Excellent! Let’s dive into each of these historical events with a brief overview:

Sicilian Expedition (415-413 BC, Sicily)

- What happened: During the Peloponnesian War, Athens launched a massive expedition to conquer Sicily, aiming to gain resources and weaken Sparta. However, the campaign was plagued by poor leadership, logistical problems, and fierce resistance from Syracuse. The Athenian forces were ultimately trapped and annihilated, marking a turning point in the war and the decline of Athenian power.

- Key takeaway: Overambition and strategic miscalculations can have disastrous consequences, even for powerful empires.

Battle of Cannae (216 BC, Italy)

- What happened: During the Second Punic War, the Carthaginian general Hannibal defeated a much larger Roman army. Hannibal’s brilliant tactical envelopment maneuver led to the near-destruction of the Roman legions, shocking Rome and demonstrating Hannibal’s military genius.

- Key takeaway: Tactical brilliance can overcome numerical superiority, and even the mightiest empires can be vulnerable to strategic innovation.

Teutoburg Forest (9 AD, Germany)

- What happened: A coalition of Germanic tribes, led by Arminius, ambushed and destroyed three Roman legions in the Teutoburg Forest. This devastating defeat halted Roman expansion into Germany and highlighted the challenges of fighting in unfamiliar terrain against determined adversaries.

- Key takeaway: Environmental factors and underestimating the enemy can have disastrous consequences, even for highly disciplined armies.

Battle of Red Cliffs (208 AD, China)

- What happened: An alliance of underdog forces, led by Liu Bei and Sun Quan, decisively defeated the numerically superior army of Cao Cao. Clever tactics, including the use of fire ships and exploitation of wind conditions, secured victory and shaped the course of the Three Kingdoms period in China.

- Key takeaway: Strategic alliances and exploiting environmental conditions can be crucial for overcoming seemingly insurmountable odds.

“Kamikaze” or Divine Wind (1274 & 1281, Japan)

- What happened: Typhoons, known as “kamikaze” or “divine wind,” played a crucial role in repelling two Mongol invasion fleets. These storms were interpreted as divine intervention, bolstering Japanese national identity and contributing to the legend of the kamikaze.

- Key takeaway: Natural events can profoundly impact history and shape cultural narratives.

Battle of Agincourt (1415, France)

- What happened: The English army, led by King Henry V, achieved a stunning victory over a much larger French force. The English longbow proved devastating against the heavily armored French knights, demonstrating the power of technological advantages in warfare.

- Key takeaway: Technological superiority and innovative tactics can overcome numerical disadvantages.

Battle of Tenochtitlán (1521, Mexico)

- What happened: Spanish conquistadors, led by Hernán Cortés, conquered the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán. A combination of superior weaponry, alliances with indigenous enemies of the Aztecs, and disease contributed to the Spanish victory and the fall of the Aztec Empire.

- Key takeaway: Technological advantages, alliances, and unforeseen factors (like disease) can dramatically shift the balance of power.

Battle of Lepanto (1571, Mediterranean)

- What happened: The Holy League, a coalition of European powers, decisively defeated the Ottoman fleet. This victory marked a turning point in the Ottoman advance into Europe and demonstrated the effectiveness of combined naval power.

- Key takeaway: Naval power and strategic alliances can be critical for controlling vital sea lanes and influencing geopolitical dynamics.

Spanish Armada (1588, England Channel)

- What happened: The English navy defeated the Spanish Armada, a massive fleet sent by King Philip II to invade England. English naval tactics and superior gunnery proved decisive, thwarting the invasion and marking a shift in European naval dominance.

- Key takeaway: Naval power and technological innovation can be crucial for national defense and securing maritime supremacy.

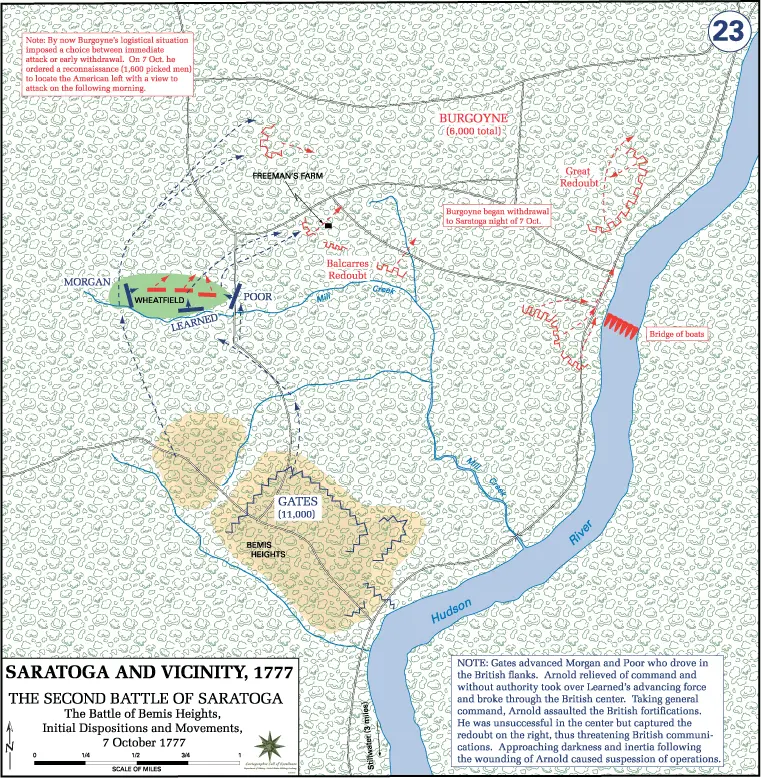

Battles of Saratoga (1777, America)

- What happened: American forces, led by General Horatio Gates, defeated the British army in a series of battles. This decisive victory convinced France to formally ally with the Americans, providing crucial support in the Revolutionary War.

- Key takeaway: Strategic victories can have far-reaching diplomatic consequences and alter the course of revolutions.

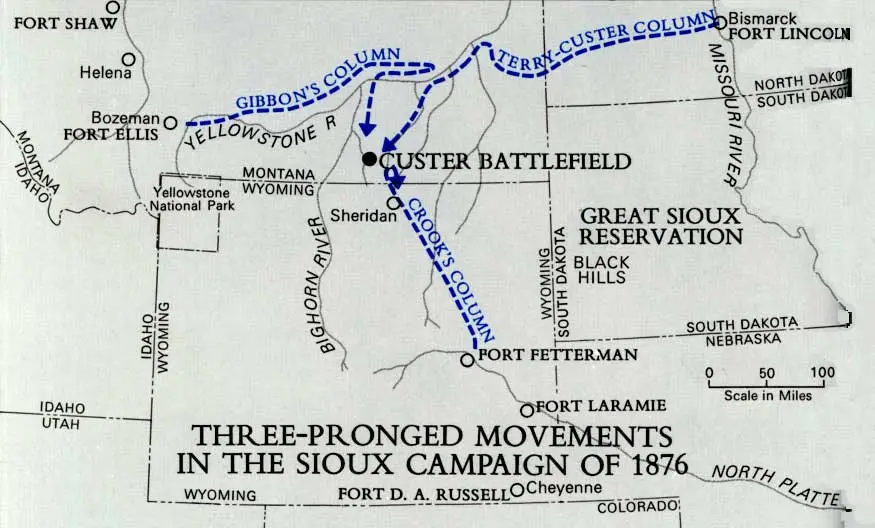

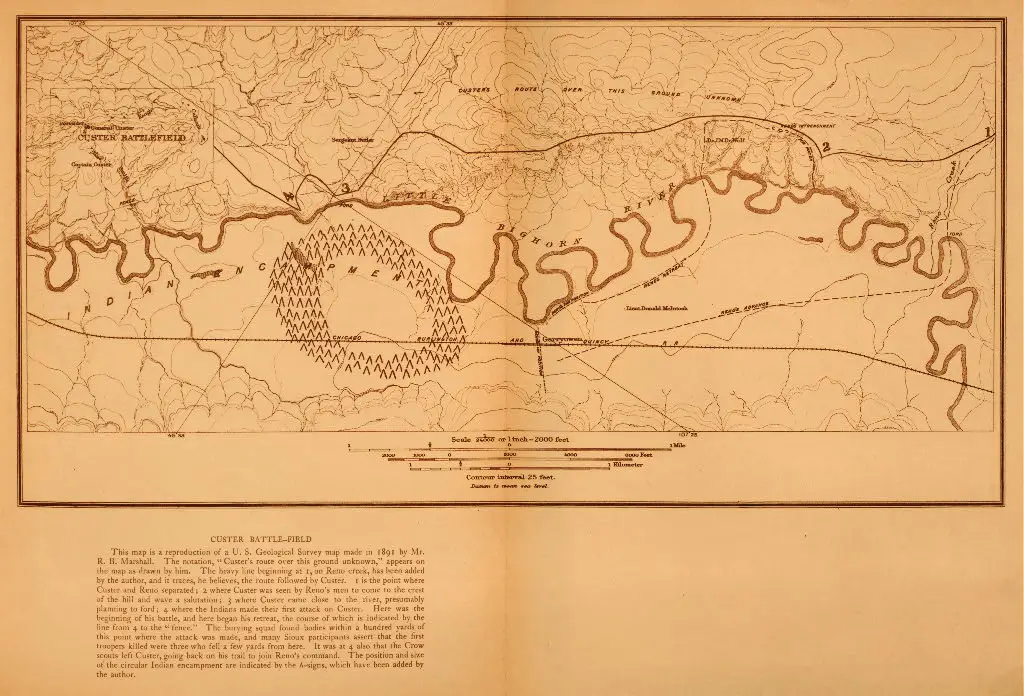

Battle of Little Bighorn (1876, America)

- What happened: Lakota and Cheyenne warriors, led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, annihilated Lieutenant Colonel George Custer’s detachment of the 7th Cavalry. This Native American victory, though temporary, highlighted the resistance to westward expansion and the complexities of the conflict.

- Key takeaway: Underestimating the enemy and disregarding cultural differences can have devastating consequences.

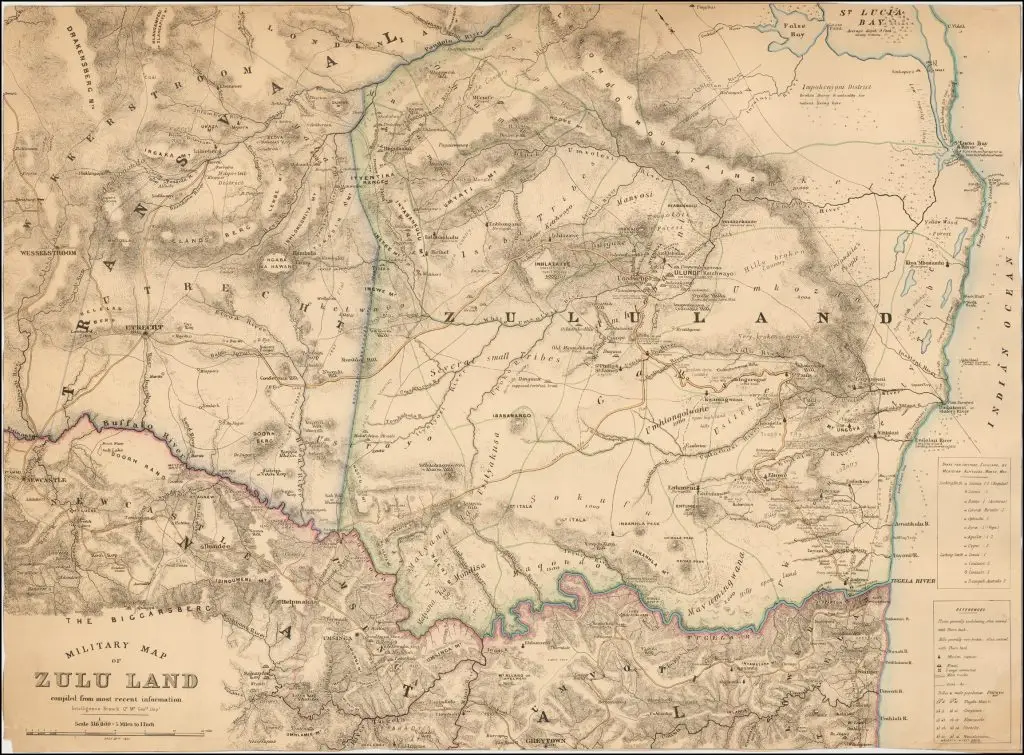

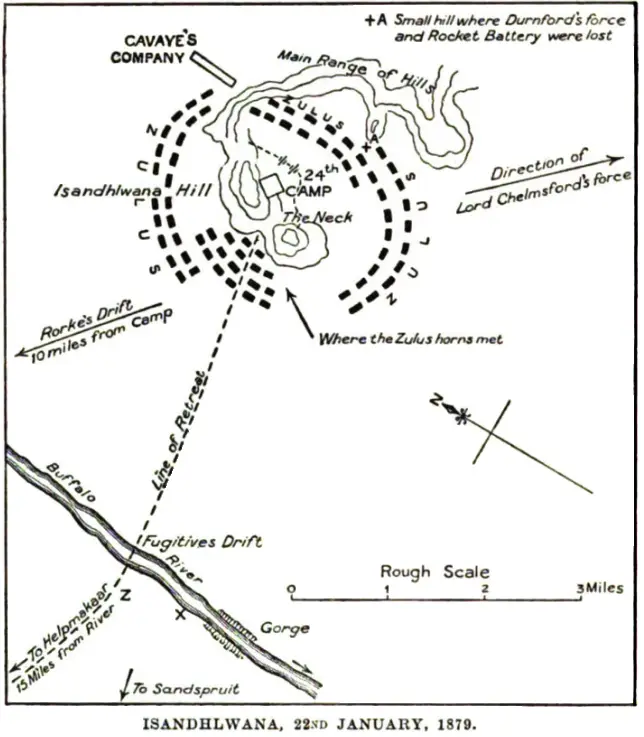

Battle of Isandlwana (1879, South Africa)

- What happened: Zulu forces, armed with spears and shields, decisively defeated a British force. This shocking defeat exposed British vulnerabilities and fueled the Anglo-Zulu War.

- Key takeaway: Even technologically superior armies can be vulnerable to determined resistance and tactical adaptation.

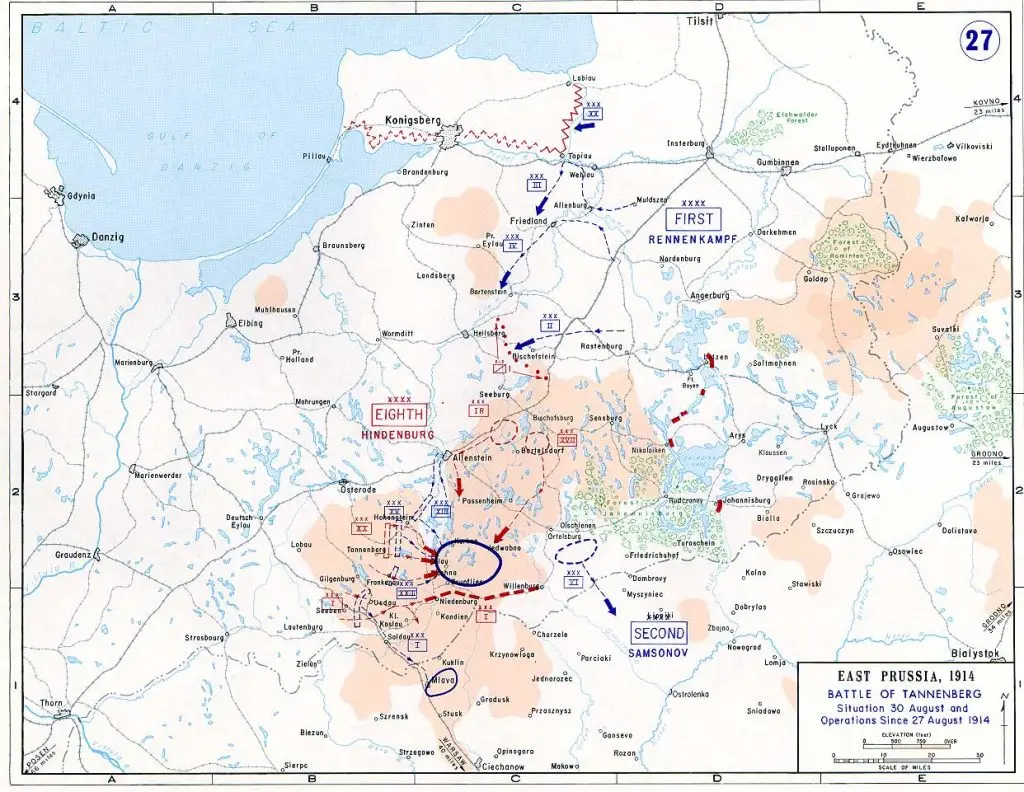

Battle of Tannenberg (1914, East Prussia)

- What happened: The German army, led by Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff, decisively defeated the Russian Second Army. This victory secured Germany’s eastern front in the early stages of World War I.

- Key takeaway: Strategic planning, communication, and decisive leadership can be crucial for success in modern warfare.

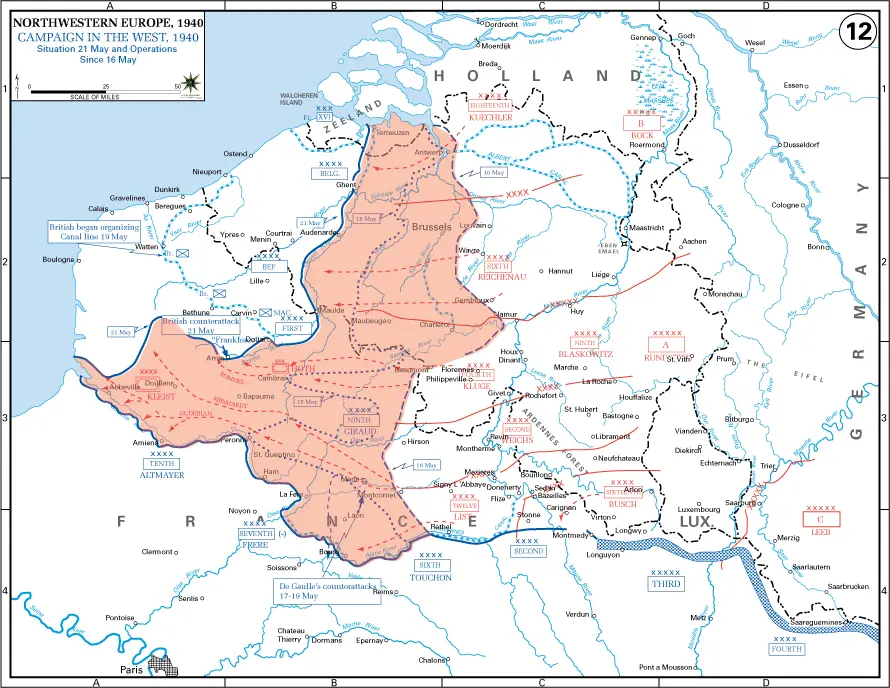

Battle of France (1940, France)

- What happened: German forces, employing Blitzkrieg tactics, swiftly conquered France. The Allied armies were outmaneuvered and overwhelmed, leading to the fall of France and the occupation of much of Western Europe.

- Key takeaway: Technological innovation, operational boldness, and strategic surprise can lead to rapid and decisive victories.

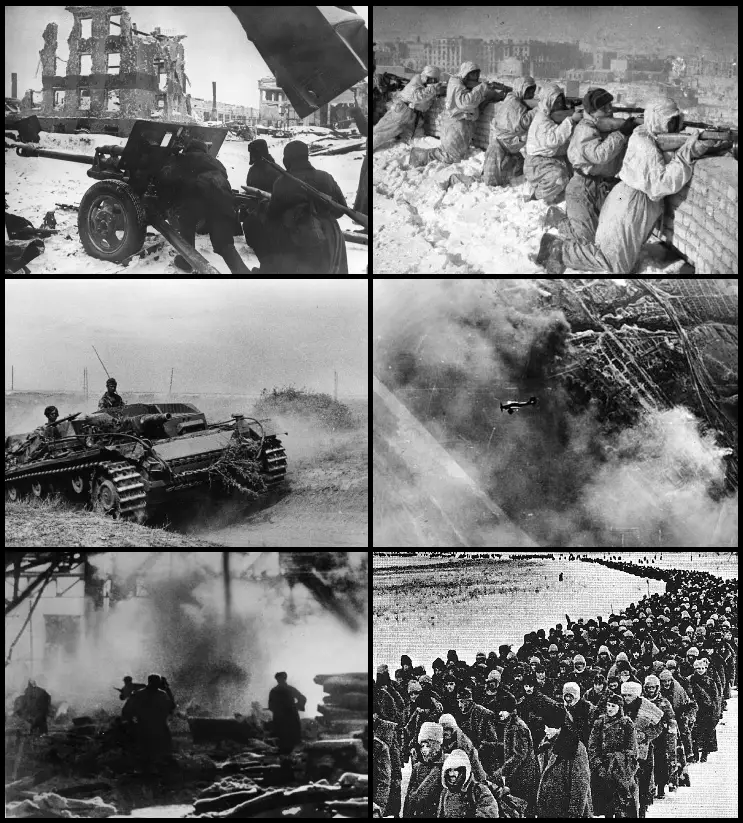

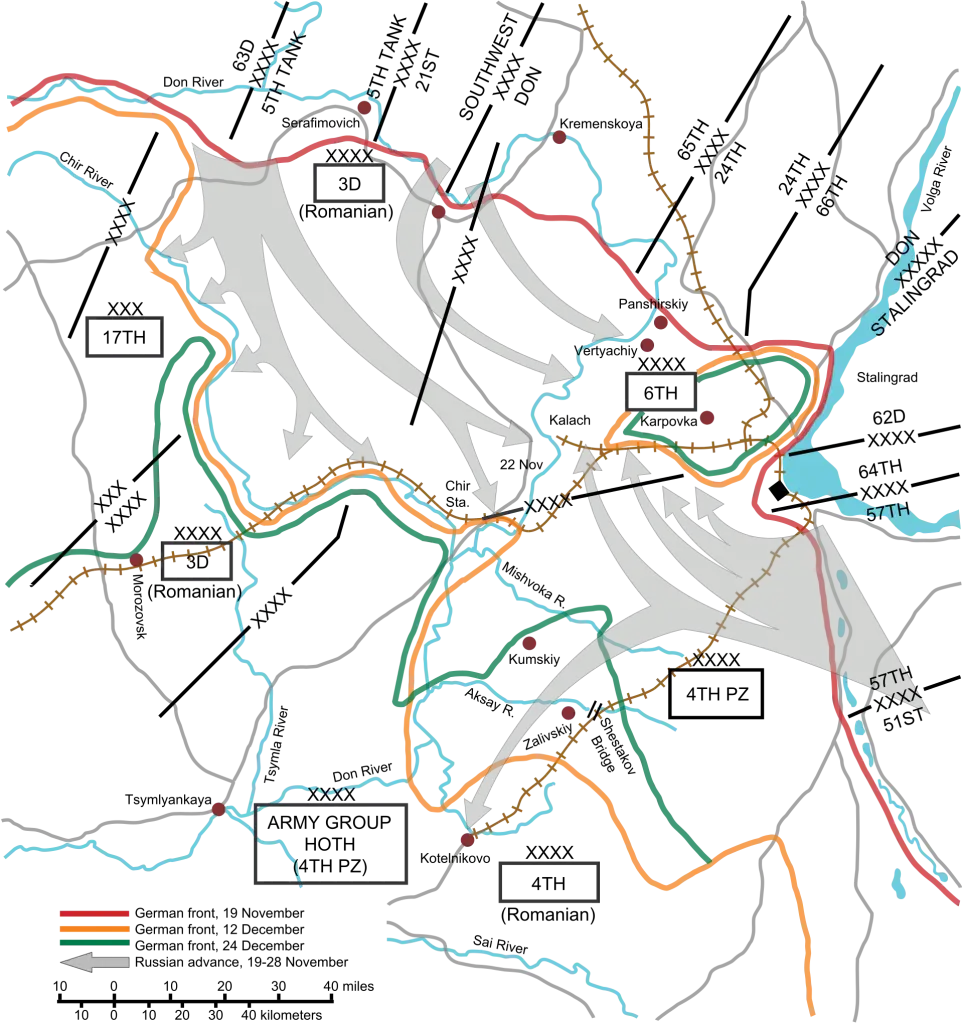

Battle of Stalingrad (1942-1943, Russia)

- What happened: One of the bloodiest battles in history, Stalingrad witnessed brutal urban warfare between German and Soviet forces. The German defeat marked a turning point on the Eastern Front, halting the German advance and shifting the momentum toward the Soviets.

- Key takeaway: Resilience, determination, and the ability to endure immense hardship can be decisive factors in warfare.

Sicilian Expedition (415-413 BC, Silicy)

(Wiki Image).

Ten notable quotes:

From Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War:

- “The Athenians, with a view to this expedition, had voted to send sixty ships to Sicily, under the command of Nicias, Alcibiades, and Lamachus.” – This sets the stage, introducing the key Athenian leaders and the initial scope of the expedition.

- “They were to assist the Egestaeans against the Selinuntines, and, if they had time, to regulate the affairs of Sicily in general.” – This reveals the initial, somewhat vague, objectives of the expedition.

- “Nicias was appointed to the command much against his will, for he was already advanced in years, and he thought himself unfit for service.” – This highlights Nicias’ reluctance and foreshadows potential leadership challenges.

- “Alcibiades, on the other hand, was eager to be at the head of the expedition, and hoped to reduce Sicily and Carthage, and after these successes to increase his private fortune and reputation.” – This reveals Alcibiades’ ambition and personal motives, which would later play a role in the expedition’s downfall.

- “The expedition’s departure was a sight that struck the beholders with awe. Never had a single city of Hellas sent forth such a fleet or such a magnificent armament.” – This captures the grandeur and scale of the Athenian expedition, highlighting the initial sense of confidence and power.

From other sources:

- “Our city, strong in its men and its ships, has sent me to you, to free your people from the oppression of the Syracusans.” (Alcibiades, addressing the Sicilian city of Catana) – This illustrates Alcibiades’ persuasive rhetoric and his attempt to gain allies in Sicily.

- “The Athenians, having come with a great fleet and army, have been defeated by the Syracusans and their allies and have lost all their ships. They have mostly perished, some by the sword and some by falling into the hands of the enemy.” (Plutarch, describing the final defeat) – This starkly conveys the magnitude of the Athenian disaster.

- “The Sicilian Expedition was the ruin of Athens.” (Diodorus Siculus) – This emphasizes the long-term impact of the defeat, contributing to the decline of Athenian power.

Reflecting on the disaster:

- “Pride goes before destruction, a haughty spirit before a fall.” (Proverbs 16:18) – This biblical proverb captures the theme of Athenian hubris and the consequences of overconfidence.

- “The greatest life lesson is to know that even fools are right sometimes.” (Winston Churchill) – While not directly related to the Sicilian Expedition, this quote highlights the importance of humility and the dangers of dismissing opposing viewpoints, a lesson the Athenians learned the hard way.

Casualties

| Force | Commander(s) | Ships (Start) | Men (estimated) | Casualties | Prisoners | Ships Lost |

| Athenian Expeditionary Force | Nicias, Alcibiades, Lamachus | 134 Triremes | ~50,000 (including rowers and support staff) | Very high, almost the entire force | Thousands captured by Syracuse | Almost all ships lost |

| Syracusan and Spartan Forces | Hermocrates, Gylippus | Initially fewer, later surpassing Athenian numbers | Initially, fewer later reinforced | Significant, but lower than Athenian losses | Some Athenians were captured, but many were killed | Significant losses, but fewer than Athenian losses |

The Sicilian Expedition: How One Campaign Decided Ancient …

The Sicilian Expedition – Complete Documentary

(YouTube video)

The Sicilian Expedition was a significant military campaign undertaken by the Athenian Empire during the Peloponnesian War against the city-state of Syracuse in 415-413 BC. This ambitious undertaking aimed to expand Athenian power in the western Mediterranean but ultimately resulted in one of the most catastrophic defeats in Athenian history. The expedition reflected the overreach of Athenian imperial ambitions and marked a turning point in the war against the Peloponnesian League, led by Sparta.

Background

The origins of the Sicilian Expedition can be traced to the broader context of the Peloponnesian War, which erupted in 431 BC between Athens and Sparta, along with their respective allies. By 415 BC, Athens had maintained a dominant position in the Aegean Sea but sought to further extend its influence by turning its attention to Sicily. The island, rich in resources and strategically located, was seen as an opportunity to bolster Athenian power and counteract Spartan influence in the region. Influenced by the orator Alcibiades, the Athenian assembly voted in favor of the expedition, leading to the mobilization of a substantial naval force.

The Objectives

The primary objective of the Sicilian Expedition was to conquer Syracuse, a powerful city-state that had the potential to challenge Athenian interests in Sicily and beyond. The Athenians aimed to gain control over Sicily’s rich agricultural land, secure trade routes, and use the island as a base for further military operations in the western Mediterranean. The expedition also hoped to encourage revolts among other Sicilian city-states against Syracuse, weakening its power and influence.

The Initial Stages

The route the Athenian fleet took to Sicily (Wiki Image).

In the spring of 415 BC, Athens launched the expedition, dispatching a formidable fleet comprising approximately 134 ships and an army of around 20,000 soldiers, including hoplites, light infantry, and cavalry. The campaign’s initial stages were marked by successes, with Athenian forces capturing several coastal cities and gaining local support. The Athenians laid siege to Syracuse, but the Syracusans, bolstered by their military resources and alliances, mounted a determined defense.

The Role of Leadership

Key figures in the expedition included the charismatic leader Alcibiades, who initially played a crucial role in rallying support for the campaign. However, political turmoil in Athens led to his abrupt departure from the expedition due to accusations of sacrilege. His departure marked a significant turning point, as leadership fell into the hands of less experienced commanders, leading to disorganization and a lack of strategic vision. The loss of Alcibiades and subsequent leadership changes significantly undermined the Athenian campaign.

The Turning Point

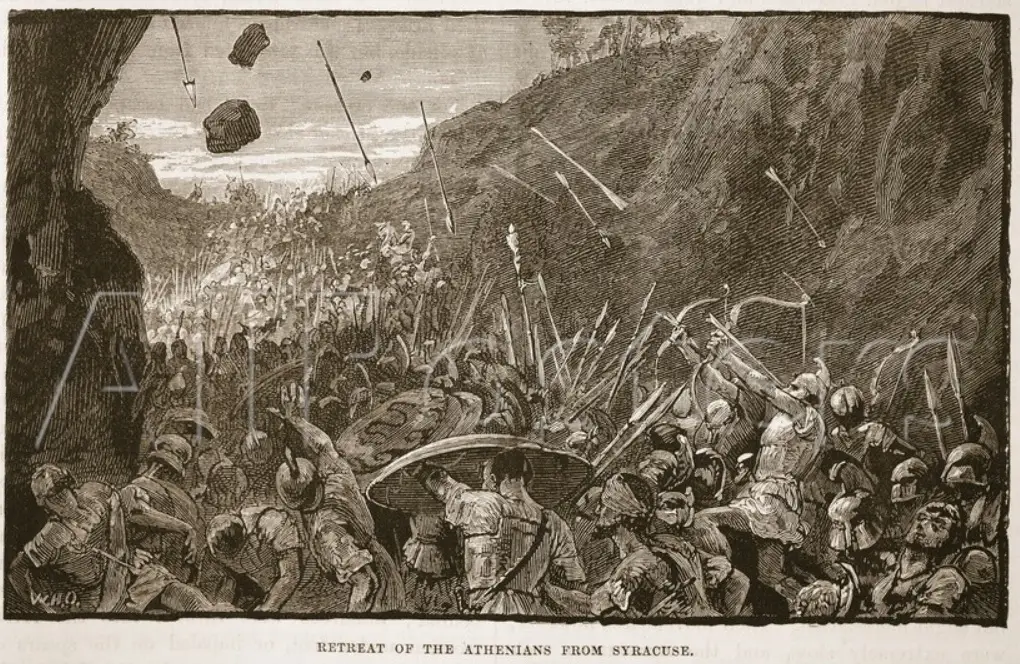

Map of the siege showing walls and counter-walls (Wiki Image).

The tide of the campaign began to turn against the Athenians in 413 BC when the Syracusans, reinforced by Spartan support and skilled military commanders, launched a counteroffensive. The Athenians found themselves increasingly isolated and besieged within their camps. Their supply lines were cut, and morale plummeted as defeat set in. The Battle of Syracuse, which included naval engagements and land battles, showcased the Athenian fleet’s vulnerabilities and the effectiveness of the Syracusan forces.

The Catastrophic Defeat

The Sicilian Expedition culminated in 413 BC when the Athenians faced a devastating defeat at Syracuse. The city’s defenses, bolstered by Spartan and local support, proved insurmountable for the exhausted Athenian forces. The Athenians suffered heavy casualties, with thousands killed or captured, including many soldiers and sailors who had been pivotal to the expedition. The remnants of the Athenian fleet were destroyed, effectively crippling Athens’ naval power in the region.

Aftermath and Consequences

The disastrous outcome of the Sicilian Expedition had far-reaching consequences for Athens and the course of the Peloponnesian War. Losing manpower, resources, and ships severely weakened Athenian military capabilities and morale. Additionally, the failure disillusioned many Athenians, leading to a shift in public opinion regarding imperial ambitions. The campaign’s failure also emboldened Athens’ enemies, notably Sparta, which capitalized on the Athenian defeat to gain an upper hand in the war.

Historical Significance

The Sicilian Expedition is a cautionary tale about the dangers of overextension and imperial ambitions’ hubris. It highlighted the vulnerabilities of even the most powerful states when faced with determined local resistance and effective leadership. The events in Sicily ultimately marked a turning point in the Peloponnesian War, setting the stage for Athens’ eventual defeat in 404 BC and the end of its imperial dominance. The expedition is often studied as a classic example of strategic failure and the consequences of miscalculation in military history.

Battle of Cannae (216 BC, Italy)

Hannibal counted the Roman knights’ signet rings killed during the battle, statue by Sébastien Slodtz, 1704, Louvre (Wiki Image).

Ten notable quotes:

Here are ten famous quotes relating to the Battle of Cannae (216 BC), one of the most significant military confrontations during the Second Punic War between Rome and Carthage:

- Hannibal Barca: “Let us see whether fear of defeat can make the Romans bolder than the hope of victory.”

– Hannibal’s bold confidence before the battle. - Livy: “There never was a greater slaughter of Romans than this.”

– Livy, a Roman historian, summarizes the magnitude of Roman losses. - Polybius: “The surrounding plain was full of dead bodies, and the adjacent rivers were discolored with blood.”

– A vivid account from the ancient historian Polybius. - Livy: “The greater the defeat, the more dangerous the enemy they faced afterward.”

– Livy commenting on the consequences of Roman defeat. - Hannibal: “The Romans, more than ever, dread Carthage’s armies after this victory.”

– Hannibal reflecting on the psychological impact of his victory. - Polybius: “Never were so many killed in one battle; for of seventy thousand Roman soldiers, not three thousand escaped.”

– Polybius describes the scope of the Roman casualties. - Quintus Fabius Maximus: “It is the strategy, not the sword, that wins wars.”

– Fabius Maximus, a Roman commander who advocated avoiding direct conflict with Hannibal, which was ignored at Cannae. - Appian: “They say the Romans despaired of the war when they heard of the result of the Battle of Cannae.”

– Appian comments on the despair Romans felt following the catastrophic loss. - Cicero: “At Cannae, we lost not only our men but our honor.”

– Cicero’s reflection on the symbolic defeat suffered by Rome. - Hannibal: “Victory is not the outcome of strength alone but strategy and timing.”

– Hannibal’s philosophy on warfare is reflected in his masterful tactics at Cannae.

Casualties

| Forces | Number of Troops | Casualties (Killed) | Prisoners | Wounded |

| Roman Army | ~86,000 | ~50,000–70,000 | ~10,000–15,000 | Unknown |

| Carthaginian Army (Hannibal) | ~50,000 | ~5,700 | Minimal (if any) | Unknown |

Rome’s Bloodiest Battle | The Day Rome Nearly Fell! | Cannae …

The Battle of Cannae (216 B.C.E.)

Rome Vs Carthage: Battle of Cannae 216 BC | Cinematic

(YouTube video)

The Battle of Cannae, fought in 216 BC during the Second Punic War, is one of history’s most significant military engagements. It was a pivotal moment in the conflict between the Roman Republic and Carthage, led by the brilliant general Hannibal Barca. The battle is particularly noted for Hannibal’s tactical genius, which resulted in a devastating defeat for the Romans and had long-lasting implications for the war and Roman military strategy.

Historical Context

The Second Punic War erupted in 218 BC after Hannibal’s daring crossing of the Alps into Italy, following a series of events that stemmed from the First Punic War. By 216 BC, Hannibal had already achieved significant victories against Roman forces, including the Battle of Lake Trasimene. The Romans, intent on avenging their losses and regaining control, mobilized a large army to confront Hannibal. This set the stage for the confrontation at Cannae, a strategic location in southeastern Italy.

The Roman Army

The Roman forces at Cannae were formidable, consisting of an estimated 86,000 soldiers, including legions and auxiliary units. Under the command of Lucius Emilius Paullus and Gaius Terentius Varro, the Romans aimed to encircle and annihilate Hannibal’s much smaller army. Confident in their numbers, the Romans sought to engage Hannibal in a decisive battle, believing a victory would end his threat to Rome and restore Roman pride after previous defeats.

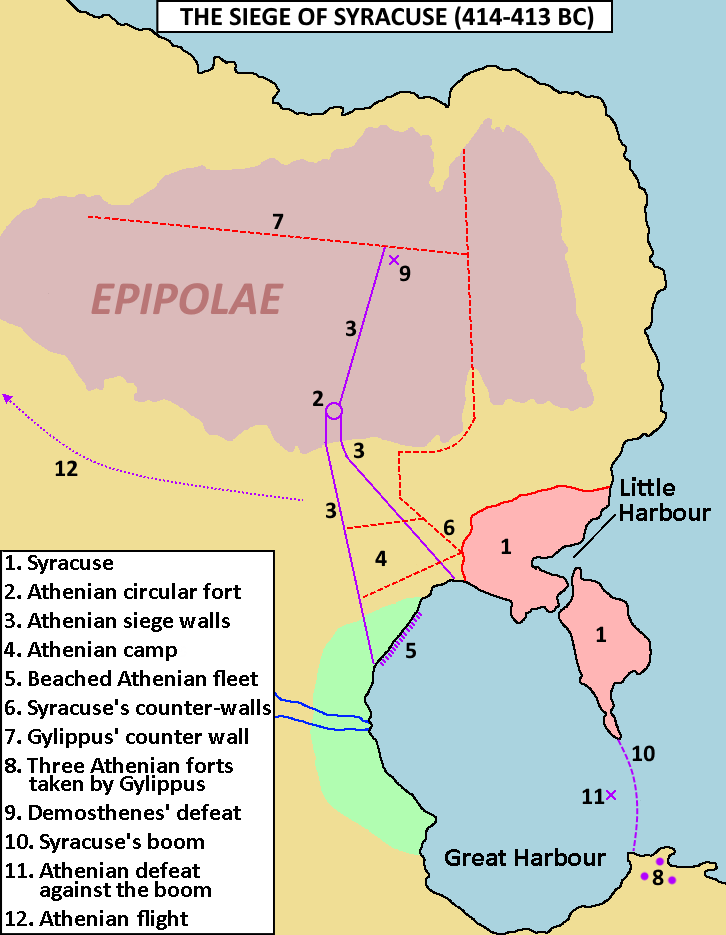

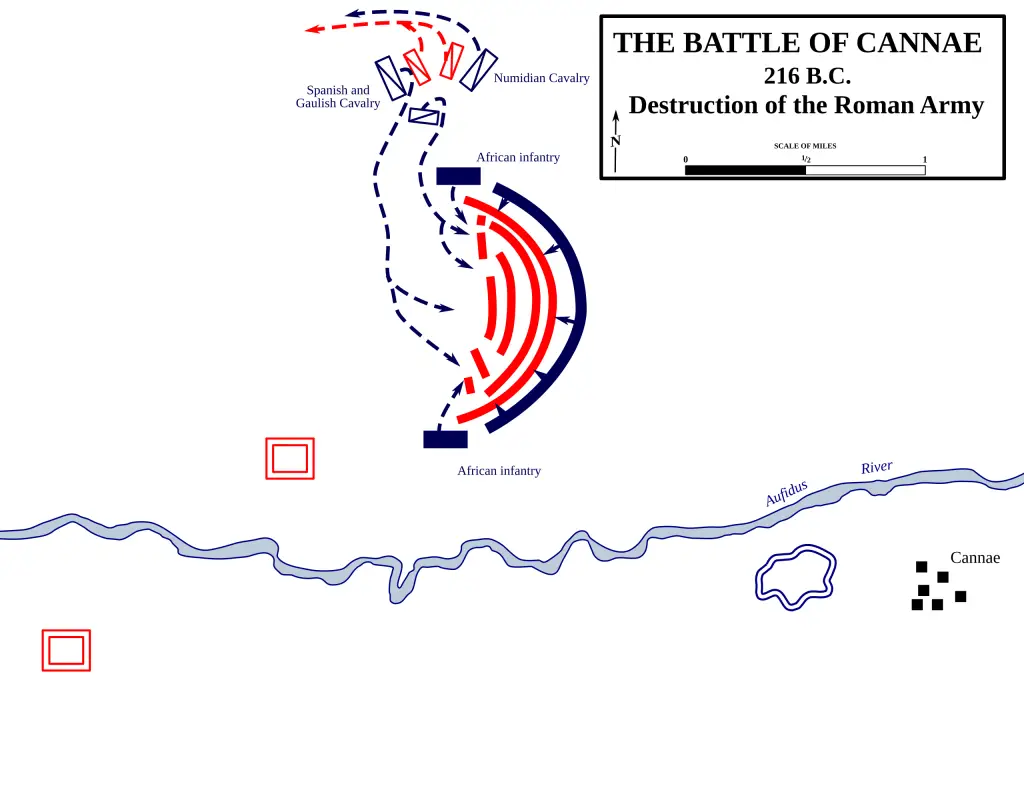

Hannibal’s Strategy

The initial deployment and Roman attack (in red) (Wiki Image).

Hannibal, commanding approximately 50,000 troops, employed a brilliant tactical strategy that would become a hallmark of military instruction for centuries. His army was composed of a diverse mix of Carthaginian soldiers, Numidian cavalry, and Gallic warriors. Understanding the strengths and weaknesses of his forces and the Romans, Hannibal devised a plan that leveraged his troops’ mobility and combat experience. He positioned his army in a crescent formation, inviting the Romans to attack.

The Battle Unfolds

On the day of the battle, Hannibal’s forces engaged the Romans, initially allowing them to advance. As the Romans pressed their attack, they became increasingly overextended, falling into the trap that Hannibal had set. Once the Romans were committed to the assault, Hannibal ordered his cavalry, commanded by Hasdrubal, to engage the Roman flanks. The Carthaginian infantry then pivoted inward, encircling the Roman forces, effectively trapping them in a deadly pincer movement.

The Decisive Moment

The destruction of the Roman army (Wiki Image).

The combat at Cannae was intense and brutal, with the Romans fighting fiercely to break the encirclement. However, Hannibal’s tactical brilliance and the discipline of his troops proved overwhelming. The Romans, lacking space to maneuver and being attacked from all sides, suffered catastrophic losses. Estimates suggest that around 50,000 to 70,000 Roman soldiers were killed, while many others were captured. This defeat not only decimated the Roman army but also shattered their morale.

Aftermath and Consequences

The aftermath of the Battle of Cannae was profound, with the Carthaginian victory sending shockwaves through Rome and the entire Mediterranean. The Romans were left to grapple with losing a significant portion of their army and the potential for further Carthaginian advances into Italy. Despite the defeat, Rome did not capitulate; instead, they adopted a strategy of attrition, focusing on avoiding large-scale confrontations with Hannibal’s forces while seeking to wear them down over time.

The Legacy of Cannae

Cannae has been studied extensively throughout military history and is often cited as a classic example of the double envelopment tactic. Hannibal’s victory inspired military leaders, and generations of commanders have analyzed the battle’s lessons in strategy and tactics. It also shaped Roman military doctrine, prompting reforms that would eventually lead to Rome’s resurgence and the eventual defeat of Carthage in the Second Punic War.

Conclusion

The Battle of Cannae remains a pivotal event in military history, illustrating the potential for tactical genius to overcome numerical superiority. Hannibal’s victory not only altered the Second Punic War but also left an indelible mark on the principles of warfare. The lessons learned from Cannae resonate in military strategy, serving as a testament to the enduring impact of one of history’s greatest battles.

Teutoburg Forest (9 AD, Germany)

Martin Disteli‘s 1830s lithograph of Varus falling on his sword during the Battle of Teutoburg Forest (Wiki Image).

Cenotaph of Marcus Caelius, 1st centurion of XVIII, who “fell in the war of Varus” (‘bello Variano’) (Wiki Image).

Ten notable quotes:

Here are ten famous quotes related to the Battle of Teutoburg Forest (9 AD), one of the most catastrophic defeats for the Roman Empire at the hands of Germanic tribes led by Arminius:

- Emperor Augustus: “Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!”

– Augustus’s anguished cry upon hearing of the disaster expresses the depth of the loss. - Tacitus: “The soldiers’ bones were still lying unburied in the forest after all these years, scattered where they had fallen.”

– Roman historian Tacitus on the battlefield remains years later. - Velleius Paterculus: “Never was there a disaster more bloody, more shocking than this.”

– Roman historian Velleius describes the sheer magnitude of the Roman defeat. - Arminius: “It is not by power alone that the Romans are overcome but by the subtlety of strategy.”

– Arminius reflecting on the clever tactics he used to defeat the Romans. - Cassius Dio: “All were slaughtered… in the forest, in the swamps, in the ravines; no one survived.”

– Cassius Dio emphasizes the total destruction of the Roman forces. - Tacitus: “He [Arminius] was the liberator of Germany.”

– Tacitus credits Arminius with the unification and liberation of Germanic tribes against Roman domination. - Publius Quinctilius Varus (alleged last words): “We are undone.”

– Varus, the Roman general in command, realized the gravity of the defeat before his death. - Tacitus: “That day changed the destinies of empires.”

– Tacitus summarizes the long-term impact of the battle on both Rome and Germany. - Suetonius: “Three whole legions were destroyed; hardly a man escaped to bring the news.”

– Suetonius outlining the catastrophic losses suffered by Rome. - Arminius: “Freedom is the greatest reward for the fight.”

– Arminius speaking about the motivation of the Germanic tribes in their revolt against Roman rule.

Casualties

| Force | Commander | Men (estimated) | Killed | Wounded | Prisoners | Total Casualties (estimated) |

| Roman Legions | Publius Quinctilius Varus | 17,000 – 20,000 | 15,000 – 20,000 | Few | Several thousand | 15,000 – 20,000+ |

| Germanic Tribes | Arminius | 10,000 – 20,000 | Unknown | Unknown | Few | Unknown |

The Battle of Teutoburg Forest 9 AD: When Trees Start …

Roman Empire Vs Germanic Tribes: Battle of Teutoburg forest …

Teutoburg Forest 9 AD – Roman-Germanic Wars …

(YouTube video)

The Battle of Teutoburg Forest, fought in 9 AD, marks one of the most significant defeats in Roman military history. It resulted in annihilating three Roman legions under Publius Quinctilius Varus’s command. This battle not only halted the expansion of the Roman Empire into Germany but also had profound repercussions for Rome’s political and military strategies. The events surrounding this conflict reflect the complexities of Roman-Germanic relations and the fierce resistance of the Germanic tribes against Roman dominance.

Historical Context

By the late 1st century BC, Rome had significantly expanded its territory and influence across Europe. Under Augustus’s leadership, the Roman Empire sought to consolidate its power and expand into Germany. Various tribes populated the region, collectively referred to as the Germanic peoples, who were known for their fierce warrior culture and resistance to foreign domination. Varus, appointed governor of the newly annexed provinces, aimed to bring Roman civilization to the tribes, but this approach was met with resentment and hostility.

The Setup for Conflict

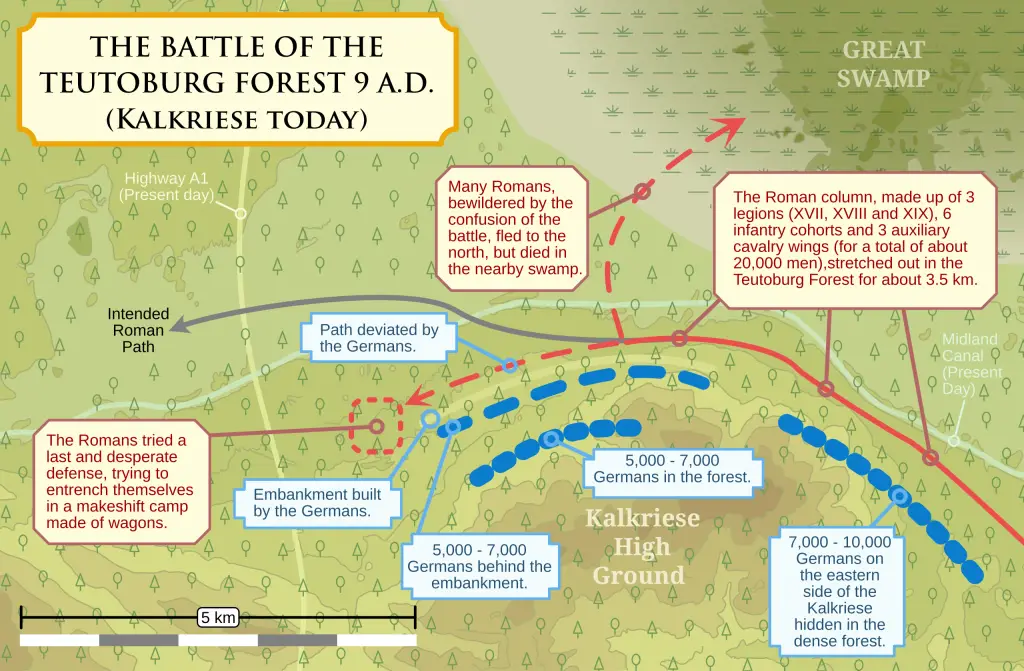

In the years leading up to the battle, Varus sought to impose Roman law and customs on the Germanic tribes, which fueled tensions. His administration included heavy taxation and the introduction of a Roman military presence in the region. The Germanic chieftain Arminius, a former auxiliary officer in the Roman army who had gained Varus’s trust, played a crucial role in the unfolding conflict. Disguised as a loyal ally, Arminius began to unify the Germanic tribes, including the Cherusci, Chatti, and others, against the Roman threat.

The Betrayal

Arminius’s plan culminated in the summer of 9 AD when he deceived Varus into believing that a minor uprising was occurring in the region. This led Varus to march his legions—comprising the Legions XVII, XVIII, and XIX—deep into the Teutoburg Forest. Confident in his superior military strength, Varus fell into Arminius’s trap. The Germanic tribes had strategically planned an ambush, exploiting their intimate knowledge of the dense forest terrain unfamiliar to the Roman soldiers.

The Ambush

Map showing the defeat of Publius Quinctilius Varus at Kalkriese (Wiki Image).

As the Roman legions advanced through the Teutoburg Forest, Arminius and his confederation of tribes unexpectedly attacked them from all sides. The dense underbrush and narrow pathways hindered the Roman formations’ maneuverability. The Germanic warriors used hit-and-run tactics, launching surprise attacks and retreating into the trees. The Romans, accustomed to open-field combat, found themselves disoriented and vulnerable in the unfamiliar environment.

The Decimation of the Legions

The battle raged for several days, with the Roman legions suffering devastating losses. Realizing the dire situation, Varus attempted to retreat, but the Germanic forces pursued relentlessly. The Romans, who had initially numbered around 20,000, were systematically picked off, with only a fraction managing to escape. The culmination of this catastrophic defeat resulted in the near-total destruction of Varus’s legions, marking a turning point in Rome’s ambitions in Germany.

Aftermath and Consequences

The defeat at Teutoburg Forest had profound implications for the Roman Empire. News of the disaster spread rapidly, causing panic in Rome and leading to a reassessment of imperial policies regarding Germany. After losing, Augustus lamented, “Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!” The Roman Empire effectively abandoned its ambitions to expand further into Germany, establishing a more defensive stance along the Rhine River, which would become the new frontier.

The Legacy of the Battle

Teutoburg Forest became a symbol of Germanic resistance and national pride. The battle significantly shaped the identity of the Germanic tribes, fostering a sense of unity against external threats. For centuries, the event was memorialized in folklore, literature, and later historical accounts, such as those by the Roman historian Tacitus. The battle’s legacy inspired future generations in their struggles against foreign domination.

Conclusion

The Battle of Teutoburg Forest represents a critical juncture in the history of Rome and Germany, highlighting the complexities of imperial expansion and the fierce determination of indigenous peoples to resist colonization. The defeat had lasting ramifications for the Roman Empire, influencing military strategy and policy in the region for years. The battle remains a testament to the resilience of the Germanic tribes and their ability to unite against a formidable adversary, ultimately altering the course of European history.

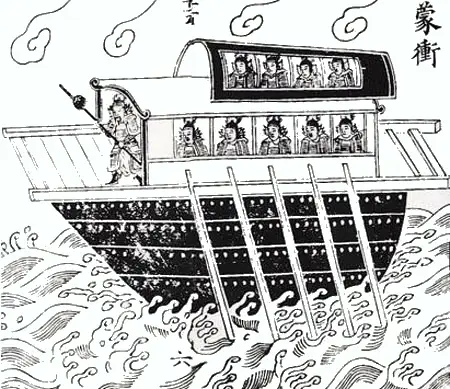

Battle of Red Cliffs (208 AD, China)

Engravings on a cliff-side near a widely accepted candidate site for the battlefield, in the vicinity of Chibi, Hubei. The engravings are at least 1000 years old and include the Chinese characters 赤壁 (‘red cliffs’) written from right to left (Wiki Image).

A depiction of a mengchong, an assault warship used in the battle that was covered in leather and designed to break enemy lines – the Wujing Zongyao, c. 1040 (Wiki Image).

Ten notable quotes:

Here are ten famous quotes related to the Battle of Red Cliffs (208 AD), one of the most significant battles in Chinese history during the late Han Dynasty, where the forces of Sun Quan and Liu Bei defeated Cao Cao’s massive army:

- Cao Cao: “I have a million soldiers, and they have nothing but rivers and mountains to protect them. How could they possibly resist me?” – Cao Cao’s overconfidence before the battle, believing his superior numbers would guarantee victory.

- Zhuge Liang: “The strength of the south lies in our waterways. We will use fire to break Cao Cao’s fleet and his will.” – Zhuge Liang, Liu Bei’s brilliant strategist, explaining his plan to take advantage of the environment.

- Sun Quan: “Even if the mountains and rivers burn, we will defend our land.” Sun Quan, the leader of the southern forces, expressed his determination to resist Cao Cao’s invasion.

- Zhou Yu: “A true general must understand both heaven’s timing and the enemy’s weaknesses.” – Zhou Yu, Sun Quan’s commander, reflecting on the importance of strategy and timing in warfare.

- Cao Cao: “The wind, the fire, everything is against me. Heaven has forsaken me!” – Cao Cao’s realization during the battle, as his fleet is set ablaze by fire ships.

- Zhuge Liang: “Cao Cao’s army is like a dragon that has crossed a river, majestic but out of its element.” – Zhuge Liang metaphorically describes Cao Cao’s army as strong but vulnerable in unfamiliar terrain.

- Sima Yi: “Victory is not always in the hands of the greater force.” – Sima Yi, Cao Cao’s advisor, acknowledging that numbers alone do not guarantee victory in warfare.

- Zhou Yu: “Strike when the wind is right, and the flames will devour his ships.” – Zhou Yu’s crucial command to launch the fire attack timed perfectly with the eastern wind.

- Sun Quan: “The unity of our people and the might of our land will never be broken by force.” – Sun Quan rallied his troops to defend the southern states and maintain their independence.

- Zhuge Liang: “This is not the end of our fight; it is merely the beginning of the great divide.” – Zhuge Liang predicted that the victory at Red Cliffs would mark the beginning of the division of China into three kingdoms.

Casualties

| Force | Commander(s) | Ships (estimated) | Men (estimated) | Killed/Wounded | Prisoners | Ships Lost/Captured |

| Cao Cao’s Forces | Cao Cao | 800+ | 220,000 – 800,000 | Heavy | Many | Majority |

| Sun Quan’s Forces | Zhou Yu, Lu Su | 300+ | 50,000 | Moderate | Some | Few |

| Liu Bei’s Forces | Liu Bei, Zhuge Liang | 100+ | 20,000 | Light | Some | Few |

Export to Sheets

The Battle of Red Cliffs |AD 208|(Battle of Chibi) Total War …

The Battle of Red Cliffs

Red Cliffs and Jiangling 208 – THREE KINGDOMS …

(YouTube video)

The Battle of Red Cliffs, fought in the winter of 208 AD, is a pivotal conflict in ancient Chinese history, marking a crucial turning point during the late Eastern Han dynasty. This battle was primarily between the forces of the warlord Cao Cao and the allied forces of Sun Quan and Liu Bei. The confrontation not only showcased strategic military maneuvers but also set the stage for the eventual division of China into the Three Kingdoms, influencing the political landscape for centuries.

Historical Context

In the late 2nd century AD, the Han dynasty was in decline, plagued by corruption and power struggles. Amid this chaos, regional warlords emerged, vying for control over China. Cao Cao, a powerful warlord and the de facto ruler of northern China sought to expand his influence by conquering southern territories. His ambition to unite the country under his rule set the stage for the conflict at Red Cliffs, as the southern warlords, Sun Quan and Liu Bei, allied to resist his advances.

The Lead-Up to Battle

By 208 AD, Cao Cao had successfully conquered the northern territories and marched south with an army of over 200,000. His forces were well-equipped and organized, posing a significant threat to the southern warlords. In response, Sun Quan and Liu Bei, recognizing the danger posed by Cao Cao, allied together despite their previous conflicts. The two leaders strategically positioned their forces along the Yangtze River, specifically near the Red Cliffs, where they planned to use the terrain to their advantage.

Strategic Advantages

The geography of the battlefield played a crucial role in the outcome of the Battle of Red Cliffs. The Yangtze River was a natural barrier against Cao Cao’s larger army. Furthermore, Sun Quan’s forces, predominantly composed of skilled archers and naval troops, were better suited for combat on the water. Liu Bei’s men, although fewer in number, were motivated to defend their homeland. This combination of terrain and morale would prove critical in the upcoming conflict.

The Battle Begins

Battle of Red Cliffs and Cao Cao’s retreat (Wiki Image).

The battle commenced with skirmishes along the river as both sides sought to gain the upper hand. Cao Cao attempted to exploit his numerical advantage by launching frontal assaults. However, the southern forces skillfully utilized their river knowledge and naval capabilities, effectively repelling the attacks. The tides turned when Zhou Yu, a prominent general serving under Sun Quan, devised a plan to use fire as a weapon against Cao Cao’s fleet.

The Inferno Strategy

Zhou Yu’s plan involved launching a surprise fire attack against Cao Cao’s ships, which were tightly clustered together for logistical efficiency. Under the cover of night, the southern forces set fire to a fleet of ships loaded with dry timber and flammable materials. The flames quickly spread, engulfing many of Cao Cao’s vessels and causing chaos among his troops. This tactic decimated Cao Cao’s naval strength and demoralized his army, contributing to a rapid decline in their fighting spirit.

Aftermath of the Battle

The defeat at the Battle of Red Cliffs was catastrophic for Cao Cao. With his forces significantly weakened and morale shattered, he retreated to northern China. Sun Quan and Liu Bei’s victory solidified their alliance and began a new power dynamic in China. The battle became a legendary tale of strategy and heroism, encapsulated in the historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, dramatizing the events and personalities involved.

Political Ramifications

In the aftermath of the battle, the power dynamics in China shifted dramatically. Sun Quan emerged as the ruler of the southern territories, establishing the Eastern Wu state, while Liu Bei gained legitimacy and support, ultimately founding the Shu Han state. The battle set the stage for the Three Kingdoms Period, a time characterized by continuous warfare, shifting alliances, and the rise of legendary figures such as Zhuge Liang, Sun Quan, and Liu Bei.

Conclusion

The Battle of Red Cliffs is a significant event in Chinese history for its immediate military outcomes and its long-lasting impact on the political landscape. The alliance between Sun Quan and Liu Bei, forged in the crucible of battle, would shape the trajectory of the Three Kingdoms era. The strategies employed, particularly the innovative use of fire, have been studied and admired for their ingenuity. Ultimately, the Battle of Red Cliffs remains a testament to the complexities of war and the enduring struggle for power in ancient China.

“Kamikaze” or Divine Wind (1274 & 1281, Japan)

The Mongol fleet was destroyed in a typhoon, ink and water on paper, by Kikuchi Yōsai in 1847 (Wiki Image).

Two Samurai with a dead Mongol at their feet. The one on the right is possibly Sō Sukekuni, the defending commander at Tsushima—votive image (ema) at the Komodahama Shrine at Sasuura on Tsushima (Wiki Image).

Ten notable quotes:

Here are ten quotes related to the “Kamikaze” or “Divine Wind” during the Mongol invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281:

- “The wrath of the gods swept through the invaders, scattering their mighty fleet like leaves before a storm.” – Traditional Japanese proverb.

- “The divine wind came to our rescue when our swords could not.” – Anonymous samurai warrior reflecting on the Mongol invasions.

- “The winds that saved us were the very breath of the kami, sent from the heavens to protect our sacred land.” – Japanese priest in the storm’s aftermath.

- “The destruction of our ships was not by the hand of men, but by the fury of nature herself.” – Mongol survivor of the failed invasions.

- “The gods have intervened on behalf of their people, ensuring that the land of the rising sun remains untouched by foreign hands.” – Contemporary Japanese historian.

- “In the face of overwhelming force, we prayed for deliverance, and the sea answered our call.” – Samurai account from the invasion of 1274.

- “Our horses would not charge into the heart of the storm; it was as though they could sense the coming tempest.” – Mongol officer before the storm of 1281.

- “The heavens themselves guarded Japan, sending not one, but two tempests to destroy the enemy’s ambitions.” – Scholar describing the two typhoons.

- “For a nation without walls, it was the walls of the storm that protected us.” – Samurai leader after the 1281 invasion attempt.

- “It was not skill or valor that defeated the Mongols, but the will of the wind and the favor of the gods.” – Later Japanese chronicler reflecting on the invasions.

Casualties

| Force | Commander | Ships (Start) | Men (estimated) | Killed/Drowned | Prisoners | Ships Lost |

| 1st Mongol Invasion (1274) | Kublai Khan | 500-900 | 30,000-40,000 | 13,000+ | Unknown | Most |

| 2nd Mongol Invasion (1281) | Kublai Khan | 4,400 | 140,000 | 70,000+ | Unknown | Most |

| Japanese Forces (both invasions) | Hōjō Tokimune | Varies | 40,000 (1281) | Relatively few | Some | Few |

Mongol Invasions of Japan 1274 and 1281 – Full History

Mongol vs Japan: How Khan Army Was Defeated in Japan …

Mongol Invasion of Japan (1281)

(YouTube video)

The term “Kamikaze,” or “Divine Wind,” refers to a series of typhoons that played a pivotal role in two attempted invasions of Japan by Mongol forces in the late 13th century, specifically in 1274 and 1281. These extraordinary storms, which devastated the invading fleets, have become emblematic of divine protection in Japanese culture and a symbol of resistance against overwhelming odds. The events surrounding the kamikaze have left a lasting legacy in Japanese history and mythology.

Historical Context

In the 13th century, the Mongol Empire, under the leadership of Kublai Khan, sought to expand its influence and power across East Asia. Following successful conquests in China and Korea, Kublai Khan turned his attention to Japan, viewing it as a strategic territory for further expansion. In 1274, the Mongol Empire launched its first invasion of Japan, utilizing a fleet composed of ships from various regions, including Korea and China. This initial invasion aimed to subjugate Japan and integrate it into the Mongol Empire.

The First Invasion (1274)

Mongol invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281 (Wiki Image).

The first invasion of Japan began in November 1274 when approximately 900 ships carrying around 15,000 soldiers arrived at the island of Tsushima. The Japanese defenders, significantly outnumbered, were initially overwhelmed. However, the samurai forces, known for their fighting prowess and determination, rallied and mounted a counterattack against the invaders. After fierce battles, the Mongols could not secure a decisive victory and retreated. Shortly after their withdrawal, a powerful typhoon struck the region, causing catastrophic damage to the Mongol fleet and drowning thousands of soldiers.

The Second Invasion (1281)

Undeterred by the failure of the first invasion, Kublai Khan ordered a second, larger invasion in 1281. This time, the Mongols assembled a massive armada of 4,000 ships and as many as 140,000 troops. This invasion involved two main fleets, one from Korea and another from southern China. As the Mongol forces approached Japan, they again faced resistance from the samurai, who were better prepared following the lessons learned from the previous invasion.

The Divine Wind Strikes Again

As the Mongol fleet gathered off the coast of Kamakura, the Japanese defenders prepared for battle. The two fleets launched an attack on August 15, 1281, but another formidable typhoon soon thwarted their efforts. This storm, which would later be dubbed the second kamikaze, wreaked havoc on the invading fleet, capsizing ships and drowning soldiers. It is estimated that around 100,000 Mongol troops perished in the storm, further ensuring Japan’s safety from foreign invasion.

Cultural Significance

The kamikaze concept transcends mere historical events; it has entered the realm of Japanese folklore and spirituality. The typhoons were interpreted as manifestations of divine intervention, protecting Japan from foreign invasion. As a result, the kamikaze became a symbol of national identity and resilience against overwhelming odds. The samurai’s bravery and the storms’ unexpected role in defending Japan are celebrated in literature, art, and religious practices, emphasizing that Japan was under the gods’ protection.

Political Ramifications

The failure of the Mongol invasions had significant political implications for Japan. Following the invasions, the Kamakura shogunate, which ruled Japan then, solidified its power and authority. The victories over the Mongols fostered a sense of national pride and unity among the Japanese. The shogunate used the successful defense against foreign invaders to strengthen its position and to rally support among the samurai class.

Lasting Legacy

The legacy of the kamikaze is evident in various aspects of Japanese culture and history. The events of 1274 and 1281 are commemorated in numerous monuments, festivals, and literary works. The term “kamikaze” itself resurfaced during World War II, when it was used to describe the suicide pilots of the Imperial Japanese Navy, drawing on the historical significance of the divine winds that had once protected Japan.

Conclusion

In summary, the “Kamikaze” of 1274 and 1281 represents a unique intersection of natural forces and human history, illustrating the impact of environmental conditions on military conflicts. These events thwarted foreign invasions and became integral to Japan’s national identity and cultural heritage. The kamikaze stands as a testament to the resilience of the Japanese spirit and the belief in divine protection, shaping the narrative of Japan’s history for centuries to come.

Battle of Agincourt (1415, France)

1915 depiction of Henry V at the Battle of Agincourt: The King wears on this surcoat the Royal Arms of England, quartered with the Fleur de Lys of France as a symbol of his claim to the throne of France (Wiki Image).

Miniature from Vigiles du roi Charles VII. The battle of Azincourt 1415 (Wiki Image).

Ten notable quotes:

Here are ten notable quotes related to the Battle of Agincourt (1415, France):

- “We few, we happy few, we band of brothers; For he to-day that sheds his blood with me shall be my brother.”

– William Shakespeare, Henry V, Act 4, Scene 3. - “All things are ready, if our minds be so.”

– William Shakespeare, Henry V, highlighting King Henry’s confidence before the battle. - “I would not lose so great an honor as one man more, methinks, would share from me, for the best hope I have.”

– William Shakespeare, Henry V, showing Henry’s defiance in the face of overwhelming odds. - “O God, Thy arm was here.”

– William Shakespeare, Henry V, Act 4, Scene 8, after the victory. - “Then call we this the field of Agincourt, fought on the day of Crispin Crispianus.”

– William Shakespeare, Henry V, marking the victory date. - “The English are so few that if we take them alive, there will be enough to lead them tied in strings.”

– French noble before the battle, underestimating the English. - “On that day, the English did not want prisoners; they slew all who fell into their hands.”

– Jean Froissart, French chronicler, on the brutality of the battle. - “Never was a victory so complete, or gained with so little loss, and yet so decisive in its results.”

– Sir John Fortescue, reflecting on Agincourt’s importance. - “Henry’s men fought as though each of them were worth three Frenchmen.”

– Contemporary chronicler on the incredible performance of the English troops. - “The flower of French nobility perished on the field of Agincourt.”

– Philippe de Mézières, describing the catastrophic loss for the French aristocracy.

Casualties

| Force | Commander | Men (estimated) | Killed | Wounded | Prisoners | Total Casualties (estimated) |

| English Army | King Henry V | 6,000 – 9,000 | 100-400 | ~1,000 | Few | 1,100 – 1,400 |

| French Army | Charles d’Albret | 12,000 – 36,000 | 6,000 – 10,000 | Unknown | ~1,500 | 7,500 – 11,500+ |

Export to Sheets

Battle of Agincourt, 1415 (ALL PARTS) ⚔️ England vs France …

The Battle of Agincourt Brought to Life in Stunning Animation …

Battle of Agincourt 1415 – Hundred Years’ War DOCUMENTARY

(YouTube video)

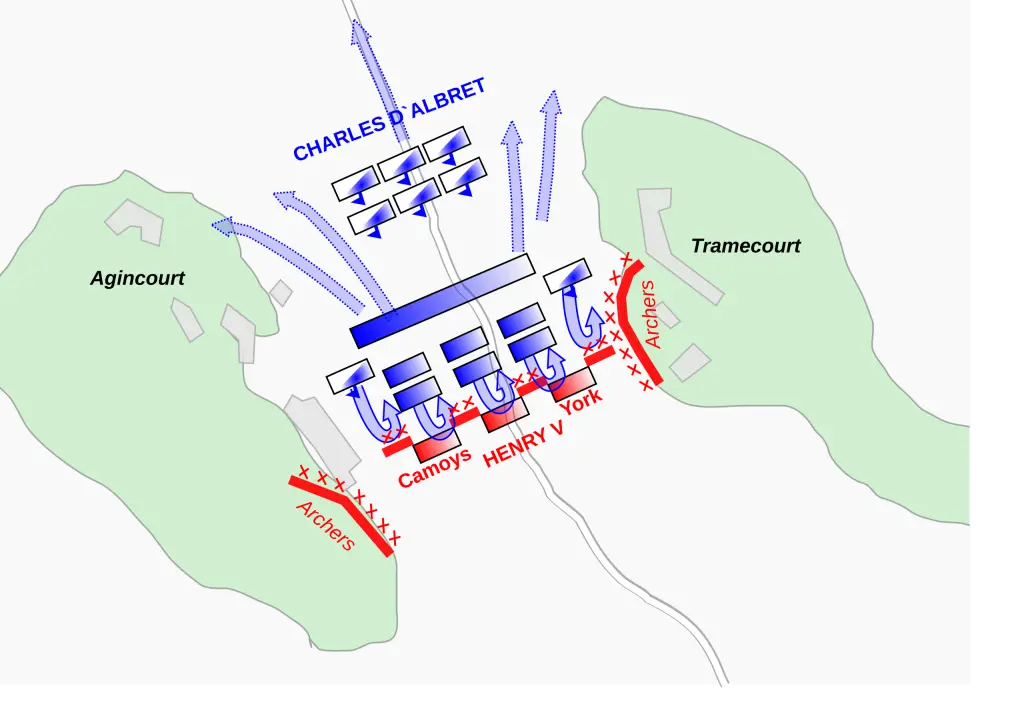

The Battle of Agincourt, fought on October 25, 1415, during the Hundred Years’ War, is one of English history’s most celebrated military engagements. This conflict saw the English army, led by King Henry V, achieve a stunning victory against the much larger French forces. The battle is notable for its tactical brilliance and enduring legacy in English culture, literature, and national identity.

Context and Prelude to the Battle

By the early 15th century, the Hundred Years’ War had raged for several decades, marked by conflicts between England and France over territorial claims and the right to the French crown. In 1415, King Henry V sought to reclaim English territories in France and assert his claim to the throne. Following a successful siege at Harfleur, Henry’s forces were weakened by disease and fatigue, prompting a retreat toward Calais. However, the French, eager to capitalize on their numerical superiority, gathered an army to intercept the English.

Forces and Preparations

The English army at Agincourt was significantly outnumbered, with estimates suggesting that Henry had around 6,000 to 9,000 men, while the French army could have numbered 20,000 to 40,000 soldiers. Despite these odds, the English forces were primarily composed of skilled longbowmen, whose ranged weaponry played a crucial role in the upcoming battle. The terrain at Agincourt was narrow and muddy, favoring the English strategy of using their longbows to devastating effect. Henry V prepared his men with a mix of discipline and morale, invoking a sense of unity and purpose.

The Battle Begins

The Battle of Agincourt (Wiki Image).

On the morning of October 25, the battle commenced in the muddy fields of Agincourt. The French forces advanced in heavily armored formations, relying on their cavalry and infantry to crush the English lines. However, the English longbowmen, positioned strategically along the flanks, unleashed a hail of arrows upon the advancing French troops. The muddy terrain hampered the French advance, causing their heavy cavalry to become bogged down, while the agile English soldiers remained more mobile and effective.

Tactical Brilliance of the English

Henry V’s tactical genius became evident as he combined terrain advantage and innovative battlefield strategies. The English longbowmen, who could shoot up to 10 arrows per minute, decimated the French ranks before they could close in for hand-to-hand combat. As the French soldiers struggled through the mud, many fell to the ground, creating a chaotic mass that the English forces exploited. The disciplined English troops, bolstered by their archers, could repel the French charges and maintain their defensive positions.

Turning Point of the Battle

The French suffered catastrophic losses as the battle progressed, and morale plummeted. The turning point came when the French nobility, desperate to turn the tide, charged toward the English lines but faced fierce resistance. Many French knights, encumbered by their heavy armor, fell victim to the longbows or were trapped in the mud. The disarray within the French ranks led to further chaos, and the English seized the opportunity to launch counterattacks, decisively breaking the French advance.

Aftermath of the Battle

The aftermath of Agincourt was devastating for the French, with estimates of casualties ranging from 6,000 to 10,000. The English, on the other hand, suffered relatively few losses, with around 400 to 1,000 men dead. The battle solidified Henry V’s reputation as a military leader and instilled a sense of national pride among the English. The victory at Agincourt boosted English morale and provided a significant advantage in the ongoing conflict, allowing Henry to strengthen his position in France.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

The Battle of Agincourt has left an indelible mark on English history and culture. It has been immortalized in literature, notably in William Shakespeare’s play, Henry V, where King Henry’s inspiring speeches and the valor of his soldiers resonate through time. The battle symbolizes the triumph of determination and strategy over overwhelming odds and has become a rallying point for English nationalism. Agincourt is often remembered not just as a military victory but as a defining moment that shaped the course of the Hundred Years’ War and the future of England.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Battle of Agincourt is a remarkable example of military strategy and leadership. The clash of arms on that October day in 1415 exemplified the complexities of warfare during the Hundred Years’ War and highlighted the significance of morale, tactics, and adaptability in battle. Agincourt remains a testament to the resilience of the English forces and continues to inspire generations through its stories of courage, sacrifice, and national identity.

Battle of Tenochtitlán (1521, Mexico)

During the siege of Tenochtitlan, Hernan Cortés narrowly escaped capture by Aztec warriors—detail of a painting at the Museo de América, Madrid, Spain (Wiki Image).

“The Torture of Cuauhtémoc,” a 19th-century painting by Leandro Izaguirre (Wiki Image).

Ten notable quotes:

Here are ten quotes related to the Battle of Tenochtitlán (1521):

- Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a Spanish soldier and chronicler:

“We could not walk without treading on the bodies and heads of dead Indians; I have never seen such a thing before nor heard it spoken of.” - Hernán Cortés, leader of the Spanish conquest:

“We have arrived at the very heart of the enemy’s power, and though it is defended with fury, we shall prevail with God’s grace and our men’s determination.” - Francisco López de Gómara, Spanish historian:

“Tenochtitlán was the greatest city in the world. Its fall was an event unparalleled in human history.” - Aztec account from the Florentine Codex:

“Broken spears lie in the roads; we have torn our hair in our grief. The houses are roofless now, and their walls are red with blood.” - Moctezuma II, before his capture:

“I am no longer the master of myself, nor of my house. I shall never again enjoy the throne of my ancestors.” - Diego Durán, Dominican friar and chronicler:

“The Spaniards came like a plague; they showed no mercy and brought the empire to its knees.” - Cuitláhuac, Aztec ruler, rallying his warriors:

“Brothers, let us not succumb to despair. Let the fury of Huitzilopochtli guide our arms, for we fight not for ourselves but for the gods and the land of our ancestors.” - Cortés, on the Aztec resistance:

“They fought with such valor and resolution, for they preferred to die than see themselves taken alive.” - Ixtlilxochitl, an Indigenous nobleman allied with the Spanish:

“The hour of our ancient enemies has come, and with the help of these foreign lords, we shall reclaim the power that was once ours.” - Father Sahagún, a Franciscan missionary:

“God, in His divine wisdom, chose to cast down the false gods of this land and deliver it into the hands of true believers, though the cost in human life was heavy.”

Casualties

| Forces | Number of Combatants | Casualties (Killed/Wounded) | Prisoners | Ships Involved | Ships Lost |

| Spanish & Tlaxcalan Allies | ~1,500 Spaniards & ~100,000 Tlaxcalan warriors | Spaniards: ~100-200 killed

Tlaxcalans: Thousands killed |

Prisoners: Minimal (Aztec nobility) | 13 brigantines (constructed by the Spanish) | 0 ships lost (brigantines remained intact) |

| Aztec Empire | ~300,000 soldiers & civilians | Casualties: Tens of thousands (combat, disease, starvation) | Prisoners: Emperor Cuauhtémoc captured | Aztec canoes (estimated 4,000) | Most destroyed (in naval combat and sabotage) |

Fall of Tenochtitlan (1521) – Spanish-Aztec War …

The Fall of Tenochtitlan

Tenochtitlan -The Venice of Mesoamerica (Aztec History)

(YouTube video)

The Battle of Tenochtitlán fought in 1521, marked a critical moment in the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. Led by Hernán Cortés, the Spanish forces, alongside their indigenous allies, sought to overthrow the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlán, ruled by Emperor Moctezuma II. This battle was not just a military confrontation but a complex interplay of cultures, politics, and alliances that ultimately led to the fall of one of the most influential civilizations in the Americas.

Background and Context

The early 16th century saw the rise of the Aztec Empire, a dominant force in Mesoamerica. Tenochtitlán, situated on an island in Lake Texcoco, was a magnificent city known for its advanced architecture, extensive trade networks, and vibrant culture. Hernán Cortés arrived in Mexico in 1519 with a small contingent of Spanish soldiers and quickly sought to establish alliances with various indigenous groups discontented with Aztec rule. By leveraging these alliances, Cortés aimed to gather enough forces to challenge the Aztec Empire directly.

Initial Engagements

Cortés’s initial encounters with the Aztecs were fraught with tension. After meeting Moctezuma II, Cortés and his men were welcomed into Tenochtitlán. However, relations soured, and in June 1520, following a series of misunderstandings and confrontations, Cortés was forced to retreat during what became known as the Noche Triste (Sad Night). This retreat resulted in significant losses for the Spanish, as they fled the city, pursued by Aztec warriors. The event highlighted Spanish ambitions’ precariousness and the Aztec resistance’s strength.

The Siege Begins

Naval assault upon the city (Wiki Image).

After regrouping and securing additional support from indigenous allies, including the Tlaxcalans, Cortés returned to Tenochtitlán in March 1521. The Spanish forces besieged the city, which the Aztecs had reinforced under the leadership of Cuitláhuac, Moctezuma’s successor. The Spanish strategy involved cutting off supplies and reinforcements to the city using their superior artillery to bombard the Aztec defenses. The siege tactics also included blockading the causeways that connected Tenochtitlán to the mainland.

The Role of Indigenous Allies

Cortés’s campaign relied heavily on the support of indigenous allies, who provided vital manpower and knowledge of local geography. The Tlaxcalans, in particular, played a crucial role, contributing thousands of warriors to the Spanish cause. This collaboration showcased the internal divisions within the Aztec Empire, as many indigenous groups resented Aztec domination and sought to reclaim their autonomy. The alliance between the Spanish and these groups transformed the nature of the conflict, making it not solely a Spanish conquest but also a struggle for liberation for many indigenous peoples.

The Final Assault

The siege culminated in a final assault on Tenochtitlán in August 1521. The Spanish forces, alongside their Indigenous allies, launched a coordinated attack on the city. The Spanish forces breached the defenses by utilizing their firearms, horses, and the advantage of surprise. The fierce urban combat ensued with hand-to-hand fighting and brutal street battles. The Spanish and their allies faced determined resistance from the Aztecs, who fought bravely to defend their city.

The Fall of Tenochtitlán

Despite their fierce resistance, the Aztecs were ultimately overwhelmed by the superior weaponry and tactics of the Spanish forces. After weeks of intense fighting, Tenochtitlán fell on August 13, 1521. The city’s capture marked the end of the Aztec Empire and the beginning of Spanish colonial rule in Mexico. The aftermath of the battle was devastating; many Aztecs died from combat, while others succumbed to famine and disease, including smallpox, which the Europeans had inadvertently introduced.

Aftermath and Consequences

The fall of Tenochtitlán had profound consequences for both the indigenous populations and the Spanish Empire. Cortés established Mexico City on the ruins of Tenochtitlán, transforming it into the capital of Spanish colonial rule in the Americas. The defeat of the Aztecs marked a significant shift in power dynamics in Mesoamerica and set the stage for further Spanish conquests across the continent. The cultural and demographic impact of the conquest would be felt for centuries as indigenous societies faced profound disruptions and transformations.

Legacy of the Battle

The Battle of Tenochtitlán remains a significant historical event, symbolizing the clash of civilizations and the consequences of imperial ambition. It serves as a reminder of the complex interactions between Europeans and indigenous peoples during the Age of Exploration. The narrative of the battle has been subject to reinterpretation, with historians exploring themes of resistance, cultural exchange, and the long-lasting effects of colonization. The fall of Tenochtitlán changed the course of Mexican history and had lasting implications for the Americas and the world, highlighting the intricate web of conquest, survival, and adaptation that defines human history.

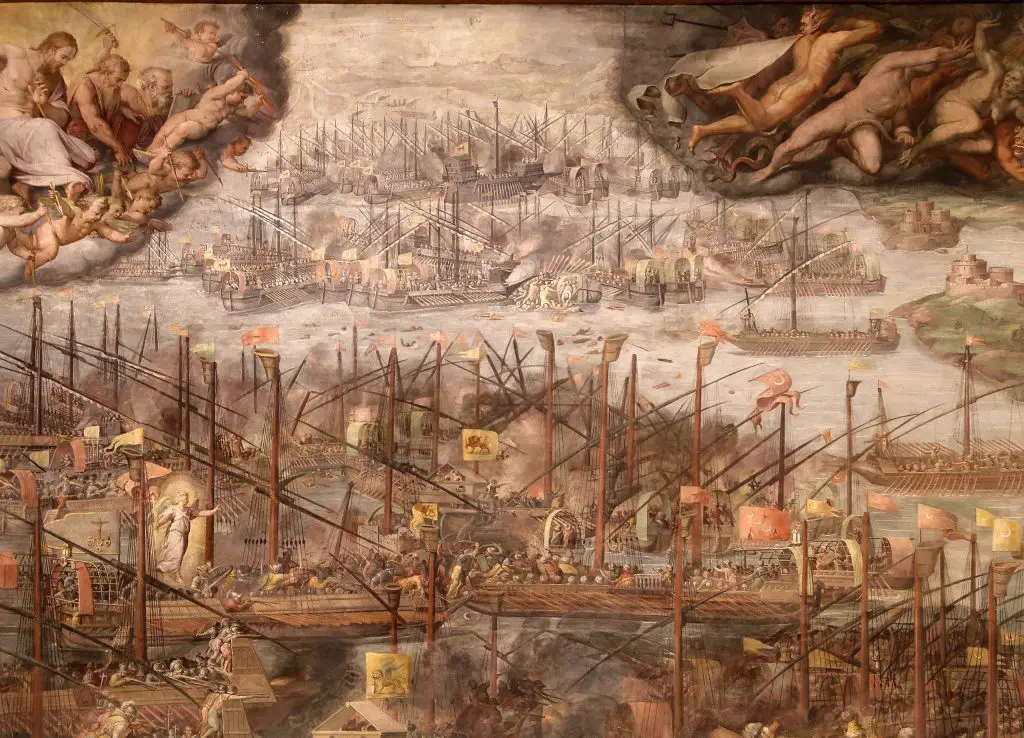

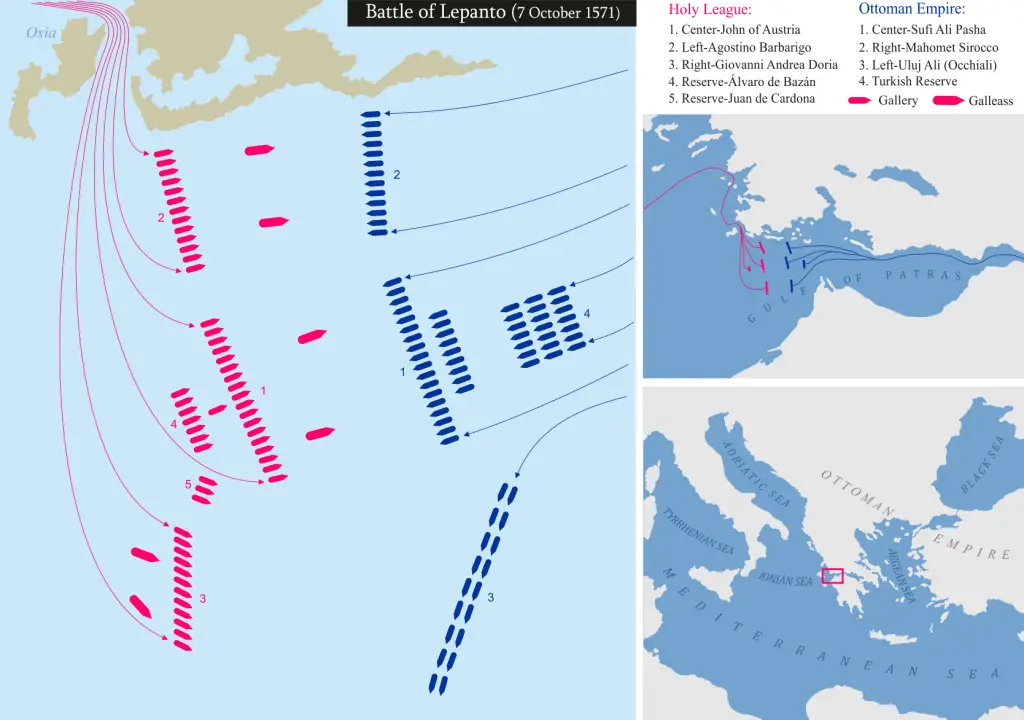

Battle of Lepanto (1571, Mediterranean)

Battle of Lepanto by Martin Rota, 1572 print, Venice (Wiki Image).

The Battle of Lepanto by Giorgio Vasari (WIki Image).

Ten notable quotes:

Here are ten quotes related to the Battle of Lepanto (1571), a historic naval battle between the Holy League and the Ottoman Empire:

- Miguel de Cervantes (famous author of Don Quixote, who fought in the battle):

- “That day, so happy for Christendom, for all the peoples of the world, and for me, because I was present at the conflict.”

- Pope Pius V (who organized the Holy League against the Ottomans):

- “The Christian fleet has triumphed! Thanks be to God!” (on hearing news of victory)

- John Julius Norwich (historian):

- “Lepanto was a victory of the Cross over the Crescent, a decisive battle that halted the Ottoman advance in the Mediterranean.”

- G.K. Chesterton (poet, from Lepanto):

- “Dim drums throbbing, in the hills half heard, / Where only on a nameless throne a crownless prince has stirred.”

- Philip II of Spain:

- “I sent you out to fight the enemy, not the weather.” (reportedly in frustration over delays due to weather conditions before the battle)

- Ali Pasha (Ottoman admiral before the battle):

- “If Allah is with us, what can men do against us?”

- Venetian chronicler:

- “It was as if the entire sea caught fire.” (describing the intensity of the fighting)

- Cervantes (again reflecting on the battle):

- “The greatest occasion seen for centuries past.”

- Pope Pius V (after the victory):

- “It was not generals, it was not battalions, but the Mother of God who has made us victors.”

- Ottoman soldier’s lament:

- “The infidels overwhelmed us with their strange iron ships and terrible fury.”

Casualties

| Force | Commander | Ships (Start) | Men (estimated) | Killed/Wounded | Prisoners | Ships Lost/Captured |

| Holy League | Don John of Austria | 206 | ~84,000 | 15,000 – 20,000 | 3,500 | 12 lost, 117 captured |

| Ottoman Empire | Uluç Ali Pasha | 230 | ~88,000 | 20,000 – 30,000 | 8,000 | ~210 lost/captured |

Export to Sheets

Battle of Lepanto 1571 – Ottoman Wars DOCUMENTARY

Lepanto 1571: Shattering the Idea of Ottoman Invincibility

Battle of Lepanto, 1571: What REALLY Happened

(YouTube video)

The Battle of Lepanto, fought on October 7, 1571, was a pivotal naval engagement between the Holy League, a coalition of Catholic maritime states, and the Ottoman Empire. This battle marked a significant turning point in the struggle for dominance over the Mediterranean Sea. The Holy League’s victory not only halted the Ottoman expansion into Europe but also had lasting effects on the balance of power in the region.

Background and Context

Under Sultan Selim II’s rule, the Ottoman Empire expanded its influence throughout the Mediterranean during the 16th century. By the mid-1500s, the Ottomans had established control over vast territories, posing a severe threat to Christian states. Pope Pius V called for a coalition of Catholic nations to form the Holy League in response to this encroachment. The League included Spain, the Papal States, Venice, and several smaller Italian states, united by a common cause to repel the Ottoman threat and protect Christendom.

Formation of the Holy League

The formation of the Holy League was a complex and challenging process. It involved negotiations among various powers, each with their agendas and rivalries. The Spanish crown, led by King Philip II, was crucial in assembling the coalition. The Venetians, led by Doge Francesco Venier, were eager to protect their trade routes and territories from Ottoman advances. Despite initial disagreements and conflicts of interest, the coalition was finally formed, with a combined fleet under the command of Don Juan of Austria, half-brother of King Philip II.

The Forces at Lepanto

The fleet of the Holy League comprised approximately 200 ships and around 30,000 men, including soldiers and sailors. The flagship, the Real, was a heavily armed galleass. The Ottoman fleet, commanded by Ali Pasha, was more numerous, consisting of around 330 vessels and an estimated 35,000 to 40,000 men. The Ottomans had a well-established naval tradition, but the quality of their ships and crews varied. The battle’s outcome would depend not only on the size of the fleets but also on tactics, leadership, and the determination of the crews.

The Battle Begins

Plan of the Battle (formation of the fleets just before contact) (Wiki Image).

The two fleets met in the Gulf of Patras near the city of Lepanto. Early in the morning, the Holy League initiated the engagement with a powerful artillery bombardment. The Ottomans responded with cannon fire, and the battle quickly descended into chaos as the ships clashed in close combat. The Holy League’s lighter and more maneuverable galleys gained an advantage over the heavier Ottoman ships, which struggled to operate effectively in the confined waters of the Gulf.

Turning Point and Tactics

As the battle raged on, several key factors influenced the outcome. The skillful maneuvering of the Holy League’s galleys allowed them to break the Ottoman line. Don Juan of Austria demonstrated exceptional leadership, coordinating his forces effectively and maintaining morale among his sailors. The use of artillery proved decisive, with the Holy League’s ships equipped with powerful cannons that severely damaged the Ottoman vessels. The Ottomans, facing fierce resistance and high casualties, began to falter.

Ottoman Defeat and Aftermath

The tide of the battle turned in favor of the Holy League, leading to a decisive victory. The Ottomans lost around 200 ships, while the Holy League suffered significantly fewer losses, estimated at about 50 ships. Ali Pasha was killed in battle, and many Ottoman soldiers were captured or drowned as their fleet disintegrated. The victory at Lepanto was celebrated throughout Europe as a triumph for Christendom and marked the beginning of a decline in Ottoman naval power.

Impact on the Mediterranean Balance of Power

The Battle of Lepanto had far-reaching consequences for the Mediterranean geopolitical landscape. The defeat significantly weakened the Ottoman navy, forcing them to adopt a more defensive posture in subsequent years. Although the Ottomans remained a formidable land power, their inability to project naval power effectively limited their influence in maritime conflicts. The victory of the Holy League emboldened Christian states and invigorated their resistance against Ottoman expansion.

Cultural Significance and Legacy

The Battle of Lepanto inspired a wave of cultural and artistic expression. It symbolized the struggle between Christianity and Islam, often depicted in literature, paintings, and even operas. Notable artists, such as El Greco, created works celebrating the victory. The battle’s significance is reflected in its commemoration within the Catholic tradition, with the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary established to honor the triumph attributed to divine intervention. The legacy of Lepanto serves as a reminder of the complex interplay of power, religion, and culture in shaping European history during the Age of Exploration.

In summary, the Battle of Lepanto was a landmark event that marked a turning point in the Ottoman Empire’s naval dominance and had profound implications for the broader geopolitical landscape of Europe and the Mediterranean. The victory underscored the importance of unity among Christian states in the face of a common threat and left an enduring legacy in cultural and religious history.

Spanish Armada (1588, England Channel)

Defeat of the Spanish Armada, 8 August 1588, painted by Philip James de Loutherbourg (1796) (Wiki Image).

The Surrender of Pedro de Valdés (commander of the Squadron of Andalusia) to Francis Drake aboard the Revenge during the attack of the Spanish Armada, 1588, by John Seymour Lucas (Wiki Image).

Ten notable quotes:

Here are ten quotes related to the Spanish Armada (1588, English Channel), one of the most famous naval encounters between Spain and England:

- Queen Elizabeth I (in her famous speech to the troops at Tilbury):

- “I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king and of a king of England, too.”

- King Philip II of Spain:

- “I sent the Armada against men, not God’s winds and waves.” (after the Armada’s defeat)

- Sir Francis Drake (English admiral, in response to the Spanish approach):

- “There must be a beginning of any great matter, but the continuing unto the end until it be thoroughly finished yields the true glory.”

- Anonymous Spanish officer:

- “The whole bay was on fire like the heavens had rained hell upon us.”

- Sir Walter Raleigh (reflecting on the aftermath):

- “The Invincible Armada had more of the wind and the waves to contend with than the swords of Englishmen.”

- Luis de Córdova (Spanish commander):

- “We fight not only against the English but against the elements themselves.”

- Sir John Hawkins (English commander):

- “God has breathed on them, and they are scattered.” (regarding the storm that helped defeat the Armada)

- Pope Sixtus V:

- “Had I but known that the fleet would be so ruined by winds, I would not have so cheerfully contributed funds for its voyage.”

- Sir Martin Frobisher (English vice admiral):

- “With God’s favor and the skill of our mariners, we have scattered the pride of Spain upon the sea.”

- Contemporary English ballad:

- “With an invincible navy they came, / Threatening fire and the sword, / But by the breath of God they were swept away, / The proud Armada of Spain.”

Casualties

| Forces | Number of Combatants | Casualties (Killed/Wounded) | Prisoners | Ships Involved | Ships Lost |

| Spanish Armada | ~30,000 soldiers & sailors | Casualties: ~20,000 (various causes) | Prisoners: Few survivors captured | 130 ships | 63 ships lost (sunk, wrecked, captured) |

| English Navy | ~15,000 sailors & soldiers | Casualties: ~100 dead, ~400 wounded | Prisoners: N/A | 200 ships (mostly smaller) | 0 ships lost |

History Of Warfare – The Spanish Armada – Full Documentary

The Untold Story Of The Spanish Armada: The Truth Behind …

Spanish Armada: How England Defended Itself – Early …

(YouTube video)

The Spanish Armada, launched in 1588, is one of history’s most famous naval conflicts. It marked a pivotal moment in the struggle between England and Spain during the late 16th century. This colossal fleet, comprising around 130 ships, was sent by King Philip II of Spain to invade England and restore Catholicism after a period of Protestant rule under Queen Elizabeth I. The event is often remembered for its dramatic battles and the shifting tides of power in Europe.

Background

The roots of the Spanish Armada can be traced to the religious and political tensions between Catholic Spain and Protestant England. Elizabeth I’s accession to the throne in 1558 heightened these tensions, mainly as she supported Protestant causes in Europe and authorized raids on Spanish ships and territories. The execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, in 1587 further inflamed Philip II, who viewed Elizabeth as an illegitimate ruler and a usurper of the Catholic faith. Determined to eliminate Protestantism in England and reassert Spanish dominance, Philip prepared a massive fleet for invasion.

The Armada’s Composition

The Armada was an impressive assembly of ships, including galleons, transport ships, and support vessels. It was designed to carry soldiers for the invasion and protect the fleet during its journey. Commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, the fleet aimed to transport about 30,000 troops across the Channel to England, where they would unite with English Catholics to dethrone Elizabeth. However, the Armada was plagued by logistics, supply, and coordination issues, which later contributed to its downfall.

The Initial Plan

The original plan for the Armada involved a coordinated attack on England. The Spanish fleet would sail to the Netherlands, picking up additional troops. From there, the combined forces would invade England. However, the plan quickly ran into complications, including delays due to poor weather and the loss of ships during its assembly. Despite these setbacks, Philip II was determined to proceed, convinced that England’s defeat was imminent.

The Encounter with the English Fleet

Route of the Spanish Armada (Wiki Image).

The Armada set sail in May 1588. The English, led by Admiral Sir Francis Drake and other naval commanders, were prepared for a confrontation. The English fleet engaged the Spanish in skirmishes using faster, more maneuverable ships. The English ships employed tactics such as “hit-and-run” attacks, targeting the Spanish galleons, which were heavily armed but slower and less agile. This naval warfare demonstrated the effectiveness of the English tactics against the traditional Spanish approach.

The Battle of Gravelines

The most significant clash occurred on July 29, 1588, at the Battle of Gravelines. The English fleet launched a fierce assault on the Armada, employing their superior speed and artillery. The battle significantly damaged the Spanish ships, with several vessels sunk or disabled. The English inflicted heavy casualties, demonstrating their naval prowess and strategic superiority. The Duke of Medina Sidonia faced tremendous challenges maintaining order and coordination among the Armada’s ranks, leading to confusion and disorder.

The Storm and the Retreat

Following the battle, the Spanish fleet faced another disaster: a severe storm that battered their ships as they attempted to return to Spain. Known as the “Protestant Wind,” this tempest wreaked havoc on the already weakened Armada, scattering ships and forcing many to run aground or sink. The storm compounded the losses suffered in battle, further decimating the fleet. By the time the remnants of the Armada returned to Spain, only a fraction of the original fleet remained.

Consequences of the Armada

The defeat of the Spanish Armada had profound implications for both Spain and England. For Spain, it marked the beginning of a gradual decline in its naval power and influence, leading to a shift in the balance of power in Europe. The loss tarnished Philip II’s reputation and diminished Spanish sea dominance. For England, the victory solidified Elizabeth I’s position and bolstered national pride, reinforcing the Protestant cause. It also inspired a new wave of naval exploration and expansion as England emerged as a formidable maritime power.

Historical Legacy

The Spanish Armada remains a symbol of the clash between two powerful empires and the changing dynamics of European politics in the late 16th century. Its legacy continues in discussions of naval warfare, imperial ambition, and religious conflict. The events surrounding the Armada have inspired countless works of literature and historical analysis, serving as a reminder of the complexities of war, strategy, and the unpredictable nature of fortune at sea.

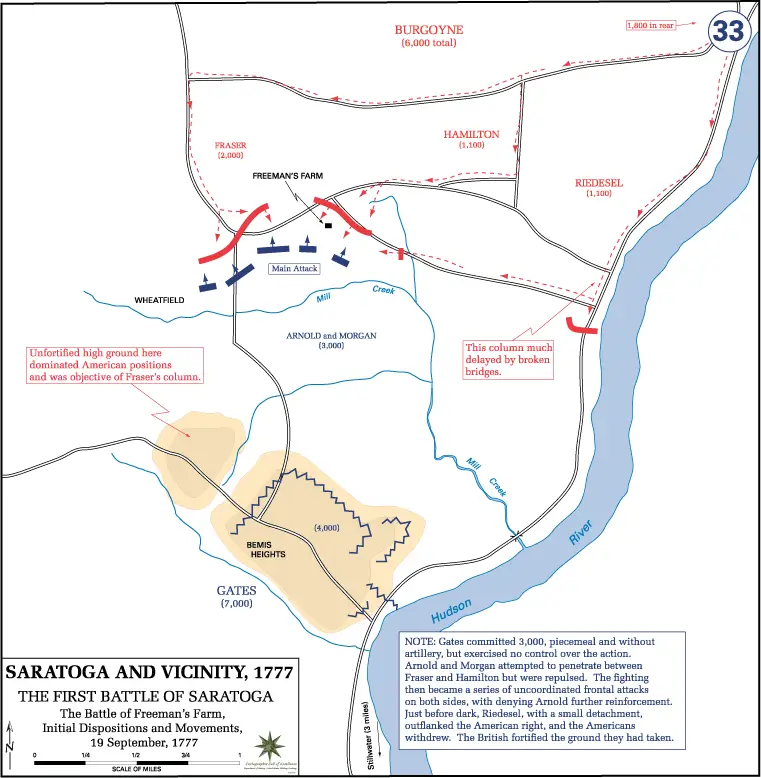

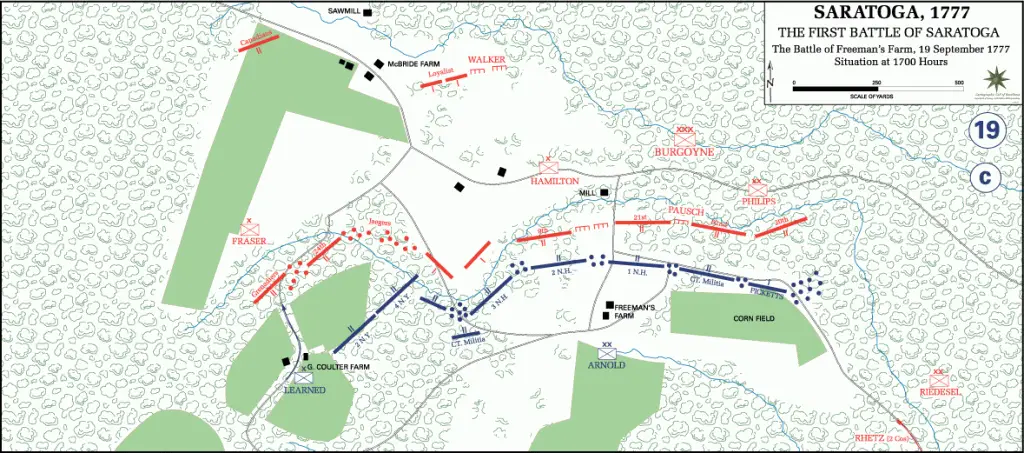

Battles of Saratoga (1777, America)

Surrender of General Burgoyne is an 1822 portrait by John Trumbull of a British Army general surrendering to General Horatio Gates, who refused to take his sword. The painting presently hangs in the United States Capitol Rotunda (Wiki Image).

Ten notable quotes:

Here are ten quotes related to the Battles of Saratoga (1777, America), a turning point in the American Revolutionary War:

- General John Burgoyne (British commander, before surrendering):

- “The fortunes of war have made me your prisoner.” (to General Gates after the British defeat)

- General Horatio Gates (American commander):

- “The Almighty has been pleased to grant us another signal victory.”

- General Benedict Arnold (American commander during the battle):

- “Victory or death!” (leading a charge at Bemis Heights)

- Henry Clinton (British general, on the lack of reinforcements):

- “I can do no more. The game is up.”

- American soldier’s diary:

- “The sight of Burgoyne’s army laying down their arms was a noble spectacle indeed, and it made our hearts swell with joy.”

- Benjamin Franklin (on the French reaction to Saratoga):

- “This event will, I hope, encourage our European friends to stand by us with vigor.”

- Sir Henry Clinton (British commander, frustrated by lack of coordination):

- “I could do nothing to assist Burgoyne. His fate was sealed long before we even heard of his needs.”

- Thomas Paine:

- “Saratoga was the turning point of the American Revolution, for it brought France into the war, and with it, victory.”

- King George III:

- “We must be resigned to our misfortune, but I hope it will soon be remedied by the speediest exertions.” (after learning of Burgoyne’s surrender)

- Marquis de Lafayette (French general on the significance of Saratoga):

- “This victory has been the greatest joy for our allies, and it lights the flame of freedom across the seas.”

Casualties

| Forces | Number of Combatants | Casualties (Killed/Wounded) | Prisoners |

| American Continental Army | ~12,000-15,000 | Killed/Wounded: ~500-800 | Prisoners: 0 |

| British Army (incl. German Hessians) | ~8,000 | Killed/Wounded: ~1,200 | Prisoners: ~5,800 (surrendered) |

American Revolution: The Battle of Saratoga, 1777

The Battle of Saratoga and “the Compleat Victory” | Kevin …

Battle of Saratoga: A Turning Point in the Revolutionary War

(YouTube video)