The World Fairs History Table

Here are clean, organized tables of World’s Fair history, covering the major expos, grouped by century and including themes, locations, and signature achievements.

If you want, I can expand these into a printable PDF or add more fairs.

🌍 World’s Fairs History – Master Tables

1. 19th Century World’s Fairs (1851–1900)

| Year | City | Official Name | Theme / Purpose | Signature Structure | Key Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1851 | London | Great Exhibition | Industrial progress & global manufacturing | Crystal Palace | First world’s fair; industrial machines; global trade exhibit |

| 1855 | Paris | Exposition Universelle | Arts, agriculture, industry | Palais de l’Industrie | Rise of French industrial prestige |

| 1862 | London | International Exhibition | Progress in arts & industry | Western Annex | Textiles, telegraphy |

| 1867 | Paris | Exposition Universelle | National pavilions (first time) | Oval iron-and-glass palace | Cultural exchange innovation |

| 1873 | Vienna | Weltausstellung | Industry & modern cities | Rotunde | Urban planning focus |

| 1876 | Philadelphia | Centennial Exhibition | 100 years of U.S. industry | Memorial Hall | Telephone debut; typewriter |

| 1878 | Paris | Exposition Universelle | Third Republic prestige | Trocadéro Palace | Electric lighting displays |

| 1880 | Melbourne | International Exhibition | Colony development | Royal Exhibition Bldg | Largest 19th-century building in Aus |

| 1889 | Paris | Exposition Universelle | French Revolution centennial | Eiffel Tower | Modern engineering revolution |

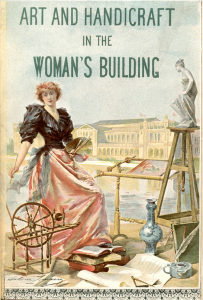

| 1893 | Chicago | Columbian Exposition | 400 years after Columbus | Ferris Wheel, “White City” | AC electricity; City Beautiful movement |

| 1900 | Paris | Exposition Universelle | New century optimism | Grand Palais, Petit Palais | Moving sidewalks; escalators |

2. Early 20th Century Fairs (1901–1938)

| Year | City | Official Name | Theme | Signature Structure | Key Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1904 | St. Louis | Louisiana Purchase Expo | Expansion & technology | Festival Hall | X-ray displays; the ice cream cone popularized |

| 1910 | Brussels | Exposition Universelle | International culture | Colonial Palace | Belgium’s global ambitions |

| 1929–30 | Barcelona | International Exposition | Art & architecture | Mies Pavilion | Birth of modernist architecture |

| 1933–34 | Chicago | Century of Progress | Science & industry | Sky Ride | Art Deco + technology fusion |

| 1935 | Brussels | Exposition Universelle | Modern culture | Palais du Centenaire | Urban development |

| 1937 | Paris | Exposition Internationale | Art & technology | Soviet & German pavilions | Picasso’s Guernica displayed |

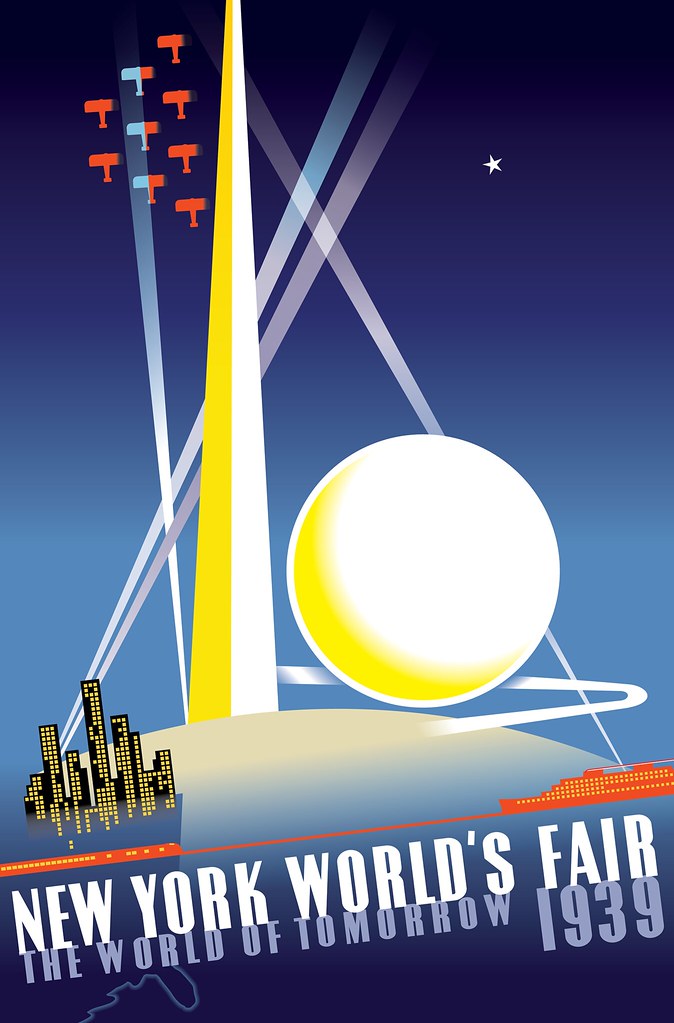

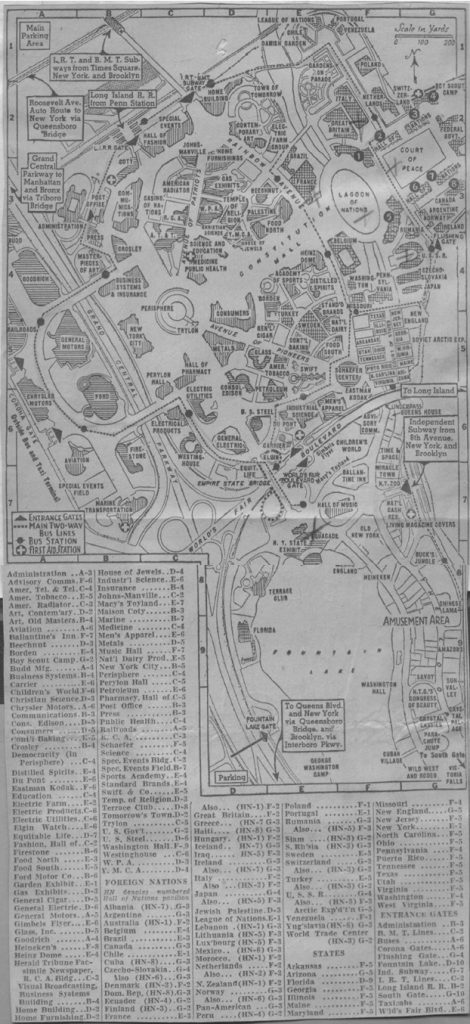

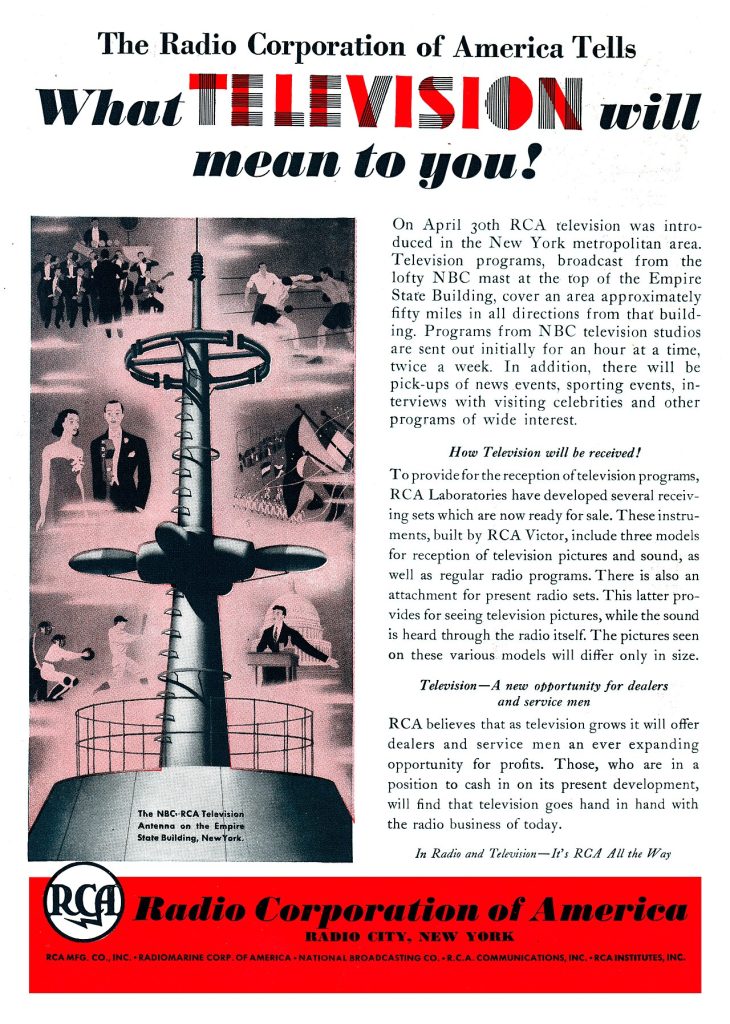

| 1939–40 | New York | World of Tomorrow | Futurism, consumer tech | Trylon & Perisphere | Public debut of TV; modernist future vision |

| 1940 | San Francisco | Golden Gate Expo | Pacific unity | Treasure Island buildings | West Coast technology |

3. Mid-Late 20th Century Fairs (1950–1999)

| Year | City | Official Name | Theme | Signature Structure | Key Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1958 | Brussels | Expo 58 | Atomic Age | Atomium | First postwar expo; Cold War science |

| 1962 | Seattle | Century 21 Expo | Space Age | Space Needle | Futurism, monorails |

| 1964–65 | New York | World’s Fair | Peace & progress | Unisphere | Robotics, space tech |

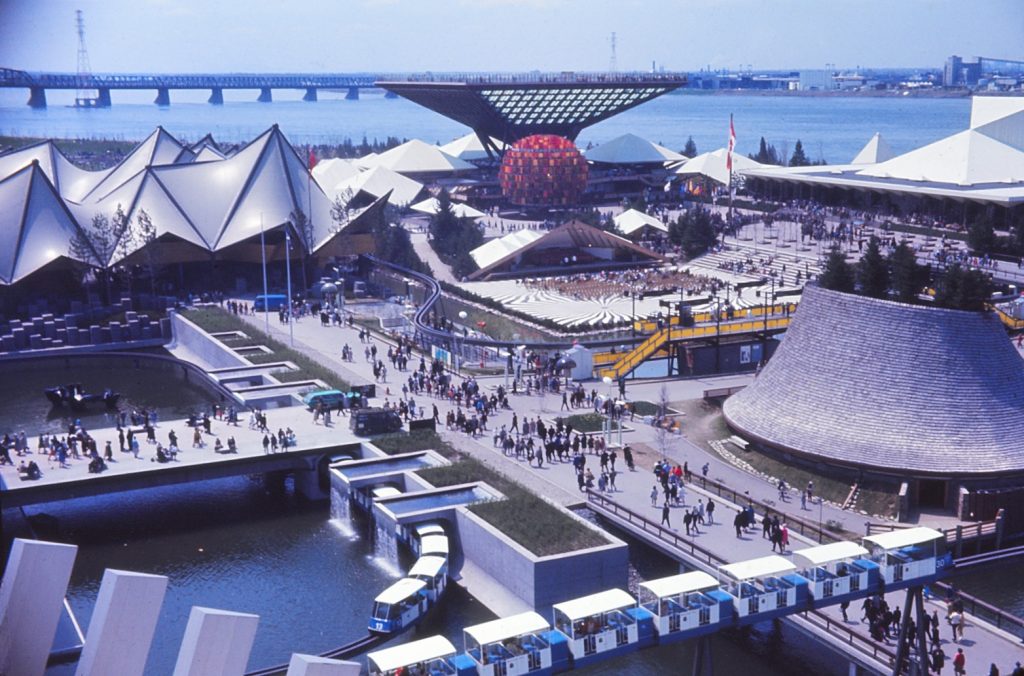

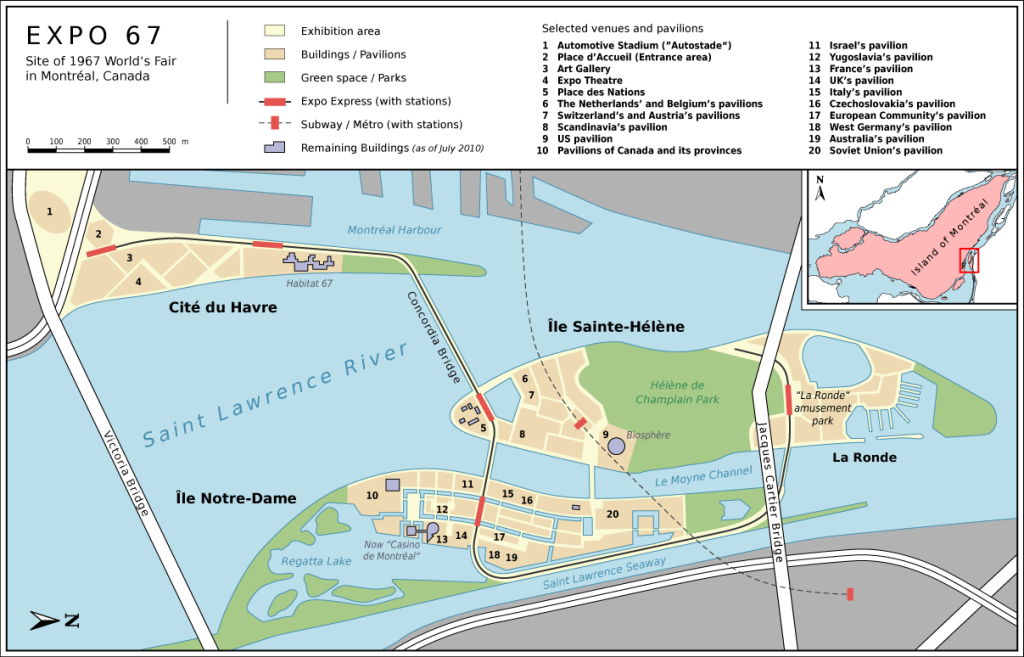

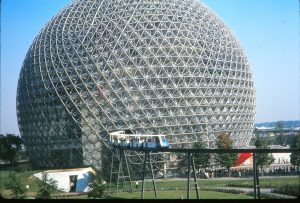

| 1967 | Montreal | Expo 67 | “Man and His World” | Geodesic Dome, Habitat 67 | One of the most successful expos ever |

| 1970 | Osaka | Expo ’70 | Progress & harmony | Tower of the Sun | First World Fair in Asia |

| 1992 | Seville | Universal Exposition | Discoveries of the world | Bridges & pavilions | Cultural exchange |

| 1998 | Lisbon | Expo ’98 | Oceans & exploration | Oceanarium | Marine science focus |

4. 21st Century World’s Fairs (2000–Present)

| Year | City | Theme | Signature Structure | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Aichi (Japan) | Nature’s wisdom | Global House | Sustainability emphasis |

| 2010 | Shanghai | Better city, better life | China Pavilion | Largest expo ever |

| 2015 | Milan | Feeding the planet | Tree of Life | Food systems & sustainability |

| 2020 (held 2021–22) | Dubai | Connecting minds | Al Wasl Dome | First expo in the Middle East |

| 2025 | Osaka | Designing a future society | Floating ring arena | Theme: “Saving Lives” |

Want More?

I can make any of the following:

📊 A single giant comparison table

🗺️ A map showing expo locations over time

📘 A blog-ready article on World’s Fairs

📄 A printable PDF document

📅 A chronological timeline chart

Just tell me your preferred format!

The Five Greatest World Fairs

While “greatest” is subjective, the most influential World’s Fairs are those that set a new standard, left behind a world-famous icon, or captured a pivotal moment in history.

Here are five of the greatest and most transformative World’s Fairs.

1. 🏛️ London 1851: The Great Exhibition

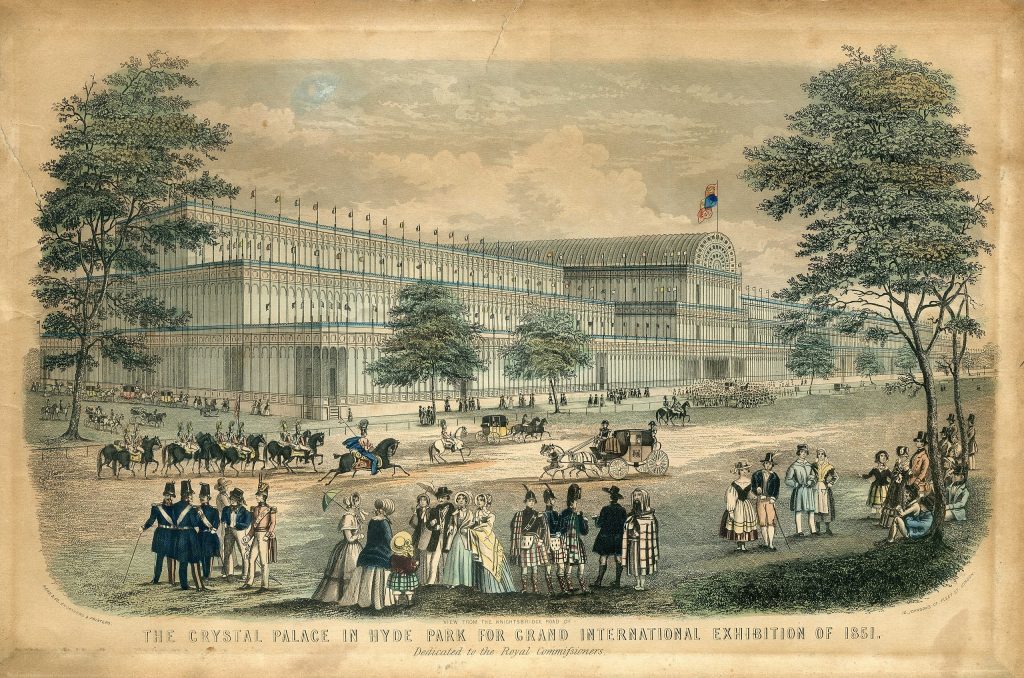

Theme: “Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations” Icon: The Crystal Palace

This was the first true international World’s Fair, and it set the template for all others. Housed in the revolutionary Crystal Palace—a massive structure of cast iron and glass—it was a celebration of the Industrial Revolution. It showcased the best of manufacturing, science, and art, establishing the fair as a venue for nations to display their technological prowess and cultural identity.

2. 🗼 Paris 1889: Exposition Universelle

Theme: Celebrating the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution Icon: The Eiffel Tower

This fair is famous for giving the world its most recognizable landmark. The Eiffel Tower served as the exposition’s grand entrance arch and was a staggering feat of engineering, becoming the tallest man-made structure in the world. The fair showcased the wonders of the new “Age of Steel” and electricity, firmly establishing Paris as a global center of art and technology.

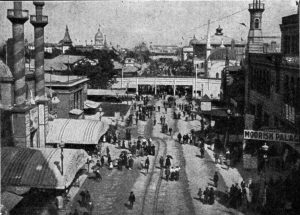

3. 🎡 Chicago 1893: World’s Columbian Exposition

Theme: Celebrating the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival Icon: The “White City” and the original Ferris Wheel

This fair was a profound moment for America. It was a massive, elaborately designed fairground known as the “White City,” featuring gleaming white neoclassical buildings that launched the “City Beautiful” architectural movement across the United States. It also introduced major technological innovations to the public, including the first-ever Ferris Wheel and the widespread adoption of alternating current electricity, both showcased by Westinghouse.

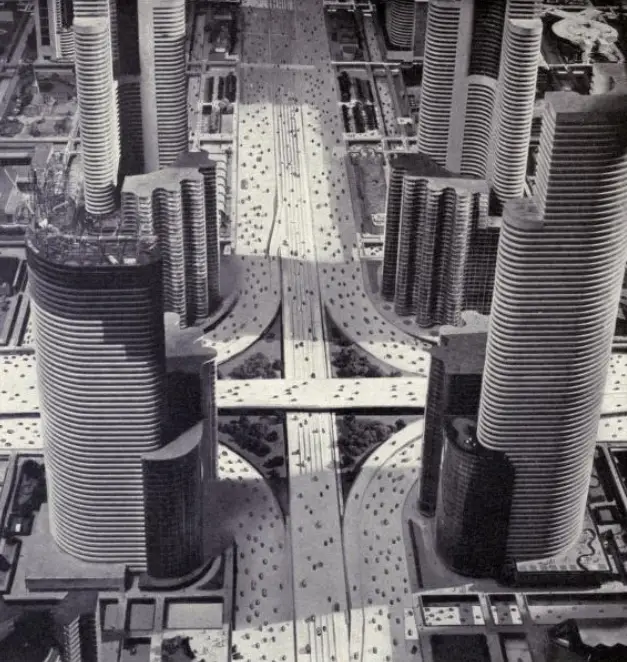

4. 🚀 New York 1939-40: The World of Tomorrow

Theme: “Building the World of Tomorrow” Icon: The Trylon and Perisphere

Opening just months before the start of World War II, this fair was a spectacular, optimistic vision of the future. Its most famous exhibits, General Motors’ “Futurama” and the “Democracity” diorama, presented a new American dream built around superhighways, suburbs, and consumer technology. It was less about present-day achievements and more about a utopian blueprint for the post-war world, which heavily influenced the 1950s.

5. 🌍 Montreal 1967: Expo 67

Theme: “Man and His World” Icon: Habitat 67 and the Geodesic Dome

Often cited as the most successful and optimistic World’s Fair of the 20th century, Expo 67 celebrated Canada’s centennial. It was a cultural and architectural triumph. It featured the U.S. pavilion, a massive geodesic dome designed by Buckminster Fuller, and the revolutionary Habitat 67 housing complex, which re-imagined urban living. The fair’s hopeful, humanist theme and vibrant atmosphere perfectly captured the spirit of the 1960s.

🏛️ London 1851: The Great Exhibition

View from the Knightsbridge Road of The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park for the Grand International Exhibition of 1851. Dedicated to the Royal Commissioners., London: Read & Co. Engravers & Printers, 1851.

(Wiki Image By Read & Co. Engravers & Printers – View from the Knightsbridge Road of The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park for the Grand International Exhibition of 1851. Dedicated to the Royal Commissioners., London: Read & Co. Engravers & Printers, 1851., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=48718934)

🏛️ London 1851: The Great Exhibition Quotes

Here are some of the most famous and representative quotes from and about the 1851 Great Exhibition, capturing the event’s sense of wonder, industrial purpose, and cultural impact.

🏛️ Queen Victoria (From her personal diary)

Queen Victoria’s diary entry for the opening day, May 1, 1851, is the most famous first-hand account, filled with emotion and awe.

“This day is one of the greatest and most glorious days of our lives, with which, to my pride and joy, the name of my dearly beloved Albert is forever associated!

…The sight as we came to the centre, where the steps and chair… were placed, facing the beautiful crystal fountain, was magic and impressive. The tremendous cheering, the joy expressed in every face, the vastness of the building, with all its decorations and exhibits… and my beloved Husband, the creator of this great ‘Peace Festival,’ uniting the industry and art of all nations of the earth.

God bless my dearest Albert, and my dear Country, which has shown itself so great today.”

👑 Prince Albert (The Organizer)

In a 1850 speech, Prince Albert, the chief organizer, laid out his grand, idealistic vision for the exhibition’s purpose.

“We are living in a period of the most wonderful transition… The distances which separate the different nations and parts of the globe are rapidly vanishing…

I therefore conceive it to be the duty of every educated person to close… the Utopian dream of the ‘Unity of Mankind’… The Exhibition of 1851 is to give us an actual test and a living picture of the point of development at which the whole of mankind has arrived… and a new starting-point from which all nations will be able to direct their further exertions.”

✍️ Charles Dickens (The Overwhelmed Visitor)

The novelist Charles Dickens, known for his critiques of industrial society, captured the exhibition’s overwhelming, almost maddening scale in a letter.

“I find I am ‘used up’ by the Exhibition. I don’t say ‘there’s nothing in it’ — there’s too much. I have only been twice. So many things bewildered me. I have a natural horror of sights, and the fusion of so many sights in one has not decreased it.”

🕊️ The Duke of Wellington (The Pragmatist)

This famous anecdote illustrates the practical problems of the Crystal Palace. When Queen Victoria complained that birds were nesting in the enormous elm trees enclosed within the hall, she asked the aged Duke of Wellington for advice. His curt, practical solution has become legendary.

“Try sparrowhawks, Ma’am.”

📰 Contemporary Press

A contemporary writer for the Great Exhibition Prize Essay (1851) summed up the immense public excitement and scale of the event:

“We are upon the eve of an event which may certainly be looked upon as the greatest wonder of the world.”

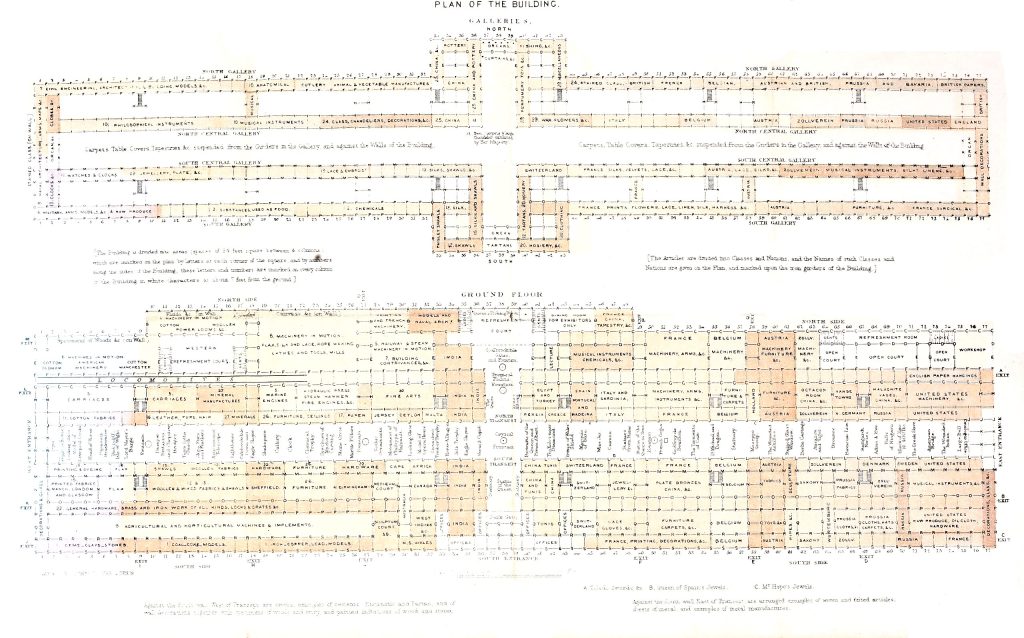

🏛️ London 1851: The Great Exhibition History

Plan of the exhibition

(Wiki Image By Unknown – Plan of the building, Great Exhibition, 1851, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=169686221)

Here’s the history of the 1851 Great Exhibition.

The First World’s Fair

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations was the first international “World’s Fair.” It was a massive cultural and industrial spectacle designed to showcase the technological wonders and manufactured goods of the age.

The Organizers and Purpose

The event was the brainchild of Prince Albert (Queen Victoria’s husband) and Henry Cole, a civil servant and inventor. Their primary goals were to:

- Celebrate the Industrial Revolution: It was a grand stage for the new technologies in steam, manufacturing, and science.

- Assert British Superiority: While it invited “all nations,” the exhibition was explicitly designed to prove that Great Britain was the undisputed leader in industry, engineering, and commerce.

- Promote Free Trade: It was a celebration of global commerce and the idea that open trade would lead to world peace.

The Crystal Palace

The building itself was the main attraction. After a failed design competition, gardener and architect Joseph Paxton submitted a revolutionary plan.

- Design: His building, nicknamed the “Crystal Palace,” was a marvel of pre-fabricated engineering.

- Materials: It was built entirely from cast iron and glass.

- Scale: At 1,851 feet long (a nod to the year), it was a gigantic “glass house” large enough to enclose several fully grown elm trees that were on the site, sparing them from being cut down.

The Exhibition Itself

The fair ran from May 1 to October 15, 1851, in London’s Hyde Park. It was an unprecedented success.

- Exhibits: It featured over 100,000 objects from 14,000 exhibitors, half from Britain and its empire, and half from foreign nations. Wondrous exhibits included:

- The Koh-i-Noor Diamond was recently acquired from India.

- The “Express” Steam Locomotive (the Lord of the Isles).

- The “Greek Slave” statue is a sensational American work of art.

- New technologies like the electric telegraph and the first public, pay-to-use flushing toilets (the “Spending a Penny” origin).

- Attendance: Over six million people (a third of Britain’s population) visited, including figures like Charles Darwin, Charlotte Brontë, and Charles Dickens.

The Legacy

The Great Exhibition was a massive financial success, turning a profit of £186,000 (equivalent to tens of millions in today’s money). This “surplus” was used to create a permanent cultural and educational center in London.

Prince Albert and the Royal Commission used the funds to purchase 87 acres of land in South Kensington. On this land, they founded what would become:

- The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A)

- The Science Museum

- The Natural History Museum

- The Royal Albert Hall

- Imperial College London

The Crystal Palace was dismantled and moved to South London, where it stood as a cultural center for decades until it was destroyed by fire in 1936.

Henry Cole conceived, and Sir Joseph Paxton built the Crystal Palace

Joseph Paxton’s first sketch for the Great Exhibition Building, c. 1850, using pen and ink on blotting paper; Victoria and Albert Museum

(Wiki Image By Original uploader was VAwebteam at en.wikipedia – Transferred from en.wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12829612)

That is the correct way to frame it! They were the dynamic duo behind the 1851 Great Exhibition. It was a partnership of Concept (Cole) and Execution (Paxton).

Here is how their collaboration created the most famous building of the Victorian age.

1. The Problem: “A Wee Bit Behind Schedule.”

By 1850, Henry Cole’s dream of a Great Exhibition was turning into a nightmare.

-

The Deadline: The exhibition was scheduled for May 1, 1851.

-

The Failure: The Building Committee (led by engineers such as Isambard Kingdom Brunel) rejected 245 designs. They eventually produced their own design, a massive brick structure that would have taken years to build and required 30 million bricks.

-

The Crisis: With less than a year to go, they had no building, no plan, and public ridicule was mounting.

2. The Solution: The “Blotting Paper” Sketch

Joseph Paxton was an outsider—a gardener, not an architect. But he had experience building large glasshouses for the Duke of Devonshire (like the Great Stove at Chatsworth).

-

The Meeting: Paxton visited London and heard about the crisis. He told a committee member he could design a building in 9 days.

-

The Sketch: During a railway board meeting on June 11, 1850, while others were talking business, Paxton doodled his idea on a piece of pink blotting paper. It showed a modular structure based on the leaf structure of the giant water lily (Victoria amazonica).

-

The Pitch: Henry Cole immediately recognized the plan’s genius. It was light, cheap, and fast. Cole used his influence to bypass the skeptical committee and get Prince Albert’s approval.

3. The Construction: The “Giant Lego Set.”

Because of Paxton’s modular design and Cole’s organizational skills, the construction was a logistical miracle.

-

Prefabrication: Everything was made in factories in Birmingham and shipped to Hyde Park.

-

300,000 panes of glass.

-

4,500 tons of iron.

-

-

The Glazing Wagons: Paxton invented special trolleys that rode on the roof gutters, allowing workers to install 108 panes of glass per day per man.

-

The Trees: A primary objection was that the park’s elm trees would be cut down. Paxton designed the barrel-vaulted roof (the transept) to be tall enough (108 feet) to enclose the full-grown trees inside the building.

4. The Result

-

Speed: It went from a doodle to a finished building in just 9 months.

-

Size: It was 1,848 feet long (referencing the year 1848) and covered 19 acres.

-

Success: It was the first time the world had seen such a massive enclosed space full of light. It made a profit of £186,000 (which was used to buy the land for the Natural History Museum and V&A).

Summary of the Partnership

-

Henry Cole navigated the politics. He fought the critics, managed the Queen, and kept the committee from killing the project.

-

Joseph Paxton solved the engineering problem. He provided the revolutionary design that made the impossible timeline possible.

Would you like to know about the “Sparrowhawk Problem”—when birds got trapped inside the Crystal Palace and the Queen asked the Duke of Wellington for a solution?

🏛️ London 1851: The Great Exhibition. Eight Wondrous Exhibition

The 1851 Great Exhibition in London was a celebration of the Industrial Revolution, designed to showcase “the Works of Industry of All Nations.” The greatest wonder was arguably the exhibition hall itself: The Crystal Palace.

This revolutionary building, made of cast iron and glass, was a marvel of pre-fabricated architecture. At 1,851 feet long, it was a gigantic greenhouse large enough to enclose fully grown elm trees that were on the site.

Inside, it contained over 100,000 exhibits. Here are eight of the most famous and wondrous exhibits that captivated the six million visitors.

8 Wonders of the Great Exhibition

| Exhibit | Origin | Significance & “Wonder” |

| 1. The Koh-i-Noor Diamond | India / British Empire | This was one of the largest diamonds in the world and the single most popular attraction. Recently acquired by Britain, it was a potent symbol of imperial power. Its poor display, however, led to it being re-cut after the exhibition. |

| 2. The “Express” Steam Locomotive | United Kingdom | A full-size, powerful, 40-ton “Lord of the Isles” locomotive was displayed inside the hall. It was a massive, tangible symbol of the speed, power, and engineering prowess of the new industrial age. |

| 3. The “Greek Slave” Statue | United States | This marble statue by Hiram Powers depicted a nude Greek woman in chains. It was the most famous and controversial artwork at the fair, drawing huge crowds and sparking intense debates about nudity, art, and slavery. |

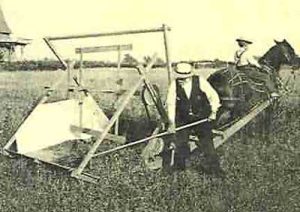

| 4. McCormick’s Reaper | United States | This was a true world-changing invention. The horse-drawn reaping machine could harvest grain far faster than any human, and it won a gold medal, heralding the mechanization of agriculture and the rise of American industrial power. |

| 5. Colt’s Repeating Revolver | United States | Samuel Colt’s display of his new revolving-cylinder firearms was a sensation. It demonstrated the new “American system” of mass production using interchangeable parts, and the pistols became a must-have for adventurous Britons. |

| 6. The Electric Telegraph | United Kingdom | Cooke and Wheatstone’s system was on full display. Visitors were amazed by this “wonder” of instant communication, which allowed messages to be sent from one end of the massive building to the other in seconds. |

| 7. Russian Malachite Doors | Russia | An opulent and non-industrial “wonder.” The Russian exhibit featured a set of colossal, ornate doors and massive urns made from brilliant green malachite. They were a breathtaking display of luxury and natural resources from another empire. |

| 8. The Tempest Prognosticator | United Kingdom | A whimsical and truly “Victorian” invention. It was an elaborate barometer that used live leeches in small jars. When a storm approached, the leeches would become agitated and climb, triggering a small bell. |

London 1851: The Great Exhibition. The Koh-i-Noor Diamond

Queen Victoria wearing the Koh-i-Noor as a brooch, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter

(Wiki Image By Franz Xaver Winterhalter – This image has been extracted from another file, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=100483067)

The Koh-i-Noor (“Mountain of Light”) diamond was arguably the single most famous, popular, and controversial exhibit at the 1851 Great Exhibition. It was its “star attraction,” but its appearance famously underwhelmed the public.

A Symbol of Imperial Power

The diamond’s presence was a raw display of British imperial power. It had been formally surrendered to Queen Victoria just two years earlier (1849) by the Sikh Empire as part of the Treaty of Lahore, which ended the Second Anglo-Sikh War.

Its exhibition in the Crystal Palace was not just a display of a rare gem; it was a potent symbol of Britain’s conquest of India and its status as a global empire.

The Disappointing Display

For all its fame, the public’s reaction was one of mass disappointment.

- Security: The diamond was displayed in a large, ornate, gilt “birdcage” or safe designed by Chubb, the famous locksmith. It was heavily guarded and placed on a velvet cushion.

- The Problem: The gem itself failed to impress. At the time, it had an older, 186-carat “Mughal cut” (its original form). This style had a large, flat top and did not sparkle like modern cuts.

- The Reaction: Under the vast, diffused light of the Crystal Palace, the diamond looked dull, listless, and lifeless. Visitors, expecting a blinding sparkle, complained it looked like a simple piece of glass or “a dull lump of crystal.” The press mocked the lackluster display.

The Aftermath: A Drastic Re-Cutting

The public relations failure of its 1851 exhibition led directly to the diamond’s transformation. In 1852, Prince Albert (Queen Victoria’s husband) ordered that the diamond be re-cut.

This process, which took 38 days and cost £8,000, dramatically altered the stone. It was cut down by over 40% to its current 105.6 carats, but transformed into a much shallower, brilliant-cut oval, giving it the dazzling fire and sparkle the 1851 crowds had expected.

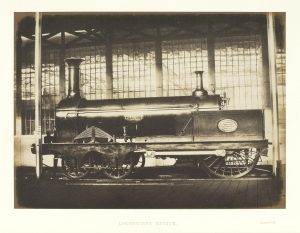

London 1851: The Great Exhibition. The “Express” Steam Locomotive

SER No. 136, Folkstone, with an intermediate crankshaft at the Great Exhibition in 1851.

(Wiki Image By William Henry Fox Talbot – Bonhams, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27547909)

The “Express” steam locomotive you’re referring to was the “Lord of the Isles,” one of the most potent and impressive industrial exhibits at the 1851 Great Exhibition.

It was a massive, 40-ton broad-gauge engine built by the Great Western Railway (GWR). Its presence inside the delicate Crystal Palace was a stunning demonstration of British engineering and the sheer power of the Industrial Revolution.

Why It Was a “Wonder”

- Symbol of Speed and Power: The “Lord of the Isles” was a state-of-the-art “express” engine, built to pull passenger trains at high speeds. It was a tangible, colossal symbol of the new railway age, shrinking the country and changing daily life.

- Engineering Prowess: It was considered the pinnacle of locomotive design at the time. Its sleek design and massive 8-foot-diameter driving wheel represented the height of British industrial might, a key theme of the exhibition.

- A Spectacle of Scale: A significant part of the “wonder” was the audacity of placing a full-size, 40-ton piece of heavy machinery inside the elegant, glass-and-iron exhibition hall. It created a powerful contrast between heavy industry and fine art, all housed under one roof.

The locomotive was so successful as an exhibit that it was awarded a gold medal. It went on to have a long service career with the GWR after the fair concluded.

London 1851: The Great Exhibition. The “Greek Slave” Statue

The Greek Slave by Hiram Powers at the Yale Art Gallery.

(Wiki Image By Karl Thomas Moore – derivative work of File: The Greek Slave by Hiram Powers at Yale.jpg, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=69473799)

“The Greek Slave” was one of the most sensational and talked-about exhibits at the 1851 Great Exhibition. It was a full-size, white marble statue by the American sculptor Hiram Powers.

What It Was

The statue depicted a nude Greek woman, standing in a classical pose, with her hands bound in chains. According to the artist’s narrative, she was a Christian captive of the Ottoman Turks, about to be sold at a slave market. She holds a locket (a cross) in her hand, a symbol of her faith.

Why It Was a “Wonder” (and a Scandal)

- The Nudity: It was a full, frontal female nude, which was a “shock” to the modest Victorian public. This made it an immediate source of scandal and fascination.

- The “Acceptable” Narrative: Powers’s backstory was a brilliant piece of marketing. The statue’s nudity was not portrayed as immodest or erotic; it was a sign of her humiliation and helplessness. Because she was a Christian and her nudity was forced upon her by “infidel” captors, the Victorian audience was given a “moral” reason to gaze at the statue. They could feel pity and righteous indignation, rather than “improper” titillation.

- Mass Popularity: The controversy made it a must-see. It was arguably the most famous single work of art at the exhibition, drawing enormous crowds and endless press coverage. Queen Victoria herself viewed it and approved.

- American Symbolism: As the most prominent American artwork at the fair, it was also a source of national pride. In the U.S., it was sometimes co-opted by abolitionists, who used the image of a white slave to comment on the hypocrisy of American slavery (though Powers himself was not an abolitionist).

London 1851: The Great Exhibition. McCormick’s Reaper

McCormick’s reaper

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – http://www.wynalazki.mt.com.pl/duze/zniwiar.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=847543)

The McCormick Reaper was one of the most significant and world-changing inventions displayed at the 1851 Great Exhibition. It was a horse-drawn machine, invented by Cyrus McCormick, that could harvest grain far faster and more efficiently than human laborers with scythes.

A “Clumsy” Start

When the reaper was first put on display at the Crystal Palace, the British public and press were unimpressed. Compared to the ornate and polished industrial goods of Britain, the American machine looked rough, clumsy, and out of place. The Times of London famously mocked it as “a cross between an Astley’s chariot, a wheelbarrow, and a flying machine.”

The Turning Point: The Field Trial

The exhibition’s organizers, wanting to give the machine a fair chance, arranged for a public field trial at Tiptree Farm outside London. On a damp, drizzly day, the reaper was put to work on a field of wet wheat.

To the crowd’s astonishment, the machine performed flawlessly. It cut a swath of wheat cleanly and quickly, doing the work of over a dozen men. The public’s mockery turned to stunned admiration overnight. The reaper was no longer a joke; it was a revolution.

Significance at the Fair

The McCormick Reaper’s triumph was a pivotal moment.

- It Won a Gold Medal: After its successful demonstration, the reaper was awarded a Council Gold Medal, one of the exhibition’s highest honors.

- It Heralded Mechanized Agriculture: The machine was the single best symbol of the coming mechanization of agriculture, which would change the world by making food cheaper and more plentiful.

- It announced American Ingenuity: The reaper’s success was a turning point for American industry. It proved that the United States was no longer just a rustic backwater but a new, rising industrial power capable of producing practical, world-changing innovations.

London 1851: The Great Exhibition. Colt’s Repeating Revolver

Colt 1851 Navy Revolving Pistol, serial no 2

(Wiki Image By Samuel Colt – This file was donated to Wikimedia Commons as part of a project by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. See the Image and Data Resources Open Access Policy, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65048310)

Samuel Colt’s exhibit of his repeating revolver was one of the most talked-about displays at the Great Exhibition, and it was a sensation for two reasons.

The first, and most obvious, was the gun itself. The Colt Navy revolver was a sleek, powerful, and (most importantly) reliable multi-shot personal weapon. It was seen as a symbol of the rugged American frontier, and its mechanism fascinated the British public.

The Real “Wonder”: Interchangeable Parts

The true marvel of Colt’s exhibit, however, was not just the gun, but how it was made.

At the time, British gunmakers were artisans who hand-filed and fitted every single part. Each gun was a unique, bespoke object, and its parts would not fit any other weapon.

Samuel Colt, by contrast, was a pioneer of the “American system of manufacturing.” He demonstrated that his revolvers were mass-produced using precision machinery, producing thousands of identical, interchangeable parts.

To prove this, Colt famously:

- Disassembled several of his revolvers.

- Mixed all the parts into a jumble on the table.

- Quickly reassembled several working guns from the random pile, with no hand-filing needed.

This demonstration of mass production was a shock to the British industrial establishment. It proved that the United States was a new and serious manufacturing power. Colt’s exhibit was so successful that it won a gold medal, and he was soon invited to open a large Colt factory in London to produce firearms for the British military.

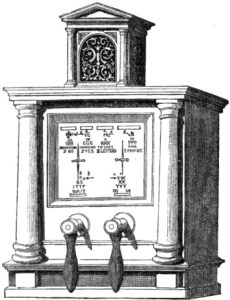

London 1851: The Great Exhibition. The Electric Telegraph

Cooke & Wheatstone’s double-needle telegraph, 1850

https://distantwriting.co.uk/electrictelegraphcompany.html

The electric telegraph was one of the true technological marvels of the 1851 Great Exhibition, representing the “wonder” of instantaneous communication.

It wasn’t a single object but rather a prominent demonstration of a working system. The leading exhibitors were the Electric Telegraph Company, which held the patents for the Cooke and Wheatstone system, the dominant technology in Britain.

Why It Was a “Wonder”

- Instant, “Magical” Communication: For a public that still relied on horse-drawn mail, the idea of sending a message from one place to another in a fraction of a second was pure magic. The exhibit made this abstract idea tangible.

- A Working System: The company didn’t just display the machines; they ran live, working wires throughout the vast Crystal Palace. Visitors could see messages being sent and received in real-time.

- Connecting to the Outside World: The exhibit was connected to the rapidly expanding national telegraph network. This meant the Crystal Palace was, for the first time, in instant communication with major cities across Great Britain. Visitors could see (and in some cases, send) messages to and from London, Edinburgh, Manchester, and other cities, demonstrating the system’s practical power.

- Novelty and “The Future”: Along with the locomotive, the telegraph was the clearest symbol of a new, fast-paced, and interconnected future. It was a significant draw, and the company’s “telegraph office” became a popular meeting point.

The Significance

The telegraph exhibit was a massive commercial and public relations success. It demystified the technology for millions of people and cemented its importance in the public mind. It was no longer a curious scientific toy but a powerful, essential tool for government, commerce, and the press.

It’s also worth noting that a rival, the Bain’s chemical telegraph (a “fax machine” of its day), was also on display, showcasing the rapid innovation and competition in this new field.

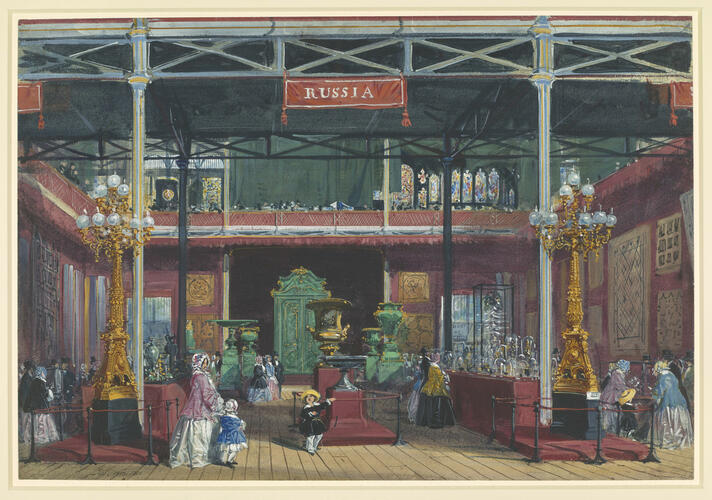

London 1851: The Great Exhibition. Russian Malachite Doors

A watercolour view of the Russian stand at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Signed and dated at bottom left: Joseph Nash 1851.

https://www.rct.uk/collection/919954/the-great-exhibition-russia

The Russian Malachite Doors (and the accompanying “Demidoff Malachite”) were one of the most opulent and awe-inspiring displays at the 1851 Great Exhibition.

While Britain and America showcased machines and mass production, the Russian exhibit was a dazzling display of imperial luxury and raw natural resources. The centerpiece of this was a collection of colossal objects made from brilliant green malachite, a semi-precious mineral.

Why They Were a “Wonder”

- Sheer Opulence: The exhibit was dominated by a set of 14-foot-high malachite doors, a gigantic malachite urn, and various other vases and furniture. In an exhibition filled with steel, iron, and steam, this explosion of rich color and polished stone was a breathtaking contrast.

- Visual Spectacle: The vibrant, swirling, deep green of the polished malachite was visually stunning. It drew huge crowds, who saw it as a treasure from a “barbaric” and fabulously wealthy empire.

- A “Sham” of Incredible Skill: The “wonder” was also in the craft. The doors and urns were not carved from solid malachite (which is impossible, as the mineral doesn’t form in such large blocks). They were a masterpiece of veneer. Russian artisans had painstakingly cut thousands of thin malachite slices and, using a “mosaic” technique, fitted them together so perfectly that the swirling patterns matched and the seams were invisible.

This technique, which was a state secret, was almost as impressive as the material itself—it represented an “industrial” process of its own, but one dedicated to pure luxury rather than mass-market utility. The exhibit was a powerful statement of the Russian Empire’s “otherness” and its almost limitless wealth.

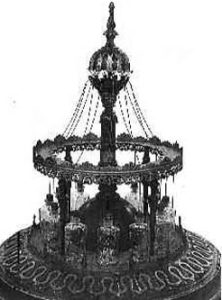

London 1851: The Great Exhibition. The Tempest Prognosticator

The Tempest Prognosticator

(Wiki Image Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=104944967)

This was one of the most eccentric and truly “Victorian” inventions at the Great Exhibition.

The Tempest Prognosticator, also known as the Leech Barometer, was a real, working weather forecasting machine that used live leeches to predict storms.

Dr. George Merryweather of Whitby, England, designed it.

How It Worked (The “Wonder”)

Dr. Merryweather was a firm believer in the folk wisdom that leeches become agitated and restless before a storm. His invention was an elaborate, ornate, and “scientific” way to harness this.

- The Setup: The device was a large, circular, metal stand with 12 small glass jars (bottles) placed around its edge. Each jar contained a single, live leech and a small amount of rainwater.

- The Trigger: Inside each jar, a small piece of whalebone was connected to a wire that ran up to a central bell.

- The “Prognostication”: When a leech sensed an atmospheric change (like a pressure drop), it would instinctively climb to the top of its jar. In doing so, it would push the whalebone trigger, which would ring the bell.

- The Signal: A single ring from one or two leeches might be a false alarm. But if many leeches became agitated and the bell rang frequently, Dr. Merryweather claimed it was a reliable sign of an approaching tempest (storm).

Significance at the Fair

The Tempest Prognosticator was a popular curiosity. It was a perfect blend of natural science, mechanical ingenuity, and showmanship that the Victorian public loved. It wasn’t a major industrial machine like the locomotive, but it was a “wonder” because it represented a serious, if bizarre, attempt to master nature and “prognosticate” (predict) the future.

Dr. Merryweather lobbied for the British government to install his invention at ports and harbors to warn ships of bad weather, but they ultimately favored the less accurate aneroid barometer.

🏛️ London 1851: The Great Exhibition, YouTube Video Links, Views

Here are several YouTube documentaries and visual histories that explore the 1851 Great Exhibition and its revolutionary building, the Crystal Palace.

-

Inside the Crystal Palace: the must-see exhibition of Victorian England

- Channel: Great Exhibition Road Festival

- Views: Over 1,200

- Description: A detailed lecture and visual tour from a V&A Museum curator, showing illustrations and photographs of the exhibition’s most popular and extraordinary works.

-

Virtual Tour of the Great Exhibition

- Channel: The Royal Parks

- Views: Over 31,900

- Description: This 28-minute documentary features a science presenter and a Royal Commission archivist who give a guided walk-through of a virtual 3D recreation of the Crystal Palace.

-

The Inventions Of The 1851 Great Exhibition (That Shook The World)

- Channel: Very Nearly Interesting

- Views: Over 11,700

- Description: This video uses rare photographs and sketches to offer a snapshot of the many inventions and innovations on display at the fair.

🏛️ London 1851: The Great Exhibition. Books

That’s a great request! The Great Exhibition of 1851 generated a massive number of publications, both official records and later historical analyses.

Here are some of the most significant books related to the event, categorized by type:

📜 Contemporary & Primary Source Books

These books were published during or immediately after the Exhibition and serve as primary records of the event.

- Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, 1851

- This is the definitive, multi-volume set authorized by the Royal Commission. It details every exhibit, classified by material and country, and includes numerous illustrations.

- A Guide to the Great Exhibition (1851)

- A smaller, single-volume handbook, such as the one published by G. Routledge & Co., was created for visitors, often featuring a map of the Crystal Palace and descriptions of key objects.

- The Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue: The Industry of All Nations, 1851

- A highly regarded, visually rich catalogue that focused on the decorative and fine arts exhibits, offering high-quality engravings.

- Lectures on the Results of the Great Exhibition of 1851 (Published 1852)

- A collection of speeches and essays by prominent figures on the social, artistic, and industrial impacts of the Exhibition.

🏛️ Modern Historical Studies

These scholarly works analyze the Exhibition’s cultural, political, and social significance from a modern perspective.

- The Great Exhibition of 1851: A Nation on Display by Jeffrey A. Auerbach (1999)

- A foundational modern text that explores how the Exhibition was conceived, experienced, and interpreted by different segments of British society, arguing that it served as a platform for national self-discussion.

- The World for a Shilling: How the Great Exhibition of 1851 Shaped a Nation by Michael Leapman (2001)

- A popular history that focuses on the human stories, logistical triumphs, and lasting influence of the event.

- Photography and the 1851 Great Exhibition by Anthony Hamber (2018)

- A specialized study detailing the crucial role the Exhibition played in the public launch and international acceptance of photography as a new art and industry.

🗼 Paris 1889: Exposition Universelle.

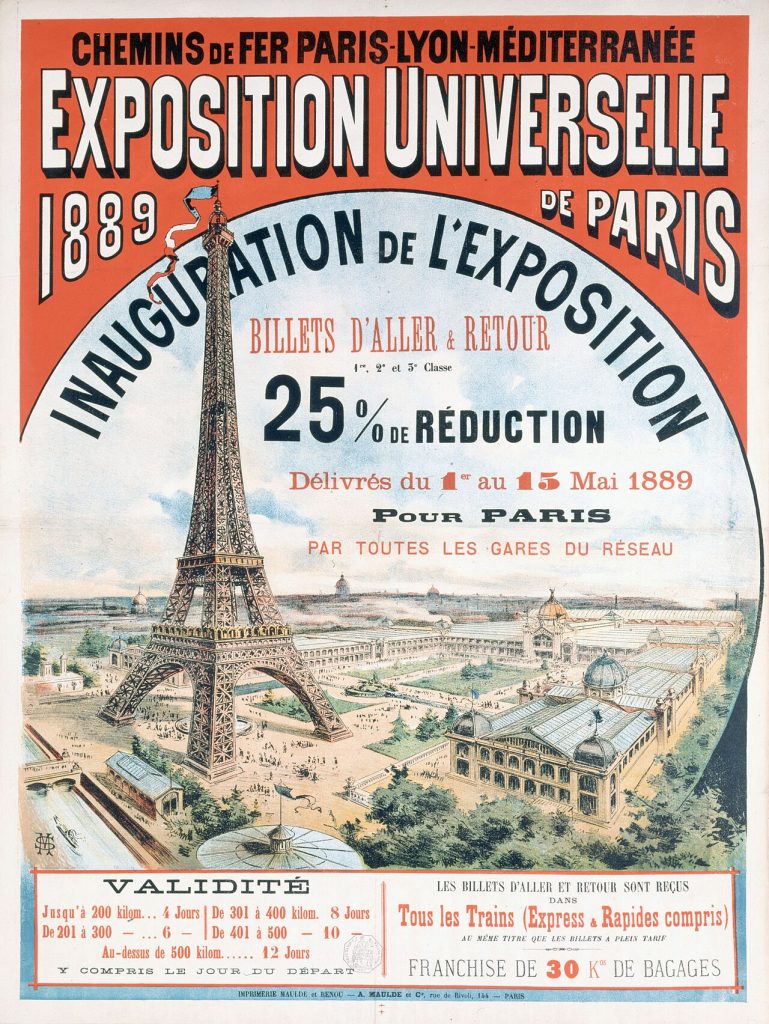

1889 Paris Poster

(Wiki Image By M.S. (monogramme), dessinateur Imprimerie A. Maulde et Cie, imprimeur Unknown author – Musée Carnavalet, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4231834)

🗼 Paris 1889: Exposition Universelle. Quotes

Here are some of the most famous and representative quotes from and about the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle.

The fair was completely dominated by its new, 300-meter iron tower, which sparked both intense admiration and profound disgust.

🗼 On the Eiffel Tower: The “Protest of the Artists”

Before the fair, a group of France’s most prominent cultural figures, led by Guy de Maupassant and Charles Gounod, published a famous protest letter in the newspaper Le Temps:

“We, writers, painters, sculptors, architects, and passionate devotees of the hitherto untouched beauty of Paris, protest with all our strength, with all our indignation in the name of slighted French taste…

…against the erection… of this useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower… To comprehend what we are arguing, one only needs to imagine for a moment a giddy, ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack, crushing under its barbaric bulk Notre Dame, the Tour Saint-Jacques, the Louvre, the Dome of les Invalides, the Arc de Triomphe, all of our humiliated monuments…”

🗼 Gustave Eiffel’s Defense

Gustave Eiffel, the engineer, defended his tower not as art, but as a monument to science and engineering.

“The Tower will be the tallest edifice ever raised by man. Will it not, therefore, be grandiose in its own way?

…Why should what is admirable in Egypt not be admirable and good in Paris? I seek a reply. I am, I must admit, jealous of my monument… It will be a symbol of the age of iron and the industry in which we live.”

🇺🇸 Thomas Edison’s Praise

The American inventor was a superstar at the fair. He visited the tower and, in the guestbook, wrote a glowing tribute to its creator:

“To M. Eiffel the Engineer, the brave builder of so gigantic and original a specimen of modern engineering, from one who has the greatest respect and admiration for all Engineers, including the Great Engineer, the Bon Dieu [Good God].

— Thomas A. Edison”

😮 A Visitor’s General Impression

A journalist for the San Francisco Chronicle captured the fair’s overwhelming, futuristic atmosphere:

“Night is the best time to see the Exposition. Then the full glory of the electric light, the full beauty of the illuminated fountains, the full weirdness of the shadow-casting tower, and the full gaiety of the streets of all nations are upon the visitor.”

🗣️ On Edison’s Phonograph

The phonograph was the other “must-see” wonder. A contemporary American visitor, Ida M. Tarbell, described the magical effect it had on the crowd:

“The first time I ever heard a phonograph was at the Paris Exposition of 1889… For the first time, I heard a machine which, after a man had talked or sung into it, would repeat what he had said or sung. It was a most amazing, uncanny, and, for a time, a not altogether pleasant experience. It seemed uncanny to hear this thing talk…”

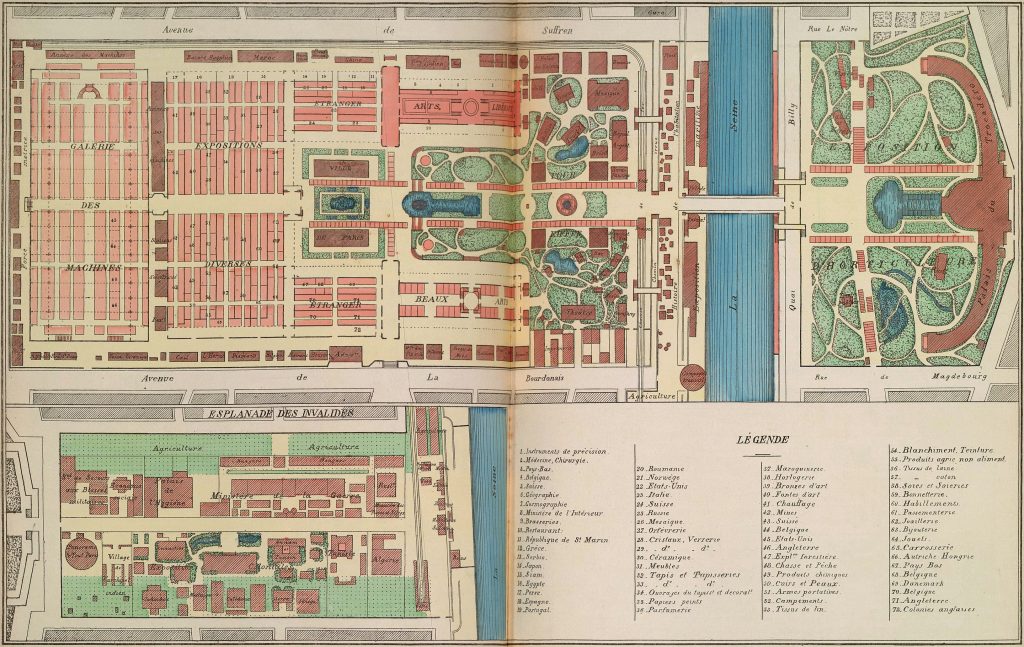

🗼 Paris 1889: Exposition Universelle. History

Plan of the Exposition Universelle of 1889

(Wiki Image By This image is available from the Brown University Library under the digital ID 1254153651293933., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24725417)

The 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle, or World’s Fair, was a massive international event held from May 6 to October 31, 1889. It was a spectacular showcase of industrial, scientific, and cultural achievements, designed to prove that France had recovered its power and prestige after its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and a period of economic recession.

🏛️ Purpose and Significance

The exposition’s primary purpose was to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution and the Storming of the Bastille. It was a bold political statement, intended to solidify the international standing of the French Third Republic. By creating a dazzling spectacle of progress, France showcased its industrial might, engineering genius, and the perceived success of its republican government. The fair was a tremendous success, attracting over 32 million visitors and turning a significant profit.

🗼 The Eiffel Tower

The most famous symbol of the fair was its monumental entrance arch: the Eiffel Tower.

- The “Iron Lady”: Designed by engineer Gustave Eiffel, the 300-meter (984-foot) tower was a marvel of wrought-iron engineering.

- A Controversial Star: At the time, it was the world’s tallest man-made structure. Its design was deeply controversial, prompting a group of prominent artists and writers to publish a letter protesting the “useless and monstrous” tower.

- Enduring Icon: Despite the protests, the tower was the fair’s star attraction, proving its engineering and commercial value. It was intended to be temporary, but was saved from being dismantled because it was so valuable as a radiotelegraph station.

⚙️ The Gallery of Machines

While the Eiffel Tower is more famous today, the Galerie des Machines (Gallery of Machines) was considered its architectural equal at the time.

- A Feat of Engineering: This enormous iron-and-glass pavilion was the largest single-span structure in the world, measuring 115 meters (377 feet) wide.

- The “Cathedral of Industry”: Its design, featuring massive three-hinged arches, created a vast, column-free interior.

- Showcase of Technology: Inside, it housed the fair’s industrial and technological exhibits, including Thomas Edison’s new phonographs, demonstrating the power of the new industrial age.

🌍 Other Major Attractions

- Thomas Edison’s Pavilion: The American inventor was a superstar at the fair. His pavilion, which showcased his newly improved phonograph, was a massive draw, allowing visitors to listen to recorded music through listening tubes.

- Illuminated Fountains: The central fountain used new, colored electric lights to create a magical, synchronized display of water and light, symbolizing the new “Age of Electricity.”

- “Human Zoos”: A popular but now deeply controversial part of the fair was the “human zoo” exhibits. The “Rue du Caire” (Cairo Street) was a full-scale reproduction of a street in Cairo, populated by Egyptian artisans, performers, and animals, and presented an exoticized, colonial view of other cultures.

- Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show: Performing near the fairgrounds, Buffalo Bill Cody and his show, featuring the sharpshooter Annie Oakley, were a massive entertainment hit, introducing a romanticized vision of the American West to Europe.

This video provides a brief historical overview of the 1889 Exposition Universelle. A Look Back at the 1889 Paris Exhibition

🗼 Paris 1889: Exposition Universelle. Eight Wondrous Exhibition

The 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris was a celebration of the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution and a spectacular showcase of the “Age of Steel and Electricity.”

Its greatest wonder was the entrance arch that towered over the fairgrounds: the Eiffel Tower. At 300 meters (984 feet), it was the tallest man-made structure in the world, a breathtaking feat of engineering that became the enduring symbol of Paris.

Here are eight other wondrous exhibits and attractions from the 1889 Fair.

8 Wondrous Exhibits of the 1889 Exposition Universelle

| Exhibit | Origin | Significance & “Wonder” |

| 1. The Gallery of Machines | France | This was the other great architectural marvel of the fair. A massive iron-and-glass pavilion, it featured the world’s longest column-free arch (377 feet). It housed the fair’s industrial and machinery exhibits, creating a vast, cathedral-like space for technological wonders. |

| 2. Edison’s Phonograph Pavilion | United States | Thomas Edison was a superstar at the fair. His pavilion showcased his new phonograph, a “talking machine” that was pure magic to the public. Visitors lined up for hours to listen to recorded music and speech through individual listening tubes. |

| 3. The “Rue du Caire” (Cairo Street) | Egypt (Colonial Exhibit) | This was one of the most popular and controversial exhibits. It was an elaborate, full-scale reproduction of a street in Cairo, complete with shops, cafes, belly dancers, and 250 donkeys for visitors to ride. It was a key part of the “human zoo” element, presenting an exoticized version of colonial life. |

| 4. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show | United States | Though technically performing adjacent to the fair, Buffalo Bill and his show (including Annie Oakley) were the runaway entertainment hit. They performed for massive crowds, introducing Europeans to a romanticized, thrilling vision of the American frontier. |

| 5. The Illuminated Fountains | France | The central fountain was the centerpiece of the nightly spectacles. Using new technology, it was illuminated from within by colored electric lights, creating a magical, changing display of water and light that visitors had never seen before. It was a symbol of the new “City of Light.” |

| 6. The Benz Patent-Motorwagen | Germany | Tucked inside the Gallery of Machines was a revolutionary invention: Karl Benz’s three-wheeled automobile. While it didn’t draw the same crowds as the tower, this was the first time the public was introduced to a commercially available gasoline-powered car. |

| 7. The “History of Habitation” | France | Designed by the architect of the Eiffel Tower’s base, this was a popular and peculiar exhibit. It was a large park featuring 44 full-scale, “authentic” replicas of human houses throughout history, from a caveman’s grotto to an Aztec temple and a Renaissance home. |

| 8. The Internal Decauville Railway | France | The fairgrounds were so massive that a special miniature railway was built to transport visitors. This 60cm gauge train was a wonder in itself, carrying over 6 million people during the exhibition and proving the viability of such light railways for public transport. |

Paris 1889: Exposition Universelle. The Gallery of Machines

Interior of the Galerie des machines (1889), built by Victor Contamin and Ferdinand Dutert.

(Wiki Image By Library of Congress/original author unknown – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph. 3g13526.This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=303525)

The Galerie des Machines (Gallery of Machines) was the other primary architectural marvel of the 1889 Exposition Universelle. While the Eiffel Tower was the “wonder” of height, the Gallery of Machines was the “wonder” of space.

It was a colossal iron-and-glass pavilion designed by the architect Ferdinand Dutert and the engineer Victor Contamin to serve as the main industrial exhibit hall.

Why It Was a “Wonder”

- World’s Longest Interior Span: The building’s main hall was 115 meters (377 feet) wide and 420 meters (1,378 feet) long. Its “wonder” was its roof, which was supported by massive, three-hinged trussed arches. This design created the largest, column-free interior space in the world, a breathtaking “cathedral of industry.”

- A Showcase of Industrial Power: The vast hall was filled with the most advanced industrial technology of the day. It was a noisy, dynamic spectacle of machines in motion, including steam engines, dynamos, and manufacturing equipment, all demonstrating the power of the new industrial age.

- Key Inventions: It was here that Thomas Edison showcased his phonograph to astonished crowds. It was also where Karl Benz displayed his Patent-Motorwagen, one of the first commercially available automobiles, introducing the public to the future of transportation.

- The Internal “Ride”: An overhead rolling crane (pont roulant), designed to move heavy machinery, was itself a popular attraction. Visitors could ride on its platform as it traveled the length of the hall, giving them a spectacular elevated view of the exhibits below.

While the Eiffel Tower became the permanent icon, many contemporary critics considered the Gallery of Machines to be the true architectural masterpiece of the Base of the 1889 Fair. It was demolished in 1909.

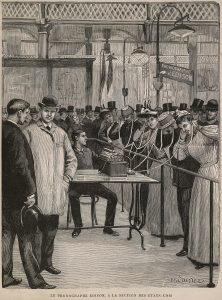

Paris 1889: Exposition Universelle. Edison’s Phonograph Pavilion

The Edison phonograph was demonstrated at the exposition.

(Wiki Image By Paul Uestel – This image is available from the Brown University Library under the digital ID 1254148461578125., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24702628)

Thomas Edison’s pavilion was one of the absolute superstars of the 1889 Exposition. The main attraction was his recently improved phonograph, a machine that seemed like pure magic to the public.

It was a “talking machine” that could record and play back sound. This was a revolutionary concept, and the exhibit was designed for a massive, personal experience.

Why It Was a “Wonder”

- A Magical Technology: For the first time, people could hear a machine reproduce music and human speech. Edison himself was treated like a wizard, and the phonograph was his greatest marvel.

- The Interactive Experience: The pavilion featured dozens of phonographs. Visitors would wait in long lines for their turn to put a set of individual listening tubes (like a stethoscope) to their ears.

- A Global Showcase: They would listen with astonishment to pre-recorded music, famous speeches, or greetings in different languages. This individual’s personal experience of hearing recorded sound for the first time made it one of the most memorable and popular attractions at the entire fair.

Edison’s exhibit cemented his status as the world’s most famous inventor and was a powerful symbol of American technological ingenuity.

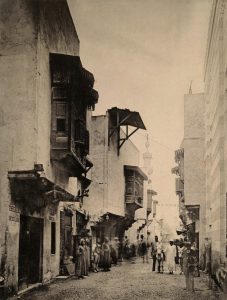

Paris 1889: Exposition Universelle. The “Rue du Caire” (Cairo Street)

The “Cairo Street”

(Wiki Image By This image is available from the Brown University Library under the digital ID 1254162040163050., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24742615)

The “Rue du Caire” (Cairo Street) was one of the most popular and commercially successful attractions at the 1889 Exposition Universelle.

It was an early and elaborate example of an immersive themed environment. It was not just a display of objects; it was a full-scale, architecturally accurate reproduction of a street in medieval Cairo, designed to transport visitors to an “exotic” new world.

Why It Was a “Wonder”

- Immersive Authenticity: The exhibit was a winding, realistic street lined with shops, cafes, mosques, and houses, all built in a traditional Mamluk architectural style.

- “Human Zoo” Element: The “wonder” (and controversy) was that the street was populated. It featured around 200 people (artisans, merchants, performers) and animals (including 250 donkeys for rides) brought directly from Cairo. Visitors could watch artisans work, buy goods, and interact with people presented as “authentic” inhabitants.

- Introduction of Belly Dancing: The “Rue du Caire” is famously credited with introducing belly dancing (danse du ventre) to the Western public. The performances, seen as scandalous and sensual by Victorian standards, were a massive sensation and a primary reason for the exhibit’s popularity.

While it was a “wonder” of entertainment and immersion for its time, it is also a key example of the 19th-century “human zoo” phenomenon, where colonial subjects and their cultures were put on display as exotic attractions.

Paris 1889: Exposition Universelle. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show

Buffalo Bill Cody, painted in 1889 by Rosa Bonheur

(Wiki Image By Rosa Bonheur – Whitney Gallery of Western Art Collection, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19106540)

While Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show was not an official exhibit within the 1889 Exposition Universelle, it was set up on a massive 3-acre lot just outside the fairgrounds. It was the runaway entertainment sensation of the event, and for millions of visitors, it was the single most memorable part of their trip.

Why It Was a “Wonder”

- A Spectacle of the “Wild” Frontier: The show was a massive theatrical production, a “living” re-enactment of the American West. It wasn’t a circus; it was presented as a “historical” demonstration of life on the frontier.

- Global Superstars: It starred William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody himself, an international celebrity, and the legendary sharpshooter Annie Oakley. Oakley became the talk of Paris, amazing crowds by shooting targets while looking in a mirror or hitting a playing card’s edge from 30 paces.

- Massive Scale: This was no small show. It included:

- Over 100 “cowboys” and “vaqueros.”

- Around 100 Native American performers (including Lakota Sioux men and women).

- A herd of buffalo, elk, and wild horses.

- Key “Acts”: The show’s “wonders” were its re-enactments, which included a Pony Express mail-run simulation, a stagecoach being attacked, and spectacular marksmanship from Oakley.

Significance at the Fair

The show’s success was profound. It presented a powerful, romanticized, and thrilling vision of the American frontier that captivated Europe. For many, this show was the American exhibit, eclipsing the official U.S. displays of technology. It cemented the “cowboy” and the “Wild West” as defining parts of American identity in the global imagination.

Paris 1889: Exposition Universelle. The Illuminated Fountains

View of the Eiffel Tower from the Trocadéro Palace. The tower was intended to be a temporary structure serving as an entrance to the exhibit. The buildings represented behind the tower on this engraving are the main galleries of the exhibit (such as the Grande galerie des machines). They were destroyed at the beginning of the twentieth century.

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – This image is available from the Brown University Library under the digital ID 125414492496875., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php.curid=24356276)

The Illuminated Fountains were one of the most magical and popular nightly attractions of the 1889 Exposition Universelle. They were a centerpiece of the fairgrounds, located on the Champ de Mars, directly between the Eiffel Tower and the Gallery of Machines.

The main display, known as the “Fontaine Monumentale,” was designed by Eugène Vicaire.

Why It Was a “Wonder”

- A Symphony of Light and Water: The “wonder” was the brand-new technology. For the first time on a massive public scale, the fountains were illuminated from within by powerful, high-intensity electric lights.

- “Magic” Color Changes: The real spectacle was the color. The white light from the arc lamps was shone through a revolving series of colored glass filters (red, green, and blue). This allowed operators to “paint” the water in real time, making the water jets change from white to red to blue in a dazzling, pre-choreographed display.

- The “City of Light” Made Real: In an era when electric light was still a novelty, seeing it used so artfully to create a massive, colorful, and dynamic spectacle was pure magic to the visitors. It was a perfect symbol of the fair’s themes of electricity, modernity, and Paris as the “City of Light.”

The illuminated fountain shows were held every night, and the central esplanade would be packed with thousands of visitors who came to watch the “magic” display, which was often timed to music.

Paris 1889: Exposition Universelle. The Benz Patent-Motorwagen

The Benz Patent-Motorwagen Nr. 3 of 1888, used by Bertha Benz for the first long-distance journey by automobile (106 km (66 mi) long)

(Wiki Image by Unknown author – Benz, Carl Friedrich: Lebensfahrt eines deutschen Erfinders. Die Erfindung des Automobils, Erinnerungen eines Achtzigjährigen. Leipzig 1936, S. 155-156. zeno.org, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3180514)

The Benz Patent-Motorwagen (Model III) was a genuinely revolutionary, though somewhat overlooked, exhibit at the 1889 Paris Exposition.

It was a three-wheeled vehicle built by the German inventor Karl Benz. Its “wonder” was not in its size or beauty, but in its revolutionary technology: it was the first gasoline-powered automobile to be commercially available.

Why It Was a “Wonder”

- A “Horseless Carriage”: The vehicle was powered by a small, rear-mounted, single-cylinder internal combustion engine. To a public used to horses, steam, and electricity, this personal, self-propelled “horseless carriage” was a fascinating and bizarre novelty.

- Birth of an Industry: While the fair was dominated by the “Age of Steel” (the Eiffel Tower), this small machine, tucked away in the German section of the Gallery of Machines, represented the dawn of a new era. Benz was not just showing a prototype; he was there to sell his invention and find French business partners.

- Proven Technology: This was the same model that Karl’s wife, Bertha Benz, had famously driven on the world’s first-ever long-distance road trip (106 km) just a year earlier, proving its viability.

While the Patent-Motorwagen didn’t draw the same massive crowds as the Eiffel Tower or Edison’s phonograph, it was a “wonder” in the truest sense: a glimpse of a future that would completely reshape the world.

Paris 1889: Exposition Universelle. The “History of Habitation”

The Roman House and the Gallo-Roman House, by Charles Garnier

(Wiki Image By Fondo Antiguo de la Biblioteca de la Universidad de Sevilla from Sevilla, España – 537049, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51646634)

The “History of Habitation” (L’Histoire de l’Habitation) was one of the most popular and scholarly attractions at the 1889 Exposition. It was an “open-air museum” designed by Charles Garnier, the celebrated architect of the Paris Opera.

This was a serious attempt to create a “scientific” and educational exhibit that was also highly entertaining.

Why It Was a “Wonder”

- A “Walk Through Time”: The exhibit was a park-like area on the Champ de Mars containing 44 full-scale, “authentic” replicas of human dwellings throughout history. Visitors could literally walk from a “prehistoric” cave and a Stone Age hut to an Egyptian villa, an Aztec temple, a Roman house, a medieval manor, and a Renaissance pavilion.

- Designed by a Superstar Architect: The fact that Charles Garnier—the master of the opulent, neo-baroque Opera House—designed it gave the exhibit immense prestige. It was a “wonder” to see such a high-profile artist applying his talents to recreating “primitive” huts and “barbaric” homes.

- Educational Entertainment: It perfectly captured the 19th-century “armchair tourism” and obsession with anthropology. It was a “human zoo” of architecture, allowing visitors to feel as though they were “time-traveling” and understanding the evolution of mankind in a single, pleasant stroll.

The exhibit was an enormous popular success, blending a high-minded scholarly purpose with the novel, picturesque, and “exotic” experience that fairgoers loved.

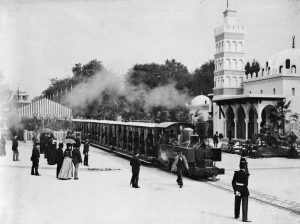

Paris 1889: Exposition Universelle. The Internal Decauville Railway

Exposition Universelle (1889) Decuville railway

(Wiki Image By Unknown author – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.3c01100. This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3602830)

The Decauville Railway was the internal, narrow-gauge train system that served as the primary mode of transportation inside the massive 1889 Exposition Universelle.

It was not just a utility; it was an attraction in its own right and a “wonder” of modern, light-rail technology.

Why It Was a “Wonder”

- A “Miniature” Mass-Transit System: The fairgrounds were enormous (237 acres). The Decauville railway was a complete, functioning transit network, with 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) of track and multiple stations, designed to move millions of people. The “wonder” was a miniature passenger railway.

- Novel, Flexible Technology: It was a 60cm (2-foot) narrow-gauge line using the “Decauville” system of prefabricated, portable, and easily laid track sections. This was a new, light, and flexible alternative to heavy, permanent rail.

- An Attraction in Itself: The open-sided, “toast-rack” passenger cars were a ride, not just a commute. The line ran along the main avenues, offering spectacular views, and even passed through the Gallery of Machines and the Agricultural pavilion, making the journey part of the exhibition experience.

- Immense Popularity and Success: The railway was a massive hit. It carried over 6.5 million passengers during the fair’s six months, proving its efficiency and popularity. It was a “wonder” because it successfully applied industrial rail technology to public mass transit.

🗼 Paris 1889: Exposition Universelle. YouTube Video Links Views

Here are several YouTube videos that provide historical overviews, documentaries, and visual tours of the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle.

-

-

- Channel: Busy Baçi

- Views: Over 59,000

- Description: A concise (under 2 minutes) visual tour using restored photographs and 3D models to show the scale of the fairgrounds, including the Gallery of Machines and the Eiffel Tower.

-

-

-

- Channel: Best Documentary

- Views: Over 4.1 million

- Description: This full-length documentary focuses on the construction and history of the Eiffel Tower, the centerpiece of the 1889 Exposition. It details the engineering challenges and the controversy surrounding its creation.

-

Building the Eiffel Tower | Full Documentary | NOVA | PBS (Note: The search result snippet links to a photo montage, but the title “Building the Eiffel Tower” from NOVA PBS, referenced in the snippet, is a high-quality documentary.)

- Channel: NOVA PBS Official (and various re-uploads)

- Views: Over 1.2 million (on one version)

- Description: This documentary explores the engineering and construction of the Eiffel Tower, placing it firmly in the context of the 1889 World’s Fair.

-

-

- Channel: (Channel name not in snippet)

- Views: Not specified, but part of a high-traffic topic.

- Description: This video serves as a detailed guide to the Eiffel Tower, explaining its history and construction, specifically focusing on its role in the World’s Fair.

🗼 Paris 1889: Exposition Universelle. Books

Here are the most essential and well-regarded books on the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle, ranging from gripping narrative histories to comprehensive illustrated guides.

1. The Definitive Narrative History

“Eiffel’s Tower: The Thrilling Story Behind Paris’s Beloved Monument and the Extraordinary World’s Fair That Introduced It”

- By: Jill Jonnes

- This is widely considered the best modern, narrative history of the fair in English. While the Eiffel Tower is the central character, the book uses it as a lens to tell the full story of the Exposition. It masterfully weaves together the technological marvels (Edison’s phonograph, the Gallery of Machines) with the spectacular entertainment (Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show) and the intense cultural and artistic debates of the era.

2. The Best Illustrated (Visual) History

“1889 Paris World’s Fair: The Exposition Universelle in Illustrations” (Volumes 1 & 2)

- By: Mark Bussler

- If you want to see the fair as its visitors did, this is the book to get. It’s a meticulously compiled visual record, featuring hundreds of digitally restored engravings, illustrations, and maps from contemporary 1889 publications. It’s the perfect companion to a narrative history, showing you the scale of the fairgrounds, the details of the pavilions, and the tower’s construction.

3. The Best Book for Cultural Context

“Dawn of the Belle Epoque: The Paris of Monet, Zola, Bernhardt, Eiffel, Debussy, Clemenceau, and Their Friends”

- By: Mary McAuliffe

- This book is not about the World’s Fair, but it’s the perfect book to understand the world that created it. It’s a “year-by-year” history of Paris from 1871 to 1900, placing the 1889 Exposition in its proper context, surrounded by the art of the Impressionists, the literature of Émile Zola, and the political scandals of the new French Republic.

4. Original (Primary Source) Exhibition Catalog

“1889: La Tour Eiffel et l’Exposition universelle”

- By: Musée d’Orsay

- This is the official catalog from the 1989 centennial exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay. It is a French-language book but is an invaluable, scholarly resource filled with original photographs, architectural plans, and essays on the fair’s art, design, and cultural impact, including in-depth looks at the colonial exhibits and the Gallery of Machines.

🎡 Chicago 1893: World’s Columbian Exposition.

Looking West From Peristyle, Court of Honor and Grand Basin of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (Chicago, Illinois)

(Wiki Image By C. D. Arnold (1844-1927); H. D. Higinbotham – The Project Gutenberg EBook of Official Views Of The World’s Columbian Exposition, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50469469)

🎡 Chicago 1893: World’s Columbian Exposition. Quotes

Here are some of the most famous and representative quotes from and about the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, capturing its sense of awe, its cultural impact, and its complex legacy.

🏛️ The Fair’s Ambitious Vision

This quote, though perhaps spoken by architect Daniel Burnham after the fair, has become its unofficial motto and perfectly captures the audacious spirit of its creators:

“Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized. Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone will be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing insistency.”

A contemporary journalist, Walter Besant, expressed the utopian, almost dream-like quality of the “White City”:

“This is not a City for a single summer: it is a City which should belong to the world… It is the dream of a poet, a vision of some celestial city.”

😮 The Shock of the New: Technology & Culture

The fair was a turning point for many visitors, who saw a new world of technology and ideas opening before them.

The historian Henry Adams wrote of the intellectual and technological shock he felt at the fair, contrasting the classical “White City” with the powerful, new machinery:

“Chicago was the first expression of American thought as a unity; one must start there… One sat down to ponder on the steps of Richard Hunt’s Administration Building and gazed at the Court of Honor… Chicago was colossal.”

The fair’s most popular attractions were the Ferris Wheel and the chaotic Midway. A popular ditty of the day, famously referenced by a visitor, showed how the exotic Midway overshadowed the high-minded exhibits:

“After the fair, I’m goin’ back to the farm… For I’ve seen the streets of Cairo, I’ve seen the big Ferris wheel, and I’ve seen the Trocadero, but I’ve not seen the Art quadrille. Oh, I’m sad and sick and sorry that I’ve got to go to plow, But I’m goin’ to tell the people that I’ve seen the Midway anyhow!”

✨ A Pivotal Moment for America

The fair introduced many Americans to new foods, products, and ideas, as summed up by the historian Reid Badger:

“For the visitor, the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 was a short course in the history of civilization and a glance at the Utopian future, all for 50 cents. Visitors… were introduced to the Ferris wheel, the zipper, Cracker Jack, shredded wheat, juicy fruit gum, and… electric lights.”

🌍 A New Global Stage

The Parliament of the World’s Religions at the fair was a landmark event. The Hindu monk Swami Vivekananda made a powerful, star-making debut in the West with his opening words:

“Sisters and Brothers of America… I am proud to belong to a religion that has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance. We believe not only in universal toleration, but we accept all religions as true.”

📖 The Modern Perspective: The Devil in the White City

Erik Larson’s 2003 bestselling book captured the fair’s magic and darkness for a new generation. He described the profound effect of the fair’s electric illumination:

“When visitors came to the Court of Honor… they saw a dream of perfect beauty, a city of white palaces… At night, the transformation was even more compelling. The fair alone, among all the places in the world, was completely illuminated by electricity. It was a wonderland.”

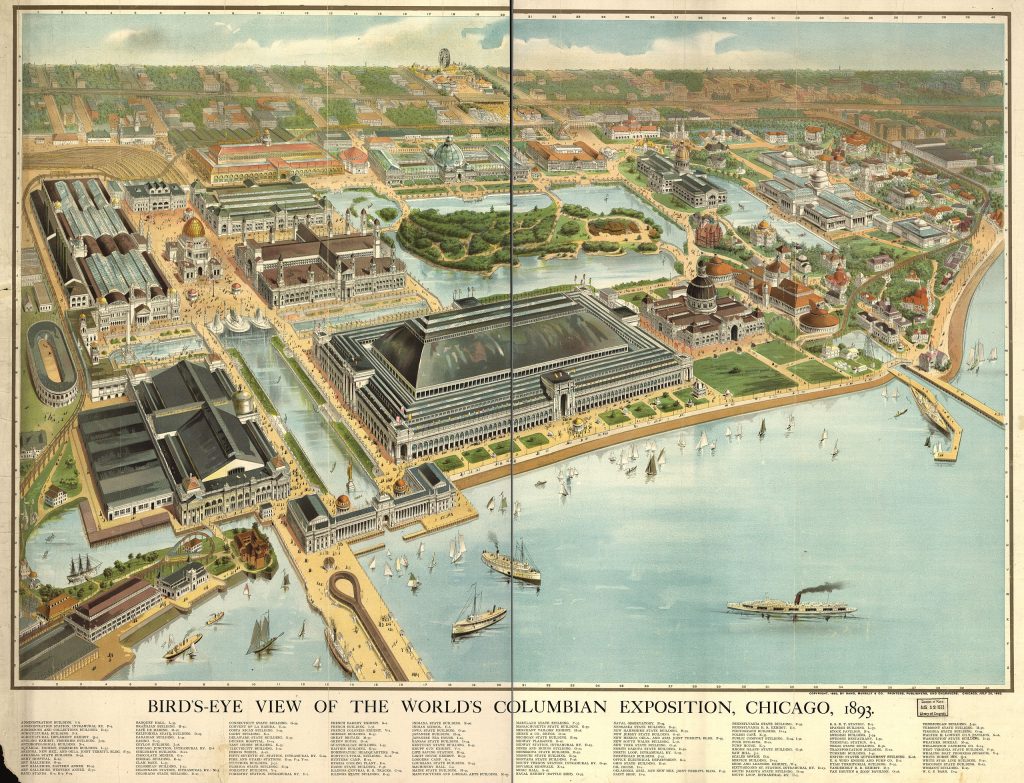

🎡 Chicago 1893: World’s Columbian Exposition. History

Bird’s Eye View, 1893

(Wiki Image By Rand McNally and Company – Library of Congress, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50474238)

Here is the history of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

🏛️ The “White City”

The World’s Columbian Exposition was a massive and profoundly influential World’s Fair held in Chicago in 1893. While officially celebrating the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the New World (it opened a year late), its real purpose was to prove that Chicago—and by extension, the United States—had “arrived” as a cultural and industrial equal to the great cities of Europe, especially its direct rival, the 1889 Paris Fair.

🏙️ The Vision: A Utopian City

Directed by architect Daniel Burnham with a landscape designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, the fair’s main campus was a stunning spectacle known as the “White City.”

- Architecture: Burnham brought together the nation’s top architects (like Louis Sullivan) to design a unified, harmonious, and monumental campus. They chose a neoclassical (or “Beaux-Arts”) style, and nearly all the buildings were covered in white stucco, giving the fairgrounds a gleaming, dream-like appearance.

- The “City Beautiful” Movement: This vision of a clean, grand, and orderly city was so influential that it launched the “City Beautiful” movement, which would shape American city planning and public architecture for decades.

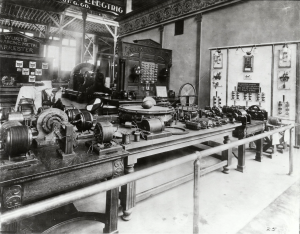

⚡ The “War of the Currents”

The fair was the first all-electric fair, and it became the main battleground for the “War of the Currents.”

- Thomas Edison (DC): He bid to illuminate the fair with his direct current (DC) system.

- Westinghouse & Tesla (AC): George Westinghouse, using Nikola Tesla’s alternating current (AC) patents, dramatically underbid Edison.

- The Result: Westinghouse won the contract. The “White City” became the “City of Light,” the largest demonstration of electric illumination the world had ever seen. Its dazzling success proved the superiority of AC for large-scale power distribution, effectively ending the “war.”

🎡 The Midway Plaisance & The Ferris Wheel

In contrast to the high-minded, classical “White City,” a mile-long strip called the Midway Plaisance served as the fair’s entertainment and amusement zone.

- The Ferris Wheel: This was the star of the Midway and America’s answer to the Eiffel Tower. Designed by George W. G. Ferris, it was a 264-foot-tall rotating steel wheel, a mechanical marvel that carried over 2,000 passengers at a time.

- “Exotic” Exhibits: The Midway featured “human zoo” exhibits, including the hugely popular “Street in Cairo,” which famously introduced belly dancing to a shocked and fascinated American public.

📖 Lasting Impact and Innovations

The fair was a massive success, attracting 27 million visitors. Its influence on American culture was profound:

- New Products: It introduced the public to Cracker Jack, Juicy Fruit gum, Shredded Wheat, and the zipper.

- Cultural Milestones: The Pledge of Allegiance was written for the event. The Parliament of the World’s Religions, held in conjunction with the fair, was the first formal gathering of Eastern and Western spiritual leaders, famously introducing Swami Vivekananda and Hinduism to America.

🔥 A Darker Side and Tragic End

- Exclusion: The fair was criticized by activists like Ida B. Wells for its racist and exclusionary portrayal of African Americans.

- H. H. Holmes: The fair’s chaotic atmosphere was famously exploited by America’s first serial killer, H. H. Holmes, who built a “Murder Castle” hotel to lure and kill visitors.

- The Fire: The “White City” was a temporary dream. Its buildings were not made of marble but of a temporary material called “staff.” Shortly after the fair closed, a massive fire swept through Jackson Park, destroying most of the “White City” and leaving its “heavenly” vision in blackened ruins.

This video from PBS’s American Experience provides an excellent overview of the fair and its cultural impact. The World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893

🎡 Chicago 1893: World’s Columbian Exposition. Frederick Law Olmsted

Olmsted in 1893; engraving after a photograph.

(Wiki Image By James Notman, Boston; engraving of image later published in Century Magazine (source) – The World’s Work, 1903: https://archive.org/stream/worldswork06gard#page/3938/mode/2up, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26824311)