André Le Nôtre, Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, and Frederick Law Olmsted: Gardeners

André Le Nôtre, Lancelot “Capability” Brown, and Frederick Law Olmsted were three of the most influential figures in the history of landscape architecture, each leaving an indelible mark on their respective eras and regions.

André Le Nôtre (1613-1700): The Master of French Formal Gardens

- Style: Le Nôtre pioneered the jardin à la française (French formal garden), characterized by its grand scale, geometric precision, and intricate parterres. He used straight lines, axes, symmetry, and ornate water features to create imposing landscapes that showcased man’s power and control over nature.

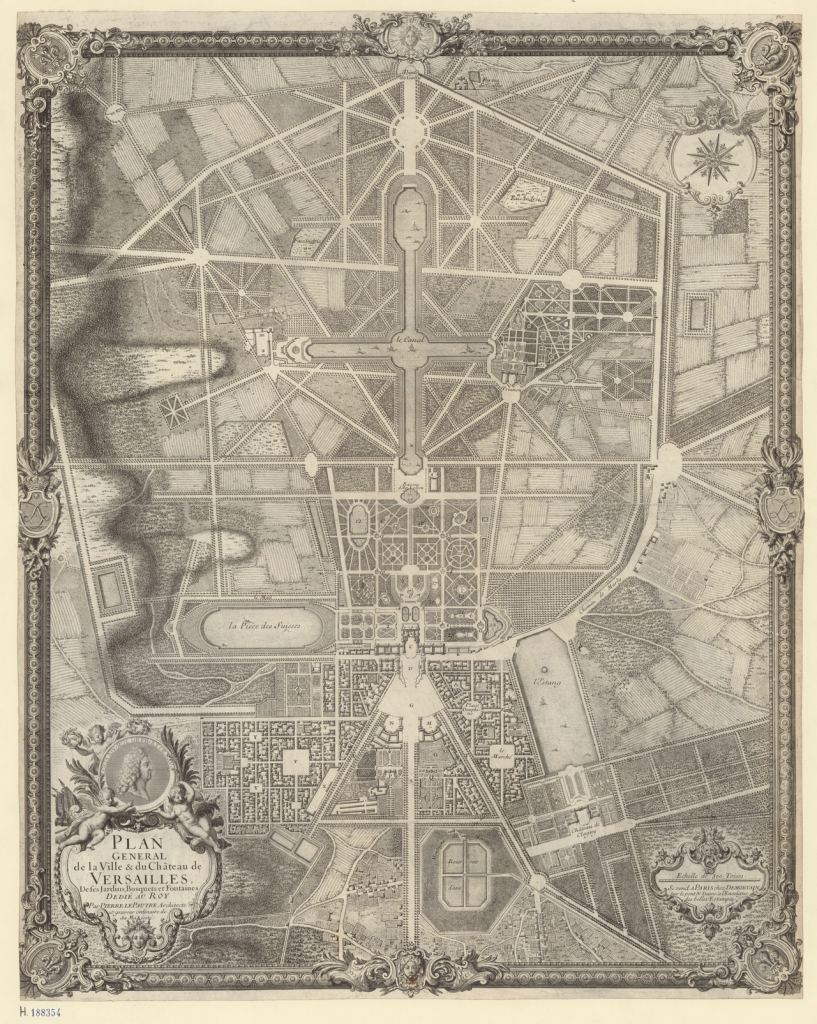

André Le Nôtre’s Gardens of Versailles

- Philosophy: His gardens reflected the absolute monarchy and the Age of Enlightenment, emphasizing order, reason, and human dominance over the natural world.

- Famous Works: Gardens of Versailles, Vaux-le-Vicomte, Château de Chantilly

Lancelot “Capability” Brown (1716-1783): The Pioneer of English Landscape Gardens

- Style: Brown revolutionized English landscape design with his naturalistic style, which sought to create an idealized vision of nature. He replaced formal gardens with rolling lawns, serpentine lakes, and strategically placed clumps of trees, creating a sense of harmonious balance and tranquility.

Lancelot Capability Brown’s Stowe Landscape Garden

- Philosophy: Brown believed gardens should be an extension of nature, seamlessly blending with the surrounding landscape and evoking a sense of peace and serenity.

- Famous Works: Blenheim Palace, Stowe Landscape Garden, Chatsworth House

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903): The Father of American Landscape Architecture

- Style: Olmsted pioneered the design of urban parks, creating vast green spaces that offered city dwellers a respite from the noise and pollution of industrialization. His designs emphasized natural beauty, incorporating elements like meadows, woodlands, and water features.

Frederick Law Olmsted’s Central Park

- Philosophy: Olmsted believed that parks were essential for the physical and mental well-being of urban populations, providing opportunities for recreation, relaxation, and social interaction. He also believed that parks could promote democratic values and social cohesion.

- Famous Works: Central Park (New York City), Prospect Park (Brooklyn), Emerald Necklace (Boston)

Overall Comparison:

These three landscape architects, each with a unique style and philosophy, shaped how we think about and interact with the natural world. While their approaches differed, they all shared a deep appreciation for nature’s beauty and restorative power and a desire to create spaces that benefit humanity.

André Le Nôtre History

A portrait of André Le Nôtre by Carlo Maratta (Wiki Image).

“The garden must be adorned in such a manner that it reflects the elegance and grandeur of the palace.” – André Le Nôtre.

“There is no greater artist than nature; it is my task to arrange her elements in a way that enhances her beauty.” – André Le Nôtre.

“Symmetry and order are the principles upon which all great gardens are built.” – André Le Nôtre.

“A garden should be a place of both beauty and utility, where every element has its purpose and place.” – André Le Nôtre.

“Gardens are a means of showing the mastery of man over nature, demonstrating the power and control that can be achieved through design.” – André Le Nôtre.

“The true beauty of a garden lies not just in its plants and flowers, but in the harmony and balance of its design.” – André Le Nôtre.

“My gardens are an extension of the palace’s architecture, seamlessly blending indoor and outdoor spaces.” – André Le Nôtre.

“In every garden, I strive to create a sense of grandeur and magnificence, worthy of the kings and queens who will enjoy them.” – André Le Nôtre.

“The use of water in a garden, through fountains and canals, brings life and movement to the design.” – André Le Nôtre.

“Every path, every tree, and every flower must contribute to the overall harmony of the garden; nothing should be out of place.” – André Le Nôtre.

| Year | Age | Events, Projects & Patrons |

|---|---|---|

| 1613 | 0 | Born in Paris, France (March 12th) into a family of gardeners. His father, Jean Le Nôtre, was the royal gardener at the Tuileries Palace. |

| 1637 | 24 | He was appointed head gardener of the Tuileries Garden, succeeding his father. |

| 1645-1649 | 32-36 | Begins work on the gardens at Vaux-le-Vicomte for Nicolas Fouquet, Superintendent of Finances. Collaborates with architect Louis Le Vau and painter Charles Le Brun. |

| 1656 | 43 | He completes the gardens at Vaux-le-Vicomte, a masterpiece that establishes his reputation. |

| 1661 | 48 | Begins work on the gardens at Versailles for King Louis XIV. This becomes his most ambitious and renowned project. |

| 1662 | 49 | Designs the gardens at Fontainebleau for Louis XIV. |

| 1664 | 51 | Louis XIV ennobled him, granting him the title “André Le Nôtre, sieur de Foucy.” |

| 1660s – 1680s | 50s – 70s | Continued to expand and refine the gardens at Versailles, creating a vast and elaborate landscape of parterres, fountains, and groves. |

| 1670 | 57 | Designs the gardens at Chantilly for the Grand Condé. |

| 1671 | 58 | Begins work on the gardens at Saint-Germain-en-Laye for Louis XIV. |

| 1680s | 60s – 70s | His fame spreads throughout Europe, and he receives commissions for gardens in Italy, England, and the Netherlands. |

| 1693 | 80 | Retires from his official position at Versailles but continues to advise on garden design. |

| 1700 | 87 | He dies in Paris (September 15th). |

André Le Nôtre (1613-1700) was a renowned French landscape architect who became King Louis XIV’s principal gardener. He masters the French formal garden style, known for its grandeur, symmetry, and meticulous organization.

Here’s a brief overview of his life and career:

- Early Life and Training: Born into a family of gardeners, Le Nôtre learned the trade from his father, the head gardener at the Tuileries Palace. He also studied painting, architecture, and perspective, which influenced his landscape designs.

- Rise to Prominence: Le Nôtre’s career took off in the 1640s when he was commissioned to design the gardens at Vaux-le-Vicomte, an opulent estate owned by Nicolas Fouquet, the superintendent of finances for King Louis XIV. The gardens at Vaux-le-Vicomte were a masterpiece of formal design, featuring intricate parterres, fountains, canals, and statues. Their beauty and grandeur caught the attention of the king, who was so impressed that he appointed Le Nôtre as the chief gardener of the royal gardens.

- Gardener to the King: Impressed by Le Nôtre’s work at Vaux-le-Vicomte, Louis XIV appointed him the chief gardener of the royal gardens. Le Nôtre’s most famous project was transforming the gardens at the Palace of Versailles into a sprawling landscape of breathtaking beauty and grandeur.

- Versailles: At Versailles, Le Nôtre created a series of interconnected gardens, each with its unique theme and atmosphere. He utilized grand avenues, terraces, fountains, sculptures, and meticulously manicured lawns to create a harmonious and visually stunning landscape that reflected the power and majesty of the French monarchy.

- Other Notable Works: Besides Versailles, Le Nôtre designed gardens for numerous other palaces and châteaux throughout France, including Fontainebleau, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, and Chantilly. He also worked on projects in Italy and England, spreading the French formal garden style across Europe.

- Legacy: Le Nôtre’s influence on landscape architecture was immense and far-reaching. His formal gardens became the standard for European landscape design in the 17th and 18th centuries, and his principles of symmetry, order, and grandeur continue to inspire designers today. His work is a testament to the power of human creativity and the ability to shape nature into a work of art.

André Le Nôtre’s work exemplifies the height of French classical garden design. It remains a testament to his artistic vision, technical skill, and ability to create breathtaking landscapes that have stood the test of time.

André Le Nôtre YouTube Video

- Who was André Le Nôtre, the Gardener of King Louis XIV and the Palace of Versailles

- Views: 29,516

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pY5UXtRQIhM

- In Search of André Le Nôtre, Designer of the Tuileries Garden

- Views: 2,933

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=220q6V4fl6U

- André Le Nôtre : le Génie derrière les Jardins à la Française – Documentaire Complet

- Views: 7,631

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IJ_CIIJQ7Vc

- Le Nôtre, un génie français

- Views: 161,194

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=815qYJgsAEM

- André Le Nôtre

- Views: 613

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V48_6PVaGqA

Early Life and Training: Born into a family of gardeners, Le Nôtre learned the trade from his father, the head gardener at the Tuileries Palace. He also studied painting, architecture, and perspective, which influenced his landscape designs.

André Le Nôtre’s upbringing and education laid the groundwork for his extraordinary career as a landscape architect. Born in 1613 into a family deeply rooted in the gardening tradition, he was immersed in horticulture from an early age.

-

- Family of Gardeners: Le Nôtre’s father, Jean Le Nôtre, held the prestigious position of head gardener at the Tuileries Palace in Paris. This royal garden, designed in the Italian Renaissance style, served as young André’s playground and training ground. He grew up surrounded by meticulously manicured parterres, elegant fountains, and statuesque trees, absorbing the principles of formal garden design.

-

-

Apprenticeship: Following his father’s footsteps, Le Nôtre began his apprenticeship as a gardener at the Tuileries Palace. He learned the practical skills of planting, pruning, and maintaining gardens, gaining hands-on experience that would later prove invaluable.

-

Diverse Education: Le Nôtre’s education extended beyond horticulture. He studied painting under Simon Vouet, architecture, and perspective, broadening his artistic and technical knowledge. This multi-disciplinary approach would later shape his unique vision for landscape design, allowing him to integrate art, architecture, and engineering elements into his gardens.

-

Rise to Prominence: Le Nôtre’s career took off in the 1640s when he was commissioned to design the gardens at Vaux-le-Vicomte, an opulent estate owned by Nicolas Fouquet, the superintendent of finances for King Louis XIV. The gardens at Vaux-le-Vicomte were a masterpiece of formal design, featuring intricate parterres, fountains, canals, and statues. Their beauty and grandeur caught the attention of the king, who was so impressed that he appointed Le Nôtre as the chief gardener of the royal gardens.

André Le Nôtre’s rise to prominence is intrinsically linked to his remarkable work at Vaux-le-Vicomte. In the 1640s, Nicolas Fouquet, the ambitious and wealthy Superintendent of Finances for King Louis XIV, commissioned Le Nôtre to design the gardens for his opulent estate. This project would prove to be a turning point in Le Nôtre’s career and a defining moment in the history of landscape architecture.

The gardens at Vaux-le-Vicomte were a testament to Le Nôtre’s genius and his mastery of the French formal garden style. The expansive grounds featured:

-

Intricate Parterres: Elaborate and colorful flower beds arranged in geometric patterns, often incorporating topiary and low hedges.

-

Monumental Fountains: Imposing fountains with cascading water and sculptural elements symbolizes the power and wealth of the owner.

-

Grand Canals: Long, straight canals that reflected the sky and added a sense of grandeur to the landscape.

-

Statues and Sculptures: Carefully placed statues and sculptures adorned the gardens, adding artistic flourishes and mythological references.

-

Optical Illusions: Le Nôtre cleverly used perspective and optical illusions to create an impression of endless space and depth, making the gardens appear even larger and more impressive.

The gardens at Vaux-le-Vicomte were not just aesthetically pleasing; they were also designed for entertainment and social gatherings. Wide avenues provided space for promenades, while hidden groves and secluded corners offered opportunities for private conversations.

The sheer beauty and grandeur of Vaux-le-Vicomte caught the attention of King Louis XIV, who was reportedly envious of Fouquet’s magnificent estate. When Fouquet fell from grace and was imprisoned for alleged financial improprieties, Louis XIV seized the opportunity to hire Le Nôtre as his chief gardener. This marked the beginning of Le Nôtre’s long and illustrious career as the royal gardener, during which he would create some of the most iconic gardens in the world, including the Gardens of Versailles.

Gardener to the King: Impressed by Le Nôtre’s work at Vaux-le-Vicomte, Louis XIV appointed him the chief gardener of the royal gardens. Le Nôtre’s most famous project was transforming the gardens at the Palace of Versailles into a sprawling landscape of breathtaking beauty and grandeur.

The gardens of Vaux-le-Vicomte, with their intricate parterres, majestic fountains, and grand canals, captivated King Louis XIV. So impressed was he with André Le Nôtre’s work that he promptly appointed him as the chief gardener of the royal gardens.

This appointment opened the door for Le Nôtre’s most ambitious and renowned project – the transformation of the gardens at the Palace of Versailles.

Over several decades, Le Nôtre meticulously designed and crafted a landscape that reflected the power, glory, and artistic aspirations of the Sun King and his court.

The gardens of Versailles became an extension of the palace itself, a sprawling canvas on which Le Nôtre painted a masterpiece of formal garden design. He utilized a vast array of elements to create a harmonious and visually stunning landscape:

-

-

Grand Perspective: Le Nôtre created a central axis that extended from the palace, creating a seemingly endless vista of meticulously manicured lawns, ornamental ponds, and statues. This grand perspective emphasized the king’s power and the vastness of his domain.

-

Orangerie: Le Nôtre designed an impressive Orangerie, which housed orange trees and other exotic plants during winter. This showcased the king’s wealth and ability to cultivate rare and delicate species.

-

-

- Fountains and Water Features: Elaborate fountains, cascades, and canals were integrated into the design, adding movement, sound, and visual interest to the landscape. These water features, often adorned with mythological figures and allegories, symbolized the king’s control over nature.

-

- Parterres and Bosquets: Intricate parterres, or ornamental flower beds, were arranged in geometric patterns, creating a tapestry of colors and textures. Hidden within the gardens were bosquets, or small wooded areas, each with its unique theme and atmosphere. These bosquets offered secluded spaces for intimate conversations and romantic encounters.

-

- Statuary and Sculptures: Classical statues and sculptures were strategically placed throughout the gardens, adding artistic flourishes and mythological references. These artworks not only adorned the landscape but also served as symbols of power, virtue, and the ideals of the French monarchy.

Under Le Nôtre’s guidance, the Gardens of Versailles became a stage for courtly life, hosting lavish parties, theatrical performances, and grand processions. They symbolized French artistic and cultural achievement, a testament to a king’s vision and a landscape architect’s genius.

Versailles: At Versailles, Le Nôtre created a series of interconnected gardens, each with its unique theme and atmosphere. He utilized grand avenues, terraces, fountains, sculptures, and meticulously manicured lawns to create a harmonious and visually stunning landscape that reflected the power and majesty of the French monarchy.

Plan view of the Gardens of Versailles (Wiki Image).

Plan view of the Gardens of Versailles (Wiki Image).

André Le Nôtre’s transformation of the gardens at the Palace of Versailles is his most monumental achievement and a testament to his genius as a landscape architect. He crafted a vast and intricate network of gardens, each with a distinct character and purpose, all working together to create a harmonious and awe-inspiring whole.

Key elements of Le Nôtre’s design at Versailles:

-

Grande Perspective: The central axis of the gardens, stretching from the palace to the horizon, created a sense of grandeur and power. This vista, lined with manicured lawns, ornamental ponds, and statues, emphasized the king’s dominion over nature and central position in the universe.

-

Parterres: Elaborate and colorful flower beds, known as parterres, were arranged in geometric patterns, creating a tapestry of intricate designs. These parterres, often incorporating topiary and low hedges, added a touch of whimsy and artistry to the formal landscape.

-

Fountains: Majestic fountains, such as the Latona and the Apollo Fountain, were strategically placed throughout the gardens. Their cascading water and allegorical sculptures added movement, sound, and symbolic meaning to the landscape.

-

Bosquets: Tucked away within the gardens were bosquets, or small wooded areas, each with its unique theme and atmosphere. These intimate spaces provided a respite from the grandeur of the main gardens and offered secluded spots for contemplation and conversation.

-

Terraces: Le Nôtre utilized terraces to create different garden levels and perspectives. The terraces, often adorned with balustrades, statues, and cascading water features, added visual interest and complexity to the landscape.

-

Grand Canal: A massive canal stretched through the gardens, reflecting the sky and providing a picturesque backdrop for boating parties and other festivities. The canal also served a practical purpose, helping to drain the marshy land surrounding the palace.

Le Nôtre’s design at Versailles was not merely about aesthetic beauty; it also reflected the social and political climate of the time. The gardens symbolized the absolute monarchy, showcasing the king’s power and control over nature. They were also a stage for courtly life, hosting lavish parties, theatrical performances, and grand processions.

The Gardens of Versailles remain a testament to Le Nôtre’s genius and ability to create a landscape that is both a work of art and a reflection of the values and aspirations of a bygone era.

Other Notable Works: Besides Versailles, Le Nôtre designed gardens for numerous other palaces and chateaux throughout France, including Fontainebleau, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, and Chantilly. He also worked on projects in Italy and England, spreading the French formal garden style across Europe.

André Le Nôtre’s genius extended beyond Versailles. He left his mark on numerous other gardens across France and Europe, each showcasing his signature style and innovative approach to landscape design.

-

- Fontainebleau: Le Nôtre redesigned the gardens at the Château de Fontainebleau, a former royal residence southeast of Paris. He introduced the “Grand Parterre,” a vast expanse of lawn and flowerbeds surrounded by a canal, and added a series of fountains and sculptures to enhance the landscape.

-

- Saint-Germain-en-Laye: Le Nôtre created a terraced garden overlooking the Seine River at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, another royal residence. The garden features a grand staircase, fountains, and parterres descending towards the river.

-

- Chantilly: At the Château de Chantilly, Le Nôtre designed a complex network of gardens, including the Grand Canal, the Anglo-Chinese garden, and the English garden. These diverse gardens showcased Le Nôtre’s versatility and ability to adapt his style to different landscapes and tastes.

-

Greenwich Park (England): Le Nôtre’s influence extended beyond France. He consulted on the design of Greenwich Park in London, introducing elements of the French formal garden style to the English landscape.

-

Racconigi Castle (Italy): In Italy, Le Nôtre’s expertise was sought for the gardens of Racconigi Castle near Turin. He designed a grand parterre, a large pond, and a series of avenues that radiated from the castle, showcasing his signature geometric style.

These examples highlight Le Nôtre’s prolific career and ability to create stunning gardens that complemented the architecture of palaces and chateaux while also providing spaces for leisure, entertainment, and contemplation. His work left an enduring legacy on landscape architecture, shaping how gardens were designed and appreciated across Europe.

Legacy: Le Nôtre’s influence on landscape architecture was immense and far-reaching. His formal gardens became the standard for European landscape design in the 17th and 18th centuries, and his principles of symmetry, order, and grandeur continue to inspire designers today. His work is a testament to the power of human creativity and the ability to shape nature into a work of art.

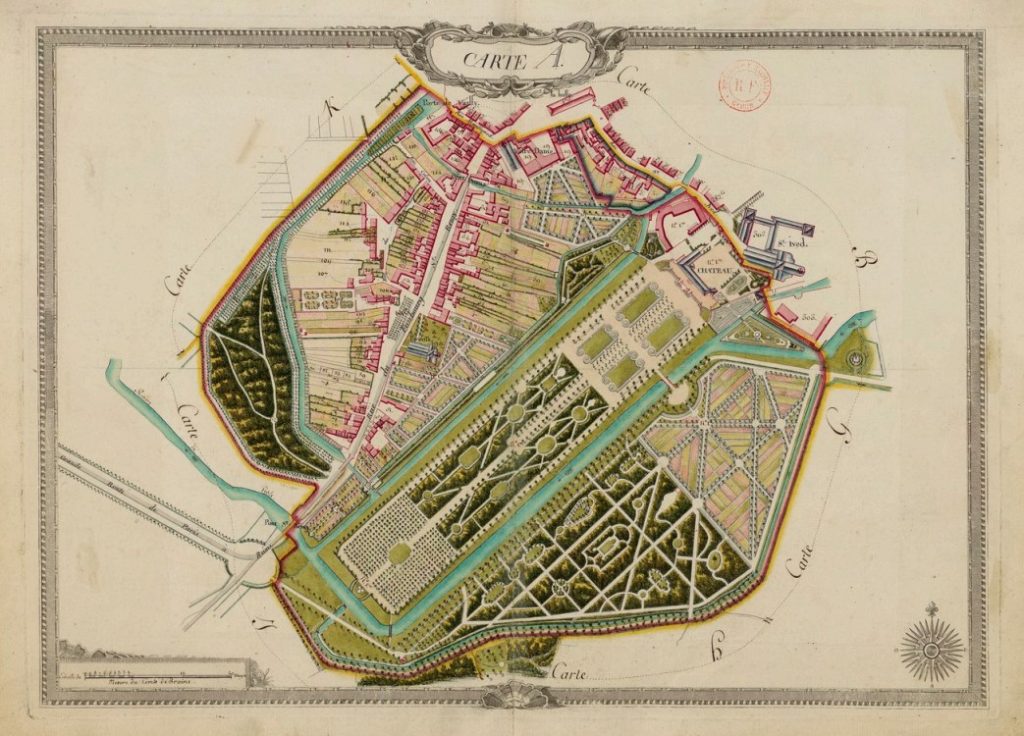

Plan of the Château de Braine and its gardens (Wiki Image).

Absolutely! André Le Nôtre’s impact on landscape architecture is undeniable and still felt today.

Here’s a summary of his lasting legacy:

- Establishing the Standard: For over a century, Le Nôtre’s gardens, especially the Gardens of Versailles, became the epitome of European landscape design. His signature style, characterized by geometric precision, grand axes, and opulent water features, was widely imitated across Europe.

- Inspiring Generations: Le Nôtre’s work has influenced countless landscape architects and designers, from his contemporaries to modern practitioners. His symmetry, order, and perspective principles continue to be studied and applied in contemporary landscape design.

- Creating Timeless Masterpieces: Le Nôtre’s gardens are not just historical artifacts; they are living works of art that continue to inspire and delight visitors today. The Gardens of Versailles, Vaux-le-Vicomte, and other Le Nôtre creations remain popular destinations for tourists and a source of inspiration for garden enthusiasts.

- Influence on Urban Planning: Le Nôtre’s ideas about grand avenues and vistas also influenced urban planning, as seen in the layout of cities like Washington, D.C.

- Symbol of Human Ingenuity: Le Nôtre’s gardens showcase the power of human creativity and the ability to transform nature into a harmonious and aesthetically pleasing environment. They are a testament to humans’ potential to create beauty and order in the world.

In conclusion, André Le Nôtre’s legacy is enduring influence and artistic achievement. His gardens stand as a testament to the power of human creativity and the enduring appeal of formal landscape design.

Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown History

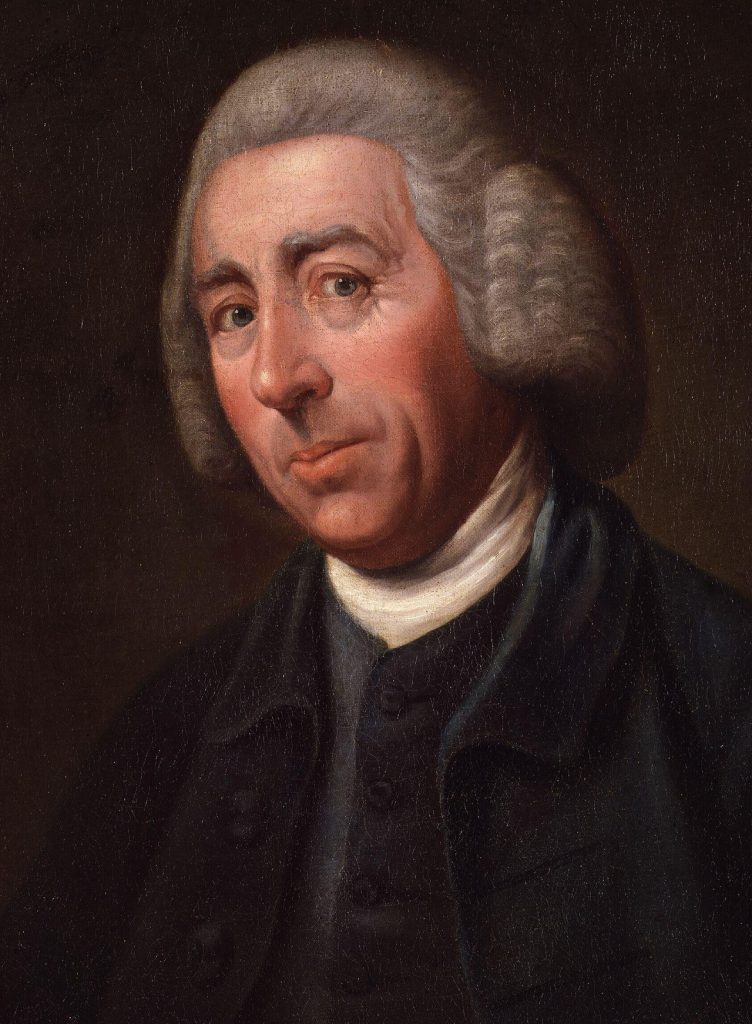

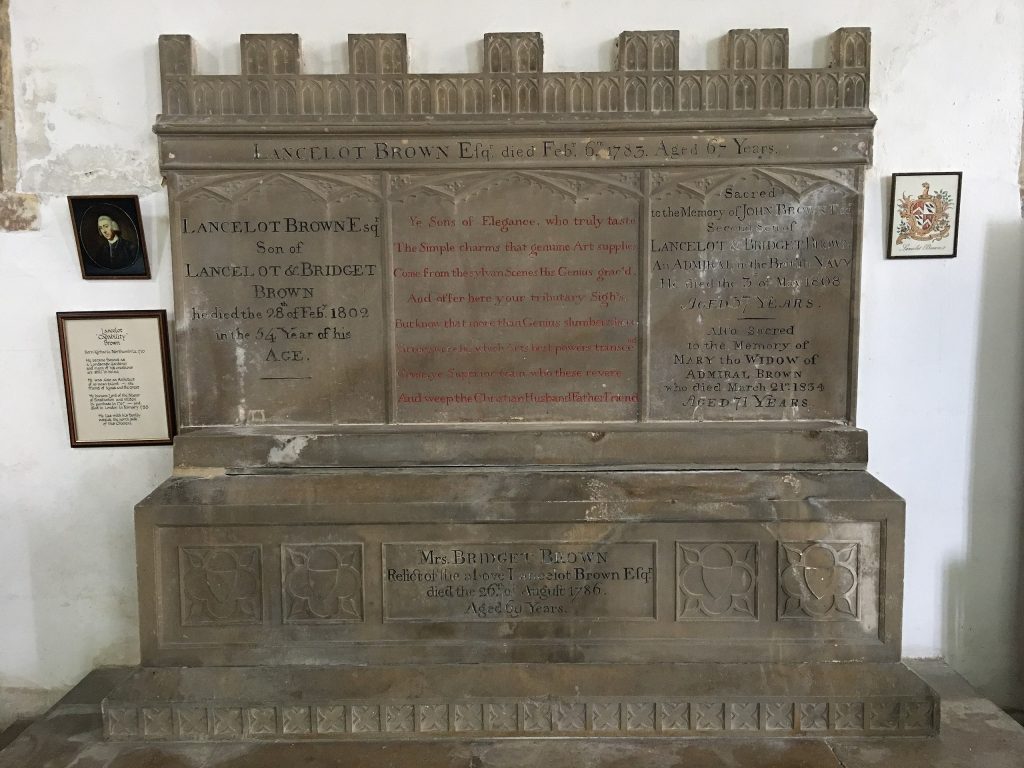

A portrait painting of Brown by Nathaniel Dance, c. 1773 (Wiki Image).

Here are ten notable quotes attributed to Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown or about his work:

- “Nature abhors a straight line.” – Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown

- “I make the whole country look like a garden.” – Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown

- “Consult the genius of the place in all.” – Alexander Pope, often quoted by Brown to emphasize his approach to landscape design.

- “I want my work to appear as if it were the hand of God.” – Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown

- “Wealthy landowners are my clients, but it is nature that is my master.” – Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown

- “Landscape is the work of a thousand years.” – Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown

- “Gardening is the purest of human pleasures.” – Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown

- “My landscapes are living paintings.” – Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown

- “A garden must combine the poetic and the mysterious with a feeling of serenity and joy.” – Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown

- “The art of landscaping is to conceal art and make everything appear natural.” – Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown

| Year | Age | Events, Projects & Patrons | Key Features & Style |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1716 | 0 | Born in Kirkharle, Northumberland, England (August 30th, baptized). | |

| 1740 | 24 | Begins work as a gardener at Kirkharle Hall. | |

| 1741 | 25 | Moves to Stowe, Buckinghamshire, to work under William Kent, a leading landscape designer. | – Gains experience in the development of the English landscape garden style. |

| 1751 | 35 | Establishes his own independent practice. <br> – Croome Court, Worcestershire (for the 6th Earl of Coventry): One of his first major commissions. | – Creates a naturalistic landscape with a serpentine lake, sweeping lawns, and clumps of trees. <br> – Begins to develop his signature “Capability” style. |

| 1750s | 30s-40s | – Petworth House, West Sussex (for the 2nd Earl of Egremont) <br> – Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire (for the 4th Duke of Marlborough) <br> – Chatsworth House, Derbyshire (for the 4th Duke of Devonshire) | – Re-shapes landscapes on a grand scale, creating expansive lawns, lakes, and tree clumps. <br> – Removes formal gardens and geometric layouts in favor of a more natural aesthetic. |

| 1764 | 48 | King George III appointed Master Gardener at Hampton Court Palace. | – Royal recognition of his talent and influence. |

| 1760s – 1770s | 40s-50s | – Bowood House, Wiltshire (for the 1st Marquess of Lansdowne) <br> – Longleat, Wiltshire (for the 1st Marquess of Bath) <br> – Alnwick Castle, Northumberland (for the 1st Duke of Northumberland) | – Continues to receive numerous commissions from wealthy landowners. <br> – Refines his “Capability” style, creating harmonious landscapes that appear natural but are carefully designed. |

| 1783 | 67 | Dies in London (February 6th). |

Lancelot “Capability” Brown (1716-1783) was an influential English landscape architect renowned for pioneering the English landscape garden style.

Early Life and Career:

- Humble Beginnings: Brown was born in Northumberland, England, and started his career as a gardener’s apprentice. He honed his skills and knowledge while working for prominent figures like Sir William Loraine and Lord Cobham at Stowe.

- The Nickname: Brown earned the nickname “Capability” for his habit of assessing a property and telling clients about its “capabilities” for improvement. This knack for identifying potential and transforming landscapes into idyllic scenes became his hallmark.

Rise to Prominence:

- Stowe Gardens: Brown’s work at Stowe under the guidance of William Kent, a leading garden designer of the time, exposed him to the emerging English landscape style. He learned to appreciate the beauty of natural forms and integrate them into his designs.

- Independent Career: In 1751, Brown left Stowe to establish his practice as a landscape architect. His reputation quickly grew, and he soon became one of the most sought-after designers in England.

- Royal Patronage: Brown’s success attracted the attention of the aristocracy and even royalty. He designed gardens for many prominent figures, including King George III.

Design Philosophy and Style:

- Naturalistic Aesthetic: Brown’s designs were characterized by a naturalistic aesthetic that sought to emulate nature’s beauty. He rejected the rigid formality of earlier garden styles, opting instead for sweeping lawns, meandering lakes, and clumps of trees that appeared to have grown organically.

- Ha-Ha: One of Brown’s signature elements was the “ha-ha,” a sunken ditch that created an invisible boundary between the garden and the surrounding landscape, allowing for uninterrupted views.

- Landscapes as Paintings: Brown viewed landscapes as living paintings, carefully composing vistas and incorporating elements like follies, bridges, and temples to enhance the scenery.

Legacy:

- Widespread Influence: Brown’s naturalistic style revolutionized English landscape design and profoundly impacted garden design worldwide. His work can be seen in numerous estates and parks across England and beyond.

- Controversial Figure: Brown’s approach was not without its critics. Some accused him of destroying earlier formal gardens to create his landscapes, while others praised him for his innovative vision.

Lancelot “Capability” Brown’s enduring legacy is a testament to his creative genius and ability to transform the English landscape into a work of art. His designs inspire and delight visitors today, and his influence can be seen in countless parks and gardens worldwide.

Lancelot “Capability” Brown YouTube Video

- England’s Greatest Garden Designer – Capability Brown

- Views: 20,226

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VcwhvJc-sSk

- Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown and the English Estate Landscape

- Views: 526

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2y0KRtLn0kY

- Was Lancelot Capability Brown a great landscape designer?

- Views: 8,787

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r6xt3xxQQaQ

- Creating a Garden of Eden, Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown

- Views: 4,924

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2LSGdCtBVYU

- Prince Charles visits the birthplace of Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown

- Views: 5,433

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5GDoWAPCLUU

Humble Beginnings: Lancelot Brown was born in Northumberland, England, and started his career as a gardener’s apprentice. He honed his skills and knowledge while working for prominent figures like Sir William Loraine and Lord Cobham at Stowe.

Lancelot “Capability” Brown’s journey to becoming a renowned landscape architect began with humble origins. He was born in 1716 in the village of Kirkharle, Northumberland, England.

-

-

Early Years: Brown’s family had modest means. His father was a land agent and his mother worked as a housekeeper at Kirkharle Hall. Young Lancelot received a basic education at the village school, but his true passion lay in the outdoors and the natural world.

-

Gardener’s Apprentice: At 16, Brown began his career as a gardener’s apprentice at Kirkharle Hall under the tutelage of the head gardener. Here, he began to develop his skills in horticulture and landscaping, learning the practical aspects of plant cultivation, pruning, and garden maintenance.

-

Move to Stowe: In 1739, Brown left Kirkharle and moved south to Stowe, Buckinghamshire, where he found employment as an under-gardener on Lord Cobham’s estate. Stowe was a hub of landscape innovation, where leading figures like William Kent experimented with new approaches to garden design.

-

-

Working with William Kent: Brown’s time at Stowe proved pivotal in his development as a landscape architect. He worked closely with William Kent, a prominent designer who established the English landscape garden style. Kent’s naturalistic approach, emphasizing the beauty of rolling hills, serpentine lakes, and clumps of trees, resonated with Brown and influenced his design philosophy.

-

Rising through the Ranks: Brown’s talent and dedication did not go unnoticed. He quickly rose to Stowe’s ranks, eventually becoming head gardener in 1741. In this role, he oversaw the maintenance and development of the gardens, working on various projects that further honed his skills and artistic vision.

Brown’s early experiences as a gardener’s apprentice and his exposure to the innovative landscape designs at Stowe laid the foundation for his remarkable career. During this formative period, he developed his unique approach to landscape architecture, which would later revolutionize the field and earn him the nickname “Capability.”

The Nickname: Lancelot Brown earned the nickname “Capability” for his habit of assessing a property and telling clients about its “capabilities” for improvement. This knack for identifying potential and transforming landscapes into idyllic scenes became his hallmark.

The nickname “Capability” Brown is synonymous with the renowned landscape architect Lancelot Brown. It originated from his unique approach to assessing a property’s potential. When Brown would visit a potential client’s estate, he would assess the land, taking note of its natural features, topography, and existing vegetation. He would then enthusiastically point out the “capabilities” of the land, outlining how it could be transformed into a picturesque and harmonious landscape.

Brown’s ability to envision the hidden potential in seemingly ordinary landscapes and his eloquence in conveying his ideas to clients earned him the nickname “Capability.” This moniker stuck, and he eventually became known as “Capability” Brown throughout England and beyond.

His approach was a departure from the formal, geometric gardens that were popular at the time. Instead of imposing rigid designs on the land, Brown sought to work with nature, enhancing its inherent beauty and creating natural and effortless landscapes.

This ability to see a landscape’s “capabilities” and transform it into an idyllic scene became Brown’s hallmark. His clients were often amazed by his vision and the transformations he achieved, turning ordinary fields and meadows into breathtaking vistas that seamlessly blended with the surrounding countryside.

Brown’s nickname, “Capability,” is a testament to his creative vision, persuasive skills, and ability to unlock the hidden potential of the natural world. It is a name that has become synonymous with the English landscape garden style and the enduring legacy of one of the most influential landscape architects.

Stowe Gardens: Lancelot Brown’s work at Stowe under the guidance of William Kent, a leading garden designer of the time, exposed him to the emerging English landscape style. He learned to appreciate the beauty of natural forms and integrate them into his designs.

Stowe Gardens, a sprawling estate in Buckinghamshire, England, played a pivotal role in Lancelot “Capability” Brown’s development as a landscape architect. Under the guidance of William Kent, a leading figure in English garden design, Brown was exposed to the emerging English landscape style.

Kent, known for his naturalistic approach to landscape design, rejected the rigid formality of earlier garden styles in favor of creating landscapes that appeared to be natural yet were carefully planned and executed. He sought to evoke a sense of harmony and tranquility by incorporating rolling hills, serpentine lakes, and clumps of trees into his designs.

Kent’s philosophy and techniques deeply influenced Brown, who began his career at Stowe as an under-gardener. He learned to appreciate natural forms’ beauty and integrate them into his designs. Brown’s work at Stowe involved maintaining the existing gardens and contributing to their ongoing development. He worked on various projects, including creating the Grecian Valley, a sweeping landscape that exemplified the English landscape style.

Brown’s experience at Stowe was a formative period in his career. Here, he honed his skills, developed his artistic vision, and made valuable connections with influential figures in landscape architecture. His time at Stowe laid the groundwork for his future success as one of history’s most celebrated landscape architects.

Independent Career: In 1751, Lancelot Brown left Stowe to establish his practice as a landscape architect. His reputation quickly grew, and he soon became one of the most sought-after designers in England.

In 1751, Lancelot “Capability” Brown took a bold step, leaving his secure position at Stowe to establish his independent practice as a landscape architect. This decision proved to be a turning point in his career, propelling him to national prominence and transforming the landscape of England.

Brown’s reputation grew rapidly, fueled by his innovative designs, charismatic personality, and ability to connect with his aristocratic clientele. He quickly became the go-to landscape architect for the wealthy and influential, transforming their estates into picturesque havens that embodied the English landscape style.

Some of his most notable projects during this period include:

-

- Croome Court: Brown’s first major independent commission was for the Earl of Coventry at Croome Court in Worcestershire. He redesigned the parkland, creating a serpentine lake, meandering paths, and carefully placed clumps of trees.

-

- Blenheim Palace: Brown’s work at Blenheim Palace, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is considered one of his masterpieces. He transformed the formal gardens into a vast landscape park, incorporating a lake, a bridge, and a cascade.

- Chatsworth House: Another iconic project, Brown redesigned the parkland at Chatsworth House, creating a picturesque landscape that harmonized with the natural beauty of the surrounding Derbyshire countryside.

Brown’s success was not without controversy. Some critics accused him of destroying existing formal gardens to create his landscapes. In contrast, others praised him for his innovative vision and ability to create beautiful and functional spaces.

Despite the criticism, Brown’s popularity continued to soar. His client list included some of the most prominent figures in England, including royal family members. He became known as the “landscape gardener of England,” his designs set the standard for landscape architecture for future generations.

Royal Patronage: Lancelot Brown’s success attracted the aristocracy’s and even royalty’s attention. He designed gardens for many prominent figures, including King George III.

Lancelot “Capability” Brown’s innovative and naturalistic approach to landscape design quickly earned him a reputation as one of England’s most sought-after landscape architects. His success attracted the attention of the aristocracy, who commissioned him to transform their estates into picturesque landscapes.

Brown’s fame soon reached the ears of the royal family. King George III, who had a keen interest in agriculture and landscaping, was particularly impressed with Brown’s work. In 1764, he appointed Brown as his Royal Gardener at Hampton Court Palace, a position that further elevated Brown’s status and influence.

Under royal patronage, Brown’s career reached new heights. He was commissioned to design gardens and landscapes for numerous royal residences, including:

- Hampton Court Palace: Brown redesigned the gardens, creating a more naturalistic landscape with sweeping lawns, a serpentine lake, and clumps of trees.

- Kew Gardens: Brown was involved in the early development of Kew Gardens, which would later become one of the world’s most renowned botanical gardens.

- Buckingham Palace: Although Brown’s work at Buckingham Palace was later altered, he initially transformed the grounds into a landscape park with a lake and a variety of trees and shrubs.

Brown’s work for the royal family solidified his position as the leading landscape architect of his time. His royal patronage also opened doors for him to work on numerous other prestigious projects for the aristocracy, further cementing his legacy as one of the most influential figures in the history of landscape design.

Naturalistic Aesthetic: Lancelot Brown’s designs were characterized by a naturalistic aesthetic that sought to emulate nature’s beauty. He rejected the rigid formality of earlier garden styles, opting instead for sweeping lawns, meandering lakes, and clumps of trees that appeared to have grown organically.

Lancelot “Capability” Brown’s naturalistic aesthetic was a revolutionary departure from the formal gardens that dominated the European landscape in the 17th and early 18th centuries. He eschewed the rigid symmetry, geometric patterns, and manicured topiaries of French and Dutch gardens, opting instead for a more organic and flowing design that sought to mimic the beauty of the natural world.

Brown’s signature elements included:

-

Sweeping Lawns: Vast expanses of lawn that are gently rolled and curved, creating a sense of open space and freedom. These lawns were often dotted with strategically placed trees to provide shade and visual interest.

-

Serpentine Lakes: Meandering lakes and ponds that reflect the sky and the surrounding landscape, adding a sense of tranquility and depth to the garden. These water features were often created by damming existing streams or rivers, blurring the line between man-made and natural elements.

-

Clumps of Trees: Carefully positioned groups of trees, known as clumps, that appeared to have grown naturally in the landscape. These clumps provided visual interest, shade, and a sense of enclosure, while also creating a more varied and naturalistic landscape.

-

Hidden Ha-has: Sunken ditches, known as ha-has, created invisible boundaries between the garden and the surrounding landscape. This allowed for uninterrupted views and a seamless integration of the garden with the wider countryside.

Brown’s naturalistic aesthetic was inspired by the English landscape, which he sought to idealize and romanticize in his designs. His gardens were meant to evoke a sense of tranquility, harmony, and emotional connection with nature.

While Brown’s work was not without its critics, who accused him of destroying existing formal gardens, his influence on landscape design was immense and lasting. His naturalistic style became the dominant trend in English gardening, and his ideas continue to inspire landscape architects and garden enthusiasts worldwide.

Ha-Ha: One of Lancelot Brown’s signature elements was the “ha-ha,” a sunken ditch that created an invisible boundary between the garden and the surrounding landscape, allowing for uninterrupted views.

The ha-ha was a clever innovation introduced to English gardens by Lancelot “Capability” Brown. It is a sunken ditch with a retaining wall on the garden side, designed to create a visual and physical barrier for livestock while preserving an uninterrupted landscape view.

The ha-ha’s name is believed to have originated from the surprised exclamation (“Ha ha!”) uttered by visitors when they unexpectedly encountered the hidden ditch.

Key features and benefits of the ha-ha:

-

- Uninterrupted Views: The ha-ha allowed seamless transitions between the garden and the surrounding landscape, creating an illusion of boundless space. This enhanced the sense of natural beauty and allowed for picturesque countryside views.

-

-

Invisible Boundary: The sunken design of the ha-ha made it virtually invisible from a distance, especially when viewed from the higher elevation of the garden. This allowed for a sense of continuity between the cultivated garden and the wilder landscape beyond.

-

Practical Function: The ha-ha served a practical purpose by preventing livestock from entering the garden while allowing for grazing animals to maintain the surrounding parkland. This eliminated the need for fences or walls, which would have interrupted the views and disrupted the natural flow of the landscape.

-

The ha-ha became a hallmark of the English landscape garden style and was widely adopted by other landscape architects and garden designers. Its innovative design and practical functionality made it popular in many estates and parks across England and beyond.

The ha-ha’s legacy extends beyond its practical use. It represents a shift in attitudes towards landscape design, emphasizing the integration of the garden with the natural world and creating a more harmonious and visually pleasing environment.

Landscapes as Paintings: Lancelot Brown viewed landscapes as living paintings, carefully composing vistas and incorporating elements like follies, bridges, and temples to enhance the scenery.

Lancelot “Capability” Brown possessed a unique artistic vision. He viewed landscapes as living paintings that could be shaped and molded to create picturesque scenes. He carefully composed vistas, considering elements like light, shadow, color, and texture, just as a painter would compose a canvas.

To enhance the scenery, Brown incorporated various architectural and ornamental elements into his landscapes:

-

Follies: These whimsical structures, such as mock ruins, towers, or grottoes, were strategically placed to add interest and intrigue to the landscape. They served as focal points, drawing the eye and inviting exploration.

-

Bridges: Brown often incorporated bridges into his designs for their practical function and as aesthetic elements. Graceful arched or rustic wooden bridges added a touch of elegance and charm to the landscape while providing opportunities for scenic views.

-

Temples: Classical temples or other architectural structures were sometimes included in Brown’s landscapes to evoke a sense of history or mythology or simply to provide a striking visual contrast to the natural surroundings.

Brown’s approach to landscape design was not simply about creating beautiful scenery but crafting an emotional experience for the viewer. Through his carefully composed landscapes, he sought to evoke feelings of tranquility, awe, and wonder.

By integrating architectural elements and carefully framing views, Brown transformed his landscapes into living works of art. His approach was highly influential and inspires landscape architects and garden designers today.

Widespread Influence: Lancelot Brown’s naturalistic style revolutionized English landscape design and profoundly impacted garden design worldwide. His work can be seen in numerous estates and parks across England and beyond.

Lancelot “Capability” Brown’s influence on landscape design extended far beyond his lifetime and the borders of England. His naturalistic style, which emphasized the integration of gardens with the natural landscape, revolutionized how people perceived and interacted with outdoor spaces.

Brown’s widespread influence can be attributed to several factors:

-

- Rejection of Formality: Brown rejected the rigid formality of earlier garden styles, such as the French and Dutch gardens, characterized by geometric patterns, straight lines, and manicured topiaries. He favored a more organic and flowing design that sought to mimic the natural world.

- Emphasis on Natural Beauty: Brown’s designs celebrated the inherent beauty of the English countryside, incorporating rolling hills, serpentine lakes, and clumps of trees into his landscapes. He believed gardens should be an extension of nature, seamlessly blending with the surrounding environment.

- Adaptability: Brown’s style was adaptable to different settings and scales. He designed landscapes for a wide range of clients, from wealthy landowners to royalty, creating unique and tailored designs that responded to the specific characteristics of each site.

- Popularity and Patronage: Brown’s work was immensely popular among the English aristocracy and gentry, who sought to emulate his naturalistic style on their estates. His royal patronage further solidified his reputation and influence, leading to numerous commissions throughout England.

The impact of Brown’s work can be seen in numerous estates and parks across England, including:

- Croome Court: One of Brown’s earliest commissions, where he transformed the grounds into a naturalistic landscape with a serpentine lake.

- Blenheim Palace is Brown’s masterpiece. He created a vast landscape park that seamlessly integrated with the surrounding countryside.

- Prior Park: A Palladian mansion with extensive gardens designed by Brown, featuring a picturesque lake and a Palladian bridge.

- Stowe Landscape Garden: Brown worked on the gardens at Stowe under William Kent, where he honed his skills and developed his naturalistic style.

Brown’s influence extended beyond England, inspiring landscape architects and garden designers in other countries, including the United States. His ideas about natural beauty, harmony with the environment, and the importance of creating spaces for relaxation and contemplation resonated with people worldwide, and his legacy continues to shape our understanding of landscape design today.

Controversial Figure: Lancelot Brown’s approach was not without its critics. Some accused him of destroying earlier formal gardens to create his landscapes, while others praised him for his innovative vision.

Memorial to Capability Brown in the St Peter and St Paul church, Fenstanton, Cambridgeshire (Wiki Image).

Lancelot “Capability” Brown was a controversial figure in his time, and his legacy remains a debate among landscape historians and enthusiasts.

Criticisms:

- Destruction of Formal Gardens: Brown often removed or altered existing formal gardens to create his signature naturalistic landscapes. This led to the loss of many historic garden features and designs, which some critics viewed as cultural vandalism.

- Uniformity: Brown’s critics argued that his style lacked variety and imagination, creating landscapes that looked too similar across different properties. They felt that his sweeping lawns, clumps of trees, and meandering lakes became repetitive and predictable.

- Artificiality: While Brown aimed to create natural landscapes, some argued that his designs were highly artificial and manipulated, with nature carefully sculpted to conform to his aesthetic vision.

Praise:

- Innovative Vision: Despite the criticisms, Brown was praised for his creative approach to landscape design. He broke away from the rigid formality of earlier styles, introducing a more naturalistic aesthetic that celebrated the beauty of the English countryside.

- Picturesque Landscapes: Brown’s landscapes were considered picturesque, evoking a sense of tranquility and harmony with nature. His use of light, shadow, and water created visually stunning scenes that captured visitors’ imaginations.

- Influence on Landscape Design: Brown’s work profoundly impacted landscape design in England, Europe, and America. His naturalistic style became the dominant trend in the 18th and 19th centuries, and his influence can still be seen in many parks and gardens today.

Lancelot “Capability” Brown remains a complex and controversial figure in the history of landscape architecture. While his work was not without its detractors, his innovative vision and lasting impact on landscape design cannot be denied.

Frederick Law Olmsted History

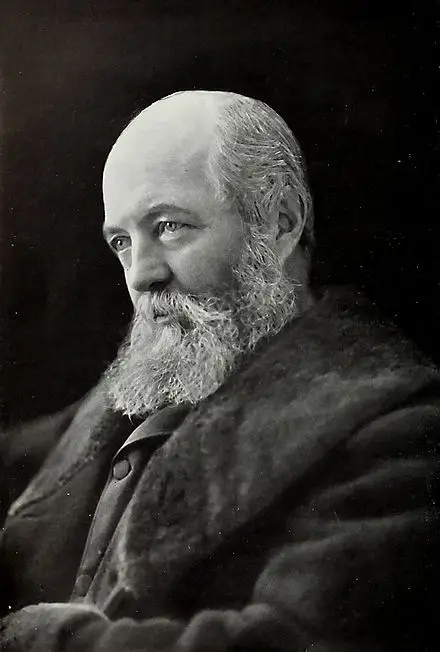

Olmsted in 1893; engraving after a photograph (Wiki Image).

“A park is a work of art, designed to produce certain effects upon the mind of men.”

“The enjoyment of scenery employs the mind without fatigue and yet exercises it; tranquilizes it and yet enlivens it; and thus, through the influence of the mind over the body, gives the effect of refreshing rest and reinvigoration to the whole system.”

“The beauty of the park should be the beauty of the fields, the meadow, the prairie, of the green pastures, and the still waters.”

“Cities are for traffic; parks are for rest and contemplation.”

“What we want to gain is tranquility and rest to the mind.”

“The park should, as far as possible, complement the town. Openness is the one thing you cannot get in buildings.”

“I have all my life been considering distant effects and always sacrificing immediate success and applause to that of the future.”

“The main object and justification [of a park] is simply to produce a certain influence in the minds of people and through this to make life in the city healthier and happier.”

“A park ought to have the aspect of a place where people would want to come and stroll about in a quiet and leisurely way.”

“The poorest man in his cottage may have plants and flowers to admire, but he cannot have woods and lawns.”

| Year | Age | Events, Projects & Collaborators | Key Features & Style |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1822 | 0 | Born in Hartford, Connecticut, on April 26th. | |

| 1837 | 15 | Works as an apprentice seaman on a merchant ship to China. | – Early exposure to diverse landscapes and cultures. |

| 1840s | 20s | – Studies scientific agriculture and engineering. <br> – Manages a farm on Staten Island. <br> – Travels extensively in the American South and Europe, writing about social and environmental issues. | – Develops a deep appreciation for nature and its restorative qualities. <br> – Becomes interested in the relationship between landscape and social well-being. |

| 1857 | 35 | – Appointed Superintendent of Central Park in New York City. <br> – Wins the design competition for Central Park with Calvert Vaux. | – Begins his most famous and influential project. <br> – Creates a naturalistic landscape in the city’s heart, offering escape and recreation. |

| 1858 | 36 | – Central Park construction begins. | – Incorporates a variety of landscapes: meadows, woodlands, lakes, and formal gardens. <br> – Designs separate circulation systems for pedestrians, horseback riders, and carriages. |

| 1861-1865 | 39-43 | – Serves as Executive Secretary of the U.S. Sanitary Commission during the Civil War. | – Applies his organizational and planning skills to improve sanitation and medical care for soldiers. |

| 1863 | 41 | – Publishes Yosemite and the Mariposa Grove: A Preliminary Report, advocating for the preservation of Yosemite Valley. | – Early and influential voice in the conservation movement. |

| 1865 | 43 | – Resumes his landscape architecture practice. | |

| 1860s – 1890s | 40s-70s | – Designs numerous parks and public spaces across the United States: <br> – Prospect Park in Brooklyn, New York <br> – The Emerald Necklace in Boston, Massachusetts <br> – Stanford University campus in California <br> – Niagara Reservation in New York <br> – Biltmore Estate in North Carolina | – Develop a comprehensive approach to landscape design, considering social, environmental, and aesthetic factors. <br> – Creates parks that serve various needs: recreation, education, and social interaction. |

| 1895 | 73 | Retires from active practice due to declining health. | |

| 1903 | 81 | Dies in Brookline, Massachusetts (August 28th). |

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) was a visionary American landscape architect, journalist, social critic, and public administrator. He is considered the father of American landscape architecture, having designed some of the most iconic parks and public spaces in the United States.

Early Life and Career:

- Diverse Background: Olmsted had a varied background, working as a farmer, merchant seaman, journalist, and social critic before turning to landscape architecture. His travels and experiences exposed him to different cultures and landscapes, later influencing his designs.

- Central Park Commission: In 1857, Olmsted, along with Calvert Vaux, won the competition to design New York City’s Central Park. This landmark project launched Olmsted’s career as a landscape architect and established his reputation as a visionary designer.

- Prolific Career: Olmsted went on to design numerous other parks and public spaces throughout the United States, including Prospect Park in Brooklyn, the Emerald Necklace in Boston, and the grounds of the U.S. Capitol.

Design Philosophy and Style:

- Park Movement: Olmsted pioneered the park movement, which advocated for creating large public parks in urban areas. He believed parks were essential for city dwellers’ health, well-being, and social interaction.

- Naturalistic Design: Olmsted’s designs emphasized natural beauty and incorporated elements such as meadows, woodlands, lakes, and winding paths to create a sense of escape from the urban environment.

- Social Consciousness: Olmsted’s designs were not just about aesthetics; they also reflected his social conscience and belief in providing public spaces for all members of society, regardless of social class.

Legacy:

- Father of American Landscape Architecture: Olmsted is the father of American landscape architecture, having shaped the field with his innovative designs and influential writings.

- Transformative Impact: His work transformed urban planning in the United States and inspired the creation of public parks in cities worldwide.

- Enduring Legacy: Millions of people enjoy Olmsted’s parks and public spaces today, providing a respite from urban life and a connection to nature.

Frederick Law Olmsted’s legacy is visionary leadership, innovative design, and a deep commitment to social welfare. His work has profoundly impacted how we think about and interact with the natural world in our cities and towns.

Frederick Law Olmsted YouTube Video

- Frederick Law Olmsted | Designing America

- Views: 33,857

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PoiCwkYengM

- Frederick Law Olmsted | Best Planned City in the World | Olmsted, Vaux, and the Buffalo Park System

- Views: 1,609

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xF4dICANPUA

- Frederick Law Olmsted Lecture: Aaron Sachs

- Views: 2,331

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pmzBB_ZjJvw

- Gardens Around the World: Frederick Law Olmsted’s Public Landscape

- Views: 2,217

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UUf_1GIP-GY

- The Bicentennial Celebration of the man behind Americas greatest Parks | Open Studio

- Views: 173

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=adWj2Ow_VoA

Diverse Background: Olmsted had a varied background, working as a farmer, merchant seaman, journalist, and social critic before turning to landscape architecture. His travels and experiences exposed him to different cultures and landscapes, later influencing his designs.

Frederick Law Olmsted’s diverse background shaped his unique perspective and approach to landscape architecture. His experiences in various fields and his exposure to different cultures and environments enriched his understanding of the relationship between humans and nature, ultimately influencing his groundbreaking designs.

Early Life:

-

Farmer: Olmsted was born into a prosperous merchant family in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1822. However, he developed a deep appreciation for nature and agriculture from a young age. He experimented with scientific farming methods on his property, showcasing his early interest in the land and its potential.

-

Merchant Seaman: In his early twenties, Olmsted embarked on a merchant sea voyage to China, exposing him to different cultures and landscapes. This experience broadened his horizons and sparked his interest in travel and exploration.

-

Journalist and Social Critic: Upon his return from China, Olmsted pursued a career in journalism, writing extensively about social and political issues. He traveled through the American South, documenting the horrors of slavery and advocating for its abolition. His keen observations and insightful writing revealed his deep concern for social justice and equality.

Travels and Influences:

-

European Parks: In 1850, Olmsted traveled to Europe, where he was deeply impressed by the public parks he visited, notably Birkenhead Park in England. He admired the park’s design, emphasizing natural beauty and accessibility for all social classes. This experience later inspired his designs for urban parks in the United States.

-

American Landscape: Olmsted’s travels throughout the United States, including his journey through the South, exposed him to his country’s diverse landscapes and cultures. He developed a deep appreciation for America’s natural beauty and the unique character of its different regions.

Olmsted’s varied background and extensive travels gave him a broad perspective and a deep understanding of the complex relationship between humans and the environment. He recognized the importance of nature in urban settings and the need for public spaces that would provide opportunities for recreation, relaxation, and social interaction. This unique combination of experiences and insights shaped his philosophy and approach to landscape architecture, leading him to create some of the world’s most iconic and influential parks.

Central Park Commission: In 1857, Olmsted, along with Calvert Vaux, won the competition to design New York City’s Central Park. This landmark project launched Olmsted’s career as a landscape architect and established his reputation as a visionary designer.

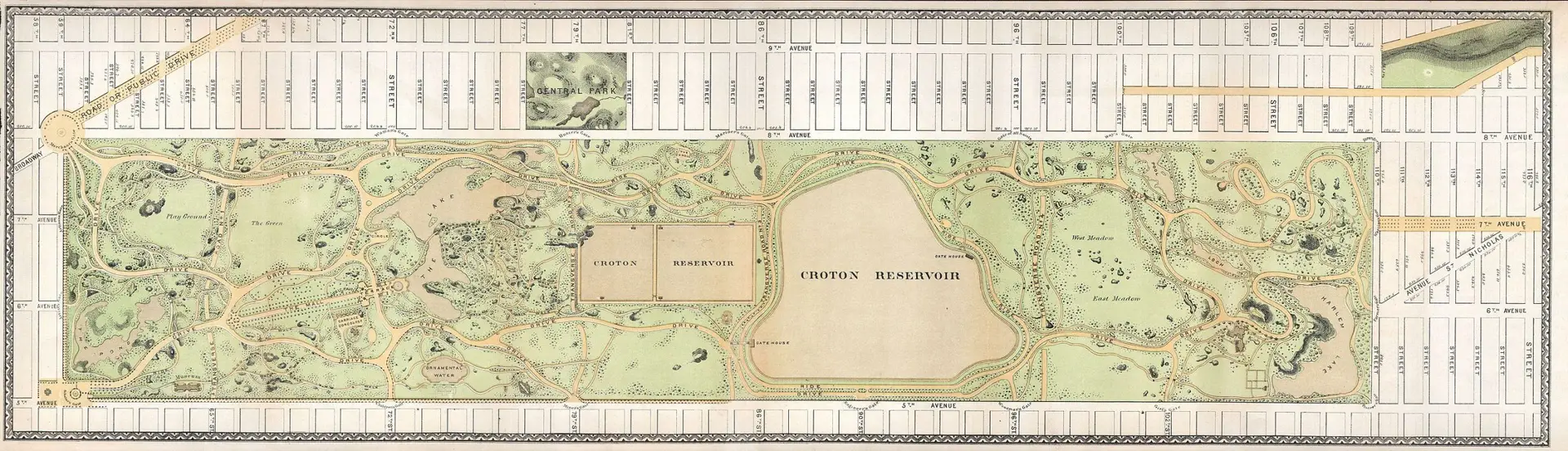

The modified Greensward Plan for the park from 1868 (Wiki Image).

The modified Greensward Plan for the park from 1868 (Wiki Image).

Absolutely! The Central Park Commission was pivotal in Frederick Law Olmsted’s career. In 1857, he and Calvert Vaux, an English-born architect, partnered to submit their “Greensward Plan” for the design of Central Park in New York City. Their vision, which emphasized creating a natural oasis amid a bustling city, won the competition and set the stage for Olmsted’s prominence.

The Greensward Plan:

The Greensward Plan was a radical departure from the formal European-style parks that were popular then. Instead of rigid geometry and ornamental displays, Olmsted and Vaux proposed a more naturalistic design that would offer visitors a variety of landscapes and experiences.

Key features of the Greensward Plan included:

- Separation of Circulation: The plan separated pedestrian paths from carriage drives and transverse roads, creating a peaceful and immersive experience for park-goers.

- Diverse Landscapes: The park was designed to include various natural features, such as meadows, woodlands, lakes, and rocky outcroppings, offering a sense of escape from the urban environment.

- Recreational Opportunities: The plan incorporated ample space for recreational activities, including walking, skating, boating, and picnicking.

- Social Spaces: The design included gathering places like the Mall and Bethesda Terrace, encouraging social interaction and community building.

Impact on Olmsted’s Career:

The Central Park Commission launched Olmsted’s career as a landscape architect and solidified his reputation as a visionary designer. Central Park’s success led to numerous other commissions for parks and public spaces throughout the United States.

Olmsted’s work on Central Park also established him as a leading advocate for the park movement, which sought to create green spaces in urban areas to benefit all citizens. He believed that parks were essential for urban populations’ physical and mental health, and he championed the idea that access to nature should be a right, not a privilege.

The Central Park Commission began Frederick Law Olmsted’s remarkable career. His groundbreaking work on this iconic park not only transformed the landscape of New York City but also paved the way for the development of public parks across the United States and worldwide.

Prolific Career: Olmsted went on to design numerous other parks and public spaces throughout the United States, including Prospect Park in Brooklyn, the Emerald Necklace in Boston, and the grounds of the U.S. Capitol.

Frederick Law Olmsted’s career was prolific. Following his success with Central Park, he went on to design numerous parks and public spaces throughout the United States, leaving an enduring legacy in many cities.

Olmsted’s collaboration with Calvert Vaux continued with the design of Prospect Park in Brooklyn, New York. Completed in 1867, Prospect Park showcases a similar naturalistic style to Central Park, with rolling meadows, wooded areas, and a large lake.

In Boston, Olmsted conceived the Emerald Necklace, a seven-mile chain of parks linked by parkways and waterways. This visionary project transformed the city’s landscape, providing residents with access to green spaces and recreational opportunities.

Olmsted’s influence also extended to Washington, D.C., where he designed the grounds of the U.S. Capitol, creating a landscape that complemented the grandeur of the building while providing a welcoming space for visitors.

Beyond urban parks, Olmsted’s work encompassed a variety of projects, including college campuses, private estates like the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina, and even residential communities. His commitment to creating functional and aesthetically pleasing spaces for the public good solidified his reputation as the father of American landscape architecture.

Olmsted’s prolific career is a testament to his enduring vision and dedication to creating environments that enrich people’s and communities’ lives. Millions of people continue to enjoy his parks and public spaces today, offering a respite from urban life and a connection to the natural world.

Park Movement: Olmsted pioneered the park movement, which advocated for creating large public parks in urban areas. He believed parks were essential for city dwellers’ health, well-being, and social interaction.

Frederick Law Olmsted was a champion of the Park Movement. This social and political movement emerged in the mid-19th century, advocating for creating large, accessible public parks within urban areas. Olmsted firmly believed that parks were essential for city dwellers’ physical and mental health, providing a vital escape from the crowded, polluted, and stressful urban environment.

Fundamental Principles of the Park Movement:

-

-

Accessible Green Spaces: The Park Movement aimed to create large, open spaces filled with greenery, trees, and natural features that would be easily accessible to all members of society, regardless of social class.

-

Promoting Health and Well-being: Olmsted and other movement proponents believed that exposure to nature was essential for physical and mental health. Parks were seen as places where people could escape the stresses of city life, breathe fresh air, and engage in physical activity.

-

Fostering Social Interaction: Parks were also envisioned as spaces for social interaction and community building. They provided opportunities for people from different backgrounds to come together, relax, and enjoy shared experiences.

-

Democratic Values: The Park Movement embodied democratic ideals, emphasizing the importance of providing public spaces that were open and accessible to all citizens.

-

Olmsted’s Influence:

Olmsted’s work was instrumental in advancing the goals of the Park Movement. His designs for Central Park in New York City and other urban parks across the United States set a new standard for public park design. He created landscapes that were both beautiful and functional, offering a variety of experiences and activities for visitors.

Olmsted’s parks were not just green spaces but carefully designed environments incorporating various features to promote health, well-being, and social interaction. He used winding paths, varied topography, and diverse plantings to create a sense of discovery and adventure. He also included playgrounds, sports fields, and picnic areas to encourage physical activity and social gatherings.

Olmsted’s legacy as the father of American landscape architecture and a champion of the Park Movement is undeniable. Millions continue to enjoy his parks and public spaces today, providing a vital connection to nature and inspiration for future generations.

Naturalistic Design: Olmsted’s designs emphasized natural beauty and incorporated elements such as meadows, woodlands, lakes, and winding paths to create a sense of escape from the urban environment.

Frederick Law Olmsted’s design philosophy centered on the concept of naturalistic design. He aimed to create urban parks that would offer city dwellers a respite from the noise,

pollution, and stress of urban life, allowing them to connect with nature and experience its therapeutic benefits.

Olmsted’s designs were characterized by deliberately avoiding artificiality and a deep respect for the natural landscape. He sought to enhance the existing features of the land, such as rolling hills, valleys, and bodies of water, rather than imposing a rigid geometric structure upon them.

Some of the key elements of Olmsted’s naturalistic design include:

-

Meadows: Open, grassy areas that evoke a sense of tranquility and provide space for picnics, games, and relaxation.

-

Woodlands: Densely planted areas with various trees and shrubs, offering shade, privacy, and a sense of enclosure.

-

Lakes and Ponds: Water features that add beauty, tranquility, and recreational opportunities to the landscape.

-

Winding Paths: Meandering paths that encourage exploration and discovery, leading visitors through different landscapes and offering changing perspectives.

-

Scenic Vistas: Carefully framed views that highlight the landscape’s natural beauty and create a sense of awe and wonder.

Olmsted’s naturalistic designs not only provided aesthetic pleasure but also served a practical purpose. They offered city dwellers a place to escape the stresses of urban life, breathe fresh air, and engage in physical activity. His parks’ diverse landscapes and features catered to various interests and activities, ensuring that everyone could find something to enjoy.

Olmsted’s legacy of naturalistic design continues to inspire landscape architects and urban planners today. His parks and public spaces remain some of the most beloved and heavily used in the world, demonstrating the enduring power of nature to enhance our lives and well-being.

Social Consciousness: Olmsted’s designs were not just about aesthetics; they also reflected his social conscience and belief in providing public spaces for all members of society, regardless of social class.

Frederick Law Olmsted was not only a visionary landscape architect but also a social reformer deeply concerned with the well-being of his fellow citizens. His designs for public parks and spaces were informed by a strong social conscience and a belief in providing equitable access to nature for all members of society.

Olmsted’s social consciousness manifested in several ways in his work:

-

Inclusivity: He designed parks open to everyone, regardless of social class or economic status. He believed that all people deserved access to beautiful and refreshing natural spaces, and he deliberately created parks that catered to a wide range of interests and activities.

-

Democratic Values: Olmsted saw parks as essential components of a democratic society, providing spaces where people from all walks of life could interact. He believed that shared experiences in nature could foster social cohesion and understanding.

-

Social Reform: Olmsted’s concern for social justice extended beyond his park designs. He advocated for the abolition of slavery and supported other progressive causes, such as improving working conditions and providing educational opportunities for the poor.

Olmsted’s social conscience is evident in his design choices. He intentionally created spaces that encouraged interaction and fostered a sense of community. For example, he often included features like playgrounds, picnic areas, and bandstands, which provided opportunities for people to gather and enjoy shared experiences.

He also paid attention to the needs of different groups within society. In Central Park, he designed separate areas for carriages and pedestrians, recognizing that users had different needs and preferences. He also incorporated elements like the Dairy, where children could get fresh milk, and the Children’s District, a designated play area for young visitors.

Olmsted’s commitment to social equity and his belief in the power of nature to improve people’s lives made him a true pioneer in landscape architecture. Millions continue to enjoy his parks and public spaces today, serving as a testament to his enduring legacy as a social reformer and a champion of public access to nature.

Father of American Landscape Architecture: Olmsted is the father of American landscape architecture, having shaped the field with his innovative designs and influential writings.

Frederick Law Olmsted is rightfully considered the father of American landscape architecture. His visionary designs, innovative ideas, and prolific writings revolutionized the field and left an enduring legacy on the American landscape.

Olmsted’s contributions to landscape architecture are numerous and far-reaching:

-

- Pioneering Public Parks: Olmsted championed the creation of public parks as essential components of urban life. His designs for Central Park in New York City, Prospect Park in Brooklyn, and the Emerald Necklace in Boston set a new standard for park design, emphasizing natural beauty, recreational opportunities, and social interaction. These parks became models for urban green spaces across the United States and worldwide.

-

- Naturalistic Design: Olmsted’s designs emphasized integrating nature into urban environments. He used natural elements like meadows, woodlands, lakes, and winding paths to create landscapes that offered city dwellers a sense of escape and tranquility. His naturalistic style revolutionized American landscape design, moving away from the formal European gardens that were popular then.

-

-

Social Consciousness: Olmsted’s work was deeply rooted in his social conscience. He believed that parks should be accessible to all, regardless of social class, and that they should promote social interaction and community building. His designs reflected his commitment to creating spaces that would benefit all citizens’ physical and mental health.

-

Influence on Urban Planning: Olmsted’s ideas about the importance of parks and green spaces in urban planning have had a lasting impact on how cities are designed and developed. His work helped to establish landscape architecture as a distinct profession and inspired the creation of countless parks and public spaces across the United States.

-

- Prolific Writer: Olmsted was a prolific writer, publishing numerous articles, reports, and books on landscape architecture, urban planning, and social issues. His writings helped to disseminate his ideas and inspire a new generation of landscape architects.

Olmsted’s legacy extends beyond his projects. His vision, creativity, and social consciousness have left an indelible mark on landscape architecture and the American landscape. His parks and public spaces continue to provide millions of people solace, inspiration, and recreation. In contrast, his ideas continue to shape our thinking about the relationship between nature and the built environment.

Transformative Impact: His work transformed urban planning in the United States and inspired the creation of public parks in cities worldwide.

Frederick Law Olmsted’s impact on urban planning was transformative. He spearheaded a movement that fundamentally changed the way cities thought about and incorporated green spaces, and his influence continues to be felt today in urban planning and design around the world.

Transforming Urban Planning in the United States:

-

Park Systems: Olmsted was instrumental in establishing interconnected park systems within cities. His designs for the Emerald Necklace in Boston and the park system in Buffalo, New York, demonstrated the importance of linking green spaces to create a network of recreational and natural areas that all residents could enjoy.

-

Suburban Development: Olmsted’s influence extended beyond urban parks to the design of suburban communities. He envisioned suburbs as places where residents could enjoy the benefits of nature while still living close to urban centers. His designs for Riverside, Illinois, and other suburban communities incorporated parks, greenways, and tree-lined streets, creating a more livable and sustainable environment.

-

Institutional Landscapes: Olmsted also designed landscapes for various institutions, including hospitals, universities, and government buildings. His work on the U.S. Capitol grounds and the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina exemplified his ability to create beautiful and functional landscapes that complemented the architecture of these buildings.

Inspiring Public Parks Worldwide:

Olmsted’s ideas about the importance of public parks and green spaces resonated far beyond the United States. His work inspired the creation of similar parks in cities around the world, including:

-

Mount Royal Park in Montreal, Canada

-

Parc des Buttes-Chaumont in Paris, France

-

Park Güell in Barcelona, Spain

These parks, and countless others, owe a debt to Olmsted’s vision and his belief in the power of nature to enhance the quality of urban life.

Olmsted’s legacy includes innovation, social consciousness, and enduring impact. His work transformed urban planning and design, leaving a lasting imprint on cities across the globe. The parks and public spaces he created provide invaluable benefits to communities, offering a place for recreation, relaxation, and connection with the natural world.

Enduring Legacy: Millions of people enjoy Olmsted’s parks and public spaces today, providing a respite from urban life and a connection to nature.

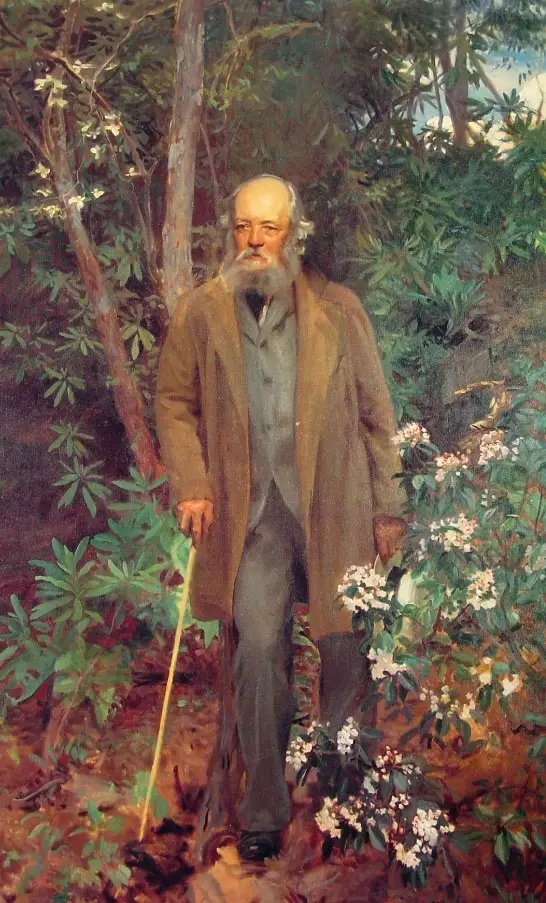

Frederick Law Olmsted, oil painting by John Singer Sargent, 1895, Biltmore Estate, Asheville, North Carolina (Wiki Image).

Enduring Legacy of Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted’s legacy is reflected in the millions of people who enjoy his parks and public spaces today. His designs provide a vital respite from urban life and a profound connection to nature. Olmsted’s pioneering work in landscape architecture laid the foundation for the modern concept of public parks as essential components of urban living, promoting both physical and mental well-being.

Notable Quotes by Frederick Law Olmsted

- On the Purpose of Parks: