Filippo Brunelleschi, Mimar Sinan, and Sir Christopher Wren: Architecture

Here’s an overview of Filippo Brunelleschi, Mimar Sinan, and Sir Christopher Wren, three monumental figures in the history of architecture, each representing the pinnacle of design and engineering in their respective eras and regions:

Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446, Italian Early Renaissance)

- Era and Style: Brunelleschi is considered a founding father of Renaissance architecture. He broke decisively with the Gothic tradition, reintroducing classical Roman architectural principles of proportion, harmony, and modularity. He also famously “rediscovered” the principles of linear perspective, which revolutionized art and architecture.

- Key Architectural Innovations:

- The Florence Cathedral Dome (Duomo di Santa Maria del Fiore): His undisputed masterpiece. He ingeniously designed and built a massive, self-supporting dome without traditional centering (scaffolding), utilizing an innovative double-shelled structure and a herringbone brick pattern. This was an unprecedented engineering feat that solved a problem that had stumped architects for over a century, becoming a symbol of Renaissance humanism and ingenuity.

- Modular Design and Classical Elements: In buildings like the Ospedale degli Innocenti and the Basilicas of San Lorenzo and Santo Spirito, he utilized a rational, modular system based on simple geometric forms (squares, circles), emphasized clarity, proportion, and incorporated classical elements like columns, pilasters, and round arches in a new, harmonious way.

- Legacy: His work laid the groundwork for the entire Renaissance architectural movement, influencing generations of architects and setting the standard for classical revival in Western architecture. He was also a skilled sculptor and military engineer.

Mimar Sinan (c. 1489/1490–1588, Ottoman Empire)

- Era and Style: Sinan was the chief Ottoman architect and civil engineer during the classical period of Ottoman architecture, serving three sultans (Suleiman the Magnificent, Selim II, and Murad III). He masterfully evolved and refined the Ottoman architectural style, transforming it into a highly sophisticated and recognizable form.

- Key Architectural Innovations:

- Centralized Dome Structures: Sinan’s primary achievement was perfecting the centralized dome mosque, seeking to surpass the scale and ingenuity of the Byzantine Hagia Sophia while introducing greater harmony and spaciousness.

- Integration of Complex Elements: He was a master of integrating vast domes, cascading semi-domes, slender minarets, and intricate interior ornamentation (especially Iznik tiles) into cohesive and awe-inspiring complexes.

- Urban Planner and Engineer: Beyond mosques, he designed hundreds of diverse structures, including bridges, aqueducts, madrasas (schools), hospitals, caravanserais, and baths, demonstrating his comprehensive skill in civil engineering and urban planning across the vast Ottoman Empire.

- Masterpieces: His most celebrated works include the Süleymaniye Mosque (Istanbul) and the Selimiye Mosque (Edirne), which he considered his ultimate masterpiece for its triumph of dome and space.

- Legacy: His prolific output and innovative designs defined classical Ottoman architecture, influencing architects for centuries within the Islamic world and beyond. He is often referred to as the “Michelangelo of the Ottomans.”

Sir Christopher Wren (1632–1723, England)

- Era and Style: Wren was a pivotal figure in the English Baroque style, transitioning English architecture from its medieval roots to a grand, classical tradition. Initially a brilliant scientist and astronomer, he turned to architecture after the Great Fire of London.

- Key Architectural Innovations:

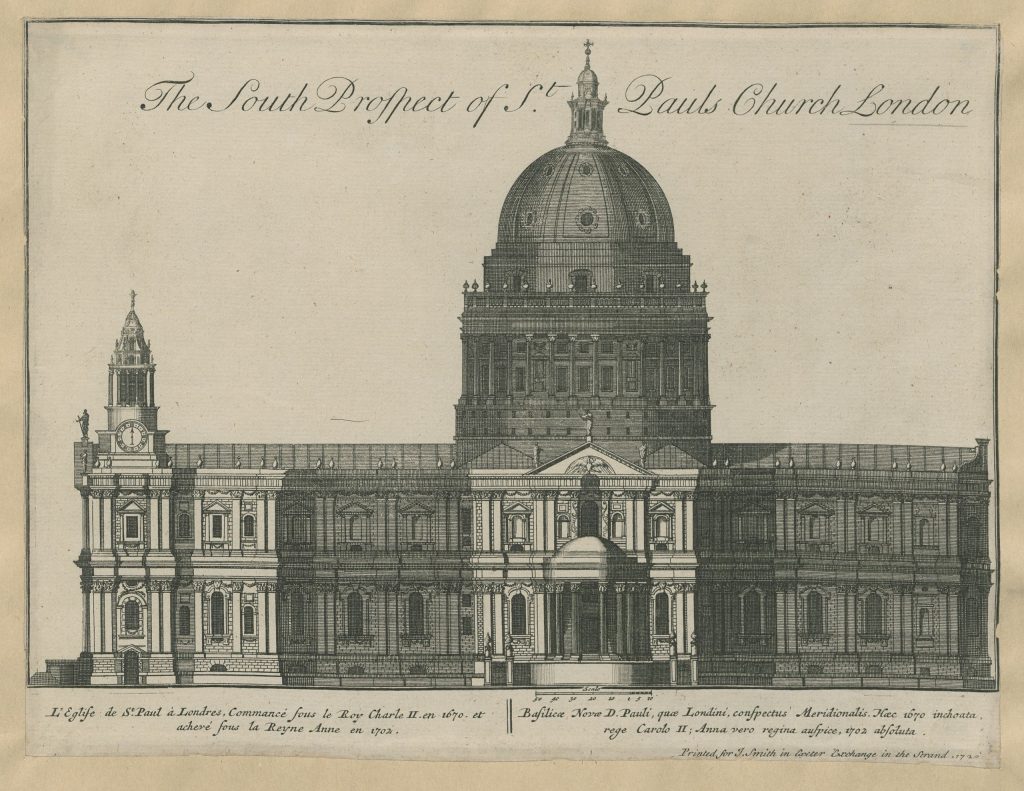

- Rebuilding London: His defining work was the rebuilding of London after the Great Fire of 1666. He designed over 50 churches, each with a unique and distinctive spire, helping to redefine the city’s skyline.

- The Dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral: His magnum opus, the dome of St. Paul’s, is a complex and ingenious structure, comprising three shells (an inner dome, a brick cone supporting the lantern, and an outer timber-framed dome). It’s a masterpiece of engineering and a dominant London landmark.

- Classical Grandeur with English Sensibility: Wren skillfully blended classical elements (columns, pediments, domes) with an English sensibility, creating dignified, robust, and often innovative designs for both religious and secular buildings.

- Masterpieces: His most famous works include St. Paul’s Cathedral, the Royal Hospital Chelsea, and the Old Royal Naval College at Greenwich.

- Legacy: Wren dramatically reshaped the architectural landscape of London and influenced English architecture for generations. He introduced a systematic and scientific approach to building, reflecting the Enlightenment era’s emphasis on reason and order.

In summary, these three architects, separated by centuries and geographies, each left an indelible mark on architectural history through their unparalleled skill, innovative engineering, and profound artistic vision, fundamentally shaping the built environment and influencing countless future generations of designers.

Filippo Brunelleschi, Mimar Sinan, and Sir Christopher Wren: Architecture Math

The great architects Filippo Brunelleschi, Mimar Sinan, and Sir Christopher Wren each revolutionized architecture through their profound understanding and application of mathematical principles. For them, architecture was not just an art but a “mathematical art,” where geometry, proportion, and structural mechanics were fundamental to beauty, stability, and innovation.

Filippo Brunelleschi: The Birth of Rational Space and Perspective

Brunelleschi (1377–1446) ushered in the Renaissance by reintroducing classical principles and a new scientific rigor to architecture.

- Linear Perspective: His most famous mathematical contribution was the rediscovery of linear perspective (around 1415). He systematically studied how to represent three-dimensional objects and space accurately on a two-dimensional surface. This involved understanding concepts like:

- A single vanishing point where parallel lines appear to converge.

- The diminution of objects in relation to their distance from the viewer.

- Proportional scaling to create the illusion of depth. This wasn’t just for drawing; it informed his architectural designs, ensuring internal spaces felt rational and harmonious to the viewer.

- Modularity and Proportion: In buildings like the Ospedale degli Innocenti and the Basilicas of San Lorenzo and Santo Spirito, he used strict modular systems. Designs were based on simple geometric forms (squares, circles) and precise mathematical ratios (e.g., 1:1, 1:2) between dimensions (width, height, bay spacing). This created a sense of clarity, order, and classical harmony.

- Dome Engineering: For the Florence Cathedral dome, his ultimate challenge, the math was groundbreaking:

- Self-supporting structure: He calculated how the dome could support itself during construction using an innovative double-shell design and a herringbone brick pattern. This involved complex calculations of thrust, compression, and the distribution of weight without external scaffolding.

- Catenary/Parabolic principles (pre-Hooke): While Robert Hooke would later formalize the catenary curve, Brunelleschi implicitly understood principles of ideal arch forms to design his dome’s structural integrity.

Mimar Sinan: The Optimization of Domed Space and Acoustics

Mimar Sinan (c. 1489/1490–1588) perfected classical Ottoman architecture by applying sophisticated geometric and structural principles to create vast, unified domed spaces.

- Geometric Optimization for Domes: Sinan’s lifelong ambition was to create larger, more harmonious dome spaces than the Byzantine Hagia Sophia. He used precise geometric calculations to:

- Distribute loads: His designs for domes (e.g., Şehzade, Süleymaniye, Selimiye) involved complex systems of main domes, semi-domes, and smaller domes, all mathematically proportioned to transfer loads efficiently down to supporting piers and buttresses.

- Achieve vast spans: The math involved understanding the forces of compression and tension in masonry, calculating the optimal curvature and thickness of dome shells to achieve unprecedented internal volumes.

- Symmetry and Balance: He applied principles of symmetry and balance not just aesthetically but also structurally, ensuring that loads were evenly distributed and opposing forces cancelled out.

- Acoustics: Sinan was a master of mosque acoustics. He used mathematical principles of sound reflection and absorption to optimize the sound within his vast prayer halls, often incorporating ceramic resonators (jars) into the walls and domes to amplify and clarify the Imam’s voice.

- Modular Systems and Scale: His complexes (külliyes) were often built on a modular system, with mathematical ratios governing the relationships between different buildings, ensuring overall harmony and functionality.

Sir Christopher Wren: Science, Geometry, and Structural Ingenuity

Sir Christopher Wren (1632–1723), a brilliant scientist and mathematician before he became an architect, infused his designs with a rigorous, almost experimental, mathematical approach.

- Scientific Approach to Architecture: Wren famously believed that “Natural Beauty is from Geometry, consisting in Uniformity (that is Equality) and Proportion.” He applied his understanding of physics, mechanics, and geometry directly to his architectural problems.

- Dome Engineering (St. Paul’s Cathedral): His masterpiece, St. Paul’s dome, is a testament to complex mathematical engineering:

- Triple-Shelled Structure: Wren designed a system of three domes (an inner decorative dome, a hidden brick cone supporting the lantern, and an outer timber-framed dome). The math involved ensuring that the hidden brick cone efficiently channeled the immense weight of the outer dome and lantern down to the foundations, functioning like a perfectly designed arch.

- Cubic Curve: Wren and his colleague Robert Hooke explored the properties of the catenary curve (“as hangs the flexible line, so but inverted will stand the rigid arch”) to find the ideal shape for arches and domes under compression. Wren used mathematical curves, such as a cubic curve (y=x3), to inform the shape of the structural brick cone in St. Paul’s, optimizing its stability and minimizing material.

- Load Distribution: Detailed calculations of vertical loads, horizontal thrusts, and the required thickness and buttressing were essential for the dome’s stability.

- Optimizing Church Interiors (Auditories): For his City churches, Wren employed geometry and proportion to create spaces that were not only visually stunning but also acoustically excellent and clear, ensuring that the congregation could hear the sermon distinctly. This involved understanding principles of sound propagation and line of sight.

- Modular Planning for Urban Scale: Wren’s overall plan for rebuilding London, though largely unrealized, showed a mathematical approach to urban planning, advocating for rational street grids and public spaces.

In summary, these three architects were not just artists; they were highly skilled mathematicians and engineers who used geometry, statics, dynamics, and material science to solve unprecedented structural problems, create new forms of beauty, and build enduring monuments that stand as a testament to the powerful synergy between mathematics and architecture.

Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446)

Filippo di ser Brunellesco di Lippo Lapi: Portrait by Masaccio, Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, 1423–1428

(Wiki Image By see filename or category – book: Elena Capretti, Brunelleschi, Giunti Editore, Firenze 2003, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6820703)

Filippo Brunelleschi Quotes

While Filippo Brunelleschi was a brilliant architect and engineer, he is not known for leaving behind a vast body of written work or personal philosophical statements that have survived as direct quotes, unlike some other historical figures. His genius was primarily expressed through his designs and his practical solutions to architectural challenges.

However, historians and biographers have inferred his character and approach from his actions, projects, and the writings of his contemporaries (like Antonio Manetti, his biographer, and Giorgio Vasari, who wrote extensively about Renaissance artists).

Here are some insights that reflect his spirit and the perceptions of him, even if not all are direct, verbatim quotes from him:

- On his iconic dome:

- (Paraphrased, regarding the impossibility of the dome’s construction) “It is impossible to build such a great cupola without centering, and impossible to build it without flying buttresses.” (This was the common belief he overturned.)

- (Attributed indirectly, reflecting his confidence) “There is no limit to what can be achieved if one is willing to try.”

- On his work ethic and secrecy (especially regarding the dome):

- (Reflecting his guarded nature) He was known to keep his plans and methods secret to prevent others from stealing his ideas. This isn’t a direct quote, but a description of his working style.

- “He never revealed his secrets, always working alone and in great secrecy.” (A common historical observation about him)

- On his practical approach and problem-solving:

- (On the egg experiment, to prove his method for the dome without revealing it directly) “He put a fresh egg upright on a piece of marble and said that whoever could make it stand up on its own, without touching anything other than the egg, should build the dome.” (This anecdote, while possibly apocryphal, illustrates his challenge-oriented, practical genius).

- “He did not draw much, but he did much of his work directly on the building site, solving problems as they arose.” (Describes his hands-on, practical approach.)

- On his legacy and Renaissance ideals:

- “He revived the true classical architecture.” (A historical judgment, not a direct quote from him, but captures his impact.)

- He believed in rationality and proportion – ideas that permeated his designs, even if he didn’t articulate them as catchy phrases.

It’s important to remember that much of what we know about Brunelleschi comes from later accounts and interpretations of his revolutionary work, rather than his own recorded words. His buildings themselves are his most eloquent testimony.

Filippo Brunelleschi YouTube Video

- How an Amateur Built the World’s Biggest Dome by National Geographic: 2,599,718 views (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z0_gD-s-m-k)

- Filippo Brunelleschi: Great Minds by SciShow: 357,927 views (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=blT5C_Y_y_k)

- The building of Brunelleschi’s cupola | David Battistella by TED Archive: 52,230 views (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X9c8hP-bQJc)

- Everything You’ll Ever Need to Know About… Filippo Brunelleschi by Muffy de Felice: 22,286 views (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i894y_l_C5Q)

- Linear Perspective: Brunelleschi’s Experiment by Smarthistory: 562,501 views (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o1N2jBw_I_Q)

Filippo Brunelleschi Books

For a single, definitive book on Filippo Brunelleschi, the best and most accessible choice is “Brunelleschi’s Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture” by Ross King.

As the founding father of Renaissance architecture, Brunelleschi’s life and work are the subjects of several excellent books. Here are the most essential options.

The Definitive Modern Account 🏛️

“Brunelleschi’s Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture” by Ross King

This is a modern classic and the most popular and engaging book on Brunelleschi’s greatest achievement. King tells the incredible story of how Brunelleschi, a brilliant but irascible goldsmith and clockmaker with no formal architectural training, solved the seemingly impossible puzzle of how to build the massive dome for Florence’s cathedral. It’s a gripping narrative of ingenuity, rivalry, and the dawn of the Renaissance.

The Classic Scholarly Biography

“Brunelleschi: The Complete Work” by Eugenio Battisti

For a more comprehensive and scholarly look at Brunelleschi’s entire career, this is the classic text. Battisti’s work is a detailed and authoritative study of all of Brunelleschi’s architectural projects, not just the dome. It examines his innovations in perspective, his other famous Florentine buildings (like the Pazzi Chapel and the Ospedale degli Innocenti), and his immense influence on the architects who followed him.

The Foundational Primary Source

“The Life of Brunelleschi” by Antonio di Tuccio Manetti

Written in the 1480s by a younger contemporary of Brunelleschi, this is the earliest and most important primary source on his life. While it contains some embellishments, it provides a unique near-contemporary account of his personality, his famous competition with Lorenzo Ghiberti for the Baptistery doors, and his revolutionary methods for constructing the dome. It is an indispensable historical document.

Filippo Brunelleschi History

Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral, towering above Florence, features the largest brick dome in the world and was realized by Brunelleschi.

(Wiki Image By bvi4092 – Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore from Palazzo Vecchio, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=73169115)

Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) was a towering figure of the early Italian Renaissance, often credited with fundamentally reshaping architecture and introducing groundbreaking concepts that defined the era. Born in Florence, Italy, his career spanned various disciplines before he became the architect he is celebrated as today.

Early Life and Training

Brunelleschi was born into a well-off Florentine family; his father was a notary. Although his father intended him to follow in his footsteps, Filippo was drawn to art. He initially trained as a goldsmith and sculptor, becoming a master in the Arte della Seta (silk merchants’ guild, which also included jewelers and metal craftsmen) in 1401.

A pivotal moment in his early career was the 1401 competition to design the second set of bronze doors for the Florence Baptistery. Brunelleschi competed against six other sculptors, most notably Lorenzo Ghiberti. While Brunelleschi’s triptych, “The Sacrifice of Isaac,” was highly praised, Ghiberti ultimately won the commission. Historians often cite this loss as a turning point that led Brunelleschi to shift his primary focus from sculpture to architecture.

Around 1402-1404, Brunelleschi reportedly traveled to Rome with his friend, the sculptor Donatello, to study ancient Roman ruins in detail. Unlike previous scholars who focused on literary accounts of antiquity, Brunelleschi meticulously measured and sketched the surviving structures, delving into their construction techniques, vaults, and domes. This direct study of classical architecture profoundly influenced his later designs.

Key Contributions to Renaissance Architecture

Brunelleschi’s architectural vision was revolutionary, marking a decisive break from the Gothic style that preceded him:

- The Dome of Florence Cathedral (Duomo di Santa Maria del Fiore): This is his most famous and significant achievement. The cathedral had been under construction for over a century, but no one knew how to span the massive octagonal opening without traditional wooden centering (scaffolding), which would have been impossibly expensive and structurally challenging. In 1420, Brunelleschi was named chief architect (capomaestro) of the dome project. He devised an ingenious double-shelled dome with a unique herringbone brick pattern and a sophisticated system of internal ribs, allowing it to be built without external support. This was an unprecedented feat of engineering that symbolized Renaissance ingenuity and remains a defining landmark of Florence. He also designed the machinery and hoists necessary to lift materials for its construction.

- Rediscovery of Linear Perspective: Around 1415, Brunelleschi “rediscovered” and rigorously demonstrated the mathematical principles of linear perspective. Through famous, though now lost, experiments involving painted panels and mirrors in Florence, he showed how to create the illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface by converging parallel lines to a single vanishing point. This discovery was transformative for both painting (influencing artists like Masaccio) and architectural drawing, allowing for more realistic and rational spatial representations.

- Modular Design and Classical Principles: Brunelleschi’s secular and religious buildings, such as the Ospedale degli Innocenti (Foundling Hospital), the Basilica of San Lorenzo, and the Pazzi Chapel, established key tenets of early Renaissance architecture:

- Clarity and Rationality: Designs based on simple geometric forms (squares, circles), precise mathematical proportions, and harmonious relationships between elements.

- Classical Elements: Reintroduction of classical orders (columns, pilasters), round arches, and harmonious proportions derived from ancient Roman models.

- Bichromatic Palette: Often used the stark contrast of grey pietra serena stone architectural elements against white plaster walls to emphasize structural lines and spatial clarity.

- Innovator and Engineer: Beyond his famous dome, Brunelleschi’s genius extended to mechanical engineering. He designed innovative hoists and machines for construction and other purposes (e.g., a riverboat for transporting marble, though it famously sank on its maiden voyage). He also contributed to the design of military fortifications for Florence.

Legacy

Filippo Brunelleschi died in Florence in 1446 and is buried in the crypt of the Florence Cathedral, a testament to his monumental achievement. He is widely considered one of the founding fathers of Renaissance architecture. His work profoundly influenced subsequent generations of architects and artists, establishing a new architectural language based on humanism, classical revival, and scientific principles. His buildings served as practical textbooks, shaping the trajectory of Western architecture for centuries to come.

The 10 top Filippo Brunelleschi Buildings. Table

Here is a table of the Top 10 buildings and structures associated with Filippo Brunelleschi, highlighting his most influential contributions to Renaissance architecture:

| # | Building/Structure | Location | Date | Significance |

| 1 | Florence Cathedral Dome (Il Duomo) | Florence, Italy | 1420–1436 | Engineering marvel; largest brick dome ever built. |

| 2 | Ospedale degli Innocenti | Florence, Italy | 1419–1445 | The first actual Renaissance building was an orphanage with classical features. |

| 3 | Basilica of San Lorenzo (interior) | Florence, Italy | 1421–1470 | Key example of proportion, clarity, and humanist spatial design. |

| 4 | Pazzi Chapel | Florence, Italy | c. 1441–1470 | Masterpiece of Renaissance harmony and mathematical precision. |

| 5 | Old Sacristy, San Lorenzo | Florence, Italy | 1421–1428 | First Renaissance-style chapel; prototype for central-plan churches. |

| 6 | Santa Maria degli Angeli (Rotunda) | Florence, Italy | 1434 (unfinished) | One of the earliest centralized-plan church designs in the Renaissance. |

| 7 | Church of Santo Spirito (plan) | Florence, Italy | c. 1434 | Designed with modular proportions, completed posthumously. |

| 8 | Church of Santa Maria del Fiore (Lantern) | Florence, Italy | 1436–1446 | Completed the dome with an innovative lantern structure. |

| 9 | Foundations of Fortifications in Pisa | Pisa, Italy | c. 1420s | Applied architectural skills to military engineering. |

| 10 | Pulpit of Santa Maria Novella (Design) | Florence, Italy | 1443 | While primarily known as a sculptor (Donatello was heavily involved), Brunelleschi is credited with elements of the architectural design of this famous pulpit. |

Filippo Brunelleschi Building: Florence Cathedral Dome (Il Duomo)

The Dome of the Florence Cathedral (Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore), affectionately known as “Il Duomo,” is Filippo Brunelleschi’s undisputed masterpiece and arguably the most iconic architectural achievement of the early Italian Renaissance. Its construction solved a monumental engineering challenge that had baffled architects for over a century and became a powerful symbol of Florentine ingenuity, civic pride, and the new spirit of the Renaissance.

The Challenge: A Century of Stumped Architects

When Brunelleschi returned to Florence around 1416, the vast octagonal drum of the cathedral was already built, but the gargantuan task of crowning it with a dome remained. Architects had no practical solution for spanning such a massive opening (over 45 meters or 147 feet in diameter) without the use of extensive and costly wooden centering (scaffolding) that would have required an entire forest and been structurally unsound at that scale. The very concept seemed impossible, leading many to believe that the dome could never be finished.

Brunelleschi’s Ingenious Solution

In 1420, after years of intense study and a famous competition (where he famously used an egg to illustrate his concept without giving away his secrets), Brunelleschi was awarded the commission. His genius lay in his deep understanding of classical Roman construction techniques (gained from studying ancient ruins), combined with his innovative engineering mind.

His solution involved several revolutionary elements:

- Double-Shelled Dome: Instead of a single massive dome, Brunelleschi designed an inner and outer shell. The lighter outer dome protected the inner one from the elements, while the inner dome provided structural support and formed the ceiling of the cathedral.

- Self-Supporting Construction: This was the most radical innovation. Brunelleschi devised a method where the dome would support itself as it was built, eliminating the need for complex internal scaffolding. He achieved this through:

- Herringbone Brick Pattern: The bricks were laid in a herringbone pattern, which acted like a series of interlocking arches, distributing weight and preventing slippage as the dome grew upwards.

- Horizontal “Chains” of Stone and Wood: Like rings on a barrel, continuous rings of stone and massive wooden timbers (secured with iron clamps) were embedded within the dome at various levels to counteract outward thrust and act as tension rings, preventing the dome from splaying apart.

- Segmented Construction: The dome was constructed in vertical segments, allowing individual sections to be completed without requiring support across the entire span.

- Innovative Lifting Machinery: Brunelleschi invented complex hoisting machines, powered by oxen, to lift the enormous quantities of stone, brick, and timber required for the dome’s construction. These machines were engineering marvels in themselves.

- No Pointed Arch (Gothic Influence): While the dome rises to a point, it’s not a pointed Gothic arch. Instead, it uses a unique shape derived from a pointed circular arc, which allowed it to rise more steeply and reduce outward thrust compared to a purely semicircular Roman dome of that scale.

Significance and Legacy

- Engineering Triumph: The dome, completed in 1436 (the lantern was added later, also to Brunelleschi’s design), was an unprecedented engineering feat. It demonstrated a mastery of geometry, statics, and construction that had not been seen since ancient Rome.

- Symbol of the Renaissance: Its construction became a powerful symbol of Florence’s wealth, ambition, and the burgeoning intellectual spirit of the Renaissance, where human ingenuity and rational thought could overcome seemingly impossible challenges. It represented a return to classical ideals of proportion and monumental scale, yet with innovative solutions.

- Architectural Model: The dome’s revolutionary design and construction techniques became a model for later architects, inspiring builders of grand domes for centuries, including those of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome and St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

- Catalyst for Architectural Theory: The challenges and solutions involved in its construction also spurred deeper theoretical discussions about architecture, contributing to the codification of Renaissance architectural principles.

The Florence Cathedral Dome stands as a testament to Filippo Brunelleschi’s genius, not just as an architect but as an inventor, engineer, and visionary who helped usher in a new era of human achievement.

Filippo Brunelleschi Building: Ospedale degli Innocenti

The Ospedale degli Innocenti (Foundling Hospital) in Florence, Italy, is a foundational work of Filippo Brunelleschi and a landmark in the history of Renaissance architecture. Commissioned by the powerful Arte della Seta (Silk Guild) in 1419, it served as an orphanage, providing care for abandoned children, and was completed in stages, with the famous facade largely finished by 1427.

Historical and Social Significance:

- Pioneering Social Institution: The Ospedale degli Innocenti was one of the first secular institutions in Europe dedicated exclusively to the care of abandoned children. Its construction reflected a new Renaissance emphasis on civic humanism and organized charity.

- Guild Patronage: The fact that a powerful guild, rather than just the Church, commissioned such a significant charitable and architectural project underscores the growing civic pride and responsibility in Renaissance Florence.

- Continuous Function: Remarkably, the institution operated as a foundling hospital continuously for over five centuries, from 1445 until 1875, and today houses the Museo degli Innocenti (Museum of the Innocents) dedicated to its history and the art collected over its operation, along with UNICEF offices.

Architectural Features and Significance:

The Ospedale degli Innocenti is celebrated for establishing many key features of early Renaissance architecture:

- Harmonious Arcade (Loggia): The most iconic feature is its long, elegant facade facing the Piazza della Santissima Annunziata. This nine-bay arcade, composed of slender Corinthian columns supporting semicircular arches, created a sense of harmony, order, and classical proportion that was a radical departure from the prevailing Gothic style.

- Modular Design: Brunelleschi applied a strict modular system to the facade. Each bay of the arcade is a perfect cube, with the distance between the columns, the height of the columns, and the depth of the loggia all based on a consistent unit. This emphasis on mathematical ratios and geometric simplicity contributed to the sense of rationality and clarity.

- Classical Elements: The use of classical columns (Composite order, a classical blend of Ionic and Corinthian), round arches (rather than Gothic pointed arches), and regularly spaced windows with classical pediments above the arches marked a return to Roman architectural vocabulary.

- Bichromatic Palette: Brunelleschi famously utilized a restrained palette of grey pietra serena (a local gray sandstone) for the architectural elements (columns, arches, cornices) against crisp white stucco walls. This contrast clearly articulated the structure and emphasized its geometric clarity, a style that became characteristic of Florentine Renaissance architecture.

- Andrea della Robbia Tondi: While not part of Brunelleschi’s original design, the glazed terracotta medallions (tondi) depicting swaddled babies, added by Andrea della Robbia around 1485, became a famous and endearing symbol of the hospital. These white and blue roundels are placed in the spandrels (the triangular spaces above each arch) and perfectly complement the architecture.

- Integration with Urban Space: The loggia not only provided a shelter for those bringing children but also created a welcoming, public space that opened onto the piazza, demonstrating an early Renaissance concern for the relationship between a building and its urban context.

The Ospedale degli Innocenti is considered a cornerstone of Renaissance architecture because it clearly articulated the fundamental principles that would define the movement: a return to classical forms, an emphasis on human scale and proportion, and a celebration of clarity, rationality, and harmony in design. It truly marked the “birth” of a new architectural era in Florence.

Filippo Brunelleschi Building: Basilica of San Lorenzo (interior)

The Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence, Italy, is a pivotal work by Filippo Brunelleschi, serving as a quintessential example of early Italian Renaissance church architecture. Commissioned by the powerful Medici family, who regarded it as their parish church and burial place, its construction began in 1419. Though completed after Brunelleschi’s death (with parts modified from his original vision), the interior largely reflects his revolutionary design principles.

Interior Architectural Features and Significance:

Brunelleschi’s design for the interior of San Lorenzo was a deliberate and radical departure from the Gothic style that preceded it, ushering in a new era of clarity, rationality, and classical harmony.

- Modular System and Proportion:

- The most striking feature of the interior is its rational, modular system. Brunelleschi based the entire layout on a square module, particularly visible in the side chapels. The nave’s dimensions (height, width, and bay spacing) are all derived from precise mathematical ratios, creating a sense of perfect proportion and order.

- This mathematical precision and geometric harmony were central to the Renaissance ideal of reflecting divine order in human creations.

- Bichromatic Palette: Pietra Serena and White Plaster:

- Brunelleschi masterfully used a restrained color palette, employing the grey local sandstone called pietra serena for all the architectural elements (columns, pilasters, arches, cornices, window frames).

- These grey elements stand in stark contrast to the crisp white stucco walls. This bichromatic scheme clearly articulates the building’s structure, allowing the viewer to easily “read” the architectural form and understand its geometric principles, a stark contrast to the often dark and ornately carved interiors of Gothic churches.

- Classical Elements Reintroduced:

- Columns and Arches: The nave is separated from the side aisles by elegant rows of slender Corinthian columns supporting semicircular arches. The use of round arches (as opposed to Gothic pointed arches) and the correct application of classical orders for the column capitals were innovations that reflected Brunelleschi’s meticulous study of ancient Roman architecture.

- Pilasters and Entablature: Along the side walls, pilasters (flattened columns) with Corinthian capitals rise to support a classical entablature (the horizontal elements above the columns, consisting of an architrave, frieze, and cornice). This creates a consistent classical vocabulary throughout the space.

- Coffered Ceiling: The nave is covered by a flat, coffered (paneled) wooden ceiling, a departure from the ribbed vaults of Gothic cathedrals. This further emphasizes the horizontal lines and contributes to the overall sense of spaciousness and classical restraint.

- Luminous and Serene Atmosphere:

- The interior is flooded with natural light from numerous windows, particularly those high up in the nave and in the dome over the crossing. This ample light, combined with the clear structure and restrained color, creates an atmosphere of serenity, clarity, and intellectual calmness.

- Sense of Rationality and Order:

- Walking through the nave, one experiences a profound sense of rational order and logical progression. The repetitive bays, the clear articulation of structural elements, and the harmonious proportions guide the eye and create a contemplative space that invites intellectual understanding as much as spiritual awe.

Significance:

The interior of the Basilica of San Lorenzo is a crucial benchmark in architectural history. It represents one of the earliest and most complete statements of Renaissance architectural principles applied to a church. Its elegant simplicity, mathematical rigor, and direct embrace of classical forms made it a prototype for subsequent Renaissance churches, deeply influencing generations of architects and solidifying Brunelleschi’s status as a visionary master.

Filippo Brunelleschi Building: Pazzi Chapel

The Pazzi Chapel (Italian: Cappella dei Pazzi) is a small, intimate chapel located within the first cloister on the southern flank of the Basilica di Santa Croce in Florence, Italy. Commonly credited to Filippo Brunelleschi, it is considered one of the masterpieces of early Renaissance architecture, showcasing the harmonious principles of the new style.

Historical Context and Patronage:

The chapel was commissioned by Andrea de’ Pazzi, a wealthy Florentine banker and head of the prominent Pazzi family, who were significant rivals to the powerful Medici family. Construction began around 1429, although work proceeded in stages due to various interruptions, including financial constraints and the Pazzi family’s later disgrace (following the Pazzi Conspiracy against the Medici in 1478). The chapel was largely completed after Brunelleschi’s death in 1446, with some elements, particularly the portico, possibly finished by other architects like Giuliano da Maiano, Michelozzo, or Bernardo Rossellino.

The chapel served multiple purposes: it was intended as a family burial place for the Pazzi, a meeting room (chapter house) for the Franciscan monks of Santa Croce, and a powerful symbol of the Pazzi family’s wealth, piety, and status.

Architectural Features and Significance:

The Pazzi Chapel is celebrated as a quintessential example of early Renaissance architecture, embodying Brunelleschi’s principles of clarity, rationality, and classical harmony:

- Modular System and Proportion: The chapel’s interior is defined by precise proportional relationships based on a central square module. The main space is essentially a rectangle, with a central square surmounted by a hemispherical dome, flanked by two symmetrical, barrel-vaulted wings. This geometric precision creates a sense of perfect balance and order, reflecting the Renaissance belief in mathematical harmony.

- Bichromatic Palette: Pietra Serena and White Plaster: Similar to his other works, Brunelleschi’s design prominently features a restrained color scheme. All architectural elements – columns, pilasters, arches, entablature, and cornices – are rendered in dark-grey pietra serena (a local sandstone), which stands out sharply against the crisp white stucco walls. This contrast clearly articulates the building’s structure, making its rational organization visually evident.

- Classical Elements: The design reintroduces classical architectural vocabulary:

- Corinthian Pilasters: Slender, fluted pilasters with Corinthian capitals line the walls, articulating the bays and supporting the entablature.

- Round Arches: Semicircular arches are used consistently, reflecting the classical Roman style.

- Dome: The central dome, like those in the Old Sacristy and the Florence Cathedral, is a hemispherical form, emphasizing geometric purity. It features ribs that converge at an oculus, letting in light.

- Luminous Interior: The chapel is well-lit by windows, particularly those around the perimeter of the dome. The interplay of light filtering through these openings on the white and grey surfaces enhances the clarity and elegance of the space.

- Subordination of Decoration to Architecture: While decorated, the ornamentation in the Pazzi Chapel is carefully integrated into the architecture.

- Terracotta Roundels: Glazed terracotta roundels by Luca della Robbia (and possibly Andrea della Robbia) adorn the pendentives of the dome (depicting the Four Evangelists) and the frieze below the dome (alternating with cherubim and the Lamb of God). Their vibrant blues stand out against the monochrome architecture, but they do not overwhelm the structural clarity.

- Astronomic Fresco: The small dome over the altar features a simple fresco depicting the constellations visible over Florence on July 4, 1442, reflecting the Renaissance interest in astronomy and the precise calculation of time.

- Portico/Facade: The chapel is fronted by an elegant portico. This six-columned portico, with its central arch and a smaller dome in its center adorned with Luca della Robbia’s glazed terracotta rosettes (bearing the Pazzi crest), serves as a classical entrance that frames the chapel’s main body. The authorship of this portico is debated, with some attributing it to later architects, though it generally aligns with Brunelleschi’s overarching style.

The Pazzi Chapel is revered for its almost “perfect” proportions, its serene atmosphere, and its clear expression of the intellectual and aesthetic ideals of the early Renaissance. It served as an influential model for later Renaissance architects, demonstrating how classical forms and mathematical harmony could create spaces of profound beauty and rational order.

Filippo Brunelleschi Building: Old Sacristy, San Lorenzo

The Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo (Sagrestia Vecchia) in Florence, Italy, is a profound and highly influential work by Filippo Brunelleschi, serving as a prototype for Renaissance sacred spaces. Commissioned by Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici, the patriarch of the powerful Medici family, it was intended as a burial chapel for his family and as a chapter house for the Basilica of San Lorenzo. Construction began around 1419 and was largely completed by 1428, making it one of Brunelleschi’s earliest and most complete statements of Renaissance architectural principles.

Historical Context and Patronage:

The Medici family’s patronage of the Old Sacristy was strategically significant. It was part of a larger rebuilding project for the Basilica of San Lorenzo, which the Medici adopted as their family church. Giovanni di Bicci’s decision to entrust Brunelleschi with this chapel allowed the architect to fully realize his innovative vision on a smaller, more manageable scale before applying it to the larger basilica nave. This early collaboration solidified the enduring relationship between the Medici and Brunelleschi, which would profoundly shape Florentine Renaissance art and architecture.

Architectural Features and Significance:

The Old Sacristy is celebrated for its clarity, rationality, and harmonious proportions, embodying the essence of early Renaissance design:

- Perfect Geometric Forms: The primary space of the sacristy is a perfect cube, topped by a hemispherical dome. This use of fundamental geometric shapes – the square and the circle – was central to Brunelleschi’s design philosophy, reflecting the Renaissance belief in the inherent beauty and divine order expressed through mathematics. The height of the walls from the floor to the base of the dome is equal to the width of the room, creating a 1:1 proportion that is aesthetically pleasing and intellectually satisfying. A smaller, square “scarsella” (altar chapel) with its own small dome projects from one side, acting as a miniature version of the main space.

- Bichromatic Palette: Pietra Serena and White Stucco: Brunelleschi’s signature use of grey pietra serena (a local Tuscan sandstone) for all architectural elements (columns, pilasters, arches, entablature, cornices) against stark white stucco walls creates a highly articulate and visually clear structure. This contrast enables the viewer to “read” the architectural framework and comprehend the geometric relationships that underpin the space.

- Classical Elements: The interior incorporates classical architectural vocabulary:

- Corinthian Pilasters: Slender, fluted pilasters with Corinthian capitals define the corners and articulate the wall surfaces.

- Round Arches: Semicircular arches are used to transition from the cube to the dome (through pendentives) and within the scarsella, reflecting a return to Roman forms.

- Entablature: A continuous entablature runs around the room, serving as a horizontal dividing line that further emphasizes the modularity and proportion of the space.

- Luminous Dome and Symbolic Sky: The main dome, often referred to as an “umbrella” or “melon” dome, is divided into twelve ribbed sections, each pierced by an oculus (round window) at its base. This design allows ample natural light to flood the space, creating a sense of lightness and spiritual elevation. The small dome over the altar chapel features a famous astronomical fresco (attributed to Giuliano d’Arrigo, also known as Pesello), depicting the constellations as they appeared over Florence on a specific date (likely July 4, 1442), reflecting the Renaissance’s fascination with science and the cosmos.

- Integration of Decoration: While Brunelleschi’s original design was quite austere, the chapel later received significant decoration by Donatello, including terracotta medallions in the pendentives (depicting the Four Evangelists) and bronze doors. These additions, while richer, were designed to complement rather than overwhelm Brunelleschi’s clear architectural framework.

Significance:

The Old Sacristy is considered a highly significant building for several reasons:

- Prototype for Renaissance Sacred Space: It set a powerful precedent for subsequent Renaissance church interiors and chapels, influencing architects for generations with its emphasis on clarity, proportion, and classical forms.

- Embodiment of Humanism: The rational, human-scaled proportions of the Old Sacristy reflect the humanist ideals of the Renaissance, celebrating human intellect and order.

- Brunelleschi’s Vision: It’s one of the few parts of the San Lorenzo complex fully completed under Brunelleschi’s direct supervision during his lifetime, making it a pure and unadulterated expression of his architectural genius.

The Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo stands as a testament to Brunelleschi’s revolutionary vision, demonstrating how a scientific approach to proportion and a return to classical forms could create spaces of profound beauty, intellectual clarity, and spiritual resonance.

Filippo Brunelleschi Building: Santa Maria degli Angeli (St. Mary of the Angels)

Santa Maria degli Angeli (St. Mary of the Angels), often referred to as the “Rotonda degli Scolari” due to its patrons, is a significant and revolutionary, though unfinished, church design by Filippo Brunelleschi in Florence, Italy. Commissioned by members of the Scolari family in 1434, it marked a radical departure from the traditional basilican church plan, instead embracing a centralized, octagonal form.

Historical Context and Patronage:

The church was intended for the Camaldolese monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli, a learned community in Florence that was a hub for humanist scholars. The Scolari family provided the bequest for its construction. Construction began in 1434 but was unfortunately abandoned around 1437 due to financial difficulties, as funds were diverted to support Florence’s war against Lucca. This left the building incomplete, with only the lower walls and foundations laid. While the structure was later incorporated into subsequent buildings, Brunelleschi’s original vision was never fully realized.

Architectural Features and Significance (Based on Brunelleschi’s Design):

Despite its unfinished state, Santa Maria degli Angeli is considered a pivotal work in Brunelleschi’s oeuvre and a crucial development in Renaissance architecture due to its innovative plan:

- Centralized Plan (Rotunda): This was the most revolutionary aspect of the design. Unlike his earlier basilican churches (like San Lorenzo and Santo Spirito), Santa Maria degli Angeli was conceived as a perfectly centralized, octagonal structure. This marked the first Renaissance church to be based on a central plan, directly inspired by ancient Roman models like the Pantheon (though it was a much smaller scale and different construction). The central plan symbolized divine perfection and celestial harmony, concepts that would become prominent in High Renaissance architecture (e.g., Bramante’s Tempietto).

- Eight Radiating Chapels/Recesses: The octagonal core was designed to be surrounded by eight ancillary, square-shaped spaces or “recesses,” effectively forming chapels or niches. One of these recesses was intended as the entrance, and another as the main altar, with the others serving as side chapels. This intricate arrangement created a dynamic and complex interior space around the central rotunda.

- Emphasis on Sculpted Masses: Unlike his earlier works, which often emphasized flat wall planes articulated by slender pilasters, Santa Maria degli Angeli featured piers whose planes are sculpted by semicircular hollows and engaged columns. This gave the structural components a more three-dimensional, “sculpted” quality, showing a move towards a more robust and massive classical vocabulary.

- Influence on Later Architects: Even in its incomplete state, Brunelleschi’s design for Santa Maria degli Angeli was known and studied by later Renaissance architects. It profoundly influenced subsequent centralized church designs, demonstrating the potential for complex, harmonious spaces rooted in classical principles. Architects like Giuliano da Sangallo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Donato Bramante would later explore and refine the centralized plan, often drawing inspiration from Brunelleschi’s pioneering work here.

- Rationality and Geometry: As with all of Brunelleschi’s designs, the plan of Santa Maria degli Angeli was based on rigorous mathematical principles and pure geometry, creating a logical and perfectly proportioned space, even if only in concept.

Legacy:

Santa Maria degli Angeli remains a testament to Brunelleschi’s visionary genius. Though never fully completed to his specifications, its groundbreaking centralized plan influenced the trajectory of Renaissance ecclesiastical architecture. It showcased Brunelleschi’s willingness to experiment with forms beyond the basilican plan, pushing the boundaries of contemporary architectural thought and solidifying his reputation as a true innovator who shaped the course of Western art and architecture. The extant lower walls and foundations provide a glimpse into his revolutionary vision.

Filippo Brunelleschi Building: Church of Santo Spirito (plan)

The Basilica of Santo Spirito in Florence, Italy, is considered Filippo Brunelleschi’s most mature church design and a refined culmination of his architectural principles from the early Renaissance. Commissioned by the Augustinian order, construction began in 1436 (though the original plan was approved earlier, around 1434). Although completed after Brunelleschi’s death in 1446, the church largely adheres to his meticulous and innovative plan, making it a crucial example of his later style.

The Plan: A Masterpiece of Rationality and Harmony

Brunelleschi’s plan for Santo Spirito is a profound expression of Renaissance ideals, emphasizing mathematical proportion, modularity, and a clear articulation of space, all inspired by his study of classical Roman architecture.

- Latin Cross Plan with Continuous Aisles: The church follows a traditional Latin Cross plan, but with a significant innovation: the side aisles are designed to be continuous around the entire perimeter of the church, including wrapping around the main altar and the entrance wall. This creates a fluid, uninterrupted flow of space, encouraging movement and contemplation throughout the entire perimeter.

- Original Vision for the Façade: In Brunelleschi’s original plan, this continuous aisle would have extended across the entrance wall, creating a large, columned foyer. He also planned for four entrances on the façade, rather than the traditional three, which would have seamlessly integrated the interior space with the piazza outside. While this radical façade was never built to his design (the current façade is much later and largely unfinished, and it features three doors), the interior clearly reflects his ambition for universal spatial articulation.

- Modular System and Perfect Proportions:

- Like San Lorenzo, Santo Spirito’s plan is based on a precise modular system derived from the square. The main nave bays are precisely half the size of the square crossing, and the side aisle bays are a quarter. This rigorous mathematical relationship ensures every part of the church is proportionally related to the whole, creating a sense of perfect harmony and intellectual order.

- The height of the nave columns is also perfectly proportional to their spacing, contributing to the sense of balance.

- Unified Interior Space with Consistent Arcades:

- The nave and aisles are defined by long rows of slender Corinthian columns supporting semicircular arches. These columns continue uninterrupted along the nave, around the transept, and even into the choir and chapels, creating a rhythmic and unified visual experience.

- The repetition of these bays, along with the consistent use of classical elements, contributes to a serene and contemplative atmosphere.

- Integrated Semicircular Chapels:

- A defining feature of Santo Spirito’s plan is the integration of 40 semicircular chapels that project outwards from the side aisles along the entire perimeter. Unlike San Lorenzo, where chapels were added in various forms, here they are consistently designed as small, apsidal niches, creating a beautiful undulating effect on the exterior (though later additions largely hide this exterior undulation).

- This continuous sequence of identical chapels reinforces the modularity and sense of order, ensuring no single chapel dominates.

- Bichromatic Palette (Pietra Serena and White Plaster):

- Although the plan itself doesn’t directly dictate color, Brunelleschi’s typical use of contrasting grey pietra serena for structural elements against white stucco walls is inherent in the design’s clarity. This highlights the architectural framework, making the rationality of the plan visually manifest.

Significance of the Plan:

- Culmination of Brunelleschi’s Ideas: Santo Spirito represents the most mature and refined expression of Brunelleschi’s Renaissance principles, moving beyond the more experimental aspects of his earlier works. It embodies his dedication to classical forms, mathematical harmony, and rational spatial organization.

- Influence on Future Designs: Its elegant modularity, continuous aisles, and integrated chapels made it an incredibly influential model for later Renaissance architects, providing a blueprint for harmoniously proportioned and rationally planned church interiors.

- Emphasis on Horizontal Flow: The continuous aisles and consistent rhythm of the columns create a strong sense of horizontal flow, leading the eye around the vast space, rather than forcing a singular focus on the altar as in some earlier churches.

The plan of the Basilica of Santo Spirito is a testament to Brunelleschi’s genius, showcasing his vision for a clear, elegant, and perfectly proportioned architectural space that epitomizes the intellectual and aesthetic ideals of the early Renaissance.

Filippo Brunelleschi Building: Church of Santa Maria del Fiore (Lanterna del Duomo di Firenze)

The Lantern of the Florence Cathedral Dome (Lanterna del Duomo di Firenze) is the crowning element of Filippo Brunelleschi’s magnificent dome of Santa Maria del Fiore. While the dome itself was largely completed by 1436, the addition of the lantern was the final, critical piece of Brunelleschi’s grand design, both aesthetically and structurally. Construction of the lantern began in 1446, the same year Brunelleschi died, and was completed posthumously by his student, Michelozzo di Bartolommeo, following Brunelleschi’s precise models and instructions.

Historical Context and Challenge:

Even after the main dome was finished, the vast oculus (opening) at its apex remained. A lantern was necessary to provide light to the cathedral’s interior and, crucially, to act as the keystone of the entire dome structure, pressing down on the converging ribs and helping to stabilize the massive masonry.

The challenge of designing and constructing the lantern was significant, especially given its immense weight and the need to lift its heavy marble components to such a great height. Brunelleschi had prepared models and drawings, but his death meant he wouldn’t see their completion.

Architectural Features and Significance:

- Classical Design: The Lantern is a classical structure, reflecting Brunelleschi’s deep understanding and revival of Roman architectural principles. It is an octagonal structure (mirroring the dome’s base) with a central columned temple-like form.

- Harmonious Proportion: It sits in perfect proportion to the dome below, rising elegantly and culminating in a golden ball and cross at its very peak. The classical elements like columns, pediments, and niches are meticulously proportioned.

- Structural Function:

- Keystone Effect: The immense weight of the lantern (estimated at hundreds of tons) acts as a crucial “keystone” that compresses the eight main ribs of the dome. This downward force helps to counteract the outward thrust of the dome’s segments, increasing its stability and integrity.

- Light Source: The open structure and windows of the lantern allow natural light to stream down into the cathedral’s crossing, illuminating the vast interior space directly beneath the dome.

- Material: The lantern is constructed primarily from white marble, which contrasts beautifully with the red tiles and white ribs of the main dome, adding to its visual prominence.

- Sculptural Elements: Niches within the lantern were designed to hold statues, although these were never fully realized. The use of sculpted forms and classical details adds to its richness.

- Crowing Glory: The Lantern completes the visual and structural narrative of the dome, providing a majestic finial to Brunelleschi’s masterpiece. The gilded copper ball and cross, installed by Andrea del Verrocchio (Leonardo da Vinci’s master) in 1471, sit atop the lantern, reaching a total height of 114 meters (374 feet) from the ground.

Legacy:

The Lantern of the Florence Cathedral Dome stands as a testament to Brunelleschi’s foresight and comprehensive architectural vision. Even from beyond the grave, his detailed plans and models ensured that this final, critical element of his grandest project was executed according to his exacting standards. It solidified the dome’s structural integrity and completed its iconic silhouette, making it an enduring symbol of Florentine ingenuity and the architectural triumph of the early Renaissance.

Filippo Brunelleschi Building: Foundations of Fortifications in Pisa

Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) was not only a master of grand civilian and religious architecture but also a highly skilled military engineer. His expertise in construction and mechanics was put to use in designing and improving fortifications, particularly during Florence’s frequent conflicts with rival city-states, including those involving Pisa.

While he didn’t build a single, monumental “Fortress of Pisa” in the same way he built the Florence Cathedral dome, Brunelleschi was actively involved in strengthening and innovating the fortifications in and around Pisa for the Florentine Republic.

Here’s what is known about his work on fortifications, including those related to Pisa:

- Strategic Importance of Pisa: Pisa was a crucial port city for Florence, connecting it to the sea via the Arno River. Control of Pisa was vital for Florentine commerce and defense, leading to numerous conflicts with other powers like Lucca and Genoa, and internal struggles. Therefore, fortifying the Pisan territory was a high priority for Florence.

- Rocca del Brunelleschi (Brunelleschi’s Fortress) in Vicopisano: This is perhaps the most well-documented example of his military engineering in the Pisan area.

- Context: After Florence conquered Vicopisano (a strategic town near Pisa) in 1406, Brunelleschi was commissioned in 1435 to design an impregnable fortress there.

- Features: His design was highly innovative, integrating a 12th-century tower (Torre di Santa Maria) into a new, formidable complex. He employed:

- Ingenious System of Drawbridges: Designed to isolate parts of the fortress if an enemy managed to breach certain sections, preventing a total takeover.

- Massive Crenelated Wall: A powerful wall descended from the main Rocca (fortress) down to the Arno River, ending in the Torre del Soccorso (Defense Tower). This innovative feature was designed to ensure that supplies and reinforcements could reach the fortress by river, even under siege conditions, thereby preventing isolation.

- Sophisticated Interior Defenses: The fortress included specialized rooms for provisions, an armory, and control.

- Significance: The Rocca in Vicopisano is considered a masterpiece of military engineering, showcasing Brunelleschi’s practical genius and his application of geometry and mechanics to defensive architecture. It successfully deterred attacks and remained a strong Florentine outpost.

- Involvement in Pisa’s Walls (c. 1424): Records indicate that Brunelleschi was in Pisa around 1424, supervising the fortification of specific sections of the Pisan walls, particularly near the Porta a Lucca gate. This suggests his direct involvement in reinforcing existing structures.

- Other Fortifications: Brunelleschi also designed or consulted on other fortifications in Tuscany, including those in Lastra a Signa, Malmantile, Castellina, and Rimini, indicating his recognized expertise in military architecture across the Florentine domain.

Brunelleschi’s work on fortifications, including those connected to Pisa, demonstrates that his genius extended beyond the aesthetic and structural challenges of domes and churches. He was a practical engineer deeply involved in the geopolitical realities of his time, applying his scientific understanding to design effective defensive structures that protected Florentine interests. The surviving portions of the Rocca in Vicopisano stand as tangible proof of his innovative contributions to military architecture.

Filippo Brunelleschi Building: Pulpit of Santa Maria Novella (Design)

The Pulpit of Santa Maria Novella in Florence, Italy, is a significant Renaissance work, and its architectural design is indeed attributed to Filippo Brunelleschi.

Historical Context and Patronage:

The pulpit was commissioned by the Rucellai family in 1443. It’s situated in the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, a prominent Dominican church in Florence. The Rucellai family was a prominent patron of Renaissance art and architecture, notably commissioning the facade of Santa Maria Novella from Leon Battista Alberti.

Brunelleschi’s Design Contribution:

While the carving of the marble reliefs and the execution of the pulpit’s upper part were carried out by Andrea di Lazzaro Cavalcanti, known as Buggiano (Brunelleschi’s adopted son and assistant), the architectural design and overall conception of the pulpit are credited to Brunelleschi.

Brunelleschi’s contribution is evident in:

- Classical Proportions and Form: The pulpit’s structure reflects his characteristic use of classical elements and harmonious proportions. It is not merely a decorative appendage but an architecturally integrated structure, embodying his principles of rationality and order.

- Modular Design: The overall form likely adheres to the modular principles Brunelleschi applied in his larger buildings like San Lorenzo and Santo Spirito, ensuring its elements relate proportionally to each other and to the space it occupies within the church.

- Integration of Architecture and Sculpture: Brunelleschi’s design provided a clear and coherent architectural framework within which Buggiano’s sculptural reliefs could be placed. This collaboration between architecture and sculpture was typical of the Renaissance, and Brunelleschi’s structural clarity provided an ideal setting for narrative art.

- Suspended Design: The pulpit is notable for its position, suspended from one of the nave piers by a supporting bracket. This innovative placement allowed for better visibility and audibility for the congregation, a practical consideration often associated with Brunelleschi’s functional approach to design.

Significance:

- Early Renaissance Example: The pulpit is a notable example of early Renaissance design, illustrating how Brunelleschi’s architectural ideas were applied to even the smallest, functional elements within a larger Gothic church.

- Influence on Later Pulpits: Its design, emphasizing clarity and classical form, influenced subsequent pulpit designs in the Renaissance.

- Historical Moment for Galileo: The pulpit also holds historical significance as it was from this very pulpit that the first verbal attack was made on Galileo Galilei (by Tommaso Caccini in 1614), contributing to the events that eventually led to his indictment by the Inquisition.

Thus, while Buggiano was the craftsman, the underlying architectural conception and the integration of classical logic into the pulpit’s form are attributed to the genius of Filippo Brunelleschi, making it another testament to his profound influence on Renaissance design.

Mimar Sinan (c. 1489/1490–1588)

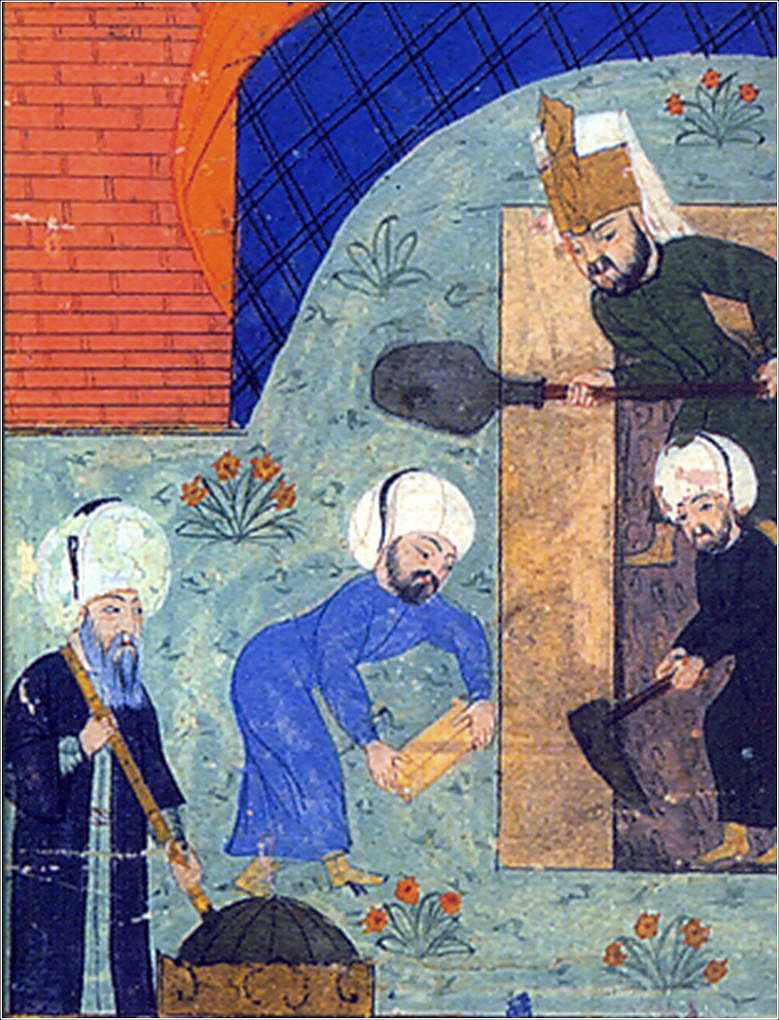

Possibly Mimar Sinan (left) at the tomb of Suleiman the Magnificent, 1566 manuscript

(Wiki Image By Scan, Painter: Nakkaş Osman – Cicek Kemal: The Great Ottoman Turkish Civilisation. Ankara 2000. p. 450., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3892789)

Mimar Sinan Quotes

Mimar Sinan (c. 1489/1490–1588) was a pragmatic and deeply religious man whose genius was primarily expressed through his monumental architectural creations. While he didn’t leave behind philosophical treatises in the same way some Western thinkers did, his autobiographical accounts, particularly the Tezkiretü’l Bünyan (Book of Buildings) compiled by his scribes, offer insights into his thoughts, his dedication to his craft, and his self-assessment.

Here are some attributed “quotes” or well-known statements reflecting his views and the descriptions of his work:

- On his Masterpieces and Artistic Progression (from Tezkiretü’l Bünyan):

- “My apprenticeship work is the Şehzade Mosque; my journeyman work is the Süleymaniye Mosque; and my masterpiece is the Selimiye Mosque.”

- Context: This is his most famous self-assessment, categorizing his three grandest imperial mosques and indicating his continuous architectural evolution and quest for perfection. It implies a conscious progression in his mastery of dome building and spatial integration.

- (Regarding the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne): “In this mosque, I have pulled up the dome, which used to be like a pumpkin on the side of the Hagia Sophia, and set it to a level that is now even with the dome of Hagia Sophia. In point of fact, the dome of Selimiye is 10 [cubits] higher than the Hagia Sophia.”

- Context: This highlights his lifelong ambition to surpass the Hagia Sophia, not just in size (though Selimiye’s dome is wider and higher) but in its structural rationality and the seamless integration of its interior space. He believed he achieved this in Selimiye.

- On his Engineering and Problem-Solving:

- “I have achieved an elevation that makes a new horizon for Istanbul.”

- Context: Reflecting on his many mosques and complexes that redefined the city’s skyline, particularly the Süleymaniye Mosque, which dominates one of Istanbul’s seven hills.

- “Those who see my structures, let them not doubt the sincerity of my intentions, for only by the Grace of Allah could I build these.”

- Context: Sinan, as a devout Muslim, often attributed his success to divine guidance, a common expression of piety in that era.

- On the Importance of the Craft and Purpose:

- “May those who look at my structures never be able to find any fault in their construction.”

- Context: This expresses his meticulous attention to detail, structural integrity, and enduring quality in his work, aspiring for perfection.

- “Our purpose is not to build a beautiful building, but to build a building that serves its purpose beautifully.”

- Context: While not a direct quote, this sentiment is inferred from his functional approach to architectural complexes, where mosques were surrounded by madrasas, hospitals, and soup kitchens, all serving the community.

- General Reflections (as recorded by his biographers/scribes):

- “All my works are proof of what I have achieved.”

- Context: A simple yet powerful statement reflecting his belief that his extensive portfolio of hundreds of buildings spoke for itself.

These insights, primarily drawn from his own reflections recorded by his scribes, reveal a master architect deeply committed to his faith, continuously striving for technical perfection, and profoundly aware of his historical legacy.

Mimar Sinan YouTube Video

- Ottoman Architect Mimar Sinan: The Master of Geometry | Architecture | Showcase by TRT World: 76,330 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=liiD4BwujMU)

- Gizemli Tarih: Mimar Sinan Özel | Kadimin Esrarı | TRT Belgesel by TRT Belgesel: 1,589,657 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vaqIaCFI3wo)

- Gizemli Tarih: Mimar Sinan | TRT Belgesel by TRT Belgesel: 258,625 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a7cu_RZfrPo)

- Is Mimar Sinan the Greatest Architect? by Hikma History: 37,942 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EbOEf4OHQ5w)

- Mimar Sinan, the Great Ottoman Architect by Islamic Chronicles: 4,632 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R-xEXL2eZIc)

Mimar Sinan Books

For a single, definitive book on Mimar Sinan, a great modern choice is “The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire” by Gülru Necipoğlu.

As the chief architect of the Ottoman Empire at its zenith, Sinan’s work is a subject of immense architectural and historical importance. Here are some of the key books for understanding his life and genius.

The Definitive Modern Scholarly Work 🕌

“The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire” by Gülru Necipoğlu

This is the most comprehensive and authoritative scholarly work on Sinan available in English. Written by a leading Harvard professor of Islamic art and architecture, this monumental book is a deeply researched analysis of Sinan’s life, his architectural innovations, and the cultural context of the Ottoman court he served. It meticulously documents and analyzes his major works, including the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul and his masterpiece, the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne.

An Accessible Introduction

“Sinan: An Interpretation” by Doğan Kuban

This book by a prominent Turkish architectural historian offers a more concise and interpretive look at Sinan’s work. Kuban focuses on explaining Sinan’s design philosophy, his mastery of the dome, and his quest to create perfectly unified and harmonious interior spaces. It’s an excellent choice for readers seeking a more in-depth architectural analysis.

For a Broader Historical Context

“The Sultan’s Architect: The Life and Times of Mimar Sinan” by John Freely

This is a more narrative-driven and accessible book that places Sinan within the vibrant historical context of the 16th-century Ottoman Empire under Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent. While less architecturally detailed than the other books, it provides an excellent feel for the political, social, and cultural world in which Sinan created his masterpieces.

Mimar Sinan History

Selimiye Mosque in Edirne, Turkey, built by Sinan in 1575

(Wiki Image By Khirashima – File:Ist-Ath_-_99.jpg, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=84991890)

Mimar Sinan, often hailed as the “Michelangelo of the Ottomans,” was the greatest architect and civil engineer of the classical Ottoman period. His prolific career spanned nearly 50 years under three powerful sultans, leaving an indelible mark on the Ottoman Empire’s landscape.

Early Life and Military Career (c. 1489/1490 – 1539)

- Origins: Sinan was born into a Christian family (believed to be of Armenian, Greek, or Albanian origin) in the village of Ağırnas near Kayseri in central Anatolia, likely around 1489 or 1490. His birth name was Joseph.

- Devşirme System: At around the age of 21, he was conscripted into the Janissary corps, the elite infantry units of the Ottoman army, through the devşirme system, which recruited young Christian boys from the Balkans and Anatolia, converted them to Islam, and trained them for state service.

- Military Engineer: Sinan received extensive training as a military engineer. He participated in numerous Ottoman campaigns, including the Siege of Belgrade (1521), the Battle of Mohács (1526), the Siege of Vienna (1529), and campaigns in Persia (1535), Rhodes (1522), Corfu, and Moldavia. During these campaigns, he distinguished himself by constructing bridges, fortifications, and other military structures, gaining practical experience in diverse building techniques and materials across a vast geographical area. His ability to quickly build complex structures like bridges across rivers (e.g., the Danube) during campaigns brought him to the attention of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.

Chief Court Architect (1539 – 1588)

- Appointment: In 1539, at around the age of 50, Sinan was appointed Chief Architect of the Ottoman Empire, a position he would hold for an extraordinary 50 years until his death. This appointment marked the beginning of the most productive and influential phase of his life, coinciding with the empire’s zenith.

- Prolific Output: Sinan’s output was immense, making him one of the most prolific architects in history. He is credited with designing and overseeing the construction of nearly 500 structures, including:

- Mosque Complexes (Külliyes): His most famous works, which often included mosques, madrasas (theological schools), hospitals, imarets (soup kitchens), hammams (public baths), caravanserais, and tombs, formed comprehensive urban centers.

- Bridges and Aqueducts: Major engineering feats like the Mağlova Aqueduct and the Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge (Višegrad, Bosnia).

- Palaces, Tombs, Schools, Bazaars, Fountains, and more.

- Architectural Evolution: Sinan consciously evolved his style throughout his career, often categorizing his major mosques into stages:

- Apprenticeship Work: Şehzade Mosque (Istanbul, 1548): Commissioned by Suleiman for his son, this mosque showcases a mastery of the central dome concept, surrounded by four half-domes, creating a highly symmetrical design.

- Journeyman Work: Süleymaniye Mosque (Istanbul, 1557): Built for Suleiman the Magnificent, this imperial mosque complex dominates Istanbul’s skyline. It’s a vast and harmonious complex demonstrating Sinan’s ability to integrate multiple functions into a unified design, arguably surpassing its inspiration, the Hagia Sophia, in its internal spatial harmony. It also boasts remarkable acoustics.

- Masterpiece: Selimiye Mosque (Edirne, 1575): Sinan himself regarded this as his finest work, a testament to his continuous quest for perfection. Its colossal dome, wider than the Hagia Sophia’s, and its four incredibly slender minarets represent a triumph of engineering and aesthetics, creating an astonishingly unified and light-filled interior space.

Legacy

Mimar Sinan died in Istanbul in 1588, at the remarkable age of 98, according to some accounts. He was buried in a modest tomb he designed for himself near the Süleymaniye Mosque.

- Definer of Ottoman Classical Style: His architectural concepts, particularly his refined use of centralized domes, cascading semi-domes, slender minarets, and the harmonious integration of multiple structures within complexes, set the standard for classical Ottoman architecture.

- Enduring Influence: His students and successors continued his traditions, and his influence extended across the Islamic world, even believed to have indirectly influenced structures like the Taj Mahal in India.

- Symbol of Ottoman Grandeur: His numerous enduring structures continue to shape the urban landscapes of modern Turkey and former Ottoman territories, serving as powerful symbols of the Ottoman Empire’s artistic and engineering prowess at its height. He is a national hero in Turkey, with a fine arts university named after him in Istanbul.

The 10 top Mimar Sinan Buildings. Table

Here is a table of the Top 10 buildings by Mimar Sinan, the chief Ottoman architect and one of the greatest architects in history:

| # | Building/Structure | Location | Date | Significance |

| 1 | Süleymaniye Mosque | Istanbul, Turkey | 1550–1557 | The masterpiece mosque complex built for Sultan Süleyman symbolizes Ottoman power. |

| 2 | Selimiye Mosque | Edirne, Turkey | 1568–1575 | Considered Sinan’s most significant work, the perfect dome geometry is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. |

| 3 | Şehzade Mosque | Istanbul, Turkey | 1543–1548 | First major imperial commission; tomb of Süleyman’s son. |

| 4 | Mihrimah Sultan Mosque (Üsküdar) | Istanbul (Üsküdar), Turkey | 1543–1548 | One of the two mosques that Sinan built for the Sultan’s daughter. |

| 5 | Mihrimah Sultan Mosque (Edirnekapı) | Istanbul (Edirnekapı) | 1562–1565 | Striking use of light and symmetry; high hilltop location. |

| 6 | Rüstem Pasha Mosque | Istanbul, Turkey | 1561–1563 | Known for rich İznik tile decoration and innovative space use. |

| 7 | Kılıç Ali Pasha Mosque | Istanbul, Turkey | 1578–1580 | Inspired by Hagia Sophia, built for an Ottoman admiral. |