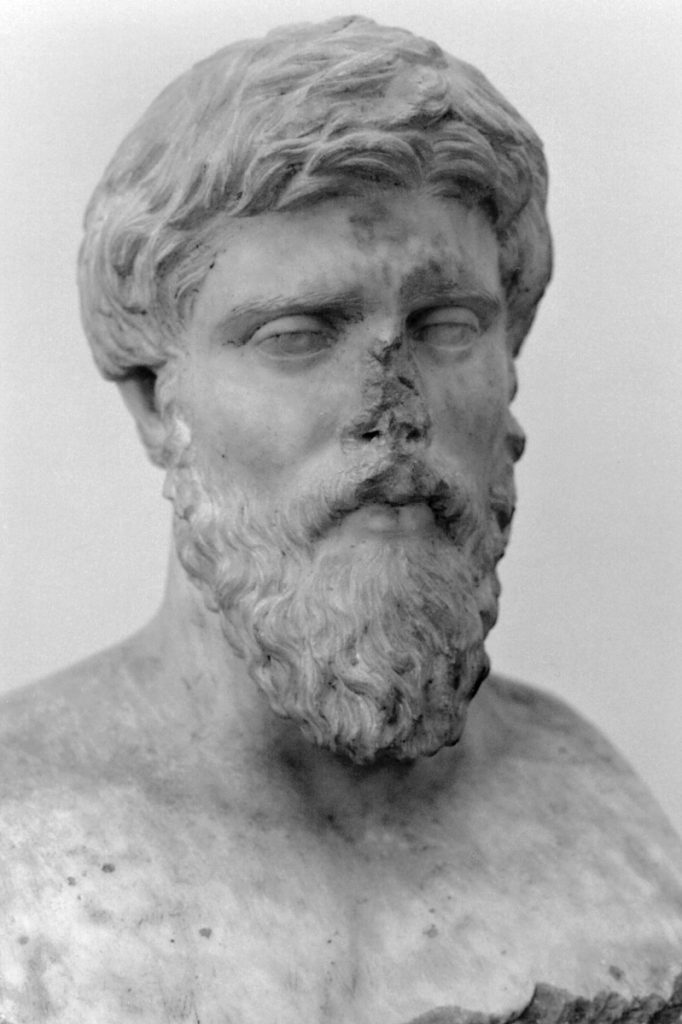

Plutarch

2nd-century bust from Delphi sometimes identified as Plutarch

(Wiki Image By Zde – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=56233390)

Plutarch Quotes

Plutarch’s writings, particularly the Parallel Lives and the Moralia, are filled with insightful observations on character, morality, leadership, education, and human nature. Here are some well-known quotes attributed to Plutarch:

- On Character and Biography:

- “For it is not Histories that I am writing, but Lives; and in the most illustrious deeds there is not always a manifestation of virtue or vice, nay, a slight thing like a phrase or a jest often makes a greater revelation of character than battles where thousands fall…” (From the introduction to the Life of Alexander in Parallel Lives – explaining his focus on character over mere events).

- On Education and the Mind:

- “The mind is not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be kindled.” (This quote perfectly captures his philosophy of education, emphasizing active engagement over passive reception. Found in Moralia: On Listening to Lectures).

- On Character and Habits:

- “Character is simply habit long continued.” (While the exact phrasing is debated, this sentiment reflects Plutarch’s emphasis on how repeated actions shape who we are.)

- On Adversity and Learning from Mistakes:

- “To make no mistakes is not in the power of man; but from their errors and mistakes the wise and good learn wisdom for the future.” (From the Life of Fabius Maximus in Parallel Lives).

- On Politics and Society:

- “An imbalance between rich and poor is the oldest and most fatal ailment of all republics.” (From the Life of Tiberius Gracchus in Parallel Lives).

- On Listening and Learning:

- “Know how to listen, and you will profit even from those who talk badly.” (From Moralia: On Listening to Lectures).

- On Friendship and Flattery:

- “I don’t need a friend who changes when I change and who nods when I nod; my shadow does that much better.” (From Moralia: How to Tell a Flatterer from a Friend).

- On Inner vs. Outer Reality:

- “What we achieve inwardly will change outer reality.” (Reflects his Platonist leanings and focus on internal virtue).

- On Art and Poetry:

- “Painting is silent poetry, and poetry is painting that speaks.” (Plutarch attributes this idea to Simonides of Ceos in Moralia: How the Young Man Should Study Poetry).

- On Rest and Leisure:

- “Rest is the sweet sauce of labour.” (From Moralia).

These quotes reflect Plutarch’s enduring focus on moral philosophy, the importance of character development, and the lessons that can be learned from studying the lives of influential individuals.

Plutarch YouTube Video

- Plutarch: Greek Philosopher by History Junkie: 17,517 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=94d9f7WW470)

- Plutarch’s Lives I: The Historians – Demosthenes and Cicero by Roman Roads Media: 17,975 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mHMr49FGmkM)

- Plutarch and Morals by Classics Confidential: 9,164 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nYWTQnOOB_0)

- Why Study Plutarch with Judith Mossman by University of Nottingham: 33,126 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w4awT9lx-oY)

- Why Study Plutarch and Delphi with Judith Mossman by University of Nottingham: 4,857 views (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yd9gGy9D7CY)

Plutarch Books

The most famous and essential book by the ancient Greek writer Plutarch is his collection of biographies known as the “Parallel Lives”.

Plutarch was a prolific author, but his surviving works are generally grouped into two major collections.

The Essential Biographies 🏛️

“Parallel Lives” (often published as “Plutarch’s Lives”)

This is Plutarch’s masterpiece and one of the most influential works of history ever written. The book is a series of biographies of famous Greek and Roman men, arranged in pairs to illuminate their common moral virtues or flaws. For example, he pairs the Greek orator Demosthenes with the Roman orator Cicero, and the great conqueror Alexander the Great with the Roman dictator Julius Caesar.

Plutarch was less concerned with a minute-by-minute historical account and more interested in the character, ethics, and moral choices of these great men. His work provides an unparalleled look into the personalities that shaped the ancient world.

Recommended Translations:

- For a modern, readable translation, look for the Penguin Classics editions, which are often published as “The Rise and Fall of Athens,” “The Rise of Rome,” etc.

- For the classic, literary translation, the “Dryden-Clough” translation is the most famous.

The Philosophical Essays 📜

“The Moralia”

This is a vast and eclectic collection of over 70 essays, speeches, and dialogues on a huge range of subjects. It includes Plutarch’s thoughts on ethics, religion, philosophy, politics, and personal conduct. While less famous than the Lives, the Moralia offers a deep insight into the everyday concerns and intellectual world of a highly educated Greek living under the Roman Empire.

Due to its size, the Moralia is almost always published in select volumes. A good place to start is the Penguin Classics edition titled “Essays,” which includes some of his most famous and accessible pieces, such as “On the Control of Anger” and “On Listening to Lectures.”

Plutarch History

Okay, let’s break down Plutarch and his relationship with history.

Plutarch (full name likely Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus, c. 46 CE – after 119 CE) was a prominent Greek writer, biographer, essayist, and philosopher who lived during the Roman Empire. While we often think of him in relation to history, it’s more accurate to call him a biographer and moralist who used historical figures as his subjects.

His most famous work, and the one most relevant to “history,” is:

- Parallel Lives (or Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans):

- Concept: This is a series of biographies of famous Greek and Roman individuals, arranged in pairs. Each pair typically consists of one Greek and one Roman figure chosen because Plutarch perceived similarities in their characters, careers, or fortunes. Examples include Alexander the Great paired with Julius Caesar, or Demosthenes with Cicero.

- Purpose: Plutarch’s primary goal was not to write a comprehensive historical account in the modern sense. Instead, he aimed to explore character and morality. He used the lives of these great men as case studies to illustrate virtues and vices, hoping to provide moral instruction and inspiration to his readers. He explicitly states in the introduction to his Life of Alexander, “For it is not Histories that I am writing, but Lives; and in the most illustrious deeds there is not always a manifestation of virtue or vice, nay, a slight thing like a phrase or a jest often makes a greater revelation of character than battles where thousands fall.”

- Historical Value: Despite his focus on character, the Lives are an invaluable historical source. Plutarch drew upon numerous earlier historical accounts, many of which are now lost. His work provides detailed accounts of events, political situations, social customs, and the personalities of key figures in Greek and Roman history.

- Structure: Most pairs follow a short comparison (synkrisis), explicitly drawing parallels and contrasts between the two figures.

- Influence: The Parallel Lives have profoundly impacted Western history, shaping perceptions of classical antiquity. They were a significant source for Shakespeare (e.g., Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra, Coriolanus), inspired figures during the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, and continue to be read today.

- Moralia (Moral Essays):

- Content: This is a comprehensive, eclectic collection of over 70 essays, dialogues, and treatises on various subjects, including ethics, religion, philosophy (particularly Platonism), politics, literature, education, and natural history.

- Historical Relevance: Although not strictly “history” books, several essays within the Moralia contain valuable historical information, anecdotes, discussions of customs (such as “Roman Questions” and “Greek Questions”), or philosophical reflections on historical events or figures. They provide insight into the intellectual and cultural milieu of Plutarch’s time.

Plutarch’s Approach:

- Focus on Character: As mentioned, his primary interest was in revealing the moral character of his subjects.

- Use of Sources: He utilized a wide range of sources, but was not always critical in the manner modern historians are. He sometimes included anecdotes and details more for their illustrative power regarding character than for their verifiable historical accuracy.

- Moralistic Tone: His writing often carries an overt moral lesson.

- Greco-Roman Perspective: As a Greek writer under Roman rule who became a Roman citizen, he navigated both cultures, often seeking parallels and demonstrating a deep respect for both traditions while also showing an evident pride in his Greek heritage.

In summary, while Plutarch wrote extensively about historical figures and events, his primary lens was biographical and ethical rather than purely historical investigation. His Parallel Lives remain a cornerstone for understanding ancient personalities and contain a wealth of historical information, even if read with an awareness of his specific aims and methods.

Plutarch: The Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans Contents. Table

Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans, also known as the Parallel Lives, typically presents biographies in pairs, one of a Greek and one of a Roman, followed by a comparison between the two. However, some editions list them sequentially and include the comparisons within the main body or at the end of each pair. There are also a few unpaired lives.

Here is a general overview of the contents, reflecting the paired structure:

| Greek Lives | Roman Lives | Comparisons (where applicable) |

| Theseus | Romulus | Comparison of Romulus with Theseus |

| Lycurgus | Numa Pompilius | Comparison of Numa with Lycurgus |

| Solon | Publicola | Comparison of Publicola with Solon |

| Themistocles | Camillus | Comparison not extant in surviving texts |

| Pericles | Fabius Maximus | Comparison of Pericles with Fabius |

| Alcibiades | Coriolanus | Comparison of Alcibiades with Coriolanus |

| Timoleon | Aemilius Paulus | Comparison of Timoleon with Aemilius Paulus |

| Pelopidas | Marcellus | Comparison of Pelopidas with Marcellus |

| Aristides | Marcus Cato (the Elder) | Comparison of Aristides with Marcus Cato |

| Philopoemen | Titus Flamininus | Comparison of Philopoemen with Flamininus |

| Pyrrhus | Gaius Marius | Comparison not extant in surviving texts |

| Lysander | Sulla | Comparison of Lysander with Sulla |

| Cimon | Lucullus | Comparison of Cimon with Lucullus |

| Nicias | Marcus Crassus | Comparison of Nicias with Crassus |

| Eumenes | Sertorius | Comparison of Eumenes with Sertorius |

| Agesilaus II | Pompey | Comparison of Agesilaus with Pompey |

| Alexander the Great | Julius Caesar | Comparison not extant in surviving texts |

| Phocion | Cato the Younger | Comparison not extant in surviving texts |

| Agis IV and Cleomenes III | Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus | Comparison of Agis and Cleomenes with the Gracchi |

| Demosthenes | Cicero | Comparison of Demosthenes with Cicero |

| Demetrius Poliorcetes | Mark Antony | Comparison of Demetrius with Antony |

| Dion | Marcus Junius Brutus | Comparison of Dion with Brutus |

Export to Sheets

Unpaired Lives (often included in some editions):

- Aratus

- Artaxerxes II

- Galba

- Otho

Note: The order of these lives might vary across different editions. Some editions include an introduction by the translator or editor, indices, and other supplementary material.

It is best to consult the book itself or its online listing to obtain the precise table of contents for a specific edition.

Plutarch: Theseus and Romulus

Theseus Pictures

Romulus Pictures

Theseus and Romulus YouTube Video

The Full Story of Theseus – Greek Mythology Stories in Comics …

The Founding of Rome: The Story of Romulus and Remus in …

Plutarch: Life of Theseus and Life of Romulus

Plutarch’s Lives of Theseus and Romulus are two of the most famous biographies within his larger work, Parallel Lives. In this collection, Plutarch paired notable Greek and Roman figures, examining their lives and characters to draw moral lessons and explore similarities and differences between their paths and achievements. Theseus, a legendary founder-hero of Athens, is paired with Romulus, the mythical founder of Rome.

Here’s a glimpse into each of these biographies and the comparison Plutarch draws between them:

Life of Theseus:

- Plutarch recounts the mythical birth and upbringing of Theseus, son of a mortal woman, Aethra, and the god Poseidon (or King Aegeus of Athens, depending on the version).

- He details Theseus’s journey from Troezen to Athens, during which he famously encounters and defeats various monstrous figures and bandits, such as Sinis, Sciron, and Procrustes, thus clearing the land for safer travel.

- The biography covers Theseus’s arrival in Athens, his recognition by his father Aegeus, and his confrontation with the Minotaur in Crete, where he famously slays the beast with the help of Ariadne.

- Plutarch discusses Theseus’s role in the unification of Attica, the abduction of Helen (which leads to the Trojan War), his friendship with Pirithous, and his eventual tragic end on the island of Scyros.

- Throughout the narrative, Plutarch explores Theseus’s courage, strength, wisdom, and role as a benefactor and civilizer. He also touches upon his flaws, such as his impulsiveness and involvement in the abduction of women.

Life of Romulus:

- Plutarch narrates the legendary origins of Romulus and his twin brother Remus, born to Rhea Silvia, a Vestal Virgin, and supposedly the god Mars.

- He recounts their abandonment, their miraculous survival being suckled by a she-wolf, and their eventual discovery and upbringing by the shepherd Faustulus and his wife Acca Larentia.

- The biography details their youthful exploits, the conflict with Amulius (the usurper of their grandfather Numitor’s throne), and their decision to found a new city.

- Plutarch famously recounts the fratricidal dispute between Romulus and Remus over the location and naming of the city, which culminates in Romulus killing his brother and establishing Rome.

- He discusses Romulus’s actions in populating the new city, including the abduction of the Sabine women, the establishment of Roman institutions, and his military successes.

- The biography concludes with Romulus’s mysterious disappearance, with some accounts claiming he was taken up to the gods. Plutarch examines Romulus’s ambition, military prowess, and role as the founder and first king of Rome.

Comparison of Theseus and Romulus:

Following the two biographies, Plutarch provides a direct comparison of Theseus and Romulus, highlighting both their similarities and differences:

- Similarities: Plutarch notes that both were of uncertain or semi-divine parentage, possessed great strength and courage, founded major cities (Athens and Rome), resorted to the abduction of women to populate their towns, and faced domestic troubles and unpopularity towards the end of their lives. He sees them both as having a natural inclination towards leadership.

- Differences: Plutarch contrasts their motivations and methods. Theseus is portrayed as acting out of a sense of justice and a desire to rid the world of evildoers. At the same time, Romulus’s actions are often driven by necessity and ambition. Theseus’s unification of Attica is seen as more gradual and consensual than Romulus’s more forceful establishment of Rome. Plutarch also discusses the differing circumstances of their divine connections and their relationships with their families. He generally finds Theseus more virtuous in his initial actions, while acknowledging Romulus’s significant achievements in establishing Rome.

Through these biographies and their comparison, Plutarch aims to provide moral examples for his readers, exploring the complexities of leadership, virtue, and the founding of great societies. He delves into the legendary narratives, attempting to discern historical truth while also acknowledging the power and influence of myth in shaping the identities of these iconic figures and their respective cities.

Plutarch: Theseus and Romulus Compared. Table

Okay, here is a comparison of Theseus and Romulus based on Plutarch’s comparative essay (Synkrisis) presented in a table format:

| Feature | Theseus (Athens) | Romulus (Rome) | Plutarch’s Comparative Notes |

| Origins & Motivation | Royal/Divine (Aegeus/Poseidon); Chose heroism voluntarily. | Divine (Mars?); Acted out of necessity (escape servitude/danger) initially. | Theseus’s voluntary choice for great deeds is seen as initially nobler; Romulus’s rise from humble beginnings (slave/swineherd repute) is deemed more remarkable. |

| City Founding | Unified existing Attic towns (synoecism). | Founded a new city from scratch, attracting outsiders/fugitives. | Romulus’s act of creation is considered greater; Theseus built upon existing structures. |

| Violence Towards Women | Multiple abductions (Ariadne, Antiope, Helen); Motivated by personal desire/wantonness (esp. later). Led to conflict. | Mass abduction (“Rape”) of Sabine women; Motivated by state necessity (lack of wives). Led to integration. | Plutarch judges Theseus’s motives (esp. for Helen) more harshly; views Romulus’s act as necessary for the state & ultimately beneficial in outcome (uniting peoples). |

| Violence Towards Kin | Indirect cause of father Aegeus’s death (negligence); Accused regarding cousins (Pallantides). | Directly killed brother Remus in a political dispute. | Both were stained, but Plutarch analyzes intent: Romulus’s act was deliberate and political, while Theseus’s case involved negligence, passion, and misfortune. Notes: Romulus saved the mother and grandfather. |

| Leadership Style/Flaws | Leaned towards popularity/democracy; Could be rash, inconsistent, prone to anger/lust. | Became autocratic/tyrannical later; Prone to anger, potentially suspicious. | Both deviated from ideal kingship, falling into opposite extremes (demagoguery vs. despotism). |

| Relationship with Gods | Born against Oracle’s warning to Aegeus? Less direct divine favour is shown. | Miraculously saved at birth (wolf); Claimed divine parentage (Mars); Achieved apotheosis (Quirinus)? | Romulus appears more favoured/preserved by the gods throughout his story. |

| End of Life | Lost favour, exiled by citizens, killed treacherously on Scyros. | Disappeared mysteriously during a storm; possible assassination by senators. | Both faced opposition from citizens and met violent/unfitting ends away from the peak of power. |

Plutarch: Lycurgus and Numa Pompilius

Lycurgus Pictures

Numa Pompilius Pictures

Lycurgus and Numa Pompilius YouTube Video

The Lawgiver of Sparta | Lycurgus | Ancient Greece …

Numa Pompilius: The Zealot King of Rome (Roman Kings)

Plutarch: Life of Lycurgus and Life of Numa Pompilius

Plutarch’s Life of Lycurgus and Life of Numa Pompilius form another fascinating pairing in his Parallel Lives. Here, he examines two figures credited with establishing their respective states’ fundamental laws and customs: Lycurgus for Sparta and Numa Pompilius for Rome. While both aimed to create stable and virtuous societies, their approaches and the societies they shaped differed significantly.

Life of Lycurgus:

- Plutarch portrays Lycurgus as the legendary lawgiver of Sparta, who transformed a state teetering on the brink of chaos into a disciplined and formidable military power.

- He recounts Lycurgus’s travels and his consultation with the Delphic oracle, which sanctioned his laws. Plutarch details the core tenets of the Lycurgan system, including the establishment of the Gerousia (council of elders), the Ephorate (board of overseers), and the unique Spartan education system (agoge).

- The biography emphasizes the radical social and economic reforms attributed to Lycurgus: the redistribution of land, the communal mess halls (syssitia), the discouragement of wealth and luxury, and the focus on military training and physical prowess.

- Plutarch explores the austere and rigorous lifestyle imposed by Lycurgus, highlighting the emphasis on obedience, endurance, and the suppression of individual desires for the sake of the state.

- He discusses Spartan women’s unique role and status within this system, noting their physical training and relative freedom compared to women in other Greek city-states.

- Plutarch touches upon the mysterious circumstances of Lycurgus’s death, suggesting he deliberately ended his life after securing a Spartan oath to uphold his laws.

Life of Numa Pompilius:

- Plutarch presents Numa as the second king of Rome, succeeding the more martial Romulus. Numa is depicted as a wise and pious ruler credited with establishing Rome’s religious and legal foundations.

- The biography emphasizes Numa’s Sabine origins, his reputation for justice, and his reverence for the divine. Plutarch recounts his supposed consultations with the nymph Egeria, from whom he received divine guidance in establishing Roman institutions.

- Plutarch details the religious innovations attributed to Numa: the creation of priesthoods (including the Vestal Virgins, the Salii, and the Pontifex Maximus), the establishment of sacred rites and rituals, and regulating the calendar.

- He highlights Numa’s efforts to instill piety, order, and peace among the early Romans, diverting their focus from constant warfare towards religious observance and agricultural pursuits.

- Plutarch discusses Numa’s role in developing Roman law and social structures, including organizing the people into guilds based on their trades.

- The biography concludes with Numa’s peaceful reign and eventual death, leaving behind a legacy of religious tradition and a more civil Roman society.

Comparison of Lycurgus and Numa:

In his comparison, Plutarch explores the contrasting approaches and outcomes of Lycurgus’s and Numa’s lawgiving:

- Similarities: Plutarch notes that both men were credited with establishing the fundamental institutions of their states and were seen as having a connection to the divine in their lawgiving. Both aimed to foster virtue and stability within their societies.

- Differences: The core difference lies in their focus. Lycurgus shaped Sparta into a highly militaristic state, prioritizing discipline, austerity, and communal living. Numa, on the other hand, transformed early Rome by emphasizing religion, law, and peaceful coexistence. Lycurgus’s laws were designed for war and maintaining a rigid social order, while Numa’s aimed at fostering piety and civic harmony.

- Plutarch also contrasts their methods. Lycurgus implemented radical and often austere reforms that fundamentally altered Spartan society. Numa’s approach was more gradual and focused on introducing religious customs and legal frameworks.

- Plutarch reflects on the longevity of their systems. Lycurgus’s laws were remarkably enduring, shaping Sparta for centuries. Numa’s peaceful order, while influential, was eventually superseded by Rome’s expansionist and military ambitions.

- Ultimately, Plutarch seems to suggest that both lawgivers were effective in their own contexts, addressing their respective peoples’ specific needs and temperaments. Lycurgus forged a powerful military state, while Numa laid the groundwork for Rome’s religious and legal identity.

Through these biographies, Plutarch provides insights into different models of state-building and the role of the lawgiver in shaping a nation’s character and destiny. He invites readers to consider the virtues and limitations of each approach, prompting reflection on the ideal balance between order, piety, and military strength in a well-functioning society.

Plutarch: Lycurgus and Numa Pompilius Compared. Table

Okay, here is a table-formatted comparison of Lycurgus and Numa Pompilius based on Plutarch’s comparative essay (Synkrisis).

| Feature | Lycurgus (Sparta) | Numa Pompilius (Rome) | Plutarch’s Comparative Notes |

| Primary Goal/Focus | Military discipline, Equality, Stability, Obedience | Peace, Piety, Justice, Civic Order | Both aimed to shape their societies through laws derived from divine sources. |

| Method of Reform | Radical social engineering, Compulsion, Travel, Oath | Persuasion, Religious Authority (Nymph Egeria), Gradual Reform | Lycurgus’s task is seen as harder (persuading to give up luxury/wealth vs. Numa persuading warriors to be peaceful/pious). |

| Key Virtue Emphasized | Courage / Fortitude, Obedience | Justice, Piety / Religious Reverence | Plutarch weighs the value of military strength vs. justice/piety as foundational virtues. |

| Stance on Warfare | Created a highly effective military state | Promoted peace (closed Temple of Janus), discouraged war | Lycurgus made Sparta warlike to prevent injustice; Numa stopped war to prevent injustice. |

| Economic Policy | Radical equality: Land redistribution, banned gold/silver, and iron currency | Allowed wealth diversity, instituted craft guilds | Lycurgus eliminated wealth disparity; Numa only curbed military rapacity, allowing wealth accumulation. |

| Education System | State-controlled military training (agoge) for all male citizens | Left largely to parents, focused on religious rites | Plutarch strongly praises Lycurgus’s system for instilling laws; he criticizes Numa’s lack of state education as a key weakness. |

| Approach to Women/Family | Physical training for women, state interest in procreation, and unique marriage customs | Emphasized modesty, domesticity, and religious roles (Vestals) | Some poets saw Lycurgus’s system as unfeminine; Numa’s was more conducive to traditional female decorum. |

| Attitude Towards the Lower Class | Harsh treatment of Helots (criticized by Plutarch) | Relative kindness to slaves (Saturnalia custom mentioned) | Numa was considered more “Hellenic” (humane) in this aspect. |

| Personal Trajectory | Resigned kingship, self-exiled, died abroad (possibly suicide) | Accepted kingship as a private citizen, long, peaceful reign, and died naturally | Contrasts Lycurgus giving up power vs. Numa accepting it; Lycurgus choosing justice over the crown vs. Numa chosen for justice. |

| System’s Permanence | Laws endured long after his death (due to education) | Peace ended immediately after his death (lacked educational enforcement) | Sparta declined when abandoning Lycurgus’s laws; Rome grew through war after Numa’s era. |

Plutarch: Solon and Publicola

Solon Pictures

Publicola Pictures

Solon and Publicola YouTube Video

Solon of Athens: The Grandfather of Democracy

The Life of Poplicola by Plutarch

Plutarch: Life of Solon and Life of Publicola

Plutarch’s Life of Solon and Life of Publicola offer a study in the evolution of republican governance in Athens and Rome, respectively. Solon, a wise Athenian statesman, is credited with significant legal and social reforms that laid the groundwork for Athenian democracy. Publicola, a key figure in the early Roman Republic, played a crucial role in establishing its institutions after the expulsion of the monarchy.

Life of Solon:

- Plutarch portrays Solon as a man of noble birth and wisdom who was chosen as archon (chief magistrate) in a time of great social and economic turmoil in Athens.

- He details the dire situation in Athens, marked by debt slavery, land concentration, and deep class divisions between the wealthy elite and the impoverished masses.

- The biography focuses on Solon’s sweeping reforms, known as the Seisachtheia (“shaking off of burdens”), which included the cancellation of debts, the freeing of those enslaved for debt, and the prohibition of future debt slavery.

- Plutarch describes Solon’s constitutional reforms, such as the creation of new social classes based on wealth (rather than birth), the establishment of the Boule (Council of 400, later 500), and the granting of political rights to a wider segment of the citizenry, including the right to appeal judicial decisions to the Heliaia (popular assembly).

- He recounts Solon’s laws on various aspects of Athenian life, including commerce, family, and crime, emphasizing his aim to create a more just and balanced society.

- Plutarch also discusses Solon’s famous travels after his archonship, during which he visited Egypt and Lydia and famously advised King Croesus.

- The biography concludes with Solon’s return to Athens and his observations on the subsequent political struggles and the rise of tyranny, highlighting his belief in the importance of good laws and civic virtue.

Life of Publicola:

- Plutarch introduces Publius Valerius Publicola as a prominent Roman aristocrat who played a leading role in the expulsion of the tyrannical King Tarquin the Proud and the establishment of the Roman Republic.

- He emphasizes Publicola’s commitment to liberty and his efforts to ensure that the new republic did not resemble the oppressive monarchy it had overthrown.

- The biography details Publicola’s co-consulship with Lucius Junius Brutus and the measures they took to secure the republic, including the swearing of an oath never to allow another king in Rome.

- Plutarch recounts the various laws and customs attributed to Publicola aimed at safeguarding republican principles, such as allowing appeals to the people in capital cases, lowering the fasces (symbols of authority) when addressing the assembly, and building his house on the lower part of the Caelian Hill to demonstrate his commitment to equality.

- He highlights Publicola’s military successes in defending the young republic against Etruscan threats and his reputation for fairness and popularity among the Roman people.

- Plutarch discusses Publicola’s repeated consulships and his consistent dedication to upholding the laws and institutions of the republic, earning him the honorific “Publicola,” meaning “friend of the people.”

- The biography concludes with Publicola’s death and the high esteem in which he was held by the Roman citizenry as a founder and protector of their liberty.

Comparison of Solon and Publicola:

In his comparison, Plutarch draws parallels between the challenges faced by Solon and Publicola and their respective contributions to establishing more equitable forms of government:

- Similarities: Plutarch notes that both men emerged during periods of significant political and social unrest in their respective cities and were instrumental in laying the foundations for more popular forms of government. Both were known for their wisdom, integrity, and dedication to the welfare of their people. They both enacted laws aimed at preventing tyranny and protecting the rights of citizens.

- Differences: Solon’s work focused on reforming an existing aristocratic system and alleviating social and economic inequalities, paving the way for democracy. Publicola’s efforts centered on establishing a republic after the overthrow of a monarchy, ensuring that the new system was grounded in the principles of liberty and the rule of law.

- Plutarch also highlights the different contexts in which they operated. Solon dealt with internal strife and the need for fundamental social and economic adjustments. Publicola faced the immediate challenge of consolidating a newly formed republic and defending it against external enemies.

- While Solon’s reforms laid the groundwork for Athenian democracy, it was a process that continued after his time and experienced periods of instability. Publicola’s actions were more directly aimed at preventing a return to monarchy and establishing key republican institutions that proved more enduring in the early Roman Republic.

- Ultimately, Plutarch presents both Solon and Publicola as virtuous leaders who, through their wisdom and commitment to the public good, played crucial roles in shaping the political trajectories of their respective city-states, moving them towards more participatory forms of governance. He underscores the importance of good laws and the dedication of virtuous citizens in establishing and maintaining free societies.

Plutarch: Solon and Publicola Compared. Table

Okay, here is a comparison of Solon and Publicola (Publius Valerius Poplicola) based on Plutarch’s comparative essay (Synkrisis) presented in a table format.

| Feature | Solon (Athens) | Publicola (Rome) | Plutarch’s Comparative Notes |

| Context of Action | City nears collapse due to severe internal economic/social crisis (debt bondage). | Establishment and defense of a new Republic after overthrowing the monarchy (Tarquins). | Solon faced a deeper internal crisis; Publicola secured a newly formed state against external/internal threats to the monarchy. |

| Role/Primary Achievement | Foundational Lawgiver, Mediator, Poet, Sage. | Co-founder of Republic, Consul, General, Lawgiver. | Solon created a new constitution from chaos; Publicola secured and institutionalized the Republic. |

| Originality vs. Imitation | Seen as original, creating his own system (“followed no man’s example”). | Admired and imitated Solon, transferring some Athenian laws (popular election, appeal) to Rome. | Plutarch explicitly notes this unique relationship: Publicola the imitator, Solon the model. |

| Key Reforms/Laws | Seisachtheia (debt relief), Constitutional reforms (classes, Council), new law code. | Laws strengthening the Republic: Right of appeal (provocatio), severe anti-tyranny laws, established quaestors, and augmented Senate. | Solon’s debt relief is seen as unique and vital for liberty. Publicola’s laws focused on securing popular rights post-monarchy. |

| Relationship with People/Power | Acted as mediator, resisted extremes (didn’t seize tyranny when offered). | Actively courted popular favor (name “Publicola”), lowered fasces in deference, and had a strong anti-tyranny stance. | Publicola is seen as more intensely anti-tyrannical and more overtly deferential to the people. |

| Integrity/Attitude to Wealth | He resisted enriching himself during reforms and valued virtue over wealth. | Incorruptible, famously died poor and was buried at public expense, and spent his wealth beneficently. | Both are praised for their high integrity. Publicola’s honorable poverty is perhaps more emphasized as a contrast to potential consular riches. |

| Military Role | Limited (Salamis campaign, achieved via ‘counterfeit madness’ per Plutarch). | Significant; key military leader in defending the early Republic against Tarquins/allies. | Publicola clearly had the more substantial and conventional military career. |

| Later Life / End of Career | Left Athens for 10 years; lived to see his system challenged by tyranny (Pisistratus). | Remained active in politics/military; died highly honored while still influential. | Publicola’s end seen as happier and more successful in establishing his polity firmly during his lifetime. |

| Plutarch’s View on Success | The wisest of men provided foundational laws but saw them falter. | Happiest of men (fulfilling Solon’s criteria to Croesus); successfully established and defended his system until death. | Plutarch admires Solon’s wisdom deeply but awards Publicola greater success and fortune in the outcome of his life and work. |

Plutarch: Themistocles and Camillus

Themistocles Pictures

Camillus Pictures

Themistocles and Camillus YouTube Video

The Sin Of Pride | Themistocles & The Battle of Salamis …

The Life of Camillus by Plutarch

Plutarch: Life of Themistocles and Life of Camillus

Plutarch’s Life of Themistocles and Life of Camillus present a compelling study of leadership during critical periods of war and political upheaval in Greece and Rome, respectively. Themistocles, the brilliant Athenian strategist, guided Athens through the Persian Wars, while Camillus, the “second founder of Rome,” led the city through periods of defeat and rebuilding.

Life of Themistocles:

- Plutarch portrays Themistocles as an ambitious and cunning Athenian statesman and general who rose to prominence by recognizing the existential threat posed by the Persian Empire.

- He highlights Themistocles’s foresight in advocating the development of the Athenian navy, famously interpreting the Delphic oracle’s prophecy of “wooden walls” as referring to ships.

- The biography vividly recounts Themistocles’s crucial role in the Battle of Salamis (480 BCE), where his strategic brilliance and skillful maneuvering of the Athenian fleet led to a decisive Greek victory against the larger Persian navy, arguably saving Greece from Persian domination.

- Plutarch details Themistocles’s post-war efforts to rebuild Athens, including the construction of the Long Walls connecting the city to its port at Piraeus, a strategic move that ensured Athens’s long-term security and economic power.

- He also discusses Themistocles’s political maneuvering, his rivalry with other prominent Athenians, and his eventual ostracism from Athens.

- The biography follows Themistocles’s exile and his unexpected refuge with the Persian king Artaxerxes, who, despite their past conflict, welcomed him. Plutarch explores the complexities of Themistocles’s character, highlighting his ambition, intelligence, and ultimately tragic end in Persian service.

Life of Camillus:

- Plutarch presents Marcus Furius Camillus as a Roman patrician and military leader who played a pivotal role in the survival and resurgence of Rome during the 4th century BCE.

- He recounts Camillus’s early military successes, including the capture of the Etruscan city of Veii after a long siege, a significant expansion of Roman power.

- The biography details the devastating Gallic sack of Rome (circa 390 BCE) and Camillus’s absence due to alleged unjust accusations and exile.

- Plutarch dramatically narrates Camillus’s return to Rome as dictator to rally the demoralized citizens and lead the defense against the remaining Gauls. He is credited with decisively defeating the Gauls and preventing the abandonment of Rome.

- Camillus is portrayed as a figure of immense authority and integrity, earning the title of “second founder of Rome” for his role in its salvation and rebuilding.

- Plutarch discusses Camillus’s subsequent military campaigns, his wisdom in handling internal disputes, and his efforts to restore order and stability to the Roman state.

- The biography concludes with Camillus’s death, emphasizing his significant contributions to Rome’s military strength and its survival during a critical period.

Comparison of Themistocles and Camillus:

In his comparison, Plutarch examines the parallels between the challenges faced by Themistocles and Camillus and their leadership in times of crisis:

- Similarities: Plutarch notes that both men rose to prominence during periods of grave danger for their respective cities, facing formidable external enemies (Persians and Gauls). Both demonstrated exceptional military leadership and strategic thinking, playing decisive roles in turning the tide of war. Both also experienced periods of exile or political opposition within their own societies, highlighting the often precarious nature of political success.

- Differences: The nature of the threats they faced differed. Themistocles confronted a vast and technologically superior invading force, requiring naval innovation and strategic deception. Camillus dealt with a more localized, albeit devastating, invasion and the subsequent challenge of rebuilding a shattered city.

- Themistocles’s brilliance lay primarily in naval strategy and political maneuvering, while Camillus excelled in traditional Roman land warfare and possessed a strong sense of Roman tradition and authority.

- Plutarch also contrasts their post-crisis actions. Themistocles focused on long-term strategic development (the Long Walls), while Camillus concentrated on immediate recovery and the restoration of Roman institutions and morale.

- The circumstances of their exiles also differ significantly, with Themistocles ultimately seeking refuge with a former enemy, while Camillus was recalled by his own people in their direst hour.

- Ultimately, Plutarch presents both Themistocles and Camillus as indispensable leaders who, through their courage, intelligence, and dedication, guided their cities through existential crises. Themistocles’s foresight saved Athens and shaped its naval power, while Camillus’s resilience and leadership ensured Rome’s survival and resurgence, solidifying his place as a pivotal figure in its early history.

Plutarch: Themistocles and Camillus Compared

Okay, here is a comparison of Themistocles and Camillus based on Plutarch’s comparative essay (Synkrisis) presented in a table format.

| Feature | Themistocles (Athens) | Camillus (Rome) | Plutarch’s Comparative Notes |

| Primary Achievement | Defeating the Persian invasion at the Battle of Salamis (saving Greece). | Numerous victories: Conquering Veii, Saving Rome from Gauls (“Second Founder”). | Themistocles’ achievement is perhaps greater in singular impact/genius; Camillus’s is more numerous over a longer career. |

| Character / Key Talent | Natural genius, foresight, political shrewdness, cunning, adaptability. | Military skill, discipline, piety, traditional Roman virtue, leadership. | Themistocles’ talent is seen as more innate/brilliant; Camillus’s, perhaps, is derived more from experience/effort, embodying Roman ideals more straightforwardly. |

| Political Context | Operated within the Athenian Democracy; it often used popular support. | Operated within the Roman Republic; often held dictatorial power during crises. | Different systems influenced their paths to power and methods of leadership. |

| Experience with Exile | Ostracized due to political envy, arrogance, and suspicion of Medism. | Exiled over a dispute regarding the spoils of Veii, for perceived arrogance. | Both saved their cities yet faced ingratitude and political opposition, leading to exile. |

| Conduct During Exile | Eventually sought refuge and entered the service of the Persian King (enemy of Greece). | Lived quietly until recalled; returned immediately to save Rome from the Gauls. | Plutarch strongly contrasts their actions, heavily favoring Camillus’s patriotism and refusal to harm Rome, while implicitly condemning Themistocles’ choice. |

| End of Life / Legacy | Died in honorable exile in Persia, unable to return to Athens. Complex legacy. | Recalled to further glory, died old and highly honored in Rome. Clear heroic legacy. | Plutarch views Camillus’s end as far more fortunate and honorable. |

| Overall Judgment Point | Possessed unparalleled genius but flawed consistency/choices, especially in exile. | Showed consistent virtue, patriotism, and military success; ending more commendable. | While admiring Themistocles’ brilliance, Plutarch ultimately favors Camillus for his steadfast virtue and honorable relationship with his country. |

Plutarch: Pericles and Fabius Maximus

Pericles Pictures

Fabius Maximus Pictures

Pericles and Fabius Maximus YouTube Video

Pericles, the Golden Age of Athens

The Life of Fabius Maximus by Plutarch

The Horrifying Way Rome Dealt With Wartime Loss

Plutarch: Life of Pericles and Life of Fabius Maximus

Plutarch’s Life of Pericles and Life of Fabius Maximus offer a fascinating study in leadership styles during times of war and political tension. Pericles, the preeminent Athenian statesman during its Golden Age, guided Athens through a period of cultural flourishing and the early stages of the Peloponnesian War. Fabius Maximus, on the other hand, was a Roman leader known for his cautious and strategic approach during the Second Punic War against Hannibal.

Life of Pericles:

- Plutarch portrays Pericles as a man of noble birth, exceptional eloquence, and profound political acumen who dominated Athenian politics for over four decades.

- He highlights Pericles’s early political skills, his association with popular reforms, and his ability to sway the Athenian assembly through his powerful oratory.

- The biography details Pericles’s role in the construction of magnificent public works on the Acropolis, such as the Parthenon, which beautified Athens and provided employment, marking the zenith of Athenian cultural achievement.

- Plutarch discusses Pericles’s leadership during the lead-up to the Peloponnesian War, emphasizing his strategic thinking and his unwavering belief in Athens’s strength and its democratic principles.

- He recounts the initial phases of the war, including Pericles’s defensive strategy of retreating within the city walls and relying on Athens’s naval power, a strategy that, while initially sound, ultimately contributed to the devastating plague.

- Plutarch explores the challenges Pericles faced, including political opposition, personal tragedies (like the loss of his sons), and the shifting public opinion during the war.

- The biography concludes with Pericles’s death during the plague, acknowledging his immense influence on Athens and the complexities of his legacy, including both the brilliance of his leadership and the criticisms leveled against him.

Life of Fabius Maximus:

- Plutarch presents Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus as a Roman statesman and general who rose to prominence during the critical Second Punic War against Hannibal.

- He emphasizes Fabius’s cautious and deliberate approach to warfare, earning him the cognomen “Cunctator” (the Delayer) for his strategy of avoiding direct confrontation with Hannibal’s superior forces.

- The biography details Fabius’s strategy of attrition: shadowing Hannibal’s army, harassing his supply lines, and wearing him down without engaging in a major battle. This unconventional approach was met with criticism and impatience by some in Rome.

- Plutarch recounts the political challenges Fabius faced, including accusations of cowardice and the temporary appointment of a master of the horse, Marcus Minucius Rufus, who advocated for a more aggressive strategy, leading to a near-disastrous Roman defeat.

- He highlights Fabius’s wisdom and steadfastness in adhering to his strategy despite public pressure, ultimately recognizing that Hannibal’s strength lay in open battle.

- Plutarch discusses Fabius’s later contributions to Rome, including his role in maintaining stability and offering wise counsel during the prolonged war.

- The biography concludes with Fabius’s death, honoring him as a figure whose patience and strategic thinking were crucial to Rome’s eventual victory over Hannibal, even though he did not live to see the final triumph.

Comparison of Pericles and Fabius Maximus:

In his comparison, Plutarch examines two contrasting leadership styles in times of conflict and political complexity:

- Similarities: Plutarch notes that both Pericles and Fabius Maximus were highly respected figures in their respective societies, known for their wisdom and commitment to their states’ welfare. Both faced significant challenges and opposition during their leadership. Both also demonstrated a long-term perspective in their strategies, though applied in different ways.

- Differences: The most striking difference lies in their leadership styles. Pericles was a dynamic orator and a proponent of bold initiatives, leading Athens to its cultural zenith and confidently entering the Peloponnesian War. Fabius was cautious and deliberate, employing a strategy of attrition and delay to counter a seemingly invincible enemy.

- Pericles’s power stemmed from his eloquence and his ability to persuade the Athenian assembly, operating within a democratic system. Fabius’s authority derived from his senatorial standing, his reputation for wisdom, and his steadfastness in the face of public criticism within a more aristocratic republic.

- The nature of the conflicts they faced also differed. Pericles led Athens in a protracted war against another major Greek power, while Fabius confronted a foreign invader who had inflicted devastating defeats on Roman armies.

- Plutarch seems to suggest that both leadership styles had their merits and were suited to their specific circumstances. Pericles’s bold vision guided Athens to its Golden Age, but his war strategy had limitations. Fabius’s cautious approach, while initially unpopular, ultimately proved crucial to Rome’s survival against Hannibal’s brilliance.

Through these biographies, Plutarch explores the multifaceted nature of leadership, demonstrating that effective governance can take different forms depending on the context, the leader’s character, and the state’s needs. He invites readers to consider the virtues of decisive action and prudent restraint in navigating times of crisis.

Plutarch: Pericles and Fabius Maximus Compared. Table

Please Note: The formal comparison essay (Synkrisis) by Plutarch, which usually follows the paired biographies, is lost for the pair of Pericles and Fabius Maximus. Therefore, the comparison points below are inferred from the themes and parallels Plutarch presents in their individual Lives, reflecting why he likely chose to pair these two particular statesmen.

Here is a table outlining the likely points of comparison between Pericles and Fabius Maximus based on Plutarch’s implied parallels:

| Feature | Pericles (Athens) | Fabius Maximus (Rome) | Implied Comparison Points by Plutarch |

| Shared Core Virtues | Gravity, dignity, intelligence, steadfastness, incorruptibility, resisted popular passions. | Gravity, dignity, intelligence, steadfastness, incorruptibility, resisted popular passions. | Plutarch paired them primarily for these shared qualities of calm, rational, and resolute leadership, especially in difficult times. |

| Primary Role / Context | Leading statesman & general during Athens’ Golden Age; managed empire & democracy. | Roman general & dictator (“Cunctator”); led Rome during its most perilous period against Hannibal. | Both were paramount leaders of their states during major existential wars (Peloponnesian War start / Second Punic War crisis). |

| Major Challenge Faced | Leading a confident, powerful state into a long war; managing internal politics & plague. | Saving a state facing imminent destruction after catastrophic defeats by a foreign invader (Hannibal). | Fabius faced a more immediate, desperate crisis requiring extraordinary measures to ensure state survival. |

| Military Strategy | Defensive: rely on walls/navy, avoid decisive land battles, preserve strength. | Defensive: Avoid pitched battles (“Fabian tactics”), harass the enemy, target supplies, wear down the opponent through attrition. | Both adopted cautious, strategically sound (though unpopular) defensive strategies tailored to their specific circumstances, prioritizing state preservation over risky glory. |

| Relationship w/ People / Criticism | Faced criticism for letting Attica be ravaged; maintained control through oratory/authority. | Faced intense criticism & accusations of cowardice for delaying tactics; endured political opposition (e.g., Minucius). | Both showed immense fortitude in adhering to unpopular but necessary strategies despite significant public and political pressure. Fabius’s situation perhaps required greater resilience against direct accusations of cowardice. |

| Political Style / Influence | Dominated Athenian democracy through persuasive oratory and long-held authority (“Olympian”). | Influential through gravitas, experience, traditional authority; repeatedly appointed dictator in crises. | Pericles led through democratic persuasion; Fabius through established authority and reputation for prudence. |

| Integrity / Motivation | Seen as incorruptible despite managing vast public funds; motivated by Athens’ glory/welfare. | Praised for integrity and lack of personal enrichment; endured slights for the state’s good; motivated by patriotism. | Both presented as prioritizing the state’s well-being above personal gain or easy popularity. |

| Cultural Association | Presided over and fostered Athens’ cultural peak (Parthenon, arts, philosophy). | Primarily focused on military salvation and traditional Roman virtues; less associated with cultural patronage. | Pericles’ leadership encompassed broader cultural dimensions characteristic of Athens’ Golden Age. |

| Plutarch’s Likely View | Admired as an exemplary rational leader and architect of Athenian greatness. | Deeply admired as the steadfast savior of Rome, whose prudent strategy and fortitude were essential. | Plutarch likely saw both as models of wise, steadfast leadership, perhaps highlighting Fabius’s extraordinary resilience and prudence in the face of near-certain doom. |

Plutarch: Alcibiades and Coriolanus

Alcibiades Pictures

Coriolanus Pictures

Alcibiades and Coriolanus YouTube Video

Alcibiades, the Peloponnesian War, and the Art of Intrigue

The Life of Cauis Marcius Coriolanus by Plutarch

Plutarch: Life of Alcibiades and Life of Coriolanus

Plutarch’s Life of Alcibiades and Life of Coriolanus offer a compelling study of brilliant but ultimately flawed individuals whose exceptional talents were intertwined with significant character weaknesses, leading to dramatic and often tragic consequences for their respective city-states. Alcibiades, the charismatic and controversial Athenian, and Coriolanus, the fiercely proud Roman patrician, both possessed extraordinary abilities but struggled with hubris and an inability to navigate the complexities of their political environments.

Life of Alcibiades:

- Plutarch portrays Alcibiades as a man of immense talent, striking beauty, and captivating charm, but also as impulsive, ambitious, and prone to betrayal.

- He highlights Alcibiades’s privileged upbringing, his association with Socrates, and his early successes in Athenian politics and military command.

- The biography details Alcibiades’s instrumental role in the disastrous Sicilian Expedition, his subsequent betrayal of Athens by defecting to Sparta, and his later return to Athens in triumph.

- Plutarch recounts Alcibiades’s military achievements while serving both Sparta and Athens, showcasing his strategic brilliance and his ability to adapt to different political landscapes.

- However, the biography also emphasizes Alcibiades’s recklessness, his scandalous behavior, and the deep distrust he engendered among his fellow citizens, ultimately leading to his final exile and assassination.

- Plutarch explores the complexities of Alcibiades’s character, acknowledging his undeniable genius and his contributions to Athens, while also condemning his lack of loyalty and his self-serving actions.

Life of Coriolanus:

- Plutarch presents Caius Marcius Coriolanus as a man of exceptional courage, military prowess, and unwavering integrity, but also as fiercely proud, inflexible, and contemptuous of the common people.

- He recounts Coriolanus’s early military valor, particularly during the siege of Corioli (hence his name), where his bravery earned him great renown.

- The biography details Coriolanus’s political career in Rome, marked by his aristocratic disdain for the plebeians and his opposition to granting them greater political rights (specifically, the tribuneship).

- Plutarch describes Coriolanus’s uncompromising stance during a grain shortage, demanding the abolition of the tribunes in exchange for distributing grain, which led to his banishment from Rome.

- The biography dramatically narrates Coriolanus’s alliance with Rome’s enemies, the Volscians, and his leading their army against his own city, bringing Rome to the brink of destruction.

- Plutarch recounts the emotional pleas of Coriolanus’s mother, Volumnia, and his wife, which ultimately persuaded him to withdraw his forces, thus saving Rome but leading to his own death at the hands of the Volscians.

- Plutarch emphasizes Coriolanus’s rigid adherence to his principles and his inability to compromise, highlighting the tragic consequences of his unyielding pride.

Comparison of Alcibiades and Coriolanus:

In his comparison, Plutarch examines the parallel trajectories of two brilliant but deeply flawed individuals whose character flaws led to their downfall and significantly impacted their states:

- Similarities: Plutarch notes that both Alcibiades and Coriolanus possessed extraordinary talents and achieved great military success. Both were also marked by a significant degree of arrogance and an inability to connect with or understand the common people in their societies. Their inflexibility and pride ultimately led to their alienation from their own cities and their involvement with their enemies.

- Differences: Alcibiades’s flaws were characterized by a lack of consistent loyalty and a self-serving ambition that led him to betray Athens multiple times. Coriolanus’s primary failing was his unyielding pride and his contempt for the plebeians, which drove him to seek revenge against Rome. Alcibiades was adaptable and could charm his way into different situations, while Coriolanus was rigid and uncompromising.

- Alcibiades’s impact on Athens was more fluid and dynamic, marked by periods of great success and deep betrayal. Coriolanus’s impact was more direct and dramatic, bringing Rome to the verge of destruction due to his vengeful actions.

- Plutarch seems to suggest that while both men were exceptionally gifted, their inability to control their inherent flaws and to navigate the complexities of their political environments ultimately led to tragedy for themselves and significant turmoil for their respective cities. Alcibiades’s lack of principle and Coriolanus’s excessive pride serve as cautionary tales of how even great talents can be undermined by character weaknesses.

Through these biographies, Plutarch explores the intricate relationship between talent, character, and political success, highlighting the dangers of unchecked ambition and unyielding pride in the public sphere. He invites readers to reflect on the importance of virtue and the ability to compromise in effective leadership and responsible citizenship.

Plutarch: Alcibiades and Coriolanus Compared. Table

Okay, here is a comparison of Alcibiades and Coriolanus based on Plutarch’s comparative essay (Synkrisis) presented in a table format.

| Feature | Alcibiades (Athens) | Coriolanus (Rome) | Plutarch’s Comparative Notes |

| Core Similarity | Great ability (military/political); flawed character led to harming homeland after feeling wronged. | Great ability (military); flawed character led to harming homeland after feeling wronged. | Both exemplify how personal failings in great men can lead to betrayal and immense damage to their own countries. Both caused great calamities for their cities. |

| Defining Character Flaw | Inconsistency, excessive ambition, lack of stable principle, vanity, perhaps dissoluteness. | Overwhelming aristocratic pride (superbia), inflexibility, uncontrolled anger, contempt for common people. | Contrasts Alcibiades’ adaptable but unprincipled nature with Coriolanus’s straightforward but destructive pride and anger. |

| Motivation for Turning Against State | Self-preservation (fleeing condemnation), opportunism, ambition for power/influence wherever possible. | Rage, wounded pride, desire for revenge after perceived unjust exile inflicted by the plebeians/tribunes. | Alcibiades driven by complex self-interest; Coriolanus by a simpler (though excessive) reaction to perceived insult/injustice. |

| Nature of Harm Inflicted | Strategic advice to enemies (Sparta, Persia), promoting disastrous policies (Sicilian Expedition). | Directly led an enemy (Volscian) army to besiege Rome, threatening its destruction. | Coriolanus’s threat was more immediate and militarily direct; Alcibiades’ harm was perhaps more insidious and political, but also devastating long-term. |

| Political Style / Demeanor | Charismatic, adaptable, could manipulate popular opinion, lived extravagantly. | Openly contemptuous of plebeians, haughty, refused to court popular favor, valued aristocratic virtue. | Alcibiades could play the political game when needed; Coriolanus’s pride made him politically self-destructive among the populace. |

| Consistency / Adaptability | Highly adaptable, changed allegiances and manners multiple times (Athens, Sparta, Persia). | Rigidly consistent in his pride and principles until the very end. | Alcibiades is seen as changeable/less predictable; Coriolanus is stubbornly consistent (perhaps less deceitful in his enmity, but also less flexible). |

| Final Act / Yielding | Recalls to Athens based on political shifts/opportunity; no single act of relenting for patriotic reasons. | Spared Rome only after intense emotional appeals from his mother, wife, and Roman matrons (pietas). | Coriolanus’s yielding, though leading to his doom, showed susceptibility to family duty; Alcibiades’ shifts were more strategic/opportunistic. |

| End of Life / Legacy | Assassinated in exile in Phrygia; legacy is one of brilliant potential wasted by instability/betrayal. | Killed by resentful Volscians or died in disgraced exile; legacy is one of great valor undone by pride and treason. | Both died violently/unhappily in exile, serving as tragic warnings against letting personal flaws override patriotism. |

| Plutarch’s Overall Judgment | Condemns both for harming their countries. Views Alcibiades as brilliant but dangerously inconsistent/unprincipled. Views Coriolanus as valiant but fatally flawed by pride/anger. | Neither is presented as a model, but as examples of how character flaws can ruin great men and endanger states. |

Plutarch: Timoleon and Aemilius Paulus

Timoleon Pictures

Aemilius Paulus Pictures

Timoleon and Aemilius Paulus YouTube Video

The Life of Timoleon by Plutarch

The Life of Aemilius By Plutarch

Plutarch: Life of Timoleon and Life of Aemilius Paulus

Plutarch’s Life of Timoleon and Life of Aemilius Paulus offer a study in virtuous leadership and the ability to navigate complex military and political situations with integrity and skill. Timoleon, who liberated the Greek cities of Sicily from tyranny, is paired with Aemilius Paulus, the Roman general renowned for his victory over Macedon and his upright character. Both men were admired for their competence, their sense of justice, and their relative lack of personal ambition.

Life of Timoleon:

- Plutarch portrays Timoleon as a man of noble Corinthian lineage who reluctantly accepted the call to lead Syracuse against its tyrants. He is depicted as possessing a naturally virtuous character, marked by integrity and a disdain for personal gain.

- The biography recounts the complex political situation in Sicily, where various Greek cities were plagued by internal strife and the rule of oppressive tyrants, often with Carthaginian interference.

- Plutarch details Timoleon’s remarkable and somewhat unexpected successes in Sicily. Despite facing numerous challenges, including a small initial force and the opposition of powerful tyrants and Carthaginian armies, he achieved decisive victories. He is particularly known for his victories at the Crimissus River and Abacaenum.

- The biography emphasizes Timoleon’s skill in uniting the Greek cities of Sicily under a common cause of liberation and establishing stable, lawful governments after the expulsion of the tyrants. He is credited with bringing a period of peace and prosperity to the region.

- Plutarch highlights Timoleon’s modesty and his refusal to establish himself as a ruler in Syracuse, choosing instead to work through elected officials and uphold the laws. He maintained a relatively simple lifestyle and prioritized the well-being of the Sicilian Greeks over his own power.

- The biography concludes with Timoleon’s respected later life in Sicily, where he remained influential but out of formal power, offering wise counsel until his death. He is remembered as a liberator and a model of selfless leadership.

Life of Aemilius Paulus:

- Plutarch presents Lucius Aemilius Paulus Macedonicus as a distinguished Roman patrician known for his military prowess, his adherence to Roman virtue (virtus), and his dignified character.

- The biography recounts his initial consulship and his military successes in Hispania. However, it primarily focuses on his second consulship and his command in the Third Macedonian War against King Perseus.

- Plutarch details Aemilius Paulus’s meticulous preparations for the Macedonian campaign, his emphasis on discipline and training, and his strategic brilliance in the decisive Battle of Pydna, which brought an end to the Macedonian kingdom.

- The biography describes Aemilius Paulus’s just and organized administration of Macedonia after his victory, contrasting it with the often exploitative practices of other Roman commanders. He is portrayed as fair and respectful of the conquered people while firmly establishing Roman authority.

- Plutarch also touches upon the personal tragedies Aemilius Paulus endured, including the loss of his two eldest sons, which he bore with stoic dignity, placing the interests of the Republic above his personal grief.

- The biography concludes with Aemilius Paulus’s triumphant return to Rome and the grand triumph held in his honor, followed by his respected later life. He is remembered as a virtuous and capable leader who exemplified Roman ideals.

Comparison of Timoleon and Aemilius Paulus:

In his comparison, Plutarch highlights the shared virtues and the different contexts of leadership exhibited by Timoleon and Aemilius Paulus:

- Similarities: Plutarch emphasizes the integrity, justice, and lack of personal ambition in both men. Both were successful military commanders who earned the respect and admiration of their people. Both are presented as acting out of a sense of duty and prioritizing the common good over personal gain. They both brought stability and order to regions plagued by conflict.

- Differences: Timoleon operated in a context of fragmented Greek city-states threatened by tyranny and external powers, acting as a liberator and unifier. Aemilius Paulus led the well-established Roman Republic in a war of conquest against a powerful kingdom. Timoleon’s successes often involved overcoming significant odds with limited resources, while Aemilius Paulus commanded the might of Rome.

- Timoleon’s primary achievement was the liberation and organization of independent Greek cities, while Aemilius Paulus’s was the decisive conquest and subsequent administration of a former kingdom under Roman rule.

- Plutarch seems to present both men as exemplars of virtuous leadership, albeit in different arenas. Timoleon’s selflessness in liberating Sicily and establishing free governments is contrasted with Aemilius Paulus’s disciplined command and just administration following a major Roman conquest. Both demonstrate that effective leadership can be guided by integrity and a focus on the well-being of those they lead.

Through these biographies, Plutarch illustrates that virtuous leadership can manifest in different ways depending on the historical circumstances. Both Timoleon and Aemilius Paulus serve as models of leaders who achieved greatness through their competence, integrity, and dedication to the welfare of their people, rather than through personal ambition or tyranny.

Plutarch: Timoleon and Aemilius Paulus Compared. Table

Okay, here is a comparison of Timoleon and Aemilius Paulus based on Plutarch’s comparative essay (Synkrisis) presented in a table format.

| Feature | Timoleon (Greek/Corinthian) | Aemilius Paulus (Roman) | Plutarch’s Comparative Notes |

| Primary Military Achievement | Liberating Sicily from tyrants and defeating Carthaginians (esp. Battle of Crimisus). | Conquering the Kingdom of Macedon (Battle of Pydna), ending the Antigonid dynasty. | Both achieved glorious victories against powerful enemies. Plutarch weighs Timoleon achieving much with limited/disorderly forces vs. Paulus defeating an established kingdom. |

| Role | Liberator, Restorer of democracy/cities. | Conqueror, Organizer of Roman province. | Contrasts the nature of their campaigns: liberation vs. conquest. |

| Virtue vs. Fortune (Arete vs. Tyche) | Career marked by extraordinary good fortune, often seen as divinely guided. | Success attributed more to skill, discipline, and preparation; faced personal misfortune (death of sons). | Plutarch explicitly discusses this balance for both, finding Timoleon exceptionally favored by fortune, while Paulus demonstrated virtue amidst mixed personal fortune. |

| Integrity (Wealth/Power) | Lived modestly, retired voluntarily from power, accepted gifted estate (seen as acceptable). | Refused any personal share of vast Macedonian spoils, known for incorruptibility. | Both are praised for their integrity. Plutarch suggests Paulus’s refusal to accept anything represents a “surpassing virtue.” |

| Handling Personal Adversity | Deeply affected by remorse over brother’s justified death (tyranny), withdrew for years; faced blindness with fortitude. | Endured the death of two sons around his triumph with stoic dignity and continued public duty. | Plutarch greatly admires Paulus’s fortitude in grief, finding it showed a more perfectly tempered spirit than Timoleon’s prolonged, perhaps excessive, remorse. |

| Background / Character Formation | Virtue stood out compared to other corrupt Greek commanders in Sicily (seen as more innate). | Virtue seen partly as instilled by Roman laws, customs, and discipline of his time. | Both were models of virtue, but Plutarch notes the differing contexts that shaped/highlighted their integrity. |

| Death / Legacy | Died blind but highly honored and revered as a father figure by Sicilians. | Died after a distinguished career, highly respected in Rome. | Contrasts Timoleon’s honored but personally afflicted end with Paulus’s more conventional Roman end after great triumph and personal tragedy. |

| Overall Judgment Point | A remarkable figure whose virtue and astonishing good fortune achieved great liberation. | Embodied Roman discipline, skill, integrity, and exceptional fortitude in adversity. | Plutarch admires both greatly, exploring different paths to virtuous success and the interplay of character, skill, and fortune. Paulus perhaps seen as having a more perfectly balanced/stoic character. |

Plutarch: Pelopidas and Marcellus

Pelopidas Pictures

Marcellus Pictures

Pelopidas and Marcellus YouTube Video

The Life of Pelopidas By Plutarch

The Epic Life of Marcus Marcellus

Ingenious Siegecraft: The (Staggering) Siege of Syracuse 213 …

Plutarch: Life of Pelopidas and Life of Marcellus

Plutarch’s Life of Pelopidas and Life of Marcellus offer a study in military leadership and the contrasting fortunes of two prominent figures in Greek and Roman history during periods of intense conflict. Pelopidas, the Theban general and statesman, was instrumental in establishing Theban hegemony in Greece, while Marcus Claudius Marcellus was a renowned Roman general who played a key role in the Second Punic War, particularly in the siege of Syracuse. Both were celebrated for their courage and military skill, but their approaches and ultimate legacies differed.

Life of Pelopidas:

- Plutarch portrays Pelopidas as a man of noble Theban lineage, characterized by his bravery, his unwavering friendship with Epaminondas, and his dedication to the freedom and power of Thebes.

- The biography recounts Pelopidas’s early involvement in the liberation of Thebes from Spartan occupation in 379 BCE, a pivotal event that set the stage for Theban ascendancy.

- Plutarch emphasizes Pelopidas’s crucial role in the development of the Theban military, particularly the Sacred Band, an elite infantry unit composed of pairs of lovers who fought with unmatched ferocity.

- The biography details Pelopidas’s significant military victories, often in collaboration with Epaminondas, including the decisive Battle of Leuctra (371 BCE) against Sparta, which shattered Spartan power and ushered in the Theban hegemony.

- Plutarch also recounts Pelopidas’s diplomatic missions and his involvement in Thessaly, where he played a key role in opposing tyrants and Macedonian influence. He faced considerable danger in these endeavors, even being imprisoned at one point.

- The biography concludes with Pelopidas’s death in Thessaly during a battle against Alexander of Pherae. Plutarch mourns the loss of a great Theban leader who, alongside Epaminondas, had brought Thebes to its zenith.

Life of Marcellus:

- Plutarch presents Marcus Claudius Marcellus as a valiant and tenacious Roman general who distinguished himself during the Second Punic War against Hannibal. He was known for his courage in single combat and his successful sieges of fortified cities, earning him the nickname “the Sword of Rome.”

- The biography recounts Marcellus’s early military career, including his victory over the Gauls in northern Italy, for which he was awarded the spolia opima (the armor stripped from an enemy commander killed in single combat by a Roman commander).

- Plutarch details Marcellus’s crucial role in the defense of Nola against Hannibal’s forces, a significant early Roman success in the war.

- The biography extensively covers the siege of Syracuse (214-212 BCE), a major turning point in Marcellus’s career. Plutarch vividly describes the ingenious defenses devised by Archimedes, which initially thwarted the Roman efforts, and Marcellus’s eventual capture of the city.

- Plutarch also recounts the tragic circumstances of Archimedes’s death during the sack of Syracuse, despite Marcellus’s orders to spare the renowned mathematician.

- The biography discusses Marcellus’s subsequent campaigns against Hannibal in Italy, highlighting his strategic acumen and his ability to engage the Carthaginian general effectively, even if not always decisively.

- The biography concludes with Marcellus’s death in an ambush in Italy. Plutarch portrays him as a formidable Roman commander who played a vital role in Rome’s struggle against Hannibal.

Comparison of Pelopidas and Marcellus:

In his comparison, Plutarch examines two military leaders who achieved significant successes in different contexts and against different adversaries:

- Similarities: Plutarch notes the exceptional courage and military prowess of both Pelopidas and Marcellus. Both were known for their personal bravery in battle and their ability to inspire their troops. Both played crucial roles in major conflicts of their time, leading their respective states to significant victories.

- Differences: Pelopidas operated in the complex and often shifting alliances of the Greek city-states, primarily against Spartan power and various tyrants. Marcellus fought against the formidable Hannibal and the Carthaginian forces during a major external threat to Rome.

- Pelopidas’s leadership was closely intertwined with his friendship and collaboration with Epaminondas, forming a powerful Theban partnership. Marcellus operated within the Roman military and political system, often independently.

- While both were successful in siege warfare (Pelopidas in Thessaly, Marcellus at Syracuse), Marcellus’s siege of Syracuse is particularly famous due to Archimedes’s defenses.

- Pelopidas’s legacy is primarily tied to the rise and relatively short-lived dominance of Thebes in Greece. Marcellus is remembered as a key figure in Rome’s eventual victory over Hannibal, a conflict with far more lasting consequences for the Mediterranean world.

- Plutarch seems to suggest that both men were exemplary military leaders in their own right, demonstrating courage, strategic thinking, and a commitment to their states. However, the scale and long-term impact of Marcellus’s achievements within the context of the Second Punic War arguably give him a more prominent place in history.

Through these biographies, Plutarch explores the qualities of effective military leadership in different historical settings, highlighting the courage, strategic skill, and dedication required to lead armies and shape the destinies of nations in times of war.

Plutarch: Pelopidas and Marcellus Compared. Table

Okay, here is a comparison of Pelopidas and Marcellus based on Plutarch’s comparative essay (Synkrisis) presented in a table format.

| Feature | Pelopidas (Theban) | Marcellus (Roman) | Plutarch’s Comparative Notes |

| Shared Traits | Valiant, laborious, passionate, high-spirited warrior. | Valiant, laborious, passionate, high-spirited warrior (“Sword of Rome”). | Plutarch notes their natures and dispositions were remarkably similar in terms of martial virtue. |

| Key Military Achievements | Liberating Thebes (stealth/daring), victories at Tegyra & Leuctra (vs. Spartans). | Winning spolia opima (vs. Gallic king), capture of Syracuse, fighting Hannibal. | Both had glorious victories against formidable foes. Compares Pelopidas’s cunning liberation & undefeated record (as commander) vs. Marcellus’s unique spolia opima & greater number of wins. |

| Manner of Death | Died charging the tyrant Alexander of Pherae in battle, driven by righteous anger. | Died carelessly in an ambush by Hannibal’s forces during reconnaissance. | Central Point: Both died perhaps rashly. Plutarch finds Pelopidas’s death in combat against a tyrant more excusable/fitting than Marcellus’s death through lack of caution for a seasoned commander. |