Aristotle, Leonardo da Vinci, and Benjamin Franklin Compared: Polymathic Genius

That’s a fantastic trio to compare as iconic polymaths across different eras! Let’s examine their diverse interests, shared traits, and the unique contexts that shaped their polymathic genius.

Areas of Expertise

- Aristotle (384 – 322 BC):

- Philosophy: Metaphysics, ethics, logic, political theory – his influence is enormous

- Natural Sciences: Biology, zoology, physics, meteorology

- Rhetoric, Literature, and Poetics: He analyzed dramatic theory and persuasive communication

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519):

- Visual Arts: Painter (Mona Lisa!), sculptor, architect

- Engineering & Inventions: Flying machines, war machines, anatomical studies

- Scientific Observation: Detailed studies of nature, anatomy, optics

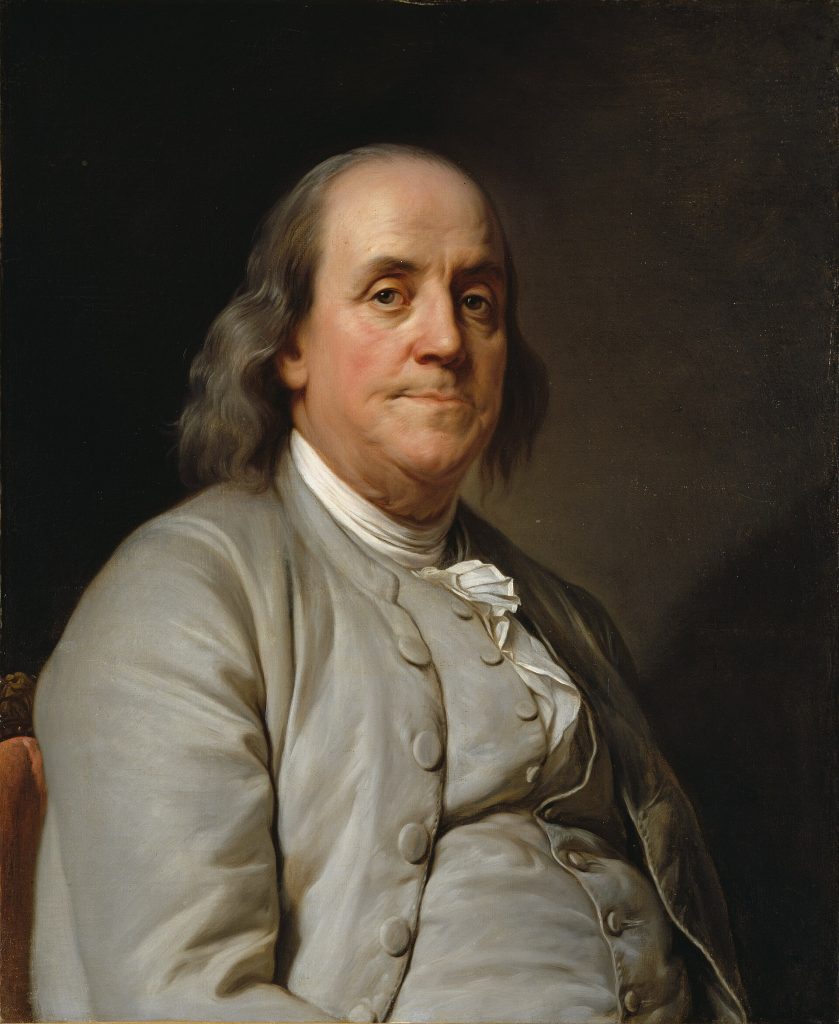

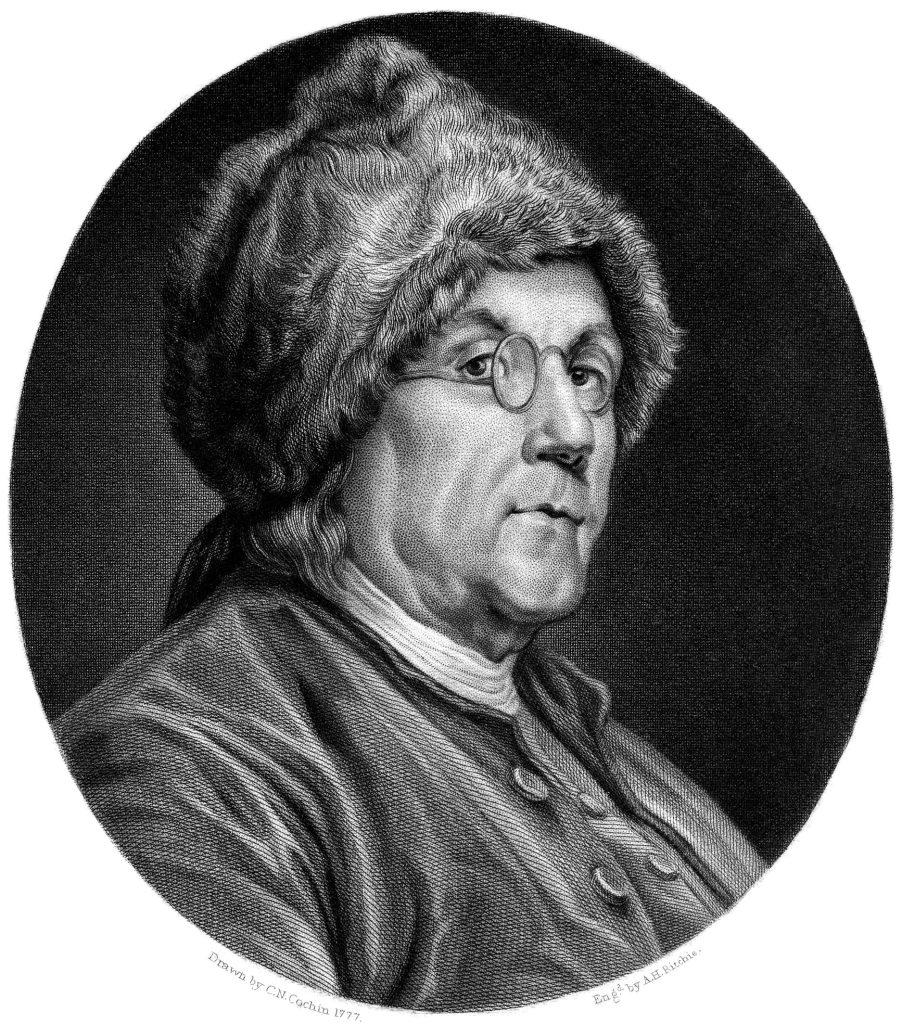

- Benjamin Franklin (1706 – 1790):

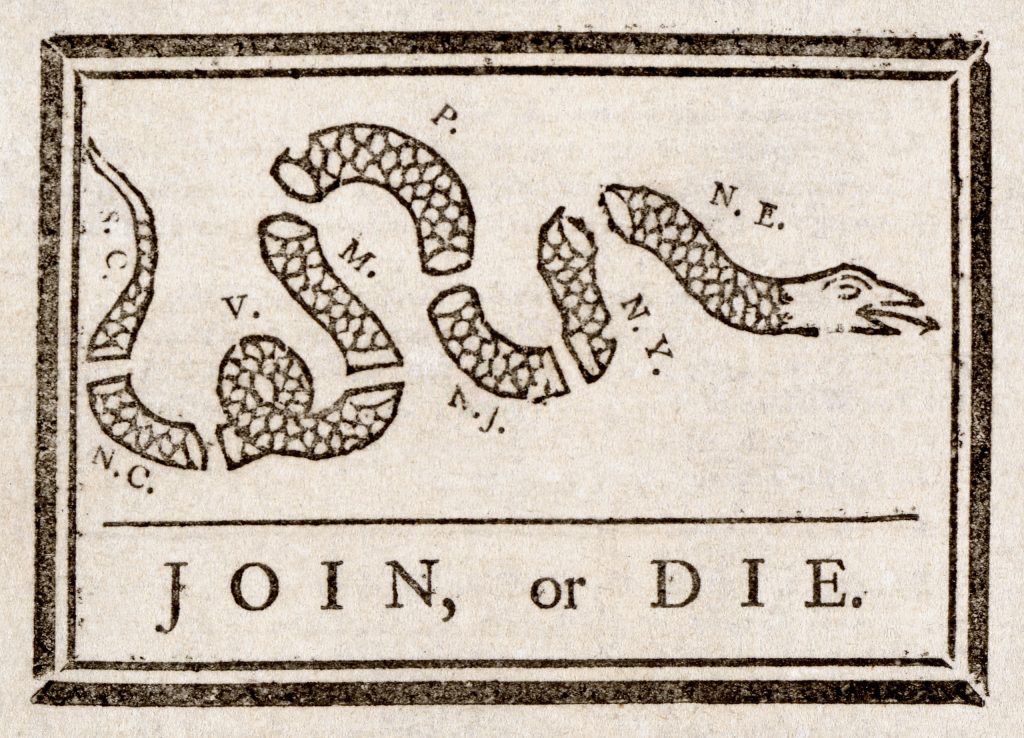

- Statesman & Diplomat: Key figure in American founding

- Science: Electricity experiments, inventions (lightning rod, bifocals)

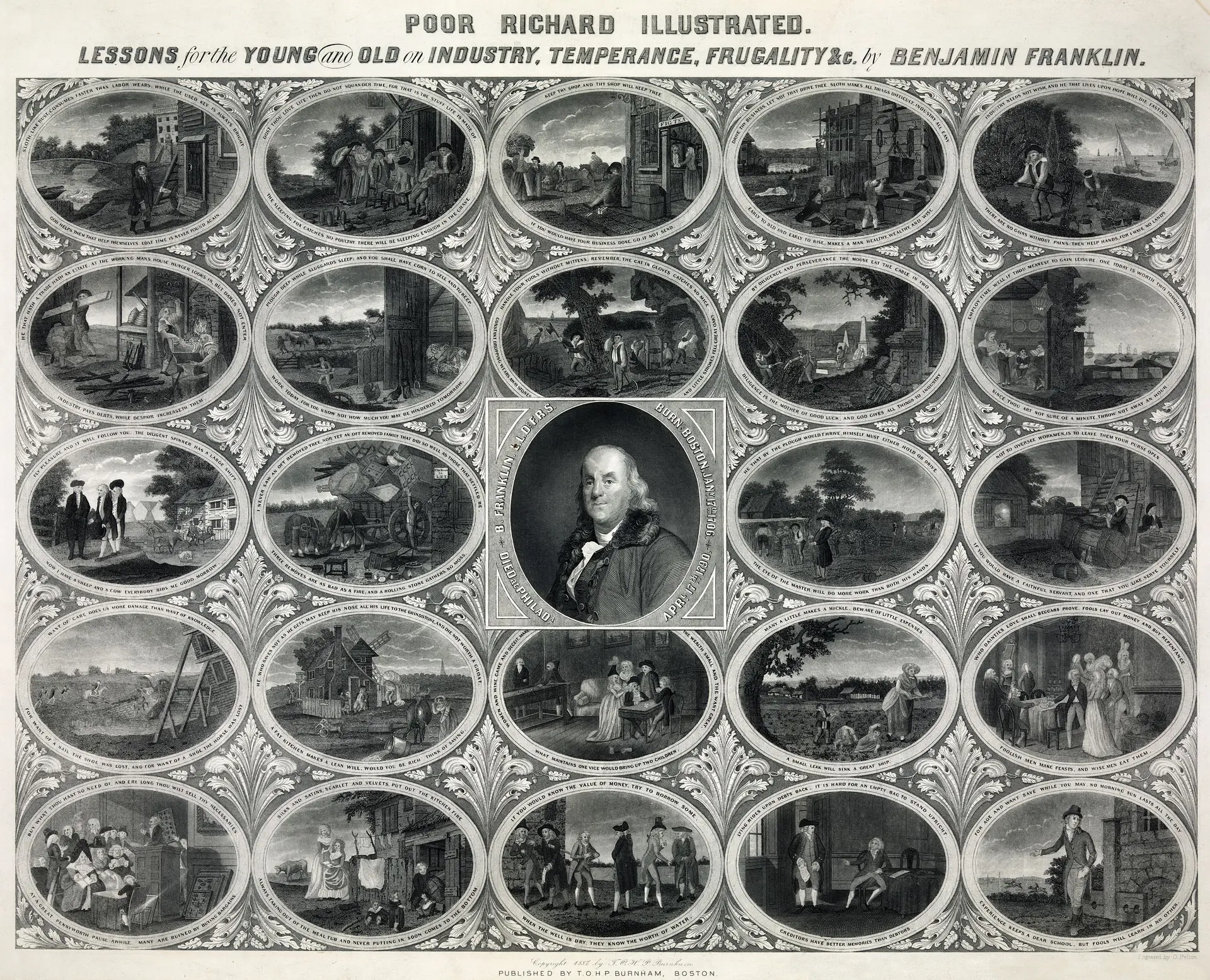

- Writer & Publisher: Almanacs, essays, his printing press

Common Threads

- Unquenchable Curiosity: Each possessed a voracious appetite for knowledge, refusing to be confined by the boundaries of their time.

- Observation as Foundation: They keenly observed the world, their understanding fueled by firsthand investigation and experimentation.

- Crossing Boundaries: They connected seemingly disparate fields. Aristotle linked logic with biology, da Vinci fused art with engineering, and Franklin combined science with practical invention.

- Pursuit of the Ideal: Each sought to understand underlying principles, aiming for mastery in diverse pursuits.

The Influence of Their Times

- Aristotle: Greek society valued intellectual inquiry. His access to patronage allowed dedicated study, though limited by the scientific tools of his time.

- Da Vinci: The Renaissance’s spirit of discovery and patronage of the arts fueled his work, but he also faced constraints of available technology.

- Franklin: The Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason and the practical application of science suited him well. He embodied a more utilitarian approach to knowledge.

Unique Strengths

- Aristotle: The systematizer. He laid the foundations of Western philosophical thought and scientific classification methodologies.

- Da Vinci: The visionary artist. His anatomical drawings, inventions, and artistic masterpieces demonstrated an extraordinary mind bridging art and science.

- Franklin: The pragmatic innovator. He connected scientific discovery with tangible inventions and civic improvements, demonstrating the power of applied knowledge.

Legacy

All three left indelible marks, even though their most famous works may sometimes overshadow their full polymathic breadth:

- Aristotle: Foundation of Western thought for centuries.

- Da Vinci: Embodiment of the Renaissance Man ideal.

- Franklin: Symbol of American ingenuity and Enlightenment ideals.

Where Would You Like to Go Deeper? We could:

- Analyze a specific invention or artwork where their polymath tendencies are obvious

- Discuss how their environment (Ancient Greece, Renaissance Italy, Enlightenment America) impacted their opportunities and constraints

- Debate which one comes closest to a “true” universal polymath

Let me know what interests you most!

Aristotle History

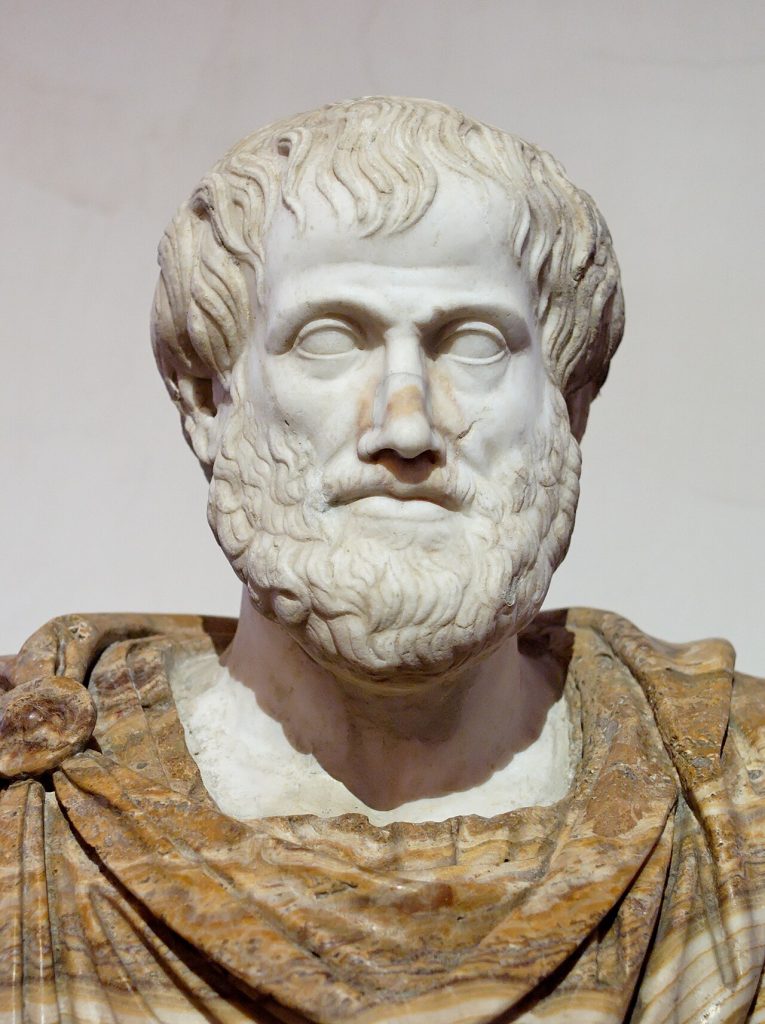

Roman copy (in marble) of a Greek bronze bust of Aristotle by Lysippos (c. 330 BC), with modern alabaster mantle (Wiki Image).

- “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” – This highlights Aristotle’s belief in systems. The full potential of something is only realized when elements work together, not in isolation.

- “Knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom.” – Emphasizes that self-awareness is the groundwork for personal growth, sound judgment, and a meaningful life.

- “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.” – Advocates for critical thinking and considering multiple perspectives, not blindly accepting ideas.

- “All men by nature desire to know.” – Humans have an innate thirst for knowledge and understanding of the world, according to Aristotle.

- “The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance.” – True art delves deeper than surface-level representation, aiming to reveal more profound truths and meanings.

- “Excellence is never an accident. It is always the result of high intention, sincere effort, and intelligent execution; it represents the wise choice of many alternatives – choice, not chance, determines your destiny.” – This emphasizes that achieving excellence requires deliberate choices, discipline, and thoughtful action.

- “Happiness depends upon ourselves.” – Aristotle believed true happiness (or eudaimonia) was achieved through cultivating virtue and living a fulfilling life in alignment with our purpose rather than from external circumstances.

- “Educating the mind without educating the heart is no education at all.” – True education must develop intellect and moral character for a well-rounded person.

- “Pleasure in the job puts perfection in the work.” – Personal satisfaction and fulfillment in a task lead to better results.

- “The energy of the mind is the essence of life.” – The act of thinking, learning, and exploring fuels our existence and gives it vitality.

| Year (approx.) | Age (approx.) | Events & Developments | Polymathic Pursuits |

|---|---|---|---|

| 384 BC | 0 | Born in Stagira, Chalcidice, Greece (northern Aegean coast). His father, Nicomachus, was a physician to the king of Macedon. | |

| 367 BC | 17 | Travels to Athens to join Plato’s Academy. Begins 20 years as a student and researcher at the Academy. | – Immersed in philosophy, mathematics, and the natural sciences. <br> – Likely begins his writing and investigations. |

| 347 BC | 37 | Leaves Athens after Plato’s death. Travels to Assos in Asia Minor (modern Turkey), then to Lesbos. | – Conducts research in marine biology. <br> – Tutors Hermias, the ruler of Atarneus. |

| 343 BC | 41 | King Philip II of Macedon summoned him to Pella to tutor his son, Alexander (the future Alexander the Great). | – Instructs Alexander in philosophy, literature, and politics. <br> – Likely influences Alexander’s worldview and ambitions. |

| 335 BC | 49 | He returns to Athens and finds his school, the Lyceum. He then taught and conducted research for the next 12 years. | – Writes extensively on various subjects, including logic, physics, metaphysics, ethics, politics, rhetoric, and poetics. <br> – Developed his philosophical system, distinct from Plato’s. |

| 323 BC | 61 | Leaves Athens after Alexander the Great’s death due to anti-Macedonian sentiment. Goes to Chalcis, Euboea. | |

| 322 BC | 62 | Dies in Chalcis. |

Absolutely! Here’s a dive into the history of Aristotle, one of the most influential philosophers of all time:

Early Life

- Born: 384 BCE in Stagira, a small town in Northern Greece.

- Family: His father, Nicomachus, was the personal physician to the King of Macedon.

- Orphaned: Sadly, both of Aristotle’s parents died when he was young, and a guardian raised him.

Education and Plato

- Plato’s Academy: At age 17, Aristotle moved to Athens and joined Plato’s famed Academy.

- Brilliant Student: He was a star pupil and stayed at the Academy for 20 years, eventually becoming a teacher.

- Different Perspectives: While respecting Plato, Aristotle developed his distinct philosophical viewpoints on many subjects.

Tutor to Alexander the Great

- Royal Connection: Around 343 BCE, King Phillip II of Macedon summoned Aristotle to become the tutor of his son, Alexander.

- Shaping a Future Leader: He spent several years educating the young prince who would become Alexander the Great, one of history’s greatest conquerors.

The Lyceum and His Writings

- Founding His School: Returning to Athens around 335 BCE, Aristotle founded his school, the Lyceum.

- Prolific Writer: At the Lyceum, he composed many works covering logic, science, politics, ethics, metaphysics, and more. Unfortunately, many were written as lecture notes and not polished treatises, and some were lost entirely.

- Systematizing Knowledge: Aristotle’s great contribution was organizing existing knowledge into specific disciplines and laying the foundation for scientific inquiry for centuries.

Key Contributions:

Aristotle was a prolific writer and thinker; his works spanned many fields. Some of his most significant contributions include:

- Logic: Aristotle is considered the father of formal logic. He developed syllogistic reasoning, which had a profound influence on Western thought.

- Natural Sciences: He studied and wrote on various subjects, including physics, biology, zoology, meteorology, and astronomy. While some of his theories have been superseded by modern science, he laid important groundwork for scientific observation and classification.

- Metaphysics: Aristotle explored questions about being, existence, and the nature of reality. These investigations remain relevant in philosophy today.

- Ethics: His “Nicomachean Ethics” is one of the foundational works of virtue ethics. It examines the nature of happiness (eudaimonia) and how to achieve a fulfilling life through the development of moral character.

- Politics: In his “Politics,” Aristotle analyzed forms of government, explored the concept of the ideal state, and examined the roles of citizens and leaders.

- Rhetoric and Poetics: These works explore persuasive communication, effective language use (Rhetoric), and the principles of tragedy and dramatic storytelling (Poetry).

Later Life and Legacy

- Athens Departure: After Alexander the Great’s death, anti-Macedonian sentiment flared in Athens. Aristotle left the city in 323 BCE to avoid persecution.

- Death: He died in 322 BCE at the age of 62.

- Enduring Influence: Aristotle’s works were preserved despite his death and became the cornerstone of philosophy during the Middle Ages. His ideas continue to be studied and debated even today.

Let me know if you’d like a deeper look into his specific philosophies, his relationship with Plato, or his impact on later thinkers!

Aristotle YouTube Video

- Aristotle & Virtue Theory: Crash Course Philosophy #38 by CrashCourse:

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PrvtOWEXDIQ

- Views: 3,993,715

- Plato and Aristotle: Crash Course History of Science #3 by CrashCourse:

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rh0fxJkvL44

- Views: 1,840,485

- Aristotle: History’s Most Influential Thinker by Biographics:

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qD5O3vXj9eU

- Views: 969,737

- The Life and Philosophy of Aristotle by Let’s Talk Philosophy:

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pbl2OKOqRDc

- Views: 200,370

- Aristotle: Creating Foundations | Historical Documentary | Lucasfilm by Lucasfilm:

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_VKlS-UJXGQ

- Views: 37,545

Aristotle’s Early Life

-

Born: 384 BCE in Stagira, a small town in Northern Greece.

-

Family: His father, Nicomachus, was the personal physician to the King of Macedon.

-

Orphaned: Sadly, both of Aristotle’s parents died when he was young, and a guardian raised him.

School of Aristotle in Mieza, Macedonia, Greece (Wiki Image).

Here’s a more comprehensive look at Aristotle’s early life, expanding upon your points and adding some context:

Birth and Family:

- Born: 384 BCE in Stagira, Chalcidice, a region in Northern Greece.

- Father: Nicomachus, a respected physician who served King Amyntas III of Macedon. This connection likely influenced Aristotle’s later interest in biology and natural sciences.

- Mother: Phaestis, about whom little is known.

- Sibling: He had an older brother (Arimnestus) and a sister (Arimneste).

Tragic Losses & Guardianship:

- Orphaned: Both his parents passed away while Aristotle was still young. The exact ages or causes of their deaths are uncertain.

- Guardian: Proxenus of Atarneus became Aristotle’s guardian. Proxenus was not closely related, but he cared for Aristotle and provided for his education.

Upbringing and Education:

- Privileged Background: Despite his losses, Aristotle’s family background secured him a comfortable upbringing with access to educational opportunities.

- Early Influences: Exposure to medicine through his father and perhaps some degree of court life in Macedon would have shaped his early worldview.

- Possible Tutoring: It’s speculated that Proxenus, likely well-educated himself, may have played a role in Aristotle’s early studies.

The Move to Athens:

- A Turning Point: At around 17 years old, Aristotle journeyed to Athens, the intellectual heart of the Greek world. This marked a crucial transition.

- Plato’s Academy: He enrolled in Plato’s Academy, one of the foremost learning centers in the ancient world. This would become his academic home for the next two decades.

Let me know if you’d like to explore any aspect of his early life in more detail, such as the possible impact of his father’s profession or his relationship with Plato!

Education and Plato

-

Plato’s Academy: At age 17, Aristotle moved to Athens and joined Plato’s famed Academy.

-

Brilliant Student: He was a star pupil and stayed at the Academy for 20 years, eventually becoming a teacher.

-

Different Perspectives: While respecting Plato, Aristotle developed his distinct philosophical viewpoints on many subjects.

The School of Athens by Raphael (1509–1510), fresco at the Apostolic Palace, Vatican City. The fresco depicts a congregation of ancient philosophers, mathematicians, and scientists, with Plato and Aristotle featured in the center (Wiki Image).

You’ve accurately summarized the key points of Aristotle’s education and his complex relationship with Plato. Here’s a deeper dive into those aspects:

Plato’s Academy:

- Intellectual Mecca: The Academy wasn’t a school in the modern sense. It was a community of scholars engaged in philosophical discussion, research, and debate across various fields.

- Formative Influence: Plato’s teachings heavily influenced Aristotle. They discussed metaphysics, ethics, logic, natural sciences, and more.

- Not a Blind Follower: Aristotle immensely respected Plato, calling him “the man whom bad men have not even the right to praise.” However, he wasn’t a disciple and began developing his own distinct ideas.

Aristotle the Student-Turned-Teacher:

- Extended Tenure: His 20 years at the Academy weren’t just about absorbing knowledge. He contributed as a researcher and eventually taught his courses.

- Collaboration and Tension: Some sources suggest that Plato and Aristotle worked together at times, but there were also intellectual rivalries and disagreements.

Key Areas of Divergence:

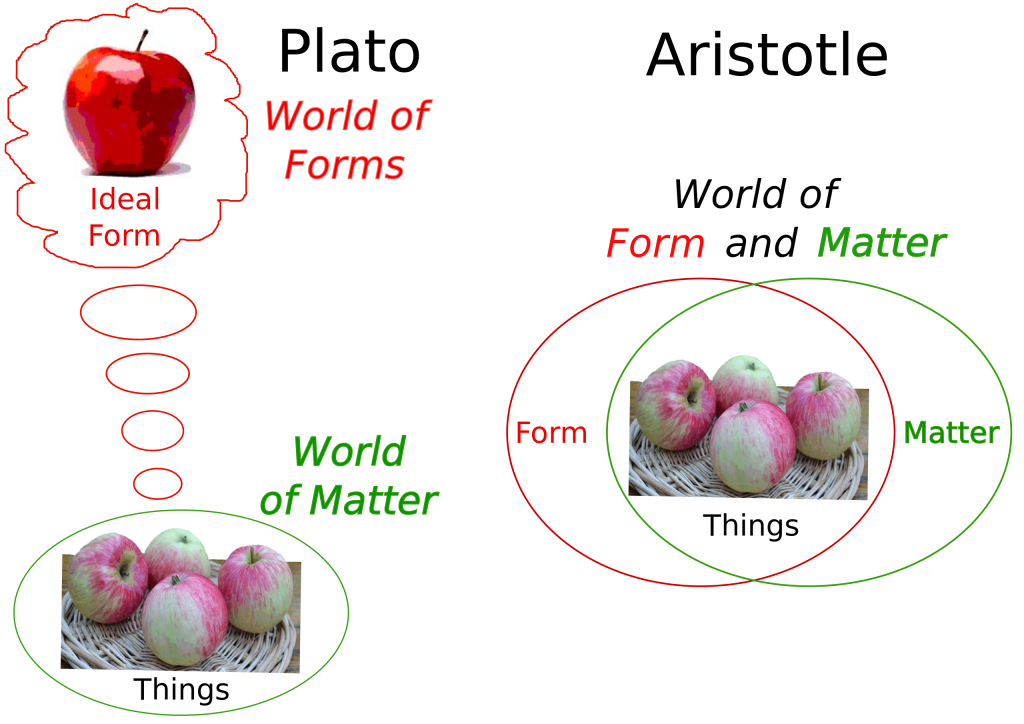

- Theory of Forms: Plato believed in perfect, abstract Forms (like Justice and Beauty) that exist independently of the physical world. Aristotle favored a focus on studying the forms inherent within things we experience through our senses.

- Logic and Method: Aristotle developed formal logic as we know it, emphasizing observation and categorization, while Plato often relied on more intuitive, dialectical arguments.

- Politics: Plato favored an idealized “Republic” ruled by philosopher-kings, while Aristotle was more pragmatic, analyzing and comparing different existing governing systems.

Legacy of the Relationship:

- Intellectual Giants: Plato and Aristotle remain two of the most profound thinkers in Western philosophy.

- Complementary, Not Opposite: Though their ideas differ, they grapple with similar fundamental questions. Studying both offers a richer understanding of philosophical inquiry.

Let me know if you’d like a closer look at a specific philosophical disagreement between them or want to explore the unique atmosphere of Plato’s Academy!

Tutor to Alexander the Great

-

Royal Connection: Around 343 BCE, King Phillip II of Macedon summoned Aristotle to become the tutor of his son, Alexander.

-

Shaping a Future Leader: He spent several years educating the young prince who would become Alexander the Great, one of history’s greatest conquerors.

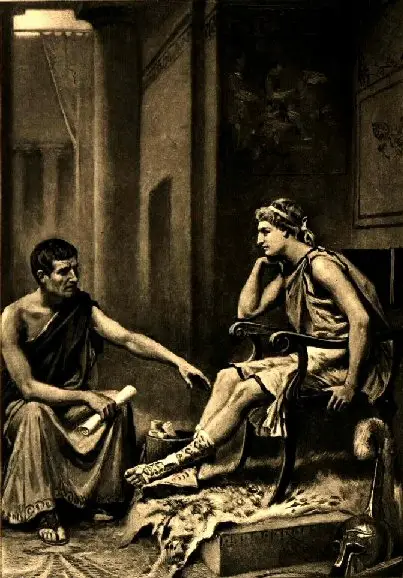

“Aristotle tutoring Alexander” by Jean Leon Gérôme Ferris (Wiki Image).

Absolutely! Here’s a deeper look at Aristotle’s role as tutor to Alexander the Great and the complexities of this relationship:

The Summoning:

- Phillip II’s Ambition: King Phillip II was a shrewd leader and military innovator who aimed to unify Greece and expand his kingdom. Recognizing his son’s potential, he sought the best education available.

- Choosing Aristotle: Aristotle’s reputation as a brilliant philosopher and polymath made him an ideal choice. His connections to the Macedonian court from his father’s time also likely played a role.

Tutorship at Mieza:

- Location: Aristotle established a school at Mieza, a sanctuary of the nymphs near the Macedonian capital, Pella. This idyllic setting provided a serene environment for learning.

- Curriculum: Aristotle instructed Alexander and likely other noble Macedonian youths in literature, politics, philosophy, science, and perhaps even medicine.

- Emphasis on Homer: Alexander deeply admired Homer’s Iliad and carried a copy on his conquests. Aristotle likely influenced this passion for the Greek classics.

Shaping a Worldview:

- Beyond Academics: Their lessons wouldn’t have been dry lectures. Aristotle aimed to instill critical thinking, an appreciation for Greek culture, and perhaps a sense of moral leadership and ambition.

- Intellectual Clash?: It’s easy to imagine the spirited, strong-willed Alexander challenging Aristotle’s teachings, leading to dynamic debate.

- Lasting Impact: It’s impossible to quantify the precise impact of Aristotle’s tutorship. Alexander’s later actions were a complex blend of ambition, military genius, and some degree of philosophical awareness potentially shaped by his teacher.

Divergence of Paths:

- Alexander’s Ascension: When Phillip II was assassinated in 336 BCE, Alexander became king, ending their formal teacher-student relationship.

- Conquests & Philosophy: Alexander’s focus shifted to military conquest and empire-building. Aristotle’s influence likely waned, though some argue echoes of his ethics can be seen in Alexander’s actions.

Legacy:

- Historical Fascination: Pairing the greatest conqueror with one of history’s greatest thinkers remains endlessly captivating.

- Open to Interpretation: Sources are slim, leading to speculation and differing perspectives on Aristotle’s true impact on Alexander’s life and rule.

Is there a particular aspect of their relationship or the educational setting at Mieza you’d like to explore further?

The Lyceum and His Writings

-

Founding His School: Returning to Athens around 335 BCE, Aristotle founded the Lyceum.

-

Prolific Writer: At the Lyceum, he composed many works covering logic, science, politics, ethics, metaphysics, and more. Unfortunately, many were written as lecture notes and not polished treatises, and some were lost entirely.

-

Systematizing Knowledge: Aristotle’s great contribution was organizing existing knowledge into specific disciplines and laying the foundation for scientific inquiry for centuries.

The site of the excavations of the Lyceum (Wiki Image).

Absolutely! Here’s a closer examination of Aristotle’s founding of the Lyceum and his vast legacy as a writer:

The Lyceum:

- A Rival Academy: The Lyceum was Aristotle’s new center of philosophical learning. Some speculate that the choice of location near the temple of Apollo Lyceus might have been a subtle jab at his old school, dedicated to Athena.

- Focus: It likely followed a similar model to Plato’s Academy, focusing on research, teaching in various subjects, and philosophical debate.

- The Peripatetics: Aristotle’s followers were sometimes known as the Peripatetics, thought to be due to his habit of walking and lecturing outdoors at the Lyceum.

- Legacy: The Lyceum continued long after Aristotle’s death, contributing to scholarship for centuries, though its influence gradually diminished.

Aristotle’s Writings:

- Prodigious Output: Even the surviving portion of his written work is considerable. It’s believed most were products of his time at the Lyceum.

- Esoteric vs. Exoteric: There’s a tradition differentiating between works intended for the public (“exoteric”) and internal lectures or research notes (“esoteric”). The surviving work likely falls into the latter category.

- Diverse Topics: Aristotle tackled logic, physics, zoology, metaphysics, ethics, political theory, rhetoric, poetry… there was very little he didn’t explore!

- Influence Despite Form: While his prose was not always the most elegant, the organization, rigor, and depth of his analysis had a transformative impact on how Western thinkers approached various fields.

Systematization of Knowledge:

- Defining Disciplines: More than specific discoveries, Aristotle’s power lay in his categorization of knowledge. He distinguished between theoretical, practical, and productive sciences.

- Methodological Foundation: His emphasis on observation, classification, and deduction from first principles laid the groundwork for scientific inquiry.

- Enduring Relevance: Even when his scientific conclusions were later revised, his methodological approaches and systems of categorization influenced thinkers long after him.

Would you like a deeper dive into…

- Specific works and their themes?

- The structure of the Lyceum?

- Aristotle’s approach to different fields of study?

Let me know!

Aristotle was a prolific writer and thinker; his works spanned many fields.

Logic: Aristotle is considered the father of formal logic. He developed syllogistic reasoning, which had a profound influence on Western thought.

Plato‘s forms exist as universals, like the ideal form of an apple. For Aristotle, matter and form belong to the individual thing (hylomorphism) (Wiki Image).

Plato‘s forms exist as universals, like the ideal form of an apple. For Aristotle, matter and form belong to the individual thing (hylomorphism) (Wiki Image).

You’re right! Here’s a breakdown of why Aristotle’s contributions to logic are so groundbreaking:

Before Aristotle:

- Reasoning existed, of course, but was more intuitive and informal.

- Arguments were often based on rhetoric and persuasion, not strictly valid steps.

Aristotle’s Revolution:

- Syllogisms: The core of his work was the syllogism. A typical example:

- Major Premise: All men are mortal.

- Minor Premise: Socrates is a man.

- Conclusion: Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

- Formalization: Aristotle dissected the structure of arguments like this, focusing on their form rather than their specific content.

- Categorical Logic: He analyzed how universal or particular statements (“All…”, “Some…”) interact to create valid or invalid deductions.

- Prior Analytics: His treatise on this subject laid the foundation for formal logic.

Why This Matters:

- Valid vs. Persuasive: Aristotle helped distinguish between logically sound arguments and those that merely sound convincing.

- Universal System: This wasn’t about specific topics. He provided rules of inference applicable to any field of knowledge.

- Science & Philosophy: His logic provided a tool for systematically building reliable knowledge and conducting reasoned debates.

Limitations and Development:

- Not the End of the Story: Later, logicians expanded upon, refined, and sometimes challenged Aristotle’s work. Modern logic is far more complex.

- Still Fundamental: Even with advances, Aristotle’s core system provided a starting point, with concepts like premises and conclusions still relevant today.

Let me know if you’d like to explore:

- Specific examples of syllogisms and common logical fallacies.

- Aristotle’s other logical works are beyond syllogism.

- How his logical framework influenced other fields of his thought!

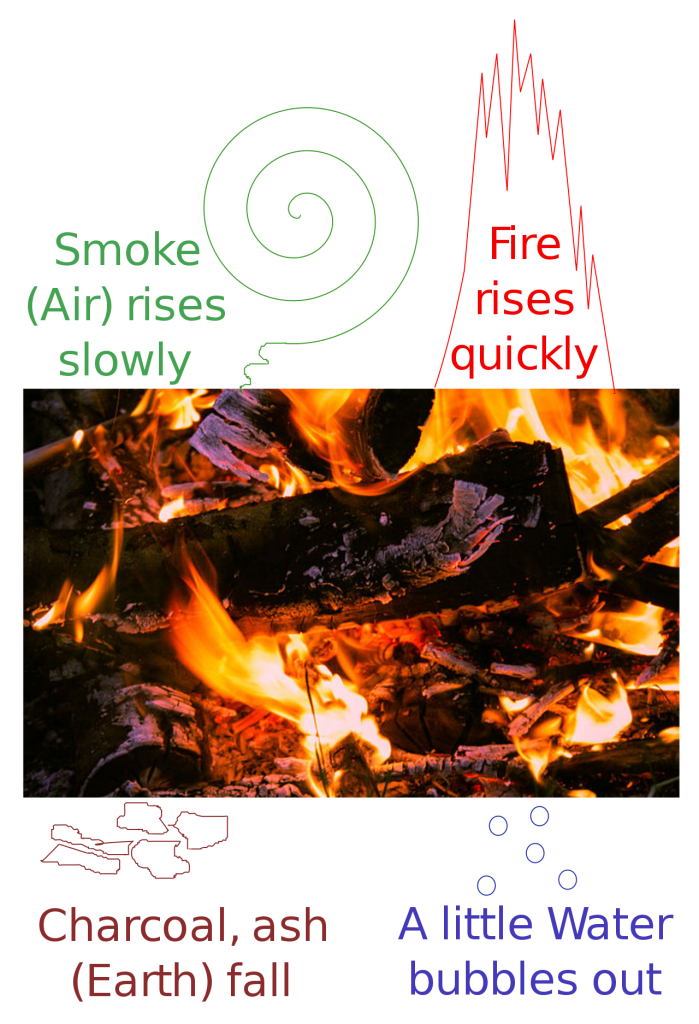

Natural Sciences: Aristotle studied and wrote on various subjects, including physics, biology, zoology, meteorology, and astronomy. While some of his theories have been superseded by modern science, he laid important groundwork for scientific observation and classification.

Empedocles and Aristotle’s four classical elements (fire, air, water, and earth) are illustrated with a burning log. The log releases all four elements as it is destroyed (Wiki Image).

| Group | Examples

(given by Aristotle) |

Blood | Legs | Souls

(Rational, Sensitive, Vegetative) |

Qualities

(Hot–Cold, Wet–Dry) |

| Man | Man | with blood | 2 legs | R, S, V | Hot, Wet |

| Live-bearing tetrapods | Cat, hare | with blood | 4 legs | S, V | Hot, Wet |

| Cetaceans | Dolphin, whale | with blood | none | S, V | Hot, Wet |

| Birds | Bee-eater, nightjar | with blood | 2 legs | S, V | Hot, Wet, except Dry eggs |

| Egg-laying tetrapods | Chameleon, crocodile | with blood | 4 legs | S, V | Cold, Wet except scales, eggs |

| Snakes | Water snake, Ottoman viper | with blood | none | S, V | Cold, Wet except scales, eggs |

| Egg-laying fishes | Sea bass, parrotfish | with blood | none | S, V | Cold, Wet, including eggs |

| (Among the egg-laying fishes):

placental selachians |

Shark, skate | with blood | none | S, V | Cold, Wet, but placenta-like tetrapods |

| Crustaceans | Shrimp, crab | without | many legs | S, V | Cold, Wet except shell |

| Cephalopods | Squid, octopus | without | tentacles | S, V | Cold, Wet |

| Hard-shelled animals | Cockle, trumpet snail | without | none | S, V | Cold, Dry (mineral shell) |

| Larva-bearing insects | Ant, cicada | without | 6 legs | S, V | Cold, Dry |

| Spontaneously generating | Sponges, worms | without | none | S, V | Cold, Wet or Dry, from earth |

| Plants | Fig | without | none | V | Cold, Dry |

| Minerals | Iron | without | none | none | Cold, Dry |

Aristotle’s Scala naturae (highest to lowest) (Wiki Table).

You’re spot on! Here’s a deeper dive into Aristotle’s contributions to the natural sciences and their historical significance:

Aristotle, the Natural Philosopher:

- Keen Observer: Aristotle was fascinated by the natural world and emphasized firsthand observation to understand how things function.

- Classification Pioneer: He tirelessly collected specimens, grouped organisms by shared traits, and sought underlying principles of order.

- Broad Scope: His focus included:

- Physics: Motion, change, the elements, and celestial bodies.

- Biology & Zoology: Animal anatomy, reproduction, classification, and behavior.

- Meteorology: Weather patterns, atmospheric phenomena, and the Earth’s composition.

Key Contributions:

- Methodical Approach: Aristotle’s observations and classifications laid a foundation for scientific inquiry, even if his specific conclusions weren’t always accurate.

- Biological Insights: His dissections were remarkably detailed for the time, and he correctly identified dolphins and whales as mammals, for example.

- Four Causes: He theorized that understanding why something exists requires looking at four causes: material, formal, efficient, and final (purpose).

- Teleology: The idea of purpose in nature, that things are designed with an end goal, was highly influential in his work.

Limitations & Historical Context:

- Lack of Technology: Without microscopes, telescopes, or modern experimental tools, it’s remarkable how much Aristotle could deduce.

- Geocentric Universe: Like most thinkers, he believed in an Earth-centered cosmological model.

- Errors & Corrections: Modern science has revised many of his specific ideas (e.g., spontaneous generation, elements being earth, air, fire, water).

His Legacy:

- Not Right, but Important: More than being ‘right,’ Aristotle demonstrated the power of a systematic, questioning approach to the natural world.

- Language & Influence: His terms and classification systems shaped scientific thought even when his specifics were later overturned.

- Inspiration: His work sparked centuries of scientists to refine methods, test his hypotheses, and further unravel the mysteries of nature.

Would you like to know more about…

- Specific works like “History of Animals” or “Meteorology”?

- What were the misconceptions he held, and how were they later corrected?

- What are the broader philosophical ideas underpinning his scientific approach?

Metaphysics: Aristotle explored questions about being, existence, and the nature of reality. These investigations remain relevant in philosophy today.

- “All men by nature desire to know.” – This reflects Aristotle’s belief in the inherent human curiosity and drive to understand the world around us.

- “The ultimate value of life depends upon awareness and the power of contemplation rather than upon mere survival.” – Aristotle emphasizes the importance of intellectual and spiritual growth as essential components of a fulfilling life.

- “The investigation of the truth is in one way hard, in another easy.” – This quote acknowledges the challenges and rewards of pursuing knowledge and understanding.

- “The energy of the mind is the essence of life.” – This suggests that our capacity for thought, reasoning, and intellectual engagement makes us truly human.

- “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.” – This highlights the importance of critical thinking and being open to different perspectives without necessarily adopting them.

- “To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true.” – This statement is the basis of Aristotle’s Law of Non-Contradiction, a fundamental principle in logic.

- “Things that are eternal are all at once.” – This refers to his concept of eternity as a complete, simultaneous whole, in contrast to time, which unfolds sequentially.

- “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” – This quote is often attributed to Aristotle, though not directly found in his works. It conveys the idea that the combined properties of a whole can exceed the sum of its individual components.

- “If there is no first, there will be no last.” – This reflects Aristotle’s belief in a Prime Mover (or God) as the uncaused cause that initiates the chain of motion and change in the universe.

- “Nature does nothing uselessly.” – This emphasizes Aristotle’s teleological view of nature, that everything has a purpose or function that contributes to its existence and overall order.

Absolutely! Aristotle’s Metaphysics is a cornerstone of philosophical inquiry, and here’s why:

What is Metaphysics?

- The term itself means “after the physics.” It’s less about a specific subject and more about the fundamental questions underlying everything else.

- Key inquiries include:

- What is existence? What does it mean for something to “be”?

- Substance vs. Accidents: What are the essential properties of a thing vs. the changes it undergoes?

- Causation: What causes exist, and how do they explain change and phenomena?

- God & First Mover: Aristotle argued for a Prime Mover, the uncaused cause behind all change.

Key Concepts in Aristotle’s Metaphysics:

- Potential vs. Actual: A key distinction – an acorn has the potential to be an oak tree, and a block of marble has the potential to be a statue.

- Categories of Being: Aristotle categorized what exists, helping structure his analysis of existence and reality.

- Form and Matter: For Aristotle, form gives a thing its essence (its “whatness”), while the matter is its underlying stuff.

- Four Causes: As mentioned earlier, his analysis of why anything exists involves four aspects: material, formal, efficient (the agent that brings it about), and final (the purpose).

Why It Still Matters:

- Unanswered Questions: While science addresses the ‘how,’ philosophy wrestles with the deeper ‘why,’ which still fascinates us today.

- Framework of Thought: Aristotle’s categories, terms, and concepts provide a way to analyze ideas like existence, change, and causation systematically.

- Debates Continue: Philosophers build on, challenge, and refine their foundational ideas even centuries later.

Impact:

- Western Thought Foundation: It’s nearly impossible to understand medieval philosophy or major developments in modern thought without grappling with Aristotle’s Metaphysics.

- Other Fields: His ideas about causation and purpose influenced theology, and his thoughts on substances and properties are echoed in modern scientific debates.

Let me know if you’d like to dive into:

- Specific arguments from the Metaphysics (they can be dense!)

- Compare Aristotle’s stance to that of other philosophers on these same big questions.

- Explore the influence of his Metaphysics on a later thinker!

Ethics: Aristotle’s “Nicomachean Ethics” is one of the foundational works of virtue ethics. It examines the nature of happiness (eudaimonia) and how to achieve a fulfilling life through the development of moral character.

| Too little | Virtuous mean | Too much |

| Humbleness | High-mindedness | Vainglory |

| Lack of purpose | Right ambition | Over-ambition |

| Spiritlessness | Good temper | Irascibility |

| Rudeness | Civility | Obsequiousness |

| Cowardice | Courage | Rashness |

| Insensibility | Self-control | Intemperance |

| Sarcasm | Sincerity | Boastfulness |

| Boorishness | Wit | Buffoonery |

| Shamelessness | Modesty | Shyness |

| Callousness | Just resentment | Spitefulness |

| Pettiness | Generosity | Vulgarity |

| Meanness | Liberality | Wastefulness |

Virtues and their accompanying vices (Wiki Table).

- “Happiness is the meaning and the purpose of life, the whole aim and end of human existence.” – This sets the stage for the entire work, defining happiness (eudaimonia) as the ultimate goal of human life.

- “One swallow does not make a summer, neither does one fine day; similarly, one day or brief time of happiness does not make a person entirely happy.” – This emphasizes that true happiness is not fleeting pleasure but a sustained state achieved through virtuous living.

- “Every virtue is a mean between two vices, one of excess and the other of deficiency.” – This introduces the concept of the Golden Mean, where virtue lies in finding the right balance between extremes.

- “It is easy to perform a good action, but not easy to acquire a settled habit of performing such actions.” – This highlights the importance of cultivating virtues through practice and habit.

- “The ultimate value of life depends upon awareness and the power of contemplation rather than upon mere survival.” – This suggests that intellectual and spiritual development are essential for a truly fulfilling life.

- “Anybody can become angry – that is easy, but to be angry with the right person and to the right degree and at the right time and for the right purpose, and in the right way – that is not within everybody’s power and is not easy.” – This emphasizes the importance of regulating emotions and expressing them appropriately.

- “With regard to excellence, it is not enough to know, but we must try to have and use it.” – This underscores the importance of not just understanding virtue but actively practicing it in our daily lives.

- “The educated differ from the uneducated as much as the living differs from the dead.” – This stresses the transformative power of education and learning in shaping our lives.

- “Friendship is essentially a partnership.” – Aristotle viewed friendship as a mutual relationship based on goodwill, shared values, and mutual support.

- “Moral excellence comes about as a result of habit. We become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts.” – This reinforces the idea that virtue is developed through repeated practice and action.

Absolutely! Here’s a breakdown of why Aristotle’s “Nicomachean Ethics” remains influential and how it reshaped thinking about morality:

Eudaimonia:

- Not Mere Happiness: The central concept is often translated as “happiness,” but Aristotle means something deeper: humans flourishing and living a life of fulfillment.

- Function Argument: He argues that humans have a function or purpose, like everything else—our good lies in fulfilling that function to the best of our ability.

- Reason & Excellence: Our distinctive human function is tied to reason. Therefore, a fulfilled life involves cultivating intellectual and moral excellence.

The Golden Mean:

- Virtue as Balance: Aristotle believed virtues (like courage, temperance, and generosity) are found in a middle ground between extremes—cowardice vs. Recklessness, for example.

- Practical, not Rigid: The mean isn’t a strict mathematical midpoint. It’s context-dependent, requiring judgment and finding the right balance for a particular situation.

- Habituation: We become virtuous by pondering ideals and practicing good habits until they become second nature.

Focus on Character:

- Beyond Rules: Aristotle’s ethics isn’t about memorizing a rule book. It’s about becoming the person who naturally makes the right choices.

- Internal Motivation: True goodness springs from a character desiring the right things, not just blind obedience.

- Importance of Community: We develop virtues within a social context, learning from good examples and a society that values excellence.

Legacy of the Nicomachean Ethics:

- Virtue Ethics: His focus on character as the root of moral action became a major school of ethical thought, offering an alternative to rule-based systems.

- Practical Guidance: Unlike some abstract philosophies, Aristotle offers advice on everyday choices and how striving for virtue can lead to a truly good life.

- Still Debated: Philosophers continue to grapple with the specifics of his approach – is there a universal human function? Are virtues culturally relative?

Let me know if you want to explore:

- Specific virtues in detail (and their corresponding vices)

- How Aristotle’s concept of eudaimonia relates to modern ideas of well-being

- Comparisons between virtue ethics and other ethical systems (duty-based or consequence-based)

Politics: In his “Politics,” Aristotle analyzed forms of government, explored the concept of the ideal state, and examined the roles of citizens and leaders.

- “Man is by nature a political animal.” – This famous quote highlights Aristotle’s belief that humans are inherently social creatures who thrive in communities and political structures.

- “It is evident that the state is a creation of nature and that man is by nature a political animal.” – This reinforces the idea that political life is natural and essential for human flourishing.

- “The good of the many outweighs the good of the few or the individual.” – This reflects Aristotle’s emphasis on the common good as the ultimate goal of politics.

- “The basis of a democratic state is liberty.” – Aristotle identifies liberty as a core principle of democracy but warns of its potential to devolve into mob rule.

- “He who is unable to live in society, or who has no need because he is sufficient for himself, must be either a beast or a god.” – This quote underscores the importance of social interaction and cooperation for human beings.

- “The worst form of inequality is to try to make unequal things equal.” – Aristotle recognized that not all individuals are equal in abilities and contributions, and trying to force equality can lead to injustice.

- “Law is order, and good law is good order.” – This emphasizes the importance of just and well-structured laws in maintaining a stable and flourishing society.

- “The rule of law is better than the rule of any individual.” – This advocates for the importance of laws and institutions over the arbitrary rule of a single person.

- “It is not always the same thing to be a good man and a good citizen.” – Aristotle acknowledges the tension between individual morality and civic duty demands.

- “The many are more incorruptible than the few; they are like the greater quantity of water which is less easily corrupted than a little.” – This suggests that a larger group of people is less susceptible to corruption than a smaller, elite group.

Absolutely! Here’s a look at Aristotle’s political ideas and why his “Politics” remains a vital (and sometimes controversial) text:

Analyzing Existing Governments:

- Observation-First: Aristotle began by systematically examining real-world constitutions – Greek city-states, monarchies, neighboring empires – to identify their strengths and weaknesses.

- Classification: He famously categorizes governments along two axes:

- Who Rules?: One, Few, or Many (i.e., Monarchy, Aristocracy, Polity).

- Good vs. Corrupt Forms: Each has a corresponding ‘bad’ version – Tyranny, Oligarchy, Democracy (which at the time had negative connotations of mob rule).

The Ideal State:

- Not One-Size-Fits-All: Aristotle acknowledges no single best system for every circumstance. Factors like geography, population, and culture necessitate different approaches

- Aiming for the Good: His ideal focuses on enabling citizens to live fulfilling lives guided by virtue and reason.

- Debate over Form: Scholars argue whether his ideal is ultimately aristocratic, a mixed form, or focused on the broader civic good, even if the ruling class is small.

Key Concepts:

- Humans as Political Animals: Aristotle views us as inherently social, finding meaning in the community. The state isn’t just a contract but the natural arena for fulfilling our potential.

- Importance of the Middle Class: He believed a stable society requires a strong middle class, preventing extremes of wealth or poverty and reducing social conflict.

- Education for Citizenship: Citizenship isn’t just about rights and responsibility. Education should create individuals capable of good governance and active participation in civic life.

Controversial Ideas:

- Natural Hierarchy: While meritocracy plays a role in his ideal, he accepts certain inequalities. His views on slavery and the limited roles of women in society (based on his understanding of biology) are highly problematic from a modern view.

- Context is Key: Judging him solely by our standards is unfair. Yet, it demonstrates why political philosophy is always a debate, as even great thinkers are impacted by the assumptions of their time.

Legacy:

- Foundation of Political Science: Aristotle moved the study of politics from abstract idealism into comparative study, laying the groundwork for later analysis.

- Enduring Questions: He prompts us to question the purpose of government, the balance between individual good and community good, and the qualities we seek in leaders.

Let me know if you’d like to delve into:

- Arguments for or against specific government forms.

- Similarities/differences between Aristotle’s view of citizenship and modern ideas.

- His influence on later political thinkers.

Rhetoric and Poetics: Aristotle’s works explore persuasive communication, effective language use (Rhetoric), and the principles of tragedy and dramatic storytelling (Poetry).

Rhetoric:

- “Rhetoric may be defined as the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion.” – This defines the core of rhetoric as identifying and utilizing the most effective methods to convince an audience.

- “Of the modes of persuasion furnished by the spoken word, there are three kinds. The first kind depends on the personal character of the speaker; the second on putting the audience into a certain frame of mind; the third on the proof, or apparent proof, provided by the words of the speech itself.” – This outlines Aristotle’s three pillars of persuasion: ethos (credibility), pathos (emotion), and logos (logic).

- “The audience is the end and object of the speech.” – This emphasizes the importance of understanding and tailoring your message to the specific audience you’re addressing.

- “It is not enough to know what we ought to say; we must also say it as we ought.” – This highlights the importance of delivery and style in effective communication, not just the content of the message.

- “The greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor.” – Metaphor, for Aristotle, is not just a literary device but a way to illuminate complex ideas and connect with an audience on a deeper level.

Poetics:

- “Tragedy is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude… through pity and fear affecting the proper purgation of these emotions.” – This defines tragedy’s core purpose as evoking and resolving powerful emotions in the audience.

- “A whole is that which has a beginning, a middle, and an end.” – This outlines the importance of a unified and well-structured plot in dramatic storytelling.

- “Character is that which reveals moral purpose, showing what kind of things a man chooses or avoids.” – This emphasizes the importance of character development in revealing a character’s motivations and choices.

- “Poetry is finer and more philosophical than history; for poetry expresses the universal, and history only the particular.” – Aristotle argues that poetry, through its universal themes, offers deeper insights into human nature than historical accounts.

- “The plot, then, is the first principle, and, as it were, the soul of a tragedy.” – This highlights the primacy of the plot in creating a compelling and meaningful drama.

You’re spot on! Here’s why Aristotle’s explorations of rhetoric and poetics are still studied today:

Rhetoric: The Art of Persuasion

- Beyond Speechmaking: For Aristotle, rhetoric wasn’t just about fancy speeches but the ability to discern the persuasive means available.

- Three Main Appeals: He analyzed persuasion as having three main tools:

- Logos: Appealing to reason and logic

- Ethos: Building credibility and the speaker’s character

- Pathos: Evoking emotion in the audience.

- Not Just Good vs. Evil: Rhetoric is ethically neutral. It can be used for noble ends or to manipulate. Aristotle explores a full range of persuasive techniques.

Poetics: Analyzing Drama

- Focus on Tragedy: This work largely dissects tragedy, the dramatic form most highly valued by Athenian society at the time.

- Elements of Good Drama: Aristotle examines plot, character, diction (language), thought (the ideas it grapples with), spectacle, and music.

- Mimesis: A key concept is the idea of art as imitation. Great tragedy doesn’t just depict events but imitates human action in a way that reveals deeper truths about human nature.

- Catharsis: He theorized that experiencing pity and fear through tragedy can purge and ultimately benefit the audience.

Why These Matter Today:

Rhetoric:

- Unmasking Persuasion: Understanding Aristotle’s breakdown of appeals empowers us to analyze modern-day speeches, advertisements, and social media more critically.

- Building Effective Arguments: Even if you’re not delivering orations, building a logical, credible, and emotionally resonant case is valuable in numerous contexts.

Poetics:

- Timeless Storytelling: While focused on Greek drama, Aristotle’s analysis of plot structure, character development, and the power of language applies to modern storytelling in novels, film, and theater.

- Understanding Impact: Why do certain stories move us? Aristotle’s theories of catharsis and the aims of tragedy prompt reflection on the power of art to shape our understanding of ourselves.

Let me know if you’d like a deeper dive into…

- Specific examples of persuasive techniques in rhetoric

- Aristotle’s definition of a “tragic hero.”

- Debates about how to interpret his ideas on drama

Aristotle’s Later Life and Legacy

-

Athens Departure: After Alexander the Great’s death, anti-Macedonian sentiment flared in Athens. Aristotle left the city in 323 BCE to avoid persecution.

-

Death: He died in 322 BCE at the age of 62.

-

Enduring Influence: Aristotle’s works were preserved despite his death and became the cornerstone of philosophy during the Middle Ages. His ideas continue to be studied and debated even today.

Aristotle with a Bust of Homer by Rembrandt. Oil on canvas, 1653 (Wiki Image).

You’ve accurately summarized the key points of Aristotle’s later life and legacy! Here’s some additional context and detail about why his influence remains so profound:

Departure from Athens:

- Shifting Political Tides: Alexander’s death created a power vacuum. Aristotle, vulnerable due to Macedonian connections and potentially even accused of impiety for views clashing with traditional religion, wisely fled.

- Final Retreat: He spent his final year in Chalcis on the island of Euboea. The exact cause of his death at 62 is unknown, but it was likely due to natural causes.

Preservation and Rediscovery of Works:

- Not Immediately Famous: Other philosophical schools gained prominence centuries after his death. Some Aristotle texts were lost, and others survived only as fragmentary notes.

- Revived Interest: Roman scholars and later Islamic philosophers rediscovered his writings, translating and preserving them.

- Medieval Foundation: Through thinkers like Thomas Aquinas, Aristotle’s works were woven into the intellectual fabric of medieval Europe, impacting Christian theology and scientific thought.

The Breadth of Aristotle’s Impact:

- The Renaissance and Beyond: Renewed interest in classical texts during the Renaissance further solidified his status. His influence extends across:

- Science: While most of his specific theories were ultimately revised, his systematization of knowledge and the impetus for observation shaped Western scientific tradition.

- Philosophy: Metaphysics, ethics, logic, political theory… there’s hardly a branch of philosophy Aristotle didn’t touch, sparking debates that continue today.

- Arts: His ideas about rhetoric, poetics, and aesthetics influenced literary analysis and artistic practices.

Why His Legacy Endures:

- Not Just Right Answers: More than the specific conclusions he reached, it’s the depth of his questions about the fundamental nature of the world and how to live a good life that ensures continued engagement.

- Evolving Interpretations: Each era re-reads Aristotle through its lens. He remains relevant because thinkers continue to find new applications and arguments within his rich body of work.

Let me know if you’d like to explore:

- How his writings were lost and then rediscovered

- His impact on a specific historical period (e.g., the Middle Ages or the Renaissance)

- A modern debate influenced by Aristotelian ideas

Leonardo da Vinci’s History

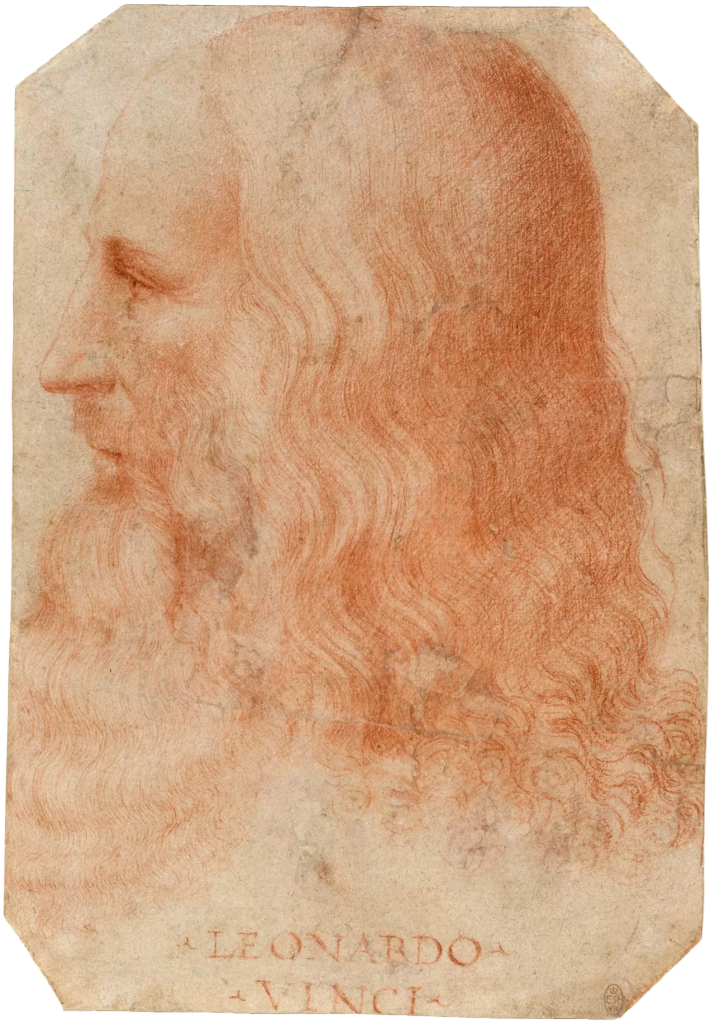

This portrait, attributed to Francesco Melzi, c. 1515–1518, is the only certain contemporary depiction of Leonardo (Wiki Image).

- “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.” Elegance and power often lie in refining something to its essential core.

- “Learning never exhausts the mind.” For da Vinci, pursuing knowledge is a lifelong, invigorating journey.

- “The noblest pleasure is the joy of understanding.” Discovering the workings of the world, whether natural or manmade, was deeply satisfying.

- “Time stays long enough for anyone who will use it.” Acknowledges that time can be a resource when used wisely, not merely something we passively experience.

- “Art is never finished, only abandoned.” This saying reminds us that the creative process is ongoing, and perfection may be elusive but can be strived for.

- “Water is the driving force of all nature.” Da Vinci recognized water’s fundamental role in shaping the world and sustaining life.

- “Where the spirit does not work with the hand, there is no art.” True artistry requires the union of intellectual thought and physical skill.

- “All our knowledge has its origins in our perceptions.” Emphasizing that our understanding of the world starts with observation and experience.

- “I have been impressed with the urgency of doing. Knowing is not enough; we must apply. Being willing is not enough; we must do.” Da Vinci valued turning ideas into action.

- “The human foot is a masterpiece of engineering and a work of art.” He was fascinated by the beauty and complexity of even the most ordinary things.

| Year | Age | Events & Developments | Polymathic Pursuits |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1452 | 0 | Born in Vinci, Republic of Florence (April 15th). The illegitimate son of a notary, Piero da Vinci, and a peasant woman, Caterina. | |

| 1460s | 10s | Shows early artistic talent. Receives basic education in reading, writing, and arithmetic. | – Develops a keen interest in nature and observation. |

| 1469 | 17 | Apprenticed to Andrea del Verrocchio, a leading artist in Florence. Begins training in painting, sculpture, and other arts. | – Exposed to diverse workshop activities, including painting, sculpture, metalworking, and engineering. |

| 1472 | 20 | Joins the painters’ guild of Florence. | – Begins to undertake independent commissions. |

| 1470s | 20s | – Continues to work in Verrocchio’s workshop. <br> – Produces early paintings, including Annunciation and Baptism of Christ. | – Develops his artistic skills and experiments with new techniques. <br> – Begins to explore anatomy through dissection. |

| 1482 | 30 | Moves to Milan to serve as engineer, artist, and architect for Duke Ludovico Sforza. | – Designs fortifications, weapons, and stage machinery. <br> – Paints Virgin of the Rocks and begins work on The Last Supper. |

| 1490s | 40s | – Continues his diverse work in Milan. <br> – Produces The Last Supper (1495-1498) and other paintings. <br> – Studies anatomy, mathematics, and engineering. <br> – Designs flying machines and other inventions. | – Writes extensively in his notebooks, recording observations, ideas, and inventions. |

| 1499 | 47 | Leaves Milan after the French invasion. Travels to Venice and other cities. | – Works as a military engineer and architect. |

| 1503 | 51 | Returns to Florence. Begins work on the Mona Lisa. | – Continues his artistic and scientific pursuits. <br> – Studies the flight of birds and designs flying machines. |

| 1506 | 54 | Returns to Milan under French patronage. | – Continues his work as an artist, engineer, and scientist. |

| 1513 | 61 | Moved to Rome under the patronage of Pope Leo X. | – Conducts anatomical studies and scientific experiments. |

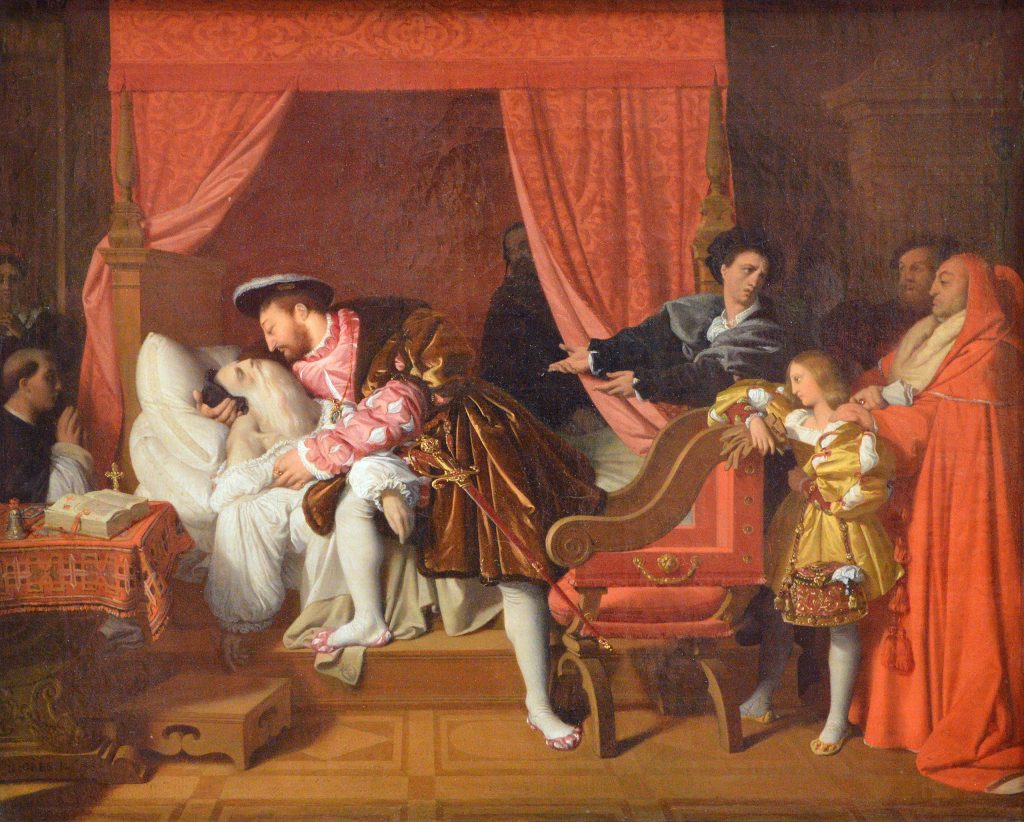

| 1516 | 64 | Moves to France at the invitation of King Francis I. Resides at Clos Lucé near Amboise. | – Continues his artistic and scientific work, though at a slower pace. |

| 1519 | 67 | Dies at Clos Lucé (May 2nd). |

Absolutely! Here’s a breakdown of Leonardo da Vinci’s fascinating history, covering his major life events, artistic works, and scientific endeavors:

Early Life and Apprenticeship

- Birth: Leonardo was born in 1452 in the village of Anchiano near Vinci, Republic of Florence (present-day Italy).

- Background: He was the illegitimate son of a prominent notary and a peasant woman, and his upbringing provided a blend of formal education and independent exploration.

- Apprenticeship with Verrocchio: Around age 14, Leonardo began a lengthy apprenticeship with the renowned artist Andrea del Verrocchio in Florence. This formative period exposed him to painting, sculpture, metalworking, and various technical skills.

Artistic Career and Achievements

- Florence and Milan: Leonardo established himself as a brilliant independent artist in Florence, but a desire for patronage led him to Milan, where he served the powerful Sforza family from 1482-1499.

- Iconic Works: This period saw the creation of some of his most famous masterpieces, including:

- The Last Supper: A revolutionary mural depicting the emotional turmoil of Jesus’ betrayal.

- Mona Lisa: This enigmatic portrait is famed for its subtle smile and masterful technique.

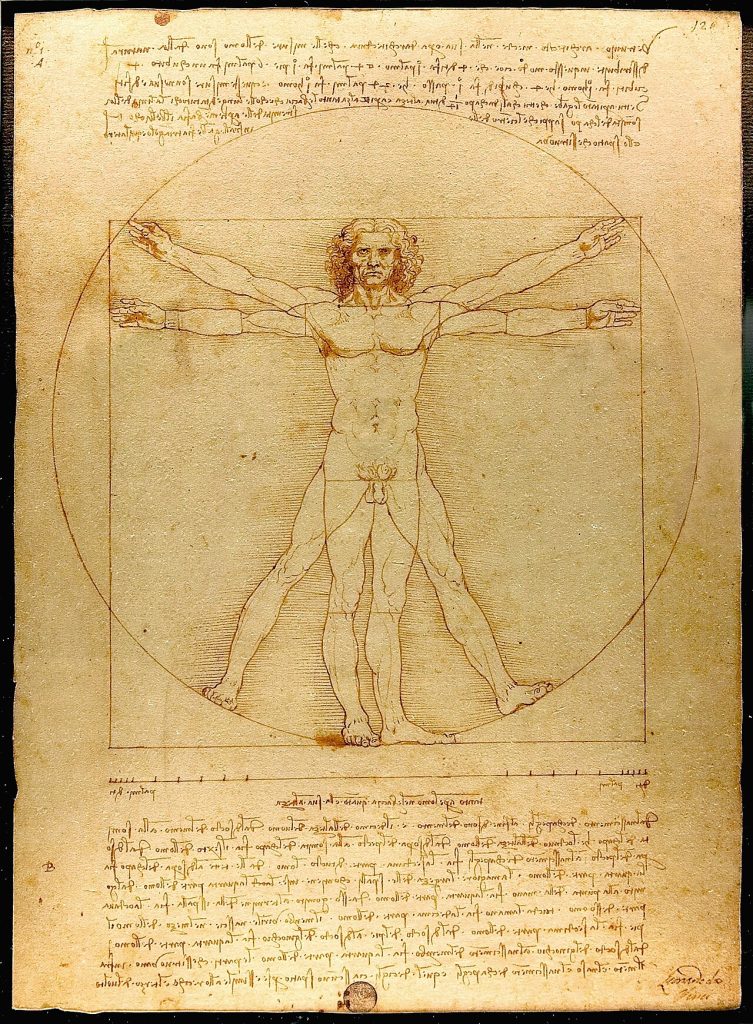

- Vitruvian Man: A drawing demonstrating artistic skill and a keen interest in anatomy and human proportions.

Scientific and Engineering Pursuits

- Insatiable Curiosity: Leonardo wasn’t just an artist but a polymath with limitless curiosity. He filled countless notebooks with observations, sketches, and ideas across disciplines.

- Subjects of Study: His investigations included:

- Anatomy: He dissected human bodies to advance his understanding of form and function.

- Engineering: Leonardo designed ingenious machines, including flying contraptions, war machines, and hydraulic systems.

- Nature: He observed birds, water flow, plants, and geology, seeking universal patterns.

Later Years and Legacy

- Patronage in France: In 1516, he moved to France under the patronage of King Francis I, where he lived out his final years.

- Death: Leonardo died in Amboise, France, in 1519, leaving an extraordinary legacy.

- A True Renaissance Man: He embodies the Renaissance ideal – a master artist, a brilliant scientific mind, and an insatiable seeker of knowledge in the full spectrum of human experience.

Let me know if you’d like more details on specific works, his scientific inquiries, or the cultural context of Renaissance Italy!

Leonardo da Vinci YouTube Video

- Decoding da Vinci | Full Documentary | NOVA | PBS by NOVA PBS Official:

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NGsUFvwgvCo

- Views: 6,696,608

- The Renaissance – The Age of Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci (1/2) | DW Documentary:

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BmHTQsxxkPk

- Views: 5,508,582

- The Genius of Leonardo da Vinci by CBS Sunday Morning:

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KJboCFa4iVQ

- Views: 1,558,037

- Leonardo da Vinci for Kids | Learn all about one of the most famous artists of all time by Learn Bright:

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mxEhLZ8tW3E

- Views: 300,068

- Leonardo da Vinci: Renaissance Artist & Inventor | Mini Bio | BIO by Biography:

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XjcJG0YQSds

- Views: 197,843

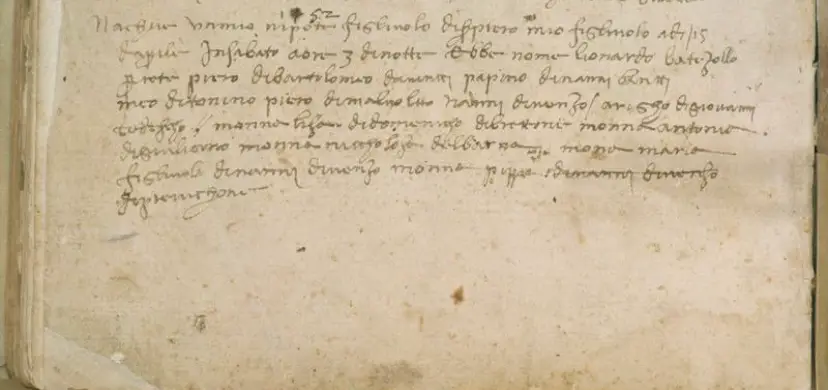

Early Life and Apprenticeship

-

Birth: Leonardo was born in 1452 in the village of Anchiano near Vinci, Republic of Florence (present-day Italy).

-

Background: He was the illegitimate son of a prominent notary and a peasant woman, and his upbringing provided a blend of formal education and independent exploration.

-

Apprenticeship with Verrocchio: Around age 14, Leonardo began a lengthy apprenticeship with the renowned artist Andrea del Verrocchio in Florence. This formative period exposed him to painting, sculpture, metalworking, and various technical skills.

Leonardo Da Vinci’s baptism record (Wiki Image).

The Baptism of Christ (1472–1475) by Verrocchio and Leonardo, Uffizi Gallery (Wiki Image).

Absolutely! Let’s dive deeper into Leonardo da Vinci’s early life and those crucial apprenticeship years that shaped his path:

Birth & Illegitimacy:

- Location: Anchiano, a small hamlet outside Vinci, provided a rural setting that was likely filled with natural wonders that sparked early curiosity.

- Social Impact: Being born out of wedlock would have some limitations. He couldn’t follow his father as a notary, but it likely freed him from a proscribed path.

- Father’s Influence: Ser Piero da Vinci was well-connected. He ensured Leonardo received a decent education in basic subjects like reading, writing, and mathematics.

The Upside of Informal Upbringing:

- Less Bookish, More Hands-On: He likely wasn’t immersed in the classics the same way a formal upper-class education would have offered. Instead, he learned through observation of the natural world and tinkering.

- Developing Skills: He may have helped in his father’s workshop with tasks needing drafting, measurements, and practical knowledge of materials.

- Freedom to Roam: The Tuscan countryside provided ample space for a curious mind to explore, fostering an appreciation for plants, animals, and the mechanics of natural phenomena.

Verrocchio’s Workshop: A Renaissance Powerhouse

- Not Just an Art Studio: Verrocchio’s workshop was a hub for everything from painting and sculpture to bronze casting, goldsmithing, and even engineering projects.

- Fellow Apprentices: Leonardo trained alongside future big names like Botticelli and Perugino, creating a competitive and collaborative environment.

- Breadth of Training: He mastered:

- Drawing & Painting: Anatomy, perspective, color theory

- Technical Skills: Chemistry for pigments, plasterwork, and even early mechanics.

Laying the Foundation:

- Beyond Specific Techniques: This period taught him how to learn. His notebooks start filling with sketches and observations – a habit persisting throughout his life.

- Renaissance Ideals: Verrocchio embodied the “uomo universale” ideal – an individual excelling in many fields. This, no doubt, shaped Leonardo’s insatiable thirst for knowledge.

Let me know if you want to know more about:

- Specific anecdotes about tasks he likely performed as an apprentice

- The vibrant artistic scene of Florence and how it influenced him

- Comparisons to how other Renaissance artists of the time were trained

Artistic Career and Achievements: Leonardo established himself as a brilliant independent artist in Florence. However, a desire for patronage led him to Milan, where he served the powerful Sforza family from 1482 to 1499.

Absolutely! Here’s a look at how Leonardo’s artistic career evolved, including his pivotal Milanese period:

Early Works in Florence:

- Emerging Talent: Works like the “Adoration of the Magi” (unfinished) and the “Annunciation” demonstrate his early mastery of perspective, composition, and expressive faces.

Adoration of the Magi, Leonardo da Vinci

- Ambitious but Restless: He had a reputation for being a perfectionist, often leaving projects incomplete as his interests shifted.

- Seeking Opportunities: Florence, an artistic center, was also crowded with talent. A powerful patron could provide stability and resources for his grand ambitions.

The Move to Milan:

- Duke Ludovico Sforza: Known as “Il Moro,” the Duke was an ambitious, power-hungry ruler eager to turn Milan into a cultural showpiece to enhance prestige.

- Appeal for Leonardo: Milan offered:

- Less Competition: Chance to be a bigger fish in a slightly smaller pond.

- Diverse Projects: Sforza needed art and engineering expertise for military and courtly spectacles.

- Potential Stability: Generous patronage in exchange for dedicated service.

Duke Ludovico Sforza

Milanese Masterpieces & More:

- The Last Supper (1495-1498): A revolutionary mural in both technique and emotional intensity, it remains one of his most famous works.

Last Supper, Leonardo da Vinci

- Mona Lisa (started around 1503): Likely begun in Florence, he continued this iconic portrait in Milan. Its enigmatic smile and masterful sfumato technique make it a timeless fascination.

Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci

- Beyond Painting: His time in Milan included:

- Designing elaborate festivals and theatrical productions

- Architectural studies and city planning proposals

- Military engineering sketches (though most were never realized)

The Fall of Sforza:

- Political Turmoil: Leonardo’s stable patronage disappeared when French forces invaded in 1499. From this point on, his life became more itinerant.

- Lasting Impact: The Milanese period showcases Leonardo’s ability to flourish when given support. It honed the blend of art and technical brilliance that makes him so unique.

Let me know if you want to delve into it.

- Analysis of a specific artwork’s techniques

- Leonardo vs. other artists working in Milan

- The misfortune of some projects, like the failed giant bronze horse for Sforza

The Last Supper: A revolutionary mural depicting the emotional turmoil of Jesus’ betrayal.

The Last Supper, Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan (c. 1492–1498) (Wiki image).

Absolutely! Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper” is a landmark achievement in art history, renowned for its artistic mastery and tragic fate. Here’s a deeper look at its revolutionary nature and enduring impact:

Breaking From Tradition:

- Composition: Unlike traditional depictions where figures sit flat on a background plane, Leonardo uses perspective to create a sense of depth, drawing the viewer into the scene.

- Focus on Emotion: The emphasis isn’t just on the figures and their reactions to Jesus’ announcement of betrayal. Each apostle displays a unique range of emotions – shock, disbelief, anger, and sorrow. This focus on human psychology was groundbreaking.

- Vanishing Point & Halo: The vanishing point, where perspective lines converge, is placed directly behind Jesus’ head, emphasizing his centrality. Leonardo eschewed the traditional gold leaf halo, using light and shadow to achieve a more naturalistic effect.

Technical Innovations:

- Experimental Techniques: The Last Supper wasn’t painted on traditional plaster walls but on a new drying technique directly onto the monastery refectory wall. Unfortunately, this proved unstable and contributed to the mural’s deterioration.

- Sfumato: Leonardo’s signature technique of using delicate layers of translucent glazes creates a hazy, dreamlike quality, adding depth and mystery to the scene.

A Work of Loss and Restoration:

- Deterioration and Restoration Efforts: The experimental technique and environmental factors led to rapid decay. The Last Supper has undergone numerous restoration efforts throughout the centuries, aiming to preserve what remains.

- Layers of History: Restorations reveal not just the brilliance of the original work but also offer a window into how art is preserved and interpreted across time.

Legacy of The Last Supper:

- Beyond Artistic Merit: It’s not just a beautiful painting but a powerful exploration of human emotions at a pivotal moment.

- Influence on Religious Art: Leonardo’s focus on psychological drama changed how artists depicted biblical scenes.

- An Enduring Enigma: The mystery surrounding the techniques used, the ongoing restoration efforts, and the scene’s emotional power all contribute to the mural’s enduring fascination.

Would you like to explore:

- In-depth analysis of specific aspects of the painting (composition, use of light and shadow, etc.)

- The scientific challenges of restoring the mural

- The Last Supper’s place within the broader context of Leonardo’s religious works?

Mona Lisa: This enigmatic portrait is famed for its subtle smile and masterful technique.

The Mona Lisa is digitally retouched to reduce the effects of aging; the unretouched image is slightly darker (Wiki Image).

Absolutely! The Mona Lisa, or La Gioconda as it is sometimes known, is one of the most famous paintings in the world, shrouded in mystery and fascination. Here’s a deeper look:

The Subject:

- Lisa Gherardini: The sitter is believed to be Lisa del Giocondo, wife of a wealthy Florentine merchant. However, there’s an ongoing debate about her true identity, adding to the painting’s allure.

- A Moment Captured: Leonardo didn’t just create a portrait; he captured a fleeting expression and a psychological depth rarely seen in art at the time.

The Technique:

- Sfumato: Leonardo’s signature technique of blurring lines and creating soft transitions between colors is masterfully employed. This gives the portrait an ethereal, almost lifelike quality.

- Subtle Smile: Mona Lisa’s enigmatic smile is the most iconic element. It’s barely there, yet it draws the viewer in, making them question their thoughts or feelings.

- Background Landscape: The rugged, dreamlike landscape behind Mona Lisa is just as captivating as her face. It adds another layer of mystery and depth to the work.

The Enigmatic Aura:

- The Smile’s Mystery: The exact nature of Mona Lisa’s smile has been debated for centuries. Is it happiness? Sadness? Amusement? Contempt? This ambiguity is a large part of what makes the painting so alluring.

- Stolen and Recovered: In 1911, the Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre Museum in Paris, causing a worldwide sensation. Two years later, it was recovered, further cementing its status as a global icon.

Cultural Impact:

- A Pop Culture Icon: The Mona Lisa has been reproduced and referenced countless times, from serious art criticism to commercial parodies.

- Symbol of Femininity: The painting symbolizes femininity and female empowerment, inspiring countless interpretations and reimaginings.

- Timeless Allure: The Mona Lisa’s enduring popularity speaks to its unique power to captivate and mystify audiences across centuries and cultures.

Would you like me to dive into…

- What theories about the painting’s symbolism and the identity of the Mona Lisa?

- The story of its theft and recovery?

- Leonardo’s use of specific artistic techniques in the portrait?

Vitruvian Man: A drawing demonstrating artistic skill and a keen interest in anatomy and human proportions.

Vitruvian Man (Wiki Image).

Absolutely! The Vitruvian Man is one of Leonardo da Vinci’s most recognizable and celebrated works. It embodies his fascination with the human form and genius in combining art and science.

The Drawing:

- Subject: A nude male figure in two superimposed positions, with arms and legs outstretched, both inscribed in a circle and a square.

- Inspiration: The drawing is based on the writings of the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius, who described the ideal proportions of the human body.

- Purpose: It studied human anatomy and proportion, exploring the mathematical relationships between different body parts. Leonardo believed that these proportions reflected divine harmony.

- Technique: The drawing is meticulously executed in pen and ink, demonstrating Leonardo’s mastery of anatomical detail and his ability to depict the human form with accuracy and beauty.

Significance:

- Renaissance Humanism: The drawing embodies the Renaissance ideal of man as the measure of all things, reflecting a renewed interest in classical knowledge and the human body.

- Symbol of Perfection: It’s often seen as a symbol of perfect proportions and the ideal human form, both physically and intellectually.

- Scientific Inquiry: The Vitruvian Man is also an example of Leonardo’s scientific approach to art, using observation and measurement to understand the natural world.

- Cultural Icon: The drawing has become a cultural icon, reproduced and referenced countless times in art, literature, and pop culture.

Further Exploration:

If you’re interested in learning more, you could explore:

- Leonardo’s anatomical studies: His meticulous drawings of muscles, bones, and organs reveal his deep understanding of the human body.

- The writings of Vitruvius: Understanding the source material will give you further insight into Leonardo’s interpretation and artistic vision.

- The Renaissance context: The Vitruvian Man reflects the broader cultural and intellectual currents of the Renaissance, where art and science intersected.

Let me know if you’d like to delve deeper into these areas!

Scientific and Engineering Pursuits: Leonardo wasn’t just an artist but a polymath with limitless curiosity. He filled countless notebooks with observations, sketches, and ideas across disciplines.

Anatomy: Leonardo dissected human bodies to advance his understanding of form and function.

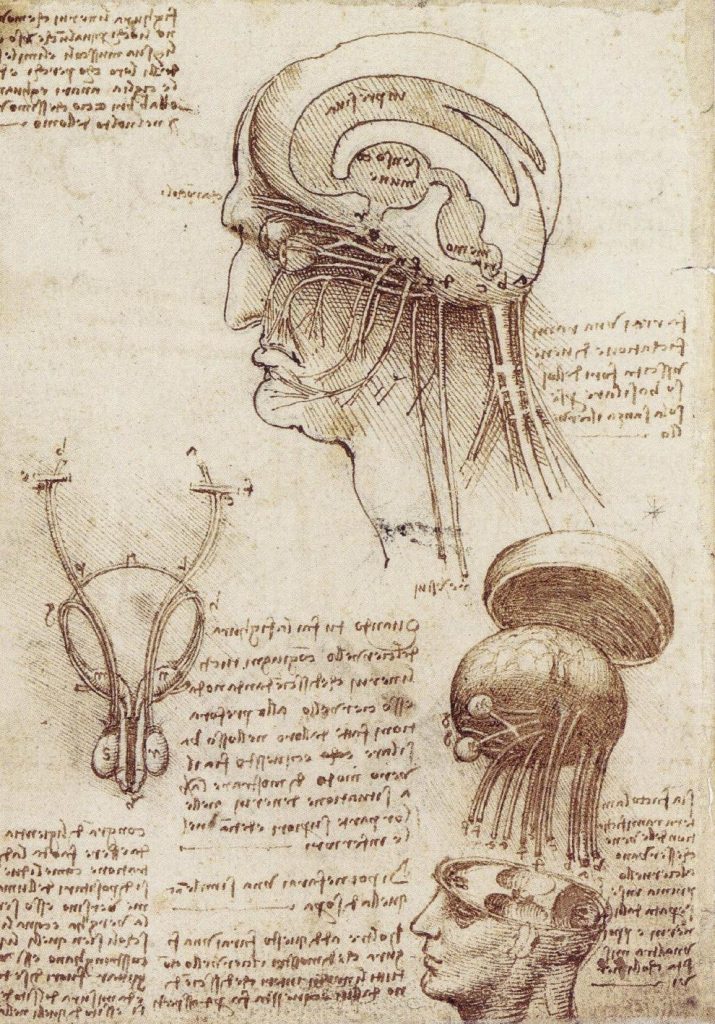

Leonardo’s physiological sketch of the human brain and skull (c. 1510) (Wiki Image).

Yes, that’s right! Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical studies were revolutionary for their time, and even by today’s standards, they stand out for their detail and accuracy.

Here’s a deeper look into his work:

Motivation:

- Beyond Artistic Pursuit: While his primary interest in anatomy stemmed from a desire to depict the human form accurately in his art, his curiosity went much further.

- The Human Machine: Leonardo was fascinated by the human body as a complex machine, driven to understand its inner workings, not just its external appearance.

- Challenging Tradition: Medieval anatomical knowledge was often based on animal dissections and ancient texts rather than direct observation of human bodies. Leonardo sought to challenge these traditional views and gain firsthand knowledge.

Methods:

- Personal Dissections: Leonardo dissected over 30 human cadavers, including men, women, and children, meticulously studying their skeletal, muscular, and organ systems.

- Detailed Drawings: He produced hundreds of anatomical drawings, often incorporating notes and observations on the function of different body parts. These drawings were incredibly detailed and accurate, far surpassing anything seen before.

- Cross-Sectional Views: Leonardo pioneered the use of cross-sectional drawings to depict the layers of the human body, giving a new perspective on its internal structures.

Key Discoveries:

- Accurate Heart Anatomy: He was the first to describe the heart’s four chambers and its role in pumping blood.

- Fetus in the Womb: He produced the first accurate drawings of a human fetus in the womb, based on dissections of pregnant women who had died.

- Spinal Column and Nerves: He made detailed observations of the spinal column and the nervous system, contributing to an early understanding of the brain and its functions.

- Musculoskeletal System: His drawings of muscles, bones, and joints were remarkably accurate, revealing his deep understanding of how the body moves and functions.

Legacy:

- Scientific Illustration: His anatomical drawings set a new standard for accuracy and detail, influencing medical illustration for centuries.

- Advanced Understanding: His work significantly advanced our human anatomy and physiology knowledge. While not published in his lifetime, his notebooks were rediscovered in later centuries, contributing to the development of modern medicine.

- A Visionary Ahead of His Time: Leonardo’s combination of scientific curiosity and artistic skill made him a true pioneer in anatomy. His meticulous studies paved the way for a deeper understanding of the human body and its intricate workings.

If you’d like, I can explore any of these areas further or provide more specific examples of Leonardo’s anatomical drawings and discoveries!

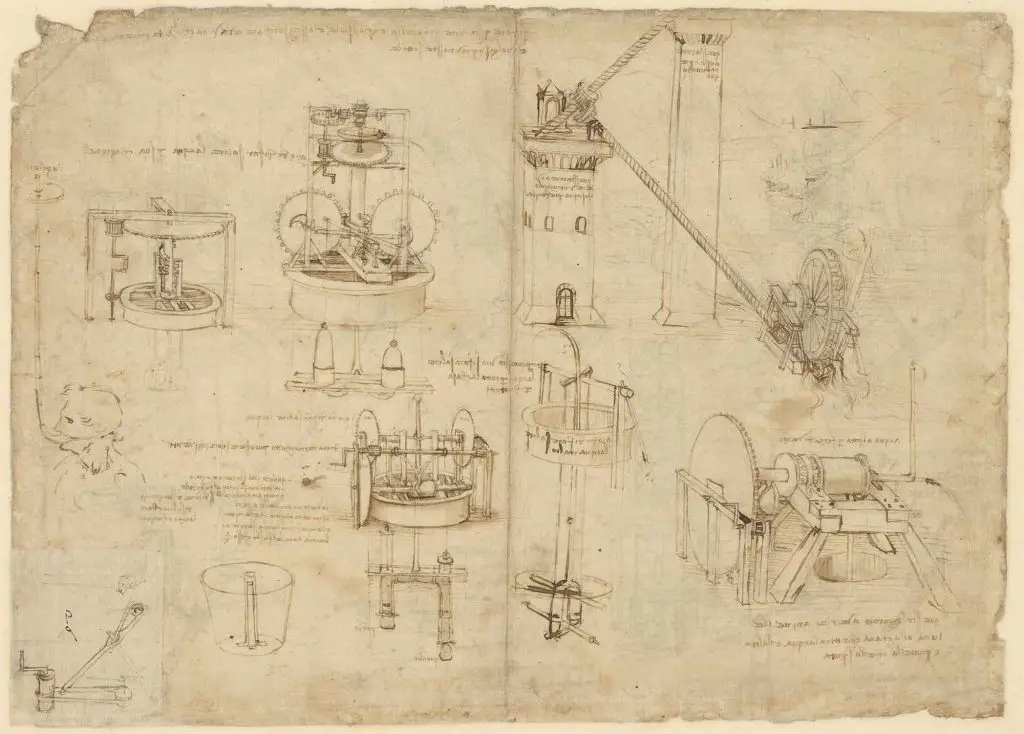

Engineering: Leonardo designed ingenious machines, including flying contraptions, war machines, and hydraulic systems.

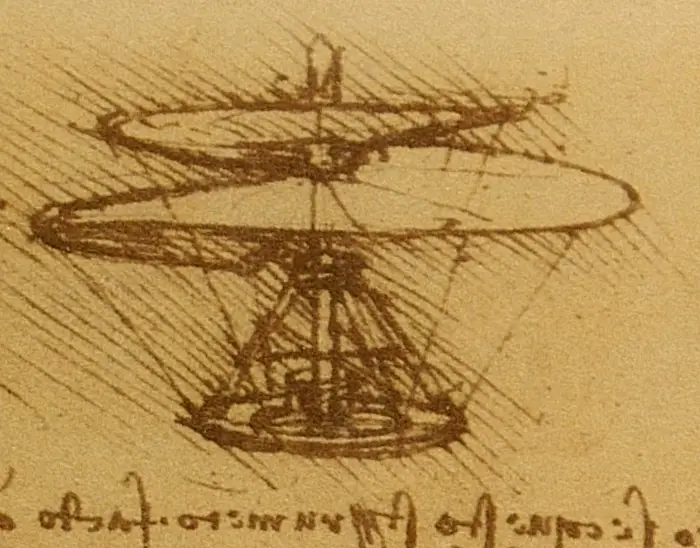

An aerial screw (c. 1489), suggestive of a helicopter, from the Codex Atlanticus (Wiki Image).

Yes, that’s right! Leonardo da Vinci’s engineering and mechanical drawings are a testament to his innovative mind and his drive to understand and improve upon the world around him.

Here’s a deeper look into his engineering pursuits:

Inspired by Nature:

- Leonardo keenly observed nature, studying bird flight, water flow, and other natural phenomena.

- He sought to replicate nature’s mechanisms in his designs, believing that nature had already solved many engineering challenges.

- This biomimicry is evident in his designs for flying machines, inspired by birds’ wings, and his hydraulic systems, inspired by the movement of water.

Diverse Range of Inventions:

-

Flying Machines: He envisioned various flying machines, including:

- Ornithopter: A human-powered aircraft with flapping wings, mimicking bird flight.

- Glider: A design with fixed wings for gliding.

- Parachute: A device to safely descend from heights.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Ornithopter

-

War Machines: He designed various military inventions, including:

- Armored car: A precursor to modern tanks.

- Giant crossbow: A powerful weapon for sieges.

- Multi-barreled cannons: To increase firepower on the battlefield.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Multibarreled Cannons

-

Hydraulic Systems: He explored the power of water and designed various hydraulic machines, such as pumps, cranes, and canals.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Hydraulic System -

Other Ingenious Devices: His notebooks contain drawings for:

- Self-propelled cart: Considered a precursor to the modern automobile.

- Diving suit and underwater breathing apparatus: For exploring the depths of the sea.

- Revolving bridge: A portable bridge for military use.

- Clockwork mechanisms: Including gears, escapements, and even a rudimentary robot.

Ahead of His Time:

- Most of Leonardo’s designs were conceptual and never built during his lifetime.

- The technology and materials available in the 15th and 16th centuries were not advanced enough to realize his visionary ideas.