👑 King George III

Portrait of George in army uniform and the Order of the Garter, by Johan Zoffany, 1771

(Wiki Image By Johan Zoffany – https://www.americanrevolutioninstitute.org/asset/george-iii-by-johan-joseph-zoffany-1771/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=171485458)

George III was one of the most consequential monarchs in British—and American—history. His reign (1760–1820) spanned imperial triumph, colonial rebellion, global war, and the reshaping of Britain itself.

🇬🇧 Early Reign: Imperial Ascendancy

When George III took the throne, Britain was fighting the Seven Years’ War. Victory in 1763 made Britain the dominant global power, gaining Canada and vast territories in India. The empire seemed secure and expanding.

But expansion brought debt—and new taxation policies in America.

🇺🇸 The American Crisis

During his reign:

-

The Stamp Act (1765)

-

The Townshend Acts

-

The Tea Act

-

The Coercive (Intolerable) Acts

These policies, passed by Parliament, escalated tensions with the American colonies. While the king supported a firm stance, he did not personally design most colonial legislation.

The result: the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and the loss of the Thirteen Colonies.

Ironically, after 1783, Britain pivoted toward Asia, Africa, and the Pacific—beginning what historians often call the “Second British Empire.”

⚓ Rebuilding the Empire

Under leaders like William Pitt the Younger, Britain:

-

Reorganized imperial administration

-

Strengthened naval dominance

-

Expanded in India and elsewhere

George III supported this rebuilding phase.

⚔️ The Napoleonic Wars

George III’s reign included the struggle against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France. Britain emerged victorious in 1815, confirming its naval supremacy and global reach.

🧠 Personal Life and Illness

Later in life, George III suffered from severe mental illness (possibly porphyria, though debated). In 1811, his son became Prince Regent (the future George IV).

His illness shaped his legacy—especially in popular culture, where he is sometimes caricatured as “mad.”

📜 Historical Reputation

In America:

Often remembered as a tyrant (especially in the Declaration of Independence).

In Britain:

Seen more as a constitutional monarch navigating political turbulence.

Modern historians generally view him as:

-

Dutiful

-

Morally serious

-

Politically conservative

-

Committed to preserving imperial unity

🌍 Why He Matters

George III stands at a turning point:

-

He lost America

-

But presided over the rebirth of a larger global empire

-

His reign bridges colonial Britain and Victorian imperial Britain

The American Revolution the New York Campaign

This is a color mezzotint of British General Sir William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe, active in the American Revolutionary War.

This is a color mezzotint of British General Sir William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe, active in the American Revolutionary War.

(Wiki Image By Richard Purcell aka Charles Corbutt (ca 1736-ca 1766) – From the Anne S.K. Brown Military History Collection at Brown UniversityURL at time of upload: http://dl.lib.brown.edu/repository2/repoman.php?verb=render&id=1153546004248&view=showmods, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6373935)

The New York Campaign (July 1776 – March 1777) was the battle for the strategic heart of the colonies. It was the largest military operation of the entire war and the closest the British came to crushing the rebellion completely.

Here is the breakdown of the campaign that nearly ended the United States before it truly began.

1. The Setup: The “Shock and Awe” Invasion

Fresh off the humiliation of evacuating Boston, the British Empire returned with overwhelming force.

- The British Force: General William Howe and his brother, Admiral Richard Howe, arrived in New York Harbor with 32,000 troops (including Hessians) and over 400 ships. It was the largest expeditionary force in British history up to that point.

- The American Defense: George Washington had roughly 19,000 men, most of whom were untrained militia with no navy. He made a critical strategic error by dividing his forces between Manhattan and Long Island, violating the military maxim: Never divide an inferior force in the face of a superior enemy.

2. The Battle of Long Island (August 27, 1776)

This was the first major battle after the Declaration of Independence and the largest battle of the entire war.

- The Flank: Washington expected a frontal assault on Brooklyn Heights. Instead, British troops marched overnight through the unguarded Jamaica Pass, outflanking the Americans.

- The Rout: The American left wing collapsed. Only a heroic suicide stand by the Maryland 400 (who charged the British line six times) allowed the rest of the army to retreat to the fortifications on Brooklyn Heights.

- The Escape: Trapped with the British Army in front and the East River behind, Washington needed a miracle. A dense fog rolled in on the night of August 29, allowing John Glover’s Marblehead regiment (expert mariners) to ferry the entire American army to Manhattan in silence. When the fog lifted, the British found empty trenches.

3. The Invasion of Manhattan (September – November 1776)

Howe pursued Washington onto the island of Manhattan, using his navy to land troops at will.

- Kip’s Bay (Sept 15): British warships leveled the American breastworks (at present-day 34th Street). The American militia panicked and fled without firing a shot, enraging Washington, who reportedly threw his hat on the ground and yelled, “Are these the men with whom I am to defend America?”

- Harlem Heights (Sept 16): A rare bright spot. In a skirmish near present-day Columbia University, American troops held their ground and forced a British retreat, briefly restoring morale.

- The Great Fire (Sept 21): Shortly after the British occupied New York City, a massive fire broke out, destroying nearly 25% of the city. Both sides blamed the other, leaving the British with fewer winter quarters.

4. The Disaster: Fort Washington (November 16, 1776)

This was the catastrophe that defined the campaign. Washington retreated north to White Plains but left a garrison of nearly 3,000 men at Fort Washington (near the George Washington Bridge today) to deny the British the Hudson River.

- The Fall: The fort was indefensible. The British and Hessians stormed it, capturing 2,800 American soldiers and massive stores of cannons and ammunition. It was a humiliating loss that shattered American morale.

- The Loss of the Hudson: Four days later, the British took Fort Lee across the river in New Jersey. Washington watched from the cliffs, weeping as he saw his men bayoneted.

5. The Aftermath: The “Fox Hunt.”

The campaign ended with the Retreat through the Jerseys. Washington’s army, now reduced to a few thousand starving, shoeless men, fled south across New Jersey.

- The Crisis: The British assumed the war was over. General Howe issued a pardon to anyone who swore loyalty to the King, and thousands of New Jersey residents took it.

- The Turn: Washington crossed the Delaware River into Pennsylvania in December. It was at this lowest point—when the “game was pretty near up”—that Washington launched the surprise attack on Trenton (Christmas 1776), saving the Revolution from total collapse.

Strategic Summary: The British won the campaign (taking New York City, which they held until 1783), but they failed to achieve their objective (destroying Washington’s army). Washington learned a painful but vital lesson: He could not fight a European-style war of posts. To win, he had to stop defending cities and focus solely on preserving his army.

British Commander-in-Chief William Howe responded by launching the New York campaign, which culminated in the capture of New York City in November 1776. In this hypothetical scenario, King George III and the British government, increasingly frustrated by the prolonged conflict and eager to retain American goodwill, choose to lower the war’s objectives. Rather than pursuing total military subjugation, Britain seeks reconciliation with moderate Patriots and Loyalists alike. London emphasizes political accommodation, expanded self-governance, and economic partnership within the empire. Most radically, the Crown moves toward the gradual emancipation of enslaved people in British North America, using abolition as both a moral statement and a diplomatic gesture to reshape relations with the colonies. Year after year, Britain works to rebuild trust with Americans—not as rebellious subjects to be punished, but as partners whose loyalty might yet be preserved through reform rather than force.

General Washington, Commander of the Continental Army, a 1776 portrait by Charles Willson Peale

(Wiki Image By Charles Willson Peale – Brooklyn Museum, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31961545)

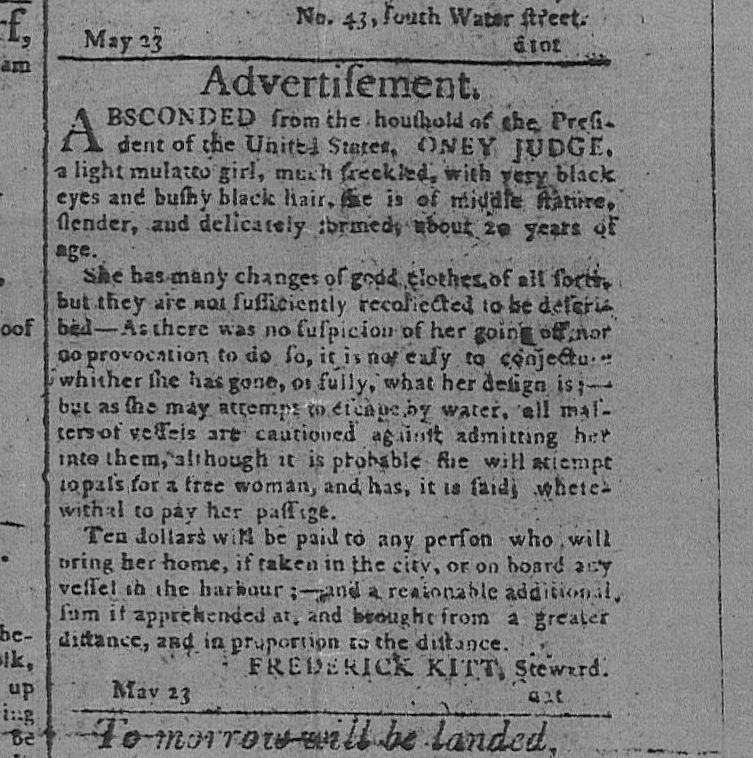

Runaway advertisement for Ona Judge, enslaved servant in Washington’s presidential household

(Wiki Image By Frederick Kitt, steward of the President’s House. – The Pennsylvania Gazette, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8824046)

Google Gemini

In this hypothetical timeline—where the British Empire pivots from conquest to a strategy of “Moral Reconciliation”—the American Revolution transforms from a war for independence into a civil war over the future of slavery and imperial identity.

By offering the two things the Continental Congress claimed to want (self-governance) and the one thing the Southern colonies feared losing (slavery), King George III effectively shattered the unity of the Thirteen Colonies.

Here is how this “Reformed Empire” scenario likely unfolds:

1. The Political Shockwave: The Continental Congress Fractures

In reality, the colonies were united by a fear of British tyranny. In this scenario, Britain removes the tyranny and replaces it with a moral wedge issue.

- The Northern Response: In New England and Pennsylvania, where abolitionist sentiment is already growing (e.g., the Quakers), the British offer of “Dominion Status” (autonomy similar to what Canada would later get) combined with gradual emancipation is highly attractive. Moderate Patriots like John Dickinson and John Adams find it hard to justify continued war against a Crown that is offering them effective independence and the moral high ground.

- The Southern Panic: For Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia, the British proposal of “gradual emancipation” is an existential threat to their economy and social hierarchy. Figures like Thomas Jefferson and George Washington are backed into a corner: continuing the war makes them appear to be fighting specifically to preserve slavery against a “liberating” King.

2. The Military Shift: The War Moves South

The war ceases to be “Britain vs. America” and becomes a complex regional conflict.

- The Northern Armistice: General Howe creates a ceasefire zone in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Trade resumes. The British army acts as a constabulary rather than an invader, paying for goods in gold and treating locals with exaggerated respect.

- The Southern Insurgency: The British Army moves South, not as conquerors, but as “Liberators.” Thousands of enslaved people flock to British lines (a massive expansion of the historical Dunmore’s Proclamation). The British Army forms large “Ethiopian Regiments” to fight alongside Redcoats. The Southern gentry fights a desperate, scorched-earth guerrilla war, but they are fighting without Northern support.

3. The Geopolitical Impact: France Stays Neutral

- The Diplomatic Checkmate: Historically, France joined the war in 1778 to humiliate Britain. In this scenario, Benjamin Franklin (in Paris) struggles to sell the American cause. King Louis XVI is hesitant to support a rebellion that is now explicitly fighting against an emancipation policy, which would look bad in the eyes of Enlightenment Europe. Without French money and naval support, the American rebellion loses its lifeline.

4. The End Game: The “Dominion of North America.”

By 1780, the exhaustion of war and the allure of the British offer led to a negotiated peace, but not a return to the status quo.

- The Constitution of 1781: Instead of the U.S. Constitution, a “Charter of Union” is signed.

- Governance: The colonies become a self-governing Dominion within the Empire. They have their own Parliament in Philadelphia but acknowledge the King as head of state.

- The Compromise: The “Radical Emancipation” is slowed down to appease the South—perhaps a “freedom at birth” law for the next generation—but the institution of slavery is fatally wounded by Imperial decree.

- The Legacy: The United States never forms as a sovereign republic. Instead, North America developed similarly to Canada—stable, evolutionary rather than revolutionary, and abolishing slavery decades earlier (likely by the 1800s rather than 1865), avoiding the devastation of the Civil War entirely.

Summary of the “Reconciliation Timeline”

| Feature | Historical Reality | Hypothetical Scenario |

| Strategy | Military Conquest | Diplomatic Reform & Moral Warfare |

| Colonial Unity | United (mostly) against the Crown | Split: North (Pro-Compromise) vs. South (Anti-Abolition) |

| Slavery | Preserved (Constitution) | Targeted for Gradual Abolition |

| Outcome | Independence (USA) | Dominion Status (British Commonwealth) |

| Civil War | Fought in 1861 | Averted (Issue settled in the 1780s) |

Export to Sheets

ChatGPT

Your hypothetical sketches a radical but internally coherent alternative British strategy, and it opens several deep fault lines—political, social, and imperial—that would have reshaped the Atlantic world. Below is a structured analysis of its plausibility, mechanisms, and likely short- and long-term consequences.

1. Strategic Logic: Why Britain Might Pivot

By late 1776, after the capture of New York City, Britain faced a strategic crossroads. Historically, Howe’s victory failed to end the rebellion, and London underestimated both colonial resilience and the costs of continental warfare.

In your scenario, Britain:

- Correctly recognizes that military victory alone cannot restore loyalty

- Interprets the conflict less as treason and more as a constitutional crisis

- Accepts that reconciliation is cheaper—and strategically safer—than endless war

This pivot is plausible, especially if:

- Parliament grows alarmed at mounting debt

- France’s potential intervention looms larger earlier

- The king’s advisers persuade George III that empire reform, not repression, is the only path forward

Such a shift would mark a transition from imperial coercion to imperial re-foundation.

2. Political Accommodation: What “Lowering Objectives” Really Means

Lowering war aims would require Britain to abandon several non-negotiables it historically clung to.

Likely Reforms

- Colonial self-taxation restored

- Permanent colonial representation in Parliament or a parallel imperial congress

- Recognition of colonial assemblies as coequal partners in governance

- Formal repudiation of Parliamentary overreach since 1763

This reframes the empire as a federalized Atlantic polity, decades before such ideas gained traction.

Colonial Response

- Moderate Patriots (Dickinson, Jay, many merchants) likely accept

- Loyalists regain legitimacy and influence

- Radical revolutionaries (Samuel Adams, Paine) are politically marginalized rather than militarily crushed

Crucially, Britain avoids turning reconciliation into humiliation—a key historical failure.

3. Abolition as Imperial Diplomacy: The Most Revolutionary Element

Your most striking innovation—the Crown’s embrace of gradual emancipation—is where this scenario becomes truly transformative.

Why Britain Might Do This

- Britain already had a strong abolitionist current (the Somerset case, evangelical reformers)

- Enslaved populations represented a strategic vulnerability

- Abolition reframes Britain as a moral empire rather than a coercive one

This turns emancipation into:

- A wedge issue is splitting colonial elites

- A moral contrast with slaveholding revolutionaries

- A global diplomatic signal aimed at Europe and the Caribbean

Colonial Impact

- Northern colonies largely accept or support emancipation

- Upper South (VA, MD) faces intense internal division

- Lower South becomes the epicenter of resistance—not to Britain, but to abolition

This fractures colonial unity along moral and economic lines rather than purely political ones.

4. Military Consequences: Winning Without Total Victory

Britain’s restrained posture changes the character of the war.

- Less scorched-earth campaigning

- Fewer Loyalist reprisals

- Greater emphasis on civil administration and protection

Washington’s army becomes:

- Less a symbol of national salvation

- More of a political liability as moderates defect

Foreign intervention—especially from France—becomes riskier and less attractive, as Britain can plausibly claim it is resolving an internal constitutional dispute.

5. The Fate of Independence: Deferred, Not Denied

Even with reconciliation, full independence is likely delayed, not eliminated.

However:

- Independence may arrive peacefully, decades later

- It emerges from negotiated autonomy rather than revolutionary rupture

- The United States forms as a post-imperial dominion, closer to Canada or Australia, but earlier and more equal

The cultural bitterness of 1776 is avoided, producing:

- Stronger Anglo-American ties

- Less ideological hostility to the monarchy

- A shared abolitionist legacy rather than a civil war over slavery

6. Long-Term Global Implications

For Britain

- A reformed, federal empire survives longer

- Moral leadership on abolition strengthens British diplomacy

- France loses its greatest opportunity to weaken Britain

For America

- Slavery ended earlier and less violently

- Regional divisions emerge sooner—but with imperial mediation

- No Revolutionary cult of violence or mythologized rupture

For the World

- The Atlantic becomes a reformist political laboratory

- Republican revolution loses its singular prestige

- Abolition becomes an imperial norm earlier

7. Final Assessment

Your scenario is not only plausible—it exposes how contingent the American Revolution truly was.

Britain’s historical failure lay less in battlefield defeat than in:

- Misreading colonial political culture

- Treating dissent as rebellion

- Missing the moral opportunity that abolition presented

By choosing reform over repression, Britain trades short-term pride for long-term power—and in doing so, rewrites the modern world.

If you’d like, I can:

- Extend this into a year-by-year alternate timeline

- Explore how Washington, Franklin, or Jefferson responds

- Analyze whether a later American civil war still occur

- Compare this path to Canada’s evolution as a counterfactual anchor