The Marble Mines of Carrara, Italy: A Legacy of Timeless Beauty

View of Carrara; the white on the mountains behind is quarried faces of marble (Wiki Image).

A Carrara marble quarry (Wiki Image).

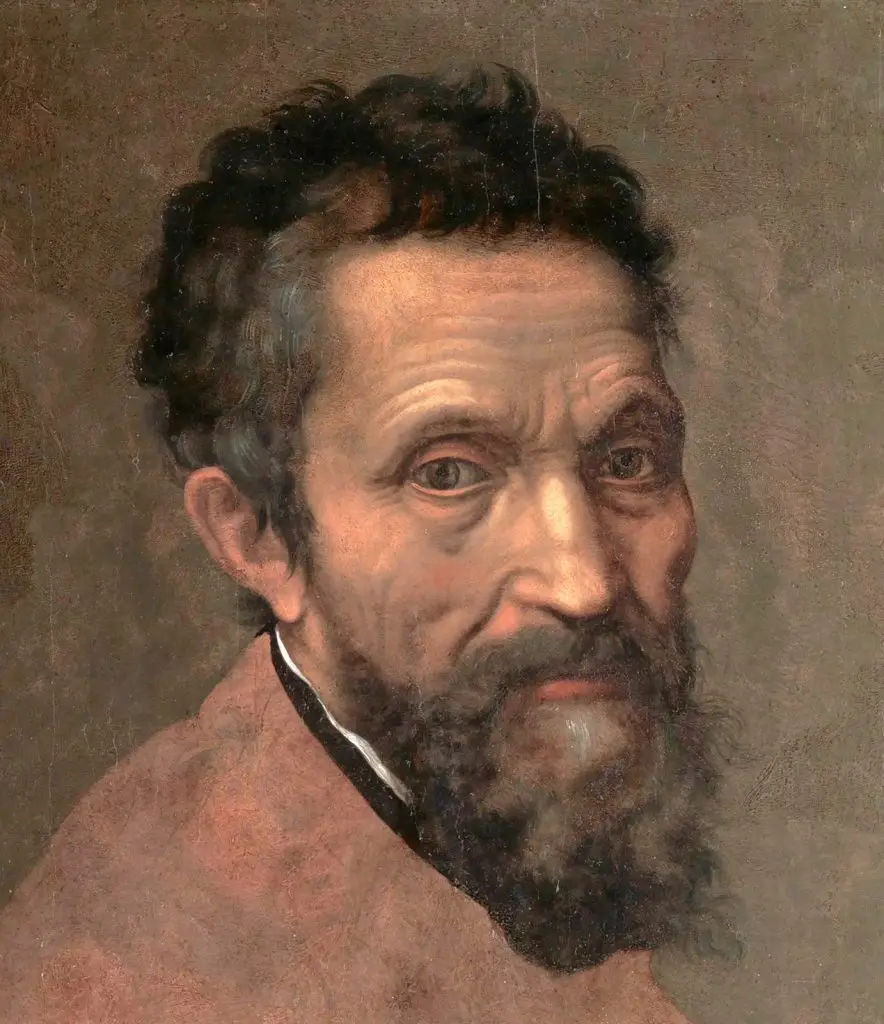

Michelangelo Buonarroti

“The best artist has no conception that a single block of marble does not contain within itself.”

— Michelangelo often traveled to Carrara to personally select marble for his sculptures, emphasizing the importance of the raw material to the final artistic vision.

Giorgio Vasari

“The marbles of Carrara have been the most beautiful of all marbles for centuries… Michelangelo used to spend months among these mountains choosing blocks.”

— Vasari, in Lives of the Artists, describes Michelangelo’s close relationship with the Carrara marble mines.

Antonio Canova

“Carrara marble is the most perfect in the world for sculpting the human figure; its purity allows for the finest detail, giving life to stone.”

— Canova, one of the greatest neoclassical sculptors, praised the unmatched quality of Carrara marble.

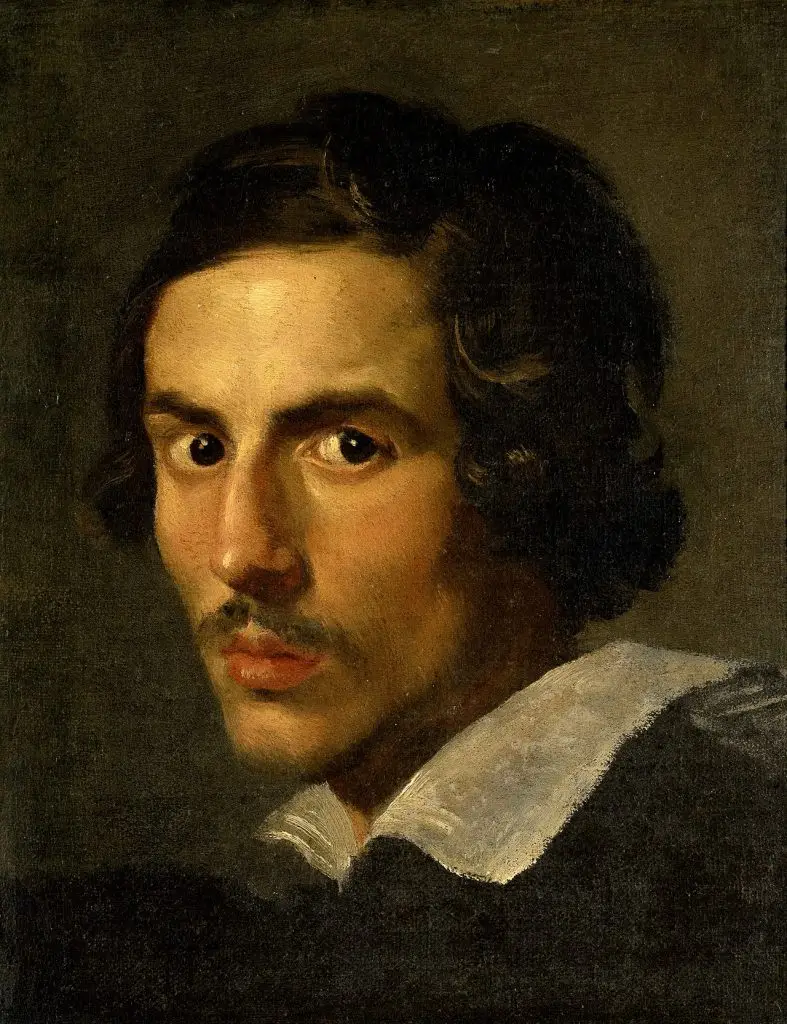

Gian Lorenzo Bernini

“The marble speaks when it is from Carrara, and it is my duty to listen and shape it according to what I hear.”

— Bernini, known for his dynamic baroque sculptures, believed that the unique characteristics of Carrara marble enabled his figures to come alive.

Charles Dickens

“The quarries of Carrara are magnificent and desolate… from these pure hills of marble has been hewn the art of Italy.”

— The famed author commented on the beauty and ruggedness of Carrara during his travels through Italy.

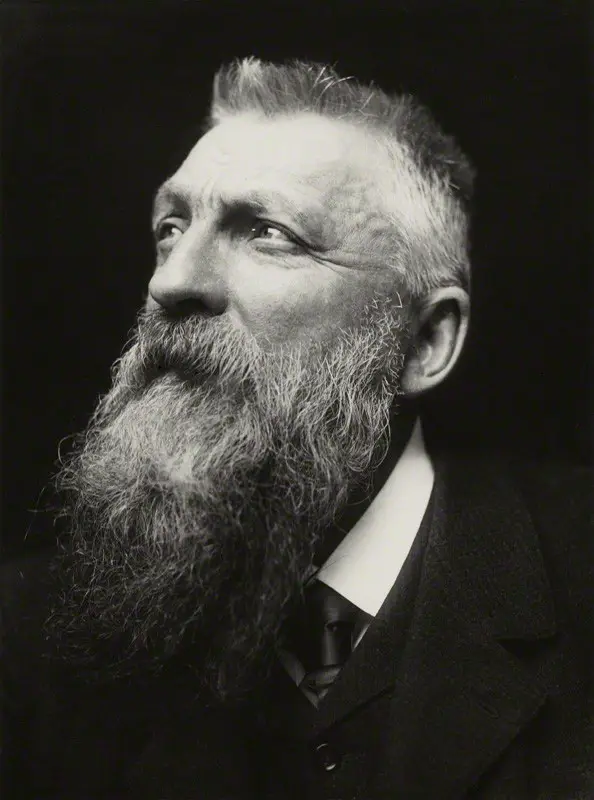

Auguste Rodin

“Carrara marble is not just stone; it is flesh under the sculptor’s hand, capable of capturing emotion and movement.”

— Although Rodin mostly worked in bronze, he admired Carrara marble for its tactile qualities and expressive potential.

Benvenuto Cellini

“The marble quarries of Carrara have yielded the most precious material, which, in the right hands, is capable of miracles.”

— Renaissance artist Cellini recognized the transformative power of Carrara marble in the hands of a skilled sculptor.

Leonardo da Vinci

“Carrara stone is the bone of Italy, essential to its greatest works and monumental triumphs.”

— Da Vinci, although better known as a painter and inventor, appreciated Carrara marble’s importance to Italy’s artistic heritage.

Henry Moore

“Working with Carrara marble, you feel the history of those who carved before you, as if each block carries the weight of centuries.”

— Modernist sculptor Moore, though primarily known for his bronzes, acknowledged the deep history tied to Carrara marble.

Pliny the Elder

“Carrara marble, from the mountains of Luna, shines with the whiteness of the stars, revered by emperors and gods alike.”

— The Roman author and naturalist praised Carrara marble’s beauty and use in ancient Roman sculpture and architecture.

Inside Italy’s $1 Billion Marble Mountains

“ll Capo” (The Chief): a striking look at marble quarrying in the …

ROCKY’S ITALY: Carrara – The Marble Quarries

(YouTube video)

The marble mines of Carrara, located in the Apuan Alps of northern Tuscany, Italy, are world-renowned for producing some of the finest marble in history. This marble, known for its brilliant white color and fine grain, has been a prized material for sculptors, architects, and builders for over 2,000 years. The Carrara quarries have supplied marble for many of the most famous works of art and architecture, including masterpieces by Michelangelo, Bernini, and Canova and iconic structures like ancient Roman buildings and modern landmarks.

Historical Origins

The use of Carrara marble dates back to Roman times when it was extensively quarried to build monuments, temples, and public buildings throughout the Roman Empire. The quarries were first opened around the 1st century BCE under Julius Caesar’s reign, and the marble was used to construct buildings such as the Pantheon and Trajan’s Column in Rome. Its exceptional quality made it a favorite of Roman emperors and elites, and its reputation as one of the world’s best marble sources has persisted ever since.

Geological Characteristics

Carrara marble is a metamorphic rock formed from limestone that underwent intense heat and pressure over millions of years, resulting in its characteristic fine grain and bright, uniform white color. While there are variations in shade, from pure white to blue-gray veining, the purity of Carrara marble has made it especially prized for sculptures and architectural projects that demand a refined finish. Its ability to hold intricate details and polish to a smooth sheen distinguishes it from other types of marble.

Carrara Marble in Renaissance Art

During the Italian Renaissance, the Carrara quarries reached their peak of fame, supplying marble to the greatest artists. Michelangelo was one of the most famous sculptors to use Carrara marble, traveling personally to the quarries to select blocks for his masterpieces, including David and the Pietà. Michelangelo’s use of Carrara marble helped cement its status as the ideal medium for fine art, owing to its workability and aesthetic qualities. His reverence for the marble is evident in his belief that the figure was already “trapped” inside the stone, waiting to be released through carving.

Quarrying Techniques

For centuries, quarrying Carrara marble was a dangerous and labor-intensive process. Workers used traditional methods, such as hand tools like hammers and wedges, to extract large blocks of marble from the mountainside. These blocks were transported by oxen or floated down rivers to be processed and shipped to their final destinations. Over time, technology advanced, introducing wire saws and diamond-tipped cutting tools, making the extraction process more efficient and safer. Modern machinery has transformed quarrying into a highly mechanized process, allowing more extensive and precise marble blocks to be extracted.

Artistic Legacy

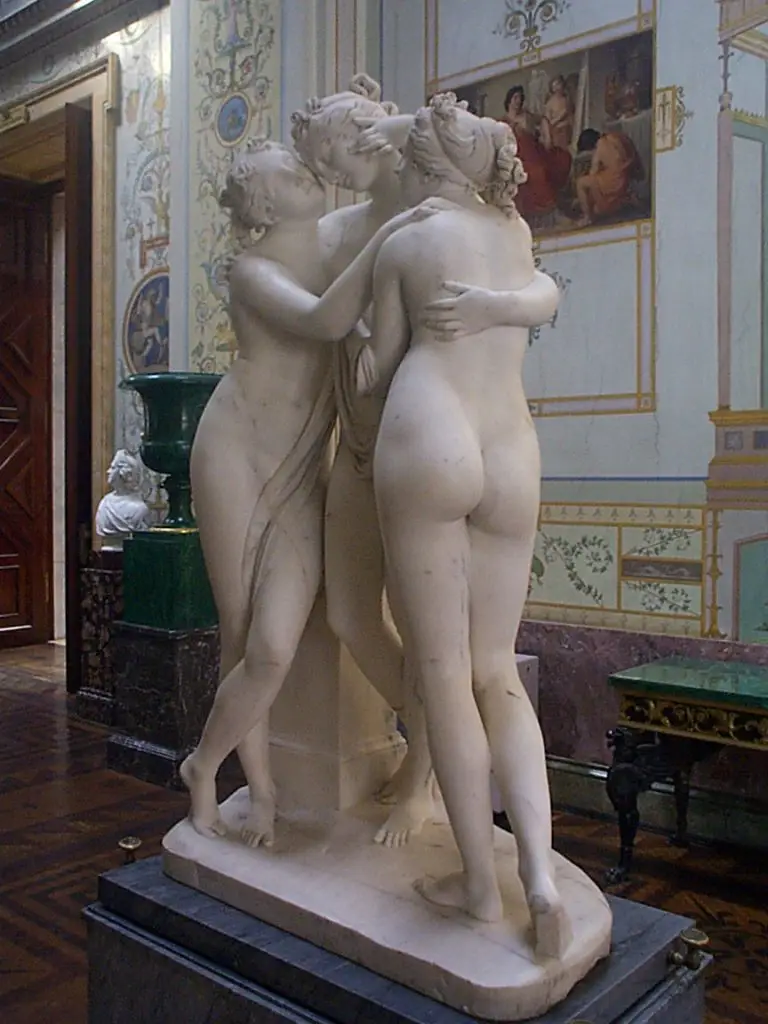

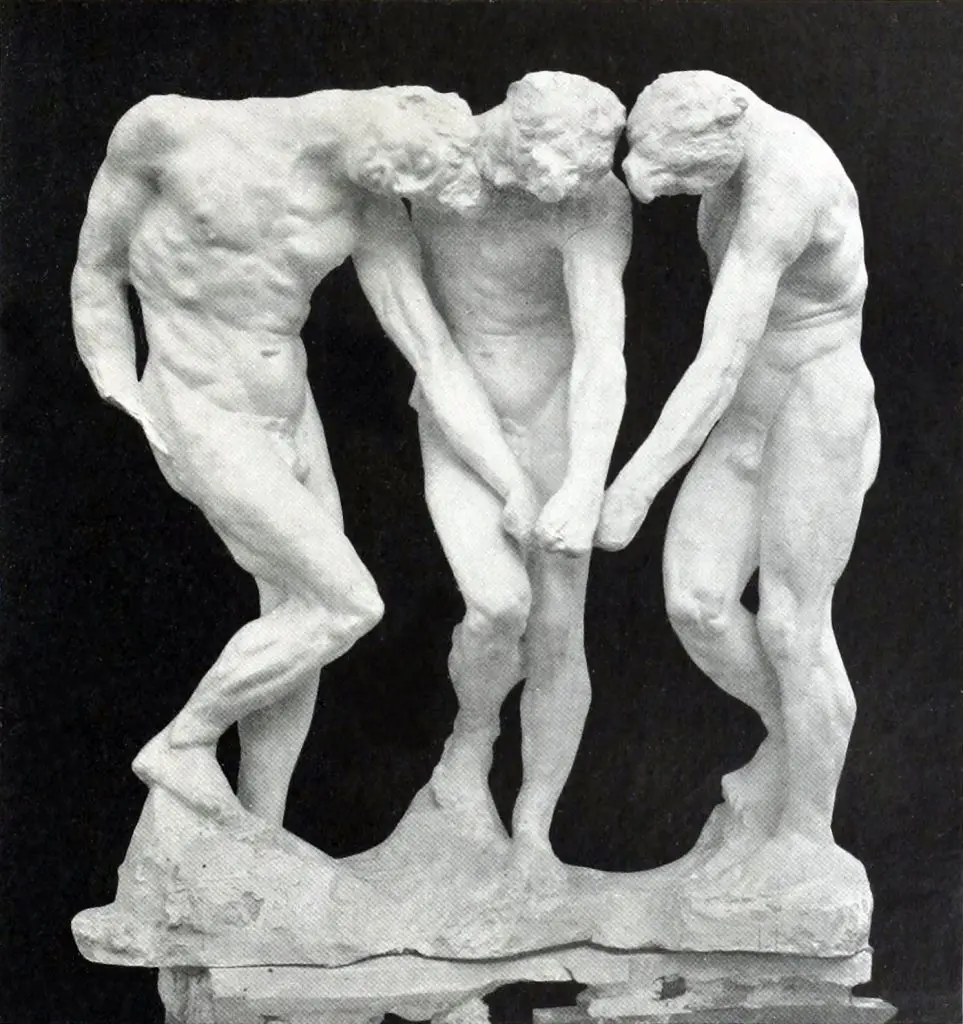

Carrara marble’s legacy in art extends far beyond the Renaissance. In the 18th and 19th centuries, neoclassical sculptors such as Antonio Canova and Bertel Thorvaldsen used Carrara marble to create elegant, idealized forms that paid homage to the classical past. Canova’s The Three Graces and Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss are iconic examples of Carrara marble’s ability to convey softness, beauty, and human emotion. The purity of the marble allowed these artists to achieve a level of detail and refinement that enhanced the emotional depth of their work.

Global Impact on Architecture

Carrara marble has also played a significant role in global architecture. It has been used in major construction projects around the world, from ancient Roman buildings to modern landmarks such as the Marble Arch in London and the United States Capitol building in Washington, D.C. Its durability, elegance, and classic beauty have made it a symbol of luxury and grandeur in architectural design. Today, Carrara marble continues to be a popular choice for interior and exterior design in high-end buildings, as well as countertops and flooring in private residences.

Modern Quarrying and Sustainability

In recent years, there has been increased awareness of the environmental impact of quarrying Carrara marble. The intensive extraction processes can cause significant landscape degradation, and concerns about sustainability have led to the implementation of stricter regulations and more sustainable practices in quarry management. Many quarries now focus on minimizing waste and reducing environmental damage while exploring new methods for restoring exhausted quarry sites. Despite these challenges, Carrara marble remains in high demand, and quarrying remains a significant industry in the region.

Enduring Significance

The marble mines of Carrara continue to symbolize Italy’s rich cultural and artistic heritage. Carrara marble has been associated with beauty, craftsmanship, and artistic excellence for centuries, and its legacy endures in both classical and contemporary art and architecture. Whether used in Michelangelo’s sculptures, modern buildings, or luxury home design, Carrara marble retains its status as one of the world’s finest and most sought-after materials. From ancient Rome to modern times, its story is a testament to the enduring appeal of natural beauty and human creativity.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Antonio Canova, Donatello, and Auguste Rodin: Mable Mines of Carrara Italy

The marble mines of Carrara, Italy, have been a significant source of high-quality marble for centuries and played an essential role in the work of many renowned sculptors, including Michelangelo Buonarroti, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Antonio Canova, Donatello, and Auguste Rodin. Here’s how these sculptors relate to the famed Carrara marble:

Michelangelo Buonarroti:

One of the most famous users of Carrara marble, Michelangelo personally visited the quarries to select blocks for some of his most iconic works, including the Statue of David and the unfinished Prisoners. His deep connection to Carrara marble is legendary, as he valued its purity and fine grain.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini:

A Baroque master, Bernini also used Carrara marble in many of his dynamic and intricate sculptures. Works like The Rape of Proserpina and Apollo and Daphne showcase his extraordinary ability to manipulate marble into lifelike figures.

Antonio Canova:

A leading figure of Neoclassical sculpture, Canova utilized Carrara marble to achieve a smooth and almost ethereal quality in his statues. Pieces like Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss and The Three Graces highlight his delicate craftsmanship.

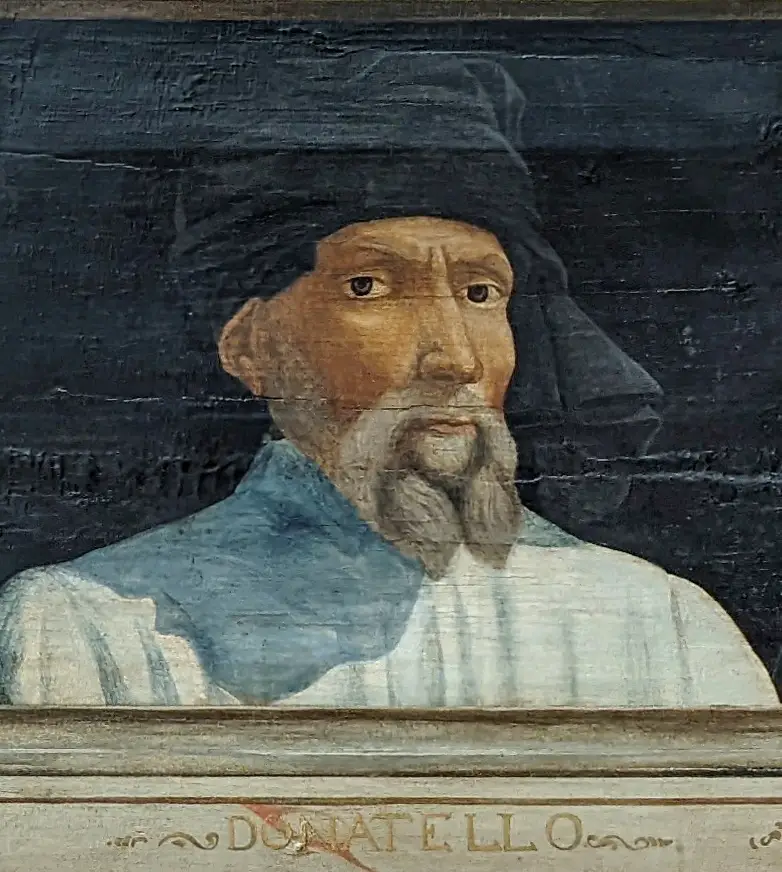

Donatello:

Although Donatello is best known for his work in bronze and other materials, he also worked in marble during the early Renaissance. Carrara marble provided him with a medium for his detailed and expressive sculptures, such as the St. Mark statue.

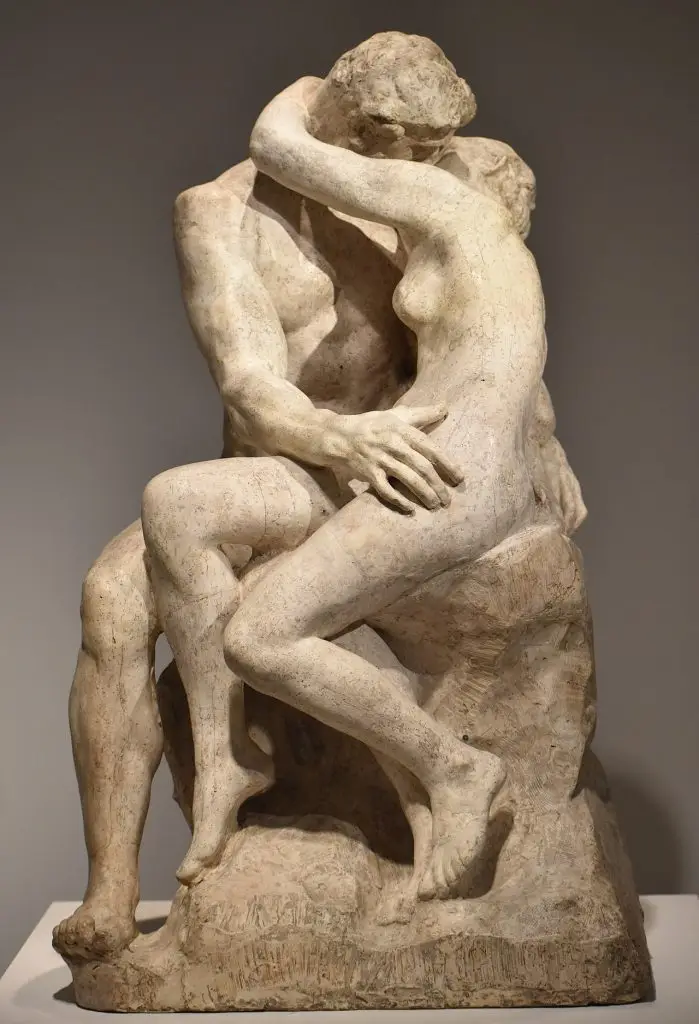

Auguste Rodin:

While Rodin is more closely associated with bronze, he used Carrara marble for some of his works, such as The Kiss. Rodin’s approach to marble was often more rugged and expressive, contrasting with the refined precision of classical sculptors.

Carrara marble is prized for its fine quality and has been sought after since Ancient Rome. Its unique properties allow for the creation of highly detailed and polished sculptures, making it the preferred material for many of history’s greatest artists.

Michelangelo Buonarroti’s History and the Marble Mines of Carrara

Portrait by Daniele da Volterra, c. 1545 (Wiki Image).

“I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.” – This quote captures Michelangelo’s belief that the ideal form already exists within the stone, awaiting the sculptor’s hand to reveal it. It speaks to his profound respect for the material and dedication to uncovering its inherent beauty.

“Every block of stone has a statue inside it, and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.” – This quote further emphasizes Michelangelo’s view of sculpture as a process of revelation rather than creation. It highlights the importance of carefully observing and understanding the marble’s unique qualities to create the hidden masterpiece.

“The best of artists has no conception which a single block of marble does not potentially contain within its mass, but only a hand obedient to the mind can penetrate to this image.” – Here, Michelangelo stresses the connection between the artist’s vision and the physical act of sculpting. The marble holds the potential, but the sculptor’s skilled hand, guided by their imagination, brings the artwork to fruition.

“The more the marble wastes, the more the statue grows.” – This insightful quote reflects the paradox of the sculpting process. As the artist removes material from the block, the form within gradually emerges, revealing its true essence. It speaks to the transformative power of art and the dedication required to achieve perfection.

“A man paints with his brains and not with his hands.” This quote refers to painting and speaks to Michelangelo’s overall artistic philosophy. He believed true artistry lies in conception and vision, translated into reality through skillful execution. This emphasizes the importance of intellectual and creative engagement in the artistic process, even when working with a physical material like marble.

| Sculpture | Year(s) Created | Location | Carrara Marble? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pietà | 1498-1499 | St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City | Yes | Michelangelo’s first major work and his only signed piece. He selected the block in Carrara. |

| David | 1501-1504 | Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence | Yes | This colossal statue, originally intended for Florence Cathedral, is a Renaissance icon. Michelangelo chose a “giant” block from Carrara. |

| Madonna and Child | 1501-1504 | Church of Our Lady, Bruges | Yes | Also known as the Madonna of Bruges. |

| Moses | 1513-1515 | Tomb of Pope Julius II, Rome | Yes | Part of the ambitious (but never fully realized) tomb project. |

| Rebellious Slave | 1513-1516 | Louvre Museum, Paris | Yes | Initially, this unfinished work showcases Michelangelo’s dynamic style for the tomb of Pope Julius II. |

| Dying Slave | 1513-1516 | Louvre Museum, Paris | Yes | Another unfinished figure for the papal tomb conveys a sense of tragic beauty. |

| The Risen Christ | 1519-1521 | Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome | Yes | A less well-known but influential depiction of Christ after the Resurrection. |

| Florence Pietà | 1547-1555 | Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence | Yes | Also known as the Deposition or the Florentine Pietà, this unfinished work was intended for Michelangelo’s tomb. |

Michelangelo: Artist & Genius | Full Documentary | Biography

Michelangelo Explained: From Pietà to the Sistine Chapel

Michelangelo’s David: Great Art Explained

Michelangelo – A Revolution in Art | Documentary

(YouTube video)

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) is universally recognized as one of the greatest artists in history, a sculptor, painter, and architect whose works defined the High Renaissance and set new standards for art. A vital aspect of Michelangelo’s career was his close connection to the marble mines of Carrara, Italy, where he sourced the material for some of his most iconic sculptures, such as the Pietà and David. This relationship between artist and material showcases Michelangelo’s mastery of marble and reflects the centrality of Carrara marble in Renaissance art.

Early Life and Introduction to Sculpture

Michelangelo was born in Caprese, Italy, and raised in Florence, a city that nurtured his artistic talents. As a young apprentice under Domenico Ghirlandaio, Michelangelo learned the basics of painting, but his true passion was for sculpture. It wasn’t long before his talents caught the attention of influential patrons like Lorenzo de’ Medici, who supported his training and exposed him to classical art. Michelangelo’s early fascination with classical sculpture would lead him to work with the most exquisite material available: Carrara marble.

Carrara: The Source of Renaissance Marble

The Carrara marble mines in the Apuan Alps of Tuscany have operated since Roman times, but their fame soared during the Renaissance. The purity and fine grain of Carrara marble made it the material of choice for many of the era’s greatest sculptors. Michelangelo, in particular, was drawn to Carrara because of the quality of its marble, which he believed was the perfect medium for his ambitious projects. He often trips to the quarries to select the blocks he would carve.

The Journey to the Quarries

In 1497, Michelangelo traveled to Carrara for the first time to select the marble for what would become his masterpiece, the Pietà. The journey from Florence to the quarries was arduous, requiring several days of travel over rugged terrain. However, Michelangelo believed that only by personally inspecting the marble could he ensure its quality. He would repeat this journey several times throughout his career, developing an intimate understanding of the material he worked with.

Michelangelo’s Relationship with Marble

Unlike many sculptors, Michelangelo was deeply involved in every stage of his sculptures’ creation, from selecting the marble to the final chiseling. He famously said that he saw the figure “trapped” within the stone and that his job was merely to free it. This artistic philosophy led him to become highly selective in choosing marble blocks. He often rejected pieces with flaws or veins that could interfere with his vision of the final work.

The David: Carrara’s Most Famous Block of Marble

In 1501, Michelangelo undertook one of his most celebrated works: the David. This colossal statue, carved from a single block of Carrara marble, stands over 14 feet tall and remains a symbol of Renaissance art. The block Michelangelo used had a long history—it had been abandoned after an earlier artist deemed it unsuitable. Michelangelo, however, saw potential in the stone and spent over two years meticulously carving the David, which would become one of the world’s most recognized sculptures.

Carrara Marble and the Unfinished Sculptures

Not all of Michelangelo’s projects reached completion, but even his unfinished works highlight his connection to Carrara marble. The Prisoners, a series of unfinished sculptures intended for the tomb of Pope Julius II, show partially completed figures emerging from blocks of Carrara marble. These pieces demonstrate Michelangelo’s belief that the figure was already present within the marble and that his task was to liberate it. The Prisoners’ rough-hewn nature makes the marble visible in the artistic process.

Michelangelo’s Involvement in Quarry Operations

As Michelangelo’s fame grew, so did his involvement with the marble quarries. He was often given the freedom to choose the best marble directly from the mines, a privilege unusual for artists of the time. Michelangelo would sometimes spend months at the quarries, overseeing the extraction of large blocks for his grandiose projects, such as the façade of the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence. This commission was ultimately left incomplete.

The Challenges of Working with Carrara Marble

While Carrara marble was prized for its beauty, it was challenging. Michelangelo often faced difficulties in transporting the enormous blocks of marble from the quarries to his studio, a process that required teams of workers and complex engineering solutions. The journey from Carrara to Florence was treacherous, as the heavy marble had to be transported over mountains and rivers. Michelangelo’s insistence on the highest quality marble made these challenges worthwhile in his eyes.

The Pietà: A Triumph of Marble and Skill

Michelangelo’s early masterpiece, the Pietà, is a testament to his skill with Carrara marble. Carved in 1498-1499, the sculpture depicts the Virgin Mary cradling the body of Christ after the crucifixion. The smooth, flowing lines and lifelike detail of the Pietà exemplify Michelangelo’s mastery of the medium. The marble’s pure white color and fine grain allowed Michelangelo to achieve unprecedented detail, particularly in the delicate features of Christ’s body and Mary’s robes.

Later Years and Ongoing Work with Carrara Marble

In his later years, Michelangelo continued to work with Carrara marble, although he increasingly focused on architectural projects, such as the design of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Despite his shift in focus, he remained deeply connected to the quarries and the material that had defined his career. Michelangelo’s influence on the art world ensured that Carrara marble remained the material of choice for generations of sculptors after him, including Baroque and Neoclassical artists like Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Antonio Canova.

Michelangelo’s Legacy and Carrara Marble

Michelangelo’s legacy is inextricably linked to Carrara marble. His works, particularly the David and the Pietà, stand as monuments to his genius and to the beauty of the material he worked with. Carrara marble became synonymous with the pinnacle of artistic achievement, thanks in no small part to Michelangelo’s unparalleled skill. Even today, the quarries of Carrara remain active, supplying marble for modern artists, but it is Michelangelo’s name that continues to elevate this ancient material in the world’s artistic imagination.

Michelangelo Buonarroti Carrara Sculptures

David (1501-1504)

David (Wiki Image).

The free leg of the contrapposto is in the back view (Wiki Image).

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (German poet and writer)

“Without having seen the Sistine Chapel, one can form no appreciable idea of what one man is capable of achieving, but after seeing David, one knows that Michelangelo is more than human.”

— Goethe’s admiration of David reflects the awe and wonder Michelangelo’s mastery inspired across Europe.

Antonio Canova (Italian Neoclassical sculptor)

“When I saw David, I wept, for I understood at that moment I could never create anything so perfect.”

— Canova, a celebrated sculptor, acknowledged Michelangelo’s unmatched skill after seeing David.

Auguste Rodin (French sculptor)

“Michelangelo’s David is the sculptor’s soul, not the body of a shepherd boy, but a man’s idea of himself.”

— Rodin, one of the greatest sculptors of modern times, saw in David the essence of Michelangelo’s inner artistic vision.

Charles Dickens (English author)

“David represents not just the pinnacle of human physical beauty but also the triumph of intellect and spirit over brute force.”

— Dickens marveled at David’s perfect balance of physical beauty and inner strength.

Pope Julius II

“This work is a testament to the divine spirit within man, to create and to conquer.”

— As a key patron of Michelangelo, Pope Julius II recognized David as a symbol of human ingenuity and divine inspiration.

Michelangelo’s David is one of the most iconic sculptures in art history, representing the pinnacle of Renaissance sculpture. Created between 1501 and 1504, the 17-foot-tall marble statue stands as a symbol of human beauty and strength and the artistic achievements of the Renaissance. Michelangelo’s David differs significantly from earlier depictions of the biblical hero, standing as a unique testament to the ideals of humanism that defined the period.

Commission and Background

The Opera del Duomo originally commissioned the David, the committee overseeing the construction and decoration of the Florence Cathedral. It was intended to be part of a series of large statues representing biblical figures. Michelangelo was given a large block of Carrara marble that had been worked on previously by other artists but left unfinished. Despite these challenges, Michelangelo managed to turn this flawed block of marble into a masterpiece that exceeded all expectations.

Subject and Symbolism

The statue depicts David, the biblical hero who defeated Goliath. However, unlike earlier representations, Michelangelo’s David shows the young hero before the battle rather than after the victory. He is portrayed in a moment of quiet contemplation, his face serious and focused. This decision reflects the Renaissance ideals of humanism, where intellectual power and moral resolve are as important as physical strength. David’s calm yet determined expression symbolizes the triumph of reason and virtue over brute force.

Idealized Human Form

Michelangelo’s David celebrates the human body, representing the Renaissance obsession with classical ideals. The figure’s anatomy is meticulously detailed, with every muscle, tendon, and vein rendered astonishingly. Michelangelo’s understanding of human anatomy gained through his study of cadavers, is evident in the statue’s lifelike realism. David stands in contrapposto, a classical stance where the weight is shifted onto one leg, giving the figure a natural and relaxed posture. This enhances the realism and conveys a sense of potential movement.

Scale and Proportions

At over 17 feet tall, David is much larger than life, emphasizing the monumental nature of the figure. However, when viewed from below, Michelangelo intentionally distorted some of David’s proportions to enhance the statue’s visual impact. The hands, for instance, are disproportionately large, symbolizing David’s future action in defeating Goliath. Similarly, the head is slightly oversized, drawing attention to his focused expression and the intellectual aspect of his character. These distortions, while subtle, contribute to the statue’s powerful presence.

Technical Mastery

The David showcases Michelangelo’s technical brilliance in marble sculpting. Working with a damaged block of marble, he skillfully carved the figure with extraordinary detail and precision. The statue’s surface is polished to a smooth finish, making the marble appear almost flesh-like. Michelangelo’s ability to manipulate light and shadow through the carving enhances the sense of realism and adds depth to the figure. His careful attention to detail, such as the veins on David’s arms and the texture of his hair, sets the sculpture apart as a masterpiece of technical skill.

Public Reaction and Placement

Upon its completion, the David was initially intended for the roofline of the Florence Cathedral, but its beauty and grandeur led to a change in plans. Instead, the statue was placed in front of the Palazzo della Signoria, the seat of Florence’s government, in 1504. It quickly became a symbol of the city, representing the Florentine Republic’s defiance against more powerful states, much like David’s victory over Goliath symbolized the underdog’s triumph. The statue’s placement in a public square made it accessible and solidified its role as a civic symbol.

Cultural and Artistic Significance

Michelangelo’s David is an artistic achievement and a cultural symbol of the Renaissance. It embodies the ideals of humanism, where man is seen as a powerful and capable being. The sculpture emphasizes individual potential, intellectual strength, and moral virtue, which are central to Renaissance thought. Furthermore, David broke away from the medieval tradition of religious art and moved toward a more secular representation of the human condition, reflecting the changing attitudes of the time.

Enduring Legacy

Over the centuries, Michelangelo’s David has remained one of the world’s most revered works of art. It has inspired countless artists and continues to be studied for its technical brilliance and symbolic depth. Today, the original David is housed in the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, attracting millions of visitors annually. The sculpture’s legacy goes beyond its artistic merit; it is a timeless symbol of human achievement, resilience, and the power of the individual to overcome challenges.

Michelangelo’s David remains an enduring masterpiece. It represents the apex of Renaissance art and continues to inspire admiration for its beauty, technical mastery, and profound symbolism.

Pietà (1498-1499)

Madonna della Pietà Our Lady of Piety (Wiki Image).

Giorgio Vasari (Italian painter and biographer)

“It is a miracle that a formless block of stone could ever have been reduced to a perfection that nature can scarcely create in the flesh.”

— Vasari marveled at the lifelike perfection of the Pietà, considering it a divine achievement in marble.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (German poet and writer)

“In the Pietà, Michelangelo has captured sorrow, resignation, and beauty, suspended in a moment that transcends human suffering.”

— Goethe admired the emotional depth Michelangelo achieved, seeing the sculpture as a profound expression of human grief.

Pope John Paul II (Polish pontiff)

“The Pietà speaks to us of the suffering of Christ and of the sorrow of his Mother with an eloquence that transcends words.”

— Pope John Paul II saw in the Pietà a universal language of faith and compassion.

Auguste Rodin (French sculptor)

“The Pietà is not only a mother mourning her son; it is the embodiment of maternal grief and divine acceptance, rendered with unmatched tenderness.”

— Rodin recognized Michelangelo’s ability to blend profound emotional themes with sculptural elegance.

Henry James (American-British author)

“The Pietà has an ineffable power; it is both heartbreaking and serene, a blend of sorrow and tranquility that captivates the soul.”

— James appreciated the juxtaposition of pain and peace in Michelangelo’s masterpiece, calling it a deeply moving art.

The Pietà (1498-1499), created by Michelangelo Buonarroti, is one of the most iconic and celebrated sculptures in the history of Western art. Commissioned for the French Cardinal Jean de Bilhères, the sculpture was intended for the cardinal’s funeral monument and was originally placed in St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City, where it remains today. This masterpiece, carved from a single block of Carrara marble, depicts the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Christ after his crucifixion. The Pietà is renowned for its extraordinary detail, emotional intensity, and technical perfection, and it established Michelangelo as one of the foremost artists of the Renaissance.

The Commission and Its Context

Michelangelo was only 23 years old when he was commissioned to create the Pietà. At the time, he was already gaining recognition for his talent, but the Pietà was the first major work that solidified his reputation as a master sculptor. The commission came from Cardinal Jean de Bilhères, who wanted a grand and pious work as his funerary monument. Although it was common during this period for artists to depict the Virgin Mary and Christ together, Michelangelo’s interpretation of the Pietà was unique in its composition and emotional depth.

The Use of Carrara Marble

Michelangelo famously used Carrara marble, which is known for its high quality and fine grain, making it ideal for detailed and polished sculptures. Michelangelo selected the block of marble from the Carrara quarries, ensuring it was free from imperfections and large enough to accommodate his ambitious vision. The purity of the marble enabled Michelangelo to achieve the extraordinary level of detail seen in the Pietà, from the smooth, polished surface of Christ’s skin to the delicate folds of the Virgin’s drapery. Carrara marble’s translucency also helped Michelangelo capture the softness and realism of flesh.

Composition and Proportions

The composition of the Pietà is triangular, with the figure of the Virgin Mary forming a broad, stable base that supports the body of Christ. This geometric balance creates a sense of calm and stability despite the tragic nature of the scene. Michelangelo skillfully manipulated the proportions to enhance the visual impact; while Christ’s body is rendered in natural proportions, Mary’s figure is more significant than life, allowing her to hold the body of her grown son on her lap. This scale manipulation adds to the sculpture’s symbolic and emotional power, emphasizing Mary’s role as a mother.

The Youthful Depiction of the Virgin Mary

One of the most striking features of Michelangelo’s Pietà is his decision to depict the Virgin Mary as a young woman rather than an older figure, as was traditionally done in representations of this scene. Michelangelo later explained that he intended to portray Mary’s eternal purity and beauty rather than focusing on her age. This choice lends the sculpture a serene and timeless quality, aligning with the Renaissance ideals of beauty and idealized form. Mary’s youthful appearance and calm expression contrast with the sorrowful theme of the sculpture, adding a layer of complexity to the emotional tone.

Realism and Idealism

The Pietà is a masterful blend of realism and idealism. Michelangelo’s technical skill is evident in the lifelike depiction of Christ’s body, which appears soft and supple as if it were still warm. The anatomical precision of Christ’s muscles, veins, and limbs underscores Michelangelo’s deep knowledge of the human form, which he gained through studying anatomy. At the same time, the idealized beauty of the figures, particularly the Virgin Mary, reflects the influence of classical sculpture and Renaissance ideals. Michelangelo achieved a delicate balance between portraying a naturalistic scene and elevating it to divine perfection.

Emotion and Serenity

Despite the subject matter—Mary mourning the death of her son—the Pietà conveys a sense of serenity and grace rather than raw grief. Mary’s expression is calm and composed as if she has accepted her son’s fate with quiet dignity. This emotional restraint aligns with Renaissance ideas about the nobility of suffering and the idealization of human emotions. Michelangelo’s depiction of Mary holding Christ’s body suggests a moment of stillness and contemplation, inviting viewers to reflect on the deeper meaning of sacrifice and redemption.

The Drapery and Its Symbolism

The drapery in the Pietà is one of its most remarkable features. Michelangelo carved the folds of Mary’s robes with incredible precision, creating a sense of movement and flow that contrasts with the stillness of Christ’s body. The voluminous folds of the drapery serve both an aesthetic and symbolic purpose: they enhance the visual impact of the sculpture while also symbolizing the weight of Mary’s sorrow. The heavy drapery amplifies the sense of Mary’s burden, both physical and emotional, as she cradles her dead son.

Michelangelo’s Signature

Interestingly, the Pietà is the only work that Michelangelo ever signed. His signature is carved into the sash across Mary’s chest and reads, “Michelangelo Buonarroti, Florentine, made this.” The story goes that Michelangelo overheard visitors attributing the sculpture to another artist, which led him to add his name to the piece. Signing the sculpture declared his authorship and underscored his pride in the work, which he considered one of his finest achievements. The signature itself became part of the artwork’s legend.

Legacy and Influence

Michelangelo’s Pietà immediately and profoundly impacted the art world, elevating him to master sculptor. The sculpture’s technical perfection, emotional depth, and idealized beauty set a new standard for Renaissance art. It influenced countless artists who sought to replicate Michelangelo’s ability to convey physical realism and spiritual grace. Today, the Pietà remains one of the world’s most revered works of art, drawing millions of visitors to St. Peter’s Basilica each year. It is a testament to Michelangelo’s genius and unparalleled skill in working with Carrara marble.

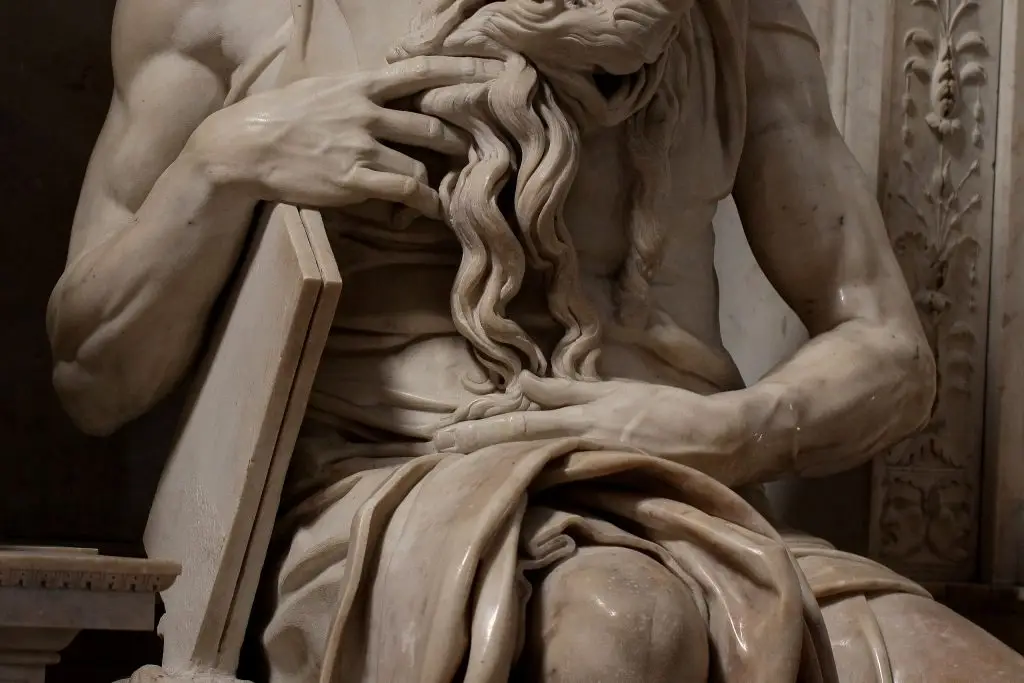

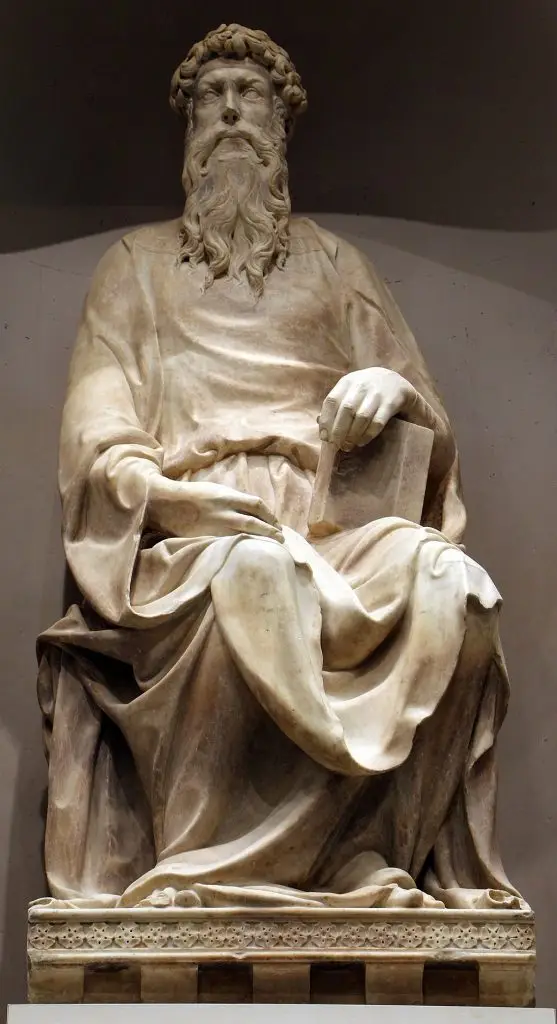

Moses (1513-1515)

Moses (Wiki Image).

Michelangelo’s Moses, detail (Wiki Image).

Sigmund Freud (Austrian neurologist and psychoanalyst)

“Michelangelo’s Moses has an overwhelming power of spirit… a figure in which passion and intellect are held in perfect balance.”

— Freud wrote extensively on Moses, interpreting it as a symbol of human restraint and strength, with the statue embodying deep psychological depth.

Giorgio Vasari (Italian painter and biographer)

“Moses, unlike any other sculpture, seems alive. The tension in his muscles, the force in his expression—Michelangelo gave marble the pulse of life.”

— Vasari praised Moses for its lifelike qualities, particularly the intense realism in the figure’s expression and anatomy.

Auguste Rodin (French sculptor)

“Moses is Michelangelo’s greatest triumph in expressing the divine in human form, capturing the physical power of a prophet and the weight of his burden.”

— Rodin saw Moses as a blend of divine authority and human strength, masterfully carved to communicate force and emotion.

Pope Julius II

“This Moses will be my legacy, as it is the very image of God’s law and man’s defiance brought together in marble.”

— Commissioned by Pope Julius II for his tomb, the sculpture of Moses held great personal and spiritual significance for the Pope.

Rainer Maria Rilke (Austrian poet and novelist)

“The Moses is not a sculpture of stillness, but of motion and energy barely contained… his body prepares to move, his hand tightens, ready for action.”

— Rilke admired the dynamic energy within Moses, viewing it as a figure poised on the verge of action, filled with restrained power.

The Moses (1513–1515), sculpted by Michelangelo Buonarroti, is one of his most iconic works, renowned for its powerful expression and technical brilliance. Originally intended to be part of a grand tomb for Pope Julius II, the sculpture ultimately became the centerpiece of a much smaller monument that now resides in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome. Carved from a single block of Carrara marble, Moses exemplifies Michelangelo’s mastery of anatomy, emotion, and symbolism, showcasing his ability to infuse stone with life-like qualities.

The Commission and the Tomb of Julius II

Michelangelo’s Moses was originally part of a grander plan for the tomb of Pope Julius II, who was one of the artist’s most important patrons. The original design called for an elaborate structure with over 40 statues, intended to be one of the most impressive tombs ever constructed. However, after Julius II died in 1513, the scale of the project was significantly reduced due to financial constraints and political changes in the papacy. Despite the reduced scope, Moses remained the focal point of the monument, symbolizing Julius II’s strength and leadership.

Symbolism of Moses

Michelangelo’s depiction of Moses draws on the biblical story of the prophet receiving the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai. The figure of Moses is seated, yet he exudes a sense of power and readiness, as though he could rise to action at any moment. His intense expression, furrowed brow, and muscular form convey the prophet’s righteous anger after discovering that the Israelites had begun worshipping the golden calf in his absence. This moment of divine wrath is captured in Moses’ pose, with his body tense and gaze focused, giving the sculpture an extraordinary emotional depth.

The Horns of Moses

One of the most distinctive features of Michelangelo’s Moses is the pair of small horns on the figure’s head. This unusual detail originates from a mistranslation of the Hebrew Bible into Latin. The Hebrew word for “rays of light” was mistakenly translated as “horns” in the Latin Vulgate Bible. This led to a tradition of depicting Moses with horns in medieval and Renaissance art. Despite the error, Michelangelo included the horns to symbolize Moses’ divine wisdom and authority, aligning with the medieval interpretation of the prophet as a powerful and enlightened leader.

Michelangelo’s Mastery of Anatomy

The Moses is a testament to Michelangelo’s deep understanding of human anatomy, which he gained through extensive study of the human body, including dissections. Moses’ muscular arms, legs, and torso are sculpted with incredible detail and realism, capturing the tension and power of his body. Every muscle appears to be in a state of readiness, reflecting the intense emotion Moses is experiencing. Michelangelo’s ability to depict such a dynamic figure in a seated position demonstrates his technical skill, as the statue conveys both physical strength and spiritual intensity.

The Drapery and Texture

In addition to the lifelike portrayal of Moses’ body, Michelangelo’s attention to detail extends to the intricate carving of the drapery. The folds of Moses’ robe are masterfully rendered, creating a sense of movement and texture that contrasts with his skin’s smooth, polished surface. The fabric appears to ripple around his body, emphasizing the sense of action and vitality within the figure. The meticulous carving of the drapery also highlights Michelangelo’s ability to manipulate the Carrara marble to achieve different textures and depths, adding to the overall complexity of the sculpture.

Expression and Emotion

Moses’ emotional intensity is one of the sculpture’s most striking features. Michelangelo captures the prophet in a moment of divine wrath, yet there is a sense of restraint in his expression, as if Moses is holding back the full force of his anger. His furrowed brow, pursed lips, and penetrating gaze create a psychological tension that draws viewers into the scene. The sculpture embodies the Renaissance ideal of conveying complex emotions through the human form, and Michelangelo’s Moses stands as one of the most powerful examples of this artistic achievement.

The Role of Carrara Marble

As with many of Michelangelo’s greatest works, the Moses was carved from a single block of Carrara marble. The fine grain of Carrara marble allowed Michelangelo to achieve the delicate details seen in the sculpture, from the texture of Moses’ beard to the veins on his hands. The transparency of the marble also adds to the lifelike quality of the figure, as light interacts with the polished surface to create a sense of warmth and softness despite the hardness of the stone. Michelangelo’s mastery of marble is evident in every aspect of Moses, demonstrating his ability to bring the material to life.

Moses as a Reflection of Michelangelo’s Vision

In many ways, Moses can be seen as a reflection of Michelangelo’s struggles and vision. The intensity of the figure, both physically and emotionally, mirrors the artist’s passionate temperament and deep commitment to his work. Michelangelo was known for his fiery personality and sense of divine mission in his art, embodied in Moses. The sculpture represents a biblical figure and Michelangelo’s vision of human strength, leadership, and the relationship between the divine and the earthly.

Legacy and Influence

Michelangelo’s Moses remains one of the most admired sculptures in Western art history. Its influence can be seen in the work of later sculptors, who sought to emulate Michelangelo’s ability to convey emotion and power through the human form. The Moses continues to captivate viewers with its technical mastery, emotional depth, and symbolic richness. Even today, the sculpture is a testament to Michelangelo’s genius and unparalleled ability to transform marble into a vehicle for human expression and divine inspiration.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s History and the Marble Mines of Carrara

Self-portrait of Bernini, c. 1623, Galleria Borghese, Rome (Wiki Image).

“I do not imitate nature; I compete with her.” – This quote showcases Bernini’s ambition and confidence in his artistic abilities. It implies that he aimed to surpass the beauty and realism of the natural world, a goal achievable with the fine quality of Carrara marble.

“The greatest delight which the soul enjoys in this life is to feel mastered by love.” While not directly about marble, this quote reflects Bernini’s passion and emotional intensity, which is evident in his sculptures. With its ability to capture subtle details and convey drama, Carrara marble was the perfect medium for expressing such sentiments.

“Every block of marble conceals within itself a masterpiece. The task of the sculptor is to release it.” – This quote echoes Michelangelo’s sentiment. Still, Bernini’s dynamic and theatrical style suggests a more active “release” of the form, as seen in his dramatic works like the “Ecstasy of Saint Teresa,” sculpted from Carrara marble.

“I have made statues that speak and weep, that look happy and sad, that express the various passions of the soul.” – Bernini’s sculptures, often carved from Carrara marble, are renowned for their lifelike qualities and emotional expressiveness. This quote speaks to his ability to infuse his works with a sense of movement and drama, making them seem almost alive.

“I have always striven to make marble as pliable as wax.” – This quote highlights Bernini’s technical mastery and his desire to push the boundaries of what was possible with Carrara marble. He sought to transcend the limitations of the material, creating works that appeared impossibly fluid and dynamic.

| Sculpture | Year(s) Created | Location | Carrara Marble? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Goat Amalthea with the Infant Jupiter and a Faun | 1615 | Galleria Borghese, Rome | Yes | Early work showing his emerging talent. |

| Bust of Antonio Coppola | 1612 | San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, Rome | Likely | Bernini’s early patron. Most busts of this period likely used Carrara, though precise documentation can be scarce. |

| The Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence | 1614 | Uffizi Gallery, Florence | Likely | He shows dramatic intensity even in his youth. |

| A Faun Teased by Children | 1616-17 | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York | Yes | Playful and dynamic, highlighting Bernini’s ability to capture movement in stone. |

| Damned Soul | c. 1619 | Palazzo di Spagna, Rome | Likely | Paired with “Blessed Soul,” showcasing contrasting emotions. |

| Blessed Soul | c. 1619 | Palazzo di Spagna, Rome | Likely | |

| The Rape of Proserpina | 1621-22 | Galleria Borghese, Rome | Yes | This is a masterpiece of Baroque sculpture, capturing the dramatic moment of abduction with incredible dynamism and emotion. Bernini specifically sought out Carrara marble for this work. |

| David | 1623-24 | Galleria Borghese, Rome | Yes | A more active and dramatic David than Michelangelo’s, caught in the act of throwing the stone. |

| Apollo and Daphne | 1622-25 | Galleria Borghese, Rome | Yes | This is a breathtaking depiction of transformation, with Daphne turning into a laurel tree as Apollo reaches for her. The delicate details and sense of movement are remarkable. |

| Bust of Cardinal Scipione Borghese | 1632 | Galleria Borghese, Rome | Yes | One of several busts Bernini made of this vital patron. |

| Saint Bibiana | 1624-26 | Santa Bibiana, Rome | Yes | It shows a saint in ecstasy, prefiguring his later work with religious themes. |

| Ecstasy of Saint Teresa | 1647-52 | Cornaro Chapel, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome | Yes | It is a masterpiece of Baroque art, combining sculpture, architecture, and painting to create a theatrical and profoundly emotional experience. |

| Fountain of the Four Rivers | 1648-51 | Piazza Navona, Rome | Yes | A monumental work of urban design featuring personifications of the four major rivers of the world. |

| Truth Unveiled by Time | 1645-66 | Galleria Borghese, Rome | Yes | It is an allegorical work left unfinished but still powerful in its symbolism. |

Gian Lorenzo Bernini: The Baroque Genius Who Redefined …

Bernini Sculptures 👨🎨 Gian Lorenzo Bernini Sculptures …

Great Art Explained: Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne

Bernini, The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa

(YouTube video)

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, a master of Baroque sculpture, is celebrated for his extraordinary ability to transform marble into lifelike figures that defy the material’s natural rigidity. Born in Naples in 1598, Bernini moved to Rome as a child and spent most of his life working in the city, where he became the dominant artistic force of the 17th century. The artistic environment of Rome nurtured his genius, and his connection to the Carrara marble quarries provided him with the raw material necessary to craft his masterpieces. Bernini’s relationship with Carrara marble became essential to his career, enabling him to execute some of history’s most dynamic and emotionally charged sculptures.

Early Life and Training

Bernini was the son of a sculptor, Pietro Bernini, who worked primarily in marble. Gian Lorenzo was exposed to sculpting from a young age and quickly showed an innate talent. By his early teens, he worked on commissions under his father’s guidance. His early works demonstrated a remarkable ability to convey emotion and movement in marble, traits that would define his later works. The Bernini family’s connections to Rome’s artistic and religious elite enabled Gian Lorenzo to gain significant commissions early in his career.

Baroque Sculpture and Bernini’s Vision

Unlike the idealized and static forms of the Renaissance, Bernini’s sculptures were dynamic and full of movement, reflecting the Baroque style’s emphasis on drama, emotion, and theatricality. His works are characterized by a heightened sense of realism, where figures seem to move, breathe, and interact with their surroundings. Carrara marble, known for its fine grain and pure white quality, was the perfect medium for Bernini’s approach to sculpture. Its flexibility allowed him to achieve delicate details and smooth transitions between forms, while its strength enabled the complex compositions he often favored.

Carrara Marble: The Material of Choice

Artists have long prized Carrara marble for its unique properties. Quarried in the Apuan Alps in Tuscany, Italy, Carrara marble is renowned for its pure white color and delicate texture, making it an ideal material for detailed sculpture. Bernini, like Michelangelo before him, recognized the exceptional qualities of Carrara marble and used it extensively in his sculptures. The material allowed him to bring his vision of dynamic, lifelike figures to life, and he was known to be highly selective about the blocks he used, insisting on only the finest quality for his most important commissions.

The Influence of Michelangelo

While Bernini developed his unique style, Michelangelo’s influence was evident in his early works. Michelangelo’s mastery of the human form in marble, particularly his ability to convey strength and emotion, profoundly impacted Bernini. However, Bernini pushed the boundaries further, adding a sense of theatricality and fluidity that went beyond the calm, composed figures of the Renaissance. His ability to make marble appear soft, flexible, and full of motion became his signature, and Carrara marble’s exceptional qualities played a crucial role in achieving this.

Technical Innovations in Marble Sculpting

Bernini’s mastery over marble was not just artistic but also technical. He developed new techniques to manipulate Carrara marble in ways that had never been done before. In works like Apollo and Daphne, Bernini achieved extraordinary detail, where Daphne’s transformation into a tree is depicted with delicate leaves and bark emerging from her skin. The translucent quality of Carrara marble allowed Bernini to suggest the softness of flesh, the texture of hair, and even the fluidity of water. His technical innovations raised the bar for marble sculpture, setting a new standard for future artists.

The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa

One of Bernini’s most famous works, The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647–1652), is a prime example of his use of Carrara marble to create an otherworldly experience. The sculpture, housed in the Cornaro Chapel in Rome, depicts Saint Teresa of Avila in a moment of spiritual ecstasy, visited by an angel holding a spear. Bernini’s skill with Carrara marble allowed him to convey the emotion on Teresa’s face, the delicate folds of her clothing, and the lightness of the angel’s form. The marble seems to dissolve into the air, a testament to Bernini’s technical prowess and ability to manipulate the material.

Apollo and Daphne

Apollo and Daphne (1622–1625), one of Bernini’s early masterpieces, also demonstrates his profound understanding of marble and ability to manipulate it. Carved from Carrara marble, the sculpture depicts the dramatic moment when Daphne is transformed into a laurel tree to escape Apollo’s pursuit. Bernini’s attention to detail is evident in the flowing drapery, the delicate leaves, and Daphne’s expression of terror. Carrara marble’s fine texture enabled him to capture the finest details, from Apollo’s muscular form to the soft bark enveloping Daphne’s skin.

Challenges of Working with Carrara Marble

Working with Carrara Marble was challenging. While prized for its beauty, the material is difficult to work with due to its density and tendency to fracture if handled poorly. Bernini carefully selected his marble blocks to avoid flaws and imperfections that could ruin a sculpture. Despite these challenges, Bernini manipulated the marble with incredible precision, often making it appear like the stone was as soft and malleable as clay. His deep understanding of the material allowed him to push the boundaries of what was possible in marble sculpture.

Bernini’s Relationship with the Marble Quarries

Although Bernini did not personally visit the Carrara marble quarries as frequently as Michelangelo, he maintained close relationships with the quarrymen and stone merchants who supplied him with the best materials. He was known to be exacting in his standards, often rejecting marble blocks that did not meet his specifications. His ability to secure the finest Carrara marble was a testament to his status as one of the most essential artists in Rome, with patrons willing to provide him with the resources necessary to create his masterpieces.

Patronage and Influence

Bernini’s career was marked by close relationships with powerful patrons, including several popes and members of the Catholic Church. These patrons commissioned him to create monumental works carved from Carrara marble. The material’s association with purity and divinity made it a fitting choice for religious art, and Bernini’s sculptures often conveyed a sense of spiritual transcendence. His ability to manipulate marble into lifelike forms helped reinforce the Baroque era’s emphasis on emotional engagement and religious fervor.

Legacy and Influence on Sculpture

Bernini’s use of Carrara marble profoundly influenced the development of Baroque sculpture and beyond. His ability to bring life and movement to marble inspired countless artists in the following centuries. While many sculptors in the 18th and 19th centuries continued using Carrara marble, none could match Bernini’s technical mastery or ability to convey emotion. His works remain some of the most celebrated in art history, and his influence can still be seen in modern sculpture.

Enduring Masterpieces

Bernini’s Carrara marble sculptures, including The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, Apollo and Daphne, David, and The Rape of Proserpina, continue to captivate audiences with their realism, dynamism, and emotional depth. These works, housed in churches and museums throughout Italy, are enduring testaments to Bernini’s genius and unparalleled ability to transform Carrara marble into scenes of intense emotion and beauty. Through his mastery of marble, Bernini ensured that his legacy as one of the greatest sculptors in history would endure for centuries.

In conclusion, Bernini’s use of Carrara marble was integral to his ability to push the boundaries of Baroque sculpture. His technical skill and understanding of the material allowed him to create works as emotionally powerful as they were visually stunning. With its unique properties, Carrara marble became the perfect medium for Bernini to express the drama, emotion, and movement that defined his work.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini Carrara Sculptures

The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647-1652)

Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (Wiki Image).

Gallery (Wiki Image).

“Before the group of the Blessed Ludovica Albertoni, I long remained in contemplation… But in front of the ‘Santa Teresa,’ I was overcome with emotion and wept. This is surely the most beautiful work of art in Rome, perhaps in the whole world. It is the most perfect expression of religious sentiment that it is possible to imagine.” – Stendhal (French writer)

“The beholder is overwhelmed by the intensity of the spiritual experience depicted in the sculpture. The combination of religious ecstasy and physical sensuality is both captivating and unsettling.” – Rudolf Wittkower (German-born art historian)

“Bernini’s ‘Ecstasy of Saint Teresa’ is a masterpiece of Baroque art, capturing the essence of religious fervor and spiritual transcendence. The interplay of light and shadow, the dramatic composition, and the lifelike details create an unforgettable image of divine love.” – The Vatican Museums (Official website)

“Bernini’s sculpture is so vivid that one almost expects the saint to open her eyes and speak. It is a testament to the power of art to evoke profound emotions and convey spiritual experiences.” – Sister Wendy Beckett (British art historian and nun)

“The ‘Ecstasy of Saint Teresa’ is a masterpiece of theatricality and emotional intensity. It is a work that invites the viewer to participate in the saint’s ecstatic experience, blurring the boundaries between the physical and the spiritual.” – Howard Hibbard (American art historian)

The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647–1652) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini is one of Baroque art’s most famous and masterful works. Cardinal Federico Cornaro commissioned it for the Cornaro Chapel in the Santa Maria della Vittoria church in Rome. This sculpture group, depicting the spiritual experience of Saint Teresa of Ávila, embodies the dynamism, theatricality, and emotional intensity characteristic of Bernini’s work and the Baroque period. Bernini combined sculpture, architecture, and painting to create an immersive, dramatic experience for viewers, turning the Cornaro Chapel into a stage for this powerful religious scene.

The Commission and Context

The sculpture was commissioned by Cardinal Federico Cornaro, a member of the wealthy Cornaro family, for his family chapel in Santa Maria della Vittoria. The Baroque period, during which the sculpture was created, was a time of religious renewal in the Catholic Church following the Counter-Reformation. Artists like Bernini were tasked with creating art that inspired deep emotional responses and rekindled faith in the hearts of worshippers. The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa reflects this aim, capturing a moment of intense spiritual experience while evoking the viewer’s awe, devotion, and reverence.

The Subject: Saint Teresa’s Vision

Saint Teresa of Ávila, a Carmelite nun and mystic, wrote extensively about her mystical visions, one of which is depicted in Bernini’s sculpture. In her autobiography, she describes a vision in which an angel pierced her heart with a golden arrow, causing both immense physical pain and spiritual ecstasy. Bernini chose to capture this moment of divine revelation, where the boundaries between physical and spiritual experience blur. Saint Teresa’s expression and posture convey the pain and bliss of this encounter, embodying the intensity of religious devotion.

The Composition and Layout

Bernini’s composition is a masterful blend of sculpture, architecture, and theater. At the center of the chapel, Saint Teresa is depicted reclining on a cloud, her body limp in ecstatic surrender. Above her, an angel holds the golden arrow, poised to strike her heart. The figures are suspended mid-air, creating a sense of weightlessness and divine intervention. The rays of golden light that fan out from behind the figures further enhance the celestial atmosphere, suggesting this is a moment of divine illumination.

The Emotional Expression

One of the defining features of Bernini’s work is his ability to convey intense emotion through the human form, and The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa is a prime example. Saint Teresa’s face is the focal point of the composition, her eyes half-closed and her mouth slightly open, suggesting the overwhelming nature of her experience. Her body is limp, yet her drapery swirls with dynamic movement, contrasting her physical passivity with the spiritual intensity of the moment. The angel, by contrast, is serene and gentle, holding the arrow with a delicate, almost playful touch, emphasizing the divine nature of the encounter.

The Use of Carrara Marble

Bernini carved the figures of Saint Teresa and the angel from the finest Carrara marble, a material prized for its purity and translucency. The marble allowed Bernini to balance realism and idealism, particularly in rendering Saint Teresa’s flesh and the flowing folds of her drapery. The marble seems to come alive under Bernini’s hand, with the soft texture of Teresa’s skin contrasting against the sharp, swirling lines of her garments. Carrara marble’s unique quality of reflecting light helped Bernini create a lifelike appearance that heightens the scene’s emotional impact.

The Integration of Architecture and Sculpture

Bernini was not just a sculptor but also an architect and stage designer, and he brought all of these skills to bear in the creation of The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa. The sculpture is set within a richly decorated chapel Bernini designed to enhance the viewer’s experience. The surrounding architecture frames the sculpture, directing attention toward it as the central focal point. On either side of the chapel, carved reliefs depict members of the Cornaro family watching the scene from their balconies as if they are participants in this divine drama. This theatrical arrangement immerses the viewer in the scene, blurring the line between art and reality.

The Role of Light in the Composition

Light plays a crucial role in the overall composition of The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa. Bernini installed a hidden window above the sculpture, allowing natural light to filter in and illuminate the golden rays behind the figures. This use of light transforms the marble into something ethereal, enhancing the spiritual quality of the scene. The golden rays, made from gilt bronze, shimmer in the light, creating the illusion that the figures are bathed in divine radiance. This clever manipulation of light further underscores the heavenly nature of Saint Teresa’s experience, making the viewer feel like they are witnessing a miracle.

Bernini’s Synthesis of Emotion and Religious Devotion

In The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, Bernini successfully synthesized religious devotion with human emotion in a way that had rarely been seen before. He depicted the mystic’s spiritual experience intensely physically, making her ecstasy palpable to the viewer. The combination of sensuality and spirituality in the sculpture was daring for its time, but it also aligned with the Baroque emphasis on engaging the viewer’s emotions. Bernini’s portrayal of Teresa’s ecstatic vision invites the viewer to contemplate the mystery of divine love and its transformative power, evoking a deeply personal response.

Legacy and Influence

The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa is regarded as one of Bernini’s greatest masterpieces and a defining work of Baroque art. Its influence can be seen in religious and secular art that followed, particularly in its dramatic use of emotion, light, and theatricality. Bernini’s ability to infuse marble with lifelike qualities and spiritual intensity set a new standard for sculpture, and his integration of architecture, sculpture, and light became a hallmark of the Baroque style. Today, The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa inspires awe and devotion, remaining one of the most revered works in art history.

Apollo and Daphne (1622-1625)

Apollo and Daphne (Wiki Image).

Detail of the sculpture (Wiki Image).

“This sculpture is a masterpiece of movement and metamorphosis. Bernini has captured the transformation of Daphne into a laurel tree with incredible detail and emotion.” – Charles Avery, British art historian.

“The interplay between Apollo and Daphne is both beautiful and heartbreaking. Bernini masterfully conveys the tension and drama of the scene.” – Salvatore Settis, Italian art historian.

“The use of Carrara marble in this work is exquisite. It allows Bernini to create a sense of realism and texture that is truly remarkable.” – A.W. Schlegel, German critic and philosopher.

“Apollo and Daphne is a testament to Bernini’s genius as a sculptor. He has transformed a mythological story into a timeless work of art.” – The Louvre Museum, Paris.

“This sculpture continues to inspire awe and wonder in viewers centuries after its creation. It is a true masterpiece of Baroque sculpture.” – The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Apollo and Daphne (1622–1625) is a masterpiece by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, one of the most prominent sculptors of the Baroque period. This marble sculpture depicts the dramatic moment from Greek mythology when the god Apollo, struck by Eros’ arrow, pursues the nymph Daphne, who has been transformed into a laurel tree to escape him. Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne is celebrated for its dynamic composition, intricate detail, and emotional intensity, exemplifying Baroque art’s dramatic flair and technical prowess.

The Mythological Context

The sculpture is based on the mythological tale of Apollo and Daphne from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Apollo, the god of the sun and prophecy, becomes infatuated with Daphne after being struck by one of Eros’ golden arrows, which incites love. Daphne, who is opposed to love and devoted to a life of chastity, is pursued by Apollo. As he catches up to her, she prays to her father, the river god Peneus, for help. In response, she is transformed into a laurel tree just as Apollo reaches her. This moment of transformation is the climax of their myth, capturing the struggle between desire and resistance.

Dynamic Composition

Bernini’s sculpture is renowned for its dynamic and dramatic composition. The figures are depicted in mid-motion, capturing the tension and urgency of the moment. Apollo is shown in the act of reaching out to grasp Daphne, while Daphne’s form is in the process of transforming into a laurel tree. The fluidity and energy of the figures are enhanced by the way Bernini carves the marble, with swirling drapery and twisting limbs creating a sense of movement and struggle. The sculpture’s composition draws the viewer’s eye along the figures’ twisting bodies, emphasizing the narrative’s intensity.

Technical Mastery

The technical skill displayed in Apollo and Daphne is extraordinary. Bernini’s ability to manipulate marble to achieve a range of textures and details is evident throughout the sculpture. The transition from flesh to bark and from a human body to a tree is rendered with remarkable finesse. Daphne’s hair and limbs gradually transform into branches and leaves, with the marble carved so finely that the changes in texture and form are almost imperceptible. Bernini’s attention to detail, from the delicate veins in the leaves to the muscular definition of Apollo’s body, showcases his mastery of the material.

Emotional Intensity

The emotional intensity of Apollo and Daphne is palpable. Apollo’s expression is longing, while Daphne’s face reflects fear and resignation. The sculpture captures the moment of transformation with great sensitivity, conveying Daphne’s pain and helplessness as she is turned into a tree. The contrast between Apollo’s active pursuit and Daphne’s passive resistance enhances the piece’s emotional impact. Bernini’s ability to convey such complex emotions through marble highlights his skill in capturing the psychological depth of his subjects.

Symbolism and Themes

The sculpture explores desire, transformation, and the tension between physical pursuit and spiritual chastity. Apollo’s relentless pursuit symbolizes the power and intensity of physical desire, while Daphne’s transformation into a laurel tree represents her escape from this pursuit and her preservation of virtue. The laurel tree, associated with Apollo in later mythology, symbolizes the god’s unrequited love and the permanence of Daphne’s chastity. Bernini’s depiction of these themes underscores the Baroque interest in capturing dramatic and morally charged narratives.

Baroque Characteristics

Apollo and Daphne exemplify key characteristics of Baroque art, including its emphasis on dramatic action, emotional engagement, and the use of space. Bernini’s use of movement and complex poses reflects the Baroque fascination with dynamism and the capture of decisive moments. The sculpture’s intricate details and expressive forms are designed to engage viewers emotionally, drawing them into the narrative. Bernini’s innovative approach to sculptural composition and his ability to evoke intense feelings are hallmarks of the Baroque style.

Impact and Influence

The impact of Apollo and Daphne on the art world was profound. The sculpture is considered one of Bernini’s masterpieces and a pinnacle of Baroque sculpture. Its innovative use of marble and its dramatic portrayal of mythological subjects influenced later artists and sculptors. The work’s emphasis on movement and emotion set new standards for depicting narrative in sculpture, inspiring subsequent generations of artists to explore similar themes and techniques.

Historical Context

Created in the early 17th century, Apollo and Daphne reflect the cultural and artistic climate of the Baroque period. This era focused on dramatic expression and grandeur and explored complex emotional and spiritual themes. Bernini’s work aligns with the Catholic Church’s desire to evoke profound spiritual experiences and convey religious narratives dramatically. The sculpture was commissioned by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, a patron of the arts and a supporter of Bernini, who sought to enhance his collection with a work that exemplified the Baroque ideal.

Legacy and Preservation

Today, Apollo and Daphne are housed in the Galleria Borghese in Rome, which continues to be celebrated as a masterpiece of Baroque sculpture. The work’s influence extends beyond its immediate context, contributing to Bernini’s art’s broader legacy and sculptural practice’s evolution. Its depiction of the transformative moment and the emotional depth of the figures remain powerful and evocative, ensuring its place as one of the defining works of the Baroque era.

David (1623-1624)

David (Wiki Image).

“Bernini’s David is not a static ideal, but a man in action, caught in the moment of his greatest effort. He is all coiled energy, about to unleash his power against Goliath.” – Howard Hibbard, American art historian.

“Unlike Michelangelo’s contemplative David, Bernini’s is a figure of dynamic action, his muscles straining as he prepares to launch his stone. This sculpture embodies the Baroque spirit, emphasizing movement, drama, and emotional intensity.” – The Guardian, British newspaper.

“Bernini’s David ” is a Baroque sculpture masterpiece, capturing the biblical hero’s tension and dynamism like no other artist. The statue’s dramatic pose and swirling drapery create a sense of movement that draws the viewer into the scene.” – The Borghese Gallery, Rome, Italy.

“This sculpture is not simply a representation of David, but also a self-portrait of the artist, capturing Bernini’s youthful ambition and determination.” – Irving Lavin, American art historian.

“Bernini’s David is a powerful expression of human will and the underdog’s triumph. It is a work that continues to inspire and amaze viewers centuries after its creation.” – The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Bernini’s David (1623–1624) is a striking marble sculpture by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, renowned for its dramatic intensity and innovative portrayal of the biblical hero David. This work represents a significant departure from traditional depictions of the figure, showcasing Bernini’s mastery of dynamic composition and emotional expression. The statue is housed in the Galleria Borghese in Rome and is celebrated as one of the masterpieces of Baroque sculpture.

The Biblical Context

Bernini’s David depicts the moment before the young shepherd David confronts the giant Goliath, capturing the intensity and determination of the hero as he prepares to launch his stone. The biblical story in the First Book of Samuel tells of David’s victory over Goliath, symbolizing the triumph of faith and courage over overwhelming odds. Bernini’s interpretation focuses on the action and emotional stakes of the moment, presenting a dynamic and engaging representation of this well-known narrative.

Dynamic Composition

The sculpture is remarkable for its dynamic composition, which captures David amid the action. Unlike earlier Renaissance depictions of David, which often portrayed him in a calm or contemplative pose, Bernini’s David is shown in a moment of intense physical and emotional engagement. The figure is depicted in a twisted, contrapposto stance, with his body and limbs extended in a powerful, forward-leaning pose. This dynamic arrangement conveys a sense of motion and tension, drawing the viewer into the critical moment of the story.

Technical Mastery

Bernini’s technical mastery is evident in the intricate details of the sculpture. The marble is skillfully carved to convey the texture of David’s hair, the sinews of his muscles, and the folds of his clothing. The precision of the carving allows for a lifelike representation of the figure’s physicality and emotional state. The attention to detail, from the tautness of David’s grip on the sling to the expression of determination on his face, highlights Bernini’s ability to capture his subject’s physical and psychological aspects.

Emotional Expression

One of the most compelling aspects of Bernini’s David is its emotional intensity. David’s face is etched with a look of fierce concentration, while his body language communicates both the weight of the moment and his resolve. The tension in his posture and the determined expression convey the inner turmoil and courage of the hero as he faces his formidable opponent. Bernini’s ability to evoke such a powerful emotional response from a static medium demonstrates his exceptional skill as a sculptor.

Baroque Characteristics

David is a quintessential example of Baroque art, emphasizing movement, drama, and emotional engagement. The sculpture’s dynamic pose and dramatic use of space reflect the Baroque interest in capturing decisive moments and evoking strong emotional reactions. Bernini’s innovative approach to the depiction of narrative and his focus on the psychological depth of his subjects align with the Baroque style’s emphasis on dramatic expression and engagement with the viewer.

Contrast with Renaissance Depictions

Bernini’s David represents a significant departure from the more restrained and idealized Renaissance depictions of the biblical hero. Earlier Renaissance sculptures, such as those by Donatello and Michelangelo, often portrayed David as a calm, contemplative figure, emphasizing his intellectual and moral qualities. In contrast, Bernini’s work focuses on the moment’s physical and emotional aspects, highlighting the narrative’s action and drama. This shift reflects the Baroque era’s fascination with movement and intensity.

Symbolism and Interpretation

Bernini’s David represents a biblical hero and symbolizes the artist’s creative power and ingenuity. The dynamic pose and intense expression reflect overcoming challenges through strength and skill. The sculpture can be interpreted as a metaphor for the artist’s struggle and triumph in the face of artistic challenges, embodying the Baroque ideals of personal and artistic achievement.

Patronage and Context

The sculpture was commissioned by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, a prominent patron of the arts known for his support of Bernini. The work was intended to enhance the cardinal’s art collection and showcase the artist’s ability to bring new life to classical themes. The commission reflects the broader context of the Baroque period, where art was increasingly used to convey dramatic and emotional narratives, often in the service of powerful patrons and institutions.

Legacy and Influence

David stands as a landmark work in the history of sculpture, influencing subsequent generations of artists and shaping the development of Baroque art. Bernini’s innovative approach to composition and emotion set new standards for portraying narrative and character in sculpture. The work remains a powerful example of the Baroque style’s emphasis on movement, drama, and emotional intensity, and it continues to be celebrated for its artistic excellence and impact on the history of art.

Antonio Canova’s History and the Marble Mines of Carrara

Antonio Canova (Wiki Image).

“I love the white light of Carrara marble. It allows me to capture the subtle nuances of the human form and create sculptures that seem to breathe.” – This quote, though attributed to Canova, is likely apocryphal. However, it accurately reflects his deep appreciation for the luminosity and transparency of Carrara marble, which he skillfully utilized to create his masterpieces.

“The sculptor’s art consists in making the stone speak.” – Canova believed that sculpture should convey emotion and tell a story. With its fine grain and ability to capture intricate detail, Carrara marble provided the ideal medium for his expressive works.

“Beauty is the first test: there is no permanent place in the world for ugly mathematics.” – Canova emphasized the importance of aesthetic beauty and harmony in his sculptures, even those based on classical ideals and proportions. Carrara marble’s natural elegance perfectly complemented his artistic vision.

“The artist must work not only with his hands but also with his heart and soul.” – Canova’s dedication to his craft and his pursuit of artistic perfection are evident in his meticulous carving and attention to detail. His sculptures, often created from Carrara marble, are a testament to his passion and commitment.

“The marble of Carrara is like a blank canvas, waiting for the artist’s touch to bring it to life.” – This quote, while not directly attributed to Canova, reflects his approach to sculpture. He saw the potential within the raw material and used his skill and imagination to transform it into works of timeless beauty.

| Sculpture | Year(s) Created | Location | Carrara Marble? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orpheus | 1773-76 | Museo Correr, Venice | Likely | This was part of his first major commission, paired with Eurydice. While early works’ specific marble origin isn’t always documented, Carrara was the predominant source for Venetian sculptors. |

| Eurydice | 1773-76 | Museo Correr, Venice | Likely | |

| Daedalus and Icarus | 1777-79 | Museo Correr, Venice | Yes | Won him early acclaim, showcasing his skill in depicting dynamic figures. |