John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and Cornelius Vanderbilt: Family Mansions

Of the three Gilded Age tycoons, the Vanderbilt family was the most prolific and ostentatious builder of lavish mansions, creating palaces for social display. Andrew Carnegie built grand, comfortable homes that reflected his “Gospel of Wealth,” while John D. Rockefeller created a solid, art-filled dynastic compound meant to last for generations.

The Vanderbilt Family: Palaces for “American Royalty” 👑

Having inherited the Commodore’s massive fortune, the Vanderbilt heirs, particularly his grandchildren, engaged in a fierce competition to build the most opulent homes in America.

- Famous Mansions: The Breakers and Marble House in Newport, RI; the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, NC.

- Architecture & Style: They favored the Beaux-Arts style, hiring architects like Richard Morris Hunt to design literal palaces in the style of French chateaus and Italian villas. The goal was to project a sense of royalty.

- Purpose: These homes were social weapons, designed to host extravagant balls and solidify the family’s status at the top of society. Their immense cost and imported grandeur were a public declaration of their power.

The Andrew Carnegie Family: Castles for Comfortable Living 🏰

Andrew Carnegie’s homes were built after he had amassed his fortune and were designed to reflect his philosophy of wealth as a public trust.

- Famous Mansions: His New York City Mansion (now the Cooper Hewitt Museum) and Skibo Castle in Scotland.

- Architecture & Style: His homes were grand but less ornate than the Vanderbilts’. The NYC mansion was a stately Georgian Revival home, while Skibo was a sprawling Scottish Baronial estate. They were technologically advanced, featuring innovations like private elevators and central heating.

- Purpose: His mansions were designed as comfortable, functional homes for family, work, and as centers for intellectual life, featuring massive libraries and pipe organs. They were impressive but not built for wasteful extravagance.

The John D. Rockefeller Family: A Compound for a Dynasty 🏛️

John D. Rockefeller, guided by his sober Baptist faith and a belief in permanence, created a secluded family estate rather than a palace for public display.

- Famous Mansion: Kykuit, the main house on the 3,400-acre Rockefeller family estate in Pocantico Hills, NY.

- Architecture & Style: Kykuit is a formidable Classical Revival stone mansion. Its style is solid, elegant, and designed to harmonize with its extensive, art-filled gardens.

- Purpose: Kykuit was a private, multi-generational seat of power. It was built not to compete in society, but to endure for centuries, serving as a home and a private museum for one of the world’s most important art collections.

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions

Kykuit front facade, designed by William Welles Bosworth

(Wiki Image By The original uploader was Daderot at English Wikipedia. – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons by Matthiasb using CommonsHelper., CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6838777)

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions Quotes

The Rockefeller family viewed their grand estates not as lavish palaces for social display, but as serious, multi-generational projects meant to embody a sense of duty, permanence, and a love for art.

Their quotes reveal a family that saw their homes as a profound responsibility, not just a luxury.

John D. Rockefeller Sr.: The Frugal Patriarch

The founder of the dynasty set a tone of sober responsibility. He was famously involved in the running of his estates, personally reviewing household account books to ensure no money was wasted.

“I have always regarded it as a religious duty to get all I could honorably and to give all I could.”

This philosophy—that his fortune was not his to squander—was deeply ingrained in his children and the homes they built.

John D. Rockefeller Jr.: The Dutiful Builder

John D. Rockefeller Jr. was the primary visionary behind Kykuit, the family’s main estate. He saw its creation as a moral and artistic duty, focusing on perfection, harmony with nature, and creating a space that would instill the right values in his children.

His son, Nelson, later summarized his father’s motivation:

“My father’s dream was to create something so beautiful and so perfect that it would be a joy to all who saw it, a place where his family could live and grow and be inspired by the beauty around them.”

Nelson Rockefeller: The Art Steward

As governor of New York and U.S. Vice President, John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s son, Nelson, was a major force in expanding Kykuit’s modern art and sculpture collection. He, more than anyone, articulated the family’s sense of public obligation, eventually bequeathing the estate to the National Trust.

“The ability to create something beautiful, to bring art and nature together, is one of the great privileges of wealth, but it is also a great responsibility.”

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions Chronology Table

John D. Rockefeller’s approach to his homes was a slow, deliberate process of creating a permanent family dynasty, not a “race” to build the most opulent palace. He acquired and developed his properties over decades, with his main estate, Kykuit, reaching its final form long after the Gilded Age’s peak.

Here is a chronological table of his most significant residences.

| Date | Location | Property | Significance |

| 1868 | Cleveland, OH | Euclid Avenue Home | His first primary residence was on Cleveland’s “Millionaires’ Row,” reflecting his rising status with Standard Oil. |

| 1878 | East Cleveland, OH | Forest Hill | Purchase his sprawling 700-acre country estate, which served as his primary home for decades. |

| 1884 | New York, NY | 4 West 54th Street | Establishes a permanent foothold in New York City, the nation’s financial and social center. |

| 1893 | Pocantico Hills, NY | Kykuit (Land Purchase) | Begins acquiring the 3,400 acres that would become the Rockefeller family’s dynastic compound. |

| 1906-1913 | Pocantico Hills, NY | Kykuit (Main House) | Construction of the final, iconic six-story stone mansion created a permanent legacy estate for his family. |

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions YouTube Video

Here are some of the most viewed YouTube videos about the Rockefeller family’s mansions, focusing on their famous Kykuit estate and other homes.

1. Kykuit – The House and Gardens of the Rockefeller Family

- Views: 412,651

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1rxBQbtTL2U

- Description: This is a comprehensive and popular video tour from Historic Hudson Valley, which manages the Kykuit estate. It provides an excellent overview of the main house, the extensive gardens, and the famous sculpture collection.

2. The Homes of Peggy and David Rockefeller

- Views: 110,452

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nO8lMqaFaRU

- Description: Produced by Christie’s auction house, this video offers a rare look inside the personal homes and art collections of David and Peggy Rockefeller, providing insight into the family’s later generations.

3. The Forgotten Rockefeller Mansion: The Eyrie

- Views: 57,381

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VB5Wwz_R7CQ

- Description: This video explores a lesser-known but significant Rockefeller property, offering a glimpse beyond the famous Kykuit estate.

4. The Story of Rockefeller’s Iconic Estate: Kykuit Mansion

- Views: 33,599

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7-lHmbE7v2Q

- Description: A concise video from the channel “This House” that tells the history and story behind the creation of the Kykuit mansion.

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: History

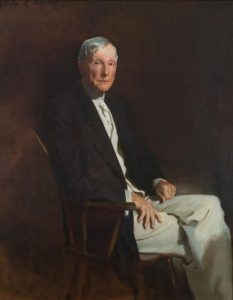

John Singer Sargent – John D. Rockefeller

(Wiki Image By John Singer Sargent – Kykuit, National Trust for Historic Preservation, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=148507642)

Here’s a concise history of John D. Rockefeller’s family mansions, focusing on their creation, purpose, and legacy:

🏛 John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: History

- Forest Hill (Cleveland, Ohio)

- Built: 1860s (as a Rockefeller family summer estate)

- Role: Served as Rockefeller’s primary retreat during his years in Cleveland, close to Standard Oil headquarters.

- Legacy: The estate was later destroyed by fire in 1917. The land was eventually transformed into Forest Hill Park, a public space donated by the Rockefeller family.

- 4 West 54th Street Mansion (New York City)

- Built: 1884

- Architect: George B. Post

- Style: Brownstone, reflecting Gilded Age urban opulence.

- Role: Rockefeller’s principal New York City residence, located in Midtown Manhattan near Fifth Avenue.

- Legacy: After Rockefeller’s passing, the home was converted into the Museum of Modern Art’s first location in 1929, under the patronage of his son, John D. Rockefeller Jr.

- Kykuit (Sleepy Hollow, New York)

- Built: 1908

- Architect: William Welles Bosworth

- Style: Classical Revival mansion set on a hill overlooking the Hudson River.

- Role: Commissioned by John D. Rockefeller Sr. but mainly completed by his son, John D. Rockefeller Jr., as a family seat.

- Features: Lavish gardens, fountains, and later, extensive modern art collections (assembled by Nelson A. Rockefeller).

- Legacy: Kykuit remains the most famous Rockefeller family home, today preserved and open to the public through the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

- Pocantico Hills Estate (Hudson Valley, New York)

- Role: Not a single mansion but an expansive family estate surrounding Kykuit.

- Use: The Rockefeller family used this as a communal retreat and working estate, emphasizing land conservation and farming.

- Legacy: Portions of the estate were gifted as parkland and cultural sites, including the Rockefeller State Park Preserve.

📜 Themes in History

- Philanthropy and Public Use: Many Rockefeller properties transitioned into public institutions (parks, museums, preserves).

- Family Legacy: The mansions were built not just for luxury, but to cement family unity and cultural influence.

- Architectural Evolution: From modest urban brownstones to sprawling Hudson Valley estates, the homes reflected the family’s rising stature.

Would you like me to create a timeline chart showing the development of Rockefeller’s mansions alongside significant events in his business and philanthropic life? That would provide you with a precise historical context.

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: Humanity

Laura Spelman Rockefeller, Mrs John D. Rockefeller

(Wiki Image By James Jebusa Shannon – Kykuit, National Trust for Historic Preservation, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=148507907)

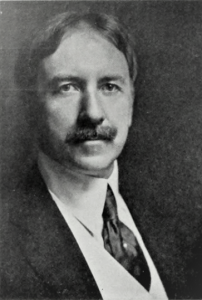

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: Advisors, The Guiding Hands Behind the Rockefeller Family’s Architectural Legacy

A portrait of William W. Bosworth, from page 102 of The Brickbuilder volume 24.

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – The BrickBuilder (1915), volume 4. https://archive.org/details/brickbuild24unse, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38172901)

The creation of the Rockefeller family’s iconic mansions, symbols of a fortune built on oil and philanthropy, was not the work of a single mind but rather a collaborative effort involving a cadre of trusted architects, designers, and advisors. These individuals were instrumental in translating the family’s vision of understated elegance, practicality, and a deep appreciation for art and nature into enduring architectural statements.

Kykuit: A Symphony of Talent

The crown jewel of the Rockefeller estates, Kykuit, the six-story stone house overlooking the Hudson River in Pocantico Hills, New York, exemplifies this collaborative approach. The primary advisors for this landmark mansion were:

- Delano & Aldrich: The architectural firm of William Adams Delano and Chester Holmes Aldrich was selected by John D. Rockefeller Jr. to design Kykuit. They were tasked with creating a home that was grand yet not ostentatious, reflecting the family’s Baptist sensibilities. The resulting Beaux-Arts design is a testament to their ability to balance classical proportions with a sense of comfortable domesticity.

- William Welles Bosworth: A graduate of the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Bosworth was the landscape architect for Kykuit. He was responsible for the stunning terraced gardens, fountains, and pavilions that surround the house, seamlessly integrating the formal architecture with the natural beauty of the Hudson Valley. His design for the grounds is considered a masterpiece of early 20th-century landscape architecture. (Bosworth designed the Cambridge campus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, including Building 10 and the Great Dome.)

- Ogden Codman Jr.: A prominent interior designer and co-author of the influential book The Decoration of Houses with Edith Wharton, Codman was brought in to advise on the interior decoration of Kykuit. He championed a style of classical simplicity and order, moving away from the heavy, cluttered interiors of the Victorian era. His influence can be seen in the elegant and harmonious spaces within the mansion.

- Abby Aldrich Rockefeller: The wife of John D. Rockefeller Jr., Abby was a passionate art collector and a woman of refined taste. She served as a key artistic consultant throughout the design and furnishing of Kykuit, and her influence is particularly evident in the integration of art into the home. She was a co-founder of the Museum of Modern Art, and her forward-thinking artistic sensibilities laid the groundwork for the impressive art collection that would later be housed at Kykuit.

Beyond Kykuit: A Network of Expertise

The Rockefeller family’s portfolio of residences extended beyond Kykuit, and for these properties, they relied on other trusted advisors:

- Andrew J. Thomas: In the 1920s, John D. Rockefeller Jr. engaged New York architect Andrew J. Thomas to design the Forest Hill residential development in Cleveland, Ohio, on the site of the family’s former summer home. Thomas was known for his work on humane, well-designed housing.

- Mott B. Schmidt: This architect, known for his elegant Georgian-style houses, was a favorite of the Rockefeller family in the mid-20th century. He designed homes for David and Peggy Rockefeller, as well as for other prominent American families.

The Business and Philanthropic Advisor

While not an architect or designer, Frederick T. Gates played a crucial role as a principal advisor to both John D. Rockefeller Sr. and Jr. on business and philanthropic matters. His influence on the family’s approach to their vast fortune undoubtedly extended to the ethos behind their building projects, emphasizing stewardship, legacy, and a sense of public responsibility.

The Rockefeller family mansions, therefore, are the product of a thoughtful and collaborative process, shaped by a team of skilled professionals who shared the family’s vision of creating homes that were not only beautiful and comfortable but also reflective of their values and their enduring impact on American society.

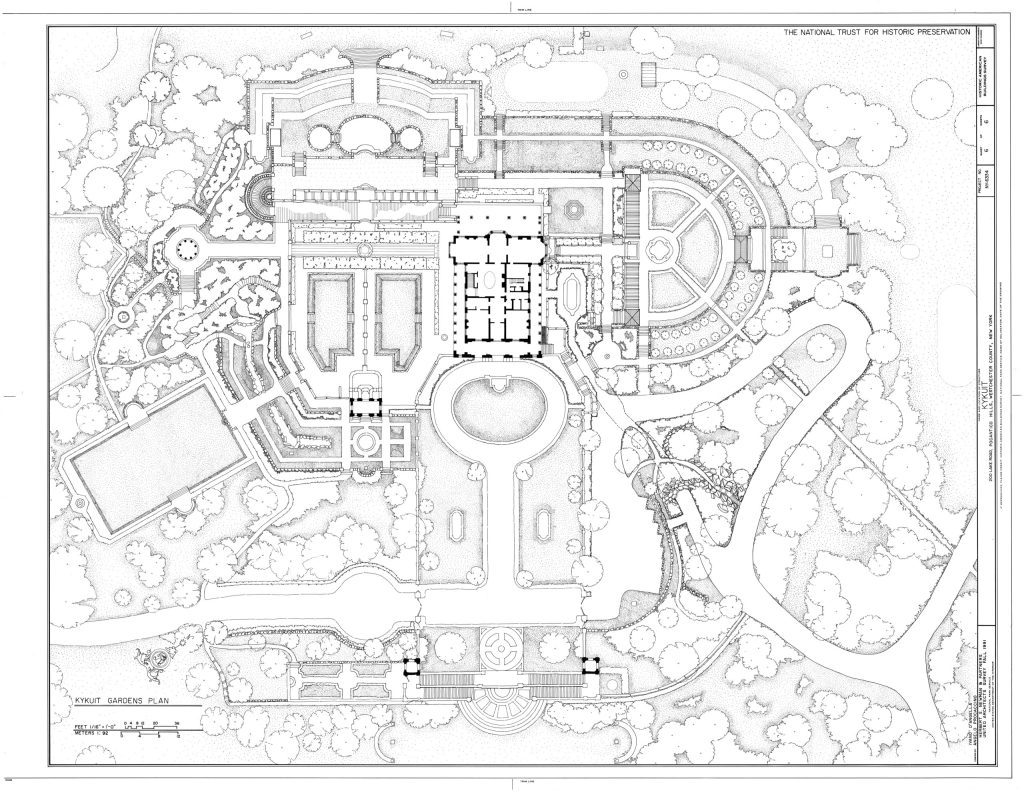

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: Architecture

Kykuit, 200 Lake Road, Pocantico Hills, Westchester County, NY HABS NY,60-POHI,1- (sheet 6 of 6)

(Wiki Image By Related names:Collins, Judy, transmitter – https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ny1715.sheet.00006a, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=34379982)

John D. Rockefeller’s family mansions are distinguished by their diverse architectural styles, reflecting the tastes of different generations of the family. While his early homes were more Victorian, his most famous estate, Kykuit, stands out as a prime example of early 20th-century Classical Revival architecture.

Kykuit: A Classical Revival Masterpiece

Kykuit, located in Pocantico Hills, New York, was initially conceived by John D. Rockefeller and his son, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Completed in 1913, the main house was designed by the firm of Delano & Aldrich. The architectural style is best described as Classical Revival, characterized by its symmetrical design, grand scale, and use of classical elements like columns, porticos, and formal facades.

- Exterior: The four-story villa is constructed from local stone and sits on a terraced hilltop, offering a “lookout” view of the Hudson River, which is how it got its name. Its design was intended to be stately and dignified, avoiding the excessive ornamentation often associated with the Gilded Age.

- Gardens and Landscape: The surrounding grounds were as meticulously planned as the house. Landscape architect William Welles Bosworth designed the formal gardens in a Beaux-Arts style, featuring geometric arrangements, fountains, pavilions, and classical sculptures. The gardens are a key feature of the estate, serving as an outdoor extension of the formal architecture.

- Interior and Art: The interiors, designed by Ogden Codman Jr., reflect an 18th-century European style. However, the estate’s art collection, amassed by later generations like Nelson A. Rockefeller, created a striking contrast. Modern and abstract sculptures by artists like Henry Moore and Pablo Picasso were placed throughout the classical gardens, creating a unique juxtaposition of traditional and contemporary art.

Other Family Homes

While Kykuit is the most well-known, other Rockefeller properties showcase a variety of architectural styles:

- Forest Hill: Rockefeller’s summer estate in Cleveland was a large Victorian mansion that was later replaced with a residential development featuring French Norman-style houses, a project led by his son, John D. Rockefeller Jr.

- Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller Mansion: This Woodstock, Vermont, property, which later became part of the Rockefeller family’s holdings, had been transformed over time. Originally a Federal-style home, it was later renovated into a fashionable Stick Style and then a Queen Anne-style mansion, showcasing intricate brickwork and decorative trim.

The architectural legacy of the Rockefeller family is a reflection of their evolving tastes, from the high Victorian to the clean lines of Classical Revival, and the later embrace of modern art and design.

The following video provides an inside look at the lost Rockefeller mansions. Inside the LOST Rockefeller MANSIONS

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: Art

The art collections within the Rockefeller family’s mansions are a testament to a multi-generational passion for art that evolved from traditional tastes to a pioneering embrace of modern and abstract works. The collection is not a single entity, but rather a reflection of the individual tastes and philanthropic spirit of different family members, with the magnificent Kykuit estate serving as the primary showcase.

The Foundation: John D. Rockefeller Jr. and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller

While John D. Rockefeller Sr.’s tastes were more conventional, the true genesis of the family’s significant art collection began with his son, John D. Rockefeller Jr., and especially his wife, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller.

- John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s Collection: His taste leaned towards the classical and traditional. He had a fondness for Chinese and European ceramics, wonderful porcelain, as well as 18th-century English and French prints. He was also a patron of portraiture, commissioning works by noted artists like John Singer Sargent.

- Abby Aldrich Rockefeller’s Visionary Collection: Abby was a trailblazer in her appreciation for modern and folk art, forms that were not widely accepted in elite collecting circles at the time.

- Modern Art: She was a driving force behind the founding of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City. Her collection included works by European modern masters, which formed the nucleus of MoMA’s collection.

- American Folk Art: Abby was one of the first major collectors of American folk art, seeing its artistic merit long before it was widely recognized. Her extensive collection of paintings, sculptures, and decorative arts from the 18th and 19th centuries became the basis for the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in Colonial Williamsburg.

The Modernist Expansion: Nelson A. Rockefeller

The next generation, particularly Nelson A. Rockefeller, dramatically expanded the family’s collection, bringing a bold, modern sensibility to Kykuit. As governor of New York and later Vice President, Nelson was a passionate and knowledgeable collector, and he transformed the estate into a world-class gallery of 20th-century art.

- The Sculpture Gardens: Nelson’s most significant contribution to Kykuit’s art collection is the extraordinary outdoor sculpture garden. He populated the estate’s magnificent grounds with over 70 works by modern masters, including:

- Henry Moore

- Alexander Calder

- David Smith

- Louise Nevelson

- Aristide Maillol

- Constantin Brancusi

- Alberto Giacometti

- The Underground Art Galleries: Nelson converted the basement passages of Kykuit into a private art gallery to house his impressive collection of paintings and tapestries. This subterranean gallery features works by:

- Pablo Picasso: A series of tapestries designed by Picasso was commissioned by Nelson.

- Andy Warhol

- Marc Chagall

A Continuing Legacy: Peggy and David Rockefeller

David Rockefeller, Nelson’s brother, and his wife Peggy also amassed a significant art collection, which was housed in their various homes, including Hudson Pines on the Pocantico estate. Their collection was notable for its exceptional quality and breadth, encompassing:

- Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Masterpieces: They had a remarkable collection of paintings by artists such as Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, and Henri Matisse.

- American Painting: Their collection also included important works by American artists.

- Decorative Arts: Like the generations before them, David and Peggy had a keen eye for decorative arts, including English and European furniture and an extensive collection of porcelain.

Upon their deaths, the collection of Peggy and David Rockefeller was auctioned at Christie’s, with the proceeds benefiting several philanthropic causes, continuing the family’s long tradition of using their wealth and their passion for art to support the public good.

In essence, the art of the Rockefeller family mansions is a journey through the history of art collecting in the 20th century, from a foundation in classical and traditional art to a groundbreaking embrace of modernism, all set against the stunning backdrop of their magnificent homes.

You can learn more about the art collection and its history in this video. Art This Week-San Antonio Museum of Art-Nelson Rockefeller’s Picassos

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: Family

The White House released the official photograph of Vice President Nelson Rockefeller.

(Wiki Image By White House – White House, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=426909)

The Rockefeller family’s mansions, mainly their ancestral home, Kykuit, served as the multigenerational center for one of America’s most influential dynasties. The family that inhabited these homes was shaped by a powerful patriarch, a visionary matriarch, and a generation of sons who would each leave their mark on the world.

The Founding Generations

The culture and legacy of the Rockefeller homes were established by its first two generations, who balanced immense wealth with a strong sense of duty and a relatively private family life.

- John D. Rockefeller Sr. (1839-1937): The patriarch of the family and the founder of the Standard Oil Company, “Senior” envisioned the Pocantico Hills estate as a private, secure retreat from the pressures of the public eye. While he oversaw the initial construction, his taste was for the practical and the natural, with a preference for enjoying the landscape, road-building, and outdoor pursuits.

- John D. Rockefeller Jr. (1874-1960): Known as “Junior,” he was the actual builder of Kykuit as it stands today. As the only son, he was tasked with managing the family’s fortune and transforming it into a force for global philanthropy. A reserved and deeply moral man, he ran the household with a sense of order and purpose.

- Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (1874-1948): The wife of John D. Jr., Abby was the heart of the family. A discerning art collector and a co-founder of the Museum of Modern Art, she brought a warmth, aesthetic sensibility, and a forward-thinking cultural perspective to the home. She was a central and beloved figure in the lives of her children.

The Third Generation: “The Brothers”

John D. Jr. and Abby raised six children, including one daughter, Abby “Babs” Rockefeller Mauzé, and five sons who became collectively known as “The Brothers.” They grew up between their home in New York City and the Pocantico estate, and their lives were shaped by the values of philanthropy, business, and public service instilled there.

- John D. Rockefeller 3rd (1906-1978): The eldest son, he was a thoughtful philanthropist with a focus on Asia and the arts, founding the Asia Society and the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts.

- Nelson A. Rockefeller (1908-1979): The most public of the brothers, Nelson was a four-term Governor of New York and later served as Vice President of the United States. He eventually became the final resident of Kykuit, filling its rooms and grounds with his vast modern art collection.

- Laurance S. Rockefeller (1910-2004): A venture capitalist and dedicated conservationist, Laurance was instrumental in establishing and expanding national parks across the country.

- Winthrop Rockefeller (1912-1973): He moved to Arkansas, where he served two terms as governor, focusing on economic development and civil rights.

- David Rockefeller (1915-2017): The youngest brother, he was a prominent banker who served as chairman and CEO of Chase Manhattan Bank and became a leading figure in global finance and philanthropy.

These brothers, although they had their own homes, always considered the Pocantico estate the center of their family’s gravity. They held regular family meetings to discuss their shared philanthropic and business ventures, continuing the legacy of stewardship that began with their grandfather in the stately rooms of Kykuit.

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: Food

Kykuit’s dining room

(Wiki Image By Ɱ – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=64966704)

The food culture in John D. Rockefeller’s family mansions reflected the family’s core values: moderation, simplicity, and a focus on health. Despite their immense wealth, dining at the Rockefeller table was not an affair of Gilded Age extravagance. The focus was on wholesome, fresh food, often sourced directly from their estate, and a disciplined approach to eating that John D. Rockefeller Sr. believed was key to his longevity.

A Diet of Simplicity and Health

John D. Rockefeller Sr. was famously health-conscious and adhered to a plain diet for much of his adult life. Having suffered from digestive ailments, he prioritized simple, easily digestible foods. This set the tone for the entire household.

A typical meal might consist of milk, bread, and a simple vegetable or fruit. While the fare for the rest of the family and guests was more varied, it was never ostentatious. Menus emphasized quality and freshness over complexity. The family’s Baptist faith also influenced their lifestyle, leading them to abstain from alcohol, a practice that was a notable contrast to many of their high-society peers.

From Estate to Table 🧑🌾

The Rockefeller estate at Pocantico Hills was a fully functioning agricultural operation, designed to be largely self-sufficient. This farm-to-table approach was central to the family’s dining experience long before it became a modern culinary trend.

The estate included:

- A large vegetable garden that supplied the kitchens with fresh produce.

- Orchards that provided a variety of fruits.

- A dairy farm with a herd of Jersey cows, ensuring a constant supply of fresh milk, cream, and butter.

This control over their food source guaranteed the quality and freshness that the family valued. The kitchens were run by a professional staff who were skilled in preparing the simple, American-style cuisine favored by the Rockefellers.

Entertaining and Later Generations

While daily meals were simple, the Rockefellers did entertain guests, including world leaders and influential figures. On these occasions, the menus would be more elaborate, but still in keeping with the family’s preference for understated elegance.

Later generations, particularly Nelson Rockefeller, brought a more modern and cosmopolitan approach to entertaining at Kykuit. However, the foundational culture of health-conscious, high-quality, and unpretentious food remained a hallmark of life in the Rockefeller family mansions.

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: Garages

Kykuit Rockefeller garage and carriage house

(Wiki Image By Shinya Suzuki from New York, U.S.A. – KYKUIT The Rockefeller Estate, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=57451385)

The garages at John D. Rockefeller’s family mansions were not just places to store cars; they were grand, multi-purpose buildings that evolved from coach barns to house the newest technology of the automotive age.

The Coach Barn at Kykuit

The most famous of these structures is the Coach Barn at the Rockefeller family’s Kykuit estate in Pocantico Hills, New York. Initially built in 1902 to house horse-drawn carriages, it was later renovated and expanded to accommodate the family’s growing fleet of automobiles.

- Architecture: The Coach Barn is a massive, three-story building constructed of rough-faced, dark gray granite. Its architectural style is a blend of traditional coach barn design and the more modern needs of an automobile garage. It is an impressive building, even larger in ground area than the main house itself. The only decorative element is a clock tower with chimes.

- Multi-Purpose Use: The Coach Barn was a hub of activity. In addition to a garage and a carriage room, it housed a mechanic shop, a boiler plant that heated both the barn and the main house, staff apartments, and offices for the estate’s manager.

- Vehicle Collection: The building’s main hall now serves as a museum, displaying the family’s collection of historic carriages and early automobiles. This includes a 1902 Thomas automobile that John D. Rockefeller, Sr. once drove exclusively on the roads he built on his Maine estate.

The Rockefeller garages were a clear example of the family’s embrace of technological progress. They were not an afterthought, but rather an integral and architecturally significant part of the estate’s infrastructure, designed to manage the transition from a horse-drawn to a motor-driven world.

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: Grounds

One of several gardens

(Wiki Image By Ɱ – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=62181722)

Here’s an overview of the grounds surrounding John D. Rockefeller’s family mansions, focusing on their design, purpose, and legacy:

🌳 John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: Grounds

- Forest Hill Estate (Cleveland, Ohio)

- Size: About 700 acres.

- Grounds: Rolling hills, wooded areas, and landscaped gardens. Rockefeller emphasized nature walks and open lawns rather than ornate landscaping.

- Legacy: After a fire destroyed the mansion in 1917, much of the estate was converted into Forest Hill Park, donated to Cleveland and East Cleveland by Rockefeller’s heirs.

- 4 West 54th Street Mansion (New York City)

- Urban Setting: Limited grounds due to its location in Midtown Manhattan.

- Features: Small private garden and carriage house at the rear.

- Legacy: The house’s grounds eventually disappeared into New York’s urban sprawl; the lot is now part of the Museum of Modern Art campus.

- Kykuit Estate (Sleepy Hollow, New York)

- Size: ~3,400 acres (including surrounding Pocantico Hills).

- Design: Formal terraces, stone walls, Italianate gardens, fountains, and sculpture collections. Designed with the help of William Welles Bosworth.

- Highlights:

- Rose gardens, landscaped paths, and classical fountains.

- Panoramic views over the Hudson River.

- Extensive art installations, later expanded by Nelson Rockefeller.

- Legacy: Still the centerpiece of the family estate, preserved with original gardens and artworks.

- Pocantico Hills Grounds (Hudson Valley, NY)

- Size: Thousands of acres surrounding Kykuit.

- Use: A mix of farming, forestry, and conservation. Rockefeller Sr. was deeply interested in land stewardship and agricultural experimentation.

- Features:

- Working farms and orchards.

- Horse trails, carriage paths, and scenic stone bridges.

- Lakes and landscaped woods for recreation.

- Legacy: Portions became Rockefeller State Park Preserve, reflecting the family’s long-standing conservation ethic.

🌿 Key Themes in the Grounds

- Nature & Conservation: Rockefeller Sr. believed in integrating luxury with natural beauty and sustainability.

- Art & Culture: Later generations (especially Nelson Rockefeller) enhanced the grounds with modern sculpture and architecture.

- Public Access: Many Rockefeller lands were eventually donated to the public, blending family legacy with philanthropy.

Would you like me to create a map-style diagram showing how each estate’s grounds were arranged (gardens, terraces, parks, farmland)? That could help you visualize the differences between Rockefeller’s rural and urban homes.

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: Humor and Anger

The humor in John D. Rockefeller’s family mansions was typically dry and understated, often involving gentle pranks and witty remarks. At the same time, expressions of anger were rare and controlled, reflecting the family’s disciplined and reserved nature.

Humor: Dry Wit and Gentle Pranks 😄

The atmosphere in the Rockefeller household was generally serious, guided by piety and a strong work ethic. However, there was a place for a particular brand of quiet humor, mostly driven by the patriarch, John D. Rockefeller Sr.

His humor was known to be:

- Dry and Witty: Rockefeller Sr. had a reputation for his sly wit and enjoyed making droll, understated comments. He often gave out shiny new dimes to children and adults alike, a gesture that was part joke, part lesson in thrift, and part public relations.

- Prankish: He had a playful side and enjoyed simple, harmless pranks. A favored pastime was pulling a chair out from under an unsuspecting guest just as they were about to sit, or engaging in lighthearted games with his grandchildren at Kykuit.

- Self-aware: Rockefeller understood his public image as a ruthless tycoon and sometimes played with it. He would joke about his own frugality and was known to respond to begging letters with a mix of genuine philanthropic consideration and humorous dismissal of the more outlandish requests.

This brand of humor was a private affair, a way to lighten the otherwise formal and purposeful atmosphere of the home. It was a humor of quiet confidence, not loud boisterousness.

Anger: A Controlled Rarity 😠

Outward expressions of anger were exceedingly rare within the Rockefeller family, particularly from John D. Sr. and his son, John D. Jr. Their Baptist faith and personal dispositions favored self-control, discipline, and emotional restraint.

- Subdued Displeasure: Anger was more likely to be expressed as a quiet, firm disapproval rather than a raised voice or a fit of temper. Business rivals and muckraking journalists might face a relentless and formidable opponent in the boardroom or the press, but this was a calculated, strategic response, not a hot-headed one. At home, disappointment or frustration would be communicated in a controlled and measured manner.

- Emphasis on Harmony: The family culture, especially under the direction of John D. Jr. and his wife Abby, prioritized harmony and polite discourse. Overt conflict was discouraged. Disagreements were expected to be handled rationally and privately.

The near-absence of overt anger was a core part of the family’s identity. They cultivated an environment of order, reason, and emotional discipline, believing that uncontrolled passion was a barrier to both good business and a moral life. The calm, stately halls of their mansions were a reflection of the internal emotional control they so highly prized.

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: Library

Here’s a focused look at John D. Rockefeller’s family mansions and their libraries, emphasizing how they reflected his values and lifestyle:

- Kykuit (Pocantico Hills, New York)

- Primary Family Estate: Built in 1913, Kykuit became the centerpiece of Rockefeller family life.

- Library Room: Contained a refined but practical collection of books, more modest compared to Carnegie’s vast libraries.

- Themes of Collection: Religion (especially Baptist texts), moral philosophy, American history, and business-related works.

- Style: Elegant yet understated — reflecting Rockefeller’s austerity and simplicity, rather than ostentation.

- Rockefeller’s Approach to Books

- Personal Values: Unlike Carnegie, who displayed literature as a cultural marker, Rockefeller’s libraries were built around spiritual guidance and practical wisdom.

- Religious Focus: The Bible was central to his collection, along with religious commentaries. He often read scripture daily.

- Educational Purpose: Books were seen as tools for moral instruction and self-discipline, not luxury.

- Family Use

- Generational Learning: Rockefeller encouraged his children and grandchildren to use the mansion libraries for study.

- Philanthropic Connection: Though he did not endow libraries on the same scale as Carnegie, his funding of the University of Chicago and the Rockefeller Foundation reflected his belief in education and research.

- Comparison to Peers

- Carnegie: Focused on vast, ornate libraries filled with literature, philosophy, and history, reflecting a show of culture.

- Rockefeller: Choose smaller, carefully curated collections emphasizing religion, morality, and practicality.

- Vanderbilt: His libraries were more decorative, often part of the Gilded Age display of wealth.

✅ In short: John D. Rockefeller’s mansion libraries, especially at Kykuit, symbolized his religious devotion, modesty, and practicality — a contrast to Carnegie’s expansive literary pride and Vanderbilt’s decorative collections.

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: Music

Music hall

(Wiki Image By Ɱ – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=64966710)

Music within the John D. Rockefeller family mansions was a reflection of their cultural and philanthropic values, characterized by a blend of private family enjoyment and significant public patronage, rather than lavish Gilded Age-style balls or concerts.

Private Enjoyment and Musical Instruments 🎹

The Rockefeller family appreciated music in their daily lives, and their homes were equipped for musical enjoyment.

- Organs and Pianos: The central musical feature at Kykuit, their main estate, was a large pipe organ. John D. Rockefeller Sr. enjoyed listening to hymns and other simple tunes played on the organ. Pianos were also a staple in their homes, used for family gatherings and personal recreation. John D. Rockefeller Jr. was known to play the violin.

- Family Sing-alongs: In keeping with their close-knit family culture, the Rockefellers would often gather for informal musical evenings and sing-alongs, with hymns being a prominent part of their repertoire, reflecting their devout Baptist faith.

Patronage of Music 🎼

While private musical life was relatively modest, the Rockefeller family’s impact on the broader world of music was immense. Their philanthropic support for musical institutions was a core part of their cultural legacy. Key examples include:

- Juilliard School: The Rockefeller family’s financial support was instrumental in the development and growth of this world-renowned conservatory for music, dance, and drama.

- Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts: John D. Rockefeller 3rd was a driving force behind the creation of Lincoln Center, which became a significant hub for classical music and opera in New York City.

- Spelman College: The family’s financial contributions to Spelman, a historically Black college for women, helped support its esteemed music department.

This patronage demonstrates that for the Rockefellers, music was not just a source of private pleasure but a vital part of public culture that deserved significant investment and support. The music in their homes was a quiet reflection of a much larger commitment to the arts.

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: Passion

Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York City, c. 1912

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – Popular Science Monthly Volume 80, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20034464)

The defining passions of the Rockefeller family, which profoundly shaped the culture and purpose of their mansions, were philanthropy, art, and nature.

Philanthropy: A Moral Obligation 🌍

The foremost passion that animated the Rockefeller family was a deeply ingrained sense of philanthropic duty. This was not a hobby but the central organizing principle of their lives. John D. Rockefeller Sr., guided by his Baptist faith and advisors like Frederick T. Gates, believed his vast fortune was a public trust. His son, John D. Rockefeller Jr., dedicated his life to transforming this wealth into enduring institutions that would benefit humanity.

Their home, Kykuit, was less a palace for social entertainment and more a headquarters for this global mission. From his office there, Rockefeller Jr. oversaw the creation and funding of entities like the Rockefeller Foundation, the University of Chicago, and Colonial Williamsburg. This passion for strategic, large-scale giving was the family’s most significant legacy and the primary activity that the mansions were designed to support.

Art: A Modern Vision 🎨

A passion for art, particularly modern and folk art, was brought into the family by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. Her visionary taste was a driving force behind the founding of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). She saw art as a vital part of public life and a source of personal inspiration.

This passion was amplified by her son, Nelson A. Rockefeller. He was an avid and voracious collector of modern art, and he transformed the stately grounds of Kykuit into a world-class outdoor sculpture garden. He filled the home’s galleries with works by Picasso, Warhol, and Chagall, creating a unique environment where a historic family seat became a vibrant showcase for 20th-century creativity.

Nature and Conservation 🌳

From the beginning, John D. Rockefeller Sr. had a passion for the land itself. He loved shaping the landscape of his Pocantico Hills estate, designing and building miles of carriage roads to better enjoy the natural beauty of the Hudson Valley.

This love for nature evolved into a profound commitment to conservation, led by John D. Rockefeller Jr. and his son Laurance S. Rockefeller. They were instrumental in the creation and expansion of numerous U.S. National Parks, including Grand Teton, Acadia, and Virgin Islands National Parks. They believed that pristine natural landscapes were a national treasure to be preserved for the public. This passion for the outdoors was a constant in their lives, and their mansions served as private sanctuaries from which they could launch these monumental public conservation efforts.

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: Religion

The Euclid Avenue Baptist Church and its pastor, the Rev. Dr. Charles Aubrey Eaton, in 1904

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn88085187/1904-05-12/ed-1/seq-4/ (The Tacoma Times), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=48595319)

The religion practiced by the Rockefeller family, a devout and committed Northern Baptist faith, was the central pillar of their lives and the primary influence on the culture within their mansions.

A Foundation of Faith and Morality 🙏

From the patriarch, John D. Rockefeller Sr., down through the generations, the family’s life was guided by a strong sense of Protestant Christian morality. This was not a faith reserved for Sunday mornings; it was a comprehensive worldview that shaped their daily routines, their business ethics, and their understanding of their immense wealth.

The family’s religious convictions were instilled by John D. Sr.’s mother, Eliza, a devout Baptist who taught him the principles of frugality, discipline, and charity. This manifested in a lifestyle at their homes, including the grand Kykuit estate, that was notably free of the Gilded Age excesses of their peers. The family abstained from alcohol and smoking, and their social life was centered on family, church, and philanthropic pursuits rather than lavish balls.

The “Gospel of Wealth”

John D. Rockefeller Sr.’s faith was the direct source of his revolutionary approach to philanthropy. He was a firm believer in what his contemporary Andrew Carnegie called the “Gospel of Wealth”—the idea that wealth was a trust from God, and the wealthy had a moral obligation to use it for the public good.

This belief animated the purpose of their family mansions. The homes were not primarily places of leisure but command centers for a global philanthropic enterprise. John D. Rockefeller Jr., in particular, dedicated his life to this mission, working from his office at Kykuit to establish and oversee the vast network of foundations and institutions that the family’s fortune funded. He viewed this work as a direct extension of his Christian duty.

Religious Patronage

Beyond their secular philanthropies, the Rockefellers were also significant patrons of Baptist and other Christian institutions. They provided considerable funding for the University of Chicago (initially a Baptist institution), the Riverside Church in New York City, and numerous other churches and religious organizations. This patronage was a direct reflection of a faith that was nurtured and practiced within the quiet, disciplined, and purposeful environment of their family homes.

John D. Rockefeller’s Family Mansions: Servants

A large and meticulously organized domestic staff was essential to the operation of John D. Rockefeller’s family mansions, ensuring the seamless daily life and management of the vast estates, particularly their primary home, Kykuit, at the Pocantico Hills estate.

The Scale of Service

At the height of its operation in the early to mid-20th century, the Pocantico Hills estate employed hundreds of people. This workforce was divided between those who managed the extensive grounds and those who served the family directly within the mansion. At Kykuit, the household staff was a significant, albeit discreet, presence. While the Rockefellers’ lifestyle was less ostentatious than some of their Gilded Age contemporaries, the sheer size and complexity of their homes required a substantial team.

Roles and Hierarchy

The domestic staff was organized in a traditional hierarchical structure, similar to those found in European grand houses. Key roles within the main house included:

- Butler: The head of the male staff, responsible for overseeing the dining room, wine cellar, and pantry. He would supervise the footmen and other male servants.

- Housekeeper: The head of the female staff, responsible for the overall cleanliness and maintenance of the mansion’s many rooms. She managed the housemaids, parlor maids, and laundresses.

- Cook/Chef: In charge of the kitchen and all meal preparation for the family and staff. Given the family’s preference for simple, wholesome food, the cook’s focus was on quality and freshness, often utilizing produce from the estate’s farms.

- Valet: John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s attendant, responsible for his wardrobe and personal needs.

- Lady’s Maid: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller’s attendant, assisting with her clothing, hair, and personal effects.

- Housemaids and Parlor Maids: Responsible for the daily cleaning, dusting, and upkeep of the mansion’s rooms.

- Laundresses: Tasked with washing and pressing the family’s linens and clothing.

- Footmen: Assisted the butler with serving meals and other duties around the house.

Beyond the main house, a vast team of gardeners, groundskeepers, farmhands, and mechanics maintained the thousands of acres of gardens, lawns, roads, and the estate’s self-sufficient farm.

Relationship with the Family

The relationship between the Rockefeller family and their staff was generally one of professional respect and long-term loyalty. In line with their business practices, the Rockefellers were known to be fair employers who provided good wages, secure employment, and benefits like pensions, which was not always standard practice in the era.

The family, notably John D. Rockefeller Jr. and his wife Abby, valued privacy and discretion. While they depended on their staff for the smooth running of their household, there was a clear and formal boundary between the family’s life and the work of the servants. The design of the mansions themselves, with their separate service wings, back staircases, and dedicated staff quarters, reflected this desire to keep the mechanics of the household out of sight. Many staff members served the family for decades, with employment often passing down through generations of the same local families.

Andrew Carnegie’s Family Mansions

The Andrew Carnegie Mansion is a historic house and a museum building at 2 East 91st Street, along the east side of Fifth Avenue, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City.

(Wiki Image By Ajay Suresh from New York, NY, USA – Cooper Hewitt, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=79681136)

Aerial view of Skibo Castle in 2013

(Wiki Image By Graeme Smith, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=66501392)

Andrew Carnegie’s Family Mansions Quotes

The quotes from Andrew Carnegie and his family about their mansions reflect his “Gospel of Wealth” philosophy. They viewed their grand homes not as palaces for social competition, but as centers for family life, comfort, and, in the case of Skibo Castle, a personal paradise on Earth.

Andrew Carnegie: The Proud but Principled Owner

Carnegie often described his homes with a mix of pride and a touch of his characteristic “humble” justification. He referred to his grand New York City mansion as the “modestest, most homelike” on Fifth Avenue, emphasizing its comfort over its size.

But his heart was truly at his Scottish estate, Skibo Castle, which he considered a reward for a life of hard work.

“Heaven is a home like Skibo.”

For him, Skibo was not just a mansion but a retreat where he could live out his dream of being a Scottish laird, surrounded by friends, family, and the beauty of his homeland.

Louise Whitfield Carnegie: The Homemaker

Carnegie’s wife, Louise, was the quiet force who transformed these immense houses into genuine homes. While she oversaw the management of a staff of nearly 100 at Skibo, her focus was always on creating a private, dignified, and loving environment for her husband and daughter.

A biographer noted her philosophy was that, despite the grandeur, the homes should always be a “place of peace and affection,” a sanctuary from the pressures of public life.

Margaret Carnegie Miller: The Daughter

Growing up in these grand residences, Carnegie’s only daughter, Margaret, remembered them not for their opulence but for the family moments they contained. She saw past the stone and steel to the father she adored.

Recalling her time at Skibo, she wrote:

“At Skibo, my father was not a great man… he was a playmate.”

This simple sentiment captures the essence of the Carnegie family’s view: their mansions were ultimately just the backdrop for a close and loving family.

Andrew Carnegie’s Family Mansions Chronology Table

Andrew Carnegie’s residences chronicle his incredible “rags-to-riches” journey, from a humble weaver’s cottage to grand estates that were personal statements of his success and his “Gospel of Wealth” philosophy.

Here is a chronological table of his most significant family homes.

| Date | Location | Property | Significance |

| 1835 | Dunfermline, Scotland | Weaver’s Cottage | Carnegie was born into a small, modest cottage, the son of a handloom weaver. |

| 1880s | Pittsburgh, PA | “Homewood” Estate | His first major estate, purchased for his mother, signaled his arrival as a powerful industrialist in the heart of steel country. |

| 1897 | New York, NY | Fifth Avenue Plot | Purchases land “far uptown” on Fifth Avenue to build his final American home, intentionally away from the more ostentatious mansions of his peers. |

| 1898 | Sutherland, Scotland | Skibo Castle | Purchases his dream estate in his native Scotland and begins a massive, multi-year renovation to create his paradise. |

| 1902 | New York, NY | NYC Mansion | The 64-room stately home (now the Cooper Hewitt museum) is completed, reflecting his status as well as his philosophy of comfortable, functional living. |

Andrew Carnegie’s Family Mansions YouTube Video

Here are some of the most popular YouTube videos showcasing Andrew Carnegie’s family mansions, along with their view counts and links.

1. Inside Andrew Carnegie’s Manhattan Mega Mansion

- Views: 172,818

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FPTrMXNwFXw

- Description: This video from the popular channel “This House” provides a detailed tour and history of Carnegie’s New York City home on Fifth Avenue, which is now the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

2. Inside The Carnegie Family’s “Old Money” Mansions

- Views: 24,377

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CK82t5cAIpQ

- Description: A comprehensive video that explores not only the New York mansion but also the magnificent Skibo Castle in Scotland and other Carnegie family properties, giving a broader look at their “Old Money” lifestyle.

3. Carnegie Family Island Mansion 1884

-

- Views: 14,518

- Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bqPPB3yvboY

- Description: This video focuses on another of the Carnegie family’s grand homes, offering a look at a different aspect of their lives outside of the more famous New York and Skibo residences.

Andrew Carnegie’s Family Mansions: History

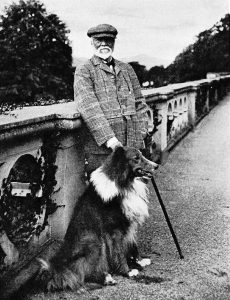

Andrew Carnegie at Skibo, 1914

(Wiki Image Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=887253)

Andrew Carnegie, a name synonymous with the American steel industry and immense wealth, possessed several grand residences. Still, two stand out as his primary family mansions: a stately home in New York City and a sprawling castle in the Scottish Highlands. These opulent dwellings not only served as private family retreats but also as centers for his philanthropic endeavors.

Andrew Carnegie Mansion, New York City

In the heart of Manhattan, at 2 East 91st Street on Fifth Avenue, stands the impressive Andrew Carnegie Mansion. Constructed between 1899 and 1902, this sixty-four-room mansion was designed by the architectural firm of Babb, Cook & Willard. Carnegie’s vision for this residence was clear: he desired “the most modest, plainest, and most roomy house in New York.” While “modest” and “plain” are relative terms for a man of his stature, the Georgian Revival style of the mansion was indeed more restrained than the flamboyant Beaux-Arts palaces favored by many of his contemporaries.

A key feature of the property was its large private garden, a rarity in densely populated Manhattan. The mansion was technologically advanced for its time, boasting a steel frame, a precursor to modern air conditioning, and one of the first residential Otis elevators. This home was the primary residence for Andrew Carnegie, his wife Louise Whitfield Carnegie, and their daughter Margaret. It was from his office in this mansion that Carnegie administered his vast philanthropic efforts, including the funding of thousands of public libraries.

Following Andrew Carnegie’s death in 1919, Louise continued to live in the mansion until she passed away in 1946. The property was then bequeathed to the Carnegie Corporation, and in 1972, it was donated to the Smithsonian Institution. Today, the mansion serves as the home of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, allowing the public to experience the grandeur of Carnegie’s New York City abode.

Skibo Castle, Scotland

In 1898, Andrew Carnegie purchased Skibo Castle, located in the picturesque Scottish Highlands. While a castle had existed on the site for centuries, Carnegie transformed it into a luxurious modern estate. He invested a significant portion of his wealth, an estimated £2 million, to renovate and expand the castle, creating a “heaven on earth” for his family.

The renovation dramatically increased the size of the castle and incorporated modern amenities such as electricity, an indoor swimming pool, and a 9-hole golf course. Skibo became the Carnegie family’s summer retreat, where they would escape the heat of New York City and entertain a wide array of distinguished guests, including King Edward VII.

Despite its grandeur, Skibo was also a place where Carnegie’s philanthropic spirit was evident. He supported the local community and established a pension fund for his workers. The estate remained in the Carnegie family until 1982. Today, Skibo Castle operates as The Carnegie Club, an exclusive private members’ club, preserving the legacy and splendor of Carnegie’s Scottish haven.

Both of these magnificent properties reflect the dual aspects of Andrew Carnegie’s life: his immense success in the world of industry and his profound commitment to philanthropy. They stand as enduring monuments to one of the most influential figures of the Gilded Age.

This video provides a tour of the Carnegie family’s impressive estates. This video offers a tour of the Carnegie family’s remarkable estates. Inside The Carnegie Family’s “Old Money” Mansions

Andrew Carnegie’s Family Mansions: Humanity

Mrs. Andrew Carnegie (Louise Whitfield)

(Wiki Image By Unknown photographer – Carnegie, Andrew (1920) Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie, Houghton Mifflin Co., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=99556969)

Andrew Carnegie’s Family Mansions: Advisors, The Visionaries Behind the Carnegie Mansions: A Blend of Professional Expertise and Personal Direction

Alexander Ross, architect, around 1875

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – Dictionary of Scottish Architects, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=74809079)

Andrew Carnegie’s family mansions, the stately New York City residence on Fifth Avenue, and the sprawling Skibo Castle in the Scottish Highlands were the product of a collaborative effort between the industrialist’s distinct personal vision and the expertise of leading architects, designers, and artisans of his time. While Carnegie employed top professionals, he was no passive client; his philosophies on simplicity, comfort, and functionality heavily influenced the final designs.

The Andrew Carnegie Mansion, New York City: “The Most Modest, Plainest, and Most Roomy House”

For his New York City home, completed in 1902, Carnegie famously desired not another Gilded Age palace of overt opulence, but a comfortable and spacious family home. His principal advisors in achieving this vision were:

- Architects: Babb, Cook & Willard: This prominent New York architectural firm was selected by Carnegie to design his Fifth Avenue mansion. Known for their versatility, Walter Cook, a classically trained architect, is primarily credited with the mansion’s restrained and dignified Georgian Revival style, which stood in stark contrast to the more flamboyant Beaux-Arts mansions of his peers. The firm successfully translated Carnegie’s desire for a substantial yet unpretentious home into a 64-room residence that prioritized light, air, and family comfort.

- Interior Designer (Teak Room): Lockwood de Forest: An artist and designer associated with the Aesthetic Movement, de Forest was responsible for the distinctive “Teak Room,” which served as a private retreat for Carnegie. De Forest’s expertise in East Indian arts and crafts is evident in the room’s intricately carved teakwood panels and decorative elements, creating a unique and exotic space within the otherwise more traditional mansion.

- Landscape Architect: Richard Schermerhorn, Jr.: Schermerhorn was tasked with designing the expansive private garden, a rare luxury in Manhattan. His design provided a tranquil green space for the family and complemented the mansion’s comfortable, residential feel.

- Artistic Glass: Louis Comfort Tiffany: The elegant glass and bronze canopy that graces the mansion’s entrance was designed by the renowned artist and designer Louis Comfort Tiffany, adding a touch of artistic flair to the otherwise reserved exterior.

Skibo Castle, Scotland: A Highland Paradise Reimagined

In contrast to the relative modesty of his New York home, Skibo Castle in Sutherland, Scotland, was a grander undertaking. After purchasing the estate in 1898, Carnegie embarked on a significant expansion and modernization, transforming it into a luxurious retreat. His key advisors in this endeavor were:

- Architects: Ross & Macbeth: The Inverness-based architectural firm of Alexander Ross and Robert Macbeth was responsible for the extensive renovations and additions to Skibo Castle. They skillfully blended the existing structure with new construction in the Scottish Baronial style, creating the romantic and imposing castle we see today.

- Landscape Architect: Thomas Mawson: A leading landscape architect of the Edwardian era, Mawson was brought in to design the castle’s extensive gardens and grounds. He created a series of formal and informal gardens, terraces, and water features that enhanced the natural beauty of the Highland setting and provided a stunning backdrop for the castle.

- Glasshouse and Pavilion Designers: Mackenzie & Moncur: This Glasgow-based firm, renowned for its horticultural buildings, was commissioned to design and build the impressive glasshouses and the state-of-the-art indoor swimming pavilion at Skibo. Their work added a touch of modern luxury and functionality to the historic estate.

The Ultimate Advisor: Andrew Carnegie Himself

Across both projects, the most significant advisor was Andrew Carnegie himself, often in close consultation with his wife, Louise Whitfield Carnegie. His “Gospel of Wealth” philosophy, which advocated for a life of relative modesty and the use of fortune for the public good, directly informed his architectural choices. For Carnegie, his mansions were not merely displays of wealth, but comfortable family homes and efficient settings for his philanthropic work. His direct involvement ensured that the final products were a true reflection of his personal tastes and values, blending professional craftsmanship with a uniquely Carnegiean vision.

Andrew Carnegie’s Family Mansions: Architecture

The Andrew Carnegie Mansion is the present-day home of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum of Decorative Arts and Design in New York City. The sixty-four-room mansion was built by Andrew Carnegie and his wife, Louise Whitfield Carnegie, who wanted a spacious, comfortable, and light-filled home in which to raise their young daughter, Margaret. The house was also planned as a place where Carnegie, after his retirement in 1901, could oversee the philanthropic projects to which he would dedicate the final decades of his life. From his private office in the mansion, Carnegie donated money to build free public libraries in communities across the country and to the improvement of cultural and educational facilities in Scotland and the United States. The mansion was designed in the Georgian style by the architectural firm of Babb, Cook & Willard, and completed in 1901. The property includes a large private garden, a rarity in Manhattan. The house features numerous innovative elements. It was the first private residence in the U.S. to have a structural steel frame and one of the first in New York to have a residential Otis passenger elevator. The house also had central heating and a precursor to modern air conditioning. The building received landmark status in 1974, and in 1976 reopened as Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution.

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – http://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_sic_9161, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19624122)

Andrew Carnegie, the steel magnate and philanthropist, had a distinct architectural taste that reflected his personal values. He sought a balance between grandeur and practicality, often choosing styles that were stately but more restrained than the extravagant palaces of his Gilded Age peers. His two most famous mansions—one in New York City and one in Scotland—perfectly illustrate this approach.

The Andrew Carnegie Mansion, New York City

Carnegie’s New York residence, now the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, was built from 1899 to 1902. Designed by the firm of Babb, Cook & Willard, the 64-room mansion is a prime example of Georgian Revival architecture.

- Style: The mansion’s design is a modified Georgian eclectic style, featuring a brick and stone facade, symmetrical windows with heavy stone trim, and a prominent dentillated cornice. Unlike the marble-clad, European-inspired palaces of his contemporaries, Carnegie’s home was built to resemble a dignified English country house.

- Innovation: Despite its traditional appearance, the mansion was a marvel of modern engineering. It was one of the first private residences in the United States to have a structural steel frame, and it also featured a central heating system, a precursor to air conditioning, and a residential Otis elevator. Carnegie’s commitment to functionality and comfort was just as important as the home’s aesthetics.

- Landscape: The mansion was designed to be a freestanding house, surrounded by a large garden, which was a rare luxury in Manhattan. The garden was designed by Richard Schermerhorn, Jr., providing a spacious, green retreat for the family.

Skibo Castle, Scotland

In 1898, Carnegie purchased Skibo Castle, an ancient estate in the Scottish Highlands. He spent several years and a significant fortune transforming it into a luxurious summer retreat. The castle’s architecture is a magnificent example of the Scottish Baronial Revival style.

- Style: While the castle’s origins date back to the 12th century, Carnegie’s extensive renovations by architect Alexander Ross gave it its modern character. The Scottish Baronial style is characterized by its use of local sandstone, a rugged and asymmetrical appearance, prominent turrets, and intricate stonework.

- Renovation: Carnegie’s vision was to create a modern, comfortable home while preserving the castle’s historic essence. He added a stunning indoor swimming pavilion and a private power station to provide electricity. The interiors were designed in a grand Edwardian style, featuring beautiful wood paneling and large, ornate spaces.

- Grounds: The estate’s landscape was also a significant project. Thomas Mawson, a leading landscape architect of the day, redesigned the grounds with a focus on symmetry and the Arts and Crafts movement, including a walled garden and grand terraces, which remain a key feature of the estate today.

Carnegie’s mansions demonstrate a preference for functional and tasteful design over ostentatious display, reflecting his own rags-to-riches story and his belief in the power of industry and innovation.

Andrew Carnegie’s Family Mansions: Art

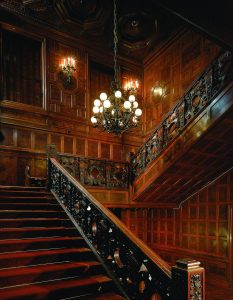

Carnegie’s New York City mansion. The grand staircase.

(Wiki Image By Unknown artist – Catalog Photo, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=64314204)

Andrew Carnegie’s approach to art in his family mansions reflected his taste for traditional, academic art and his profound conviction that art should serve a moral and educational purpose.

A Collection of Tradition and Morality 🖼️

Unlike many of his Gilded Age peers who collected European Old Masters, Carnegie’s passion was for contemporary art of his time, particularly works that told a story or conveyed a clear moral message. He favored landscapes and genre paintings (scenes from everyday life) from the French Barbizon School and the Hague School, as well as works by American and Scottish artists.

His collection was not meant to be a display of cutting-edge taste but a source of personal enjoyment and moral uplift. The art in his New York mansion and at Skibo Castle in Scotland created a comfortable, cultured, and relatively conservative environment.

The Heart of the Collection: The Art Gallery

The centerpiece of Carnegie’s New York City mansion was a large, sky-lit art gallery on the third floor. This private gallery housed the bulk of his painting and sculpture collection. A prominent feature of the gallery was a massive pipe organ, highlighting the connection Carnegie saw between the visual arts and music. This space was reserved for the family’s private enjoyment and for entertaining their personal guests.

Public Benefaction vs. Private Collection

It is crucial to note that Carnegie’s primary passion was not in building a private collection but in founding public institutions. He famously declared, “The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.” True to his “Gospel of Wealth,” he dedicated the vast majority of his fortune and energy to creating public institutions, including the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh (now the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh), which he endowed with a significant collection of art and natural history.

His private collection, while substantial, was ultimately secondary to his public mission. For Carnegie, the ultimate home for great art was in a museum, freely accessible to all people.

Andrew Carnegie’s Family Mansions: Family

Andrew Carnegie’s family life, which was primarily centered in his New York mansion and at Skibo Castle in Scotland, was small, private, and essential to him, providing a stark contrast to his immense public profile.

A Late Marriage and a Cherished Family 👨👩👧

For much of his life as a titan of industry, Andrew Carnegie was a bachelor, devoted to his business and to caring for his mother, Margaret. He married relatively late in life, at the age of 51, after his mother’s passing.

His family consisted of:

- Louise Whitfield Carnegie (1857-1946): Louise was the steady, intelligent, and private anchor of the Carnegie family. Twenty-two years younger than her husband, she shared his belief in a modest personal lifestyle despite their enormous wealth. She was a capable manager of their grand households and a key partner in his philanthropic decisions. While Andrew was the public face of their charitable giving, Louise was deeply involved behind the scenes, and she continued to manage the Carnegie Corporation’s work for decades after his death.

- Margaret Carnegie Miller (1897-1990): The only child of Andrew and Louise, Margaret was born when Carnegie was 61 years old. She was the cherished center of her parents’ world. Her upbringing was a unique mix of extraordinary privilege and her father’s “Gospel of Wealth” philosophy, which emphasized the responsibilities that came with great fortune. She grew up between the mansion on Fifth Avenue and the sprawling Skibo Castle.

Life in the Mansions

The family dynamic in the Carnegie homes was one of quiet domesticity rather than the lavish Gilded Age entertaining seen in the Vanderbilt or Astor mansions. Andrew Carnegie, particularly in his later years, was a devoted husband and a doting father.

- Skibo Castle in Scotland was the family’s beloved summer retreat, a place Carnegie referred to as “heaven on earth.” It was here that he could most fully embrace his role as a family man, away from the pressures of New York. The daily rituals at Skibo, such as being woken by a personal bagpiper, were family traditions that Margaret fondly remembered throughout her life.

After Andrew died in 1919, Louise and Margaret continued to live in the New York mansion until Louise’s passing in 1946. Margaret married Roswell Miller Jr. and had four children, ensuring the continuation of the family line, but was always guided by the principles of public service and philanthropy instilled in her by her parents.

Andrew Carnegie’s Family Mansions: Food

The food culture in Andrew Carnegie’s family mansions reflected his Scottish heritage and personal preference for simple, wholesome food over elaborate gourmet cuisine.

Simple and Hearty Fare 🍲

Despite his immense wealth, Andrew Carnegie was not a gourmand. He retained a lifelong preference for the simple, plain cooking he grew up with. His favorite dish was oatmeal, and he often began his day with a bowl of porridge. He was also fond of traditional Scottish dishes.

The family’s daily meals were substantial and well-prepared but lacked the ostentatious, multi-course French menus that were fashionable among many of his Gilded Age peers. The focus was on high-quality ingredients and straightforward preparation.

Skibo Castle: Estate-Sourced and Traditional

At Skibo Castle, their expansive summer estate in Scotland, the family enjoyed a true estate-to-table experience. The castle had its farms, gardens, and greenhouses, which supplied the kitchens with fresh vegetables, fruits, dairy, and meat.

A notable feature of life at Skibo was the traditional Scottish breakfast, which was a grand affair for guests. It typically included a wide variety of dishes, from porridge and eggs to fish and meat. While Carnegie himself ate simply, he was a hospitable host and ensured his guests were well-fed with hearty, traditional fare.

Entertaining: Hospitality Over Haute Cuisine

When the Carnegies entertained, whether in New York or at Skibo, the focus was on warm hospitality rather than elaborate gastronomy. Dinners were elegant and well-served by a professional staff, but the food itself remained relatively unpretentious. Carnegie believed that good conversation and company were more important than a fancy menu. This approach was in line with his “Gospel of Wealth” philosophy, which eschewed excessive personal luxury and extravagance.

Andrew Carnegie’s Family Mansions: Garages

Andrew Carnegie’s mansions were initially built with stables and carriage houses, which were later adapted to serve as garages as he adopted the automobile.

The Original Design: Stables and Carriage Houses 🐴

When Andrew Carnegie’s New York mansion was designed in the late 1890s and completed in 1902, the horse and carriage were still the primary mode of urban transportation. The mansion’s plans included an integrated stable and carriage house with its entrance on 90th Street, designed to house the family’s horses and various carriages.

Similarly, his grand estate at Skibo Castle in Scotland, a historic property, was equipped with extensive stables. For a vast country estate in that era, horses were essential for transportation around the grounds, for hunting, and for other recreational activities. These buildings were a standard and necessary part of the estate’s infrastructure.

Adopting the Automobile 🚗

While not a famous automotive enthusiast like some of his peers, Andrew Carnegie was a man of progress and did embrace the new technology. He owned several cars, including a custom-built Panhard-Levassor and later, Cadillacs. He reportedly preferred his chauffeur to drive at a very modest pace.

As the “horseless carriage” became a part of his life, the existing carriage houses at his mansions were the natural place to store them. These spaces were easily converted into garages, marking a clear technological transition. The story of the garage at the Carnegie mansions reflects the dawn of the automotive age, where the architecture of the horse-drawn era was adapted to accommodate a revolutionary new form of transport.

Andrew Carnegie’s Family Mansions: Grounds

(Wiki Image By valenta, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=66500535)

Andrew Carnegie’s mansions were known for their grand and thoughtfully designed grounds, which he considered just as necessary as the houses themselves. He sought out spacious plots of land to create private oases that offered a retreat from the industrial world.

New York City Mansion Grounds

In New York City, Carnegie chose a location far uptown specifically so he could have a large garden, a rarity in Manhattan. Designed by Richard Schermerhorn, Jr., the grounds were an integral part of his home.

- Layout: The 1.2-acre grounds occupied half a city block, with the Georgian Revival mansion situated on the northern side to provide ample space for a garden to the south and west. This design offered a private, sun-filled retreat for his family.