Egyptian Pyramids, Karnak Temple, Valley of the Kings, Abu Simbel, and Great Sphinx Compared: Egyptian Engineering, Architecture, Astronomy, and Art

The Egyptian monuments of the Pyramids, Karnak Temple, Valley of the Kings, Abu Simbel, and the Great Sphinx represent some of the most extraordinary achievements of ancient Egyptian engineering, architecture, astronomy, and art. Each site embodies unique elements of Egyptian society, beliefs, and technical skill, and together, they reflect the evolving complexity of Egypt’s cultural legacy.

Egyptian Engineering

- Pyramids: The construction of the pyramids, particularly the Great Pyramid of Giza, showcases the advanced engineering capabilities of ancient Egyptians. Built precisely and aligned with the cardinal points, the Great Pyramid comprises approximately 2.3 million limestone blocks weighing several tons. Its construction required sophisticated knowledge of quarrying, transportation, and labor organization.

- Karnak Temple: Engineering at Karnak involved constructing massive columns, obelisks, and pylons. The Great Hypostyle Hall features 134 towering columns requiring complex moving, erecting, and aligning techniques. Large stones were transported over long distances and positioned with such precision that they have withstood millennia.

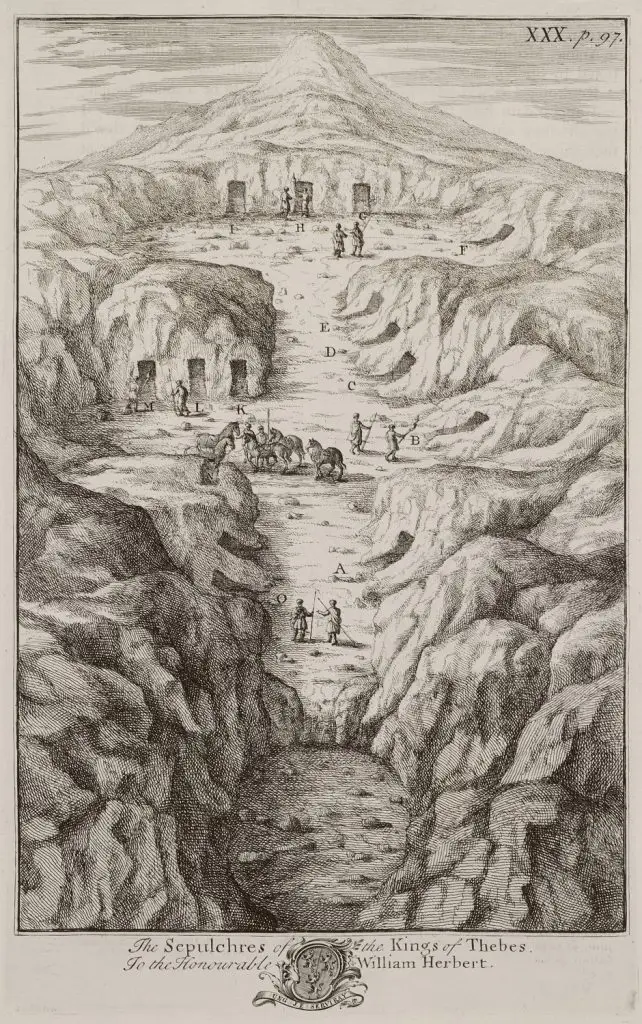

- Valley of the Kings: Engineering efforts in the Valley of the Kings focused on carving tombs deep into rock cliffs to protect pharaohs’ burial sites from looting and environmental damage. These tombs required careful planning, structural support within the mountain, and an understanding of ventilation to protect delicate artwork.

- Abu Simbel: Built by Ramses II, Abu Simbel’s engineering marvel lies in its precise orientation. Twice a year, sunlight illuminates the inner sanctuary, lighting up statues of Ramses and the gods but leaving Ptah, the god of darkness, in shadow. This alignment was calculated with remarkable accuracy.

- Great Sphinx: Carved from a single limestone outcrop, the Great Great Sphinx of Giza combines engineering with artistry. Its large scale required careful planning to avoid structural collapse and erosion, and it shows an advanced knowledge of stone working and preservation.

Egyptian Architecture

- Pyramids: The pyramids evolved from more superficial mastaba structures to true pyramids, reaching their architectural peak at Giza. The shape of the pyramid was a symbolic design, representing the primordial mound from which Egyptians believed life emerged. The architectural layout, with chambers and passageways, reflects an understanding of geometry and precision.

- Karnak Temple: Karnak is an example of architectural layering, with additions by successive pharaohs over centuries. Its layout includes grand entrance pylons, colossal columns, and large open courtyards. The temple’s architecture also features axial alignment, creating a processional route from the river to the inner sanctuaries.

- Valley of the Kings: The tomb architecture in the Valley of the Kings is unique because it is primarily underground. This design, often consisting of long corridors and multiple chambers, created a hidden, protective environment for the pharaoh’s journey to the afterlife. The architectural style here focuses on durability, security, and elaborate interior decoration.

- Abu Simbel: The architecture of Abu Simbel combines large-scale rock-cut facades with interior sanctuaries. The main temple is famous for its four colossal statues of Ramses II, which flank the entrance, showcasing monumental sculpture as an architectural feature. Abu Simbel reflects functional and symbolic design, built on Egypt’s southern border to demonstrate Ramses II’s power over Nubia.

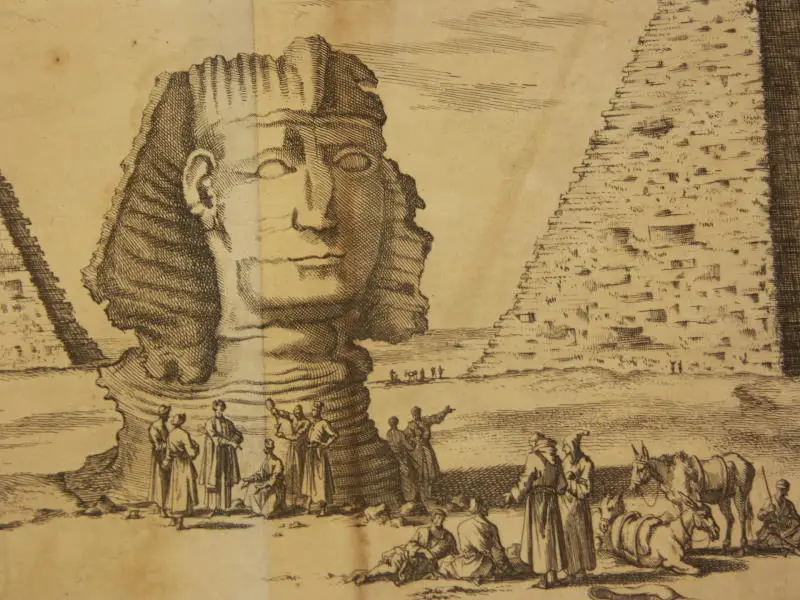

- Great Sphinx: One of the world’s oldest monumental sculptures, the Great Sphinx combines architecture and sculpture in its design. Its position near the pyramids indicates it may have served as a guardian of the necropolis and likely held symbolic significance related to the pharaoh’s role as a protector.

Egyptian Astronomy

- Pyramids: The alignment of the Great Pyramid’s sides with the cardinal points (north, south, east, and west) demonstrates an advanced understanding of astronomy and geography. The pyramid’s orientation likely reflects the Egyptians’ desire to link the pharaoh’s soul to the North Star, symbolizing eternity. This precision suggests that the builders used astronomical observations to guide construction.

- Karnak Temple: Astronomy influenced Karnak’s layout, especially during the Opet Festival, which celebrated the annual Nile flooding that aligned with celestial events. Temples were often aligned with specific stars or celestial events. Karnak’s orientation and processional paths connected the earthly and divine realms, emphasizing the cosmic order central to Egyptian cosmology.

- Valley of the Kings: Though the Valley of the Kings does not have apparent astronomical alignment, the tomb paintings and texts reference celestial themes, such as the journey of the sun god Ra through the underworld. Many tombs depict the night sky and use star maps as symbolic guides for the pharaoh’s journey in the afterlife.

- Abu Simbel: The orientation of Abu Simbel is one of the most well-documented examples of astronomical alignment. The sun illuminates the temple’s inner sanctuary twice yearly, suggesting that Egyptian architects understood solar movements and could integrate them into its construction.

- Great Sphinx: The Great Sphinx has been linked to astronomical symbolism, with some researchers suggesting it faces east to greet the sunrise and might have had associations with the solar cycle. Its lion’s body may also symbolize the constellation Leo, aligning with the Egyptians’ solar worship practices.

Egyptian Art

- Pyramids: The art within the pyramids is relatively sparse, as the Great Pyramid and others were originally devoid of decorative carvings or paintings. However, later pyramids, such as those at Saqqara, contained Pyramid Texts—hieroglyphic inscriptions on the walls detailing religious spells for the pharaoh’s protection in the afterlife. Art here was minimalistic but deeply symbolic.

- Karnak Temple: Karnak’s walls and columns are covered with intricate carvings and hieroglyphics depicting religious rituals, military conquests, and the divine status of the pharaohs. Karnak’s art is monumental, and it served not only decorative purposes but also conveyed political messages and spiritual themes through its immense scale and vivid depictions of gods.

- Valley of the Kings: The tombs in the Valley of the Kings contain some of the finest art in ancient Egypt, with vibrant wall paintings illustrating scenes from the Book of the Dead, Amduat, and the Book of Gates. These texts depict the pharaoh’s journey through the underworld and interactions with gods, and the art is detailed and rich in color, showing a high degree of artistry and religious symbolism.

- Abu Simbel: The art at Abu Simbel is both grand and precise. The colossal statues of Ramses II display idealized features that convey his divinity and power. Inside, the walls depict scenes of Ramses making offerings to the gods and triumphing in battle, reinforcing his image as a warrior and divine ruler. The art is characterized by its monumental scale and detailed execution.

- Great Sphinx: The Great Sphinx is an architectural and artistic masterpiece. A fusion of human and lion, the Great Sphinx represents a blend of art and symbolism, embodying the lion’s strength and the pharaoh’s wisdom. Although eroded, its craftsmanship is evident, particularly in its facial features, which display the distinct artistic style of the Old Kingdom.

Summary Comparison Table

| Monument | Engineering | Architecture | Astronomy | Art |

| Pyramids | Advanced quarrying, transport, and precision in stone alignment; the Great Pyramid was built with ~2.3 million limestone blocks | Monumental geometric shape (true pyramids), symbolic of the primordial mound; complex interior layout | Aligned with cardinal points, intended to link the pharaoh’s soul to the North Star and eternity | Minimalistic decoration, but some have Pyramid Texts (hieroglyphic spells) for afterlife guidance |

| Karnak Temple | Massive columns and pylons; extensive additions by multiple pharaohs over centuries | Axial layout, grand processional route; multiple pylons, open courtyards, and hypostyle hall | Linked to solar festivals like the Opet, processional routes aligned with celestial events | Intricate carvings and hieroglyphics depicting gods, rituals, and pharaohs’ divine status |

| Valley of the Kings | Rock-cut tombs designed for security; complex corridors carved into cliffs for stability | Subterranean tombs with elaborate chambers for pharaohs; protected setting within cliffs | Tomb decorations feature star maps, underworld depictions, and symbols guiding the soul | Vivid, detailed wall paintings depicting the journey to the afterlife and encounters with deities |

| Abu Simbel | Rock-cut facades with precise solar alignment in the inner sanctuary | Monumental rock-cut temple with colossal statues; inner sanctuary for deities and pharaoh | Solar alignment illuminates the inner sanctuary twice a year, highlighting statues of Ramses and gods | Colossal statues of Ramses; interior carvings showing battles, offerings, and divine reverence |

| Great Sphinx | Carved from a single limestone outcrop, it blends sculpture with architecture. | Guardian position near the pyramids, symbolizing protection; a fusion of a lion and a human figure | Faces east, symbolically linked to the solar cycle; may connect to the constellation Leo | Monumental sculpture of lion-man symbolizing strength and wisdom; fine craftsmanship in features |

Each monument reveals the Egyptians’ advanced skills and deep understanding of cosmic order, spiritual symbolism, and artistic expression. Together, they are a testament to the enduring legacy of ancient Egyptian civilization in fields as varied as architecture, astronomy, engineering, and art.

Egyptian Pyramids History

A view of the Giza pyramid complex from the plateau to the south of the complex. From left to right, the three largest are the Pyramid of Menkaure, the Pyramid of Khafre, and the Great Pyramid of Giza. The three smaller pyramids in the foreground are subsidiary structures associated with Menkaure’s pyramid.

(Wiki Image By Ricardo Liberato – All Gizah Pyramids, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2258048)

Ten notable quotes:

“Man fears time, but time fears the pyramids.” – Arab Proverb

“It is the nature of the human being to seek to be understood, to find a place to fit in, to find a place where he belongs. The pyramids are a reminder that people have always strived to leave a mark, to be remembered.” – Unknown.

“The pyramids seem to say to us: Remember that everything you do in life will fade; but the things you build with true passion and for the benefit of all, those will remain.” – Unknown.

“Without question, the greatest archaeological achievement of mankind, the Great Pyramid of Giza has inspired generations to wonder at its mystery and marvel at its engineering.” – Zahi Hawass.

“In the simplicity of its form, the pyramid embodies the power and will of ancient Egypt, standing defiant against the wind and time itself.” – Unknown.

“The construction of the pyramids is a reminder of what a unified society can achieve when its resources and efforts are focused on a single goal.” – Mark Lehner.

“To stand at the foot of the pyramids is to stand in the presence of timeless ambition and human tenacity.” – Unknown.

“The pyramids were not built in isolation; they were the product of a thriving civilization with a deep understanding of mathematics, astronomy, and social organization.” – I.E.S. Edwards.

“The Great Pyramid is not just a marvel of architecture but a symbol of the enduring human desire for legacy and immortality.” – Unknown.

“They are silent yet eloquent witnesses to the grandeur and power of the ancient world, holding secrets only the past can tell.” – Unknown.

Table:

| Approximate Year (BCE) | Pyramid | Pharaoh | Engineering & Architecture | Astronomy | Art & Decoration |

| c. 2780 | Step Pyramid of Djoser | Djoser | – First true pyramid <br> – Stacked mastaba design <br> – Use of dressed stone | – Possibly aligned with cardinal directions | – Early reliefs and decorative elements |

| c. 2600 | Bent Pyramid | Sneferu | – Experimentation with smooth sides <br> – Change in angle during construction | – More precise alignment with cardinal directions | – Limited internal decoration |

| c. 2590 | Red Pyramid | Sneferu | – First successful smooth-sided pyramid <br> – Improved construction techniques | – Accurate alignment with cardinal directions | – Simple internal chambers |

| c. 2580 | Great Pyramid of Giza | Khufu (Cheops) | – Largest Egyptian pyramid <br> – Precisely cut and fitted stones <br> – Internal chambers and passages | – Aligned with True North with remarkable accuracy | – Remains of casing stones show fine craftsmanship |

| c. 2570 | Pyramid of Khafre | Khafre (Chephren) | – Second-largest pyramid at Giza <br> – Valley temple and causeway | – Aligned with cardinal directions | – Statues and reliefs in the valley temple |

| c. 2510 | Pyramid of Menkaure | Menkaure (Mykerinus) | – Smaller scale but still precise construction | – Aligned with cardinal directions | – Granite casing on the lower levels |

| c. 2490 – 2323 | Pyramids of 5th Dynasty Pharaohs (Userkaf, Sahure, Neferirkare, etc.) | Various | – Smaller pyramids <br> – More complex internal structures | – Generally aligned with cardinal directions | – Reliefs and inscriptions become more elaborate |

| c. 2345 | Pyramid of Unas | Unas | – Contains the earliest known Pyramid Texts | – Alignment with cardinal directions | – Extensive Pyramid Texts inscribed on the walls of the burial chamber |

| c. 2323 – 2150 | Pyramids of 6th Dynasty Pharaohs (Teti, Pepi I, Merenre, Pepi II) | Various | – Further development of Pyramid Texts | – Continued alignment with cardinal directions | – Elaborate internal decorations and Pyramid Texts |

| c. 2040 – 1640 | Various smaller pyramids | Middle Kingdom Pharaohs | – Decline in size and precision | – Less precise alignment | – Simpler internal decorations |

Export to Sheets

YouTube Video

Decoding the Great Pyramid | Full Documentary | NOVA | PBS

Full tour inside the Great Pyramid of Giza | Pyramid of Cheops …

Closest Look Ever at How Pyramids Were Built

History:

The Egyptian pyramids are some of the most iconic structures in human history. They serve as monumental tombs for the pharaohs and are a testament to ancient Egypt’s architectural, engineering, and organizational skills. Built over several centuries, they reflect Egypt’s evolution in political power, religious beliefs, and societal development.

Early Development of Pyramids

The earliest precursors to pyramids were simple burial mounds called mastabas, flat-roofed rectangular structures built over underground burial chambers. These mastabas, constructed during Egypt’s early dynastic period (c. 3100–2686 BCE), were used by Egypt’s elite and royal families as burial sites.

The transition from mastabas to pyramids began with Pharaoh Djoser of the Third Dynasty (c. 2670 BCE), who commissioned the construction of a more monumental tomb in Saqqara near Memphis. His architect, Imhotep, designed the Step Pyramid of Djoser, the first large stone structure in history. This pyramid consisted of six mastaba-like layers stacked atop each other, forming a “step” structure. It marked a revolutionary change in architecture and laid the groundwork for the later development of true pyramids.

The Great Pyramids of Giza

The construction of true pyramids peaked during the Fourth Dynasty (c. 2613–2494 BCE), with the famous pyramids of Giza, which remain among the largest and most well-known pyramids today.

- The Pyramid of Khufu (Great Pyramid): Built around 2580–2560 BCE, the Great Pyramid is the largest pyramid ever constructed and was originally about 146 meters (480 feet) tall. It was built for Pharaoh Khufu (also known as Cheops) and is composed of approximately 2.3 million limestone blocks, each weighing around 2.5 tons on average. This pyramid is a marvel of engineering and one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the only one still largely intact. It also houses intricate chambers and passages, with the “King’s Chamber” at its center.

- The Pyramid of Khafre: The second-largest pyramid at Giza was built by Khufu’s son, Pharaoh Khafre, around 2570 BCE. This pyramid appears slightly taller than the Great Pyramid due to its construction on higher ground but is somewhat smaller. Khafre’s pyramid is unique for having a large portion of its original smooth casing stones still intact at the top, showing how the pyramids once looked. This pyramid complex includes the Great Great Sphinx, a massive statue with a human’s head and a lion’s body, which is believed to represent Khafre himself.

- The Pyramid of Menkaure: The smallest of the three pyramids, this was built by Khufu’s grandson, Pharaoh Menkaure, around 2510 BCE. Though smaller, Menkaure’s pyramid is notable for its complex design and the finer materials used in parts of its construction. It was initially faced with granite, a material more challenging to work with than limestone, showcasing Menkaure’s dedication to crafting an impressive final resting place.

Purpose and Religious Beliefs

The pyramids served as tombs for pharaohs and their consorts and were designed to ensure the pharaoh’s safe passage to the afterlife. Ancient Egyptians believed in a complex afterlife, where the soul, or ka, would need provisions, protection, and guidance to reach the next world. The pyramid structure symbolized the primordial mound from which life was believed to have originated and was intended to facilitate the pharaoh’s journey to the afterlife, ensuring his transformation into a divine being.

Inside the pyramids, various burial chambers, false passages, and traps were designed to protect the king’s remains and treasures from grave robbers. The walls of later pyramids were often inscribed with religious texts, known as the Pyramid Texts, which contained spells and rituals to help the pharaoh in the afterlife.

Decline of Pyramid Building

By the time of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties (c. 2494–2181 BCE), pyramid construction began to decline. The pyramids became smaller, and their quality decreased, partly due to economic constraints and possibly a shift in religious beliefs. Instead, the emphasis turned to elaborate temple complexes and funerary texts inscribed on the tomb walls.

During the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BCE), pharaohs continued to build pyramids, but these were smaller and often constructed with mudbrick cores, which did not last as well as stone. The political instability of later dynasties and the shift of the capital away from the Giza area contributed to the decline of pyramid-building.

Legacy and Influence

The Egyptian pyramids, especially those at Giza, have fascinated people for thousands of years. They have become symbols of Egypt’s rich history and enduring achievements. Ancient Greek historians, such as Herodotus, wrote about the pyramids, often with exaggerated accounts of slave labor and mystical origins. Modern archaeology has revealed that the pyramids were built by a highly organized labor force, likely composed of skilled laborers and seasonal workers rather than slaves.

Today, the pyramids are a testament to ancient Egypt’s advancements in mathematics, engineering, and astronomy. They continue to attract researchers and tourists from around the world, offering insights into the technological prowess and spiritual beliefs of an ancient civilization that continues to captivate the modern imagination.

Egyptian Pyramids Details and Pictures

Egyptian Pyramids Early Development of Pyramids

The early development of the Egyptian pyramids is a testament to ancient Egypt’s innovative spirit and evolving engineering techniques. The architectural journey that led to the creation of the iconic pyramids began with simpler forms and gradually evolved into the grand structures we recognize today.

Mastabas – The Foundations of Pyramid Design

The earliest royal tombs in ancient Egypt were mastabas, which date back to the early dynastic period (c. 3100–2686 BCE). These flat-roofed, rectangular structures made of mudbrick or stone had sloping sides and served as burial chambers for kings and high officials, laying the groundwork for more complex burial structures.

The Step Pyramid of Djoser

(Wiki Image By Charlesjsharp at English Wikipedia – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25275228)

The first major innovation came with constructing the Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara around 2670 BCE during the Third Dynasty. Designed by the architect Imhotep, this structure represented a significant advancement in pyramid design. It was a series of six mastabas stacked on one another, creating a stepped appearance. This was the first large-scale stone structure in human history, marking the beginning of monumental pyramid construction.

The Bent Pyramid at Dahshur

The transition from step pyramids to true smooth-sided pyramids began with the Bent Pyramid, built for Pharaoh Sneferu (c. 2600 BCE) in Dahshur. This pyramid started with steep sides but changed to a gentler slope midway through construction, resulting in its unique “bent” appearance. Scholars believe this adjustment was made to prevent structural collapse, showcasing an early understanding of architectural challenges.

The Red Pyramid – The First True Pyramid

(Wik Imagei By Sturm58 at the English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25275244)

Sneferu’s final attempt at pyramid building led to the creation of the Red Pyramid, also at Dahshur. It was the first successful true pyramid, with smooth, straight sides, completed around 2600 BCE. The Red Pyramid demonstrated the culmination of Sneferu’s engineering experiments and set the stage for future pyramid construction.

The Great Pyramids of Giza

The Fourth Dynasty marked the apex of pyramid construction with the Great Pyramid of Giza, built for Pharaoh Khufu (c. 2560 BCE). This massive structure stood as the tallest man-made building in the world for over 3,800 years. Khufu’s pyramid was followed by the construction of two other significant pyramids: Khafre’s Pyramid, which includes the iconic Great Sphinx, and Menkaure’s Pyramid.

Key Characteristics of Early Pyramids:

- Material Evolution: From mudbrick to limestone and granite as building materials.

- Architectural Innovations: The gradual shift from stepped to smooth-sided designs to improve structural stability and achieve greater heights.

- Symbolic Significance: Pyramids were not just tombs but symbols of royal power, religious belief in the afterlife, and the connection between the pharaoh and the gods, particularly Ra, the sun god.

Legacy:

The development of the pyramids represented significant advancements in engineering, mathematics, and labor organization. These early structures were a precursor to the grandeur of the later pyramids and remain an enduring symbol of ancient Egyptian civilization and its ingenuity. The evolution from mastabas to the magnificent pyramids of Giza marks a pivotal point in the history of architecture and continues to captivate historians and visitors alike.

Egyptian Pyramids The Great Pyramids of Giza

Egyptian Pyramid of Khufu (Great Pyramid)

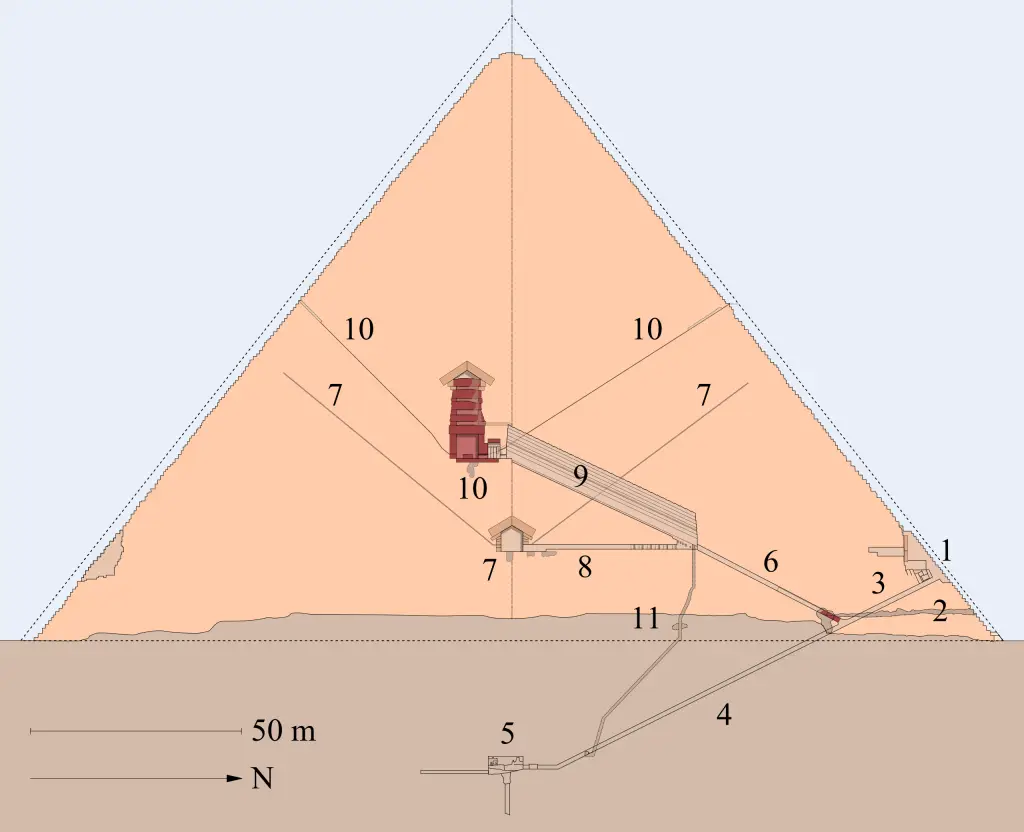

Diagram of the interior structures of the Great Pyramid. The inner line indicates the pyramid’s present profile, and the outer line indicates the original profile.

(Wiki Image By Flanker, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41041394)

The Great Pyramid of Khufu, also known as the Pyramid of Cheops, is the largest and most famous pyramid on the Giza Plateau. It was built during the Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom, around 2560 BCE, for Pharaoh Khufu (also known as Cheops in Greek). This pyramid is one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World and is the only one that remains largely intact today.

Key Facts about the Great Pyramid of Khufu:

- Construction Period: Historians estimate that the Great Pyramid’s construction took about 20 years, starting around 2580 BCE.

- Architectural Design: The pyramid’s original height was approximately 146.6 meters (481 feet), but due to the loss of the outer casing stones, it now stands at 138.8 meters (455 feet). It was the tallest man-made structure in the world for over 3,800 years until the construction of the Lincoln Cathedral in England in 1311.

- Materials Used: The pyramid was constructed using around 2.3 million blocks of limestone and granite, with the average block weighing between 2.5 and 15 tons. The granite stones used in the King’s Chamber were transported from Aswan, over 800 kilometers away.

- Labor Force: Contrary to the long-held belief that slaves built the Great Pyramid, modern archaeological evidence suggests that it was constructed by a skilled workforce of thousands of laborers living near workers’ villages. These workers were likely well-fed and organized in rotating labor teams.

- Interior Structure: The pyramid contains a series of chambers and passages. The King’s Chamber, made of granite, is located at the heart of the pyramid and includes the sarcophagus that once held Khufu’s body. Above it are five relieving chambers designed to reduce pressure and prevent the chamber from collapsing. The Grand Gallery is a large corridor that leads to the King’s Chamber, showcasing the ingenuity of ancient engineers.

- Casing Stones: The Great Pyramid was originally covered with highly polished Tura limestone casing stones that would have made the structure shine brilliantly under the sun. Most of these stones have since been removed or eroded, revealing the underlying core structure.

Purpose and Symbolism:

The Great Pyramid was built as a tomb for Pharaoh Khufu, symbolizing the king’s journey to the afterlife. It was aligned with remarkable precision to the cardinal points (north, south, east, and west), reflecting the ancient Egyptians’ advanced understanding of astronomy and their belief in the pyramid’s role in guiding the pharaoh’s soul to the afterlife. The shape of the pyramid itself was symbolic, representing the sun’s rays and serving as a means for the pharaoh’s ascent to join Ra, the sun god.

Construction Techniques:

Historians and archaeologists debate and marvel at the exact methods used to build the Great Pyramid. Various theories include using straight or zigzagging ramps, spiral ramps constructed around the exterior, or levers and pulleys. Despite many theories, the specific methods remain a testament to the ingenuity of ancient Egyptian engineering and logistics.

Legacy and Significance:

The Great Pyramid of Khufu is a testament to ancient Egypt’s ambition, organization, and technological prowess. Its construction showcases the sophistication of ancient engineering and continues to inspire awe and curiosity. As a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the only surviving wonder of the ancient world, the Great Pyramid continues to be a powerful symbol of human achievement and ancient Egyptian civilization.

Egyptian Pyramid of Khafre

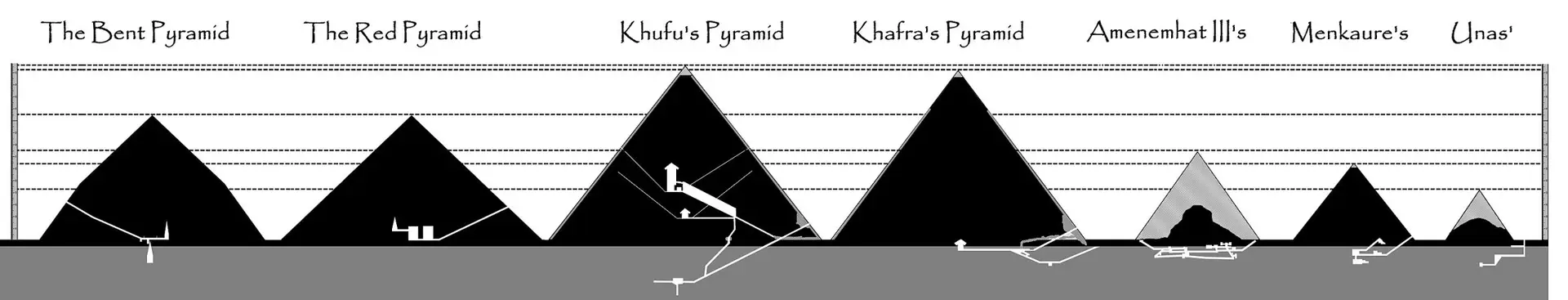

Famous pyramids (cut-through with internal labyrinth layout).

(Wiki Image By Caroline Lévesque – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=116521250)

The Pyramid of Khafre, also known as the Pyramid of Chephren, is the second-largest of the three main pyramids on the Giza Plateau and is located next to the Great Pyramid of Khufu. It was constructed during the Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom, around 2520–2494 BCE, for Pharaoh Khafre, Khufu’s son. Although slightly smaller than the Great Pyramid, it appears taller due to its construction on higher ground and steeper angle.

Key Features of the Pyramid of Khafre:

- Height: Originally, the Pyramid of Khafre stood at 143.5 meters (471 feet), but today, it measures about 136.4 meters (448 feet) due to the loss of some of its outer stones.

- Casing Stones: Unlike the Great Pyramid, the Pyramid of Khafre still retains some of its original Tura limestone casing stones at the apex, giving a glimpse into how the pyramids initially looked with smooth, polished exteriors.

- Architectural Design: The pyramid’s base length is 215.5 meters (706 feet) and was built using large limestone blocks. Its construction includes an inner chamber, various corridors, and a burial chamber that housed the pharaoh’s sarcophagus.

- Complex Structure: The pyramid is part of a larger mortuary complex that includes a mortuary temple, a causeway, and the Valley Temple. These structures were integral to the pharaoh’s mortuary rituals and were connected to facilitate the journey of Khafre’s spirit to the afterlife.

The Great Great Sphinx of Giza:

One of the most notable aspects of Khafre’s complex is the Great Sphinx, which is in front of his pyramid. The Great Sphinx, with the body of a lion and the head of a human, is believed by many scholars to bear the likeness of Pharaoh Khafre and serves as a guardian of the Giza Plateau. Carved from the natural bedrock, the Great Sphinx is one of the world’s largest and oldest monolithic statues, symbolizing strength and wisdom.

Interior Layout:

The burial chamber of the Pyramid of Khafre is simpler than that of the Great Pyramid of Khufu. It is located underground and accessed through a descending passage. Unlike the Grand Gallery in the Great Pyramid, Khafre’s pyramid has a less complex interior but maintains the precision in construction that the ancient Egyptians were renowned for. The inner core was built from local limestone, while the outer casing, now mostly gone, was made from higher-quality stone.

Construction Techniques:

Like the Great Pyramid, the exact methods used to construct the Pyramid of Khafre are still debated. Ancient builders likely employed similar techniques involving ramps, sleds, and manual labor. Modern archaeologists believe the labor force comprised skilled workers rather than slaves, with evidence showing that laborers lived in nearby workers’ villages and were provided with food and accommodations.

Symbolism and Purpose:

The Pyramid of Khafre served as a testament to the pharaoh’s divine power and his role as a bridge between the gods and the people. It was part of the Egyptian belief in the afterlife, ensuring that Khafre’s spirit could ascend to the heavens and join the sun god Ra. The construction of such monumental structures reinforced the idea of the pharaoh’s eternal presence and the importance of maintaining cosmic order, or ma’at.

Legacy:

The Pyramid of Khafre, its surrounding structures, and the Great Sphinx remain among the world’s most remarkable and studied ancient sites. They continue to symbolize ancient Egypt’s might, ingenuity, and spiritual beliefs. As part of the Giza Plateau, they contribute to the area’s status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, drawing millions of visitors each year who marvel at the architectural achievements of one of history’s most influential civilizations.

Egyptian Pyramid of Menkaure

The Pyramid of Menkaure is the smallest of the three main pyramids on the Giza Plateau and was built for Pharaoh Menkaure (Mykerinos in Greek), who ruled during the Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom, around 2490–2472 BCE. Despite being smaller than the Pyramids of Khufu and Khafre, the Pyramid of Menkaure is significant for its unique construction elements and the intricacies of its mortuary complex.

Key Features of the Pyramid of Menkaure:

- Height: Originally, the Pyramid of Menkaure stood at approximately 65 meters (213 feet), but due to the erosion and loss of outer casing stones, it now measures about 61 meters (204 feet).

- Base: The pyramid has a base length of 102.2 meters (335 feet).

- Materials: Unlike the larger pyramids of Khufu and Khafre, primarily constructed with limestone, the Pyramid of Menkaure used significant amounts of granite in its lower courses and inner chambers. The granite was transported from Aswan, about 800 kilometers, to the south, showcasing the labor and resources dedicated to this structure.

- Casing Stones: Some remnants of the original granite casing stones can still be seen at the lower parts of the pyramid. These stones would have given the pyramid a distinctive appearance when it was first constructed.

Architectural Design:

The Pyramid of Menkaure is notable for its more elaborate and detailed mortuary temple than the earlier pyramids. The mortuary temple was constructed using large blocks of limestone and granite and features intricate designs and inscriptions. It connected to the Valley Temple via a causeway. While the pyramid’s interior is more spartan than Khufu’s, it still includes descending passages, chambers, and an unfinished burial chamber.

Mortuary and Valley Temples:

Menkaure himself partially completed the Mortuary Temple associated with the Pyramid of Menkaure, which was later finished by his successor, likely Shepseskaf. The Valley Temple is believed to have played a significant role in the funeral rites and preparation of the pharaoh’s body before it was placed in the pyramid. Excavations have revealed a wealth of statues and artifacts, including a remarkable statue of Menkaure and his queen, now housed in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Symbolism and Purpose:

Like the other pyramids at Giza, the Pyramid of Menkaure was constructed as a royal tomb and symbolized the pharaoh’s journey to the afterlife. The use of granite in its construction may have emphasized Menkaure’s desire for permanence and durability, reinforcing his divine status and ensuring his eternal life. The choice of high-quality materials and detailed design in the mortuary temple reflects the importance placed on the afterlife and the pharaoh’s role as an intermediary between the gods and the people.

Construction and Labor:

Evidence suggests that the construction of the Pyramid of Menkaure, like its predecessors, was carried out by a skilled workforce rather than slaves. Workers were organized into teams and supported by a complex infrastructure that provided food, housing, and medical care. Using granite, a much harder material to work with than limestone, indicates advanced engineering skills and significant labor investment.

Legacy:

The Pyramid of Menkaure may be smaller in scale than the Pyramids of Khufu and Khafre, but it holds great historical and cultural value. Its unique use of granite and the elaborate mortuary temple highlight the evolution of pyramid construction techniques and the religious significance attributed to these monumental structures. The pyramid continues to draw interest from historians, archaeologists, and visitors who come to explore the legacy of ancient Egypt’s architectural and spiritual achievements.

As part of the Giza Pyramid Complex, the Pyramid of Menkaure contributes to the plateau’s collective identity as a symbol of ancient Egyptian power, religion, and innovation.

Egyptian Pyramids’ Purpose and Religious Beliefs

Here are some images featuring the Egyptian Pyramids and their connection to religious beliefs:

The Pyramids as Tombs:

- The majestic silhouette of the pyramids against the desert sunset symbolizes their enduring presence and the pharaohs’ passage into the afterlife.

pyramids of Giza at sunset

- The intricate network of passages and chambers within a pyramid leads to the burial chamber where the pharaoh’s sarcophagus rested.

interior of a pyramid with passages and chambers

Religious Symbolism:

- The pyramid’s shape resembles a giant staircase reaching towards the heavens, representing the pharaoh’s ascent to the sun god Ra.

pyramid with a focus on its shape

- Hieroglyphs and paintings on the pyramid walls depict scenes from Egyptian mythology and rituals related to death and rebirth.

Hieroglyphs and paintings on a pyramid wall

- The pyramids’ precise alignment with cardinal directions and stars suggests their connection to celestial observations and the Egyptians’ belief in cosmic order.

pyramids aligned with cardinal directions

Mortuary Temples and Rituals:

- The elaborate mortuary temple complex near the pyramids, where priests performed rituals and offerings to ensure the pharaoh’s successful afterlife journey.

mortuary temple complex near a pyramid

- The Valley Temple, located at the edge of the desert, where the pharaoh’s body was mummified and prepared for burial.

Valley Temple near a pyramid

The Pyramids’ Enduring Legacy:

- The pyramids stand as a testament to the ancient Egyptians’ ingenuity, skill, and dedication. They reflect their advanced engineering capabilities and their profound belief in the afterlife.

pyramids from a distance, showcasing their size and scale

These images offer a glimpse into the fascinating world of the Egyptian pyramids, where architecture, religion, and belief intertwine to create these iconic monuments that continue to captivate us today.

Egyptian Pyramids Decline of Pyramid Building

Map of the Giza Pyramid complex

(Wiki Image By MesserWoland, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1030413)

The decline of pyramid building in ancient Egypt was a gradual process influenced by economic, political, and cultural factors. While the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BCE) is considered the “Age of the Pyramids” due to the construction of monumental structures such as the Great Pyramid of Khufu, subsequent periods saw changes that led to the eventual cessation of building large-scale pyramids.

Economic Constraints

One major reason for the decline in pyramid building was the significant economic strain these massive projects placed on the state. Pyramid construction required immense resources, including manpower, materials, and logistical coordination. The centralized state, which had been strong during the Old Kingdom, weakened over time due to financial challenges.

- Cost of Labor and Resources: The labor force needed for pyramid construction included thousands of skilled workers who needed to be fed, housed, and managed. Quarrying and transporting stone, particularly high-quality limestone and granite, became increasingly difficult and expensive.

- Shift in Resources: By the end of the Old Kingdom, economic resources became strained, making it difficult to justify the construction of monumental pyramids. This economic decline contributed to a decrease in state-sponsored construction projects.

Political Fragmentation

The stability of the Egyptian state was essential for large-scale pyramid projects. The decline in pyramid construction coincided with periods of political fragmentation and instability.

- First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BCE): Following the collapse of the Old Kingdom, Egypt entered a period of disunity known as the First Intermediate Period. The central government weakened, and regional governors (nomarchs) gained more power, leading to political fragmentation. Pyramid construction practice diminished without a strong centralized government coordinating and financing it.

- Changes in Ruling Dynasties: The subsequent Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BCE) saw a brief resurgence in pyramid building. Still, the scale and grandeur of the pyramids were significantly reduced compared to those of the Old Kingdom. Pyramids from the Middle Kingdom, such as those at Lisht and Dahshur, were often constructed using mudbrick cores instead of solid stone, making them less durable and more prone to decay over time.

Shifting Religious Beliefs

Changes in religious beliefs also contributed to the decline of pyramid construction. While the Old Kingdom emphasized the pyramid as a key element in the pharaoh’s journey to the afterlife, later periods saw shifts in funerary practices and religious symbolism.

- Valley of the Kings: By the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE), the practice of pyramid building was largely replaced by the construction of rock-cut tombs in the Valley of the Kings near Thebes. These tombs were less conspicuous and less vulnerable to tomb robbers. The emphasis shifted from constructing monumental pyramids to creating hidden, secure tombs with elaborate wall paintings and funerary texts designed to aid the pharaoh’s passage to the afterlife.

- Increased Importance of the Gods: The religious landscape shifted to emphasize gods such as Amun and Osiris, with temples and mortuary complexes dedicated to these deities receiving more resources and attention than royal tombs. The pharaoh’s tomb became one part of a larger religious complex rather than the central focus of a ruler’s legacy.

Security Concerns and Tomb Robbery

The pyramids’ visibility and grandeur made them prime targets for tomb robbers. Despite efforts to include false chambers and complex passageways to protect the pharaoh’s treasures, most pyramids were looted within a few generations of their construction.

- Shift to Hidden Tombs: Later dynasties opted for more discreet burial sites to combat looting. The hidden tombs of the Valley of the Kings were more secure than pyramids and allowed for better protection of the pharaoh’s possessions and mummified bodies.

- Reduced Significance of Tomb Contents: Over time, the focus on building massive structures for tombs lessened, and instead, more emphasis was placed on protecting the body and grave goods through secrecy.

Architectural and Material Limitations

The architectural techniques used in pyramid construction evolved but with certain limitations.

- Inferior Building Materials: During the Middle Kingdom, pyramids were often constructed with mudbrick cores covered with limestone casing. Unlike the solid stone blocks used in Old Kingdom pyramids, these materials were less durable and eroded more quickly, reducing the overall longevity and splendor of the structures.

- Complexity of Rock-Cut Tombs: The development of rock-cut tombs in the New Kingdom allowed for intricate and extensive funerary decorations without needing large, external stone structures. This shift also reflected changing architectural preferences that favored concealed tombs with richly painted chambers.

Summary

The decline of pyramid building in ancient Egypt resulted from economic pressures, political fragmentation, changing religious beliefs, security concerns, and material limitations. As the pharaohs’ centralized power waned and resources were redistributed, the focus shifted from building grand pyramids to creating hidden, secure tombs that could better protect the pharaoh’s journey to the afterlife. This shift marked an evolution in the practical and spiritual approaches to burial practices, reflecting ancient Egyptian society’s changing priorities and realities.

Egyptian Pyramids Legacy and Influence

Sure, here are some images featuring the legacy and influence of the Egyptian Pyramids:

The enduring legacy of the pyramids:

-

Great Pyramids of Giza at sunset, casting long shadows across the desert landscape.

-

tourists marveling at the intricate hieroglyphics and carvings on the walls of a pyramid.

-

modern museum exhibit showcasing artifacts recovered from ancient Egyptian pyramids.

The pyramids as a source of inspiration for art and literature:

-

painting by a renowned artist depicting the pyramids in a dreamlike or symbolic style.

-

book cover featuring a pyramid as a central element in a story about ancient Egypt.

-

movie scene showcasing the pyramids as a backdrop for an adventure or historical drama.

The pyramids as a symbol of human ingenuity and ambition:

-

closeup view of the perfectly cut and fitted stones of a pyramid, highlighting the advanced engineering skills of the ancient Egyptians.

The Egyptian pyramids are a testament to ancient civilization’s power, ingenuity, and enduring legacy. They continue to inspire awe and wonder in people worldwide and remind us of the human capacity for great achievement.

Karnak Temple History

Photograph of the temple complex taken in 1914, Cornell University Library

(Wiki Image By Cornell University Library – originally posted to Flickr as Temple Complex at Karnak, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7252716)

Ten notable quotes:

“Karnak Temple is not just a building, it is an entire city of temples, reflecting the grandeur and spiritual devotion of ancient Thebes.” – Unknown.

“Walking through Karnak is like stepping into a colossal open-air museum, where every column and every statue tells the story of a powerful civilization.” – Unknown.

“The Temple of Karnak stands as a testament to the collective effort and vision of generations, showcasing the dedication of Pharaohs over a span of 2,000 years.” – Zahi Hawass.

“Karnak is an awe-inspiring place, a spiritual and architectural masterpiece that reveals the peak of ancient Egyptian religious devotion.” – Unknown.

“The grandeur of Karnak is unparalleled, a place where history and myth intertwine in every hall and sanctuary.” – Unknown.

“Karnak Temple is a mirror into the past, showcasing the heights of human ingenuity and the depth of devotion to the divine.” – Unknown.

“To explore Karnak is to witness the evolution of ancient Egyptian art and religious thought, each Pharaoh adding his touch to its magnificence.” – Mark Lehner.

“Karnak is the embodiment of the Egyptians’ architectural and spiritual ambition, with its towering pylons, intricately carved hieroglyphs, and sacred lakes.” – Unknown.

“The Temple of Karnak serves as a grand chronicle of Theban power and religious practices, demonstrating how deeply intertwined their gods were with daily life.” – I.E.S. Edwards.

“No other temple complex in the world has the overwhelming presence and sheer scale of Karnak; it is both a place of worship and a statement of imperial might.” – Unknown.

Table:

| Approximate Year (BCE) | Pharaoh/Period | Engineering & Architecture | Astronomy | Art & Decoration |

| c. 2055-1650 (Middle Kingdom) | Various | – Early structures were built, including the core of the Temple of Amun-Re. <br> – Use of mudbrick and some stone. | – Alignment of early structures with the sun’s path. | – Limited surviving decoration from this period. |

| c. 1570-1070 (New Kingdom) | Major Expansion and Development | |||

| c. 1504-1492 | Hatshepsut | – Red Chapel (Chapelle Rouge), innovative use of red quartzite. <br> – Obelisks erected (one still standing). | – Obelisks aligned with the sun’s solstices. | – Reliefs depicting Hatshepsut’s divine birth and accomplishments. |

| c. 1479-1425 | Thutmose III | – Festival Hall (Akh-menu), with intricate columns and reliefs. <br> – Additions to the Temple of Amun-Re. | – Possible astronomical alignments in the Festival Hall. | – Reliefs depicting Thutmose III’s military victories and offerings to the gods. |

| c. 1391-1353 | Amenhotep III | – Luxor Temple, connected to Karnak by a processional avenue. <br> – Massive statues and pylons. | – Alignment of Luxor Temple with the Nile’s east-west axis. | – Colossal statues of Amenhotep III and scenes of religious rituals. |

| c. 1353-1336 | Akhenaten | – Temples dedicated to the Aten (sun disk), his new monotheistic god. (Later dismantled) | – Emphasis on open-air structures to allow sunlight. | – Unique artistic style depicting Akhenaten and his family in an elongated, stylized manner. |

| c. 1336-1327 | Tutankhamun | – Restoration of traditional temples and dismantling of Aten temples. | – Return to traditional temple alignments. | – Restoration of traditional religious imagery. |

| c. 1279-1213 | Ramesses II | – Great Hypostyle Hall, a massive hall with 134 columns. <br> – Pylons and courtyards. | – Possible astronomical alignments in the Hypostyle Hall. | – Reliefs depicting Ramesses II’s battles and his role as a divine ruler. |

| c. 664-30 (Late Period and Ptolemaic Period) | Various | – Smaller temples and additions. <br> – Kiosk of Taharqa, a unique structure with intricate columns. | – Continued attention to solar and astronomical alignments. | – Variety of artistic styles reflecting the changing influences of different rulers. |

| 30 BC – 4th Century AD (Roman and Christian Era) | – Some Roman additions and modifications. <br> – Conversion of some temples to Christian churches. | – | – Christian artwork and modifications to existing structures. |

Export to Sheets

YouTube Video

Virtual Egypt: The Biggest Egyptian Temple – Karnak

Egypt:The Temple of Karnak | The Lost Civilizations

History:

The Karnak Temple Complex, located in modern-day Luxor (ancient Thebes) in Upper Egypt, is one of the world’s most impressive and expansive ancient religious sites. It spans over 200 acres and includes a vast network of temples, chapels, obelisks, and other monumental structures primarily dedicated to the god Amun-Ra, the chief deity of Thebes.

Early Beginnings and Evolution

Construction at Karnak began in the Middle Kingdom, around 2000 BCE, and continued over many centuries, reaching its peak during the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE). The site became the god Amun’s primary religious center, which grew increasingly crucial during the New Kingdom as Thebes became Egypt’s capital. Pharaohs from the 18th, 19th, and 20th dynasties, such as Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Seti I, and Ramesses II, expanded and modified the complex to showcase their devotion to Amun and to solidify their own legitimacy and divine status.

Karnak’s expansion was primarily a result of each pharaoh attempting to honor Amun and leave their legacy. Over generations, the site became a sprawling complex, with pharaohs adding new temples, halls, and obelisks. This continuous construction created a unique architectural evolution, making Karnak a living document of Egyptian religious, architectural, and artistic developments.

Layout and Major Sections of Karnak

Karnak consists of four main precincts, the largest and most significant of which is dedicated to Amun. The three other precincts are devoted to the goddess Mut (Amun’s consort), the god Montu (a war deity), and an enclosure associated with the deified rulers.

- The Precinct of Amun-Ra: This is the most extensive and most elaborate section of Karnak, dominated by the Great Hypostyle Hall, a massive structure covering around 54,000 square feet with 134 gigantic sandstone columns. Built primarily by Seti I and Ramesses II, the hall remains one of ancient Egypt’s most awe-inspiring architectural feats. It also includes the Sacred Lake, which was used for ritual purification, and several obelisks, the tallest of which was erected by Hatshepsut.

- Temple of Mut: Located south of the main complex, this precinct was dedicated to Mut, Amun’s wife, surrounded by hundreds of statues of the lion-headed goddess Sekhmet associated with Mut. This temple was an essential part of the Theban triad, which included Amun, Mut, and their son, Khonsu, the moon god.

- Temple of Khonsu: A smaller temple dedicated to Khonsu, Amun and Mut’s son, lies within the Amun precinct. It is relatively well-preserved and features fine reliefs and inscriptions that depict religious rituals associated with this god.

- Festival Halls and Chapels: Pharaohs, notably Thutmose III, added festival halls, such as the Akh-Menu or Festival Hall of Thutmose III, a unique structure featuring botanical and animal reliefs, possibly inspired by his military campaigns in Syria.

Religious and Cultural Significance

Karnak was not just a place of worship but also a site for political expression and the affirmation of the pharaoh’s power. As the center of Amun’s worship, the temple complex was integral to state rituals, especially during the annual Opet Festival. During this festival, the statue of Amun was carried from Karnak to Luxor Temple in a grand procession along the Nile, symbolizing the pharaoh’s divine relationship with Amun and renewing the king’s power.

The temple symbolized the Egyptian worldview and belief system, connecting the pharaoh and the gods in a cosmic order. Each pharaoh’s additions to Karnak demonstrated their devotion and desire to be remembered as a patron of the gods and protector of Egypt.

Later History and Decline

With the decline of the New Kingdom, Karnak’s significance diminished, though it continued to be used and modified during later periods, including the Ptolemaic and Roman eras. However, as Egypt transitioned to Christianity and later Islam, the complex eventually fell into disuse, and its structures were buried under centuries of sand and silt.

In the 19th century, European archaeologists and Egyptologists began excavating Karnak, revealing its monumental structures and inscriptions. Today, ongoing archaeological efforts continue to uncover new insights into the history of Karnak, with conservation efforts in place to protect its ancient legacy.

Legacy and Modern-Day Significance

Karnak Temple Complex remains one of Egypt’s most visited and studied sites. It is an extraordinary testament to ancient Egypt’s religious, architectural, and artistic achievements. The grandeur of Karnak, notably the Great Hypostyle Hall, continues to captivate visitors and scholars, offering a unique glimpse into the religious life and worldviews of ancient Egyptians. Its significance as a spiritual and cultural center has made it an enduring symbol of Egypt’s ancient heritage, drawing millions of tourists annually and providing invaluable insights into Egypt’s storied past.

Karnak Temple Details and Pictures

The Precinct of Amun-Re as seen from the Sacred Lake

(Wiki Image By Taranis-iuppiter – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=29910389)Karnak Temple’s Early Beginnings and Evolution

Karnak Temple’s Early Beginnings and Evolution

You’re interested in a concise overview of Karnak Temple’s early development! It’s fascinating to trace how this monumental complex grew from modest beginnings into a sprawling religious center. Here’s a table summarizing its key evolutionary stages:

| Period | Pharaohs & Dynasties | Key Developments | Picture Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Middle Kingdom | – Senusret I (12th Dynasty)<br> – Other Middle Kingdom rulers | – Modest beginnings: Relatively small temple dedicated to Amun, a local Theban deity. <br> – White Chapel: Construction of a white limestone chapel by Senusret I. <br> – Middle Kingdom Court: Establishment of a basic court, forming the core for later expansion. |

White Chapel of Senusret I, a surviving example of early Karnak.

|

| New Kingdom | – Hatshepsut (18th Dynasty)<br> – Thutmose III (18th Dynasty)<br> – Amenhotep III (18th Dynasty)<br> – Seti I (19th Dynasty)<br> – Ramses II (19th Dynasty) | – Theban Ascendancy: Karnak’s importance grows as Thebes becomes Egypt’s capital. <br> – Monumental Additions: Obelisks, pylons, and grand halls are added, dramatically increasing the temple’s size. <br> – Great Hypostyle Hall: Construction begins under Seti I and is continued by Ramses II. | <br>

obelisk of Hatshepsut, showcasing the grandeur of New Kingdom additions.

|

| Late Period | – Kushite Pharaohs (25th Dynasty)<br> – Ptolemies (305-30 BCE) | – Reduced Power, Continued Building: Thebes’ decline leads to less grand construction, but the temple continues to evolve. <br> – Kushite Revival: Restoration and expansion under Kushite pharaohs. <br> – Ptolemaic Influence: New temples and modifications incorporating Greek elements. |

structure from the Ptolemaic period at Karnak, showing the influence of Greek architecture.

|

Key Takeaways

- Gradual Growth: Karnak Temple evolved over centuries, reflecting changes in religious practices, political power, and architectural styles.

- Middle Kingdom Origins: It started as a modest temple to Amun and gradually expanded with Thebes’s growing importance.

- New Kingdom Grandeur: The New Kingdom saw the most significant expansion, with pharaohs adding monumental structures and grand halls.

- Later Adaptations: Even during periods of decline, Karnak continued to be modified and adapted by different rulers.

This table concisely overviews Karnak’s early development, highlighting the key phases and influences that shaped this extraordinary complex.

Karnak Temple Layout and Major Sections of Karnak

You’re looking for a comparison of the different precincts and structures within Karnak Temple! It’s fascinating to see how they reflect variations in dedication, architectural styles, and purposes. Here’s a table summarizing key aspects:

| Feature | Precinct of Amun-Re | Temple of Mut | Temple of Khonsu | Festival Halls & Chapels |

| Deity | Amun-Re (king of the gods) | Mut (mother goddess) | Khonsu (moon god) | Varies (Thutmose III, Osiris, Ptah, etc.) |

| Engineering | – Massive pylons and courts<br> – Hypostyle Hall with colossal columns<br> – Obelisks requiring precise transportation and erection | – Artificial lake (Isheru) requiring hydrological planning<br> – Avenue of sphinxes | – Well-preserved pylon and gateway | – Akh-Menu with complex layout<br> – Varied chapel designs |

| Architecture | – Axial layout with processional routes<br> – Grand scale and imposing structures<br> – Hypostyle hall with varied column styles | – Smaller scale than Amun-Re precinct<br> – Crescent-shaped sacred lake<br> – Use of sandstone and mudbrick | – Unified design primarily from Ramses III’s reign<br> – Use of sandstone | – Diverse architectural styles<br> – Integration with landscape |

| Astronomy | – Possible solar alignments (debated)<br> – Orientation towards the sunrise on specific dates | – Possible lunar alignments (speculative) | – Potential lunar connections (speculative) | – Possible astronomical alignments in some structures |

| Art & Decoration | – Reliefs depicting pharaohs, battles, and religious scenes<br> – Colossal statues of pharaohs and gods<br> – Use of vibrant colors | – Reliefs focusing on Mut and her mythology<br> – Sekhmet statues (protective function) | – Well-preserved reliefs of Ramses III and Khonsu<br> – Astronomical ceiling decorations in sanctuary | – Reliefs depicting festivals, offerings, and mythology<br> – Botanical scenes in Thutmose III’s Festival Hall |

Export to Sheets

Key Takeaways:

- Amun-Re Precinct: The grandest and most complex, reflecting Amun-Re’s status as king of the gods. Showcases impressive engineering and a variety of architectural and artistic styles.

- Temple of Mut: Smaller in scale but significant for its association with a powerful female deity. Notable for its sacred lake and the presence of numerous Sekhmet statues.

- Temple of Khonsu: A well-preserved example of a New Kingdom temple with a unified design. Potentially linked to lunar observations.

- Festival Halls & Chapels: These demonstrate the diversity of religious practices and architectural forms at Karnak. They are often associated with specific pharaohs or deities.

By comparing these different elements of Karnak, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity and richness of ancient Egyptian religion, architecture, and artistry.

Karnak Temple The Precinct of Amun-Ra

You’re interested in a focused look at the Precinct of Amun-Re within the Karnak Temple complex! It’s truly the heart of Karnak and a marvel of ancient Egyptian architecture and religious expression. Here’s a table outlining its key features:

| Feature | Description | Picture Example |

|---|---|---|

| Pylons | Massive monumental gateways, often decorated with scenes of pharaohs’ victories and religious processions. The 1st pylon, though unfinished, is the largest at Karnak. |

first pylon of the Precinct of AmunRe, with its massive scale and reliefs.

|

| Courts | Large open spaces surrounded by colonnades or walls were used for processions and gatherings. |

one of the courts within the Precinct of AmunRe, showing the surrounding colonnades and obelisks.

|

| Great Hypostyle Hall | A vast hall with 134 colossal columns arranged in 16 rows. The central 12 columns are the tallest, creating a raised central nave. Decorated with intricate reliefs and inscriptions. |

Great Hypostyle Hall, capturing the forest of columns and the play of light and shadow.

|

| Obelisks | Tall, four-sided pillars, tapering to a pyramidal top, symbolizing the sun god Ra. Hatshepsut’s obelisk in this precinct is the tallest surviving ancient obelisk. |

Hatshepsut’s obelisk, towering over the surrounding structures.

|

| Statues | Colossal statues of pharaohs (e.g., Ramses II), gods (e.g., Amun-Re), and sphinxes were placed throughout the precinct to convey power and divine presence. |

colossal statue of Ramses II within the Precinct of AmunRe.

|

| Sacred Lake | A large artificial lake is used for ritual cleansing and symbolic reenactment of the sun god’s journey. | |

| Smaller Temples | The precinct includes smaller temples and chapels dedicated to specific deities or aspects of Amun-Re, such as the Temple of Ptah. |

Temple of Ptah within the Precinct of AmunRe.

|

| Reliefs & Inscriptions | The walls and columns are covered in intricate reliefs and hieroglyphic inscriptions depicting religious scenes, pharaohs’ accomplishments, and offerings to the gods. These offer valuable historical insights. |

closeup of a relief depicting a pharaoh making an offering to AmunRe.

|

Key Points:

- The Precinct of Amun-Re is the largest and most significant part of Karnak Temple.

- Its layout and decoration reflect the Egyptians’ understanding of the cosmos and the pharaoh’s role as an intermediary between the gods and the people.

- It’s a testament to ancient Egyptian engineering, architecture, and artistry, showcasing their ability to create monumental structures with intricate details.

Exploring the Precinct of Amun-Re is like stepping back in time, offering a profound sense of awe and wonder at the achievements of this ancient civilization.

Karnak Temple of Mut

You’re interested in a closer look at the Temple of Mut within the vast Karnak complex! It’s a fascinating place with unique features and a rich history connected to a powerful female deity. Here’s a table summarizing its key aspects:

| Feature | Description | Picture Example |

|---|---|---|

| Dedication | Dedicated to Mut, the ancient Egyptian mother goddess, associated with creation, protection, and nurturing. She was a key member of the Theban Triad (Amun, Mut, Khonsu). |

relief depicting Mut, wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt.

|

| Location | Situated south of the main Amun-Re precinct at Karnak, connected by an avenue of ram-headed sphinxes. |

avenue of ramheaded sphinxes leading to the Temple of Mut.

|

| Sacred Lake (Isheru) | A crescent-shaped lake surrounded the temple. It symbolized the primeval waters of creation and Mut’s association with rebirth and renewal. |

Sacred Lake (Isheru) surrounding the Temple of Mut, with the temple structures reflected in the water.

|

| Temple of Mut | The main temple within the complex features a pylon, courts, a hypostyle hall, and a sanctuary. It follows the typical layout of New Kingdom temples but on a smaller scale than the Temple of Amun-Re. |

pylon and entrance to the main Temple of Mut.

|

| Contra Temple | A smaller temple located to the south of the main temple. Its exact purpose is debated, but it may have been dedicated to a consort of Mut or used for specific rituals. |

Contra Temple at the Temple of Mut complex.

|

| Sekhmet Statues | Hundreds of statues of Sekhmet, the lion-headed goddess of war and healing, were found within the temple complex. They may have had a protective function, warding off evil or disease. |

group of Sekhmet statues within the Temple of Mut.

|

| Reliefs & Inscriptions | The temple walls are adorned with reliefs and inscriptions depicting Mut, scenes from her mythology, and pharaohs making offerings to her. These provide valuable insights into religious beliefs and practices associated with the goddess. |

relief from the Temple of Mut, showing a pharaoh offering to Mut.

|

Key Points:

- The Temple of Mut is a unique and significant part of Karnak, dedicated to a powerful female deity.

- Its features, such as the sacred lake and the Sekhmet statues, distinguish it from other temples within the complex.

- It provides valuable insights into the worship of Mut and her role in Egyptian religion and society.

Exploring the Temple of Mut offers a fascinating glimpse into the diversity of ancient Egyptian religion and the importance of female deities within their pantheon.

Karnak Temple of Khonsu

You’re focusing on the Temple of Khonsu at Karnak! It’s a beautifully preserved structure with a distinct atmosphere and some fascinating features. Here’s a table outlining its key aspects:

| Feature | Description | Picture Example |

|---|---|---|

| Dedication | Dedicated to Khonsu, the ancient Egyptian moon god, associated with the moon, time, healing, and protection. He was often depicted as a young man with a moon disk and crescent on his head. Part of the Theban Triad (Amun, Mut, Khonsu). |

relief depicting Khonsu with a moon disk and crescent on his head.

|

| Location | Situated within the Karnak complex, in the southwestern corner. Its gateway is at the end of an avenue of sphinxes that once connected Karnak with the Luxor Temple. |

Temple of Khonsu, showing its location within the Karnak complex.

|

| Pylon and Gateway | A massive pylon (gateway) with two towers decorated with reliefs depicting Ramses III before Khonsu. Ptolemy III Euergetes (Ptolemaic period) later added a grand gateway and enclosure wall, of which only the gateway remains. |

pylon of the Temple of Khonsu, with its impressive reliefs of Ramses III.

|

| Court | A large open court, surrounded by a colonnade with papyrus-shaped columns. |

court and colonnade of the Temple of Khonsu, showing the papyrusshaped columns.

|

| Hypostyle Hall | A hall with columns supporting the roof, featuring reliefs and inscriptions depicting Ramses III offering to Khonsu and other deities. |

hypostyle hall of the Temple of Khonsu, with its decorated columns and ceiling.

|

| Sanctuary | The innermost chamber, where the cult statue of Khonsu would have been housed. It features astronomical decorations on the ceiling. |

sanctuary of the Temple of Khonsu, showing the astronomical ceiling decorations.

|

| Reliefs & Inscriptions | The temple walls are adorned with well-preserved reliefs and inscriptions, which provide valuable insights into the religious beliefs and rituals associated with Khonsu. The reliefs also depict Ramses III’s military campaigns and his interactions with the gods. |

relief from the Temple of Khonsu, depicting Ramses III offering to Khonsu.

|

Key Points:

- The Temple of Khonsu is a remarkably complete example of a New Kingdom temple, primarily built by Ramses III.

- It showcases the typical architectural elements of an Egyptian temple: pylon, court, hypostyle hall, and sanctuary.

- Its reliefs and inscriptions provide valuable insights into the worship of Khonsu and the reign of Ramses III.

Visiting the Temple of Khonsu offers a wonderful opportunity to experience the atmosphere of an ancient Egyptian temple dedicated to the moon god and to appreciate the artistry and religious beliefs of the time.

Karnak Temple Festival Halls and Chapels

You’re interested in the festival halls and chapels of Karnak Temple! These structures offer a fascinating glimpse into the diverse religious practices and celebrations of ancient Egypt. Here’s a table outlining some of the most notable ones:

| Feature | Description | Picture Example |

|---|---|---|

| Festival Hall of Thutmose III | Located in the central part of the Amun-Re precinct. Built to celebrate the pharaoh’s jubilee (Sed festival), a ritual reaffirming the pharaoh’s power and divine right to rule. Contains unique features like a botanical garden and “Hall of Ancestors.” |

Festival Hall of Thutmose III, with its botanical reliefs and columns.

|

| Akh-Menu | Situated to the east of the main temple complex. A “festival hall” constructed by Thutmose III, possibly used for religious ceremonies and royal celebrations. Includes a peristyle court, a hypostyle hall, and a sanctuary. |

AkhMenu, showing its peristyle court and hypostyle hall with tentpolelike columns.

|

| Chapel of Osiris-Ptah-Neb | A small chapel dedicated to Osiris, Ptah, and Neb (a local Theban god). Contains interesting reliefs depicting the mummification process. |

Chapel of OsirisPtahNeb, with its reliefs depicting the mummification process.

|

| White Chapel of Senusret I | One of the oldest structures at Karnak, built by Senusret I of the Middle Kingdom. Made of white limestone and decorated with reliefs depicting the king making offerings to the gods. |

White Chapel of Senusret I, highlighting its white limestone construction and reliefs.

|

| Chapels of the Hearing Ear | Small chapels dedicated to Ptah, the god of craftsmen, are located near the Sacred Lake. They were believed to be places where people could come to have their prayers heard by god. |

one of the Chapels of the Hearing Ear, showing its small size and proximity to the Sacred Lake.

|

Key Points:

- Diversity of Purposes: The festival halls and chapels served various purposes, from celebrating royal jubilees to honoring specific deities and providing spaces for private worship.

- Architectural Variations: They showcase a range of architectural styles and features, reflecting different periods and influences.

- Religious Insights: The decorations and reliefs within these structures offer valuable insights into ancient Egyptian religious beliefs, rituals, and festivals.

Exploring these festival halls and chapels provides a deeper understanding of the rich tapestry of religious and cultural practices that unfolded within the vast complex of Karnak Temple.

Karnak Temple Religious and Cultural Significance

You’re looking to delve deeper into the profound meaning behind Karnak Temple! It was far more than just a collection of impressive structures; it was a place where the ancient Egyptians connected with their gods, celebrated their culture and expressed their understanding of the universe. Here’s a table summarizing its key religious and cultural significance:

| Aspect | Description | Picture Example |

|---|---|---|

| House of the Gods | Karnak was considered the “most select of places,” the earthly dwelling of Amun-Re, king of the gods. It was a place where humans and gods could interact, where pharaohs sought legitimacy, and where ordinary people came to worship and seek divine favor. |

grand procession of priests carrying a statue of AmunRe through Karnak Temple, symbolizing the god’s presence and the interaction between the divine and the human.

|

| Theban Triad | The temple complex honored the Theban Triad: Amun-Re, his consort Mut, and their son Khonsu. Each deity had their own precinct within Karnak, reflecting their roles in the cosmos and Egyptian society. |

relief depicting the Theban Triad: AmunRe, Mut, and Khonsu, showcasing their relationship and importance in Egyptian religion.

|

| Cosmic Order | The temple’s layout and decoration mirrored the Egyptians’ understanding of the universe. The Sacred Lake represented the primeval waters of creation, the pylons marked transitions between realms, and the progression from outer courts to inner sanctuaries symbolized a journey toward the divine. | <br>

Sacred Lake at Karnak, with the temple reflected in its waters, symbolizing the primeval waters of creation and the cyclical nature of life and rebirth.

|

| Festivals and Rituals | Karnak was a hub of religious activity, hosting grand festivals and daily rituals. These ceremonies, including processions, offerings, and sacred dramas, reinforced the connection between the gods, the pharaoh, and the people. | <br>

relief depicting a pharaoh making offerings to the gods, demonstrating the importance of ritual in maintaining cosmic order.

|

| Royal Power and Piety | Pharaohs used Karnak to legitimize their rule, associating themselves with the gods and demonstrating their piety through monumental constructions and lavish offerings. | <br>

relief depicting a pharaoh presenting offerings to the gods, demonstrating their piety and role as intermediary between the divine and the human.

|

| Artistic Expression | Karnak is a masterpiece of Egyptian art and architecture. Its colossal statues, intricate reliefs, and towering obelisks showcase the creativity and skill of ancient Egyptian artists and architects. | <br>

intricate reliefs on the walls of the Great Hypostyle Hall, depicting scenes from mythology and religious rituals.

|

| Historical Record | The temple’s inscriptions and decorations provide information about Egyptian history, mythology, and daily life. They serve as a valuable historical record, preserving the stories and beliefs of a civilization that thrived for millennia. | <br>

relief depicting scenes from daily life in ancient Egypt, offering insights into their customs and practices.

|

| National Identity | Karnak was a source of pride and identity for the ancient Egyptians. It symbolized their religious devotion, cultural achievements, and connection to their land and history. |

modernday Egyptians visiting Karnak, expressing their connection to their heritage and the enduring legacy of the temple.

|

Karnak Temple stands as a testament to the enduring power of religion, the grandeur of ancient Egypt, and the human desire to connect with the divine. It continues to inspire awe and wonder, offering a glimpse into a world where spirituality, art, and architecture intertwined to create a masterpiece of human civilization.

Karnak Temple’s Later History and Decline

You’re interested in the later chapters of Karnak Temple’s long history! It’s a period marked by changing religious landscapes, political shifts, and ultimately, a decline in the temple’s prominence. Here’s a table summarizing those key events:

| Period | Key Events and Transformations | Picture Example |

|---|---|---|

| Late Period (664-332 BCE) | – Decline of Thebes: Thebes loses its political dominance, leading to a decrease in Karnak’s importance and a reduction in large-scale construction. <br> – Religious Shifts: Changes in religious practices and the rise of new cults influence the temple’s development. |

smaller temple or chapel from the Late Period at Karnak, reflecting the reduced scale of construction compared to earlier periods.

|

| Kushite Period (747-656 BCE) | – Kushite Revival: Kushite pharaohs from Nubia conquer Egypt and restore parts of Karnak, reflecting their reverence for Amun. <br> – New Constructions: They add new structures and make modifications to existing ones, leaving their mark on the temple complex. |

structure or inscription at Karnak attributed to the Kushite pharaohs, showcasing their influence on the temple.

|

| Ptolemaic Period (305-30 BCE) | – Ptolemaic Adaptations: The Ptolemaic rulers, of Greek origin, continue to use and modify Karnak. <br> – Greek Influences: They build new temples and incorporate Greek architectural elements into existing structures. |

structure from the Ptolemaic period at Karnak, showing the incorporation of Greek architectural features, such as columns with different styles.

|

| Roman Period (30 BCE – 391 CE) | – Decreased Religious Significance: Under Roman rule, Karnak’s religious importance declines further. <br> – Maintenance and Limited Expansion: The Romans focus on maintaining order and extracting resources, with limited new construction at Karnak. |

Romanera inscription or structure at Karnak, possibly indicating repairs or minor additions.

|

| Christian Era (4th Century CE) | – Rise of Christianity: The spread of Christianity leads to the gradual decline of traditional Egyptian religion. <br> – Temple Closure: The Roman emperor Theodosius I officially closes pagan temples in 391 CE, leading to the abandonment of Karnak. <br> – Christian Appropriation: Some parts of Karnak are repurposed as Christian churches. |

Christian paintings or inscriptions on the walls of a structure at Karnak, such as the Festival Hall of Thutmose III, illustrating its repurposing as a church.

|

| Abandonment & Rediscovery | – Decline and Decay: Karnak is largely abandoned and falls into disrepair. Natural forces, earthquakes, and the reuse of its stones for other building projects contribute to its decline. <br> – Rediscovery and Excavation: European explorers and scholars rediscover and document Karnak in the 18th and 19th centuries, leading to archaeological investigations that continue to this day. | <br>

collapsed section of Karnak Temple, showing the effects of time and neglect.

|

This table highlights the key transformations and challenges that Karnak Temple faced in its later history, ultimately leading to its decline but also paving the way for its rediscovery and appreciation in modern times.

Karnak Temple Legacy and Modern-Day Significance