Julius Caesar, Charlemagne, and Napoleon: A Supreme Legacy on Leadership

Julius Caesar, Charlemagne, and Napoleon Bonaparte, though separated by vast stretches of time and operating in distinct historical and political landscapes, each left an indelible and supreme legacy on the art of leadership. Their rise to power, their methods of governance, and their ultimate impact demonstrate enduring principles of commanding loyalty, shaping societies, and achieving ambitious goals.

Here’s how each figure exemplified supreme leadership:

Julius Caesar (100–44 BC): The Charismatic Populist and Military Innovator

Caesar’s leadership was a blend of military genius, shrewd political instinct, and an almost magnetic personal charisma that allowed him to bypass traditional Roman power structures.

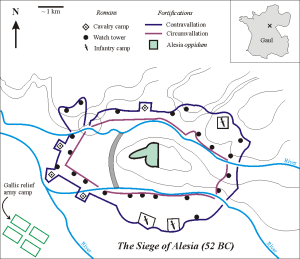

- Unparalleled Military Command: Caesar’s strategic and tactical brilliance was evident in the Gallic Wars, where he conquered vast territories against diverse and often numerous foes, and in the subsequent Civil War, where he consistently outmaneuvered and defeated more established generals like Pompey. He perfected the art of rapid maneuver, adapting his tactics to terrain and enemy, and his engineering feats (like the Rhine bridge or the siege works at Alesia) were legendary.

- Inspiring Loyalty: He cultivated fierce personal loyalty from his legions by sharing their hardships, knowing their names, and ensuring they were well-rewarded. This bond transcended the traditional loyalty to the Roman Republic, making his army a formidable personal instrument of power.

- Populist Appeal: Caesar understood the power of the common people. He leveraged populist policies—such as debt relief, land distribution, and lavish public games—to gain immense support from the urban and rural poor, effectively bypassing the senatorial elite and creating a popular mandate for his leadership.

- Decisiveness and Vision: His “crossing the Rubicon” epitomized his willingness to take decisive, irreversible action to achieve his vision of a stabilized (albeit autocratically ruled) Rome, even if it meant tearing down old traditions. He saw himself as the necessary strongman to end the Republic’s chronic instability.

Charlemagne (c. 742–814 AD): The Unifier and Cultural Architect

Charlemagne’s leadership was characterized by relentless ambition to restore order, unify diverse peoples under a Christian empire, and revive learning. He was a quintessential “Warrior King” who also deeply valued administration and culture.

- Forging an Empire from Fragmentation: Inheriting a fractured Frankish kingdom, Charlemagne spent decades campaigning, demonstrating exceptional endurance and strategic patience. His numerous military victories against Saxons, Lombards, Avars, and Moors established the largest empire in Western Europe since the fall of Rome.

- Vision for Christian Empire: Beyond conquest, Charlemagne had a clear vision of a unified Christian realm, seeing himself as the protector of the Church and the spiritual leader of his people. His coronation as “Emperor of the Romans” in 800 AD symbolized this ambition to revive the grandeur and order of the Roman Empire.

- Administrative Acumen: He recognized that military success required stable governance. He established a system of counts and missi dominici to oversee local administration, enforce his laws (capitularies), and ensure direct royal authority across his vast domains. This centralized structure was remarkable for the early medieval period.

- Patron of Learning and Culture: Charlemagne’s leadership was marked by a profound commitment to intellectual revival. He imported scholars like Alcuin, established palace and monastic schools, standardized texts, and promoted literacy. This Carolingian Renaissance was a direct result of his leadership, aimed at improving governance, promoting religious understanding, and preserving classical knowledge.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821): The Revolutionary Military Genius and Master Organizer

Napoleon’s leadership represented a new era, combining the revolutionary zeal for meritocracy with an unprecedented scale of military and administrative efficiency.

- Revolutionary Military Doctrine: Napoleon was a tactical and strategic innovator. He perfected the corps system, allowing his Grande Armée to achieve unprecedented speed, flexibility, and concentration of force on the battlefield. His use of massed artillery and combined arms was devastatingly effective.

- Inspiration and Meritocracy: He possessed an almost mythical ability to inspire his troops, who adored him and fought with fierce loyalty. He abolished aristocratic privilege in the military, promoting officers based purely on talent and courage, creating a highly motivated and capable officer corps (his famous Marshals).

- Order and Centralization: Emerging from the chaos of the French Revolution, Napoleon’s leadership provided stability and a highly centralized, efficient state. He overhauled the French administration, finances (establishing the Bank of France), and infrastructure.

- Legal Codification (Napoleonic Code): Recognizing the power of universal, clear law, his most enduring non-military legacy is the Napoleonic Code. This systematized and uniform legal code has influenced civil law systems worldwide, demonstrating its commitment to rational governance and a structured society.

- Unrivaled Ambition: His geopolitical vision was immense—to establish French hegemony over Europe and challenge global powers like Britain. This grand ambition, though ultimately leading to his downfall, pushed the boundaries of what a single leader could achieve in controlling an entire continent.

In essence, these three figures demonstrated that supreme leadership requires not only military prowess but also a compelling vision, the ability to inspire loyalty, a knack for effective administration, and a willingness to profoundly reshape the legal and social structures of their time. They are enduring examples of how individuals can leave a monumental imprint on the course of history.

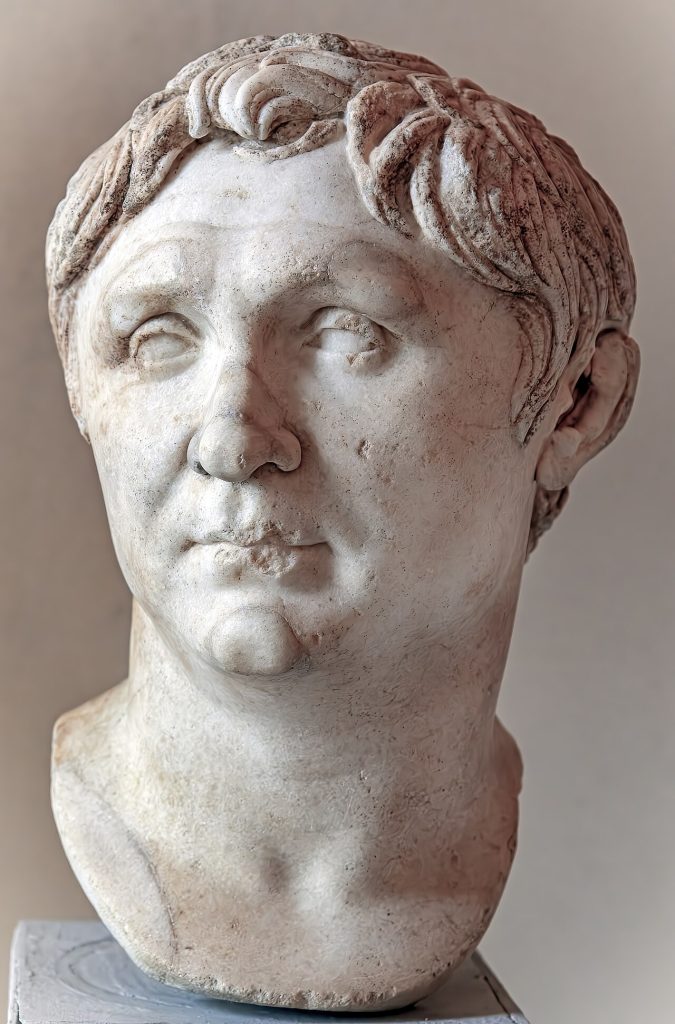

Julius Caesar (100–44 BC)

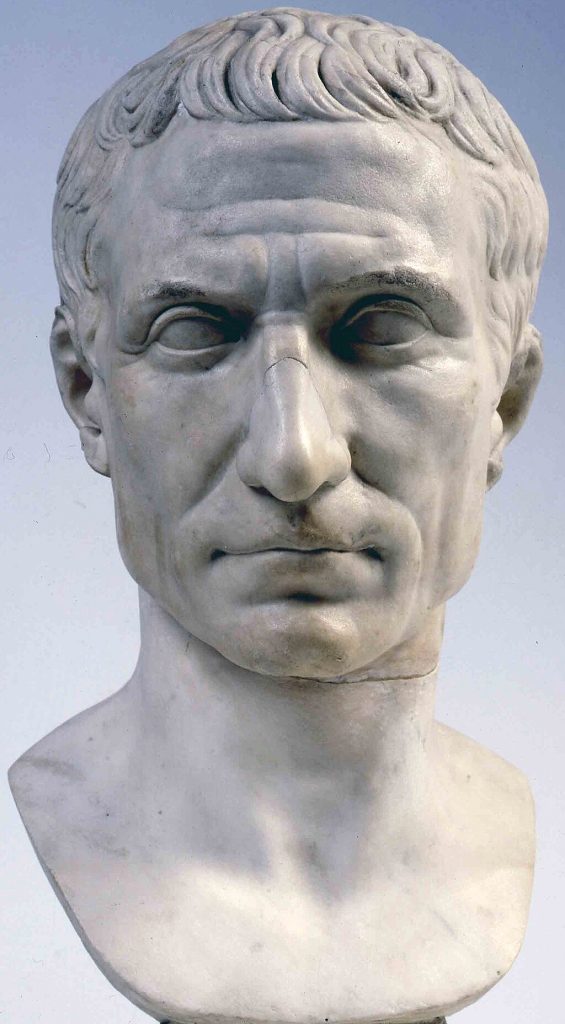

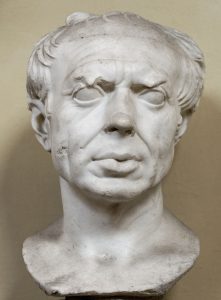

The Chiaramonti Caesar bust, a posthumous portrait in marble, 44–30 BC, Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican Museums

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – Musei Vaticani (Stato Città del Vaticano), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=49885704)

Julius Caesar 15 Quotes

Here are 15 notable quotes attributed to Julius Caesar, reflecting his personality, military genius, and political philosophy:

- “Alea iacta est.” (The die is cast.)

- Context: Uttered upon crossing the Rubicon River in 49 BC, signifying an irreversible commitment to civil war.

- “Veni, vidi, vici.” (I came, I saw, I conquered.)

- Context: His concise report to the Senate after a swift victory at the Battle of Zela in 47 BC.

- “Et tu, Brute?” (You too, Brutus?)

- Context: Alleged dying words to Marcus Junius Brutus, one of his assassins, conveying shock and betrayal.

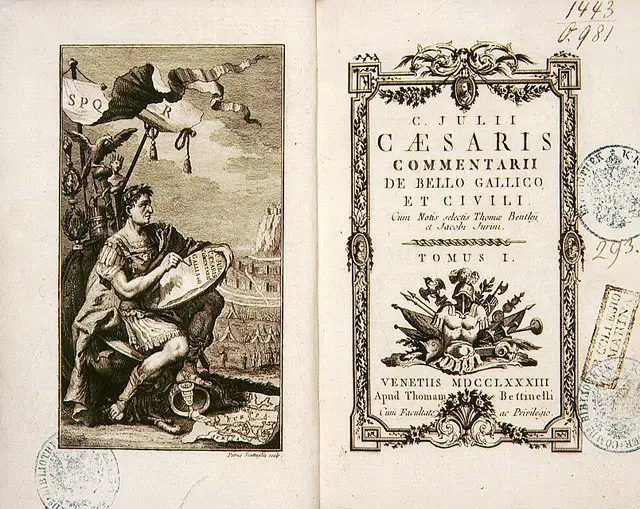

- “Omnia Gallia in tres partes divisa est.” (All Gaul is divided into three parts.)

- Context: The famous opening line of his Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries on the Gallic War).

- “Fere libenter homines id quod volunt credunt.” (Men readily believe what they wish.)

- Context: From Commentarii de Bello Gallico, a cynical observation on human nature.

- “Iacta alea est!” (The lot has been cast!)

- Context: A variant of “Alea iacta est,” sometimes cited, carries the same meaning of a fateful decision.

- “Experience is the teacher of all things.”

- Context: A more general philosophical observation attributed to him, reflecting his practical approach to learning and warfare.

- “I love the name of honor more than I fear death.”

- Context: Reflects his driving ambition and willingness to face danger for glory.

- “The enemy is within the gates; it is with our own luxury, our own folly, our own criminality that we have to contend.”

- Context: A reflection on internal Roman corruption and moral decay, indicating his concern for the Republic’s internal weaknesses.

- “It is easier to find men who will volunteer to die than to find those who are willing to endure pain with patience.”

- Context: A keen observation on courage and endurance, likely drawn from his extensive military experience.

- “In extreme danger, fear can often prove to be the most formidable of opponents.”

- Context: Highlights his understanding of psychology in warfare and leadership.

- “Cowards die many times before their deaths; the valiant never taste of death but once.”

- Context: While famously attributed to Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar, the sentiment aligns well with Roman Stoicism and Caesar’s own courageous nature.

- “No one is so brave that he is not disturbed by something unexpected.”

- Context: Acknowledges the universal human reaction to surprise, even among the most courageous.

- “If you must break the law, do it to seize power: in all other cases, observe it.”

- Context: This cynical and pragmatic quote (though its direct attribution to Caesar is debated, it reflects his actions) speaks volumes about his utilitarian approach to power and law.

- “Of all the discoveries and inventions, none could have been more important than the alphabet.”

- Context: Underscores his appreciation for literacy and knowledge, important aspects of the Carolingian Renaissance, and his own literary pursuits.

Julius Caesar YouTube Video

- Julius Caesar’s Rise To The Republic | Tony Robinson’s Romans | Timeline

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3duE5TzSWco

- Views: 2,317,430

- Julius Caesar: A Roman Colossus | Biographics

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AguS_eVoVR4

- Views: 1,261,403

- The Life of Julius Caesar – The Rise and Fall of a Roman Colossus – See U in History

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xuHwfm2lHrk

- Views: 2,421,027

- The great conspiracy against Julius Caesar – Kathryn Tempest | TED-Ed

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wgPymD-NBQU

- Views: 9,385,265

- The Story Of Julius Caesar’s Murder | Tony Robinson’s Romans: Julius Caesar Pt 2 | Timeline

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SOgDbXBDRNo

- Views: 1,444,544

Julius Caesar YouTube Video Movie

- Julius Caesar Official Trailer #1 – James Mason Movie (1953) HD by Rotten Tomatoes Classic Trailers

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uYRsMfuIAgo

- Views: 79,595

- Julius Caesar (1970) | HD Trailer by Imprint Films

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=szCavHK_7Hc

- Views: 5,417

- JULIUS CAESAR | Official Trailer | OSF 2025 by Oregon Shakespeare Festival

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DB53tlF8-Zk

- Views: 4,229

- Caesar – Movie Trailer 2025 by The SPQR Historian

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i_lQIZ_85tc

- Views: 11,973

- Senate of Rome – Christopher Walken, Richard Harris in Julius Caesar by Film&Clips by Film&Clips

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JkXaj_XzeV0

- Views: 373,684

- Julius Caesar Rallies His Men To Fight | Rome | HBO by HBO

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R2AS6JX2UDQ

- Views: 844,516

- Julius Caesar (1953) – Mark Antony’s Forum speech (starring Marlon Brando) by Through Tarantino’s Eyes

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=101sKhH-lMQ

- Views: 922,652

- Julius Caesar | HBO Rome Tribute 4K by GameLore

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jyE59WhcGRU

- Views: 374,450

Julius Caesar YouTube Video TV

- Julius Caesar Rallies His Men To Fight | Rome | HBO by HBO

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R2AS6JX2UDQ

- Views: 844,516

- Julius Caesar Weighs A Truce With Pompey | Rome | HBO by HBO

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8dHgi1Y-Nhg

- Views: 300,839

- Julius Caesar and Mark Antony discuss Lucius Vorenus (ROME HBO) [HD Scene] by Octavian, Caesar Augustus

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ap2Bs3zESYM

- Views: 39,310

- Brutus & Cicero Surrender To Julius Caesar | Rome | HBO by HBO

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HufZQN5m4Vw

- Views: 392,653

Documentaries

- Julius Caesar’s Rise To The Republic | Tony Robinson’s Romans | Timeline by Timeline – World History Documentaries

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3duE5TzSWco

- Views: 2,330,505

- The Life of Julius Caesar – The Rise and Fall of a Roman Colossus – See U in History by See U in History / Mythology

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xuHwfm2lHrk

- Views: 2,429,290

- Caesar in Gaul – Roman History DOCUMENTARY by Kings and Generals

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LRV185XaMIM

- Views: 9,904,316

- Ancient Empires: Caesar Rebuilds the Roman Republic | Exclusive by HISTORY

- URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_zy1Ee3rjdk

- Views: 75,660

Julius Caesar Books

For a single, definitive modern biography of Julius Caesar, the best choice is “Caesar: Life of a Colossus” by Adrian Goldsworthy.

The life of Julius Caesar is one of the most documented in the ancient world, and the number of books about him is immense. Here are some of the most essential and highly-regarded options.

The Definitive Modern Biography 👑

“Caesar: Life of a Colossus” by Adrian Goldsworthy

This is the standard for modern biographies of Caesar. Goldsworthy is a renowned Roman historian who presents a comprehensive and highly readable narrative of Caesar’s life, from his youth to his assassination. The book expertly weaves together the political, military, and personal aspects of his story, providing excellent context for the turbulent world of the late Roman Republic.

The Essential Primary Sources 📜

“The Gallic War” and “The Civil War” by Julius Caesar

Written by Caesar himself, these are the most important primary sources for his career. The Gallic War is a gripping, firsthand account of his nine-year campaign to conquer Gaul (modern France). The Civil War is his justification for the war against his rival, Pompey the Great. While they are masterfully written pieces of political propaganda, they offer unparalleled insight into Roman warfare and the mind of a military genius.

For a Focus on His Rise to Power

“Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic” by Tom Holland

While not a biography of Caesar alone, this book is a brilliantly written and fast-paced narrative of the final decades of the Roman Republic. It tells the story of the generation of ambitious and violent men—including Pompey, Crassus, Cicero, and Cato—who tore the Republic apart. Caesar is a central figure, and the book does a fantastic job of explaining the political chaos that made his rise to absolute power possible.

On His Assassination

“The Death of Caesar: The Story of History’s Most Famous Assassination” by Barry Strauss

For readers fascinated by the dramatic end of Caesar’s life, this book is a must-read. Strauss provides a thrilling, minute-by-minute account of the Ides of March, 44 BCE. He delves into the motives of the assassins, like Brutus and Cassius, and explores the political aftermath of the murder that plunged Rome back into civil war.

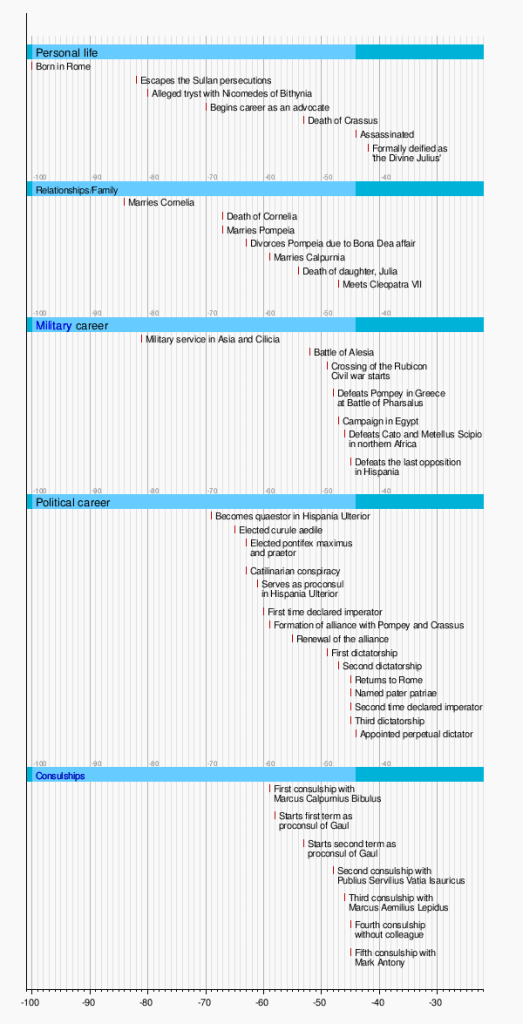

Chronology

The extent of the Roman Republic in 40 BC after Caesar’s conquests

(Wiki Image By Tataryn77 – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11154814)

Julius Caesar History

Vercingetorix throws down his arms at the feet of Julius Caesar, as depicted in a painting by Lionel Royer in 1899. Musée Crozatier, Le Puy-en-Velay, France.

(Wiki Image By Lionel Royer – Musée CROZATIER du Puy-en-Velay. — http://www.mairie-le-puy-en-velay.fr.http://forum.artinvestment.ru/blog.php?b=273473&langid=5, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1218850)

Gaius Julius Caesar (100–44 BC) was a Roman general, statesman, and dictator who played a critical role in the events that led to the demise of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. His life was a dramatic saga of ambition, military genius, political maneuvering, and ultimately, a violent end that reshaped the course of Western history.

Here’s a historical overview of his life:

Early Life and Political Ascent (100-61 BC):

- Birth and Patrician Family: Born in Rome, Caesar belonged to the gens Julia, a patrician (aristocratic) family that claimed descent from Iulus, the son of the Trojan prince Aeneas, and through him, from the goddess Venus. While noble, his family was not particularly wealthy or politically dominant in his youth.

- Early Career and Sulla’s Proscriptions: His early life was marked by political turmoil in Rome. He famously defied the dictator Sulla, who ordered him to divorce his wife Cornelia (daughter of a political rival of Sulla). Caesar refused and had to go into hiding, briefly serving in the military in Asia Minor to avoid Sulla’s proscriptions.

- Rise Through the Cursus Honorum: After Sulla’s death, Caesar began his steady ascent through the cursus honorum (the traditional sequence of public offices). He held positions such as military tribune, quaestor (financial administrator), aedile (responsible for public games and buildings, which he used to gain popularity through lavish spectacles funded by loans), and praetor (a judicial official and military commander).

- Pontifex Maximus (63 BC): He was elected Pontifex Maximus, the chief high priest of Rome, a position that held significant political power due to its religious authority.

- Governorship in Spain (61-60 BC): He served as governor of the Roman province of Hispania Ulterior, where he gained significant military success and wealth, earning him a triumph (a parade celebrating military victory).

The First Triumvirate and the Gallic Wars (60-50 BC):

- Formation of the Triumvirate (60 BC): Recognizing the gridlock of Roman politics and the power of the military, Caesar formed an unofficial political alliance, known as the First Triumvirate, with two of Rome’s most powerful men: Gnaeus Pompey Magnus (Pompey the Great), a celebrated general, and Marcus Licinius Crassus, Rome’s wealthiest man. This alliance enabled them to bypass the Senate and exert significant influence over Roman politics through their combined power. Caesar solidified this alliance by marrying his daughter Julia to Pompey.

- Consulship (59 BC): With the Triumvirate’s support, Caesar was elected consul, the highest office in the Republic. He used his consulship to push through populist legislation, including land reform for Pompey’s veterans, often resorting to intimidation and force, further alienating the conservative Senate.

- Conquest of Gaul (58-50 BC): After his consulship, Caesar secured the governorship of Gaul (modern-day France and Belgium) for an extended period. Over the course of eight years, his legions systematically conquered the diverse Gallic tribes. His campaigns, meticulously chronicled in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries on the Gallic War), showcased his military genius, logistical skills (e.g., building a bridge over the Rhine in 10 days), and brutal efficiency (e.g., the siege of Alesia where he defeated a massive Gallic force under Vercingetorix while simultaneously fending off a Roman relief army). These conquests brought him immense wealth, military glory, and the unwavering loyalty of his legions. He also conducted exploratory expeditions to Britain.

Civil War and Dictatorship (49-43 BC):

- Dissolution of the Triumvirate: The alliance began to unravel with the death of Crassus in 53 BC and, crucially, the death of Caesar’s daughter Julia in 54 BC, which removed the personal bond between Caesar and Pompey. Pompey increasingly aligned himself with the Senate, which grew fearful of Caesar’s immense power and popularity.

- Crossing the Rubicon (49 BC): The Senate, led by Pompey, ordered Caesar to disband his army and return to Rome as a private citizen to face potential prosecution. In a momentous act of defiance, Caesar famously led his legion across the Rubicon River, the boundary between his province and Italy, effectively declaring civil war. This gave rise to the idiom “crossing the Rubicon,” meaning to pass a point of no return.

- Victories in Civil War: The ensuing Civil War (49-45 BC) saw Caesar confront Pompey and the senatorial forces across the Roman world. He quickly secured Italy, then defeated Pompey’s forces in Spain. He then pursued Pompey to Greece, achieving a decisive victory at the Battle of Pharsalus (48 BC). Pompey fled to Egypt, where agents of Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII assassinated him. Caesar subsequently intervened in an Egyptian dynastic dispute, famously beginning his affair with Cleopatra VII. He went on to defeat the remaining Pompeian forces in Africa (Battle of Thapsus, 46 BC) and Spain (Battle of Munda, 45 BC), securing his sole control of Rome.

- Dictatorship for Life: After his victories, Caesar accumulated unprecedented power. He was repeatedly appointed dictator, eventually being declared Dictator Perpetuo (dictator for life) in 44 BC. He centralized power, reduced the Senate’s authority, and launched numerous reforms:

- Julian Calendar: One of his most lasting legacies is a solar-based calendar that significantly improved accuracy and is the direct predecessor of the Gregorian calendar we use today.

- Land Reform and Veteran Settlement: Continued his policy of distributing land to veterans and the poor.

- Debt Relief: Implemented measures to alleviate debt.

- Public Works: Began ambitious building projects in Rome to provide employment and glorify his rule (e.g., the Forum of Caesar).

- Citizenship Expansion: Extended Roman citizenship to various communities outside Italy.

Assassination and Legacy (44 BC):

- Fears of Monarchy: Despite his widespread reforms, Caesar’s accumulation of absolute power and disregard for Republican traditions caused growing alarm among many senators, who feared he intended to establish a monarchy and destroy the Republic.

- Ides of March (March 15, 44 BC): A group of senators, including his trusted friends Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus, conspired against him. On the Ides of March, Caesar was assassinated, stabbed multiple times on the floor of the Senate House.

- Aftermath and Legacy: The conspirators hoped to restore the Republic, but Caesar’s assassination plunged Rome into another round of civil wars. Ultimately, his adopted heir, Octavian (later Augustus), emerged victorious, consolidating power and establishing the Roman Empire. Caesar’s life and death became a powerful symbol of ambition, fate, and political upheaval, profoundly influencing later leaders and thinkers; his name also became a title for rulers (e.g., Kaiser, Tsar).

Julius Caesar: Early Life and Political Ascent (100-61 BC)

Gaius Marius, Caesar’s uncle and the husband of Caesar’s aunt Julia. He was an enemy of Sulla and took Rome with Lucius Cornelius Cinna in 87 BC.

Gaius Marius, Caesar’s uncle and the husband of Caesar’s aunt Julia. He was an enemy of Sulla and took Rome with Lucius Cornelius Cinna in 87 BC.

(Wiki Image By Marie-Lan Nguyen (2009), CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8962374)

I can detail Julius Caesar’s early life and political ascent up to 61 BC. This period was crucial for establishing the foundation of his power and influence.

Gaius Julius Caesar was born in Rome in 100 BC into the gens Julia, one of Rome’s most ancient and distinguished patrician families. While boasting a legendary lineage tracing back to Iulus (son of the Trojan prince Aeneas) and ultimately the goddess Venus, his branch of the family was not among the wealthiest or most politically dominant during his youth.

Early Challenges and Political Affiliations:

- Political Turmoil: Caesar’s early life unfolded during a period of intense civil strife in the Roman Republic, marked by the violent rivalry between two powerful factions: the Populares (champions of the people, seeking reforms) and the Optimates (conservatives, favoring the senatorial aristocracy).

- Marius’s Influence: His aunt, Julia, was the wife of Gaius Marius, a renowned Populares general who challenged Sulla. This familial connection linked Caesar early to the popular faction.

- Sulla’s Proscriptions: When the Optimate general Sulla emerged victorious as dictator, he initiated brutal proscriptions against his political enemies. Caesar, then a young man, was ordered to divorce his wife Cornelia, whose father, Lucius Cornelius Cinna, was a prominent Marian supporter. Caesar famously refused, risking his life, and had to go into hiding. It’s said that Sulla, recognizing Caesar’s dangerous ambition, remarked, “Beware the boy with the loose tunic,” or “in Caesar there are many Mariuses.” To escape the immediate danger, Caesar left Rome and served in the military in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey).

Ascension Through the Cursus Honorum: Upon Sulla’s eventual retirement and death, Caesar cautiously returned to Rome and began his methodical climb through the cursus honorum, the traditional sequence of public offices for Roman aristocrats:

- Military Tribune: He served in various military capacities in the East, gaining practical experience.

- Quaestor (69 BC): This was his first significant public office, involving financial administration. As quaestor, he gained automatic entry into the Roman Senate. During this time, both his beloved wife Cornelia and his elderly aunt Julia (Marius’s widow) died. Caesar delivered memorable funeral eulogies for both women, shrewdly using the occasion to publicly honor the popular Marius and subtly align himself with the Populares faction, further endearing himself to the common people. He also served as quaestor in Hispania Ulterior.

- Aedile (65 BC): As aedile, Caesar was responsible for public games, buildings, and the grain supply. He seized this opportunity to gain immense popularity by putting on lavish and spectacular public games and gladiatorial contests, often financing them heavily through loans, accumulating substantial debt in the process. He understood the power of public display to cultivate popular support.

- Pontifex Maximus (63 BC): In a bold and surprising move for a relatively young man, Caesar won the election for Pontifex Maximus, the chief high priest of Rome. This was an extremely prestigious and politically powerful religious office, granting him influence over the Roman state religion and law. He achieved this victory over older, more established candidates through popular support and perhaps clever political maneuvering.

- Praetor (62 BC): He served as a praetor, a senior judicial official who also held military command. This office further enhanced his legal and military experience.

- Governorship in Hispania Ulterior (61 BC): After his praetorship, Caesar was appointed governor of Hispania Ulterior (Further Spain). This was a crucial turning point. During his governorship, he engaged in successful military campaigns against local tribes, showcasing his military acumen, expanding Roman territory, and acquiring considerable personal wealth (largely through plunder). This wealth allowed him to begin paying down his immense debts and, more importantly, provided him with veteran legions loyal to him, not the Senate. His military victories in Spain also earned him the right to a triumph (a glorious parade celebrating military victory) upon his return to Rome.

By the end of 61 BC, Julius Caesar had, through strategic alliances (though the First Triumvirate was still being formalized), popular appeals, and military success, positioned himself as a rising star in Roman politics, ready to contend for the ultimate prize: the Consulship.

Julius Caesar: The First Triumvirate and the Gallic Wars (60-50 BC)

A reconstructed section of the Alesia investment fortifications

A reconstructed section of the Alesia investment fortifications

(Wiki Image CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=626376)

Julius Caesar’s career from 60 to 50 BC was a pivotal decade that saw him forge a powerful political alliance, gain immense military glory, and accumulate the wealth and loyal legions that would enable his later rise to absolute power. This period is defined by the First Triumvirate and the Gallic Wars.

The First Triumvirate (c. 60 BC)

By 61 BC, Caesar had returned from his successful governorship in Spain, seeking the consulship (the highest political office in Rome). However, he faced significant opposition from the conservative senatorial elite (the Optimates), who feared his growing popularity and ambition. To overcome this political deadlock, Caesar formed an unofficial but highly effective political alliance known as the First Triumvirate.

- Key Members:

- Gaius Julius Caesar: A rising political star with burgeoning popularity among the people and a solid military record.

- Gnaeus Pompey Magnus (Pompey the Great): Rome’s most celebrated general, who felt slighted by the Senate’s refusal to ratify his eastern settlements and grant land to his veterans.

- Marcus Licinius Crassus: Rome’s wealthiest man, a powerful financier and politician who sought to expand his influence and protect his business interests.

- Purpose: This alliance, formed around 60 BC, was a pragmatic agreement where the three men pledged to use their combined influence to support each other’s political aims, bypassing the traditional power of the Senate.

- Consolidation of Power: Caesar solidified the alliance by marrying his only daughter, Julia, to Pompey. With the Triumvirate’s support, Caesar was elected Consul for 59 BC. During his consulship, he pushed through key legislation, including land reform for Pompey’s veterans, often using intimidation and popular support to overcome senatorial opposition.

The Gallic Wars (58–50 BC)

Following his consulship, Caesar secured the governorship of Cisalpine Gaul, Transalpine Gaul, and Illyricum for an extended period, which granted him immunity from prosecution and, crucially, command of four legions. This set the stage for his legendary conquest of Gaul.

- Initial Campaigns (58-57 BC): Caesar quickly intervened in Gaul, initially to prevent the Helvetti from migrating through Roman territory and then to repel Germanic incursions led by Ariovistus. These early victories established Roman dominance and gave him a pretext for further involvement.

- Systematic Conquest (57-53 BC): Over the next several years, Caesar systematically conquered the various Gallic tribes (Belgae, Nervii, Aquitani, etc.), extending Roman control across vast territories roughly corresponding to modern-day France, Belgium, and parts of Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands. His campaigns were marked by:

- Rapid Maneuver: Caesar’s legions were known for their incredible marching speed, often catching Gallic tribes by surprise.

- Brutal Efficiency: He was ruthless in suppressing resistance, leading to massive casualties among the Gallic population.

- Engineering Feats: His legions demonstrated remarkable engineering prowess, notably building a bridge over the Rhine River in just 10 days to intimidate Germanic tribes and constructing elaborate siege works.

- Invasions of Britain (55 & 54 BC): Caesar launched two exploratory expeditions to Britain, the first Roman general to do so. While not leading to permanent conquest at this time, they extended Roman influence and prestige.

- The Great Gallic Revolt and Alesia (52 BC): The most significant challenge came from a unified Gallic revolt led by Vercingetorix. Caesar famously besieged Vercingetorix’s forces at the hillfort of Alesia. In an incredible feat of military engineering, Caesar constructed a double line of fortifications: an inner circumvallation to contain Vercingetorix and an outer contravallation to defend against a massive Gallic relief army. His decisive victory here effectively crushed organized Gallic resistance.

- Consolidation and Pacification (51-50 BC): The final years involved mopping up remaining pockets of resistance and establishing Roman administration in the newly conquered territories.

Impact of the Period

By 50 BC, Caesar had transformed from an ambitious politician into Rome’s most celebrated and powerful general. The Gallic Wars provided him with:

- Immense Wealth: Enabling him to pay off his massive debts and fund further political ambitions.

- Unparalleled Military Glory: Elevating his standing among the Roman people and his soldiers.

- Veteran Legions: A battle-hardened, loyal army devoted to him personally, not the Senate.

However, his extended command, wealth, and the unwavering loyalty of his legions also fueled the deep suspicions of the conservative Senate and ultimately contributed to the breakdown of the First Triumvirate and the outbreak of the Roman Civil War. This decade laid the direct foundation for his eventual rise to dictatorship and the fall of the Roman Republic.

Julius Caesar: Civil War and Dictatorship (49-43 BC)

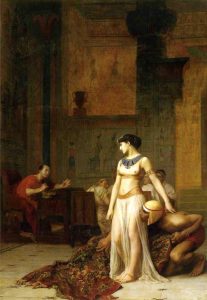

Cleopatra and Caesar, 1866 painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme

Cleopatra and Caesar, 1866 painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme

(Wiki ImageBy Jean-Léon Gérôme – http://www.mezzo-mondo.com/arts/mm/orientalist/european/gerome/index_b.html Archived 2017-06-19 at the Wayback Machine, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1399233)

Julius Caesar’s Civil War and subsequent dictatorship (49-44 BC) represent the pivotal period of his life, marking a profound transformation of the Roman Republic into what would eventually become an empire.

The Roman Civil War (49–45 BC)

The conflict erupted due to escalating tensions between Caesar, who had just completed his highly successful Gallic Wars, and the Roman Senate, particularly Pompey the Great, his former ally in the First Triumvirate. The Senate, fearing Caesar’s immense power, popularity, and the unwavering loyalty of his legions, ordered him to disband his army and return to Rome as a private citizen, which would have left him vulnerable to prosecution by his political enemies.

- Crossing the Rubicon (January 49 BC): In a decisive act of defiance, Caesar famously led one of his legions across the Rubicon River, the boundary between his province of Cisalpine Gaul and Italy proper. This act, traditionally marked by the phrase “Alea iacta est” (The die is cast), signaled his irreversible commitment to civil war against the Roman state.

- Initial Victories in Italy and Spain (49 BC): Caesar quickly marched on Rome, which Pompey and most of the senators abandoned, fleeing to the East. Caesar secured Italy with surprising speed. He then swiftly moved to Hispania (Spain) to defeat Pompey’s legions there, preventing them from reinforcing his main forces.

- Campaign in Greece and Battle of Pharsalus (48 BC): Caesar then pursued Pompey to Greece. After suffering a tactical defeat at Dyrrhachium, Caesar lured Pompey into a decisive pitched battle at Pharsalus (August 48 BC). Despite being significantly outnumbered, Caesar’s veteran legions achieved a stunning victory, completely routing Pompey’s army. Pompey fled to Egypt, where he was assassinated upon his arrival by agents of Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII, who hoped to curry favor with Caesar.

- Egyptian Interlude (48–47 BC): Caesar followed Pompey to Egypt. Upon discovering Pompey’s death, he became embroiled in the dynastic dispute between Ptolemy XIII and his sister, Cleopatra VII. Caesar sided with Cleopatra, and after a brief war (the Alexandrian War), he secured her position as queen, initiating their famous affair and ensuring Egypt’s vital grain supply for Rome.

- Battles in Africa and Spain (46–45 BC): Despite Pharsalus, resistance to Caesar continued. He had to conduct further campaigns to eliminate the remaining Pompeian and Optimate forces:

- Battle of Thapsus (46 BC): Caesar decisively defeated the combined forces of Metellus Scipio and Cato the Younger in Africa. Cato famously committed suicide rather than live under Caesar’s rule.

- Battle of Munda (45 BC): His final major battle, fought in Hispania against Pompey’s sons, Gnaeus Pompey and Sextus Pompey. This was a hard-fought victory that effectively ended organized resistance to Caesar.

Dictatorship (49–44 BC)

With his military victories complete, Caesar returned to Rome as the undisputed master of the Roman world. He quickly amassed an unprecedented concentration of power, signaling the de facto end of the Roman Republic and setting the stage for the Empire.

- Accumulation of Powers: Caesar was appointed dictator multiple times, holding the office briefly in 49 BC, then for a year in 48 BC, for ten years in 46 BC, and finally, in February 44 BC, he was declared Dictator Perpetuo (Dictator for Life). He also held numerous consulships concurrently, was made Pontifex Maximus (Chief Priest), and received many other honors, effectively centralizing all power in his hands.

- Major Reforms: During his dictatorship, Caesar embarked on an ambitious program of reforms aimed at bringing order and efficiency to Rome and its provinces:

- Julian Calendar (45 BC): His most enduring reform was the overhaul of the Roman calendar. Based on a solar year, the Julian calendar (with its leap year system) was far more accurate and became the standard for centuries, directly influencing our modern Gregorian calendar.

- Land Reform and Veteran Settlement: He continued to distribute public land to his veteran soldiers (rewarding their loyalty) and to the urban poor, aiming to alleviate social unrest and provide economic opportunities.

- Debt Relief: He implemented measures to alleviate debt burdens, which were popular among the lower classes but displeased creditors.

- Judicial and Administrative Reforms: He reformed the judicial system, regulated local governments throughout Italy, and began an ambitious program of public works in Rome (e.g., the Forum of Caesar) to provide employment and beautify the city.

- Citizenship: He extended Roman citizenship to various communities outside Italy, particularly in Gaul, integrating them more fully into the Roman state.

Julius Caesar: Assassination and Legacy (44 BC)

Ides of March coin minted by Brutus in 43–42 BC. The daggers and pileus celebrate the assassination of Julius Caesar.

(Wiki Image By British Museum – https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/C_1860-0328-124, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=136438225)

The Assassination

On the Ides of March, a group of around 60 to 80 Roman senators, led by Marcus Junius Brutus, Gaius Cassius Longinus, and Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, conspired to kill Caesar. Their motive was primarily to prevent Caesar from becoming an absolute monarch, believing his accumulation of power (including being declared “dictator for life”) threatened the Republic’s traditional institutions and liberties.

The assassination took place during a Senate meeting at the Curia of Pompey, located within the Theatre of Pompey. The conspirators, armed with daggers concealed beneath their togas, surrounded Caesar. Tillius Cimber signaled the attack by grabbing Caesar’s toga, and Publius Servilius Casca struck the first blow. Caesar reportedly cried out, “Why, this is violence!” According to some accounts, upon seeing Brutus among his attackers, Caesar uttered the famous words, “Et tu, Brute?” (You too, Brutus?). He was stabbed approximately 23 times and fell at the foot of a statue of his former rival, Pompey the Great.

Legacy of the Assassination

Far from restoring the Republic, Caesar’s death initiated a new, devastating phase of civil wars and fundamentally reshaped the course of Roman history:

- Political Vacuum and Instability: The conspirators had no clear plan for what would follow Caesar’s death. Their act created a massive power vacuum and immediately plunged Rome into renewed political turmoil and civil unrest. The populace, who largely supported Caesar due to his populist reforms and generosity (including provisions in his will for them), reacted with outrage against the assassins.

- Rise of the Second Triumvirate: Caesar’s powerful allies, particularly Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony), and his newly revealed adopted heir, Gaius Octavius (Octavian), quickly moved to avenge his death. In 43 BC, they formed the Second Triumvirate with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. This was a legally sanctioned, highly authoritarian alliance, unlike the informal First Triumvirate, explicitly formed to restore order and punish Caesar’s murderers.

- Defeat of the “Liberators”: The Triumvirs ruthlessly pursued the conspirators. Brutus and Cassius raised armies in the East but were decisively defeated by Antony and Octavian at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC. Both Brutus and Cassius committed suicide.

- End of the Roman Republic: The period after Caesar’s death was marked by intense power struggles among the Triumvirs themselves. Ultimately, Octavian defeated Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium (31 BC) and consolidated all power. He shrewdly avoided Caesar’s mistake of flaunting monarchical titles, instead adopting the title of Princeps (first citizen) and later Augustus, effectively becoming the first Roman Emperor. Caesar’s assassination, therefore, accelerated the demise of the Republic and ushered in the autocratic Roman Empire, which lasted for centuries.

- Deification of Caesar: Octavian further solidified his own legitimacy by having Caesar officially deified as Divus Iulius (the Divine Julius). This act made Octavian the “son of a god,” boosting his prestige and setting a precedent for the deification of future emperors.

- Enduring Symbolism: Caesar’s assassination became a powerful symbol of political betrayal and the conflict between individual ambition and republican ideals, famously dramatized in William Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar. His name and legacy continued to resonate throughout history, with “Caesar” becoming a title for rulers (e.g., Kaiser, Tsar).

Julius Caesar: Advisors

Bust found in the Licinian Tombs in Rome, traditionally identified as Crassus.

(Wiki Image By Sergey Sosnovskiy – https://ancientrome.ru/art/artworken/img.htm?id=2339, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=138203529)

Julius Caesar, a masterful politician and military commander, relied on a close circle of advisors and loyal lieutenants throughout his career. These individuals played crucial roles in his military campaigns, political maneuvering, and administrative efforts.

Some of his most notable advisors included:

- Marcus Licinius Crassus: Though technically a political ally in the First Triumvirate rather than a direct advisor in the military sense, Crassus’s immense wealth and influence were critical to Caesar’s early political ascent. Crassus provided significant financial backing, helping Caesar to fund his lavish public games and overcome massive debts, thus enabling his political career.

- Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great): Another member of the First Triumvirate, Pompey was a seasoned military general whose initial political alliance with Caesar was based on mutual ambition and shared opposition to the conservative Senate. While their relationship eventually devolved into civil war, in the early stages of the Triumvirate, Pompey’s military prestige and influence offered a crucial balance and shared power with Caesar.

- Mark Antony: A loyal and highly capable military commander, Mark Antony was one of Caesar’s most trusted lieutenants. He served with distinction in Gaul and played a critical role during the Civil War, often acting as Caesar’s second-in-command. Antony managed affairs in Italy during Caesar’s absences and was a strong advocate for Caesar’s interests. His unwavering loyalty and military prowess made him an indispensable advisor and enforcer of Caesar’s will.

- Titus Labienus: Initially one of Caesar’s most brilliant and trusted legates in Gaul, Labienus was a highly effective military commander, often left in charge of entire legions. He was considered Caesar’s second-in-command during much of the Gallic Wars. However, as the civil war approached, Labienus dramatically defected to Pompey’s side, becoming one of Caesar’s most formidable republican opponents. His defection highlights the personal and political complexities of allegiances in that era.

- Aulus Hirtius: Hirtius was another close associate and military officer who served under Caesar in Gaul. He was also a skilled writer and historian, known for completing Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic War with an eighth book and likely contributing to other historical accounts of the civil wars. His literary and administrative skills made him a valuable member of Caesar’s inner circle.

- Gaius Oppius: A wealthy and influential equestrian, Oppius was a key figure in managing Caesar’s financial and political affairs in Rome while Caesar was on campaign. He served as a trusted agent, handling correspondence, public relations, and private business, demonstrating the importance of behind-the-scenes administrative and financial support.

- Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus & Gaius Trebonius: Both were highly effective legates who served Caesar with distinction in Gaul and during the Civil War. Despite their past loyal service and the honors Caesar bestowed upon them, they famously became prominent conspirators in his assassination, driven by their belief in restoring the Republic.

- His Legionary Commanders: Caesar surrounded himself with competent legates and centurions who executed his daring military plans with precision.

These individuals, along with other loyal officers and administrators, formed the essential support system that enabled Julius Caesar to achieve his extraordinary military victories and implement his far-reaching political reforms, ultimately transforming the Roman Republic.

Julius Caesar: Civilization

A Roman bust of Pompey the Great made during the reign of Augustus (27 BC – 14 AD), a copy of an original bust from 70 to 60 BC, Venice National Archaeological Museum, Italy

(Wiki Image By Didier Descouens – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=142571890)

Julius Caesar: Economic

Julius Caesar’s economic policies and impact were deeply intertwined with his political ambitions and military endeavors. He addressed several pressing economic issues of his time, often with an eye towards gaining popular support and stabilizing the Roman state to facilitate his rule.

Here are the key aspects of Julius Caesar’s economic actions:

- Addressing the Debt Crisis: Rome faced significant issues with widespread debt, particularly among the urban poor and even some elites. Caesar, who himself had incurred massive debts earlier in his career to fund his political rise and lavish public games, understood this problem intimately.

- As dictator, he enacted debt reform laws in 48 BC. These included allowing interest already paid on loans to be deducted from the principal, and mandating that property be accepted for repayment at its pre-Civil War value, which was higher than current depressed market rates. He also reinforced an older law limiting the amount of cash a person could hold. These measures aimed to ease the burden on debtors and bring some stability to the financial system, though they often angered creditors.

- Land Reform and Veteran Settlement: A core component of Caesar’s populist agenda was land redistribution.

- He famously used public lands (and later, confiscated enemy lands) to settle his vast numbers of veteran soldiers, providing them with a livelihood after their service. This also served to secure their unwavering loyalty to him.

- He also distributed land to the urban poor and landless citizens, aiming to alleviate poverty and unemployment in Rome.

- Grain Dole Reform: The grain dole, a system of distributing free or subsidized grain to the Roman populace, was a significant drain on the public treasury and a potential source of corruption.

- Caesar reformed the grain dole, drastically reducing the number of recipients from approximately 320,000 to 150,000. He made the system more efficient and transparent, ensuring that only genuinely needy citizens received benefits and discouraging people from simply moving to Rome to get on the dole.

- He also improved the administration of Rome’s grain supply from the provinces, particularly from Egypt, after securing it under Cleopatra.

- Public Works and Employment: To alleviate unemployment and enhance Rome’s infrastructure, Caesar undertook a series of ambitious public works projects.

- These included the construction of the Forum of Caesar, new temples, and improvements to harbors and roads. He also laid plans for large-scale engineering projects like draining the Pontine Marshes south of Rome (for agricultural land) and building a canal through the Isthmus of Corinth (to improve trade routes). These projects provided jobs for the urban poor and stimulated the economy.

- Taxation and Revenue:

- Caesar’s military conquests, particularly in Gaul, generated immense wealth for the Roman treasury through plunder, tribute, and new taxes imposed on the conquered provinces. This influx of wealth helped to finance his vast armies and public works.

- He also introduced new taxes, such as Rome’s first sales tax, and increased duties on luxury imports. He sought to reform the often corrupt provincial tax collection system.

- Monetary Policy: Caesar introduced a new, more stable gold coin called the Aureus, which helped to standardize currency and provide a reliable medium for large transactions. This contributed to greater economic stability.

Overall Impact:

Caesar’s economic policies were designed to bring stability to the Republic after years of civil strife, reward his supporters, and fund his ambitious military and political agenda. While some measures were controversial (especially those affecting creditors or limiting the dole), many provided genuine relief and improved the lives of the lower classes. His policies, coupled with the vast wealth generated from his conquests, contributed to a period of economic expansion and laid some of the groundwork for the prosperity seen during the early Roman Empire under Augustus, although the financial costs of his numerous wars were immense.

Here are images related to the economic aspects of Julius Caesar’s era:

- Roman Coins: During Caesar’s time, coins like the denarius were the backbone of the Roman economy. Caesar himself issued coins, often featuring his own image, which was a significant political and economic statement.

- Roman Trade Routes: Trade was vital to the Roman economy, as it brought goods and wealth from across the Mediterranean and beyond. Caesar’s conquests, particularly in Gaul, expanded Roman territory and opened new trade opportunities.

- Roman Infrastructure Projects: Caesar initiated numerous infrastructure projects, including roads, public buildings, and port improvements, which stimulated the economy by creating jobs and facilitating trade and communication.

Julius Caesar: Farming

During Julius Caesar’s time (1st century BC), Roman agriculture was the backbone of the economy, but it was also undergoing significant changes and facing severe social and economic tensions. Caesar’s policies directly addressed these issues, particularly concerning land ownership and the welfare of the rural population.

Roman Agriculture in the Late Republic

- Smallholding Decline: The traditional Roman ideal of the citizen-farmer with a small plot of land was in decline. Decades of warfare had drawn many small farmers away from their lands, and upon returning, they often found their farms neglected or bought up by wealthy landowners.

- Rise of Large Estates (Latifundia): Wealthy aristocrats and equestrians consolidated vast tracts of land into large estates (latifundia). These estates specialized in cash crops like grapes (for wine) and olives (for olive oil), and increasingly relied on slave labor (a massive influx of slaves from conquests), rather than free Roman citizens.

- Grain Production: While some areas of Italy produced grain, Rome’s massive and growing population (especially the urban poor) relied heavily on grain imported from fertile provinces like Sicily, North Africa, and later, Egypt.

Caesar’s Policies Related to Farming

Caesar recognized the political instability caused by landlessness and rural poverty, and his agrarian laws were central to his populist agenda:

- Land Distribution for Veterans and the Poor: A key component of his reforms was extensive land redistribution.

- He settled large numbers of his veteran soldiers on agricultural lands throughout Italy and the provinces, particularly in new colonies. This was a crucial way to reward their loyalty and provide them with a livelihood after their service.

- He also distributed public lands (ager publicus) and occasionally confiscated enemy lands to provide for the urban poor and landless citizens. These distributions aimed to alleviate poverty, reduce urban unemployment by moving people back to the countryside, and establish a more stable citizen base.

- Emphasis on Free Labor: Caesar’s agrarian laws included provisions that mandated large landowners using public pasture lands to employ a certain proportion of free labor (citizens) in addition to slaves. This was an attempt to address the issue of unemployment among Roman citizens and to somewhat curb the dominance of slave labor in agriculture.

- Regulation of Grain Supply: Caesar also focused on ensuring a stable and reliable grain supply to Rome. His intervention in Egypt, securing Cleopatra’s throne, brought that immensely fertile region firmly into Rome’s sphere of influence, ensuring a vital source of grain imports. He also reformed the grain dole (annona) to make its distribution more efficient and reduce abuse.

Farming Practices and Technology

Farming technology in Caesar’s time was largely traditional:

- Plows: Oxen-drawn plows were used, typically light scratch plows that didn’t deeply turn the soil.

- Irrigation: Sophisticated irrigation systems were employed in some regions, especially in drier climates.

- Crop Rotation: Basic forms of crop rotation (e.g., alternating grain with legumes for soil replenishment) were practiced.

- Tools: Simple hand tools, such as hoes, sickles, and scythes, were commonly used.

- Manuring: Animal manure was used to fertilize fields.

Caesar’s impact on farming was less about introducing new technologies and more about reshaping land ownership patterns and labor practices, attempting to address the social and economic inequalities that were contributing to the Roman Republic’s decline. His reforms aimed to create a more stable class of smallholding farmers and loyal veterans, thereby bolstering his own political base and the overall stability of the Roman state.

Here are images illustrating various aspects of farming during the time of Julius Caesar and the Roman Republic/Empire:

- Roman Farming Methods (Ancient Agriculture): This image illustrates the general agricultural practices and tools employed in ancient Roman farming, highlighting the techniques that underpinned their economy and food supply. http://googleusercontent.com/image_collection/image_retrieval/8275626927389644081

- Roman Peasant Plowing Field: This image depicts a Roman peasant or farmer plowing a field, likely with an ox-drawn plow, a fundamental agricultural activity.

- Roman Harvest (Ancient Tools/Grain): This image shows scenes of harvesting in ancient Rome, including the use of various tools to gather grain and other crops.

- Roman Livestock (Ancient Farm Animals): This image presents various types of livestock that were integral to Roman agriculture, such as cattle, sheep, and goats, providing food, wool, and labor.

- Roman Villa Rustica (Ancient Farm Estate): This image depicts a villa rustica, which was a Roman country estate that often served as the center of an agricultural operation, combining residential and farming functions.

Julius Caesar: Geopolitics

Julius Caesar’s actions profoundly reshaped the geopolitics of the Roman world, transitioning it from a complex, often unstable Republic to a centralized imperial system. His strategies and conquests had far-reaching implications that solidified Roman dominance and laid the groundwork for the future Roman Empire.

Here’s a breakdown of his geopolitical impact:

- Expansion of Roman Territory and Influence:

- Conquest of Gaul (58–50 BC): Caesar’s most significant geopolitical achievement was the systematic conquest of Gaul (roughly modern-day France, Belgium, Switzerland, and parts of Germany). This dramatically expanded Rome’s direct territorial control to the Rhine River, integrating vast new resources, populations, and strategic depth into the Roman sphere. It eliminated a long-standing threat from the north and provided Rome with a huge new tax base and source of manpower.

- Intervention in Britain: His two exploratory expeditions to Britain (55 and 54 BC), though not resulting in permanent conquest, demonstrated Roman power beyond the continent and laid the foundation for future Roman influence in the region.

- Securing Client Kingdoms: He actively managed client kingdoms and alliances on Rome’s borders, such as those with certain Germanic tribes or in the East, to create buffer zones and secure strategic interests without direct annexation.

- Consolidation of Power within Rome:

- Ending the Republic’s Factionalism: Caesar’s victory in the Civil War (49–45 BC) eliminated his primary rivals (Pompey and the Optimate faction) and brought an end to the destructive internal civil wars that had plagued the late Republic. His ultimate concentration of power, culminating in his dictatorship for life, effectively ended the complex, often gridlocked system of senatorial rule.

- Centralization of Authority: Caesar centralized decision-making and administrative power, laying the groundwork for the more autocratic rule of the Roman Empire. This streamlined governance allowed for more rapid responses to challenges across the vast Roman domain.

- Strategic Control of Key Regions:

- Influence in Egypt: Caesar’s intervention in the Egyptian dynastic dispute between Ptolemy XIII and Cleopatra VII, siding with Cleopatra, brought the wealthy and agriculturally vital kingdom of Egypt firmly into Rome’s political and economic orbit. This secured a crucial grain supply for Rome, reducing its vulnerability to food shortages.

- Mediterranean Dominance: His campaigns, both land and naval, solidified Roman control over the entire Mediterranean basin (Mare Nostrum), ensuring secure trade routes and unchallenged projection of Roman power throughout the region.

- Long-Term Impact:

- Shift to Empire: Caesar’s actions irrevocably shifted Roman governance from a Republic to a centralized imperial system. His adoption of Octavian (later Augustus) ensured his legacy continued, and Octavian shrewdly built upon Caesar’s foundations to establish the Roman Empire.

- Cultural and Administrative Integration: The new territories conquered by Caesar, particularly Gaul, gradually became Romanized, integrating into Roman administration, law, and culture, which had profound long-term effects on the development of Western Europe.

- Precedent for Imperial Ambition: Caesar’s achievements set a powerful precedent for future Roman emperors, who would continue to expand and consolidate the empire based on his model of military conquest and centralized authority.

Here are images related to the geopolitics of Julius Caesar’s era:

- Roman Empire Map: This map illustrates the vast territorial extent of the Roman Republic and its spheres of influence during Caesar’s time, showcasing the geopolitical landscape he operated within.

- Gallic Wars Map: This image specifically highlights the regions and campaigns of Caesar’s Gallic Wars, which significantly expanded Roman territory and influence in Western Europe.

- Roman Republic Expansion Map: This map offers a comprehensive view of the Roman Republic’s expansion over time, situating Caesar’s conquests within the broader historical context of Roman geopolitical growth.

Julius Caesar: Law

Julius Caesar, while not a dedicated legal scholar, initiated significant legal reforms during his dictatorship. His actions were primarily aimed at stabilizing the Roman state, addressing social and economic issues, and consolidating his own power. His legal legacy is most evident in the Julian Calendar and various administrative and social reforms.

Key Legal Reforms and Impact:

- Julian Calendar (45 BC): This is arguably Caesar’s most enduring legal and administrative reform. The old Roman calendar was severely out of sync with the seasons due to its reliance on lunar cycles and irregular intercalations. Working with the astronomer Sosigenes of Alexandria, Caesar introduced a solar-based calendar with a year of 365 days and a leap year every four years. This new calendar, which began on January 1, 45 BC, was far more accurate and became the standard throughout the Roman Empire and much of Europe until the Gregorian reform in 1582. It represents a significant standardization of timekeeping.

- Debt Relief: Roman society frequently grappled with debt crises. Caesar, who himself had incurred massive debts earlier in his career, understood the social unrest this caused. As dictator, he enacted laws to alleviate debt in 48 BC. These measures included:

- Allowing interest already paid on loans to be deducted from the principal.

- Mandating that property accepted for debt repayment be valued at its pre-Civil War prices, which were generally higher than the depressed market rates of the time.

- Reinforcing an older law that limited the amount of cash a creditor could hold, encouraging investment rather than hoarding. These reforms provided significant relief to debtors, though they were unpopular with creditors.

- Land Reform and Veteran Settlement: Caesar continued and expanded the Roman tradition of land distribution, often using state-owned lands or confiscated properties.

- He settled large numbers of his veteran soldiers on agricultural lands, rewarding their loyalty and providing them with a livelihood.

- He also distributed land to the urban poor and landless citizens, aiming to alleviate poverty and unemployment in Rome and its surrounding areas.

- Grain Dole Reform: The grain dole (distributions of subsidized or free grain to the urban poor) was a key component of Roman public welfare, but had become bloated and prone to abuse.

- Caesar reformed the system, drastically reducing the number of recipients from approximately 320,000 to 150,000. He conducted a census to ensure only genuinely needy citizens qualified, making the system more efficient and less burdensome on the state treasury.

- Judicial and Administrative Reforms:

- Judicial Reform: He reformed the judicial system, particularly by altering the composition of juries to reduce the power of corrupt or biased elements.

- Municipal Laws (Lex Julia Municipalis): While not a single complete code, Caesar issued a series of laws that regulated local governments in Italy, providing a more standardized framework for municipal administration.

- Citizenship Expansion: He extended Roman citizenship to various communities outside Italy, particularly in Gaul. This was a significant step towards integrating conquered peoples more fully into the Roman state and legal system.

- Sumptuary Laws: Caesar also attempted to curb excessive luxury and moral decay through sumptuary laws, though these were often difficult to enforce effectively in Roman society.

Caesar’s legal actions were pragmatic, aimed at bringing order, justice, and stability after decades of civil strife. While he did not create a comprehensive, codified legal system akin to Napoleon’s Code, his reforms were vital in transitioning Rome from a chaotic Republic to a more centralized state, laying a foundation that his adopted son, Augustus, would build upon to establish the Roman Empire.

Here are images related to law in Julius Caesar’s time:

- Ancient Roman Law Code Scroll: Although specific scrolls directly attributed to Caesar’s personal laws may be rare, images of ancient Roman legal texts or fragments offer a visual representation of how laws were recorded and preserved. These documents formed the basis of the legal system Caesar operated within and sought to reform.

- Roman Fasces Symbol of Authority: The fasces were a bundle of rods with an axe, carried by lictors, who were attendants to Roman magistrates. It symbolized the magistrate’s power and authority, including the power to inflict corporal and capital punishment. This emblem was a powerful visual representation of Roman legal and executive power.

- Roman Forum Legal Proceedings Depiction: The Roman Forum was the heart of Roman public life, including legal proceedings. Depictions or reconstructions of the Forum often depict areas where courts convened, illustrating the setting for legal actions during the era of Caesar.

Julius Caesar: Politicians

During the time of Julius Caesar, the political landscape of the late Roman Republic was characterized by a complex interplay of powerful individuals, factions, and the broader Roman populace. Caesar himself was a master manipulator of these dynamics.

Key Individuals and Factions

The Roman Republic’s political arena was largely shaped by the rivalries and alliances of ambitious nobiles (the noble elite).

- Caesar’s Allies:

- Marcus Licinius Crassus: An immensely wealthy senator and general, Crassus formed the First Triumvirate with Caesar and Pompey. He provided crucial financial backing for Caesar’s early political career. His influence helped Caesar secure key appointments.

- Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great): Another powerful general and statesman, Pompey was initially Caesar’s son-in-law and a partner in the First Triumvirate. Their alliance allowed them to bypass traditional senatorial opposition. However, their rivalry for ultimate power eventually led to civil war.

- Mark Antony: A highly loyal and capable military commander, Antony was Caesar’s most trusted lieutenant and staunch supporter. He played a vital role in Caesar’s Gallic campaigns and acted as his deputy in Rome during the Civil War.

- Optimates (Conservative Faction): While fundamentally opposed to Caesar’s populist agenda and singular ambition, some individuals within this traditionalist group might have temporarily aligned with him out of political expediency.

- Caesar’s Rivals and Opponents:

- Optimates: This conservative faction of the Senate sought to uphold the traditional power of the aristocracy and feared Caesar’s growing influence and disregard for republican norms. Key figures included:

- Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis (Cato the Younger): A staunch and incorruptible defender of republican principles, Cato was a fierce ideological opponent of Caesar and a leading figure among the Optimates.

- Marcus Tullius Cicero: A renowned orator, lawyer, and statesman, Cicero was a vocal defender of the Republic, though his political stance often shifted. He frequently voiced concerns about Caesar’s authoritarian tendencies.

- Pompey the Great: After the dissolution of the First Triumvirate and the death of Crassus, Pompey aligned with the Optimates, becoming Caesar’s primary adversary in the Civil War.

- Optimates: This conservative faction of the Senate sought to uphold the traditional power of the aristocracy and feared Caesar’s growing influence and disregard for republican norms. Key figures included:

The Broader Political Landscape

- Senate: The Roman Senate was the Republic’s most influential political body, composed of elite ex-magistrates. While theoretically an advisory body, it wielded immense power, controlling finance, foreign policy, and ultimately, declaring Caesar an enemy of the state. Caesar often sought to dominate or bypass the Senate.

- Populares: Caesar was the leading figure of the Populares faction, which advocated for the rights of the common people (plebs) and challenged the authority of the aristocratic elite. They often used popular assemblies and tribunes to pass legislation, bypassing the Senate. Caesar cultivated immense popularity through public distributions, games, and promises of land reform.

- Equestrians: This wealthy social class, often involved in finance and trade, frequently served as a third force in Roman politics, sometimes aligning with the Optimates and sometimes with the Populares, depending on their economic interests.

- The Roman People (Plebs): The urban plebs, though often impoverished, held significant political power through their votes in the popular assemblies. Caesar was adept at winning their favor through generous handouts and popular reforms, leveraging their support against his senatorial opponents.

- The Army: Crucially, Caesar’s personal army, loyal to him rather than the state, became an unparalleled political force. Their unwavering devotion, earned through shared campaigns, victories, and generous rewards, allowed Caesar to defy the Senate and seize power.

Caesar’s genius lay in his ability to understand, exploit, and ultimately transcend these political relationships, using a combination of military might, popular appeal, and strategic alliances to become the singular dominant figure in the Roman world.

Here are images of key political figures from Julius Caesar’s era:

- Cicero: A renowned orator, lawyer, and statesman, known for his defense of the Roman Republic.

- Cato the Younger: A staunch defender of republican ideals and a fierce opponent of Caesar.

Julius Caesar: Religion

Julius Caesar’s relationship with Roman religion was both traditional and pragmatic, reflecting the Roman approach to deities and rituals as integral to the state’s well-being and a tool for political advancement.

Key Aspects of Caesar’s Religion:

- Pontifex Maximus: Caesar’s most direct and significant involvement in Roman religion was his election as Pontifex Maximus (chief high priest) in 63 BC. This was a powerful, lifelong political-religious office that oversaw state cults, managed religious rites, appointed lower priests, and interpreted divine law. This position gave him immense influence and prestige, which he skillfully leveraged in his political maneuvering.

- Traditional Practices: Despite his political pragmatism, Caesar meticulously upheld traditional Roman religious practices. He participated in public sacrifices, consulted auguries (interpreters of omens from bird flights), and observed religious festivals. Romans believed that maintaining the pax deorum (peace of the gods) through proper ritual was essential for the prosperity and stability of the state.

- Divine Claims and Propaganda: Caesar famously enhanced his political legitimacy by emphasizing his family’s (the gens Julia) mythical descent from the gods. They claimed direct lineage from Iulus, the son of the Trojan prince Aeneas, who in turn was the son of the goddess Venus. Caesar frequently invoked Venus, dedicating temples to her (like the Temple of Venus Genetrix in his forum) and even displaying her image on his coinage. This association with divinity provided a powerful propaganda tool, elevating his status above mere mortals.

- Pragmatism and Manipulation: Caesar was not deeply pious in a personal, spiritual sense; his approach to religion was largely utilitarian. He understood that religious beliefs and institutions were powerful forces in Roman society that could be used for political advantage. He was known to:

- Interpret Omens Conveniently: Use or dismiss omens and prophecies as they suited his political or military goals.

- Assert Authority over Priests: As Pontifex Maximus, he wielded significant control over the priestly colleges.

- Integrate Religion into Statecraft: His reforms, such as the Julian Calendar, had religious implications as they regulated the dates of festivals and public life, further solidifying state control over religious practice.

- Religious Toleration (Limited): While focused on traditional Roman cults, Caesar generally practiced a degree of religious toleration within his conquests, as long as it did not threaten Roman authority. He did not typically force conquered peoples to abandon their local deities, preferring to incorporate them into the broader Roman religious framework or simply demand political loyalty.

Legacy:

Caesar’s use of religion laid important groundwork for the future Roman Empire. His posthumous deification as Divus Iulius (the Divine Julius) by the Senate in 42 BC, spearheaded by Octavian, set a crucial precedent for the imperial cult, where emperors could be worshipped as gods after their death. This reinforced the divine legitimacy of the new imperial system and the ruling family.

Here are images related to religion in Julius Caesar’s time:

- Roman Gods and Goddesses Statues: Roman religion was polytheistic, with a pantheon of gods and goddesses often equated with Greek deities (e.g., Jupiter/Zeus, Juno/Hera, Mars/Ares). Statues like these were central to their worship and public life.

- Roman Priests, Augurs, and Pontifex Maximus: Religious life in Rome was highly organized. Priests held significant political and social power. The Pontifex Maximus was the chief high priest of the College of Pontiffs, a position Julius Caesar himself held, demonstrating the intertwining of religion and politics. Augurs interpreted omens from the flight of birds to guide public actions.

- Roman Temple Architecture: Temples were focal points of Roman religious practice, dedicated to various deities. Their architecture reflected Roman engineering and artistic prowess, providing spaces for rituals and offerings.

Julius Caesar: Rich and Poor

Julius Caesar’s political career was deeply intertwined with the economic and social disparities between Rome’s rich and poor. He skillfully leveraged the grievances of the plebeian class to gain power, while simultaneously navigating and, at times, clashing with the entrenched interests of the wealthy elite.

The Rich (Nobles and Equites)

The “rich” in Caesar’s Rome primarily consisted of two main groups:

- The Patricians/Senatorial Class (Nobles): These were the old aristocratic families who formed the core of the Roman Senate. They controlled vast tracts of land (often worked by slaves), held the highest political offices, and commanded significant military influence. They often viewed themselves as the traditional guardians of the Republic and its customs (mos maiorum). Many of them feared Caesar’s popular appeal and dictatorial tendencies, seeing him as a threat to their collective power and the existing social order. They were largely the creditors whom Caesar’s debt reforms would displease.

- The Equites (Equestrians): This class was generally wealthier than the average citizen but often lacked the ancient lineage of the patricians. They made their fortunes primarily through commerce, finance (e.g., as argentarii or moneylenders), and especially as publicans (tax farmers, who collected taxes in the provinces). They wielded significant economic power and often sought political influence that sometimes aligned with the Senate, and at other times with popular leaders who could protect their business interests. Caesar often relied on their financial support and their votes in the Popular Assemblies.

Caesar’s relationship with the rich was complex. He needed their financial backing and political support early in his career, forming the First Triumvirate with the enormously wealthy Crassus and the influential Pompey. However, as his power grew, he increasingly challenged the Senate’s authority, alienating many traditional nobles who feared his ambition. His debt reforms and populist land distributions directly impacted the wealth and power of some elites. Ultimately, his perceived monarchical aspirations led a faction of wealthy senators to orchestrate his assassination.

The Poor (Plebeians and Proletariat)

The “poor” in Rome encompassed a large and diverse group:

- Urban Plebeians/Proletariat: These were the free citizens living in Rome, often unemployed or underemployed. They relied on sporadic labor, patronage, or the state’s grain dole for survival. They lived in crowded, often unsafe, multi-story apartment blocks (insulae). This group was numerous and highly volatile, capable of significant political agitation if their grievances were ignored. They were the primary beneficiaries of Caesar’s populist appeals and reforms.

- Landless Peasants/Rural Poor: Many former small farmers had lost their lands to larger aristocratic estates (latifundia), often worked by slaves, and had migrated to the cities, exacerbating urban poverty. These individuals were eager for land reform.

- Veterans: Soldiers, often from humble backgrounds, who had served Rome faithfully but returned home to find no land or means of support. Their loyalty was a powerful political tool for generals who promised them land, such as Caesar.

Caesar’s political strategy heavily leveraged the discontent of the poor:

- Grain Dole Reform: He reformed the bloated and inefficient grain dole, reducing the number of recipients but making the system more organized and ensuring that those truly in need received support. This provided basic food security for many.

- Land Distribution: He famously distributed public lands (or confiscated lands from his enemies) to his veteran soldiers and to the urban and rural poor. This was a critical measure that addressed a fundamental economic grievance and secured him immense loyalty from the lower classes.

- Debt Relief: His debt reform laws aimed to alleviate the crushing burden of debt on the lower and middle classes.