar stones” (a term often used for medicinal masses found in animal stomachs) or “fossil balls.” Their origins and composition were unknown.

Anning’s Observation

Mary Anning solved the mystery through direct, practical observation:

- She noticed the Location: Anning began to notice these rounded stones within the abdominal and pelvic cavities of complete Ichthyosaur skeletons she excavated.

- She noticed the Contents: She carefully broke open the stones and found they contained fossilized fish scales, bone fragments, and other undigested matter.

- The Conclusion: She deduced that these stones were the fossilized excrement of the creatures she was excavating. Her simple, irrefutable evidence was the key to understanding them.

Scientific Significance

Anning brought her observations and specimens to William Buckland, a highly respected geologist at Oxford University. Buckland was initially skeptical but was convinced by the evidence found inside the stones and their placement within the skeletons Anning had prepared.

- Formal Naming: In 1829, Buckland formally described and named these fossils “coprolites” (from the Greek kopros [dung] and lithos [stone]).

- Legacy: Anning’s discovery launched a new field of paleontological study, enabling scientists to analyze ancient diets, digestive systems, and ecosystems from fossilized waste.

This observation is considered a significant contribution to paleoecology.

Here is a picture of a coprolite (fossilized feces), illustrating the kind of specimen Mary Anning used to solve the mystery of the “Bezoar Stones.”

The image shows a cross-section of a coprolite, often revealing its dark, rounded shape and embedded contents—such as fish scales or bone fragments—that supported Anning’s observation that these stones were the fossilized digestive waste of ancient reptiles like the Ichthyosaur. This discovery was critical to the early study of paleoecology.

Mary Anning, The “Ink” of the Belemnite

This is one of the most poetic and tangible discoveries in Mary Anning’s career. It wasn’t a giant monster, but a minor biological miracle that allowed 19th-century artists to paint with the past literally.

While excavating the common Belemnite fossils (ancient squid relatives), Mary discovered that their ink sacs had been fossilized so perfectly that the ink could still be used.

The Fossil: The “Thunderbolt”

- The Creature: Belemnites were cephalopods, similar to modern squid and cuttlefish, that lived in Jurassic seas. They had a soft body and a hard, bullet-shaped internal shell.

- Folklore: For centuries, locals found these bullet-shaped shells on the beach and called them “Thunderbolts,” believing they fell from the sky during storms.

- Mary’s Insight: Mary understood they were internal shells of sea creatures. She began finding specimens that still had the “phragmocone” (chambered shell) attached, and crucially, a dark, black stain inside.

The Discovery: Fossilized Melanin

Sometime in the late 1820s, Mary realized that the black substance inside the fossil wasn’t just rock—it was the animal’s ink sac, preserved for 200 million years.

- The Comparison: She dissected modern squid and cuttlefish to compare their anatomy with that of fossils, demonstrating that the ancient Belemnite had an identical defense mechanism: squirting ink to confuse predators.

- The Preservation: The fact that the ink survived indicates the animal must have been buried instantly in soft mud (in anoxic conditions) to prevent decay.

The “Magic” Trick: Reviving the Ink

This discovery led to a famous collaboration with her close friend and fellow fossil hunter, Elizabeth Philpot.

- The Experiment: They scraped the dried, 200-million-year-old fossilized ink out of the sac.

- The Result: When they ground it into a powder and mixed it with water, it reconstituted into a viable, dark brown pigment (similar to Sepia).

- The Art: Elizabeth Philpot used this “fossil ink” to paint scientific illustrations of the very Ichthyosaurs and Belemnites Mary was finding. She drew the creature using its own ink.

The Impact

This was a major breakthrough for Taphonomy (the study of how fossils decay and preserve).

- Soft Tissue: It proved that under the right conditions, soft tissues (like ink sacs), not just hard bones, could fossilize.

- Behavior: It showed that these ancient creatures had the same predator-avoidance behaviors as modern squid, linking the Jurassic world directly to the modern one.

Fun Fact: The famous geologist William Buckland was so amused by this that he famously drew a picture of a stylized Jurassic scene using Mary Anning’s fossil ink.

Here is a picture showing the remarkable discovery of the Belemnite’s fossilized ink, often accompanied by drawings made using the ancient pigment itself.

This image often features the preserved, black ink sac alongside a drawing (such as a sketch of an Ichthyosaur or a Belemnite) created by grinding the 200-million-year-old fossilized melanin and reconstituting it into usable sepia-toned ink, a testament to Mary Anning’s acute observational skill.

Mary Anning, The Shark-Ray Link (Squaloraja) (1829)

In 1829, while the scientific world was still reeling from her discovery of the Pterosaur, Mary Anning found yet another “impossible” animal in the Blue Lias cliffs. This time, it wasn’t a reptile but a fish that appeared to be a hybrid of two different families.

She discovered Squaloraja, a “missing link” that bridged the gap between sharks and rays.

The Discovery

- Date: December 1829.

- Location: Lyme Regis.

- The Specimen: A flattened, cartilaginous fish. Unlike bony fish, cartilaginous skeletons (like those of sharks) rarely fossilize because they are soft and decay quickly. Finding one this well-preserved was a miracle of taphonomy.

- The Name: The name literally translates to “Shark-Ray” (Squalus = Shark, Raja = Ray). The specific species is Squaloraja polyspondyla.

The “Chimera” Anatomy

Scientists at the time were perplexed because the animal had features that were mutually exclusive.

- The Ray Part: It had a broad, flattened body and large pectoral fins, suggesting that it lived on the sea floor, as in modern skates and rays.

- The Shark Part: It had a long, thick tail without the “stinging” spine of a stingray, and its skin was covered in “dermal denticles” (prickly scales) characteristic of sharks.

- The “Nose”: It featured a long, bony snout (rostrum) resembling a sawfish, but without the lateral teeth.

The Evolutionary Significance

This was one of the earliest examples of a Transitional Fossil.

- The Split: Evolutionarily, sharks and rays share a common ancestor. Squaloraja sits right at the point where these two groups diverged.

- The Proof: It proved that rays are essentially “flattened sharks.” It showed the gradual adaptation of shark-like ancestors as they moved to the seabed and evolved flattened bodies to hunt in the sand.

The Human Element

This discovery highlights Mary Anning’s incredible eye for detail. To the untrained eye, a flattened cartilaginous fish looks like a smudge of mud on a rock. Mary recognized the subtle texture of the skin (the denticles) and the faint outline of the cartilage, carefully extracting a specimen that the tide would have otherwise destroyed.

Where is it now? The holotype is held in the Natural History Museum in London (Specimen NHMUK PV P42). It is considered one of the most critical fossil fish in the world because it captures a specific moment of evolutionary divergence.

Here is the image of the rare cartilaginous fish fossil, Squaloraja polyspondyla, discovered by Mary Anning in 1829.

This fossil is highly significant because its flattened body and large fins are ray-like. In contrast, its dermal denticles (scales) and long tail are shark-like, leading to its recognition as an important transitional fossil that documents the divergence of sharks (Squalus) and rays (Raja). The preservation of its cartilage skeleton is exceptionally rare.

Mary Anning, The “Great Sea Dragon” (Temnodontosaurus)

While Mary Anning’s first discovery in 1811 was called an “Ichthyosaur” at the time, later classification revealed it to be something much more terrifying. It wasn’t just a dolphin-like reptile; it was a Temnodontosaurus (“Cutting-tooth Lizard”), the apex predator of the Early Jurassic ocean.

Here is the profile of the “Great Sea Dragon” that Mary Anning introduced to the world.

The Fossil: A 30-Foot Giant

Most people imagine Ichthyosaurs as 6-foot, dolphin-sized creatures. The Temnodontosaurus was a different beast entirely.

- Size: It grew up to 9–12 meters (30–40 feet) long.

- The Skull: The head alone was nearly 2 meters (6.5 feet) long.

- The Teeth: Unlike smaller ichthyosaurs that had needle-like teeth for catching fish, this one had thick, serrated cutting teeth. It didn’t just eat fish; it also ate other marine reptiles (such as smaller ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs).

The Anatomy: The Eye of the Deep

The most shocking feature Mary Anning revealed was the eye.

- Size: The Temnodontosaurus had the largest eyes of any animal in history, reaching up to 25 cm (10 inches) across—the size of a dinner plate.

- The Sclerotic Ring: Mary found bony plates inside the eye socket (sclerotic rings). These rings helped the eye retain its shape under the immense pressure of the deep ocean, proving that these animals were deep-sea hunters that relied on sight in the dark.

The Discovery Context

While the 1811/1812 skeleton (found by Joseph and Mary) was the first Temnodontosaurus, Mary continued to see massive fragments of this species throughout her life.

- The “T-Rex” of the Sea: Her discoveries proved that the Jurassic ocean wasn’t just filled with passive swimmers; it was a violent ecosystem with a distinct food chain, topped by this “Great Sea Dragon.”

Where is it now?

The massive skull that initiated the study (found by Joseph in 1811 and excavated by Mary) remains one of the most imposing exhibits at the Natural History Museum in London. You can see the terrifying row of teeth that gave the “Cutting-tooth Lizard” its name.

Here is an image of the fossil skull of the “Great Sea Dragon,” Temnodontosaurus, discovered by Mary Anning, which highlights its massive size and terrifying teeth.

This fossil is particularly known for:

- Size: Its skull alone could measure over six feet long, belonging to an animal up to 40 feet in length.

- Teeth: It possessed large, thick, serrated cutting teeth, which earned it the species name Temnodontosaurus (“Cutting-tooth Lizard”) and made it the apex predator of the Early Jurassic seas.

- The Eye: The image often reveals the massive orbital socket (for the eye), which housed the largest eyes ever known, allowing it to hunt in the deep, dark ocean.

Mary Anning, Proof of Extinction (The “Deep Time” Shift)

Mary Anning didn’t just find bones; she found the “smoking gun” that killed the idea of a young, unchanging Earth.

Before her discoveries in the early 19th century, the scientific and religious consensus was that extinction was impossible. Her fossils were the physical evidence that forced humanity to accept that we live on a planet with a history spanning millions of years (“Deep Time”), inhabited by eras of creatures that completely vanished.

- The Old Belief: “God Makes No Mistakes”

In the early 1800s, the prevailing view in Europe was based on a literal interpretation of the Bible (Genesis).

- The Fixity of Species: God created all animals perfect and complete. To suggest an entire species had died out implied that God’s creation was imperfect or that he had made a mistake.

- The “Hiding” Theory: When people found strange bones (like Mammoths), they explained them away by saying, “These animals aren’t dead; they are just hiding in the unexplored forests of America or Siberia.”

- The Anning Evidence: “Too Big to Hide”

Mary Anning’s discoveries made the “Hiding Theory” impossible to defend.

- No Modern Cousins: While a Mammoth looks like an elephant (so it was easy to think they were related), a Plesiosaur or Ichthyosaur looked like nothing alive on Earth.

- The Ocean Problem: You might hide a Mammoth in a forest, but you cannot hide a 30-foot marine reptile in the English Channel or the Atlantic without sailors seeing it.

- The Conclusion: If these giant monsters weren’t hiding, they must be dead. And not just dead—gone forever.

- The Scientific Shift: Cuvier & Catastrophism

Mary Anning provided the ammunition for Georges Cuvier, the famous French anatomist (the “Father of Paleontology”).

- The Partnership: Cuvier never visited Lyme Regis, but he studied drawings and descriptions of Anning’s finds (like the Plesiosaur).

- The Theory: He used her “sea dragons” to support his Catastrophism—the idea that the Earth had undergone violent, sudden changes (floods, ice ages) that wiped out entire ecosystems.

- The Impact: This legitimized the concept of Extinction as a scientific fact. It demonstrated that there was an “Age of Reptiles” preceding the “Age of Mammals.”

- The “Deep Time” Reality

Anning’s work helped extend Earth’s timescale from thousands to millions of years.

- The Blue Lias Cliffs: She worked on the “Jurassic Coast,” where layers of rock (strata) were clearly stacked like a cake.

- The Sequence: She found different fossils in different layers. This visual proof showed that Earth had distinct “chapters” of history. She wasn’t just finding random bones; she was reading the pages of a book that was millions of years old.

Summary

Mary Anning’s fossils were the psychological tipping point. They turned the concept of “Prehistoric” from a myth into a physical reality that you could touch, hold, and sell for £23.

The visual proof of Mary Anning’s contribution to the theory of Extinction and Deep Time is best represented by the fossils that were too large and too unique to be dismissed as living creatures hiding somewhere.

Here is an image illustrating the magnitude and strangeness of the fossils—specifically the Ichthyosaur and the Plesiosaur—that forced the world to accept the reality of prehistoric life and extinction:

This image often features a historical illustration or museum reconstruction of these marine reptiles, whose bizarre anatomies shattered the 19th-century scientific consensus on the fixity of species and the young age of the Earth. Anning’s spectacular finds provided the undeniable physical evidence that whole worlds of life existed and vanished long before humanity.

Mary Anning YouTube Links Views

The following collection of YouTube videos covers Mary Anning’s life, from animated biographies and short documentaries to songs.

Documentaries & Biographies

- Mary Anning – Princess of Paleontology – Extra History

- Views: 1,140,401

- Link: Watch Video

- Summary: A highly popular animated history of her life, covering her discoveries and the challenges she faced as a woman in science.

- Great Minds: Mary Anning, “The Greatest Fossilist in the World”

- Views: 332,757

- Link: Watch Video

- Summary: Hosted by Hank Green (SciShow), this is a quick, engaging overview of her major contributions.

- The true story of Mary Anning: The girl who helped discover dinosaurs | BBC Ideas

- Views: 146,685

- Link: Watch Video

- Summary: A concise look at how she changed scientific thinking worldwide without getting the credit she deserved.

- MARY ANNING | Omeleto

- Views: 125,929

- Link: Watch Video

- Summary: A short film dramatizing her struggle to make a scientific discovery.

For Kids & Education

- Mary Anning: Fossil Hunter | Science for Kids

- Views: 574,895

- Link: Watch Video

- Summary: A child-friendly introduction to her life as a fossil hunter.

- Fossil hunting with Mary Anning in the UK | PBS Eons

- Views: 63,447

- Link: Watch Video

- Summary: A recent feature from the popular PBS Eons channel explores her hunting grounds.

Songs

- Mary Anning | Children’s Song With Lyrics

- Views: 7,306

- Link: Watch Video

- Summary: An educational song for younger children to learn about their history.

- The Mary Anning Song (Elinor Wonders Why)

- Views: 8,245

- Link: Watch Video

- Summary: A clip from the animated show Elinor Wonders Why featuring a song about her.

Mary Anning Books

There is a surprising variety of books about Mary Anning, ranging from academic biographies to bestselling historical novels. Because she left behind so few letters, authors often use fiction to fill in the gaps of her personality.

Here are the best books on Mary Anning, categorized by genre and age group.

I. For Adults: Biography & Non-Fiction

If you want the facts, the science, and the history of the “Bone Wars” era.

- “The Fossil Hunter: Dinosaurs, Evolution, and the Woman Whose Discoveries Changed the World” by Shelley Emling

- Best For: The standard, all-around biography.

- The Gist: This is widely considered the definitive modern biography. Emling does an excellent job of situating Anning within the 19th-century scientific community. It details her struggle for recognition against the “gentleman geologists” and explores how her discoveries directly influenced the theories of Deep Time and Evolution (even before Darwin).

- “Jurassic Mary: Mary Anning and the Primeval Monsters” by Patricia Pierce

- Best For: A focus on the class and gender struggle.

- The Gist: This biography emphasizes the social barriers Anning faced. It paints a vivid picture of the poverty of Lyme Regis and the specific injustices of the Victorian class system that kept her from being acknowledged as a scientist.

II. For Adults: Historical Fiction

If you want a narrative story that brings her emotional life to existence.

- “Remarkable Creatures” by Tracy Chevalier

- Best For: A moving story of female friendship.

- The Gist: Written by the author of Girl with a Pearl Earring, this is the most famous novel about Anning. It focuses on the unlikely friendship between the working-class Mary and the wealthy spinster Elizabeth Philpot (who was a real person and a fossil hunter herself). It is excellent at depicting the tension between “The Finder” (Mary) and “The Establishment.”

- “Curiosity” by Joan Thomas

- Best For: A darker, grittier romance.

- The Gist: This novel takes more creative liberties, imagining a romance between Mary and the geologist Henry De la Beche. It is darker and more atmospheric than Remarkable Creatures, focusing on the harshness of her life and the predatory nature of the collectors who visited her.

III. For Young Adults & Middle Grade (Ages 10-14)

Bridge books for readers too old for picture books, but who want an engaging story.

- “Lightning Mary” by Anthea Simmons

- Best For: First-person adventure.

- The Gist: Told from Mary’s perspective, this book covers the year leading up to her discovery of the Ichthyosaur. It is gritty and fast-paced, effectively showing her prickly, stubborn personality and her “obsessive” nature in her pursuit of the monster on the cliffs.

- “Fossil Hunter: How Mary Anning Changed the Science of Prehistoric Life” by Cheryl Blackford

- Suitable for: Visual learning and science enthusiasts.

- The Gist: A beautifully designed non-fiction book that includes photos of the actual fossils, maps of the Jurassic Coast, and sidebars about the science of paleontology.

IV. For Children (Picture Books)

To introduce the “Princess of Paleontology” to the next generation.

- “Stone Girl, Bone Girl: The Story of Mary Anning” by Laurence Anholt

- Best For: The classic introduction (Ages 4-8).

- The Gist: Beautifully illustrated, this story follows the “Lightning Girl” and her dog, Tray. It captures the magic of discovery and is very inspiring for young girls interested in science.

- “Mary Anning’s Curiosity” by Monica Kulling

- Best For: Early chapter book readers (Ages 7-9).

- The Gist: A gentle introduction to her life that focuses on the excitement of the hunt and the bond with her family.

- “Little People, BIG DREAMS: Mary Anning”

- Best For: Toddlers and very young readers.

- The Gist: Part of the famous biography series, this simplifies her life into a clear message: she was curious, she worked hard, and she changed the world.

Quick Recommendation Guide

- If you read one book, go with “Remarkable Creatures” (Fiction) or “The Fossil Hunter” (Non-Fiction).

- If you are buying for a 12-year-old, “Lightning Mary.”

- If you are buying for a 6-year-old, “Stone Girl, Bone Girl.”

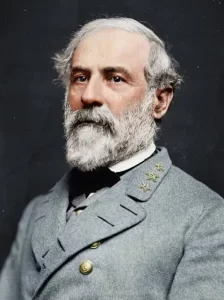

Richard Owen

Portrait of Owen, c. 1878

(Wiki Image By Lock & Whitfield – https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/use-this-image/?mkey=mw123958, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=109315079)

Richard Owen Quotes

Richard Owen’s words reflect his formal, often arrogant, and deeply academic nature. Unlike the scrappy, underdog voice of Mary Anning, Owen spoke with the weight of the “Establishment.”

Here are the most defining quotes by him and the rather brutal quotes about him from his rivals.

I. In His Own Words

- Coining the Name (1842). This is the sentence that changed paleontology. In his report to the British Association, he unified the scattered giants into one ruling dynasty.

“The combination of such characters altogether peculiar among Reptiles… and all manifested by creatures far surpassing in size the largest of existing reptiles, will, it is presumed, be deemed sufficient ground for establishing a distinct tribe or sub-order of Saurian Reptiles, for which I would propose the name of Dinosauria.”

- The Divine Archetype Owen was a creationist who believed evolution was not random, but followed a divine blueprint. This quote defines his philosophy of the “Archetype” (the perfect pattern in God’s mind).

“That ideal original or fundamental pattern on which a natural group of animals or system of organs has been constructed, and to modifications of which the various forms of such animals or organs may be referred.”

- The Satisfaction of “The Moa” After predicting the existence of a 12-foot bird from a single six-inch bone fragment (and being mocked for it), Owen wrote this when the full skeleton arrived, proving him right.

“So far as my skill in interpreting an osseous fragment may be credited, I am willing to risk my reputation for it on this statement.”

- On the “Homology” of Humans and Apes, Owen often struggled to balance his religious belief that humans were special with the anatomical reality that we are just primates.

“I cannot shut my eyes to the significance of the all-pervading similitude of structure—every tooth, every bone, strictly homologous—which makes the determination of the difference between Homo and Pithecus the anatomist’s difficulty.”

II. Quotes About Him (The Rivalry)

Richard Owen was widely respected for his intellect but universally disliked for his personality. His rivals—Charles Darwin and Thomas Huxley—did not hold back in their private letters.

- Charles Darwin (The “Frenemy”) Darwin and Owen started as friends but became bitter enemies after Owen wrote anonymous articles attacking the Origin of Species.

“The Londoners say he is mad with envy because my book is so talked about. It is painful to be hated in the intense degree with which Owen hates me.”

“He is spiteful, extremely malignant, and clever.”

“By Jove, I believe he thinks a sort of Bear was the grandpapa of Whales!” (Darwin mocking Owen’s criticism of his theory on whale evolution).

- Thomas Huxley (“Darwin’s Bulldog”) despised Owen for using his authority to block younger scientists. When Huxley proved Owen wrong about the anatomy of the ape brain (The Great Hippocampus Question), he wrote this to a friend:

“I will nail him out, like a kite to a barn door, an example to all evil doers.”

“[He is] a man of ambiguous phrases and twisted sentences.”

- Gideon Mantell (the victim) believed that Owen had stolen his research and ruined his life.

“Owen is a man of great power, but of no heart… he is an intellectual giant, but a moral dwarf.”

III. The Epitaph

Despite the feuds, Owen’s contribution to science was undeniable. His memorial in the Natural History Museum (which he built) acknowledges his dual nature as a brilliant organizer but a difficult man.

“The greatest anatomist of his age… He loved Nature and Art, and he built this Museum to be their home.”

Richard Owen: The Man Who Invented The Dinosaur

This video provides an excellent summary of his life, balancing his brilliant scientific achievements with his notoriously difficult personality and his feuds with Darwin.

Richard Owen Chronological Table

Here is the chronology of Sir Richard Owen, the man who named the dinosaurs and built the Natural History Museum, tracing his rise to power and his eventual fall during the Darwinian revolution.

The Life of Richard Owen: The Architect of Nature

| Year | Event | Significance |

| 1804 | Birth | Born in Lancaster, England. He initially trains to be a surgeon but discovers his true talent is in anatomy. |

| 1827 | The Hunterian Collection | He became the Assistant Conservator at the Royal College of Surgeons. His job is to organize the chaotic collection of John Hunter, which trains him to see the “hidden patterns” in bones. |

| 1837 | Darwin’s “Lost Giants” | A young Charles Darwin returns from the HMS Beagle with strange South American fossils. Owen identifies them as Toxodon and Glyptodon, proving the “Law of Succession.” |

| 1839 | The Moa Prediction | The Sherlock Holmes Moment. Based on a single 6-inch bone fragment, Owen predicts the existence of a giant, flightless bird in New Zealand. Four years later, the full skeleton proves him right. |

| 1842 | “Dinosauria” Coined | The Defining Moment. In a report to the British Association, Owen groups Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus together. He coined the name Dinosauria (“Fearfully Great Lizards”). |

| 1843 | Homology Defined | He presents his definition of Homology (same organ, different function) versus analogy (different organ, same function). This becomes the standard language of biology. |

| 1845 | Mammal-Like Reptiles | He describes Dicynodon from South Africa, identifying it as a Synapsid—the reptile that eventually evolved into mammals. |

| 1849 | “Nature of Limbs” | He publishes his theory of the Vertebrate Archetype—the idea that all animals are variations of a single divine blueprint. |

| 1854 | Crystal Palace Dinosaurs | He oversees the creation of the first life-sized dinosaur statues in London. He depicts them as heavy, rhinoceros-like quadrupeds to demonstrate that they were “superior” reptiles. |

| 1856 | Museum Superintendent | He oversees the Natural History Department at the British Museum. He immediately begins lobbying for a separate building, arguing that nature deserves a “Cathedral.” |

| 1859 | The Origin of Species | Charles Darwin publishes his theory. Owen, jealous and religiously opposed, writes anonymous, biting reviews attacking the book. The friendship ends. |

| 1860 | The Great Hippocampus Question | Owen claims that human brains have a structure (the hippocampus minor) that ape brains lack. Thomas Huxley publicly proved him wrong, damaging Owen’s reputation. |

| 1863 | The “London Specimen” | Owen secures the Archaeopteryx for the British Museum. He describes it as a bird, missing the evolutionary link to dinosaurs that Huxley later points out. |

| 1881 | The Museum Opens | His Magnum Opus. The Natural History Museum in South Kensington opens its doors. It is free to the public and arranged according to Owen’s classification system. |

| 1884 | Knighthood | He has been created a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB), becoming Sir Richard Owen. |

| 1892 | Death | Owen dies at age 88. His reputation had suffered due to his feuds with Darwin’s supporters, but his museum remains the world’s premier center for paleontology. |

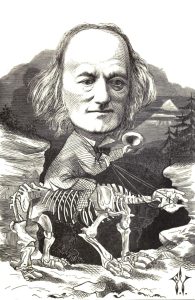

Richard Owen History

Caricature of Owen “riding his hobby”, by Frederick Waddy (1873).

(Wiki Image By Frederick Waddy – archive.org, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12451986)

The history of Sir Richard Owen is a Shakespearean tragedy of science. He was arguably the most brilliant biological mind of the 19th century—the man who taught Queen Victoria’s children and gave the world the word “Dinosaur.” Yet, his legacy was tarnished by arrogance, jealousy, and a refusal to accept the theory of evolution.

Here is the history of the man known as “The British Cuvier.”

1. The Surgeon’s Apprentice (1804–1827)

Born in Lancaster, England, Owen did not initially pursue a career in paleontology. He began as a surgeon’s apprentice.

- The Macabre Beginning: He had a grim talent for dissection. There are stories of him as a young student carrying severed heads in bags to study their brains.

- The Shift: He eventually realized he was more interested in how the body worked than in healing it. He moved to London to work at the Royal College of Surgeons.

2. The “Cleanup” Man (1827–1840)

Owen’s genius was forged in the chaos of the Hunterian Collection.

- The Task: The famous surgeon John Hunter had died, leaving behind thousands of uncatalogued specimens (jars of organs, skeletons, dried tissues). Owen’s job was to identify and organize them.

- The Skill: By handling thousands of different animal parts, Owen developed a remarkable ability to identify homology (patterns). He could examine a single bone and immediately determine what animal it came from and how it lived.

- The Zoo: He became the unofficial dissector for the London Zoo. If a lion, rhino, or giraffe died, Owen got the body.

3. The Golden Age (1840–1855)

This was the period when Owen could do no wrong. He became the most famous scientist in Britain.

- The Moa (1839): He famously predicted the existence of a giant flightless bird in New Zealand based on a single fragment of thigh bone. When the full skeleton was found four years later, he became a celebrity.

- Dinosauria (1842): He realized that the giant lizards found in England were a distinct group and named them “Dinosauria.”

- The Crystal Palace (1854): He acted as the consultant for the world’s first dinosaur theme park, dining inside the mold of an Iguanodon on New Year’s Eve.

4. The “Villain” of Evolution (1859–1870)

When Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, Owen’s career took a dark turn.

- The Rivalry: Owen had helped Darwin identify his fossils, so he felt betrayed that Darwin proposed a theory (Natural Selection) that removed God from the process.

- The Anonymous Attacks: Owen wrote scathing, anonymous reviews of Darwin’s book, praising himself while tearing down Darwin.

- The “Hippocampus Question”: In an attempt to prove humans were special, Owen claimed the human brain had a structure (the hippocampus minor) that apes lacked. Thomas Huxley publicly dissected an ape brain and proved Owen was lying (or incompetent). It was a humiliating public defeat.

5. The Redemption: The Cathedral of Nature (1881)

Despite his fall from grace in the theoretical world, Owen achieved one final, massive victory.

- The Campaign: He hated that Britain’s natural treasures were rotting in the basement of the British Museum. He campaigned for a separate building.

- The Result: He oversaw the construction of the Natural History Museum in South Kensington. He designed it to resemble a cathedral, using terracotta tiles that could be washed clean of London’s soot.

- The Vision: He ensured the museum was free to the public, believing that the study of nature should be accessible to everyone, not just the elite.

Summary

Richard Owen is often remembered today as the man who fought Darwin. However, without his obsession with classification, anatomy, and museum-building, the science of paleontology would likely have remained a disorganized hobby for decades longer. He built the “house” that Darwin eventually filled with “furniture.”

Richard Owen 8 Top Paleontology Contributions

While Sir Richard Owen is often remembered today as the “villain” who fought Charles Darwin (and stole credit from Gideon Mantell), he was arguably the most brilliant comparative anatomist of the 19th century.

Without Owen’s obsession with order and classification, the chaotic piles of bones found by people like Mary Anning would never have been organized into a coherent history of life.

Here are the Top 8 Contributions of the man who named the Dinosaurs.

- Coining “Dinosauria” (1842)

- The Act: In a report to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Owen reviewed the bones of Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus.

- The Insight: He noticed that their sacrum (the hip vertebrae) was fused. This meant they didn’t sprawl like lizards; they held their legs directly under their bodies (like mammals).

- The Name: He grouped them into a distinct sub-order: Dinosauria (“Fearfully Great Lizards”).

- The Impact: This turned isolated curiosities into a “Dynasty.” It proved that reptiles were once the dominant, advanced life form on Earth, not just “overgrown lizards.”

- The Concept of “Homology” (1843)

- The Definition: Owen defined the difference between Homology (same organ, different function) and Analogy (different organ, same function).

- The Example: He showed that a human hand, a bat’s wing, and a whale’s fin all have the exact same bone structure (homology), even though they do different things.

- The Irony: Owen used this to argue for a “Divine Plan” (God used a blueprint). However, Charles Darwin later used Owen’s proof of homology as the strongest evidence for Common Ancestry (Evolution).

- The “Moa” Deduction (The Sherlock Holmes Moment) (1839)

- The Challenge: A sailor brought Owen a single, fragmented piece of a thigh bone from New Zealand. It looked featureless and unidentifiable.

- The Prediction: Based on the texture of the bone alone, Owen boldly predicted that it belonged to a giant, flightless bird that had gone extinct. The scientific community mocked him.

- The Vindication: Four years later, crates of bones arrived from New Zealand containing the complete skeletons of the Moa (Dinornis). Owen was exactly right. This feat made him a celebrity, known as the man who could “reconstruct an animal from a single bone.”

- Creating the Natural History Museum (1881)

- The Problem: In the mid-1800s, fossils were stored in the British Museum’s basement, where they were decaying and disorganized.

- The Solution: Owen campaigned for decades to give nature its own “Cathedral.” He sketched a grand museum where even the poorest person could walk in and see the “Works of God.”

- The Legacy: He founded the Natural History Museum in South Kensington (London). It remains one of the world’s premier scientific institutions.

- The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs (1854)

- The Project: Owen partnered with artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins to create the world’s first life-sized dinosaur sculptures for the Crystal Palace Park in London.

- The Look: He depicted them as heavy, rhino-like quadrupeds.

- The Impact: While scientifically inaccurate today, this was the first time the public ever saw a dinosaur. It sparked “Dinomania,” moving paleontology from dusty academic papers to pop culture.

- Describing Darwin’s “Lost Giants” (1837–1845)

- The Context: When a young Charles Darwin returned from the voyage of the HMS Beagle, he had crates of strange South American fossils he couldn’t identify. He brought them to Owen.

- The Identification: Owen identified them as the Toxodon (a giant rodent-like hoofed mammal), the Glyptodon (a giant armadillo), and the Macrauchenia.

- The Impact: Owen demonstrated that these were extinct giant forms of animals still living in South America. This “Law of Succession” was a key clue that helped Darwin formulate the theory of evolution.

- The “London Specimen” (Archaeopteryx) (1863)

- The Specimen: When the first high-quality Archaeopteryx fossil was found in Germany, Owen secured it for the British Museum (for a massive sum of £700).

- The Description: He wrote the definitive anatomical description of it.

- The Flaw: True to his anti-evolution bias, Owen described it merely as a “bird with a long tail,” failing to recognize that it was the transitional link between dinosaurs and birds. However, his detailed description allowed others (like Thomas Huxley) to prove that link.

- The Mammal-Like Reptiles (Therapsids) (1845)

- The Find: Soldiers and surveyors in South Africa began sending Owen skulls with two large tusks.

- The Discovery: Owen named them Dicynodonts (“Two Dog Tooth”).

- The Significance: He recognized that these were reptiles with mammal-like features. He successfully identified the group (Synapsids/Therapsids) from which all mammals (and humans) eventually evolved, filling a massive gap in the tree of life.

Would you like to see how Owen used “Homology” to argue against evolution, or perhaps examine the specific rivalry in which Thomas Huxley used Owen’s own data to defeat him?

Richard Owen, Coining “Dinosauria” (1842)

In 1842, Sir Richard Owen changed the course of history with a single word. He took the scattered, confusing bones of “giant lizards” that had puzzled scientists and unified them into a distinct biological group: Dinosauria.

This was not just a naming ceremony; it was a radical scientific argument that reptiles were once the dominant, advanced life forms on Earth.

The “Three Foundation Stones”

Owen didn’t have thousands of specimens like we do today. He built the entire concept of “The Dinosaur” based on just three specific animals that had been found in England:

- Megalosaurus (“Great Lizard”): The carnivore jaw found by Buckland.

- Iguanodon (“Iguana Tooth”): The herbivore teeth found by the Mantells.

- Hylaeosaurus (“Forest Lizard”): The armored ankylosaur found by Mantell.

The Anatomical Breakthrough: The Sacrum

Owen was a comparative anatomist, meaning he looked for structural patterns. When he examined the spines of these three animals, he noticed a specific, shared trait that modern lizards (such as iguanas and crocodiles) lack.

- The Feature: The Sacrum (the section of the spine that connects to the hips) was composed of five fused vertebrae.

- The Meaning: In modern lizards, the sacrum is weak because they sprawl (legs out to the side). A fused, solid sacrum is only found in large mammals (like elephants) that need to support massive weight.

- The Conclusion: Owen realized these creatures did not crawl on their bellies. They walked with their legs directly under their bodies, more like a rhino or a horse than a lizard.

The Name: “Fearfully Great”

Because they stood upright and had mammal-like posture, Owen argued they deserved a higher rank than ordinary reptiles.

- The Greek: Deinos (Fearful / Terrible / Great) + Sauros (Lizard).

- The Meaning: While often translated as “Terrible Lizard,” Owen intended it to mean “Fearfully Great”—referring to their majestic size and dominance, not just that they were scary.

The Vision: The “Super-Reptile”

Owen used this classification to oppose early ideas of evolution (transmutation).

- The Argument: Evolutionists believed that life started simple and got more complex. Owen argued that Dinosaurs were more complicated and advanced than modern reptiles.

- The Implication: If the “ruling reptiles” of the past were superior to the “crawling reptiles” of today, then life had degenerated, not evolved. (Darwin would later refute this, but at the time, it was a powerful argument.)

The Legacy: The Crystal Palace

To cement this new name in the public mind, Owen commissioned the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs (1854). He designed them based on his “Mammal-like Reptile” theory—giving them the heavy legs of elephants and the bulk of rhinoceroses, a look that defined dinosaurs for the next century.

The concept of “Dinosauria,” coined by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, is best visualized not only by its name but also by the early, influential reconstructions he commissioned. These images captured his key scientific insight: that dinosaurs walked upright like mammals, not sprawled like lizards.

Here is an image that visualizes the three foundation specimens Owen used and his grand new classification:

This image typically features:

- The Original Three: Illustrations or depictions of the fragmented bones of the first three species: Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus.

- The Upright Posture: Diagrams or early illustrations commissioned by Owen that show his radical conclusion: that these reptiles stood with their legs straight under their bodies, a trait he deduced from the five fused vertebrae of their sacrum.

- The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs: The image may also reference the iconic, early, elephantine sculptures created for the Crystal Palace, which were the ultimate physical expression of Owen’s “Fearfully Great Lizard” concept.