Lincoln, Theodore Judah, Leland Stanford, and Grenville Dodge: Transcontinental Railroad

1863–1869: Union Pacific built west (blue line), Central Pacific built east (red), and Western Pacific built the last leg (green)

(Wiki Image By Cave cattum – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=783429)

While thousands labored to build the Transcontinental Railroad, its completion hinged on the distinct and crucial contributions of four men: Abraham Lincoln, the political visionary; Theodore Judah, the engineering dreamer; Leland Stanford, the corporate financier; and Grenville Dodge, the master of construction.

Abraham Lincoln: The Political Visionary

As a young lawyer in Illinois, Abraham Lincoln was a staunch advocate for a railroad connecting the East and West coasts. He saw it as a vital tool for unifying the nation and promoting economic growth. During the Civil War, he recognized its immense strategic importance for binding California and the West to the Union.

- Key Contribution: In the midst of the Civil War, Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act of 1862. This act was the most critical step in the railroad’s creation. It authorized the creation of two companies, the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific. It provided them with enormous government support in the form of land grants and financial bonds for every mile of track they laid. Without Lincoln’s signature and unwavering support, the project would never have begun.

Theodore Judah: The Engineering Dreamer

Theodore Judah was a brilliant civil engineer with an obsessive, all-consuming vision: to find a viable route for a railroad through the seemingly impassable Sierra Nevada mountains. He surveyed the mountains tirelessly and, against all odds, found a gradual, buildable path over Donner Pass.

- Key Contribution: Judah was the “Father of the Central Pacific Railroad.” He not only engineered the route but also created the business and political plan. He tirelessly lobbied Congress in Washington, D.C. to support the Pacific Railway Act. He was also the one who brought together the four Sacramento merchants, including Leland Stanford, who would later become known as the “Big Four” and finance the project. Tragically, Judah died of yellow fever in 1863, before he could see his dream fully realized.

Leland Stanford: The Corporate Financier

Leland Stanford was a wealthy Sacramento merchant and the Governor of California. He was one of the “Big Four,” the primary investors who formed the Central Pacific Railroad Company under the guidance of Leland Stanford. While his partners managed the day-to-day operations, Stanford’s political power and financial leadership were essential.

- Key Contribution: As president of the Central Pacific, Stanford leveraged his political connections as governor to secure state funding and favorable legislation. He was the corporate face of the western half of the railroad, and he famously drove the “Last Spike” (the Golden Spike) at Promontory Summit, Utah, in 1869, officially completing the line.

Grenville Dodge: The Master of Construction

A former Union Army general, Grenville Dodge was the chief engineer for the Union Pacific Railroad, the company building westward from Omaha, Nebraska. Dodge was a brilliant and ruthless project manager, ideally suited to the immense logistical and physical challenges of building across the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains.

- Key Contribution: Dodge organized and managed a massive, disciplined workforce composed mainly of Irish immigrants and Civil War veterans. He planned the route, fought off raids from Native American tribes who were defending their land, and pushed his crews to lay track at a relentless, record-breaking pace. His operational genius was the driving force that completed the Union Pacific’s half of the monumental project.

| Name | Role / Contribution | Significance |

| Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865) | As President, he signed the Pacific Railway Act (1862), which authorized construction of the Transcontinental Railroad. | Saw the railroad as a way to bind the Union together during the Civil War, strengthen federal authority, and promote westward expansion. His political backing made the project possible. |

| Theodore Judah (1826–1863) | Chief engineer and visionary behind the Central Pacific Railroad; surveyed the Sierra Nevada and pushed Congress for funding. | Known as the “Father of the Transcontinental Railroad.” Without his technical vision and lobbying, the project might not have begun and would have died young (at age 37) before being completed. |

| Leland Stanford (1824–1893) | One of the “Big Four” investors of the Central Pacific Railroad (with Crocker, Huntington, Hopkins). Later drove the golden spike at Promontory Summit (1869). | Provided financing, political connections, and leadership. Became a railroad tycoon, California governor, U.S. senator, and founder of Stanford University. |

| Grenville Dodge (1831–1916) | Chief engineer of the Union Pacific Railroad. Directed construction across the Great Plains and the Rockies. | Brilliant military engineer (Civil War veteran) who organized labor, managed logistics, and solved enormous engineering challenges. His leadership made the eastern half possible. |

Economic Impacts of the Transcontinental Railroad

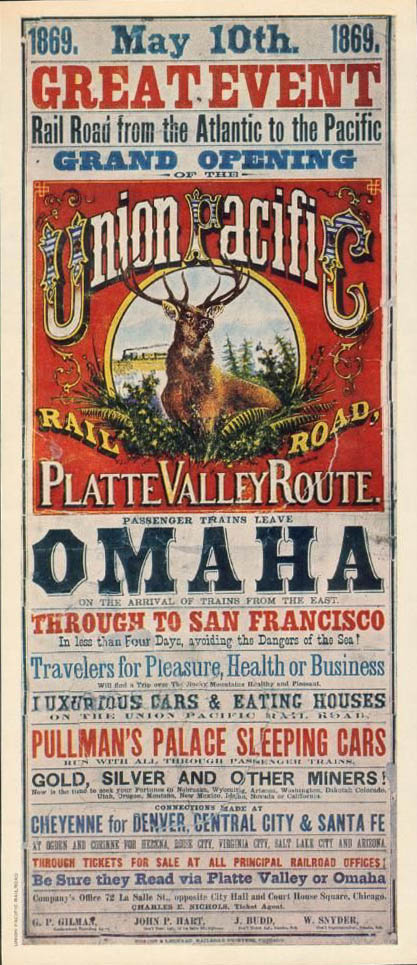

The official poster announcing the Pacific Railroad’s grand opening

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – Here, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=783367)

Here’s a concise but detailed look at the economics of the Transcontinental Railroad in the 1870s and beyond:

1. Expansion of National Markets

- The railroad unified the U.S. economy by linking eastern industrial centers with western farms, ranches, and mines.

- Goods such as grain, cattle, lumber, and minerals could now reach East Coast markets quickly and affordably.

- Manufactured products from the East flowed westward, fueling settlement and consumption.

2. Transportation Revolution

- Travel time across the continent dropped from months to just about a week.

- Freight costs plummeted, which made products more affordable and markets more competitive.

- Standardized time zones (introduced in 1883) were a direct byproduct of railroad scheduling needs.

3. Labor and Immigration

- Built largely by immigrant labor (Chinese in the West, Irish in the East).

- After completion, the railroad stimulated further immigration by making travel cheaper and encouraging European settlement in the Great Plains.

4. Agricultural Growth

- The Great Plains became the “breadbasket” of America. Farmers could ship wheat and corn to distant markets.

- Railroad companies themselves became powerful landowners, selling millions of acres of land (granted by the federal government) to settlers.

5. Industrial Growth

- Demand for steel rails, locomotives, coal, and construction materials spurred American industry.

- Railroads became the largest non-governmental employers and a testing ground for large-scale corporate management.

6. Capital and Finance

- Railroad expansion was financed through government bonds, land grants, and private capital (including European investment).

- Corruption scandals (e.g., Crédit Mobilier) revealed the immense political and financial stakes associated with the railroad industry.

- By the 1880s, railroads represented the single largest sector of U.S. capital investment.

7. Regional Development

- Mining towns, cattle ranches, and new cities (like Denver, Cheyenne, and Omaha) flourished along the tracks.

- The Western population soared, transforming territories into states.

8. Beyond the 1870s

- Railroads drove urbanization by funneling people and goods into growing cities.

- They became networked systems rather than single lines, knitting the country together economically and socially.

- By the 1890s, railroads were at the heart of the Populist movement, as farmers protested unfair freight rates and monopolistic practices.

⚖️ Overall:

The Transcontinental Railroad was one of the most important economic engines of 19th-century America. It lowered costs, expanded markets, fueled immigration, stimulated industry, and accelerated the rise of the U.S. as a continental power.

Would you like me to create a chronological table of economic impacts (1870s–1900s) that illustrates how the railroad’s effects unfolded over time?

Political Impacts of the Transcontinental Railroad

Great question! The Transcontinental Railroad wasn’t just an economic project—it had massive political implications in the 1870s and beyond. Here’s a breakdown of the politics of the railroad:

1. Federal Power & Expansion

- The project was authorized by the Pacific Railway Acts (1862 & 1864), showing how deeply the federal government was involved in directing infrastructure.

- Set the precedent for federal support of big business through land grants, subsidies, and regulation.

- Strengthened Washington’s ability to bind together far-flung regions, reinforcing national unity after the Civil War.

2. Statehood and Territorial Integration

- The railroad accelerated the admission of western territories into the Union (e.g., Colorado, 1876).

- Helped enforce federal authority in the West by moving troops quickly, crucial for suppressing uprisings and enforcing U.S. law.

- Politically reshaped, Congress saw new western states bring in senators and representatives, shifting the balance of power.

3. Native American Displacement

- Politically justified under “Manifest Destiny,” the railroad became the tool of Native American dispossession.

- Facilitated U.S. Army campaigns against tribes in the 1870s, breaking Native resistance.

- Indian policy (e.g., the reservation system, Dawes Act 1887, and later on) was politically tied to the expansion of railroads and the settlers they carried.

4. Corruption & Scandal

- The Crédit Mobilier scandal (1872) exposed deep corruption between railroad executives and members of Congress.

- Became a symbol of Gilded Age politics, where railroads wielded enormous influence over lawmakers.

- Raised debates over corporate power, bribery, and the integrity of government.

5. Railroad Lobby & Political Power

- Railroad corporations became major political players, lobbying for favorable laws, land, and subsidies.

- They influenced tariffs, land distribution, and regulation.

- By the 1880s, the railroad “barons” (like Collis P. Huntington and Jay Gould) were seen as more powerful than politicians in some regions.

6. Regulation and Reform

- The political backlash led to the Granger Movement in the 1870s, as farmers protested against railroad monopolies.

- Resulted in state-level railroad commissions regulating rates.

- Culminated in federal intervention: Interstate Commerce Act (1887), the first federal law to regulate private industry.

7. Shaping National Politics

- Railroad interests often decided elections, funding campaigns at the state and federal levels.

- Western settlement created new political constituencies (farmers, miners, ranchers) who challenged Eastern industrial dominance.

- Politically, the railroad helped transform the U.S. into a continental empire—a centralized federal state with reach from coast to coast.

⚖️ In summary:

The Transcontinental Railroad politicized everything from corruption to Native policy. It expanded federal power, reshaped Congress, fueled scandals, empowered corporate lobbying, and triggered reform movements. Politically, it was the engine of the Gilded Age.

Would you like me to make a timeline-style table (1870s–1900s) that compares political events tied to the railroad with their consequences?

“Manifest Destiny” Impacts of the Transcontinental Railroad

American Progress (1872) by John Gast is an allegorical representation of the modernization of the New West. Columbia, a personification of the United States, is shown leading civilization westward with the American settlers. She is depicted bringing light from east to west, stringing telegraph wire, holding a schoolbook, and highlighting different stages of economic activity and evolving forms of transportation.

(Wiki Image By John Gast – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs divisionunder the digital ID ppmsca.09855.This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=373152)

The Transcontinental Railroad was the most powerful engine of Manifest Destiny, transforming the abstract 19th-century belief in a coast-to-coast American empire into a concrete reality. It physically and psychologically stitched the nation together, accelerating settlement, economic growth, and the conquest of the West.

Here are the key impacts of the railroad on the concept of Manifest Destiny.

1. The Annihilation of Time and Space: A Nation United

Before the railroad, crossing the continent was a perilous six-month journey by wagon or sea. The railroad crushed this barrier.

- Drastic Reduction in Travel Time: The journey from New York to California was reduced from about six months to a single week.

- National Unification: This newfound speed and connectivity bound the distant state of California and the western territories firmly to the Union, a development especially crucial in the years following the Civil War. The railroad provided a physical “iron spine” for the nation, making the United States a true continental power.

2. The Engine of Western Settlement

The railroad made the mass settlement of the West possible and inevitable. The federal government used the railroad as its primary tool to encourage migration.

- Land Grants: The Pacific Railway Acts allocated millions of acres of public land to railroad companies, which then sold it to settlers at low prices to finance construction and create new customers.

- Creation of Towns: Towns and cities erupted all along the railroad’s path. Many, like Reno, Cheyenne, and Laramie, were born as railroad depots and service stops, forming the backbone of new western states.

- Immigration: The railroad companies actively recruited immigrants from Europe and workers from China, providing the labor to build the line and the people to settle the new lands it opened up.

3. The Conquest of the West and Subjugation of Native Peoples

For the Native American tribes of the Great Plains, the Transcontinental Railroad was a devastating disaster and a powerful tool of conquest.

- Destruction of the Bison: The railroad enabled the near-extermination of the American bison. It brought commercial hunters who slaughtered the herds by the million for their hides, destroying the primary source of food, shelter, and spiritual identity for the Plains Indians.

- Appropriation of Land: The railroad cut directly through ancestral and treaty-guaranteed lands, bringing waves of settlers into direct and violent conflict with the tribes.

- Military Advantage: It allowed the U.S. Army to move troops and supplies rapidly across the vast plains, effectively ending the Native American wars by the 1880s.

4. The Creation of a National Economy

The railroad created a truly national, integrated economy for the first time. It connected the industrial factories of the East with the immense natural resources of the West.

- Flow of Resources: Western lumber, minerals, cattle, and agricultural products could now be shipped quickly and cheaply to eastern markets.

- Opening Asian Trade: It fulfilled the long-held dream of connecting to the Pacific, opening up lucrative trade with Asia through ports like San Francisco.

In short, the Transcontinental Railroad was the literal fulfillment of Manifest Destiny’s promise, building a continental empire while also inflicting an enormous and tragic human and environmental cost.

Chronology of the Transcontinental Railroad (1830s–1870s) table

| Year | Event | Significance |

| 1830s–1840s | Early discussions about a railroad linking the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. | Sparked by westward migration and Manifest Destiny ideals. |

| 1856 | Theodore Judah surveys the Sierra Nevada Mountains. | Lays the groundwork for a feasible western route. |

| 1862 | Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act. | Authorizes Union Pacific (eastward build) and Central Pacific (westward build); provides land grants and loans. |

| 1863 | Construction officially begins in Sacramento, CA (Central Pacific) and Omaha, NE (Union Pacific). | Marks the start of the greatest engineering project of its time. |

| 1865 | Civil War ends; thousands of Union veterans join the railroad workforce. | Provides manpower and expertise for Union Pacific. |

| 1865–1869 | Brutal construction: Chinese laborers drive a track through the Sierra Nevada; Irish immigrants and freedmen lay track across the Great Plains. | Overcomes immense labor, terrain, and climate challenges. |

| 1867 | Grenville Dodge becomes the chief engineer of the Union Pacific. | Directs rapid progress westward across Nebraska and Wyoming. |

| 1868 | Leland Stanford and the “Big Four” finance the Central Pacific expansion. | Keeps Western progress alive through steep mountain passes. |

| May 10, 1869 | Golden Spike ceremony at Promontory Summit, Utah. | Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads meet—Transcontinental Railroad completed. |

| 1870s (Beyond) | Railroads expand into feeder lines, connecting to towns, farms, and mines. | Creates a continental market, accelerates settlement, and displaces Native populations. |

🚂 This table shows the step-by-step march from dream → law → construction → completion.

Would you like me also to create a map-style diagram (a visual timeline with routes converging at Promontory Summit) so you can see the east and west buildings moving toward each other?

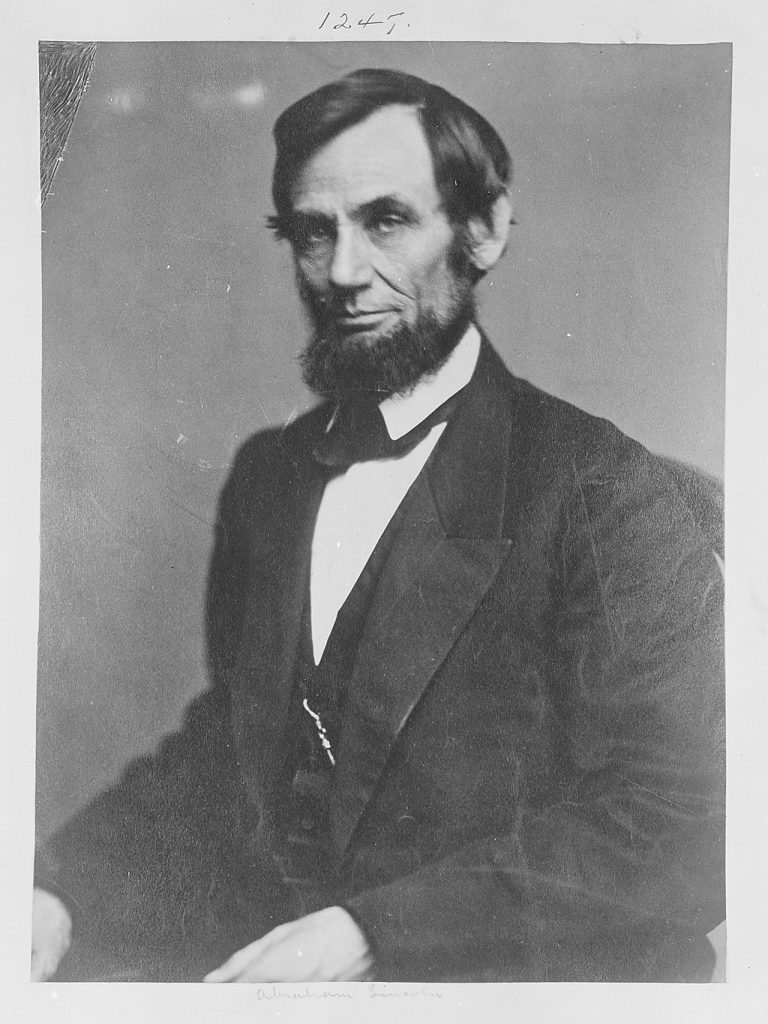

Abraham Lincoln: The Political Visionary

Portrait of Lincoln c. 1862

(Wiki Image By Mathew Benjamin Brady – U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17095016)

Abraham Lincoln: Transcontinental Railroad: Quotes

Abraham Lincoln, who began his career as a railroad lawyer, viewed the Transcontinental Railroad not merely as a commercial venture but as a vital tool for national unity and military security. His most famous and pertinent quote reflects this belief:

Key Quotes on the Transcontinental Railroad

On the Necessity of Union:

“A transcontinental railroad, Lincoln hoped, would bring the entire nation closer together – would make Americans across the continent feel like one people.“

— Description of Lincoln’s view on the railroad’s purpose (Union Pacific historical document)

On Directing the Project:

“The road must be built, and you are the man to do it. Take hold of it yourself. By building the Union Pacific, you will be the remembered man of your generation.“

— Attributed to President Lincoln in a conversation with Oakes Ames, a key financier of the Union Pacific Railroad, 1865.

On the Project’s Urgency and Strategic Value:

“At the height of that war, with unity so much on his mind, President Lincoln sought a way to connect and secure the great expanse of our nation, to unite it entirely, from sea to shining sea.“

— Summary of Lincoln’s mindset when signing the Pacific Railway Act in 1862.

On the Final Design and Logistics:

Lincoln personally intervened to settle the dispute over the eastern terminus of the railroad. He issued a Presidential Decree that the Union Pacific would begin at Omaha-Council Bluffs, a decision that was crucial to the entire route. This personal involvement demonstrated his deep commitment to the project’s successful completion, viewing it as essential to the nation’s future.

Abraham Lincoln: Transcontinental Railroad: History

Abraham Lincoln’s connection to the Transcontinental Railroad was not accidental; it was a deeply strategic and personal commitment that defined a significant part of his presidency. He viewed the railroad as an essential tool for securing and uniting the vast American nation.

- The Railroad Lawyer

Before becoming President, Lincoln had a long history as a successful railroad attorney in Illinois. He understood the immense logistical and economic power of rail lines, which provided him with a unique expertise and enthusiasm for the transcontinental project.

In 1859, two years before his presidency, Lincoln made a critical trip to Council Bluffs, Iowa. There, he met with a young railroad engineer named Grenville M. Dodge. Lincoln spent hours with Dodge, absorbing his knowledge of the western terrain and the ideal route—a route that would follow the Platte Valley.

- The Pacific Railroad Act (1862)

Despite the nation being consumed by the Civil War, Lincoln considered the Transcontinental Railroad to be part of the war effort, believing it was vital for the Union’s security and future.

On July 1, 1862, President Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act into law. This monumental legislation officially launched the project, authorizing the charter of two companies—the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific—and providing them with massive financial assistance through government bonds and vast grants of public land. The Act’s long title defined its purpose: “to secure to the government the use of the same for postal, military, and other purposes.”

- Fixing the Eastern Terminus (1863)

Lincoln’s most direct and personal intervention came in selecting the railroad’s starting point. Amid intense political lobbying from various cities, Lincoln followed the advice of Grenville Dodge.

In 1863, he issued an executive order designating the eastern terminus of the Union Pacific Railroad as Council Bluffs, Iowa. This decision was crucial because it finalized the central route that would eventually connect the East and West coasts.

Lincoln would not live to see the Golden Spike driven at Promontory Summit in 1869, but his vision and legislative action were the indispensable starting points for one of America’s greatest engineering and unifying achievements.

Here is an image related to Abraham Lincoln and the Transcontinental Railroad:

This image likely illustrates Lincoln’s key role in the project. As President, he signed the Pacific Railway Acts of 1862 and 1864, which provided the land grants and financial incentives (government bonds) necessary to start and complete the massive undertaking by the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads, even while the nation was engulfed in the Civil War.

Abraham Lincoln: Transcontinental Railroad: The Railroad Lawyer: 1809-1859

Here’s a clear overview of Abraham Lincoln’s role as “The Railroad Lawyer” (1809–1859) in relation to the Transcontinental Railroad and railroad development in general:

Abraham Lincoln: The Railroad Lawyer (1809–1859)

Abraham Lincoln’s connection to the Transcontinental Railroad during the period of 1809–1859 was defined by his influential career as a lawyer and his deep commitment to the nation’s economic expansion.

Early Career and Political Philosophy (1830s–1840s)

Born in 1809, Lincoln’s political and professional life was built on a Whig philosophy that championed internal improvements. As a member of the Illinois legislature in the 1830s, he was a vocal supporter of canals and railroads, viewing them as essential to integrating the growing American economy. His interest in connecting the nation by rail predated his presidency by decades.

The Railroad Lawyer (1850s)

The 1850s marked the busiest and most profitable period of Lincoln’s legal career, with railroad litigation becoming his specialty.

- Key Client: Illinois Central Railroad: The Illinois Central was, at one time, the largest corporation in the country, and Lincoln served as one of its most prominent attorneys. He was on retainer and handled over 50 cases for the company, earning significant fees.

- The Effie Afton Case (1857): This was Lincoln’s most famous railroad case, in which he successfully defended the Rock Island Railroad’s right to build the first bridge across the Mississippi River. The case legally established the precedent that railroads had the right to cross navigable waterways, a victory crucial to the future of the Transcontinental Railroad.

- Master of Logic: His work gave him an unparalleled understanding of railroad finance, land grants, engineering feasibility, and corporate law—knowledge he would later apply as president.

The Pivotal Meeting (1859)

In August 1859, while touring Iowa on personal legal business, Lincoln made a critical side trip to Council Bluffs. There, he met with a young railroad engineer named Grenville M. Dodge.

- Gathering Intelligence: Lincoln, who was already contemplating a transcontinental route, questioned Dodge for hours about the best path for a railroad through the West. Dodge’s recommendation to follow the Platte Valley and start at Council Bluffs convinced Lincoln, who later recalled that Dodge had “completely shelled my woods” (extracted all his secrets).

- A Vision Realized: This meeting was the moment the theoretical idea of a transcontinental railroad solidified into a practical plan in Lincoln’s mind. Two years later, as President, he used this exact intelligence to designate the eastern terminus, setting the Union Pacific in motion.

Abraham Lincoln: Transcontinental Railroad: The Pacific Railroad Act: 1860-1862

The period from 1860 to 1862 was a pivotal historical window during which the political and logistical groundwork for the Transcontinental Railroad was finally achieved, largely due to two key developments that removed decades of legislative paralysis.

1860: The Republican Commitment

The Transcontinental Railroad was a central, high-priority plank in the Republican Party Platform of 1860, the election that brought Abraham Lincoln to the presidency.

- Political Mandate: The platform declared that a railroad to the Pacific was “imperatively demanded by the interests of the whole country” and pledged “immediate and efficient aid in its construction.”

- The Vision: Lincoln and his party viewed the railroad as a crucial component of their plan for national economic modernization—promoting free labor, internal improvements, and westward settlement—which stood in direct opposition to the Southern, agrarian economy.

1861: Secession Removes the Obstacle

For years, debates over the Transcontinental Railroad had been paralyzed by sectionalism. Southern politicians insisted on a southern route (often through Texas), while Northern interests pushed for a central route. This disagreement prevented Congress from authorizing any route.

- Political Breakthrough: The secession of the Southern states from the Union in 1861 effectively removed their opposition from Congress. The remaining Republican majority was then free to choose a central/northern route without fear of the legislation being blocked.

- Military Necessity: The outbreak of the Civil War transformed the project from a desired economic development into a military and strategic necessity. Lincoln and Congress urgently needed a way to secure the gold-rich state of California and the Oregon Territory, ensuring they remained in the Union and could quickly supply resources and troops if needed.

1862: Lincoln Signs the Pacific Railroad Act

In an act that cemented the railroad as a wartime measure for Union victory, Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act into law:

- Date: July 1, 1862

- The Mandate: The Act authorized the creation of the Union Pacific Railroad Company and endorsed the Central Pacific Railroad Company (formed in California).

- The Incentives: The law provided a historic level of government support, including immense land grants and federal bonds (loans) for every mile of track laid.

- The Purpose: The long title of the Act clearly stated its core motivation: “to secure to the Government the use of the same for postal, military, and other purposes.”

By signing this act in the middle of the Civil War, Lincoln decisively launched the greatest infrastructure project of the 19th century, viewing the “iron bond” as essential to preserving and uniting the nation.

Abraham Lincoln: Transcontinental Railroad: Fixing the Eastern Terminus: 1863 – 1865

The period from 1863 to 1865 was the crucial time when Abraham Lincoln formally secured the starting point for the Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR). This action directly enabled its construction despite the raging Civil War.

1863: The Presidential Decree

Though the Pacific Railway Act was signed in 1862, it deliberately left the UPRR’s eastern starting point ambiguous, only stating it should be “on the western boundary of the State of Iowa to be fixed by the President.” Numerous towns lobbied fiercely for the designation.

- Lincoln Summons Dodge: In 1863, Lincoln summoned Brigadier General Grenville M. Dodge—a trusted Civil War engineer and railroad expert—to the White House to advise him. Dodge, relying on his pre-war surveys, adamantly insisted the terminus must be at Council Bluffs, Iowa, across the Missouri River from Omaha, Nebraska, because the Platte Valley offered the best engineering route west.

- The Executive Order: Following Dodge’s advice, Lincoln issued an executive order on November 17, 1863, officially fixing the eastern terminus in the Council Bluffs township, across the river from Omaha. This decree settled the dispute and provided the UPRR with a concrete starting point to finally begin construction.

- Construction Begins: The Union Pacific broke ground in December 1863 in Omaha, Nebraska Territory, beginning the ceremonial start of its 1,000-mile journey west.

1864–1865: Delays and Lincoln’s Death

Despite the formal start, the UPRR struggled in the years that followed:

- The Civil War: Resources, materials, and men were consistently diverted to the Union war effort, hindering the UPRR’s progress. The Central Pacific, meanwhile, was slowly laying track from Sacramento.

- The Pacific Railroad Act of 1864: To counter the slow progress and difficulty in raising funds, Lincoln signed an amendment to the Pacific Railroad Act, which doubled the land grants and made the financial incentives more appealing to investors.

- Lincoln’s Unfinished Vision: Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865, just three months before the Union Pacific finally laid its first functional rail. Though he never saw the rails laid, his personal commitment and decisive executive action in 1863 were essential in launching the railroad that would symbolically and physically unite the nation he died defending.

Transcontinental Railroad YouTube Video Links Views Abraham Lincoln

Here are some YouTube video links related to Abraham Lincoln and the Transcontinental Railroad:

- Abraham Lincoln and the Transcontinental Railroad by Union Pacific (Abraham Lincoln and the Transcontinental Railroad) – Published 2012-08-09, 41,470 views.

- Abraham Lincoln and the Transcontinental Railroad by Looking for Lincoln (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b7hqDbmeNrQ) – Published 2021-07-15, 1,008 views.

- Coast to Coast: America’s First Transcontinental Railroad by Untold History (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8fjIE43cVsM) – Published 2021-09-01, 105,306 views.

- President Abraham Lincoln Commemorative Locomotive No. 1616 by Union Pacific (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UukvlECCPpY) – Published 2025-06-13, 7,453 views.

- Union Pacific – Abraham Lincoln’s Railroad Dream #business #startups by LearnRepeat (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tE_dj04aNGc) – Published 2023-08-16, 326 views.

Theodore Judah: The Engineering Dreamer

Portrait of Judah, c. 1862

(Wiki Image By Carleton Watkins – Transferred from en.wikipedia by SreeBot, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17725165)

Theodore Judah: Transcontinental Railroad: Quotes

Theodore Dehone Judah, an engineer obsessed with connecting the coasts, was nicknamed “Crazy Judah” by contemporaries who doubted his grand vision. His quotes and philosophy reflect his engineering certainty, his entrepreneurial drive, and his unwavering belief in the project’s historical importance.

On the Significance of the Railroad

Judah saw the transcontinental rail line as the only way to secure the Union and propel the nation forward. He wrote extensively, lobbying for its construction:

“It is an enterprise more important in its bearings and results to the people of the United States than any other project involving an expenditure of an equal amount of capital. It connects these two great oceans. It is an indissoluble bond of union between the populous States of the East, and the undeveloped regions of the fruitful West.”

— From Theodore Judah’s “A Practical Plan for Building the Pacific Railroad” (1857)

On His Personal Obsession

Judah dedicated his short life to the railroad, conducting exhaustive surveys that convinced him the route over the Sierra Nevada was possible. His wife, Anna, is often quoted to highlight the depth of his commitment:

“Everything he did from the time he left for California until his death was for the Great Continental Pacific Railroad. It consumed his time, money, brain, strength, body, and soul. It was the burden of his thoughts day and night.”

— Anna Judah, reflecting on her husband’s singular focus

On the Need for Engineering Certainty

Judah was a meticulous engineer who dismissed the casual surveys of the time. He understood that to secure financing, he needed concrete, undeniable evidence of the route’s feasibility:

“When a Boston capitalist is invited to invest in a Railroad project, it is not considered sufficient to tell him that somebody has rode over the ground on horseback and pronounced it practicable. … He must see a map and profile, must know the grades and curves, the depths and quantity of excavation… he must see for himself the obstacles to be encountered, and the difficulties to be surmounted.“

— From Theodore Judah’s “A Practical Plan for Building the Pacific Railroad” (1857)

This last quote perfectly encapsulates the engineer’s mindset that convinced the “Big Four” to back the Central Pacific Railroad.

Theodore Judah: Transcontinental Railroad: History

Profile of the Pacific Railroad from Council Bluffs/Omaha to San Francisco. Harper’s Weekly December 7, 1867

Profile of the Pacific Railroad from Council Bluffs/Omaha to San Francisco. Harper’s Weekly December 7, 1867

Theodore Dehone Judah was the visionary and engineering force behind the western leg of the Transcontinental Railroad, an accomplishment that consumed his professional life but which he did not live to see completed.

The Obsessed Engineer

A civil engineer by trade, Judah came to California in 1854 to work on the Sacramento Valley Railroad, the first railroad built west of the Mississippi River. Immediately, his attention turned to the immense challenge of crossing the Sierra Nevada mountains. His single-minded passion earned him the nickname “Crazy Judah.”

In 1860, he conducted meticulous surveys, eventually finding the only “practicable route” over the Sierra via the Donner Pass. This was his greatest technical feat, as he proved that the grade—the steepness of the incline—was manageable for a steam locomotive, confounding skeptics who thought it impossible.

Founding the Central Pacific Railroad

In 1861, Judah successfully recruited five wealthy Sacramento merchants—Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker (later known as the “Big Four”)—to invest in his scheme, leading to the formation of the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) Company.

He then tirelessly lobbied Congress in Washington, D.C., working as the official agent for the CPRR. He was instrumental in securing the passage of the Pacific Railway Act of 1862, which granted the CPRR vast land and bond subsidies necessary to finance the construction.

An Untimely End

Tragically, Judah’s obsession with the railroad eventually led to a bitter split with the “Big Four.” The businessmen were more interested in maximizing profits through federal subsidies—even by altering the surveyed route for higher payments—which clashed with Judah’s ethical and engineering principles.

In October 1863, Judah sold his share to his partners, intending to travel east to find new investors who would buy out the “Big Four” and restore him to control of the visionary project. However, while crossing the Isthmus of Panama, he contracted Yellow Fever. He died shortly after arriving in New York City in November 1863, just as the monumental task of building over his surveyed route was truly beginning.

Here is an image related to Theodore Judah and the Transcontinental Railroad:

Theodore Judah, often referred to as “Crazy Judah” for his obsessive nature, was the visionary engineer who discovered the key route through the Sierra Nevada mountains (Donner Pass) and served as the driving force behind the formation of the Central Pacific Railroad. This image likely depicts his portrait or one of the detailed maps and surveys he created, which convinced Congress and the “Big Four” to support the project.

Theodore Judah: Transcontinental Railroad: The Obsessed Engineer: (1826 – 1860)

The period from 1826 to 1860 encapsulates Theodore Judah’s life as the visionary engineer whose singular obsession made the Transcontinental Railroad possible.

1826–1853: Early Engineering and the Railroad Boom

Born in Connecticut in 1826, Judah was a product of the early American railroad boom. He was trained as a civil engineer at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (then known as Rensselaer Institute). He gained a reputation for tackling challenging projects in the Northeast, such as the difficult Niagara Gorge Railroad. By 1853, he was a distinguished professional in a new and rapidly growing field.

1854–1859: The California Obsession

In 1854, at the age of 28, Judah and his wife, Anna, traveled to California, where he took the position of Chief Engineer for the Sacramento Valley Railroad, the first commercial railroad built west of the Mississippi River.

- The Big Dream: While completing the short local line, Judah became consumed by the idea of a continental connection. In January 1857, he published a 13,000-word proposal titled “A Practical Plan for Building the Pacific Railroad,” in which he argued that only a detailed, specific engineering survey, not political consensus, could make the railroad happen.

- Lobbying Washington: In 1859, he traveled to Washington, D.C. to lobby Congress, but the political climate—paralyzed by the North-South debate over the route—left him frustrated. He returned determined to find a route and private backing first.

1860: Finding the Route and Validation

The year 1860 proved decisive for Judah and the entire project.

- The Discovery: In July 1860, Judah, with the assistance of local storekeeper Daniel “Doc” Strong, discovered the Donner Pass route over the formidable Sierra Nevada mountains. Judah’s subsequent detailed surveys showed a gradual, continuous rise that made the route technically feasible for a steam locomotive—a feat most engineers believed impossible.

- Proof: By the end of 1860, Judah had the indisputable engineering proof he needed. He quickly published his findings, declaring the route was the most practical one. This physical proof was the key that unlocked the necessary political and financial support for the next phase, the formation of the Central Pacific Railroad Company.

Theodore Judah: Transcontinental Railroad: Founding the Central Pacific Railroad: (1661-1862)

The period from 1861 to 1862 was the triumphant climax of Theodore Judah’s career, during which he successfully bridged the gap between his engineering dream and political reality, launching the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) into existence.

1861: Securing Private Capital and Incorporation

Having found a feasible route over the Sierra Nevada in 1860, Judah needed money to finance lobbying in Washington and to conduct his final, detailed surveys.

- Recruiting the “Big Four”: In early 1861, after failing to secure large investors in San Francisco, Judah successfully convinced a group of five Sacramento merchants to back his enterprise. These were: Leland Stanford, Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Charles Crocker, and jeweler James Bailey.

- Judah presented them with an undeniable proposition: the sheer volume of gold and silver trade from Nevada would make a transcontinental railroad an instant fortune.

- Official Launch: On June 28, 1861, the Central Pacific Railroad Company of California (CPRR) was formally incorporated. Judah was named the Chief Engineer, and Leland Stanford was elected President.

- The Final Survey: With their backing, Judah spent the summer and early fall of 1861 completing his meticulous route surveys over the Sierra, compiling a detailed report and a massive 66-foot-long map of the proposed alignment.

1862: The Legislative Triumph

In October 1861, Judah was authorized by the CPRR directors to travel to Washington, D.C., as the company’s official lobbyist. Judah’s work in Washington proved indispensable to the entire national project.

- Lobbying Power: Utilizing his deep knowledge, Judah became an active participant in the legislative process, serving as the clerk of the House subcommittee and secretary of the Senate subcommittee on the bill. He worked tirelessly to guide the legislation, arguing that the Civil War made a railroad to the Pacific a military and political necessity for preserving the Union.

- The Pacific Railway Act: Judah’s efforts, combined with the absence of Southern opposition, paid off. On July 1, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act into law, which chartered the Union Pacific and, most importantly for Judah, granted the CPRR massive land grants and government bonds (subsidies) to finance the western construction.

- The Famous Telegram: Judah immediately telegraphed his partners in California with a triumphant, if prophetic, message: “We have drawn the elephant, now let us see if we can harness him up.”

By the end of 1862, Judah had returned to California, having secured the engineering, financial, and political foundation for the Transcontinental Railroad in less than two years.

Theodore Judah: Transcontinental Railroad: An Untimely End: 1863 and Legacy

The year 1863 marked the tragic, sudden end of Theodore Judah’s life, just as his grand vision for the Transcontinental Railroad was beginning to materialize.

An Untimely End (1863)

Despite successfully securing the Pacific Railway Act in 1862 and serving as Chief Engineer, Judah spent 1863 in a bitter power struggle with the other principal investors of the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR)—the “Big Four” (Stanford, Huntington, Hopkins, and Crocker).

- The Conflict: The Big Four were more interested in maximizing personal profit through the generous federal subsidies than in Judah’s engineering integrity. They planned to inflate construction costs (a practice that later fueled the Crédit Mobilier scandal) and marginalize Judah’s authority.

- Final Act: Judah, disgusted by the corruption and determined to regain control of his pure engineering vision, made a bold move. He accepted the Big Four’s challenge to buy out their stakes for $100,000 each. In October 1863, he sailed for New York to find financiers willing to back him.

- Death: While crossing the Isthmus of Panama, Judah contracted Yellow Fever. He died shortly after reaching New York City on November 2, 1863, at the age of 37.

This death came just as the CPRR was laying its first few miles of track in Sacramento—a symbolic first step into the enormous task ahead.

Legacy: The Prophet of the Rail

Despite his death, Judah’s legacy remained the foundation of the CPRR’s success.

- The Route: The entire western portion of the Transcontinental Railroad, including the famously difficult route over the Sierra Nevada at Donner Pass, was built almost precisely according to Judah’s meticulous 1860 surveys. His engineering work proved that the seemingly impossible was feasible.

- The Blueprint: He was the individual who secured both private capital (from the Big Four) and federal legislative backing (through the 1862 Act) simultaneously, launching the entire project.

- The Name: Judah is immortalized as the true visionary of the line. Mount Judah, a peak in the Sierra Nevada near Donner Pass, and a locomotive on the CPRR line were named in his honor. Without his singular obsession and technical proof, historians generally agree that the Transcontinental Railroad would have been significantly delayed.

Transcontinental Railroad YouTube Video Links Views Theodore Judah

Here are some YouTube video links related to Theodore Judah and the Transcontinental Railroad:

- Theodore Judah: Chuck Spinks Presentation by Sacramento Historical Society Programs (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m8SmH1STPxw) – Published 2024-08-29, 112 views.

- Theodore Judah by OwDylan (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QemyVaJ0ZbQ) – Published 2011-02-24, 707 views.

- Transcontinental Railroad | Work of Giants | American History Tellers | Podcast by American History Tellers (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wEKly-YaVJU) – Published 2024-11-19, 1968 views.

- The Transcontinental Railroad AMAZING AMERICAN HISTORY DOCUMENTARY by Ale Guz (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p3DJSd8nEVM) – Published 2017-01-23, 107,855 views.

- FORGOTTEN AMERICANS — Theodore Judah by hourlynewscaster (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f3Rxw9Tlwe8) – Published 2016-02-20, 346 views.

This video provides a great visual context for Theodore Judah’s pivotal role in the railroad’s history. State Archives’ Theodore Judah’s ‘First Complete Rail Map of the Sierras’ Available Digitally

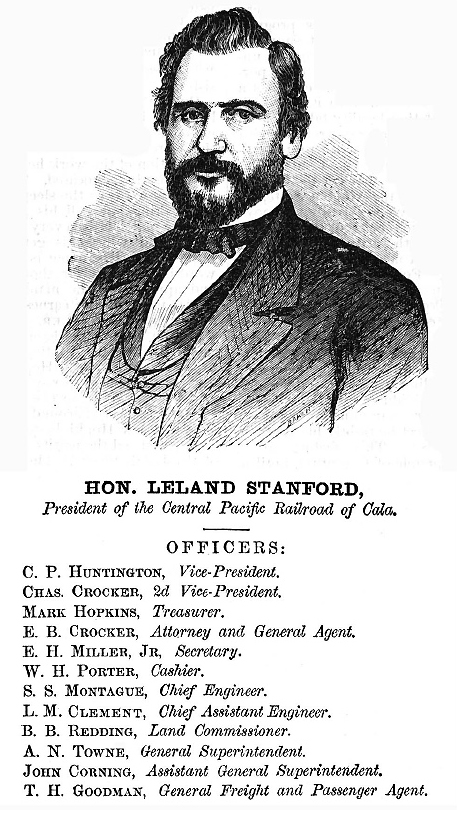

Leland Stanford: The Corporate Financier

Leland Stanford and the officers of the CPRR in 1870

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – Crofutt’s Trans-continental Tourists’ Guide. New York: Geo. A. Crofutt & Co., 1870, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=47213832)

Leland Stanford: Transcontinental Railroad: Quotes

Leland Stanford was the political face and president of the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) and is famously linked to the ceremony marking the railroad’s completion. His quotes reflect his roles as a visionary, politician, and spokesperson for the project, though the controversial nature of the enterprise often frames them.

On National Unity and the Golden Spike

Stanford’s most famous quote is not something he said during the ceremony, but a phrase that was engraved on the Golden Spike itself, capturing the perceived national significance of the achievement:

“May God continue the unity of our Country as this Railroad unites the two great Oceans of the world.”

— Inscription on the Golden Spike, driven by Leland Stanford at Promontory Summit, Utah, May 10, 1869.

After the historic moment, Stanford, alongside his counterparts from the Union Pacific, sent a succinct message telegraphing the completion across the nation:

“The last rail is laid! The last spike is driven. The Pacific Railroad is completed.”

— Telegram sent by Leland Stanford, T. P. Durant, and others, May 10, 1869.

On the Necessity of Chinese Labor

As President of the Central Pacific and former Governor of California, Stanford was initially known for his anti-Chinese rhetoric. However, the sheer impossibility of building the western leg of the railroad through the Sierra Nevada without an immense labor force forced him to change his public stance. His quotes on Chinese labor were primarily defensive and aimed at convincing Washington to allow their continued employment:

“Without them, it would be impossible to complete the western portion of this great national enterprise, within the time required by the Acts of Congress.”

— Statement made by Leland Stanford in a letter to U.S. President Andrew Johnson and the Secretary of the Interior, 1865.

On Labor and the Purpose of Capital

Later in his life, long after the railroad’s completion and in the context of founding Stanford University, he developed a more nuanced, progressive (though often debated) philosophy regarding labor and capital, which was heavily influenced by the railroad experience:

“From my earliest acquaintance with the science of political economy, it has been evident to my mind that capital was the product of labor, and that therefore, in its best analysis, there could be no natural conflict between capital and labor.”

— Leland Stanford, later in his career, reflecting on the relationship between wealth and work.

The Transcontinental Railroad was a Wild Stock Market

The history of the Transcontinental Railroad is inextricably linked to the concept of a volatile stock market and financial speculation. The entire project laid the foundation for one of the most spectacular boom-and-bust cycles of the Gilded Age, characterized by massive risk, government corruption, and a relentless pursuit of profit.

The railroad was essentially built on a massive speculative gamble:

- Built “Ahead of Demand”

The railroad was built through vast, largely unpopulated territory with virtually no existing towns, industry, or consumer base. This meant there was little to no immediate commercial traffic to generate profit. The companies were betting that the rail line itself would stimulate future settlement and economic activity, which would eventually make the route profitable.

- Financial Risk: This inherent risk meant that private investors were unwilling to fund the full $ 100 million+ cost without government guarantees. The value of the railroads’ stock and bonds was therefore based almost entirely on future expectations and government subsidies, rather than current revenue.

- The Gold Rush of Government Subsidies

The true engine of financial frenzy was the federal aid granted by the Pacific Railway Acts of 1862 and 1864. This created a perverse incentive system:

- Profit from Construction, Not Operation: The directors of both the Union Pacific (UP) and Central Pacific (CP) realized that the real, immediate money was to be made not by running a viable railroad, but by building it.

- The Scam: This led to the formation of fraudulent construction companies, such as the Crédit Mobilier of America (UP) and the Contract and Finance Company (CP). The railroad directors secretly owned these companies, awarded them inflated, above-cost contracts, and paid them with the government’s bond money. This practice siphoned millions of dollars in profit directly into the directors’ personal pockets.

- Corrupt Stock Deals: To protect this scheme from congressional oversight, UPRR director Oakes Ames distributed Crédit Mobilier stock to influential Congressmen at below-market value, making them secret partners in the illegal profits.

- The Collapse and The Panic of 1873

The rampant speculation in railroad stock and bonds created a financial bubble that eventually burst.

- The Overextension: Following the success of the first Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, investors poured money into subsequent, equally risky railroad ventures, such as the Northern Pacific Railway.

- The Crash: When the major banking firm of Jay Cooke and Company (a key financier of Northern Pacific) collapsed in September 1873, it triggered the Panic of 1873, plunging the U.S. into a severe, prolonged economic depression. Railroad stock was at the epicenter of the crisis, with nearly a quarter of all American railroads eventually going bankrupt.

In summary, the Transcontinental Railroad was less a steady business venture and more a high-stakes, volatile speculation machine that became the defining symbol of the financial mania and corruption of the Gilded Age.

Crédit Mobilier of America (UP) and the Contract and Finance Company (CP)

Here is a detailed breakdown of the two infamous, mirror-image companies that were created to build the First Transcontinental Railroad.

You are correct to link them. They were both dummy construction corporations set up by the executives of the Union Pacific (UP) and Central Pacific (CP), respectively. Their purpose was to perform a massive, fraudulent act of self-dealing.

The Basic Scam: How Both Companies Worked

Before the specific details, here is the brilliant (and corrupt) business model both companies used:

- The Problem: As an executive of the Union Pacific, you get massive government subsidies (land grants and bonds worth $16,000 to $48,000) for every mile of track you build. Your goal is to build the railroad, but you also want to pocket as much of that government money as possible.

- The “Solution”: You can’t just pay yourself directly. So, you create a separate, independent construction company (e.g., Crédit Mobilier).

- The Self-Dealing: You and your fellow executives secretly own all the stock in this new construction company.

- The Contracts: As an executive at Union Pacific, you award an enormously inflated, non-competitive contract to this “independent” construction company to do the actual construction.

- The Payout:

- Your construction company builds a mile of track for a real cost of $30,000.

- It then bills the Union Pacific for $70,000 (using the inflated contract).

- The Union Pacific pays the bill using the government subsidies and by issuing new railroad stock.

- The Result: Your construction company (which you own) earns $40,000 in cash and stock. The Union Pacific (the public company) is deeply in debt, but you and your inner circle become fabulously wealthy.

Both companies used this exact model. The only significant difference was their outcome.

1. Crédit Mobilier of America (Union Pacific)

This was the construction arm of the Union Pacific Railroad, which built the line west from Omaha, Nebraska.

- Key Players: Thomas C. Durant, Oakes Ames (a U.S. Congressman), and other Union Pacific directors.

- The Scheme: Durant and his associates bought a small, obscure Pennsylvania shell company called “Crédit Mobilier of America” and transformed it into their personal construction firm. They then awarded themselves contracts, with profits estimated at tens of millions of dollars.

- The Scandal (The Key Difference): The Crédit Mobilier scheme was poorly managed, and the partners fought constantly. When their massive fraud was threatened with a congressional investigation, Congressman Oakes Ames (who was also a major stockholder) was tasked with stopping it.

- The Bribes: To kill the investigation, Ames distributed shares of Crédit Mobilier stock at a very low price (or for free) to other influential congressmen and high-ranking officials. He famously wrote, “We want more friends in this Congress.”

- The Outcome: In 1872, the New York Sun broke the story, leading to a massive public scandal. The investigation implicated Vice President Schuyler Colfax and future President James Garfield, among many others. Crédit Mobilier became the defining political scandal of the Gilded Age, forever synonymous with post-Civil War corruption.

2. The Contract and Finance Company (Central Pacific)

This was the far more successful and secretive construction arm of the Central Pacific Railroad, which built the line east from Sacramento, California.

- Key Players: The “Big Four” of the Central Pacific: Leland Stanford, Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker.

- The Scheme: The Big Four owned the Central Pacific, but they needed someone to build it. They first created “Charles Crocker & Co.” (literally just one of them) and then replaced it with a more formal corporation: the Contract and Finance Company.

- The “Success”: This company was owned entirely by the Big Four. They awarded themselves all the contracts to build the Central Pacific, including the incredibly difficult and expensive route over the Sierra Nevada mountains. They operated with the same self-dealing model as Crédit Mobilier, paying themselves over $120 million in cash and stock for work that cost a fraction of that.

- The Outcome (No Scandal): This is the crucial difference. The Contract and Finance Company was not the subject of a public scandal. Why?

- Tight Control: It was secretly controlled by only four men, who trusted each other enough to keep the scheme quiet.

- Destruction of Evidence: In 1873, just as Congress was beginning to investigate the railroads (spurred by the Crédit Mobilier scandal), the “Big Four” had a problem: their books showed their massive, illegal profits. They burned all the records of the Contract and Finance Company, destroying the evidence.

Comparison Table

| Feature | Crédit Mobilier of America | Contract and Finance Company |

| Associated Railroad | Union Pacific (UP) | Central Pacific (CP) |

| Key People | Thomas C. Durant, Oakes Ames | The “Big Four” (Stanford, Huntington, Hopkins, Crocker) |

| Business Model | Dummy corporation to channel inflated contracts to its own owners. | Dummy corporation to channel inflated contracts to its own owners. |

| Route Built | From Omaha, Nebraska, westward (the plains). | From Sacramento, California, eastward (the Sierra Nevada). |

| Historical Outcome | A massive public scandal (1872) that exposed widespread bribery in Congress and defined Gilded Age corruption. | A successful, secret operation. The owners became fabulously wealthy, and the evidence was destroyed before it could cause a scandal. |

Here are four images representing the infamous financial entities connected to the construction and corruption surrounding the Transcontinental Railroad: the Crédit Mobilier of America (Union Pacific) and the Contract and Finance Company (Central Pacific). These images often include political cartoons that highlight the massive scale of the scandals.

The Transcontinental Railroad was a Wild Stock Market: Leland Stanford

Leland Stanford, as the President of the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) and a member of the “Big Four” collective, was a central player in the wild stock market and financial manipulation that characterized the Transcontinental Railroad project. His massive fortune was created not just by building the line, but by exploiting government subsidies through layers of corporate shell games.

The Mechanism of Speculation

Stanford and his partners were not primarily railroad men; they were business opportunists who recognized that the government’s liberal financing—land grants and bonds—made construction the most profitable venture of the age.

- The Fictitious Contractor: Stanford, Huntington, Hopkins, and Crocker created an ancillary construction company, first known as the Contract and Finance Company (similar to the Union Pacific’s Crédit Mobilier). They secretly owned and controlled this contracting firm.

- Contracting with Themselves: As CPRR directors, they would vote to award immensely lucrative construction contracts to their own side company. The Central Pacific would pay the Contract and Finance Company with the federal government’s bond money at grossly inflated prices.

- The Profit: This financial sleight-of-hand allowed Stanford and the Big Four to divert enormous amounts of public and private investment (which was financing the railroad) directly into their personal pockets (as contractors). As one historian noted, they were effectively “taking money into one hand as a corporation, and paying it out into the other as a contractor.”

Stanford’s Specific Role

- Political Lobbyist: Stanford’s most crucial corporate asset was his political power. As the sitting Governor of California at the start of construction, he used his influence to secure favorable state legislation and to successfully lobby Washington for the favorable terms of the Pacific Railway Act.

- Mountain Subsidy Scam: Stanford was a party to the controversial claim that the Sierra Nevada mountains started almost immediately outside of Sacramento. This geographic designation instantly qualified the CPRR for the highest tier of federal bonds ($48,000 per mile), regardless of the actual terrain difficulty. This manipulation ensured that the Big Four received maximum government funding for their personal profit.

The railroad’s stock market was wild because its value was driven more by speculation on government largesse and construction fraud than by the actual economic viability of running trains. This practice led to the Panic of 1873 and defined Stanford as a “Robber Baron.”

Leland Stanford: Transcontinental Railroad: History

Leland Stanford and the Iron Road: A Legacy Forged in Steel and Ambition

Leland Stanford, a name synonymous with both California’s Gilded Age and a prestigious university, played a pivotal role in one of the 19th century’s most audacious engineering feats: the construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad as one of the “Big Four” industrialists and the president of the Central Pacific Railroad, Stanford’s political influence, financial acumen, and unwavering ambition were instrumental in carving a path of steel across the formidable Sierra Nevada and uniting a nation.

From Merchant to Railroad Baron

A lawyer by trade, Leland Stanford arrived in California during the Gold Rush and established himself as a successful merchant in Sacramento. His entry into the world of railroads began with his association with Theodore Judah, a visionary engineer who had meticulously surveyed a viable route through the treacherous Sierra Nevada mountains. Convinced of the project’s feasibility and immense potential, Stanford, along with fellow Sacramento merchants Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker, formed the Central Pacific Railroad Company in 1861. This quartet would become known as the “Big Four,” the driving force behind the western portion of the transcontinental line.

Stanford’s political aspirations neatly dovetailed with his railroad ambitions. In 1861, he was elected Governor of California, a position that provided him with the political leverage to secure favorable legislation and state support for the monumental undertaking. His influence was crucial in the passage of the Pacific Railway Act of 1862, signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln. This act provided the Central Pacific and the newly formed Union Pacific Railroad with land grants and government bonds for each mile of track they laid, setting the stage for a dramatic race to connect the east and west coasts.

The Herculean Task of the Central Pacific

As president of the Central Pacific, Stanford oversaw the immense challenges of building eastward from Sacramento. The initial and most formidable obstacle was the Sierra Nevada. The construction required blasting 15 tunnels through solid granite, a painstaking and dangerous process. To overcome a severe labor shortage, the Central Pacific made the pivotal decision to hire thousands of Chinese laborers. This workforce, often overlooked in historical accounts, proved to be incredibly resilient and efficient, enduring brutal winters and perilous working conditions to lay the tracks that would conquer the mountains.

While Crocker managed the on-the-ground construction, and Huntington procured materials and financing in the East, Stanford’s role was one of leadership and political maneuvering. He worked to maintain government support, manage the company’s finances, and champion the project amid public skepticism and logistical nightmares. The transportation of every rail, locomotive, and piece of equipment to California by sea, a long and costly journey around Cape Horn or across the Isthmus of Panama, was a testament to the logistical hurdles they overcame.

The Golden Spike and a Nation United

The race between the Central Pacific, building east, and the Union Pacific, building west from Omaha, Nebraska, culminated on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit, Utah. In a ceremony that captured the nation’s imagination, Leland Stanford was given the honor of driving the final, ceremonial “Golden Spike” to join the two lines. Though his first swing with the silver maul famously missed its mark, the telegraph wires connected to the spike instantly flashed the news across the country: “DONE.”

The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad was a transformative moment in American history. It dramatically reduced the time and cost of cross-country travel and commerce, accelerating westward expansion and settlement. For Leland Stanford and the “Big Four,” it brought immense wealth and power, solidifying their status as railroad magnates.

The fortune Stanford amassed from the railroad would later fund the establishment of Stanford University, which he and his wife, Jane, founded in memory of their only son. While his legacy is complex and includes controversies over business practices and labor treatment, Leland Stanford’s indelible mark on American history is forever intertwined with the steel rails that bound a continent and propelled the nation into a new era of progress and connectivity.

Here is an image related to Leland Stanford and the Transcontinental Railroad:

This image likely depicts the iconic moment of the Golden Spike ceremony at Promontory Summit, Utah, on May 10, 1869. Leland Stanford, as the president of the Central Pacific Railroad and a member of the powerful “Big Four,” is famously shown driving the ceremonial spike that completed the nation’s first transcontinental line.

Leland Stanford: The Corporate Financier: 10 Stories

Leland Stanford’s career as a corporate financier and railroad magnate is a complex history of political maneuvering, leveraging government aid, and accumulating colossal wealth through monopolistic practices. As one of the “Big Four” owners of the Central Pacific and Southern Pacific Railroads, his story is inextricably linked to the crony capitalism of the Gilded Age.

Here are ten stories and examples that illustrate his methods and personality as a financier:

- The Governor’s Shovel: In 1863, Stanford, as the sitting Governor of California, ceremonially shoveled the first dirt for the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR). This dual role was no accident; it enabled him to utilize his executive power to channel state funds, land grants, and favorable legislation directly to his private company, thereby maximizing his fortune.

- Squeezing Out the Visionary: Stanford and the “Big Four” systematically marginalized and then squeezed out the company’s true founder and Chief Engineer, Theodore Judah. Judah’s insistence on engineering integrity over profit-padding led to a bitter dispute, in which the Associates used financial pressure to force him to sell his stake, which was far below its potential value.

- The Mountain Subsidy Scam: To profit from government subsidies, the Big Four had a significant incentive to claim the Sierra Nevada began as close to Sacramento as possible, as mountainous terrain earned triple the subsidy bonds ($48,000 per mile). Stanford, as the company president, approved maps that exaggerated the mountain line, enabling his group to bilk the government out of millions.

- The Central Pacific’s Construction Company (Contracting with Themselves): Stanford and his partners created an indirect construction company—the Contract and Finance Company—to award themselves the lucrative building contracts. By operating on both sides of the deal, they could drastically inflate construction costs and pocket the difference, effectively transferring taxpayer money into their private accounts.

- The Spite Fence of Nob Hill: After moving to San Francisco, Stanford built a magnificent mansion on Nob Hill. When his neighbor, Nicholas Yung, refused to sell his adjacent lot, Stanford built a massive 40-foot-high wooden fence around three sides of Yung’s property, intentionally blocking his light and view in an act of corporate spite.

- The Bank of California Bailout: In 1868, Stanford signed a $1 million draft without consulting his partners, leaving the CPRR unexpectedly captive to the powerful Bank of California. This rash, impulsive financial decision forced Mark Hopkins and Collis Huntington to scramble to prevent a major economic disaster for the company.

- Exploitation of Chinese Labor: To conquer the Sierra, the CPRR relied almost entirely on Chinese immigrant labor. Stanford’s management ensured Chinese workers were paid less than their white counterparts and had to pay for their own board. When 3,000 workers went on strike in 1867, demanding equal pay, Stanford and Crocker famously cut off their food and supplies until the strike was broken.

- The Ousting by Huntington: The business relationship among the Big Four was famously contentious. In a twist of corporate power, Collis Huntington, a far more effective long-distance lobbyist, led a coup in 1890 to oust Stanford from the Presidency of the Southern Pacific Railroad (which controlled the CPRR). This was seen as retaliation for Stanford’s separate pursuit of political power as a U.S. Senator.

- The Government Lawsuit (Post-Mortem): After Stanford died in 1893, the government filed a lawsuit against his estate to recover long-overdue railroad loans. The resulting financial freeze nearly led to the collapse of the newly founded Stanford University, forcing his wife, Jane, to fight a six-year legal battle and to manage the university with her personal funds.

- The Forgotten Cooperative Vision: In his later years, after accumulating his immense fortune, Senator Stanford advocated for the end of capitalism, proposing that worker-owned cooperatives replace the corporate system. He even wrote this cooperative vision into the founding grant for Stanford University—a stunning, if forgotten, ideological shift by a man notorious for his “robber baron” practices.

Transcontinental Railroad YouTube Video Links Views Leland Stanford

Here are some YouTube video links related to Leland Stanford and the Transcontinental Railroad:

- The Transcontinental Railroad at 150: Reflections on the History of the American West by Stanford Historical Society (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3BOJ5IjnYOg) – Published 2021-08-10, 919 views.

- Leland Stanford: The Controversial Life of America’s Western Railroad Tycoon by Biographics (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RM92AWoDJeQ) – Published 2021-08-19, 139,189 views.

- Anti-Chinese Man Established Stanford!? by Graham Elwood Clips (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jAr1HLOFi4g) – Published 2023-04-10, 139 views.

- The Transcontinental Railroad AMAZING AMERICAN HISTORY DOCUMENTARY by Ale Guz (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p3DJSd8nEVM) – Published 2017-01-23, 107,856 views.

- Leland Stanford: The Man Who Connected America by American History Figures (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5VbdBPef5jQ) – Published 2024-10-08, 727 views.

Grenville Dodge: The Master of Construction

Maj. Gen. Grenville M. Dodge

(Wiki Image By Civil War Glass Negatives – Library of CongressCatalog: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/cwp2003000305/PPOriginal url: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cwpb.05485, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65970773)

Grenville Dodge: Transcontinental Railroad: Quotes

Grenville Mellen Dodge, the Chief Engineer of the Union Pacific Railroad, was a Civil War General whose discipline and military-grade planning were key to the railroad’s success. His quotes and recollections reflect his engineering confidence, his contentious business dealings, and his ruthlessly pragmatic view of the conflict with Native American tribes.

On His Critical Meeting with Abraham Lincoln

Dodge’s most famous quotes relate to his 1859 meeting with Abraham Lincoln, which led to the selection of the railroad’s eastern terminus. Dodge recounted how the future President questioned him closely on the best route:

“He completely ‘shelled my woods,’ getting all the secrets that were later to go to my [railroad] employers.”

— Grenville Dodge, recalling how Lincoln extracted every piece of knowledge he had on the western routes during their meeting in Council Bluffs, Iowa.

Dodge also confidently asserted the best route, which Lincoln later formalized:

“The railroad must follow the Platte Valley and begin at Omaha-Council Bluffs.”

— Grenville Dodge, advising President Lincoln on the eastern terminus and route.

On the Conflict with Native Americans

Dodge was a military man who viewed the Native American tribes blocking the railroad’s path as a logistical obstacle to be eliminated. His attitude was unsentimental and uncompromising:

“We’ve got to clean the damn Indians out or give up building the Union Pacific Railroad. The government may take its choice.”

— Grenville Dodge, expressing his ruthless pragmatism about the conflict over the land required for the railroad’s construction.

On the Completion of the Railroad

Despite his battles with fraudulent investors like Thomas “Doc” Durant, Dodge took immense pride in the engineering feat. His work at the end of the line was a moment of personal triumph:

“All honor to you, to Durant, to Jack and Dan Casement, to Reed, and the thousands of brave fellows who have wrought out this glorious problem, spite of changes, storms, and even doubts of the incredulous, and all the obstacles you have now happily surmounted.”

— Grenville Dodge, in a telegram on the day the Golden Spike was driven, acknowledged the thousands of workers who made the impossible task a reality.

Grenville M. Dodge: A Legacy of Engineering and Innovation

Grenville Mellen Dodge, a pivotal figure in 19th-century American expansion, left an indelible mark on the nation’s landscape through his exceptional engineering prowess, particularly in the realm of railroad construction. His career, marked by both military and civilian achievements, was instrumental in the development of the American West.

Born in Danvers, Massachusetts, in 1831, Dodge’s early aptitude for engineering led him to a career that would shape the country’s infrastructure. His most celebrated accomplishment was his role as the chief engineer of the Union Pacific Railroad during the construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad. Appointed to the position in 1866, Dodge was responsible for surveying and overseeing the construction of over 1,000 miles of track, a monumental feat that connected the eastern and western United States and revolutionized transportation and commerce.

Dodge’s engineering acumen was not confined to civilian projects. During the Civil War, he served as a major general in the Union Army, where his skills were crucial in military logistics. He was renowned for his rapid reconstruction of bridges and railway lines destroyed by Confederate forces, earning him a reputation as a brilliant military engineer. His ability to quickly restore vital transportation networks was a significant factor in the Union’s success.

Throughout his career, Dodge was involved in the construction of numerous other railway lines, contributing to the vast expansion of America’s rail network. His vision and technical expertise were sought after for various projects, solidifying his status as one of the preeminent engineers of his time.

The following table details some of Grenville Dodge’s most significant engineering projects:

| Project | Role | Time Period | Location | Significance |

| First Transcontinental Railroad | Chief Engineer | 1866-1869 | Omaha, Nebraska, to Promontory Summit, Utah | Oversaw the construction of the Union Pacific’s portion of the railroad, uniting the country by rail. |

| Reconstruction of Mobile & Ohio Railroad | Union Army Corps of Engineers | During the Civil War | Southern United States | Rapidly repaired and rebuilt crucial railway infrastructure to support the Union war effort. |

| Pope’s Railroad (Survey) | Surveying Engineer | 1853 | American Southwest | Surveyed a potential route for a transcontinental railroad along the 32nd parallel. |

| Texas & Pacific Railway | Consulting Engineer | Post-Civil War | Southern United States | Provided expertise for the construction of this major railway line. |

| Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railway | Chief Engineer | Post-Civil War | Missouri, Kansas, and Texas | Led the engineering efforts for the expansion of this key railroad in the central United States. |

Grenville Dodge: Transcontinental Railroad: History

Grenville Mellen Dodge’s history with the Transcontinental Railroad is a story of military precision, engineering brilliance, and political influence that proved essential to the Union Pacific’s success.

- The Pre-War Vision and Lincoln’s Decree

Dodge was a civil engineer who was deeply involved in surveying rail lines in the Midwest long before the Civil War. His expertise was recognized by Abraham Lincoln, whom he met in Council Bluffs, Iowa, in 1859. Dodge advised Lincoln on the best route, advocating for the Platte Valley—a route Lincoln later formalized.

In 1863, while serving as a Brigadier General, Dodge was summoned by Lincoln to Washington, D.C., to resolve the contentious issue of the railroad’s starting point. Lincoln ultimately issued an executive order setting the eastern terminus at Council Bluffs, Iowa, following Dodge’s recommendation. This decision, influenced by Dodge’s professional judgment, was critical to starting the Union Pacific’s construction.

- Military Background and Engineering Discipline

Dodge’s experience as a General during the Civil War was invaluable to the railroad project. He gained a reputation for being able to “rebuild a railroad faster than the Confederates could cut them,” a skill he later applied to the Union Pacific.