John Audubon, Florence Bailey, Roger Peterson, and Phoebe Snetsinger: Birdwatchers

This list of four figures perfectly encapsulates the evolution of birding from a rough frontier science into a modern global hobby. They represent the four distinct eras of how humans have interacted with birds.

Here is how Audubon, Bailey, Peterson, and Snetsinger changed the world of birdwatching.

1. John James Audubon (1785–1851)

The Era of the Gun & The Brush

Audubon represents the romantic, rough-and-tumble origins of American birding. In the early 19th century, there were no cameras or high-quality optics. To “watch” a bird, you had to hunt it.

- The Method: “Shotgun Ornithology.” Audubon would shoot birds, wire them into dynamic, lifelike poses, and then paint them life-size.

- The Masterpiece: The Birds of America. It remains one of the most expensive and famous books in history. His paintings were not merely scientific records; they were dramatic art, often depicting violent scenes (such as hawks attacking prey) that captivated the public imagination.

- The Legacy: He didn’t just catalog birds; he gave them a personality. The National Audubon Society was named in his honor (after his death) by the generation that followed him.

2. Florence Merriam Bailey (1863–1948)

The Era of Conservation & Binoculars

If Audubon was the hunter, Bailey was the conscience. By the late 1800s, birds were being slaughtered by the millions for the millinery (hat-making) trade. Bailey led the pivot toward ethical observation.

- The Method: She championed the “opera glass” (early binoculars) over the gun. She argued that studying a bird’s behavior, song, and habitat was more scientifically valuable than measuring its dead body.

- The Masterpiece: Birds Through an Opera-Glass (1889). This is widely considered the first true field guide in the modern sense, written to help amateurs identify live birds.

- The Legacy: She was a foundational figure in the movement to stop the feather trade. She proved that birdwatching could be a gentle, observational science, opening the field to women and amateurs.

3. Roger Tory Peterson (1908–1996)

The Era of Democratization & The Guide

Before Peterson, birding was difficult. Books were organized by scientific anatomy, meaning you had to know biology to find a bird in the index. Peterson created the “user interface” for nature.

- The Method: The “Peterson Identification System.” He grouped birds by appearance, not by DNA. Most importantly, he used arrows to point to specific “field marks” (a stripe on the wing, a yellow ring on the eye) that distinguished similar species.

- The Masterpiece: A Field Guide to the Birds (1934). It sold out in a week.

- The Legacy: He made birdwatching accessible to anyone with $3 for a book and a pair of binoculars. He is the reason birding became a mass hobby in the 20th century.

4. Phoebe Snetsinger (1931–1999)

The Era of Sport & The List

Snetsinger represents the modern extreme of the hobby: “Listing.” Diagnosed with terminal melanoma in 1981 and given months to live, she chose to spend her remaining time traveling the globe. She survived for 18 more years, driven by an obsession with seeing new species.

- The Method: Competitive global travel. She didn’t just watch birds; she hunted for “lifers” (birds she hadn’t seen before).

- The Masterpiece: She became the first person in history to see 8,000 species (roughly 80% of all bird species on Earth at the time).

- The Legacy: Her memoir, Birding on Borrowed Time, documents the sheer endurance required for top-tier birding. She died in a van accident in Madagascar, effectively dying “with her boots on” while pursuing the list.

Summary of Evolution

| Figure | Role | The Tool | The Philosophy |

| Audubon | The Artist | Shotgun | “Capture the beauty.” |

| Bailey | The Protector | Opera Glass | “Save the life.” |

| Peterson | The Teacher | Field Guide | “Identify the marks.” |

| Snetsinger | The Competitor | The List | “See them all.” |

John James Audubon (1785–1851)

John James Audubon 1826

(Wiki Image By John Syme – The White House Historical Association, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9359700)

John James Audubon Quotes

John James Audubon’s writing is just like his painting: dramatic, slightly embellished, and deeply romantic. He didn’t just record data; he tried to capture the “spirit” of the living creature.

Here is a curation of his most revealing quotes, categorized by the passions that drove him.

On the Art of Observation

Audubon was a pioneer of “field ornithology”—the idea that you have to watch birds in life, not just study dead skins in a museum.

- “When the bird and the book disagree, believe the bird.” (This is perhaps his most famous maxim, summarizing his rejection of the “armchair naturalists” of Europe who had never seen the birds they wrote about.)

- “I never for a day gave up listening to the songs of our birds, or watching their peculiar habits, or delineating them in the best way I could.”

- “The worse my drawings were, the more beautiful did the originals appear.” (A reflection on his constant frustration that no paint could ever capture the true brilliance of nature’s colors.)

On the Abundance of Nature (The Passenger Pigeon)

His description of the Passenger Pigeon migration in 1813 is his most famous work. It captures a scale of nature that no longer exists.

- “The air was literally filled with pigeons; the light of noon-day was obscured as by an eclipse; the dung fell in spots, not unlike melting flakes of snow; and the continued buzz of wings had a tendency to lull my senses to repose.”

- “I rose and, counting the dots then put down, found that 163 had been made in twenty-one minutes. I traveled on, and still met more the farther I proceeded.”

On the “Woodsman” Life

Audubon cultivated a persona as the “American Woodsman”—a rugged frontiersman who preferred the forest to the city.

- “Hunting, fishing, drawing, and music occupied my every moment; cares I knew not, and cared naught about them.”

- “I know I am not a scholar, but meantime I am aware that no man living knows better than I do the habits of our birds.”

- “In my deepest troubles, I frequently would wrench myself from the persons around me, and retire to some secluded part of our noble forests.”

On Conservation and Loss

While he shot thousands of birds for his art, he was also among the first to recognize that the American wilderness was finite.

- “The Fur Company may be called the exterminating medium of these wild and almost uninhabitable regions, which cupidity or the love of money alone would induce man to venture into. Where can I now go and find nature undisturbed?” (Written later in life during his Missouri River expedition, when he realized the buffalo and beaver were disappearing.)

- “But hopes are shy birds flying at a great distance, seldom reached by the best of guns.”

On the “Character” of Birds

He often projected human personalities onto his subjects (anthropomorphism), which made his writing entertaining but sometimes scientifically controversial.

- On the Bald Eagle: “The Bald Eagle… is a bird of bad moral character; he does not get his living honestly.”

- On the Mockingbird: “There is probably no bird in the world that possesses all the musical qualifications of this king of song, who has derived all from Nature’s self.”

- On the Mallard: “Look at that mallard as he floats on the lake… he has marked you, and suspects that you bear no goodwill towards him, for he sees that you have a gun.”

Note on Misattributed Quotes: You will often see the quote “We do not inherit the earth from our ancestors, we borrow it from our children” attributed to Audubon. There is no evidence that he ever wrote this; it is likely a modern proverb (or a Wendell Berry variation) that was attributed to him because it fits his legacy.

John James Audubon Chronological Table

The publication of The Birds of America (1827–1838) did not happen in the order Audubon painted the birds. He released them in “fascicles” (sets of 5) containing a mix of large and small birds to keep subscribers interested.

However, by reconstructing his travels, we can compile a chronological table of the dates on which he actually encountered and painted these famous species.

Chronology of Masterpieces: When the Birds Were Painted

| Year | Location | Bird Species (Plate #) | Story & Significance |

| 1820 | Kentucky / Mississippi River | Wild Turkey (Plate 1) | The bird that started it all. Painted during his initial flatboat journey down the Mississippi. He chose this “Great American Cock” to be Plate #1 because he believed it, not the Eagle, should be the national symbol. |

| 1821 | Louisiana | Bird of Washington (Plate 11) | The Fake Bird. Audubon painted a massive eagle, which he claimed was a new species, larger than the Bald Eagle. It was likely just an immature Bald Eagle, but he fabricated the species to impress scientists. |

| 1821 | Louisiana | Great Blue Heron (Plate 211) | Painted near New Orleans. This plate is famous for the background—a distinct, moody oil-paint landscape that contrasts with the watercolor bird. |

| 1824 | New Jersey | Peregrine Falcon (Plate 16) | Painted during his failed trip to Philadelphia. He depicted them feeding on a Green-winged Teal with brutal realism, showing the “red in tooth and claw” nature of predation. |

| 1825 | Louisiana (St. Francisville) | Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Plate 66) | Painted in the “Happy Land” of the Louisiana woods. He depicted three birds stripping bark from a tree. Today, this bird is extinct (or critically endangered), making the plate a haunting historical record. |

| 1825 | Louisiana | Carolina Parakeet (Plate 26) | Extinct. He painted seven of them clustered on a cocklebur plant. He noted they were pests that farmers shot in baskets; they went extinct in 1918. |

| 1829 | Mississippi River | Bald Eagle (Plate 31) | The “Do-Over.” He had painted an eagle in 1820, but hated it. In 1829, he shot a massive male and painted this iconic version. Note: He originally painted it eating a Goose, but changed it to a Catfish later to avoid offending British sensibilities. (Actually, the catfish version is the famous one.) |

| 1831 | Florida Keys | Great White Heron (Plate 281) | A major discovery. Audubon was the first to realize this all-white bird was a distinct form (or species) separate from the Great Blue Heron. |

| 1832 | Florida Keys | American Flamingo (Plate 431) | Perhaps his most striking graphic design. He observed flocks of them in Florida (where they are rare today) and painted the bird in a contorted pose to accommodate its long neck on the paper. |

| 1833 | Labrador, Canada | Labrador Duck (Plate 332) | Extinct. Painted during his cold, miserable expedition north. He called this the “Pied Duck.” It went extinct just 45 years later (1878), making this one of the few life studies in existence. |

| 1833 | Labrador, Canada | Great Cormorant (Plate 266) | This plate is famous not for the bird, but for the background. It features a detailed rendering of his ship, the Ripley, anchored in the distance. |

| 1837 | Texas (Galveston) | Harris’s Hawk (Plate 392) | During his expedition to the Republic of Texas, he discovered this “Bay-winged Hawk” and named it after his friend and financier, Edward Harris. |

| 1843 | Missouri River | Western Meadowlark | The Last Discovery. On his final expedition (for the mammal book), he noticed that Meadowlarks in the Dakotas sang a different song from those in the East. He successfully identified them as a new species, proving his ear was as good as his eye. |

The “Subscriber” Timeline (Publication)

While he painted them over decades, the world saw them in this order:

- 1827-1830: Plates 1–100 (The “Blockbusters” like the Turkey and Parakeet).

- 1831-1834: Plates 101–200 (The Waterbirds and Florida species).

- 1834-1836: Plates 201–300 (The “filler” songbirds and Labrador species).

- 1836-1838: Plates 301–435 (The Western species and final rarities).

John James Audubon History

Plate 76 of The Birds of America by Audubon showing a northern bobwhite under attack by a young red-shouldered hawk, painted in 1825

(Wiki ImageBy www.RestoredPrints.com, Attribution, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5644483)

John James Audubon’s life was a series of dramatic reinventions. He transformed himself from an illegitimate French naval cadet into a bankrupt American merchant, and finally into the “American Woodsman” who created the most famous natural history book in the world.

Here is the history of the man who painted life-size portraits of America’s birds.

1. The Secret Origin (1785–1803)

Audubon was not born in Louisiana, as he often claimed to hide his “shameful” past.

- Birth: He was born Jean Rabin in 1785 in Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti). He was the illegitimate son of a French naval officer and a French chambermaid (Jeanne Rabin), who died shortly after his birth.

- Escape to France: To save him from the slave revolts in the Caribbean, his father took him to France, where he was legally adopted and renamed Jean-Jacques Fougère Audubon.

- Fleeing Napoleon: In 1803, at age 18, his father sent him to the United States to manage a family lead mine in Pennsylvania—and, more importantly, to avoid conscription into Napoleon’s army.

2. The “Mill Grove” Years & The First Banding

He settled at Mill Grove, near Philadelphia. While he was terrible at managing the mine, he was brilliant at studying nature.

- The Experiment: In 1804, he conducted the first bird-banding experiment in North America. He tied silver threads to the legs of Eastern Phoebes to see if they returned to the same nest the following year. (They did.)

- Lucy: It was here that he met Lucy Bakewell, the daughter of a wealthy neighbor. She would become his wife and the financial backbone of his future career.

3. The Bankruptcy that Created the Artist (1808–1819)

Audubon tried to be a businessman for over a decade. He opened general stores in Kentucky and invested in a steam mill in Henderson.

- The Crash: The mill failed spectacularly in 1819. Audubon went bankrupt and was briefly thrown into debtors’ prison.

- The Pivot: Stripped of his assets, he had nothing left but his gun and his paintbrushes. He made a radical decision: he would travel down the Mississippi River to paint every bird in North America, life-size.

4. The Birds of America (1826–1838)

Rejected by the scientific establishment in Philadelphia (who saw him as an uneducated frontiersman), Audubon took his portfolio to England in 1826.

- The Persona: He recognized that the British favored the idea of the “wild American.” He grew his hair long, greased it with bear fat, and marketed himself as the “American Woodsman.” It worked. He became an overnight celebrity.

- The “Double Elephant”: To paint birds life-size, he needed the largest paper available—the “Double Elephant” folio (approx. 39 x 26 inches).

- The Subscription: He sold the book by subscription to wealthy patrons (including the King of England) to fund the engraving. It took 12 years to complete all 435 plates.

5. The Final Chapter: The Quadrupeds

After the success of his birds, Audubon settled in New York (on an estate in what is now Washington Heights) and turned his attention to mammals.

- The Missouri Expedition: In 1843, at age 58, he traveled up the Missouri River to document bison, wolves, and bears for his final work, The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America.

- The Decline: By the late 1840s, Audubon’s eyesight failed, and he succumbed to dementia (likely Alzheimer’s). He died in 1851, leaving his sons and Lucy to finish the mammal project.

6. Modern Re-evaluation

Historians today grapple with the complexities of his character.

- Scientific Fraud: He is known to have fabricated species (like the “Carbonated Warbler” and “Bird of Washington”) to prank rivals or sell subscriptions.

- Slavery: Recent scholarship has highlighted that Audubon bought and sold enslaved people to finance his expeditions and opposed the abolitionist movement, complicating his legacy as a conservation hero.

Would you like to explore the specific “Mystery Birds” he painted that have never been seen since, or learn more about his rivalry with Alexander Wilson, the “Father of American Ornithology”?

John James Audubon: Eight of the Favorite Birds

John James Audubon’s masterpiece, The Birds of America, contains 435 hand-colored plates. The most iconic birds are those that demonstrate the artistic scale of the project, symbolize the American wilderness, or serve as a permanent record of an extinct species.

Here are eight of the most significant and famous birds documented by Audubon:

- Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) 🦃

- Significance: This was Plate I (Plate 1) of the entire work. Audubon chose the largest, most spectacular native bird to lead the collection, immediately establishing the grand scale and artistic ambition of his project.

- American Flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber) 💖

- Significance: The plate featuring the Flamingo is one of the most famous for demonstrating the sheer size of the double-elephant folio. Audubon had to contort the bird’s neck into a graceful “S” curve to fit it onto the massive sheet of paper, life-size.

- Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) 🕊️

- Significance: This plate is a poignant memorial to a species that was driven to extinction in the early 20th century. Audubon’s detailed illustration is one of the best historical records of the bird that once flew in flocks numbering billions.

- Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis) 🦜

- Significance: Like the Passenger Pigeon, this bird is now extinct. It was the only native parrot species in the eastern U.S., and its illustration is a valuable record of its brilliant, lost coloration.

- Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) 🦅

- Significance: As the national symbol of the United States, the inclusion of the flag was culturally crucial. Audubon’s dynamic and dramatic depiction helped solidify its iconic status in the American imagination.

- Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) 🔴

- Significance: This magnificent bird is either critically endangered or extinct. Audubon’s illustration captures its striking plumage and prominent ivory bill, serving as a primary source for its appearance before its final decline.

- Great White Heron (Ardea herodias occidentalis) ⚪

- Significance: Audubon considered this distinct, all-white bird to be a separate species (though it is now a subspecies of the Great Blue Heron). His depiction of the bird in the Florida Keys highlights his expeditions to the country’s remote southern reaches.

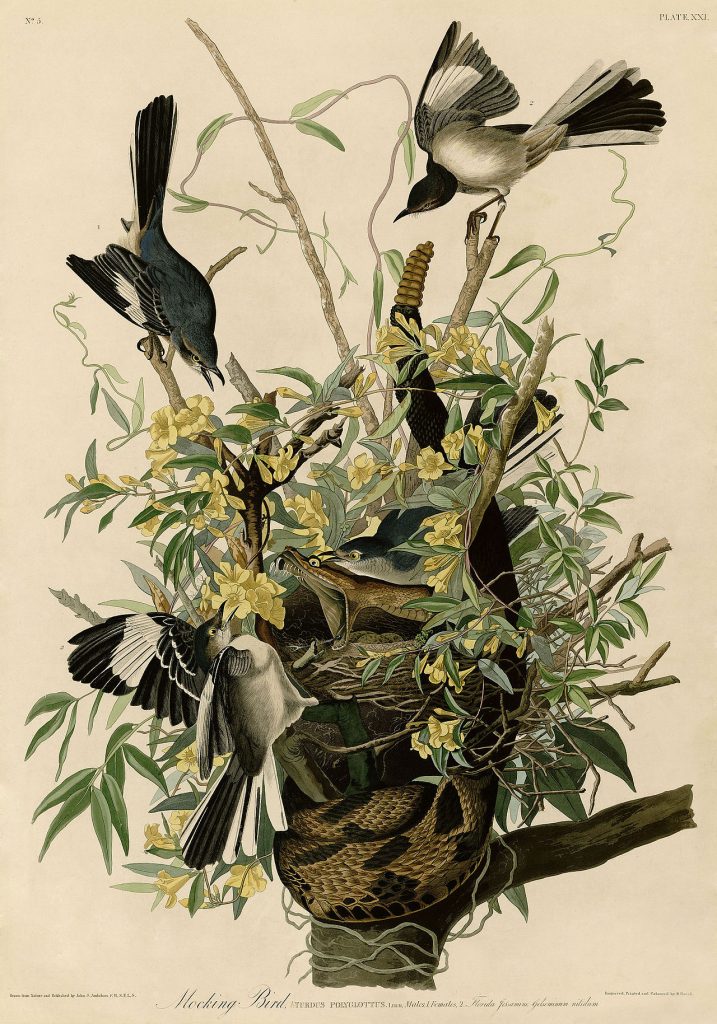

- Common Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) 🎶

- Significance: A highly popular subject, his plate is known for its dramatic composition, showing two Mockingbirds aggressively defending their nest against a rattlesnake. It illustrates Audubon’s style of presenting birds in dynamic, natural, and often violent interaction.

John James Audubon: Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) 🦃

Female wild turkey with young, from Birds of America by John James Audubon

(Wiki Image By John James Audubon – University of Pittsburgh, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8713630)

For John James Audubon, the Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) was not just a bird; it was the symbol of the American wilderness.

It is no accident that when Audubon published his masterpiece, The Birds of America, he chose the Wild Turkey as Plate 1. He bypassed the Bald Eagle (which he considered a scavenger of “bad moral character”) to give the place of honor to the bird he believed was the true spirit of the New World.

Here is the story behind the most famous bird in art history.

- Plate 1: The “Great American Cock”

When subscribers opened the first fascicle of The Birds of America in 1827, they were confronted with a life-size image of a male Wild Turkey striding through a cane brake.

- The Scale: This plate defined the physical size of the entire project. To paint a life-size turkey (approximately 4 feet tall), Audubon had to use the largest paper available, known as the “Double Elephant Folio” (approximately 26 x 39 inches).

- The Detail: The engraving captures the iridescent sheen of the feathers—bronze, copper, and green—and the bumpy, colorful texture of the caruncles (wattles) on the neck. It announced to the scientific world that this was not just a book; it was an experience.

- The Engraver: The plate was engraved initially by W.H. Lizars in Edinburgh. It is considered one of the finest examples of aquatint.

- The Franklin Connection

Audubon aligned himself with Benjamin Franklin in the “Turkey vs. Eagle” debate regarding the national symbol.

- The Eagle: Audubon famously wrote that the Bald Eagle was “a bird of bad moral character… he does not get his living honestly” (referring to the eagle stealing fish from the Osprey).

- The Turkey: He agreed with Franklin that the Turkey was “a much more respectable bird, and with a true original Native of America… a Bird of Courage.”

- The “American Woodsman” Persona

Audubon cultivated a public image in Europe as a rustic “American Woodsman” with long hair and buckskins.3 The Wild Turkey was the perfect mascot for this brand. It represented the abundant, untamed forest that Europeans had cut down centuries ago, but that still thrived in America.

- Plate 6: The Female and Young

While Plate 1 (The Male) gets all the glory, Audubon also painted the female (hen) and her poults in Plate 6. This painting is arguably more dynamic, depicting a mother turkey looking back in alarm, signaling her chicks to hide, likely spotting a predator (perhaps the viewer).

Comparison of the Plates

| Feature | Plate 1 (The Male) | Plate 6 (The Female & Young) |

| Subject | A single Gobbler (Tom). | A Hen with several Poults. |

| Mood | Majestic, confident, displaying. | Alert, protective, defensive. |

| Background | A cane brake (evoking the South). | A Virginia landscape. |

| Significance | The “Opener” of the masterpiece. | Shows Audubon’s interest in behavior/family. |

| Model | Based on a bird Audubon shot. | Based on careful observation of brooding. |

John James Audubon: American Flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber) 💖

Phoenicopterus ruber, the Greater Flamingo. Drawn by John James Audubon for his book The Birds of America

John James Audubon’s relationship with the American Flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber) is a story of intense longing, artistic frustration, and eventual triumph.

Here is the story behind the bird that Audubon called “that glorious creature.”

- The “Heart” Moment (💖)

The heart emoji in your prompt is fitting because Audubon was emotionally overwhelmed by this bird.

In May 1832, while sailing near Indian Key in the Florida Keys, he saw a flock of flamingos for the first time. His journal entry captures his sheer awe:

“Ah! reader, could you but know the emotions that then agitated my breast! … I thought I had now reached the height of all my expectations, for my voyage to the Floridas was undertaken in a great measure for the purpose of studying these lovely birds in their own beautiful islands.”

- The Artistic Challenge: Plate 431

The resulting illustration, Plate 431 in The Birds of America, is one of his most famous and graphically striking works, but it arose from a significant logistical problem.

- The Size Issue: Audubon insisted on painting birds life-size. The American Flamingo stands about 5 feet tall, but his “Double Elephant Folio” paper was only roughly 39 x 26 inches.

- The Solution: To fit the giant bird on the page, Audubon forced it into a bending posture. While this appears to be a feeding pose, it was actually a compositional device to compress the bird’s massive height into the frame.

- Anatomical Sketches: If you look closely at the plate, you will see floating sketches of the beak and tongue. These anatomical studies, which he included to illustrate the unique filtration system of the flamingo’s bill, were of particular interest to him.

- The “Secret” of the Painting

Despite seeing them in Florida, Audubon actually failed to collect a specimen there. The birds were too wary, and he couldn’t get close enough to shoot one (the standard method of bird study at the time).

He returned to London without his prize. The famous painting was created in 1838, based on skins sent to him from Cuba. He had to rely on his memory of the Florida sunlight to recreate the vivid colors, which makes the plate’s vibrancy even more impressive.

- Status in the US

Audubon’s writings are critical to modern conservation. For a long time, people believed flamingos were not native to Florida and were just escapees from zoos. However, Audubon’s detailed 1832 accounts of massive flocks in the Keys help prove that they are indeed a native species that plume hunters nearly wiped out, and they are only now beginning to return.

Would you like to know more about his specific expedition to the Florida Keys (1832), or perhaps the “mystery bird” known as the Carbonated Warbler that he painted but hasn’t been seen since?

John James Audubon: Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) 🕊️

Billing pair by John James Audubon, from The Birds of America, 1827–1838. This image has been criticized for its scientific inaccuracy.

(Wiki Image By John James Audubon – https://archive.org/stream/birdsofamericafr05audu#page/n39/mode/2up, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8903097)

John James Audubon’s relationship with the Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) is one of the most haunting chapters in American natural history. He witnessed the bird at its absolute peak, describing a natural phenomenon that sounds like fantasy to modern ears, yet he also lived just before the collapse that would wipe the species from the face of the earth.

Here is the story behind the bird that once darkened the sky.

- The “Eclipse” of 1813 (🕊️)

The pigeon emoji in your prompt is tragic because it represents a bird that existed in the billions but is now entirely gone.

In the autumn of 1813, Audubon was riding from his home in Henderson, Kentucky, to Louisville when he encountered a migration of Passenger Pigeons. His account is famous for its staggering scale:

- The “Eclipse”: He wrote, “The light of noon-day was obscured as by an eclipse.” The sky was literally black with birds.

- The Math: Being a man of science, he tried to count them. He marked a dot on a piece of paper for every flock that passed. After 21 minutes, he had marked 163 dots and gave up because they were “pouring in in countless multitudes.”

- The Duration: The stream of birds did not stop for three days. The sound of their wings was like a stiff gale at sea, and the falling dung was like “melting flakes of snow.”

- The Painting: Plate 62

His illustration of the Passenger Pigeon (Plate 62 in The Birds of America) captures an intimate moment amidst the chaos of the flocks.

- The Composition: It depicts a male and a female in a billing (touching beaks) courtship ritual. The male is passing food to the female, a tender moment that contrasts with the species’ reputation for destructive, locust-like feeding frenzies.

- The Critique: Later ornithologists criticized this plate as “unscientific.” They argued that Passenger Pigeons stood side by side when billing, not one above the other as Audubon depicted them. Audubon likely altered the pose for artistic composition—a common habit of his.

- Audubon’s Blind Spot

Perhaps the most chilling part of Audubon’s writing on this bird is his optimism.

Despite witnessing the mass slaughter of these birds (people would knock them out of trees with poles and feed them to pigs because they were so cheap and plentiful), Audubon believed they were indestructible. He wrote:

“It is here to-day and elsewhere to-morrow, and no ordinary destruction can lessen them.”

He was wrong. The last Passenger Pigeon, named Martha, died alone in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914, roughly 75 years after Audubon painted them. The species went from a population of ~3-5 billion (40% of all birds in North America) to zero in a single human lifetime.

John James Audubon: Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis) 🦜

Carolina parakeets by John James Audubon (1833)

John James Audubon’s depiction of the Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis) is a colorful but tragic memorial to the only parrot species native to the eastern United States. Although they were once a vibrant part of the American landscape, Audubon documented the specific behaviors that ultimately led to their demise.

Here is the story behind the lost “Parrot of the Carolinas.”

- The Painting: Plate 26 (🦜)

The parrot emoji is aptly colorful for Plate 26 in The Birds of America, widely regarded as one of Audubon’s most dynamic compositions.

- The Scene: It features seven parakeets clambering over a branch, displaying a “riot of emerald, lime, and moss green” with brilliant yellow and orange heads.

- The “Cocklebur” Detail: The birds are shown feeding on cockleburs (a rough, prickly weed). This was a deliberate choice by Audubon. Farmers disliked cockleburs. They damaged wool and crops, whereas parakeets were beneficial because they ate the seeds. However, farmers also disliked the parakeets for raiding fruit orchards, despite the benefits they provided in controlling weeds.

- The Juvenile: If you look closely at the group, one bird has a green head instead of yellow. This is a juvenile, included by Audubon to show the species’ life cycle—a cycle that would soon be broken forever.

- The Fatal Flaw: “Mourning” Behavior

Audubon documented a specific behavioral trait that made the Carolina Parakeet highly vulnerable to extinction. He noted that they were intensely social and loyal.

- The Slaughter: When a farmer shot into a flock, the survivors would not fly away. Instead, they would hover and scream over their fallen companions, circling back again and again.

- Audubon’s Observation: He wrote that this behavior allowed a farmer to “destroy nearly the whole of them” in a few minutes, as the birds refused to abandon the dead. They were victims of their own social bonds.

- The “Phantom” Decline

Similar to the Passenger Pigeon, Audubon witnessed the Carolina Parakeet’s transition from abundance to scarcity.

- Early Abundance: In his earlier travels, he described them as so numerous that they were seen as a nuisance, “covering the stacks of grain.”

- Later Warning: By the 1830s, he was already sounding the alarm, noting, “In some districts, where twenty-five years ago they were plentiful, scarcely any are now to be seen.”

- The Final Echo

The extinction of the Carolina Parakeet has a heartbreaking connection to the Passenger Pigeon.

- Incas and Lady Jane: The last captive Carolina Parakeet was a male named Incas. He died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1918, reportedly of “grief” shortly after his mate, Lady Jane, passed away.

- The Cage: Incas died in the exact same cage where Martha, the last Passenger Pigeon, had died four years earlier. That single cage in Cincinnati became the silent ground zero for two of America’s greatest avian tragedies.

Would you like to learn about the Great Auk, the “penguin of the north” that Audubon also documented before its extinction, or perhaps the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, the “Lord God Bird”?

John James Audubon: Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) 🦅

Feeding on catfish and other various fish. Painted by John James Audubon.

(Wiki Image By John James Audubon – University of Pittsburgh, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8716137)

John James Audubon’s relationship with the Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) was complicated. While he recognized it as the national symbol, he personally viewed it as a bird of “bad moral character”. He was even involved in a scientific scandal regarding a “new” species of eagle that likely never existed.

Here is the story behind Audubon’s eagle.

- The “Catfish” Portrait: Plate 31 (🦅)

The most famous Audubon image of this bird is Plate 31, which depicts an adult Bald Eagle feasting on a catfish.

- The Original Version: In his original watercolor, Audubon actually painted the eagle eating a Goose. However, when it came time to print the book, he worried that depicting the national bird killing livestock (or a game bird) would upset Americans.

- The Switch: He swapped the goose for a catfish in the final engraving to make the bird seem more “noble” (or at least less destructive to farmers), though the catfish looks somewhat surprised to be there.

- The “Washington Sea Eagle” Scandal

This is one of the biggest controversies in Audubon’s career. In Plate 11, he painted a massive bird he called the “Bird of Washington” (Falco washingtonii).

- The Claim: He claimed it was a new, giant species of eagle he discovered in the Great Lakes region—larger than a Bald Eagle and a “true” species to rival the European Golden Eagle. He named it after George Washington to help sell his book to American patriots.

- The Reality: No such bird exists. Modern ornithologists are sure that Audubon either misidentified a large immature Bald Eagle (which lacks the white head) or, as some critics suggest, fabricated the species entirely to generate hype and secure subscribers. It remains a “phantom species” in his catalog.

- “Bad Moral Character”

Audubon agreed with Benjamin Franklin’s famous disdain for the Bald Eagle. While he admired their flight, he found their behavior lazy.

- The Thievery: Audubon frequently observed Bald Eagles harassing Ospreys (Fish Hawks) to steal their catches rather than fishing for themselves.

- The Quote: In his writings, Audubon echoed Franklin almost word-for-word, stating: “The Bald Eagle… is a bird of bad moral character; he does not get his living honestly.” He frankly preferred the Wild Turkey as a more respectable, industrious, and native symbol of America.

Would you like to learn about the Golden Eagle (which Audubon also painted) and the intense “duel” he had with one while trying to study it?

John James Audubon: Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) 🔴

Painting by John James Audubon

(Wiki Image By John James Audubon – University of Pittsburgh, Audubon’s Birds of America, Darlington Digital Library, Image, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4055655)

John James Audubon’s relationship with the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) is one of reverence, marked by the same tragic foreshadowing found in his other extinct-bird portraits. He didn’t just see a bird; he saw royalty.

Here is the story behind the “Great Chieftain.”

- The “Great Chieftain” and the “Vandyke” (🔴)

Audubon didn’t call it the “Lord God Bird” (that was a popular folk name). In his writings, he elevated it above all others, referring to it as the “Great Chieftain of the Woodpecker Tribe.”

He was so struck by its striking black-and-white plumage and noble bearing that he compared it to the work of the famous Baroque painter Anthony van Dyck.

- The Quote: Audubon wrote that whenever he saw one flying, he would mentally exclaim: “There goes a Vandyke!”

- The Reason: He felt the bird’s glossy black body, sharp white markings, and brilliant yellow eye mimicked the bold, high-contrast style of a Van Dyck portrait.

- Plate 66: A Family Portrait

Plate 66 in The Birds of America is one of his most dynamic group compositions.

- The Scene: It depicts three birds—two males with their famous red crests and one female with a black crest—on a dead tree.

- The Behavior: They are shown stripping bark from the tree, which highlights their immense physical strength. Audubon noted that a single Ivory-bill could strip a tree of 20 to 30 feet of bark in just a few hours to get to the beetles underneath.

- The Sound: He described their call not as a song, but as a “plaintive” and repeated note sounding like “pait, pait, pait,” which he said could be heard for half a mile.

- The “Ornament” Trade

Audubon documented the early pressures that would eventually help drive the species to extinction (along with habitat loss).

- The Value: He noted that the birds were shot not only for sport but also for their beautiful ivory-colored bills.

- The Market: Travelers and Native Americans prized the bills as “amulets” or ornaments. Audubon reported that steamboat passengers paid 25 cents for two or three woodpecker heads at river stops. He also described seeing “entire belts of Indian chiefs closely ornamented with the tufts and bills of this species.”

- A Case of Mistaken Identity?

There is a famous story about an Ivory-billed Woodpecker that was captured, left in a hotel room, and proceeded to destroy the entire room (pecking through the mahogany table and plaster walls) in a fit of rage.

- Clarification: This story is often attributed to Audubon, but it actually belongs to his rival, Alexander Wilson. Audubon did shoot and collect many ivory-billed woodpeckers, but the “hotel room destroyer” was Wilson’s captive.

John James Audubon: Great White Heron (Ardea herodias occidentalis) ⚪

Widespread and familiar (though often called ‘crane’), the Great Blue Heron is the largest in North America. Usually seen standing silently along inland rivers or lakeshores, or flying high overhead, with slow wingbeats, its head hunched back onto its shoulders. Highly adaptable, it thrives around all kinds of waters from subtropical mangrove swamps to desert rivers to the coastline of southern Alaska. With its variable diet, it can spend the winter farther north than most herons, even in areas where most waters freeze.

(https://www.audubon.org/art/birds-america/great-white-heron)

John James Audubon’s relationship with the Great White Heron (Ardea herodias occidentalis) is a classic example of his obsession with discovery and his penchant for turning wild animals into house guests (with disastrous results).

Here is the story behind the “Ghost of the Keys.”

- The “New” Giant (⚪)

The white circle emoji is perfect, but for Audubon, this wasn’t just a color variant—it was a career milestone.

- The Discovery: In 1832, while exploring the Florida Keys, Audubon became the first scientist to describe this bird. He was convinced it was a totally new species, distinct from the Great Blue Heron. He named it Ardea occidentalis.

- Modern Science: Today, ornithologists consider it a “white morph” or subspecies of the Great Blue Heron, found almost exclusively in southern Florida. But for Audubon, it was the “largest heron in North America,” a prize he had hunted for days under the “burning sun” of the Keys.

- Plate 281: The Key West Portrait

Plate 281 in The Birds of America is one of the few plates where the background is as famous as the bird.

- The Setting: The massive white bird is set against a dark, stormy sky to make the plumage pop. If you look at the horizon, you can clearly see the town of Key West as it looked in the 1830s.

- The Scale: To emphasize the bird’s size (it is larger than the standard Great Blue), he painted it in a hunched, heavy posture, occupying almost the entire “Double Elephant” page.

- The “Monster” House Guests

The most entertaining part of this story happened after the expedition. Audubon captured several live Great White Herons and brought them back to Charleston, South Carolina, to stay with his friend (and fellow naturalist) Reverend John Bachman. It was a disaster.

- The Appetite: Audubon noted that they were insatiable. A single bird could swallow a “bucketful of mullets” in minutes.

- The Violence: These were not gentle pets. They terrorized Bachman’s yard, spearing chickens, ducks, and grown fowls.

- The Cat Incident: The final straw came when one of the herons walked up to a domestic cat sleeping in the sun and pinned it to the floor with its beak, killing it instantly. Bachman eventually had to get rid of them to save his remaining livestock (and family).

- A “Sedate” Killer

Audubon admired the bird’s “sedate” nature compared to other herons. He described how they would stand statue-still for hours, only to strike with terrifying speed. He viewed them as the “aristocrats” of the swamp—elegant, silent, and deadly.

Would you like to learn about the Zenaida Dove, which Audubon named after his wife’s middle name, or perhaps the Roseate Spoonbill, another pink wonder he chased in the Florida Keys?

John James Audubon: Common Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) 🎶

Painting by John James Audubon

(Wiki Image By John James Audubon – 21_Mocking_Bird.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13259783)

John James Audubon’s depiction of the Common Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) is not just a portrait of a bird; it is the center of one of the fiercest scientific feuds of his career. It represents his refusal to paint “stuffed” birds in static poses, choosing instead to capture the raw violence of nature.

Here is the story behind the bird Audubon called the “King of Song.”

- The “Rattlesnake Controversy”: Plate 21 (🎶)

The music note emoji is ironic here because the most famous thing about Plate 21 isn’t the song—it’s the scream.

- The Scene: The plate depicts four Mockingbirds in a frantic battle against a Timber Rattlesnake that has climbed a jessamine vine to raid their nest. The birds are shown with their wings flared and beaks open, striking at the snake’s eyes.

- The Scandal: When Audubon released this image, the scientific establishment (led by admirers of his rival, Alexander Wilson) attacked him viciously. They claimed the painting was a lie.

- The Charges: Critics argued that rattlesnakes do not climb trees and that Audubon had fabricated the behavior for dramatic effect. They also mocked the snake’s fangs, which curve slightly outward in the painting, arguing that they are anatomically impossible.

- Vindication (Mostly)

Audubon refused to back down, insisting he had witnessed the event.

- The Climbing: Time eventually proved Audubon right on the main point—rattlesnakes can and do climb trees to hunt birds, especially in the South.

- The Fangs: He was, however, likely wrong about the fangs. Snake fangs curve inward (to hold prey), not outward. It is believed that Audubon exaggerated them to make the snake appear more terrifying, prioritizing the “emotional truth” of the scene over strict anatomical accuracy.

- The “King of Song”

Despite the violent painting, Audubon was deeply moved by the bird’s voice. In his writings, he heaped higher praise on the Mockingbird than almost any other species.

- The Quote: He wrote, “There is probably no bird in the world that possesses all the musical qualifications of this king of song, who has derived all from Nature’s self.”

- The Comparison: He described the Mockingbird as a genius mimic that could fool even the birds it imitated, silencing the entire forest as other species paused to listen to their own calls reflected back to them.

- A “Global” Favorite

The Mockingbird was one of the birds that helped make Audubon famous in Europe. When he brought his paintings to England, the British were accustomed to seeing birds depicted in stiff profile views. Seeing the dynamic, violent, and “American” energy of the Mockingbirds fighting a rattlesnake shocked the art world and established his reputation as the “American Woodsman.”

John James Audubon YouTube links views

Here are some popular YouTube videos about John James Audubon, his life, and his famous work The Birds of America, including their approximate view counts.

Documentaries & Biographies

- “JOHN JAMES AUDUBON: THE BIRDS OF AMERICA”

- Views: ~80,000

- Channel: PublicResourceOrg

- Description: A classic 1986 documentary produced by the National Gallery of Art that explores Audubon’s life, his travels, and the creation of his masterpiece.

- Link: Watch here

- “John James Audubon – STORYTIME!”

- Views: ~15,000

- Channel: HiGASFY Productions

- Description: A biographical storytelling video focused on his history and impact, suitable for a general audience.

- Link: Watch here

- “A History of John James Audubon”

- Views: ~4,100

- Channel: Kentucky History Channel

- Description: A concise history focusing on his time in Kentucky, where he lived and worked as a merchant before finding fame.

- Link: Watch here

On “The Birds of America” (The Book)

- “Audubon’s Birds of America book”

- Views: ~65,000

- Channel: Lost Bird Project

- Description: A close-up look at the “Double Elephant Folio,” showing the immense size and detail of the actual physical book housed in a rare book collection.

- Link: Watch here

- “How Audubon’s Birds of America Changed Natural History”

- Views: ~62,000

- Channel: Sotheby’s

- Description: A video produced by the famous auction house detailing why this book is considered one of the most valuable and important books ever printed.

- Link: Watch here

Art & Lectures

- “John James Audubon: Life-Sized and Larger than Life”

- Views: ~16,000

- Channel: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Description: A deeply educational 90-minute lecture by a curator, analyzing Audubon as both an artist and a historical figure.

- Link: Watch here

John James Audubon Books

John James Audubon published two major monumental works during his lifetime, separating the illustrations from the text to avoid British copyright laws (which required free copies of any “book” with text to be given to libraries).

Here are the primary books authored by Audubon.

1. The Birds of America (1827–1838)

This is his masterpiece and the reason he is famous. It is technically a collection of engravings, not a traditional “book” with text.

- Format: Published in the “Double Elephant Folio” size (approx. 39 x 26 inches) to depict birds life-size.

- Content: Contains 435 hand-colored, life-size prints of North American birds.

- Editions:

- Havell Edition (1827–1838): The original, massive London edition.

- Octavo Edition (1840–1844): A smaller, more affordable version (about 7 x 10 inches) that included the text and was widely popular in the US.

2. Ornithological Biography (1831–1839)

This is the text companion to the plates. Because the Birds of America plates contained no text, Audubon published a separate 5-volume set to accompany them.

- Content: It contains the life histories, behaviors, and anecdotes of the birds depicted in the plates. It is famously written in a romantic, “American Woodsman” style.

- Collaborator: The Scottish naturalist William MacGillivray helped edit Audubon’s rough frontier grammar and added the scientific anatomical details.

3. The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America (1845–1848)

After finishing the birds, Audubon attempted to do the same thing for mammals.

- Content: A collection of 150 hand-colored lithographs of North American mammals (bison, wolves, squirrels, etc.).

- Collaborators: This was a family project. His friend John Bachman wrote the scientific text, and his sons, John Woodhouse Audubon and Victor Gifford Audubon, did much of the painting and background work as Audubon’s health declined.

4. A Synopsis of the Birds of North America (1839)

A single-volume scientific index that served as a systematic catalog of the birds he had identified. It was a practical “checklist” for scientists, lacking the artistic flair of his other works.

5. The Missouri Journal (Posthumous)

Although not published as a book during his lifetime, his journals from his 1843 expedition up the Missouri River offer a raw account of the American West before widespread settlement. These are often collected today in volumes titled Audubon’s Journals.

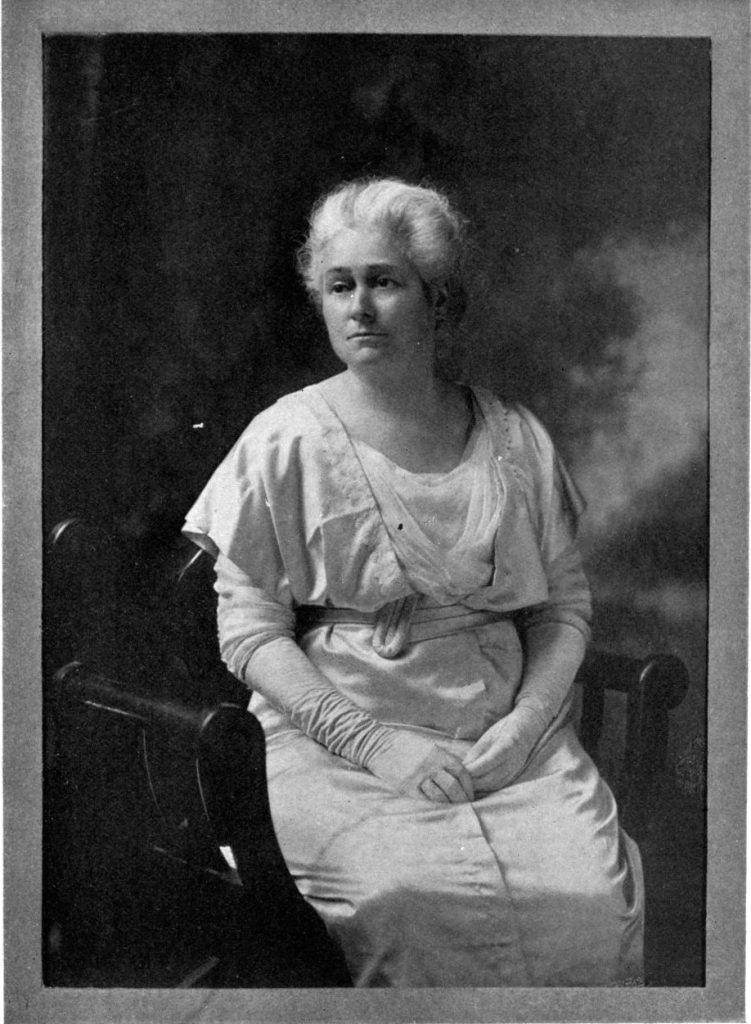

Florence Merriam Bailey (1863–1948)

Bailey in 1916

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – Bird Lore, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=63789058)

Florence Merriam Bailey Quotes

Florence Merriam Bailey’s writing was a quiet revolution. Unlike the dry, scientific catalogs of her male contemporaries, her books were invitations. She wrote to persuade women, children, and amateur naturalists that birds were neighbors to be understood rather than specimens to be collected.

Here is a curation of her most defining quotes, categorized by the philosophies she pioneered.

On the “Opera Glass” Revolution

Bailey was the primary voice arguing that you could study ornithology without a shotgun. She championed the use of “opera glasses” (the precursor to modern binoculars).

- “The student who goes out with a gun… sees only the terror of the hunted… but the student who goes out with the opera-glass… learns the secrets of the home life.” (This is her manifesto. It defines the shift from 19th-century collection to 20th-century observation.)

- “A bird in the bush is worth two in the hand.” (A clever twist on the old proverb, emphasizing that a living bird is scientifically more valuable than a dead one.)

- “To the person who wants to know the birds… the gun is a hindrance.”

On the “Personality” of Birds

Bailey famously anthropomorphized birds (giving them human traits). While “serious” scientists scoffed at this, she knew it was the most effective way to make the public care about conservation.

- “We are not studying dead specimens… but living creatures with wills and characters of their own.”

- “The question is not ‘What is that bird?’ but ‘Who is that bird?'” (This sentiment captures her focus on individual behavior—the “winsome” tilt of a head or the “devotion” of a parent.)

- “Like other ladies, the little feathered bride is often hard to please.” (describing a female bird inspecting a nest site)

On the Plume Trade (The “Hat” Controversy)

Bailey was a general in the war against the fashion industry, which was slaughtering millions of egrets and herons for women’s hats. Her writing was designed to make wearing feathers socially shameful.

- “She who wears the plumage of the Snowy Heron… wears the badge of cruelty.”

- “How can a woman who is a mother wear a decoration that cost the life of a mother bird and the starvation of her helpless young?” (This was her most powerful argument: appealing to the maternal instinct of her readers to save the “mother” birds.)

On the Joy of Birding

Ultimately, she viewed birding as a path to mental health and happiness, a way to escape the “fret” of indoor life.

- “Come out! The air is clear and sweet, the sun is bright… and the birds are waiting for you.”

- “Bird-work… takes one out of doors, and gives a new interest to the world.”

- “If you want to know the birds, you must go to them. They will not come to you.”

On the American West

When she traveled West, she was struck by how the landscape shaped the birds.

- “The desert is a place of strong lights and deep shadows… and the birds are a part of the picture.”

- “To understand the bird, you must understand the tree it lives in.” (A precursor to the modern concept of ecology—linking the Pinyon Jay to the Pinyon Pine.)

Florence Merriam Bailey’s Chronological Bird Table

Florence Merriam Bailey did not produce a single visual masterpiece like Audubon’s Birds of America. Instead, her “chronology” is a timeline of publications that slowly shifted the entire culture of birding from shooting to watching.

Here is the chronological table of her life, tracking her evolution from a nature-loving college student to the supreme authority on Western birds.

Chronology of the “Opera Glass” Revolution

| Year | Location | Book / Event | Key Species & Significance |

| 1886 | Smith College, MA | The Audubon Society Chapters | As a student, she was horrified by the fashion trend of wearing bird hats. She organized the first Audubon Society chapters at Smith, focusing on protecting the Great Egret and Snowy Egret from the plume trade. |

| 1889 | New York | Birds Through an Opera Glass | The First Field Guide. At age 26, she published this compilation of her observations. It focused on common “backyard” birds like the American Robin and Blue Jay, proving that you didn’t need to be a scientist in the jungle to enjoy nature. |

| 1893 | Utah & California | The Health Exile | Diagnosed with tuberculosis (like many of her era), she traveled West for the dry air. This forced relocation introduced her to Western species like the Steller’s Jay and Mountain Bluebird, shifting her focus away from the East. |

| 1896 | Southern California | A-Birding on a Bronco | A memoir of her time riding horses through the valleys of San Diego County. She documented the behavior of the California Quail and Roadrunner, humanizing them for Eastern readers who had never seen them. |

| 1898 | Washington D.C. | Birds of Village and Field | Written for “those who do not use a gun.” She created simple keys based on color (e.g., “Birds with Red”) to help amateurs identify Cardinals and Tanagers without knowing scientific taxonomy. |

| 1899 | The American West | The Partnership | She married Vernon Bailey, the Chief Field Naturalist for the U.S. Biological Survey. They became a scientific power couple, spending decades camping in the wilderness to survey biological zones. |

| 1902 | The Western U.S. | Handbook of Birds of the Western United States | Her Magnum Opus. This 600-page book became the standard reference for Western ornithology for the next 50 years. It combined hard science (measurements) with her signature “biographical” notes on bird personalities. |

| 1917 | Oregon / Washington | The “Red Book” Era | She spent summers in the Pacific Northwest, contributing significantly to the understanding of deep-forest birds such as the Varied Thrush and Spotted Owl, while her husband surveyed mammals. |

| 1928 | New Mexico | Birds of New Mexico | The Masterpiece. At age 65, she published this massive, comprehensive state study. It was the first time a woman had authored such a substantial scientific work. It remains a classic of desert ecology. |

| 1929 | United States | AOU Fellow | In recognition of her lifetime of work, she became the first woman ever elected as a Fellow of the American Ornithologists’ Union. |

| 1931 | United States | The Brewster Medal | She became the first woman to receive the Brewster Medal, the highest honor in American ornithology, for her work on Birds of New Mexico. |

The Evolution of Her “Birding List”

- Early Phase (1880s): Focused on Eastern Songbirds (Thrushes, Warblers) and protection against the millinery (hat) trade.

- Middle Phase (1890s-1910s): Focused on Western Desert & Mountain Species (Towhees, Thrashers, Jays) as she traveled with her husband.

- Late Phase (1920s): Focused on Synthesis—combining all her observations into comprehensive state guides that linked birds to their specific habitats (life zones).

Florence Merriam Bailey History

Florence Merriam Bailey is often called the “First Lady of American Ornithology.” Still, her legacy is even more specific: she is the reason you probably own a pair of binoculars instead of a shotgun.

While men such as Audubon and her own brother defined ornithology as the science of dead specimens, Florence described it as the science of living behavior.

1. The Scientific Royalty (1863–1886)

Florence was born in 1863 in Locust Grove, New York, into a family that was essentially the “Kennedy clan” of natural science.

- The Brother: Her older brother was C. Hart Merriam, the founder of the U.S. Biological Survey (now the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) and the inventor of the concept of “Life Zones.”

- The Tension: She grew up skinning birds for her brother’s collection, but she became increasingly uncomfortable with the idea that you had to kill a bird to know it. She began to wonder if one could study the bird’s life rather than just its anatomy.

2. The Smith College Activist (1886)

While attending Smith College, Florence noticed that nearly every female student was wearing a hat decorated with feathers—or entire stuffed birds.

- The Plume Trade: This was the height of the “hat trade,” which was wiping out egret and heron populations.

- The Revolt: In 1886, she organized an Audubon Society chapter at Smith College (one of the very first). She took the radical step of taking her classmates on bird walks to show them the living creatures they were wearing, believing that “observation breeds affection.”

3. The “Opera Glass” Manifesto (1889)

At age 26, she published Birds Through an Opera Glass.

- The Innovation: This is widely considered the first modern field guide. Before this, bird books were technical manuals for museum curators.

- The Argument: She argued that with a cheap pair of theater glasses (“opera glasses”), anyone—especially women—could study birds. It was a feminist and scientific statement: science belongs to everyone, and it doesn’t require violence.

4. The Western Exile (1893–1899)

Like many people of her era, Florence contracted tuberculosis. Her doctors prescribed the standard cure: move to the dry air of the American West.

- The Pivot: She moved to Utah and California. This forced relocation turned her into an expert on Western birds, a region largely ignored by East Coast ornithologists.

- The Result: She wrote A-Birding on a Bronco (1896), documenting her days riding horseback through the valleys, observing behaviors no one had ever written down.

5. The “Biological Survey” Marriage (1899–1920s)

She married Vernon Bailey, a pioneering field naturalist (and her brother’s colleague). Their marriage was a decades-long camping trip.

- The Team: They spent their lives traversing the West in wagons and tents. Vernon would trap mammals for the government survey, and Florence would document the birds.

- The Synthesis: This partnership allowed her to write Handbook of Birds of the Western United States (1902), which replaced dry technical lists with her lively, behavior-focused descriptions. It remained the standard text for 50 years.

6. The Crowning Achievement (1928–1931)

In her later years, she tackled her most ambitious project: Birds of New Mexico.

- The Scale: It was a massive, comprehensive scientific survey of the state.

- The Recognition: In 1929, she became the first woman Fellow of the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU). In 1931, she became the first woman to win the Brewster Medal, the highest prize in American ornithology.

7. Legacy

Florence Merriam Bailey died in 1948 in Washington, D.C. She lived long enough to see the “opera glass” method completely overtake the “shotgun” method, thanks mainly to the movement she started. She proved that empathy was a valid scientific tool.

Would you like to learn more about her brother, C. Hart Merriam, and his “Life Zone” theory (which explains why you find different birds at different altitudes), or the “Hat Wars” that led to the founding of the National Audubon Society?

Florence Bailey: Eight of the Favorite Birds

Florence Merriam Bailey (1863–1948) was one of the most important pioneers in American ornithology. Unlike the preceding era of “gun ornithologists,” Bailey advocated for non-lethal field study—observing birds through Florence Merriam Bailey (1863–1948) was one of the most important pioneers in modern ornithology, credited with writing the first modern field guide (Birds Through an Opera Glass, 1889) and championing the non-lethal study of birds using binoculars rather than guns.

Her “favorite” birds are generally those she studied extensively in the field over decades of work in the Western U.S. and those she used to demonstrate her conservation principles.

Here are eight significant birds associated with her work:

- Bailey’s Mountain Chickadee (Poecile gambeli baileyae) 🏔️

- Significance: This subspecies of the Mountain Chickadee, found in California, was named in her honor. It represents the lasting scientific recognition of her contributions to Western ornithology.

- Pinyon Jay (Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus) 🌲

- Significance: A highly social corvid found throughout New Mexico and the Western states, this bird was a focus of her detailed studies on behavior and habitat use, as documented in her magnum opus, Birds of New Mexico (1928).

- American Eared Grebe (Podiceps nigricollis californicus) 🦢

- Significance: Mentioned prominently in her Handbook of Birds of the Western United States (1902). Her detailed observation of waterbirds contributed to the scientific record and highlighted the need to protect aquatic habitats.

- Western Tanager (Piranga ludoviciana) 🌈

- Significance: This beautifully colored bird, known for its yellow and red plumage, features in accounts of her field observations. The dramatic contrast of its color against the Western landscape makes it a perfect example of a bird studied primarily through the opera glass (binoculars).

- Robin (Turdus migratorius) 🏡

- Significance: The American Robin served as a common touchstone in her early guides (Birds Through an Opera Glass), used to introduce beginners to the concept of field identification and observation of familiar species.

- Western Bluebird (Sialia mexicana) 💙

- Significance: A common but beloved Western species that often appears in her writings, symbolizing the beauty of the natural habitats she fought to protect.

- Common Nighthawk (Chordeiles minor) 🦇

- Significance: Mentioned in her Oregon fieldwork, this bird’s erratic, nocturnal habits demonstrate her commitment to studying the behavior of living birds, rather than just classifying skins and dead specimens.

- Snowy Heron/Egret (Egretta thula) 👑

- Significance: This wading bird represents her tireless conservation activism. The Snowy Egret was heavily slaughtered for its plumes for the millinery trade. Bailey’s campaigning against this practice helped lead to the passage of the Lacey Act of 1900, which protected migratory birds.

Florence Bailey: Bailey’s Mountain Chickadee (Poecile gambeli baileyae) 🏔️

A mountain chickadee at the crest of the Sandia Mountains

(Wiki Image By Polinova – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=179391012)

For Florence Merriam Bailey, the Mountain Chickadee (Poecile gambeli) was not just a subject of study; it was a companion.

While many male ornithologists of her era sought rare, spectacular, or “manly” birds (like eagles or game birds), Bailey found profound scientific and spiritual value in the small, common birds of the pine forests. It is fitting that the specific subspecies named in her honor, Bailey’s Mountain Chickadee (Poecile gambeli baileyae), is a creature of the high Western mountains she spent her life exploring.

- The Dedication

In 1908, the preeminent Western zoologist Joseph Grinnell described a distinct population of Mountain Chickadees in the mountains of Southern California.

- The Name: He bestowed the scientific name baileyae upon it.

- The Reason: Grinnell wrote that he named it “in honor of Mrs. Florence Merriam Bailey, whose accurate field observations have contributed so much to our knowledge of the life histories of the birds of the west.” This was a massive validation: the academic establishment acknowledged that her “observation” method was equal to their “collection” method.

- The Bird of the “Western Handbook”

Bailey is best known for writing the “Handbook of Birds of the Western United States” (1902). Before this book, there was no comprehensive guide for the birds west of the Mississippi.

- The Connection: The Mountain Chickadee is a strictly Western bird (unlike the Black-capped Chickadee, which is found across the continent). By carrying her name, this bird serves as a living bookmark for her magnum opus.

- Her Description: In her handbook, she described the Mountain Chickadee with her characteristic blend of science and affection:

“He is the most companionable of birds… flitting about the camp and hopping on the table to investigate the sugar bowl… The Mountain Chickadee is a friendly little spirit.”

- The Identification: The “Eyebrow”

To spot the bird that bears her name, you look for the standard Mountain Chickadee traits, but knowing you are seeing the specific baileyae subspecies requires geography.

- The Look: Distinct from other chickadees by the white line (supercilium) above the eye—a “white eyebrow” cutting through the black cap.

- The Baileyae Traits: This subspecies, found in the San Gabriel and San Jacinto Mountains, is slightly larger and grayer than its relatives in the Rockies.

- The Sound: A raspy, lower-pitched chick-a-dee-dee-dee than the Black-capped, often echoing through the dry pine canyons.

- A Symbol of Accessibility

The Mountain Chickadee perfectly represents Bailey’s philosophy.

- It is approachable: It does not fly away; it comes closer. Bailey believed birding should be an intimate relationship, not a distant pursuit.

- It is tough: Living in high-altitude snows, it is resilient. Bailey herself was known for trekking through the Rockies and Sierra Nevada in heavy Victorian skirts, refusing to let societal expectations of “frailty” stop her work.

Summary of the Connection

| Feature | Details |

| Bird | Bailey’s Mountain Chickadee (Poecile gambeli baileyae) |

| Region | Mountains of Southern California & Northern Baja. |

| Named By | Joseph Grinnell (1908). |

| Significance | Honors her work on the Handbook of Birds of the Western US. |

| Her View | She viewed them as the “friendly spirits” of the mountains. |

Florence Bailey: Pinyon Jay (Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus) 🌲

Pinyon jay

(Wiki Image By David Menke – Cropped from: This image originates from the National Digital Library of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service at this page. This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A standard copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing.See Category:Images from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=307353)

Florence Merriam Bailey’s relationship with the Pinyon Jay (Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus) highlights her role as a pioneer of ethology (the study of animal behavior). While male ornithologists of her era were often content to shoot a bird, skin it, and measure its beak, Bailey was interested in the “personality” of the flock.

Here is the story behind the bird she often associated with the “Blue Crows” of the Southwest.

- The “Blue Crow” Personality (🌲)

The pine tree emoji is essential here because this bird is inseparable from the Pinyon Pine forests of the American West.

- The Nickname: Bailey frequently noted the Pinyon Jay’s resemblance to a crow, not just in biology (they are corvids) but in attitude. She described them as having a “crow-like stride” and an intelligent, raucous social structure.

- The “Town Meeting”: In her field notes, she often described their movement not as a migration, but as a “procession.” She observed them descending upon pine cones in “straggling flocks,” chattering constantly in a way that sounded like a chaotic town meeting.

- The Masterpiece: Birds of New Mexico

The Pinyon Jay is a central character in her magnum opus, Birds of New Mexico (1928).

- The Brewster Medal: This book was so comprehensive and beautifully written that it made her the first woman to win the Brewster Medal, the highest honor in American ornithology.

- The Description: In the book, she vividly describes the Pinyon Jay’s voice. She noted their high-pitched calls (“queh-queh”) and their ability to strip pine nuts with terrifying efficiency. She captured the “spirit” of the New Mexican landscape through this bird, describing how they would “surge” through the trees in waves of blue.

- A “Birding on a Bronco” Moment

Bailey was famous for conducting her fieldwork while riding a horse (as detailed in her book A-Birding on a Bronco), which enabled her to follow wide-ranging flocks such as the Pinyon Jay.

- The Observation: Unlike the shy warblers of the East, Pinyon Jays are bold. Bailey documented how they would approach camps fearlessly to scavenge, allowing her to observe their complex social hierarchies up close without trapping them.

- Conservation Legacy

Bailey was an early advocate of the view that birds were beneficial to ecosystems. She recognized the Pinyon Jay as a forest planter.

- The Planter: She noted that by burying pine nuts (caching them for winter) and forgetting some, the Jays were effectively cultivating the very forests they lived in.

Would you like to learn about her brother, C. Hart Merriam, who founded the U.S. Biological Survey (and likely helped her enter the field), or perhaps the “Opera Glass” movement she initiated to discourage the shooting of birds for identification?

Florence Bailey: American Eared Grebe (Podiceps nigricollis californicus) 🦢

Subspecies nigricollis, adult breeding plumage.

(Wiki Image By Andreas Trepte – Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=33521634)

Florence Merriam Bailey’s relationship with the American Eared Grebe (now simply the Eared Grebe, Podiceps nigricollis) showcases her talent for describing the “personality” of waterbirds. While many ornithologists of her time focused on measurements, Bailey focused on the comedy and tragedy of their daily lives.

Here is the story behind the bird she saw as a master of the water but a fool on land.

- The “Helpless” Traveler (🦢)

The swan emoji you used is ironic because, unlike the graceful swan that can walk on land, Bailey described the Eared Grebe as totally incompetent outside the water.

- The Observation: In Birds of New Mexico, she wrote that this bird is “almost helpless on land.” Because its legs are set so far back on its body (perfect for diving, terrible for walking), she noted that it couldn’t take flight from the ground.

- The “Trap”: She observed that if an Eared Grebe landed in a small pool or on wet ground by mistake, it was effectively trapped, unable to run fast enough to generate lift. She described them as “prisoners” of their own anatomy until they could reach open water.

- The “Floating Cities”

Bailey was fascinated by the chaotic, colonial nature of their nesting grounds in the prairie potholes of the West.

- The Nests: She described their nests not as solid structures but as “floating rafts” of sodden waterweeds. She marveled at how these soggy platforms, often anchored to reeds in the middle of lakes, managed to keep the eggs warm and dry enough to hatch.

- The Noise: Much like her “Blue Crows” (Pinyon Jays), she noted that Eared Grebe colonies were incredibly noisy. The birds were constantly shrieking and splashing, creating a bustling “city” on the water that could be heard from far away.

- The “Disappearing” Trick

Bailey’s “Opera Glass” method of birding was well-suited to grebes because they vanish instantly when threatened.

- The Magic Act: She wrote about their uncanny ability to sink like a submarine. Instead of diving forward with a splash, the Eared Grebe could compress its feathers to release air and slowly submerge backward until only its beak and eyes were visible above the surface—a behavior she found both amusing and practical.

- A “Golden” Portrait

The “Eared” part of the name comes from the golden fan of feathers behind the eye during breeding season. Bailey’s descriptions (and the illustrations by Louis Agassiz Fuertes in her books) highlighted this flair.

- The Look: She described the breeding plumage as striking: a black head with “golden ear-tufts” that fanned out when the bird was excited or courting, giving it a look of intense, wild alertness.

Would you like to learn about the “Grebe’s Dance” (the rushing ceremony) that she likely observed, or perhaps her work with the Dipper (Water Ouzel), another bird that uniquely masters the water?

Florence Bailey: Western Tanager (Piranga ludoviciana) 🌈

Western Tanager (Male), Piranga ludoviciana, Cabin Lake Viewing Blinds, Deschutes National Forest, Near Fort Rock, Oregon

(Wiki Image By http://www.naturespicsonline.com/ – http://www.naturespicsonline.com/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=973994)

Florence Merriam Bailey’s relationship with the Western Tanager (Piranga ludoviciana) exemplifies her “quiet” method of birding. While her male contemporaries were often shooting these bright birds to add them to museum collections, Bailey was coaxing them out of bushes with a whistle to study their “winsome” personalities.

Here is the story behind the bird that brought a splash of tropical color to her western travels.

- The “Winsome” Encounter (🌈)

The rainbow emoji is fitting for a bird with a bright red head, yellow body, and black wings. Bailey’s most famous interaction with this species occurred when she was 66 years old, hiking in the Grand Canyon.

- The Whistle: She spotted a currant bush and made a low, coaxing sound she described as “pit-r-ick, pit-r-ick.”

- The Response: In response to her call, an immature Western Tanager (with a “yellowish-green head”) popped out of the bush. It was holding a berry in its beak.

- The Personality: Instead of flying away, the young bird hopped onto a fence within arm’s reach of her. She wrote that it had a head tilt that gave it a look of “winsome trustfulness,” a phrase that perfectly captures her empathetic approach to ornithology.

- The “Louisiana” Connection

In Bailey’s time, this bird was often referred to in her books (e.g., the Handbook of Birds of the Western United States) as the Louisiana Tanager.

- The History: The scientific name ludoviciana means “of Louisiana.” This doesn’t refer to the modern state, but to the vast Louisiana Purchase territory where Lewis and Clark first discovered the bird. Bailey’s writings often bridge this gap between 19th-century exploration and 20th-century conservation.

- A “Tropical” Visitor in the Pines

Bailey was struck by how out of place this bird looked in the rugged coniferous forests of the West.

- The Contrast: In her field notes, she often described the male Western Tanager as a “fragment of the tropics” set against the dark green of the Douglas Firs and Ponderosa Pines. She noted that their brilliant red heads made them look like glowing embers in the deep shade of the forest.

- Birds of New Mexico

In her comprehensive guide, she documented their behavior with her characteristic detail.

- The Diet: She observed them not just as fruit eaters, but as expert flycatchers. She described them darting out from the high pine branches to catch insects in mid-air, a behavior that distinguishes them from many other colorful songbirds.

Would you like to learn about her husband, Vernon Bailey, who was a Chief Naturalist for the Biological Survey and her constant field companion, or the “Verdin,” a tiny desert bird she described as having the spirit of a chickadee?

Florence Bailey: Robin (Turdus migratorius) 🏡

American robin in Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, NY

(Wiki Image By Rhododendrites – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=147440408)

Florence Merriam Bailey’s relationship with the American Robin (Turdus migratorius) is the foundation of her entire philosophy: that birding should be for everyone, right in their own backyard.

Here is the story behind the bird that serves as the “Chapter One” of her legacy.

- The “First” Bird (🏡)

The house emoji is perfect because Robin was literally the starting point of her most famous beginner’s guide, Birds of Village and Field (1898).

- Chapter 1: She placed Robin as the very first entry in the book. She knew that to get people interested in ornithology, she had to start with the bird they saw on their front lawn every morning.

- The “Gateway Drug”: By teaching people to observe the complex behaviors of this “common” bird—how they plaster their nests with mud or listen for worms—she proved that you didn’t need to travel to the Amazon to be a naturalist. You just needed to look out the window.

- East vs. West: A Personality Split

One of Bailey’s keenest observations came from her travels between New York and the American West. She noticed that the Western Robin (T. m. propinquus) was practically a different bird in spirit.

- The Eastern Robin: In the East, she knew them as the “dooryard” friends that hopped happily on manicured lawns.

- The Western Robin: In her Handbook of Birds of the Western United States, she noted that in the wilder parts of the West, the Robin was often a shy, forest-dwelling bird that avoided humans.

- The Change: She documented how, as settlers irrigated the desert and planted lawns in New Mexico and California, the Western Robins slowly “learned” to become the tame, domestic neighbors we know today.

- The “Mud” Architects

Bailey was fascinated by Robin’s masonry skills. In her field notes, she encouraged “opera glass” birders to watch the female Robin building her nest.