🌊 Tyre (332 BC), 🔧 Syracuse (213–212 BC), 🌀 Alesia (52 BC), ⛰️ Masada (73 AD), and ⚔️ Acre (1189–1191): Ancient Sieges

Here is a breakdown of five of history’s most technically complex and dramatic sieges, ranging from the campaigns of Alexander the Great to the Crusades.

1. 🌊 The Siege of Tyre (332 BC)

“The Impossible Island”

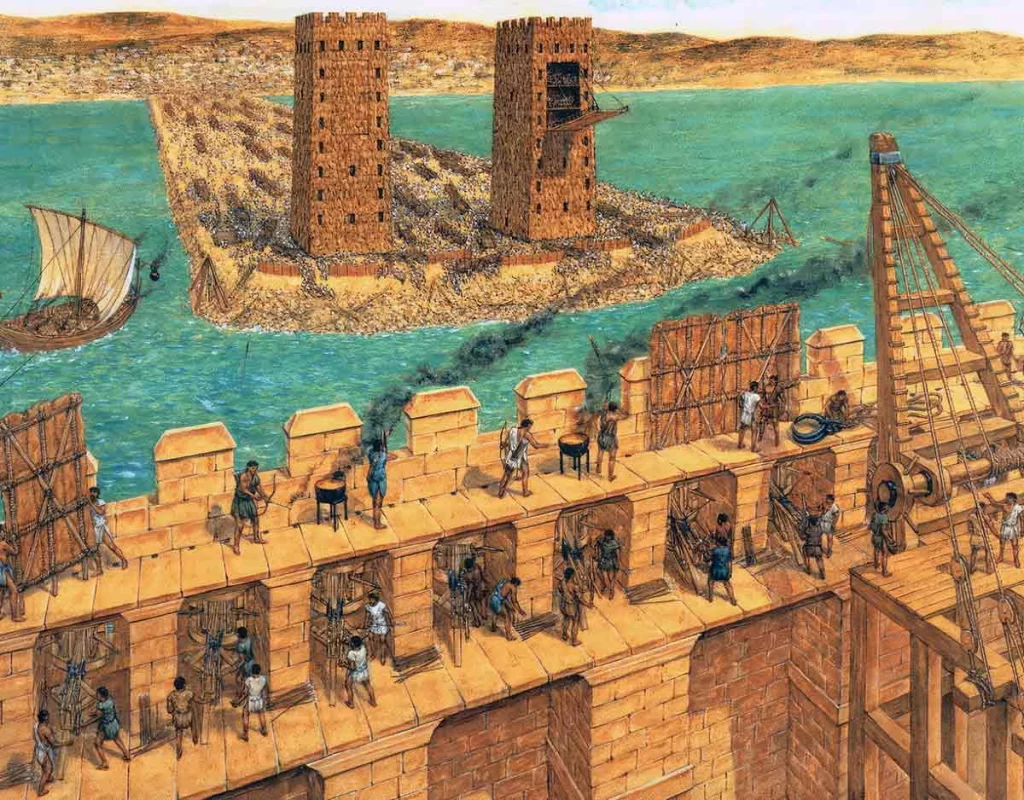

Alexander the Great faced a unique problem: Tyre was an island fortress 1 km off the coast of modern-day Lebanon, with walls reaching 150 feet high that extended into the sea. He had no navy to challenge them.

- Belligerents: Macedonians (Alexander the Great) vs. Phoenicians (Tyre).

- The Engineering Feat: Since he couldn’t sail to the walls, Alexander decided to bring the mainland to the island. He ordered his engineers to build a massive causeway (mole) 200 feet wide across the ocean channel.

- The Counter-Tactics: The Tyrians were ingenious defenders. They sent divers to cut the anchor cables of Alexander’s siege ships. They floated a “fireship” (a cauldron of burning sulfur and bitumen) into the Macedonian siege towers, which then burned down.

- The Outcome: Alexander eventually gathered a fleet from conquered allies, blockaded the harbor, and smashed the walls. The city was sacked brutally; 2,000 military-age men were crucified along the beach.

- Legacy: The mole Alexander built remains; over centuries, silt accumulated around it, permanently transforming Tyre from an island into a peninsula.

2. 🔧 The Siege of Syracuse (213–212 BC)

“The Duel of Minds”

This siege pitted the might of the Roman legions against the genius of a single mathematician: Archimedes.

- Belligerents: The Roman Republic (Marcus Claudius Marcellus) vs. The City of Syracuse (Greek colony in Sicily).

- The “Math” Defense: Archimedes designed terrifying defensive engines.

- The Claw: A giant crane with a grappling hook that could lift Roman ships out of the water and drop them, capsizing them.

- The Mirrors (Legend): Stories claim he used bronze mirrors to focus sunlight and set Roman sails on fire (though physicists debate this).

- Steam Cannon: Some texts suggest a steam-powered device that fired clay projectiles.

- The Outcome: The Romans were initially humiliated and forced to switch to a starvation blockade. They finally breached the city during a festival when guards were drunk. Despite Marcellus’s orders to capture Archimedes alive, a Roman soldier killed the 75-year-old mathematician while he was drawing circles in the sand.

3. 🌀 The Siege of Alesia (52 BC)

” The Doughnut Fortification”

Julius Caesar’s masterpiece of field engineering. He trapped Vercingetorix, but was then trapped himself.

- Belligerents: Roman Republic (Julius Caesar) vs. Gallic Confederation (Vercingetorix).

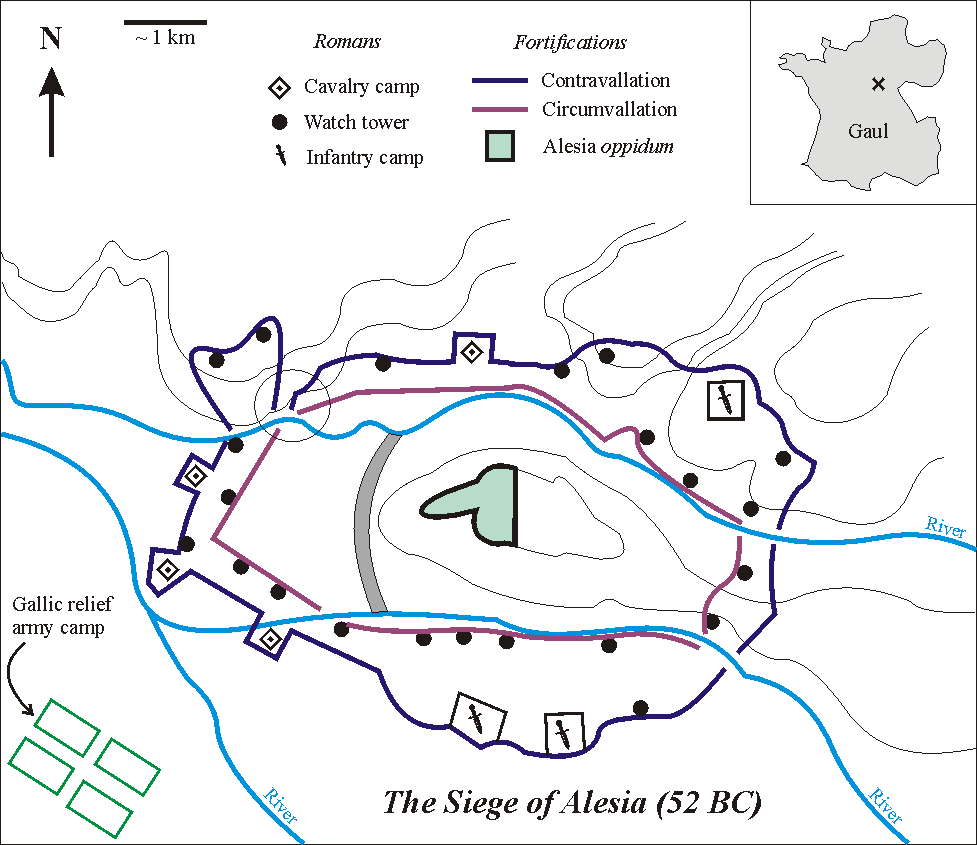

- The Double Wall: Caesar built two lines of fortifications:

- Circumvallation (Inner Ring): 10 miles long, facing inward to keep Vercingetorix in.

- Contravallation (Outer Ring): 13 miles long, facing outward to keep the massive Gallic relief army out.

- The “Garden of Death”: Between the walls, Caesar dug pits filled with sharpened stakes (“lilies”), flooded trenches, and hidden iron hooks to maim attackers.

- The Outcome: Caesar’s starving troops held off 80,000 men from the inside and supposedly 250,000 from the outside. Vercingetorix surrendered his armor at Caesar’s feet, marking the end of Gallic independence.

4. ⛰️ The Siege of Masada (73 AD)

“The Symbol of Resistance”

The final act of the First Jewish-Roman War took place on top of a lonely rock plateau in the Judean Desert.

- Belligerents: Roman Empire (Legion X Fretensis) vs. Jewish Sicarii (Eleazar ben Ya’ir).

- The Geography: The fortress sat on a mesa 1,300 feet high with sheer cliffs on all sides.

- The Ramp: The Romans, unable to use standard towers, spent months building a massive earthen ramp up the side of the mountain. They used Jewish prisoners to make it so the defenders wouldn’t shoot at the workers.

- The Outcome: When the Romans finally rolled their battering ram up the completed ramp and breached the wall, they found silence. The 960 defenders had chosen mass suicide rather than enslavement. Only two women and five children survived to tell the story.

5. ⚔️ The Siege of Acre (1189–1191)

“The Deadliest Stalemate”

A grueling, two-year grinder that served as the focal point of the Third Crusade.

- Belligerents: Crusaders (Guy of Lusignan, Richard the Lionheart, Philip II) vs. Ayyubid Dynasty (Saladin).

- The Situation: A “siege within a siege.” The Crusaders besieged the Muslim garrison in the city, while Saladin’s army surrounded the Crusaders from the outside.

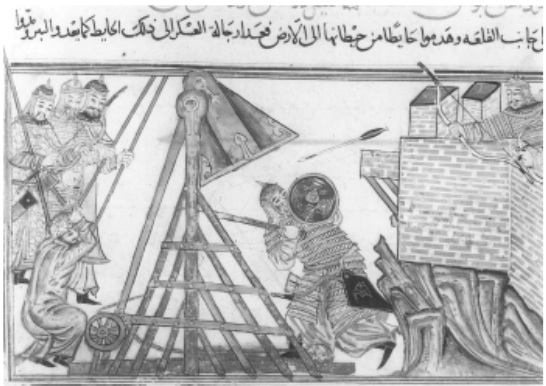

- The Tech:

- Greek Fire: The Muslim defenders used pots of flammable liquid to destroy Crusader siege towers (including three massive towers built by the kings).

- Bad Neighbor: The name of a massive stone-throwing trebuchet used by the Crusaders to pound the “Accursed Tower.”

- The Outcome: The arrival of Richard the Lionheart and Philip II tipped the balance. The city surrendered. The victory allowed the Crusaders to secure the coast, but Richard later executed roughly 2,700 Muslim prisoners when ransom negotiations stalled, a massacre that marred the victory.

Summary Comparison

| Siege | Date | Victor | Key Feature |

| Tyre | 332 BC | Alexander | Building a land bridge (mole) across the ocean. |

| Syracuse | 212 BC | Rome | Defeated by the inventions of Archimedes (The Claw). |

| Alesia | 52 BC | Caesar | The double wall (fighting simultaneously inside and outside). |

| Masada | 73 AD | Rome | The massive earthen ramp up a cliff face. |

| Acre | 1191 | Crusaders | The “siege within a siege” and use of Greek Fire. |

🌊 The Siege of Tyre (332 BC)

Alexander’s siege of Tyre

https://www.thecollector.com/siege-of-tyre-alexander-the-great/

🌊 The Siege of Tyre Quotes

The Siege of Tyre was such a monumental event that it was recorded by several major ancient historians, primarily Arrian, Curtius Rufus, Diodorus Siculus, and Plutarch. Their accounts provide a vivid window into the psychological warfare, the engineering desperation, and Alexander’s relentless willpower.

Here are the most significant quotes regarding the siege, categorized by its different phases.

🏛️ The Prelude: The “Sacrifice” Ultimatum

Alexander’s pretext for the war was his desire to sacrifice to Melqart (Heracles). The Tyrians’ refusal set the stage for the conflict.

“Alexander sent envoys to say that he wished to sacrifice to Heracles in his temple on the island. The Tyrians replied that there was a temple of Heracles in the old city on the mainland… but that they would not admit any Macedonian or Persian into their city.” — Arrian, The Anabasis of Alexander

“Alexander, losing his temper, as was his nature, at this refusal, sent the envoys away with threats, and immediately began to prepare for the siege.” — Curtius Rufus, History of Alexander

🏗️ The Engineering: Building the Mole

The historians were stunned by the sheer scale of the labor required to bridge the sea.

“The work was not easy; for the sea was deep at that point, and the mud was of such a nature that the stones were swallowed up as fast as they were thrown in.” — Curtius Rufus

“Alexander himself was the first to take up a basket and carry earth; and when the Macedonians saw their king working with his own hands, they followed his example with enthusiasm.” — Arrian

🔥 The Tyrian Resistance: Mechanical Ingenuity

The Tyrians were famous for their inventiveness in defense, frustrating the Macedonians at every turn.

“They [the Tyrians] heated sand in large bronze shields until it was red-hot, and then by means of a machine threw it over those who were fighting… it got under their breastplates and burnt their flesh.” — Diodorus Siculus, Library of History

“The Tyrians also made use of ‘crows’ and ‘iron hands’ to snatch the men from the towers and drag them over the walls into the city.” — Curtius Rufus

🌊 The Naval Turning Point

Alexander’s realization that he needed ships changed the course of the war.

“Alexander saw that he would never take the city as long as the Tyrians were masters of the sea.” — Arrian

“When the Tyrians saw the vast number of ships approaching from Sidon, they were struck with terror; for they had not expected that Alexander would be able to collect such a fleet so quickly.” — Arrian

⚔️ The Final Assault: The King’s Fury

The breach of the walls and the subsequent massacre were described with brutal clarity.

“Alexander himself was seen on the top of the wall, fighting with the greatest bravery… he was the first to leap into the city, followed by the Hypaspists.” — Arrian

“The king gave orders to kill all the inhabitants except those who had fled to the temples… the number of those slain was six thousand.” — Curtius Rufus

⚖️ The Legacy: A City Changed Forever

Perhaps the most famous “quote” is the geographical reality that remains today.

“Tyre, which was an island, was now made a peninsula by the mound of Alexander.” — Pliny the Elder, Natural History

Would you like me to…

- Contextualize a specific quote from one of these historians to explain the military tactic it refers to?

- Compare the Tyrian defense machines to the “Claw” of Archimedes at Syracuse?

- Explore the speech Alexander gave to his troops to convince them not to give up on the mole.

🌊 The Siege of Tyre (332 BC) Prehistory

The “prehistory” of the Siege of Tyre (332 BC) is a study in the collision between an unstoppable land power—Alexander the Great’s Macedonian army—and an impregnable maritime fortress. It examines the strategic landscape of the Levant following Alexander’s victory at Issus and the unique historical-geographic identity of Tyre, which made it a formidable obstacle.

- The Strategic Vacuum: Post-Issus (333 BC)

After Alexander defeated the Persian King Darius III at the Battle of Issus, the Persian Empire did not immediately collapse. However, the Mediterranean coastline (Phoenicia) became the critical strategic theater.

- Neutralizing the Persian Navy: The Persian fleet, manned mainly by Phoenician sailors, dominated the sea. Alexander lacked a significant navy; his only means of defeating the Persian fleet was to “capture it from the land” by seizing every port city that supplied its ships and crews.

- The Submission of Phoenicia: Most Phoenician cities, such as Byblos and Sidon, surrendered to Alexander without a fight, seeking to preserve their trade interests. Tyre, however, pursued a middle-ground diplomatic approach that Alexander found unacceptable.

- The Island Fortress: Geography as Armor

Tyre was not a single city but two. There was “Old Tyre” on the mainland, and “New Tyre,” located on an island roughly 800 meters (half a mile) offshore.

- The Walls: The island city was encircled by massive stone walls that reportedly reached 45 meters (150 feet) in height on the landward side.

- The Harbors: It possessed two deep-water harbors—the “Sidonian” harbor to the north and the “Egyptian” harbor to the south—allowing it to be resupplied by sea indefinitely.

- The Fleet: Unlike the cities that had already surrendered, the Tyrian navy remained intact and loyal to the island, making any ship-borne assault by Alexander impossible at the start of the campaign.

- The Diplomatic Insult

Alexander initially sent envoys to Tyre, stating he wished to enter the island city to offer a sacrifice to Melqart (whom the Greeks identified with Heracles).

- The Tyrian Refusal: The Tyrians, savvy diplomats who had survived previous sieges by the Assyrians and Babylonians, saw through the ruse. They told Alexander he could sacrifice at the temple in Old Tyre on the mainland, but no Macedonian would be permitted on the island.

- The Breaking Point: Alexander saw this “neutrality” as a direct threat to his rear as he moved toward Egypt. When he sent a second group of envoys, the Tyrians executed them and threw their bodies from the walls into the sea. This act shifted the mission from strategic necessity to a personal quest for destruction.

- The Engineering Gamble

Alexander’s plan to conquer Tyre was unprecedented in the history of warfare. Since he had no navy to bridge the gap to the island, he decided to change the geography of the world.

- The Mole: He ordered the construction of a massive stone causeway (a “mole”) that would stretch from the mainland all the way to the island walls.

- Materials: To build this, Alexander literally dismantled “Old Tyre,” using the rubble of the mainland city and timber from the forests of Lebanon to fill the sea.

- Summary Table: The Setup for Siege

| Factor | Macedonian Status | Tyrian Status |

| Command of the Sea | None; zero naval assets in the region. | Total; protected by the Phoenician fleet. |

| Logistics | Dependent on captured land routes. | Indefinite; sea lanes open for food and water. |

| Defense Strategy | Aggressive engineering (The Mole). | Passive-aggressive defense (The Walls). |

| Historical Precedent | Never faced a fortress of this scale. | Survived a 13-year siege by Nebuchadnezzar II. |

- The Psychological Landscape

The Tyrians relied on the historical fact that no one had ever successfully taken their island by force. They believed Alexander was a “land-bound” conqueror who would eventually grow frustrated and march on toward Egypt or Babylon. They did not anticipate Alexander’s willingness to expend seven months and thousands of lives to turn an island into a peninsula—a geographic change that remains visible to this day.

🌊 The Siege of Tyre Chronological Table

The city of Tyre/Sour in Southern Lebanon photographed from the International Space Station (ISS). Image courtesy of the Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, NASA Johnson Space Center: https://eol.jsc.nasa.gov/

(Wiki Image By Image courtesy of the Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, NASA Johnson Space Center – https://eol.jsc.nasa.gov/SearchPhotos/photo.pl?mission=ISS006&roll=E&frame=31938, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=97774377)

🌊 The Siege of Tyre (332 BC): Chronological Table

Below is a clear, step-by-step timeline of Alexander the Great’s most audacious siege, showing how an “impossible” island fortress was taken through engineering, persistence, and brutality.

| Phase | Date (332 BC) | Event | Significance |

| 1. Strategic Decision | Spring | Alexander marches south after Issus and demands Tyre’s surrender | Tyre refuses, confident in its island defenses and navy |

| 2. Initial Assessment | Spring | Alexander realizes Tyre sits ~1 km offshore with walls rising directly from the sea | Traditional siege towers and rams are useless |

| 3. Construction of the Mole Begins | Spring–Early Summer | Macedonians begin building a massive stone causeway from the mainland | A revolutionary solution: “bring the land to the island.” |

| 4. Tyrian Naval Harassment | Early Summer | Tyrian ships attack workers and siege equipment | Shows Tyre’s naval superiority |

| 5. Fire Ship Attack | Early Summer | Tyrians send a fire ship loaded with sulfur and pitch into the siege towers | Macedonian siege towers are destroyed |

| 6. Alexander Regroups | Mid-Summer | Alexander gathers fleets from Phoenician cities (Sidon, Byblos, Cyprus) | Naval balance shifts decisively |

| 7. Naval Blockade Established | Mid-Summer | Macedonian fleet blockades both Tyrian harbors | Cuts off supplies and reinforcements |

| 8. Mole Completed | Late Summer | Causeway reaches Tyre’s walls | Allows direct assault on fortifications |

| 9. Artillery Bombardment | Late Summer | Catapults and ballistae batter the southern wall | Walls begin to crumble |

| 10. Breach of the Walls | July | Macedonian forces create a breach | Turning point of the siege |

| 11. Final Assault | July | Simultaneous land and sea attack | Overwhelms Tyrian defenders |

| 12. Sack of Tyre | July | City falls after ~7 months | 8,000 killed; ~30,000 enslaved |

| 13. Aftermath | Post-Siege | 2,000 Tyrian men crucified along the shore | Psychological warfare for future cities |

| 14. Geological Legacy | Long-term | Sediment accumulates around the mole | Tyre permanently becomes a peninsula |

🧱 Why Tyre Matters

- Engineering First: The mole remains one of history’s most extraordinary military engineering feats.

- Naval Warfare: Demonstrates Alexander’s adaptability beyond land battles.

- Psychological Impact: The brutality ensured that future coastal cities surrendered without resistance.

- Permanent Geography Change: Few sieges literally reshape the map.

If you’d like, I can also:

- Compare Tyre directly with Alesia or Masada

- Break this into engineering vs. naval vs. artillery phases

- Create a visual ASCII siege diagram

- Or write a “day-by-day” siege narrative

Just say the word ⚔️

🌊 The Siege of Tyre History

The Phoenician city of Tyre was one of the best-fortified cities in history. It was also crucial to Alexander the Great’s plans to conquer the Persian Empire.

https://www.thecollector.com/siege-of-tyre-alexander-the-great/

The Siege of Tyre in 332 BC is regarded as the most challenging and brilliant military operation of Alexander the Great’s career. For seven months, the Macedonian king was forced to transform from a cavalry commander into a master of naval warfare and civil engineering to conquer a city that many believed was physically unreachable.

🏛️ The Strategic Necessity

After defeating the Persian King Darius III at the Battle of Issus, Alexander moved south along the Mediterranean coast. Most Phoenician cities surrendered, but the island of Tyre—the primary naval base for the Persian Empire—refused.

- The Ultimatum: Alexander wished to offer a sacrifice at the Temple of Melqart (whom the Greeks identified as Heracles). The Tyrians, trusting their island’s 800-meter distance from the shore and its 150-foot-high walls, suggested he use the temple on the mainland instead.

- The Risk: Alexander could not march toward Egypt while leaving a hostile Persian naval power behind him. He needed to “conquer the sea from the land” by capturing the Tyrian fleet’s home port.

🏗️ Phase I: The Great Mole (Land Bridge)

Because Alexander lacked a navy, his engineers, led by Diades of Pella, began one of the most ambitious construction projects of antiquity: building a land bridge (a mole) from the mainland to the island.

- The Construction: Macedonians dismantled the buildings of “Old Tyre” on the mainland to use as stone. They harvested cedar from Mount Lebanon for piles to drive into the sea floor.

- The Setback: As the mole reached deeper water, it became vulnerable. The Tyrians launched a specialized fire ship—a vessel packed with sulfur, pitch, and dry wood—and crashed it into the Macedonian siege towers at the end of the mole, burning months of work in a single day.

⚓ Phase II: The Naval Turning Point

Realizing the mole would never be finished under constant naval harassment, Alexander traveled to Sidon and Byblos to assemble a fleet of his own.

- The Armada: He gathered 223 ships, including fleets from Cyprus and Rhodes. This shifted “Command of the Sea” to the Macedonians.

- The Blockade: Alexander split his fleet to blockade Tyre’s two harbors: the Sidonian Harbor to the north and the Egyptian Harbor to the south.

- Underwater Warfare: The Tyrians dropped massive boulders into the sea to prevent Alexander’s ships from approaching the walls. Alexander used specialized crane ships to winch these rocks out of the water and dump them into the deep sea.

☄️ Phase III: Innovation in Artillery

With the sea under his control, Alexander pioneered the use of naval artillery.

- Floating Batteries: He lashed pairs of triremes together to create stable catamaran platforms.

- Torsion Engines: On these platforms, he mounted heavy torsion catapults and battering rams. This allowed him to probe the 2-mile circumference of the city walls, searching for a weak point that was not as heavily fortified as the landward side.

⚔️ The Final Breach and Fall

In July 332 BC, Alexander identified a “soft spot” on the southern sea wall.

- The Barrage: Ship-mounted catapults pounded the wall until a section collapsed.

- The Bridges: Specialized ships equipped with boarding bridges (wide gangplanks) were steered into the rubble.

- The Assault: Alexander personally led the elite Hypaspists across the bridges and onto the battlements. Once the wall was taken, the Macedonian navy snapped the harbor chains and flooded the city from all sides.

⚖️ The Outcome and Legacy

A brutal massacre followed the fall of Tyre, as Alexander was enraged by the length of the siege and the execution of Macedonian prisoners on the walls.

- Statistics: Approximately 6,000 Tyrians died in battle; 2,000 men were crucified along the shore; and 30,000 citizens were sold into slavery.

- Geographical Change: The mole was so massive that sand accumulated against it over centuries. Today, Tyre is no longer an island but a peninsula, a permanent topographical scar left by Alexander’s ambition.

Would you like me to…

- Provide a technical breakdown of the torsion catapults used in the siege?

- Analyze the Siege of Gaza, which Alexander undertook immediately after Tyre.

- Explore the archaeological discoveries found beneath the waters surrounding the mole?

🌊 The Siege of Tyre (332 BC): 8 top essential aspects, including technology, engineering, tactics, strategy, artillery, infantry, cavalry, plague, religion, logistics, walls, manpower, and length.

Alexander’s Coordinated Attack

https://www.thecollector.com/siege-of-tyre-alexander-the-great/

Siege of Tyre (332 BC) is often cited as the pinnacle of Alexander the Great’s military and engineering career. It was a confrontation that defied the traditional boundaries of ancient warfare, requiring the Macedonian king to quite literally reshape the geography of the Mediterranean.

To provide a comprehensive analysis, we break the siege into eight essential pillars: the strategic necessity of the island, the construction of the Great Mole, the naval revolution at Sidon, the application of torsion artillery, the defense-shattering siege towers, the tactical breach of the southern wall, the logistics of a Mediterranean coalition, and the brutal religious and political outcome.

1. Strategy: The Impregnable Island Fortress 🏝️

Tyre was a strategic “locked door” that Alexander had to open to secure his conquest of the Persian Empire.

- The Geographic Challenge: The “New City” of Tyre was located on an island roughly 800 meters (half a mile) off the coast of modern-day Lebanon. It was protected by massive walls reaching 150 feet in height on the landward side, making a traditional land assault impossible.

- The Persian Naval Threat: Alexander’s grand strategy involved “conquering the sea from the land.” He lacked a navy, but he knew that as long as Tyre remained a sovereign Persian naval base, the Tyrian fleet could harass his supply lines to Greece and potentially incite a revolt in his rear.

- The Ultimatum: Alexander initially sought a peaceful resolution by asking to sacrifice at the Temple of Melqart (Heracles). The Tyrians, confident in their island’s safety, refused. This “religious insult” gave Alexander the pretext for a total war of annihilation.

- The Commitment: Unlike other leaders who might have bypassed the island, Alexander understood that leaving Tyre undefeated would signal weakness to the Egyptian satraps and the remaining Persian provinces.

2. Engineering: The Great Mole (Land Bridge) 🏗️

Since Alexander could not sail to Tyre, he decided to bring the land to the island. This resulted in one of the most famous engineering feats in antiquity.

- Construction Process: Alexander ordered his troops and local laborers to build a mole (causeway) 200 feet wide across the sea.

- The “Stone-Eater”: To provide the material, Alexander ordered the complete demolition of “Old Tyre” on the mainland. Every stone, brick, and piece of timber from the old city was hauled to the shore and dumped into the Mediterranean.

- Foundation Work: To stabilize the mole in the shifting seabed, thousands of cedar piles were harvested from Mount Lebanon and driven into the mud.

- The Deep Water Crisis: As the mole reached deeper water, the current intensified, and the work became more hazardous. The Tyrian navy began constant harassment, firing arrows and stones at the workers, forcing Alexander to move from simple construction to combat engineering.

3. Technology: The Giant Siege Towers 🗼

To protect the workers on the mole from the 150-foot walls of Tyre, Alexander’s engineers, led by Diades of Pella, developed the most advanced siege towers of the era.

- Specifications: Alexander built two towers at the end of the mole, each approximately 150 feet (45 meters) tall, matching the height of the Tyrian walls.

- The “Skin” of the Tower: To counter the primary threat of fire, the wooden frames were covered in rawhide and wet animal skins. This served as a rudimentary fireproofing measure, absorbing the impact of incendiary arrows.

- Artillery Platforms: These towers weren’t just for scaling; they were mobile fortresses. The lower levels housed massive battering rams, while the upper levels housed tension- and torsion-powered engines to breach the walls.

- The Fire Ship Counter: The Tyrians launched a specialized fire ship—a transport vessel filled with sulfur and pitch—and crashed it into the towers. The resulting inferno destroyed Alexander’s first set of towers, forcing him to realize that the mole alone would never win the city.

4. Navy: The Turning Point at Sidon ⚓

The realization that “the mole needs a navy” led to the most significant diplomatic and naval shift in the campaign.

- The Diplomatic Mission: Alexander traveled to Sidon and Byblos. Because he had already captured the home ports of the Phoenician sailors serving in the Persian navy, their loyalty shifted.

- The Coalition Armada: Alexander returned with a fleet of 223 ships, including 80 Phoenician ships and 120 Cypriot ships. This gave him “Command of the Sea” for the first time.

- The Harbor Blockade: Alexander split his fleet to blockade Tyre’s two harbors: the Sidonian Harbor (north) and the Egyptian Harbor (south).

- Underwater Demolition: The Tyrians had dropped massive boulders into the sea to prevent ships from approaching the walls. Alexander used specialized crane ships to winch these boulders out of the water and dump them in the deep sea, clearing a path for his artillery ships.

5. Artillery: Ship-Mounted Torsion Engines ☄️

Once Alexander controlled the sea, he pioneered the use of naval artillery, a technology that would dominate Mediterranean warfare for centuries.

- The Catamarans: Standard galleys were too narrow for large catapults. Alexander’s engineers lashed pairs of triremes together to create wide, stable catamaran platforms.

- Torsion Power: These ships were equipped with torsion catapults that used twisted bundles of animal sinew. This enabled them to launch stones weighing more than 100 pounds with sufficient force to crack stone masonry.

- Mobile Battering Rams: He also mounted battering rams on ships. This allowed him to test every inch of the 2-mile circumference of the Tyrian walls, searching for a weak point less heavily reinforced than the landward side facing the mole.

6. Tactics: The Breach and the Bridges ⚔️

The final assault in July 332 BC was a masterful example of synchronized, multi-directional tactics.

- The Three-Pronged Attack: Alexander launched a simultaneous assault on the northern harbor, the southern harbor, and the landward mole to stretch the Tyrian defenses to the breaking point.

- The Southern Breach: His ship-mounted rams finally battered down a section of the southern wall.

- Boarding Bridges: Alexander used specialized ships equipped with boarding bridges (wide gangplanks). As soon as the wall crumbled, these bridges were lowered onto the rubble.

- The Hypaspist Charge: Alexander personally led the elite Hypaspists (shield-bearers) across the bridge. His presence on the battlements broke the Tyrian morale, leading to a total collapse of the city’s perimeter.

7. Logistics and Manpower: The Mediterranean Coalition 👥

The siege was a massive administrative effort that required the resources of three different cultures.

- Manpower Scale: Alexander managed a force of approximately 35,000–40,000 soldiers, plus thousands of Phoenician and Cypriot sailors and engineers.

- Supply Lines: Feeding 50,000 men on a barren coast required a constant stream of grain from Galilee and Samaria. Alexander had to lead “foraging raids” into the Arab-controlled interior to prevent his army from starving during the seven-month investment.

- Industrial Production: Massive field workshops were set up on the shore to manufacture the thousands of bolts and stones needed for the artillery engines. This required large quantities of iron and bronze, as well as the harvesting of animal hair/sinew from across the Levant.

8. Length, Religion, and Outcome: 7 Months of Fury ⏳

The conclusion of the siege was one of the bloodiest episodes of Alexander’s life, serving as a warning to the rest of the world.

- Duration: The siege lasted from January to July 332 BC.

- The Religious Sacrifice: After the city fell, Alexander finally marched to the Temple of Melqart. He performed the sacrifice he had been denied seven months earlier, dedicating the Tyrian sacred ship and the battering ram that broke the wall to the god.

- The Massacre: Enraged by the long resistance and the Tyrians’ execution of Macedonian prisoners on the walls, Alexander showed no mercy. 6,000 Tyrians were killed in the fighting, and 2,000 men were crucified along the shore.

- The End of an Era: 30,000 citizens were sold into slavery. The Persian navy ceased to exist as an effective force, and the way to Egypt—and ultimately to the heart of the Persian Empire—was now wide open.

- Geographical Legacy: Alexander’s mole was so massive that sand accumulated against it over centuries. Today, Tyre is no longer an island; it is a peninsula, a permanent monument to Alexander’s engineering will.

Would you like me to…

- Explain the internal mechanics of the torsion catapults Alexander used?

- Compare the siege of Tyre to the Roman siege of Carthage?

- Focus on the archaeological findings of the mole in modern-day Lebanon?

🌊 The Siege of Tyre Legacy

Tyre view from an airplane, 1934

(Wiki Image By work for the French government – Published in an academic French book “UN GRAND PORT DISPARU T Y R” in 1939, loaded from: almashriq.hiof.no/general/900/930/933/tyr-poidebard/tyr.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1165307)

The legacy of the Siege of Tyre (332 BC) is unique because it is one of the few military engagements in history that resulted in a permanent change to the earth’s geography. Alexander the Great did not just defeat a city; he fundamentally altered the Mediterranean coastline.

Beyond the physical changes, the siege set new standards for military engineering, psychological warfare, and the strategic use of naval power.

🌍 1. Geographical Legacy: The Tombolo

The most enduring legacy is the Mole. Alexander’s engineers dumped millions of tons of rock and earth into the 800-meter channel separating the island from the mainland.

- Siltation: Because the mole blocked the natural north-to-south currents, sand and silt accumulated against the structure over the centuries.

- The Peninsula: This process, known as tombolo formation, eventually widened the land bridge. Today, the ancient island of Tyre is a permanent peninsula, and the modern city of Sour (Lebanon) sits directly atop the footprint of Alexander’s engineering project.

🏗️ 2. Engineering and Artillery Standards

The siege served as the “laboratory” for Hellenistic military technology. Many of the techniques developed here became the gold standard for the next 300 years.

- Torsion Power: The heavy use of torsion catapults (using twisted animal sinew) proved that stone walls were no longer invincible. This led to a “defense arms race,” in which cities began building much thicker, multilayered walls to withstand heavier projectiles.

- The Mobile Tower: The 150-foot siege towers built by Diades of Pella remained the most significant mobile structures ever built until the Roman era. They inspired the later Helepolis (“City-Taker”) used at the Siege of Rhodes.

⚓ 3. The Birth of Combined Arms Naval Warfare

Before Tyre, naval battles mainly were about ramming and boarding at sea. Alexander changed the role of the navy forever by integrating it into land-based siege tactics.

- The Naval Battery: By lashing ships together to create stable catamarans, Alexander invented the concept of the floating artillery platform. This allowed him to bring the power of a land-based siege engine to the weakest parts of a city’s defenses—the sea walls.

- Harbor Control: The systematic blockade of the Sidonian and Egyptian harbors at Tyre served as a blueprint for naval blockades employed throughout the Roman and Byzantine periods.

🏛️ 4. Political and Psychological Legacy

The fate of Tyre served as a terrifying “object lesson” for the rest of the ancient world.

- The Message of Gaza and Egypt: When Alexander moved south to besiege Gaza and then into Egypt, the memory of Tyre’s destruction ensured that resistance was minimal. The total enslavement of the population and the crucifixions along the shore were calculated acts of terror-as-strategy.

- The End of Phoenician Dominance: Tyre had been the premier maritime power of the Mediterranean for centuries. Its fall signaled the end of Phoenician independence and the beginning of the “Hellenization” of the Levant, in which Greek culture and language became the dominant forces.

🔍 5. Archaeological Legacy

Today, the remains of the siege provide a wealth of information for marine archaeologists.

- Submerged Structures: Underwater excavations have revealed the foundations of the mole and the massive boulders that Alexander’s “crane ships” winched aside.

- Weaponry Finds: Divers have discovered lead sling bullets, bronze arrowheads, and stone catapult balls in the harbors, offering a physical record of the “multi-directional” assault Alexander launched on the final day.

Would you like me to…

- Provide a technical comparison between the walls of Tyre and the later walls of Constantinople?

- Analyze the economic impact of losing Tyre on the Persian Empire’s war effort.

- Explore the legend of Alexander’s diving bell, which some accounts claim he used during this siege.

🌊 The Siege of Tyre (332 BC) YouTube Links Views

The Siege of Tyre (332 BC) is one of Alexander the Great’s most legendary accomplishments, often featured on YouTube for its unique blend of engineering and naval warfare.

🎥 Top-Rated & High-View Documentaries

- BazBattles: The Siege of Tyre 332 BC

- Views: ~1.6M+

- Style: The definitive visual guide for this siege. It uses a clean, minimalist animation style to show the construction of the mole, the Tyrian fire ship attack, and the final naval breakthrough.

- Kings and Generals: Siege of Tyre 332 BC – Alexander the Great DOCUMENTARY (Note: Often part of their “Alexander” playlist)

- Style: Known for cinematic map transitions and deep dives into the political stakes of the Phoenician coast. This video explains why Alexander had to take Tyre before moving to Egypt.

- IRON LEGACY: 332 B.C. The Siege of Tire and the Wrath of Alexander the Great

- Views: ~1.8K+

- Style: A newer narrative-driven account that focuses on the “wrath” of Alexander and the brutal aftermath of the seven-month investment.

🏛️ Engineering & Strategic Highlights

- Great Military Feats: Alexander The Great Greatest Victory: The Siege Of Tyre

- Views: ~2.4K+

- Style: Focuses on the “impossible” nature of the conquest, specifically the construction of the 800-meter mole that turned an island into a peninsula.

- Mysteries of the Past: The Impossible Conquest

- Style: A short, impactful summary of the technological innovations, such as the 150-foot siege towers and ship-mounted battering rams.

📊 Summary

- For Tactical Map Animation: Watch BazBattles.

- For Historical Context & “Big Picture”: Watch Kings and Generals.

For Engineering Focus: Great Military Feats provides a solid overview of the mole construction.

🌊 The Siege of Tyre Books

The Siege of Tyre is rarely the sole subject of a popular history book, as it is part of the larger Persian campaign. However, several specialized military histories dedicate significant chapters to the engineering and tactics of this specific battle.

Here are the top book recommendations for understanding the Siege of Tyre, categorized by their focus.

- The Definitive Military Analysis

“The Sieges of Alexander the Great” by Stephen English

- Focus: Military Engineering & Siegecraft.

- Why read it: Unlike general biographies that gloss over the mechanics, this book focuses exclusively on how Alexander took cities. It devotes a substantial section to Tyre, detailing the construction of the mole, the torsion artillery, and the countermeasures used by the Tyrians (such as heated sand and divers). It is the best resource for the specific technical details you are interested in.

- The Strategic Masterclass

“The Generalship of Alexander the Great” by J.F.C. Fuller

- Focus: Strategy & Tactics.

- Why read it: J.F.C. Fuller was a British Major General and a pioneer of armored warfare. He analyzes Alexander not as a “king” or “hero,” but as a professional general. His breakdown of the “Grand Strategy” of the Tyre campaign—explaining the “Dry Land” naval strategy and why the siege was a strategic necessity rather than an ego trip—is considered the gold standard in military academies.

- The Logistics “Why”

“Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army” by Donald W. Engels

- Focus: Logistics & Supply Lines.

- Why read it: You were interested in why Alexander stopped to take Tyre. This book mathematically proves why he had to. Engels calculates the army’s calorie needs, water requirements, and march rates to show that Alexander could not march to Egypt while Tyre remained hostile in his rear. It turns the siege from a battle story into a fascinating study of survival and supply chains.

- The Primary Source (Eyewitness Account)

“The Campaigns of Alexander” (Anabasis Alexandri) by Arrian

- Focus: First-hand History.

- Why read it: This is the text all modern historians use. Arrian drew from the journals of Ptolemy (Alexander’s general), who was physically present at the siege. If you want to read the original description of the monsters of the deep attacking the workers on the mole, or the exact moment the wall was breached, this is the source.

- The Visual Guide

“Alexander the Great at War” by Ruth Sheppard (Osprey Publishing)

- Focus: Visuals, Maps & Equipment.

- Why read it: Osprey books are famous for their illustrations. This volume contains excellent tactical maps of the siege of Tyre, showing the progression of the mole and the naval blockade. It also features detailed illustrations of the siege towers (Helepolis) and the artillery used, helping you visualize the “Impossible Island.”

🔧 The Siege of Syracuse (213–212 BC)

🔧 Archimedes

The defense of Syracuse was masterminded by the polymath Archimedes, whose engineering genius transformed the city into an impregnable fortress against the Roman siege train. He devised terrifying counter-measures for the Roman fleet, most notably the “Claw of Archimedes”—a massive crane-operated hook that could descend from the walls, hoist enemy galleys by their prows, and capsize them into the sea. Furthermore, when the Romans deployed their Sambuca (floating siege towers mounted on paired ships) to scale the seawalls, Archimedes effectively neutralized them with hidden artillery and heavy stones that disabled the delicate mechanisms before they could breach the fortifications, demonstrating that superior intellect could hold an entire army at bay.

Claw of Archimedes (shown above) and the Sambuca (shown below) (Wikipedia Image)

According to Plutarch:

“A ship was frequently lifted to a great height [by the Claw] in the air (a dreadful thing to behold) and was rolled to and fro, and kept swinging until the mariners were thrown out when at length it was dashed against the rocks, or let fall. At the engine that [Proconsul] Marcellus brought upon the bridge of the ship, called a Sambuca, from some resemblance it had to an instrument of music, while it was yet approaching the wall, there was discharged a piece of rock of ten talents weight [710 pounds] than a second and a third, which, striking upon it with immense force and a noise like thunder, broke all its foundation to pieces, shook out all its fastings, and completely dislodged it from the bridge.”

🔧 The Siege of Syracuse Quotes

The Siege of Syracuse (213–212 BC) is primarily documented by the historians Polybius, Livy, and Plutarch. Their accounts focus heavily on the tension between Roman industrial military power and the singular, terrifying genius of Archimedes.

Here are the most significant quotations regarding the siege, categorized by the technologies and tactics employed.

⚙️ The Genius of Archimedes

Historians often described Archimedes not as a mathematician but as a “geometric Briareus” (a hundred-armed giant) who fought the Roman army single-handedly.

“Archimedes had so designed his artillery that it could be used against an enemy at any distance… as they [the Romans] fell into his range, he hit them with stones and bolts of every size.” — Polybius, The Histories

“He [Archimedes] did not think these inventions were worth any serious study, but considered them as the mere recreation of a geometrician in his leisure.” — Plutarch, Life of Marcellus

⚓ The Failure of the Naval Assault

The Roman commander Marcellus attempted a grand naval landing using the “Sambuca,” only to be mocked by the results of Archimedes’ machines.

“Marcellus was in a state of great distress… for Archimedes used his ships to ladle out his wine, and his engines to treat the Sambucas with the greatest possible ignominy.” — Plutarch

“The Claw [of Archimedes] would suddenly lift a ship by the prow, stand it upright on its stern, and then plunge it back into the sea… to the great terror and destruction of the crews.” — Polybius

🏹 The Psychological Warfare

The Romans, usually a fearless and disciplined force, became so traumatized by the “miracles” of the city’s defense that they lost their nerve.

“The Romans were so terrified that if they only saw a piece of rope or a small baulk of wood protruding over the wall, they would cry out that Archimedes was turning some engine upon them, and they would turn and flee.” — Plutarch

“In a word, such is the power of a single intellect… the Romans, who were so many and so brave, were baffled by the genius of one man.” — Polybius

🏺 The Fall and the Death of Archimedes

The siege ended not through technology, but through stealth during a religious festival. The death of Archimedes remains one of the most famous tragedies in military history.

“Do not disturb my circles!” (Noli turbare circulos meos!) — Archimedes’ traditional final words to the Roman soldier.

“Marcellus was deeply grieved by his death… he gave the man a burial with all honor and treated his relatives with great kindness.” — Livy, History of Rome

🏛️ The Cultural Impact

Syracuse was a center of Hellenistic art, and its fall marked the beginning of Rome’s transformation into a cosmopolitan empire.

“From this time began the Romans’ admiration for Greek art, and the custom of plundering the cities of the world.” — Plutarch.

“The city was so beautiful and so filled with treasure that Marcellus is said to have wept when he looked down upon it from the heights, thinking of its approaching ruin.” — Livy

Would you like me to…

- Analyze the technical accuracy of Polybius’s descriptions of the catapults?

- Explain the “Festival of Artemis” breach and how the Romans used a religious holiday to their advantage?

- Detail the tomb of Archimedes and how Cicero rediscovered it centuries later?

🔧 The Siege of Syracuse (213–212 BC) Prehistory

The “prehistory” of the Siege of Syracuse (213–212 BC) is a geopolitical tragedy driven by the power vacuum created by the Second Punic War. It explains how a city that had been Rome’s most loyal ally for fifty years suddenly became its most dangerous enemy.

- The Golden Age of Hiero II (270–215 BC)

For half a century, Syracuse was ruled by King Hiero II. He was a brilliant pragmatist who recognized early on that Rome was the rising superpower of the Mediterranean.

- The Roman Alliance: Hiero signed a treaty with Rome in 263 BC. For decades, he provided Rome with grain, gold, and archers during its wars against Carthage.

- The Preparation: Despite the peace, Hiero was paranoid about the city’s safety. He commissioned his kinsman, the mathematician Archimedes, to upgrade the city’s defenses. The “super-weapons” used against the Romans were actually designed years earlier, intended to protect the city from Carthage.

- The Shock of Cannae (216 BC)

The catalyst for the war occurred on the Italian mainland. In 216 BC, Hannibal Barca annihilated the Roman army at the Battle of Cannae.

- The Perception of Weakness: To the Greeks in Sicily, Rome appeared finished. The invincible legion had been crushed. Pro-Carthaginian factions within Syracuse began to whisper that Hiero was backing the wrong horse.

- The Death of the King: In 215 BC, the aged Hiero II died, leaving the throne to his 15-year-old grandson, Hieronymus.

- The Boy King and the Flip

Hieronymus was young, vain, and easily manipulated by courtiers whom Hannibal had bribed.

- The Carthaginian Offer: Hannibal promised Hieronymus that, if he defected, Carthage would grant him sovereignty over all of Sicily once Rome was defeated.

- The Defection: Hieronymus openly mocked the Roman envoys and pledged Syracuse’s vast navy and resources to Carthage. This threatened to cut off Rome’s grain supply precisely when it was most vulnerable.

- The Republic of Chaos (214 BC)

Hieronymus’s reign was short; he was assassinated by a pro-Roman conspiracy after only 13 months. Syracuse briefly declared itself a Republic, but it descended into anarchy.

- Hippocrates and Epicydes: Two brothers—Syracusan Greeks by birth but agents of Hannibal—seized control of the military. They whipped the population into a frenzy, claiming Rome intended to enslave the city.

- The Massacre at Leontini: The brothers took their army to the neighboring city of Leontini and massacred the Roman garrison there. This was the point of no return.

- The Roman Hammer: Marcellus Arrives

Rome sent Marcus Claudius Marcellus, known as the “Sword of Rome,” to Sicily to restore order.

- The Retaliation: Marcellus stormed Leontini. Reports (likely exaggerated by Carthaginian propaganda) spread that he had massacred the civilians.

- The Gates Close: Upon hearing of the “Sack of Leontini,” the citizens of Syracuse panicked. They fully embraced Hippocrates and Epicydes, locked the city gates, and manned the walls.

- The Stage Set: Marcellus marched his legions to the walls of Syracuse, expecting a quick surrender. Instead, he found Archimedes waiting for him.

Summary Table: The Slide into War

| Year | Event | Strategic Impact |

| 263–215 BC | Reign of Hiero II | Syracuse is a stable, wealthy Roman ally; Archimedes fortifies its defenses. |

| 216 BC | Battle of Cannae | Rome loses 50,000 men to Hannibal; Roman prestige collapses. |

| 215 BC | Hieronymus takes the throne | Carthaginian promises seduce the new boy-king. |

| 214 BC | Assassination & Coup | Pro-Carthaginian agents seize control of the Syracusan army. |

| 213 BC | Arrival of Marcellus | Rome invades Sicily; the Siege of Syracuse begins. |

Would you like me to…

- Analyze the geography of Syracuse (Ortygia vs. Epipolae) that made it so defensible?

- Detail the specific defensive preparations Archimedes made during the peace of Hiero II?

Compare the leadership style of Hiero II vs. that of his disastrous grandson, Hieronymus.

🔧 The Siege of Syracuse Chronological Table

Ortygia Island, where Syracuse was founded in ancient Greek times

(Wiki Image By cc-by-2.0, Attribution, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23148161)

🔧 The Siege of Syracuse (213–212 BC): Chronological Table

Below is a clear, step-by-step chronological table outlining the primary phases, technologies, tactics, and turning points of the Roman siege of Syracuse during the Second Punic War.

🔧 Siege of Syracuse — Chronological Timeline

| Year / Phase | Event | Key Technology & Tactics | Strategic Significance |

| 214 BC | Syracuse switches allegiance to Carthage after the death of King Hiero II | Political realignment; fortified city | Forces Rome to neutralize a critical naval and grain hub |

| 214 BC | Roman army and fleet arrive under Marcus Claudius Marcellus | Combined land–sea siege | Rome expects a quick victory based on overwhelming force |

| 214 BC | Initial Roman naval assault fails | Archimedes’ defensive machines: stone-throwers, ballistae | Romans shocked by technological superiority |

| 214 BC | “The Claw of Archimedes” deployed | Crane-like grappling device lifts and capsizes ships | Roman fleet suffers heavy losses and retreats offshore |

| 214 BC | High-angle artillery counters Roman siege towers | Adjustable torsion catapults | Syracuse controls both long- and short-range engagements |

| 213 BC | Roman morale collapses | Psychological warfare via surprise mechanical defenses | Romans abandon direct assaults |

| 213 BC | Roman blockade begins | Starvation strategy replaces engineering assault | Siege shifts from technology to logistics |

| 213 BC | Roman winter encampment established | Sustained supply lines | Demonstrates Roman endurance advantage |

| 212 BC (Spring) | Plague and famine inside Syracuse | Disease spreads due to overcrowding | Weakens civilian resistance |

| 212 BC (Summer) | Festival of Artemis was celebrated | Reduced guard discipline | Creates a critical vulnerability |

| 212 BC | Roman night infiltration | Ladder assault during the festival | Romans breached the Epipolae plateau |

| 212 BC | City systematically captured | Street-by-street infantry combat | End of organized Syracusan resistance |

| 212 BC | Death of Archimedes | Killed by a Roman soldier | Loss of the greatest scientific mind of antiquity |

| 212 BC | Sack of Syracuse | Looting; deportation of citizens | Rome acquires vast Greek art and knowledge |

🔑 Key Siege Characteristics (At a Glance)

| Category | Syracuse |

| Length | ~2 years |

| Primary Defender Advantage | Advanced engineering & artillery |

| Primary Roman Advantage | Logistics, manpower, patience |

| Decisive Factor | Starvation + internal complacency |

| Historical Legacy | Triumph of endurance over genius |

🧠 Why Syracuse Matters

- First recorded “scientific war”: mathematics and physics were used systematically in defense.

- Turning point in Roman warfare: Romans learn to outlast technology

- Cultural catastrophe: loss of Archimedes and absorption of Greek science into Rome

If you’d like, I can also provide:

- 📊 a side-by-side comparison with Tyre, Alesia, or Masada

- 🧠 a deep dive into Archimedes’ machines

- ⚔️ a Roman vs Greek siege doctrine comparison

Just say the word.

🔧 The Siege of Syracuse History

Archimedes directing the defenses of Syracuse

(Wiki Image By Thomas Ralph Spence – www.artfinding.com/Biography/Spence-Thomas-Ralph, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30470075)

The Siege of Syracuse (213–212 BC) was a centerpiece of the Second Punic War, pitting the industrial military might of the Roman Republic against the scientific ingenuity of the Greek mathematician Archimedes.

The siege is legendary not just for its brutality, but for being perhaps the only time in history a single man’s intellect held an entire empire at bay for years.

🏛️ The Strategic Context: A Broken Alliance

For fifty years, Syracuse had been a loyal Roman ally under King Hiero II. However, after the Roman disaster at the Battle of Cannae, the pro-Carthaginian faction in Syracuse gained control. The young new king, Hieronymus, defected to Hannibal, threatening the Roman grain supply in Sicily. Rome responded by sending the veteran consul, Marcus Claudius Marcellus, to recapture the city.

⚓ Phase I: The Failed Naval Assault

Marcellus arrived with a fleet of 60 quinqueremes, confident that a direct sea assault would break the city. He deployed the Sambuca, a massive scaling ladder mounted on pairs of lashed-together ships.

However, the Romans were met with the “Super-Weapons” of Archimedes:

- The Claw of Archimedes: Giant crane-like arms equipped with grappling hooks that snagged Roman ships, lifted them out of the water, and dropped them to their destruction.

- Variable-Range Torsion Engines: Catapults and “Scorpions” (bolt-throwers) that fired with such precision that they cleared the Roman decks from hundreds of yards away, as well as at point-blank range through hidden “loopholes” in the walls.

🧱 Phase II: The Euryalus Fortress and Land War

Marcellus also attempted to storm the city by land via the Epipolae ridge. Here, the Romans encountered the Euryalus Fortress, the most sophisticated defensive work of the Greek world.

The fortress featured:

- Deep Dry Moats: Preventing the use of Roman battering rams or siege towers.

- Underground Tunnels: Allowing the defenders to move troops secretly to launch surprise counter-attacks on the Roman flanks before vanishing back into the earth.

🥖 Phase III: The Two-Year Blockade

Realizing that direct assault was suicide, Marcellus shifted to a blockade. For two years, the Roman army surrounded the city, attempting to starve the population.

- Logistical Strain: The Romans had to fend off Carthaginian relief fleets and armies while maintaining their own camps in the swampy, malaria-ridden lowlands south of the city.

- The “Marsh Fever”: A plague broke out in the Carthaginian relief camp in the Lysimachia marshes, killing their commanders and thousands of soldiers. At the same time, the Romans on higher ground remained relatively healthy.

🏹 The Fall: Stealth and Betrayal

The city did not fall to a machine, but to a lapse in security. In 212 BC, Marcellus noticed a low, unguarded section of the wall near the Trogilus gate.

- The Festival of Artemis: While the Syracusans were celebrating a religious festival with heavy wine, a small party of Roman soldiers scaled the walls in the dark.

- The Breach: They opened the gates from the inside, allowing the Roman army to flood the outer districts (Tyche and Neapolis).

- The Final Traitor: The inner island of Ortygia held out for a few more months until a Spanish mercenary officer betrayed the city and opened the final gates to the Romans.

⚖️ The Aftermath and the Death of Archimedes

The sack of Syracuse was famously brutal. Despite Marcellus giving strict orders to spare Archimedes, a Roman soldier found the 75-year-old mathematician drawing geometric diagrams in the dirt. When Archimedes reportedly told the soldier, “Do not disturb my circles,” the soldier killed him.

The legacy of the siege was two-fold:

- Political: It solidified Roman control over Sicily, which would remain a Roman province for centuries.

- Cultural: The massive amount of Greek art and scientific instruments looted from Syracuse and sent to Rome sparked the “Hellenization” of Roman culture, forever changing the Republic’s intellectual trajectory.

Would you like me to…

- Provide a technical breakdown of the physics behind the Claw of Archimedes?

- Detail the archaeological remains of the Euryalus Fortress today?

- Compare this siege to the Roman Siege of Jerusalem in 70 AD?

🔧 The Siege of Syracuse (213–212 BC): 8 top essential aspects, including technology, engineering, tactics, strategy, artillery, infantry, cavalry, navy, plague, religion, logistics, walls, manpower, and length.

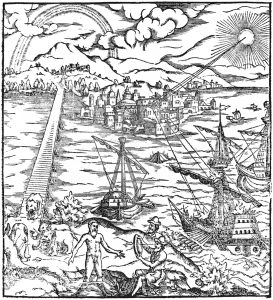

Archimedes set Roman ships on fire before Syracuse with the help of parabolic mirrors.

(Wiki Image By Unknown illustrator – Bavarian State Library, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=503708)

The Siege of Syracuse (213–212 BC) stands as one of the most intellectually and technologically sophisticated conflicts of the ancient world. It was a collision between the burgeoning industrial military might of the Roman Republic and the peak of Hellenistic scientific achievement, embodied by the polymath Archimedes.

To provide a comprehensive analysis, we will break the siege down into eight essential pillars: the defensive genius of Archimedes, the Roman naval innovations, the formidable engineering of the city walls, the grand strategy of the Second Punic War, the tactical stealth that led to the breach, the biological impact of the plague, the logistical nightmare of the blockade, and the tragic cultural outcome.

1. Technology: The “Machines of Archimedes” ⚙️

The defense of Syracuse was not a feat of manpower, but of mathematics. Archimedes turned the city’s fortifications into an automated killing machine that nearly broke Roman morale.

- The Claw of Archimedes: This was a giant, crane-like machine positioned behind the seawalls. When a Roman ship approached, the Claw would swing out, lower a grappling hook, snag the ship’s prow, and lift it vertically. Once the ship was suspended, the Claw would release it, causing the vessel to capsize or smash against the rocks. This neutralized the Roman naval advantage entirely.

- Variable-Range Torsion Engines: Archimedes revolutionized artillery by creating catapults and ballistae with adjustable ranges. Most ancient artillery had a “blind spot” near the wall; Archimedes created “scorpions” (small, high-velocity bolt throwers) that fired through narrow apertures in the masonry, striking Romans who believed they were safe at the base of the wall.

- The Burning Mirrors (Debated): While historically controversial, legend states Archimedes used parabolic bronze mirrors to focus sunlight onto Roman sails, igniting them. Whether true or a later embellishment, it reflects the Roman perception that Syracuse was defended by “miracles.”

- Mechanical Synergy: The technology was integrated into the architecture. The walls weren’t just stone; they were platforms for gears, pulleys, and winches that amplified the defenders’ force.

2. Engineering: The Walls of Dionysius 🧱

Syracuse was protected by one of the most sophisticated defensive systems in history, constructed over generations and perfected by the tyrant Dionysius I and later Hiero II.

- The Euryalus Fortress: Located at the western tip of the Epipolae ridge, this was the strongest fort in the Greek world. It featured three massive dry moats, complex gate systems designed to trap attackers in “kill zones,” and five massive towers that could house giant catapults.

- Subterranean Warfare: The fortress was connected to the city by an extensive network of underground tunnels. These allowed the defenders to move troops, supplies, and even small engines secretly across miles of territory, launching surprise sorties behind Roman lines and then vanishing back into the earth.

- Aperture Engineering: The sea-facing walls were modified with “loopholes”—small, funnel-shaped openings. These allowed archers to fire with a wide field of view while remaining almost entirely invulnerable to incoming Roman arrows.

3. Navy: The Roman Sambuca ⚓

The Roman commander, Marcus Claudius Marcellus, realized he could not take the city by land, so he attempted a massive naval assault using a new Roman engineering device: the Sambuca.

- Structure: The Sambuca (named after a triangular harp) was a massive scaling ladder mounted on two quinqueremes (galleys) lashed together. The ladder was enclosed in a protective wooden shed to shield the boarding party.

- The Counter-Measure: As the Sambucas approached, Archimedes used heavy catapults to launch stones weighing over 600 pounds. These massive projectiles smashed through the wooden roofs of the Sambucas and the decks of the ships below, sinking them before they could reach the walls.

- Psychological Impact: The failure of the Sambuca convinced the Romans that Syracuse was impregnable by sea. Marcellus famously joked that Archimedes was using his ships as “ladles to draw out his wine.”

4. Strategy: The Second Punic War Context 🌍

The siege was not an isolated event; it was a pivot point in the struggle between Rome and Hannibal’s Carthage.

- The Betrayal: Syracuse had been a Roman ally for 50 years under King Hiero II. Upon his death, his grandson Hieronymus switched sides to Carthage, threatening the Roman grain supply and their control over the Mediterranean.

- The Mediterranean “Chessboard”: Rome could not afford a Carthaginian stronghold in Sicily. If Syracuse held out, Carthage could use it as a base to ferry reinforcements to Hannibal, who was then ravaging the Italian mainland.

- Marcellus’s Mandate: Marcellus was given a “total war” mandate. He had to capture Syracuse at any cost to prevent the collapse of the Roman western front. This led to the shift from a tactical assault to a two-year strategic blockade.

5. Tactics: The Breach at the Feast of Artemis 🏹

After 24 months of stalemate, the Romans finally entered the city through intelligence and stealth rather than brute force.

- The Weak Point: During a parley with a Syracusan diplomat, a Roman officer observed a section of the wall (near the Trogilus gate) that was slightly lower and less heavily guarded.

- Religious Timing: Marcellus learned that the city was about to celebrate a three-day festival in honor of the goddess Artemis. He gambled that the garrison would be preoccupied with religious ritual and wine.

- The Night Raid: A small elite party of 1,000 Roman soldiers scaled the wall in the dead of night. They moved through the Tyche and Neapolis districts, killing the drunken guards and opening the gates for the main army. By dawn, the outer city had fallen.

6. Plague: The “Invisible” Defender 🤒

Just as it seemed the Romans would complete their conquest, a Carthaginian relief army arrived, leading to a biological catastrophe that determined the city’s fate.

- The Lysimeleia Marshes: The Carthaginian army, led by Himilco, camped in the low-lying, humid marshes south of the city. This was a breeding ground for disease (likely malaria or typhus).

- The Outbreak: In the summer heat of 212 BC, a devastating plague broke out. The Carthaginian and Syracusan relief forces were decimated, with Himilco and the Syracusan commander Hippocrates both dying from the infection.

- The Roman Advantage: The Romans, stationed on the higher, drier ground of the Epipolae ridge, suffered far fewer casualties. This plague removed the last hope of outside rescue for the besieged Syracusans.

7. Logistics: The Long Investment 🥖

A two-year siege requires an incredible amount of logistical planning for both the attacker and the defender.

- Supply Lines: The Romans had to maintain a fleet of 100 quinqueremes and a land force of 25,000–30,000 men. They relied on grain from eastern Sicily and Italy, which was constantly threatened by the Carthaginian navy.

- Internal Starvation: Inside the city, the blockade eventually did what the machines could not. As Carthaginian supply ships were intercepted, the citizens of Syracuse began to starve. This led to internal discord and, eventually, to the betrayal of the inner island of Ortygia by a Spanish mercenary officer named Mericus to the Romans.

- Roman Persistence: The Roman “logistics of will” was their greatest strength. Despite being defeated by Archimedes’ machines and the Carthaginian navy, they refused to lift the siege until the city fell.

8. Outcome: The Death of a Genius 🏛️

The siege ended in a brutal sack that marked the end of the Hellenistic Golden Age and the start of Roman cultural dominance.

- The Order: Marcellus, a lover of Greek culture, had specifically ordered his troops to spare Archimedes, hoping to bring the scientist back to Rome.

- The Conflict: During the chaos of the sack, a Roman soldier encountered an old man drawing geometric diagrams in the dirt. Archimedes, supposedly annoyed by the interruption, told the soldier, “Do not disturb my circles.”

- The Death: The soldier, insulted and not recognizing the man, killed Archimedes on the spot. Marcellus was reportedly devastated and gave Archimedes a burial with full honors, but the greatest mind of the age was gone.

- The Loot: Syracuse was stripped of its treasures. Statues, paintings, and scientific instruments were sent to Rome, marking the first significant influx of Greek art into the Republic and fundamentally changing Roman taste and education.

Would you like me to…

- Compare the mechanics of Archimedes’ Claw with modern crane engineering?

- Provide a map-based breakdown of the various districts of Syracuse (Ortygia, Tyche, Achradina)?

- Explore the political career of Marcellus after his victory at Syracuse.

🔧 The Siege of Syracuse Legacy

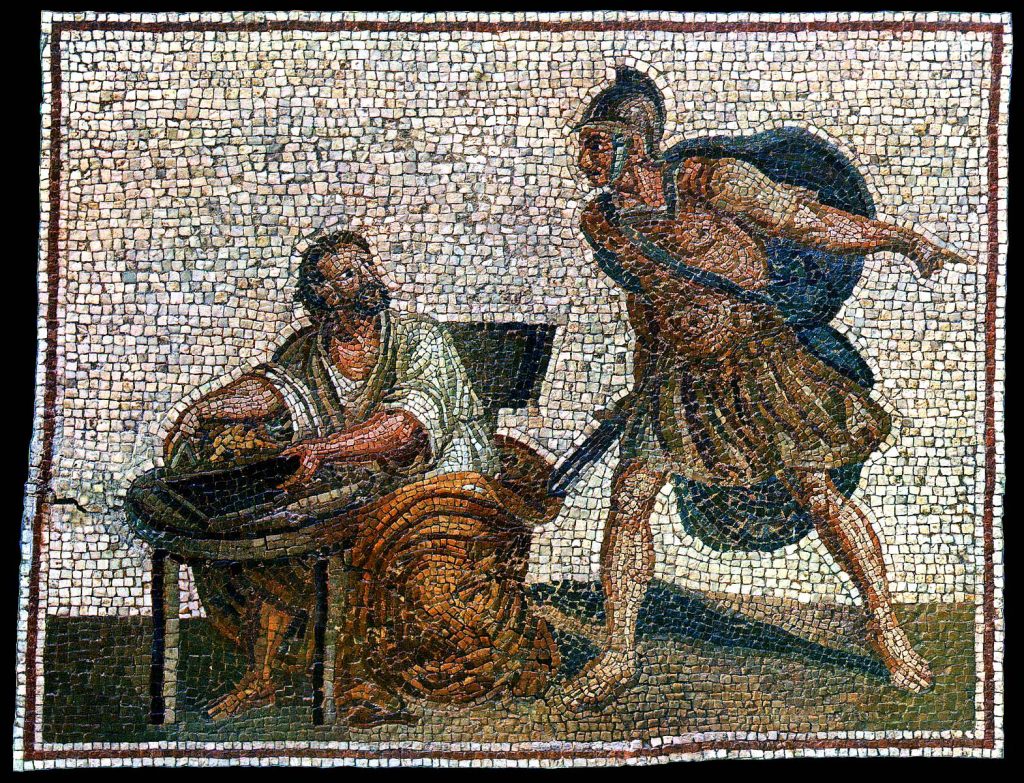

Archimedes, before his death, with a Roman soldier, a copy of a Roman mosaic from the 2nd century.

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – Scanned by Szilas from the book J. M. Roberts: Kelet-Ázsia és a klasszikus Görögország (East Asia and Classical Greece), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=52151843)

The legacy of the Siege of Syracuse (213–212 BC) extends far beyond a simple Roman victory in the Second Punic War. It represents a watershed moment in the history of science, the evolution of military engineering, and the cultural transformation of the Roman Republic itself.

Here are the 8 essential aspects of the siege’s enduring legacy:

- The Birth of “Genius” in Military History 🧠

Before Syracuse, battles were generally viewed as contests of manpower, bravery, or generalship. Syracuse introduced the concept of the scientist-as-warrior.

- Individual Impact: The siege proved that a single mind, using mathematics and physics, could neutralize the industrial might of a superpower.

- The “Archimedes Legend”: The accounts of his “super-weapons” created a template for the “mad scientist” or “defense contractor” that persists in Western literature and history to this day.

- Engineering: The Perfection of Defensive Architecture 🧱

The Euryalus Fortress remains one of the best-preserved examples of high Hellenistic military engineering.

- The Blueprint for Defense: Its use of complex dry moats, underground troop galleries, and tiered catapult batteries influenced later Roman and Byzantine fortification designs.

- Subterranean Warfare: The tunnels at Syracuse demonstrated the strategic value of “hidden” mobility, a concept later utilized in medieval castle design and modern trench warfare.

- The Industrialization of Siege Engines ⚙️

While Archimedes provided the “custom” genius, the Romans learned the value of standardized siege equipment.

- The Roman Response: Having been battered by Syracuse’s superior artillery, Rome accelerated its own development of the Ballista and Onager.

- Standardization: The failure of the Sambuca (the naval scaling ladder) led Roman engineers to refine amphibious landing craft and mobile boarding bridges that would eventually be used across the Mediterranean.

- Cultural Legacy: The “Grecianization” of Rome 🏺

The sack of Syracuse was the moment the Roman Republic “fell in love” with Greek culture—often called the Predatory Enlightenment.

- Art as Loot: Marcus Claudius Marcellus sent hundreds of statues, paintings, and scientific instruments from Syracuse to Rome.

- The Shift in Taste: The mass influx of Hellenistic art transformed Roman aesthetic tastes, leading to Horace’s famous quote: “Captive Greece took captive her savage conqueror.”

- Mathematics: The Preservation of the “Method” 📏

Despite his death at the hands of a Roman soldier, Archimedes’ works were mainly preserved because of the fame he gained during the siege.

- The Archimedes Palimpsest: His treatises on the sphere and cylinder, and his “Method of Mechanical Theorems,” were saved and studied by later Roman and Islamic scholars.

- The Tomb: Centuries later, the Roman statesman Cicero used his knowledge of the siege to locate Archimedes’ lost tomb (marked by a sphere and cylinder), proving that the scientist’s intellectual legacy outlived the city’s political power.

- Naval Tactics: The “Floating Battery” Concept ⚓

The siege pushed naval warfare beyond simple ramming and boarding.

- Stable Platforms: The Roman attempt to lash quinqueremes together to support heavy engines was a precursor to the modern monitor or battleship.

- Harbor Defense: Archimedes’ use of the “Claw” and sea-wall loopholes taught future empires that a harbor could be defended without a fleet, provided the shore-based artillery was sufficiently advanced.

- Strategic Logistics: The Importance of Sicily 🗺️

The fall of Syracuse effectively ended Carthaginian hopes of using Sicily as a “bridge” to Italy.

- Rome’s Breadbasket: With Syracuse back under Roman control, the Republic secured the grain supplies necessary to fuel its ultimate counter-offensive against Hannibal in Africa.

- Provincial Model: Sicily became Rome’s first province, and the administrative lessons learned there (taxation, grain quotas) set the standard for the entire Roman Empire.

- The Tragic Legend: Ethics in War ⚖️

The death of Archimedes remains a primary historical example of the “collateral damage” of war.

- The “Scholarly Martyr”: Archimedes is often portrayed as the first martyr of science—a man so focused on universal truths (his “circles”) that the mundane violence of political conquest destroyed him.

- Marcellus’s Regret: The fact that the Roman commander Marcellus mourned Archimedes’ death served as an early (if hypocritical) example of the “Laws of War” and the idea that some cultural assets should be spared from the sword.

Would you like me to…

- Analyze the physics of the “Death Ray” to see if Archimedes could have actually burned the Roman fleet?

- Detail the exact mechanisms of the Roman Ballista developed after this siege?

- Explore the modern ruins of Syracuse to see what remains of the 3rd-century BC walls.

🔧 The Siege of Syracuse (213–212 BC) YouTube Links Views

The Siege of Syracuse (213–212 BC) is one of the most famous sieges in ancient history, largely due to the legendary genius of Archimedes and his war machines. On YouTube, this topic is often covered by military history and ancient technology channels.

🎥 Top Documentary & Narrative Overviews

- Modern Historians: How One Genius Humiliated The Roman Republic: Siege of Syracuse (212 BC)

- Views: ~51K+

- Style: A deep-dive documentary (36 minutes) that focuses on the clash between Roman military persistence and the scientific ingenuity of Archimedes. It covers the political betrayal that ultimately led to the city’s fall.

- HistoryMarche: Siege of Syracuse, 213-212 BC – Hannibal (Part 21)

- Views: ~284K+

- Style: Part of a broader series on the Second Punic War. This video uses highly detailed 3D animated maps to explain the tactical movement of the Roman fleet under Marcellus and the layout of the city’s formidable defenses.

- Invicta: Punic-Sicilian Wars ⚔️ The Siege of Syracuse (397 BC)

- Views: ~192K+

- Note: While this focuses on an earlier siege, it provides essential context on why Syracuse was historically considered one of the most impregnable fortresses in the Mediterranean.

⚙️ Science & Inventions (The War Machines)

- Ancient Tech Files: Archimedes’ Death Ray

- Style: A short, technical look at the legend of the “heat ray”—mirrors used to set Roman ships on fire—and the archaeological/scientific debates surrounding it.

- The Claw of Archimedes: Many historical engineering channels feature recreations of the “Claw,” a giant crane mechanism that allegedly lifted Roman galleys out of the water and dropped them to their destruction.

🎬 Pop Culture Connections

- Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny: Meeting Archimedes (4K)

- Views: ~214K+

- Style: An excerpt from the 2023 film, which dramatizes a time-travel meeting during the actual 212 BC siege, bringing a renewed interest to the historical event.

📊 Summary

- For detailed tactical mapping, consult HistoryMarche.

- For Narrative & Historical Impact: Watch Modern Historians.

- For Ancient Engineering: Search for videos specifically on the Claw of Archimedes.

Would you like to find more information on the specific war machines Archimedes used, or perhaps a map of the city’s ancient fortifications?

🔧 The Siege of Syracuse Books

The Siege of Syracuse is often overshadowed by the larger conflict of the Second Punic War (Hannibal vs. Rome). Therefore, the most reliable information is found in books that focus on the war in Sicily or in biographies of the key players (Marcellus and Archimedes).

Here are the top book recommendations for the Siege of Syracuse.

- The Best Narrative History

“The Ghosts of Cannae: Hannibal and the Darkest Hour of the Roman Republic” by Robert L. O’Connell

- Focus: The Infantry & Manpower.

- Why read it: This is crucial for understanding the “Men” aspect of your request. The Roman legions besieging Syracuse were not regular troops; they were the “Ghosts”—the disgraced survivors of the Battle of Cannae. They had been banished to Sicily as punishment for losing to Hannibal. O’Connell explains how the Siege of Syracuse was their desperate bid for redemption, adding a powerful human element to the battle.

- The Definitive Military History

“The Fall of Carthage” (also published as “The Punic Wars”) by Adrian Goldsworthy

- Focus: Strategy & Tactics.

- Why read it: Goldsworthy is one of the top Roman military historians. His chapter on the Sicilian campaign is the best modern breakdown of the military situation. He analyzes Marcellus’s strategy, explaining why the Romans shifted from assault to blockade and how they handled the Carthaginian relief army (and the plague).

- The Engineering & Technology Source

“Archimedes” by E.J. Dijksterhuis

- Focus: Technology & Science.

- Why read it: If you want to understand the “Claw” and the catapults from a mathematical and engineering perspective, this is the classic scientific biography. It examines the mechanics of Archimedes’ inventions and his application of theoretical mathematics to physical warfare.

- The Primary Source (Where the myths come from)

“Life of Marcellus” (from Parallel Lives) by Plutarch

- Focus: Eyewitness-style Accounts.

- Why read it: This is the original source for almost every famous story about the siege. If you want to read the description of the Iron Hand lifting ships out of the water, or the account of Archimedes’ death (“Do not disturb my circles”), this is the text. It depicts the Roman terror of confronting “invisible” technological weapons vividly.

- The Regional Context

“Sicily: Three Thousand Years of Human History” by Sandra Benjamin

- Focus: Geopolitics & Walls.

- Why read it: Syracuse was the “New York City” of the ancient Mediterranean—wealthy, massive, and heavily fortified. This book provides the context for the city’s importance, detailing the construction of the gigantic Dionysian Walls and the Castle of Euryalus, which held the Romans at bay for two years.

Summary for your specific interests:

- For the “Men” (Infantry): Read The Ghosts of Cannae.

- For the “Machines” (Artillery): Read Archimedes or Plutarch.

- For the “Strategy”: Read The Fall of Carthage.

🌀 The Siege of Alesia (52 BC)

The fortifications built by Caesar in Alesia. Inset: a cross shows the location of Alesia in Gaul (modern France). The circle indicates a weakness in the northwestern section of the fortifications.

(Wiki Image By Muriel Gottrop at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 1.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20851)

🌀 The Siege of Alesia Quotes

The Siege of Alesia (52 BC) is primarily documented by Julius Caesar himself in his Commentaries on the Gallic War (De Bello Gallico), with additional perspective provided later by Plutarch and Cassius Dio. These quotes capture the cold, clinical engineering of the Romans and the desperate, emotional defiance of the Gauls.

🏛️ Caesar’s Engineering Resolve

Caesar describes his massive fortifications with the detachment of an architect, highlighting the “Death Fields” he created to protect his legions.