Polybius in Royal Blue, Livy in Brundt Orange, and Plutarch in Green.

Introduction

In a speech, Robert Garland, Ph.D. Colgate University (Experiencing Great Events of the Ancient and Medieval Worlds) provides a gripping account of what happened after the Battle of Cannae:

“It’s August second, 218 BCE, and a horseman, bearing news in Rome of the most disastrous military failures the city had suffered in its 500-year history. We don’t know the exact number of casualties, and estimates vary between 50,000 and 70,000 men, but it has been nothing less than a blood bath. It includes 80 senators and a greater number of men of the equestrian rank, all extremely wealthy, and 24 out of 48 tribunes. The battle occurred at a town called Cannae in Apulia, 300 miles southeast of Rome.

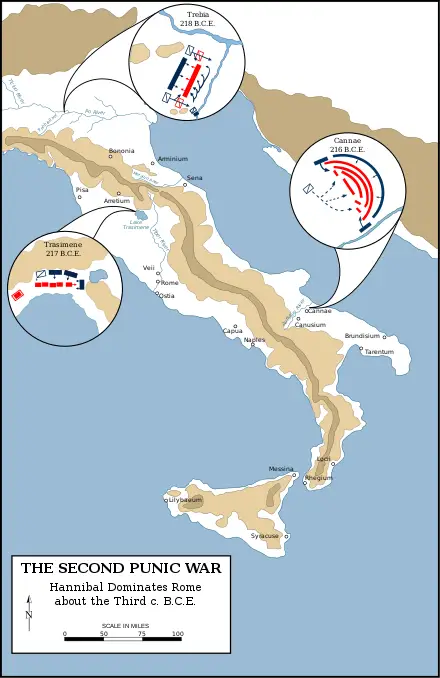

Trebia (218 BC) and Trasimene (217 BC) to the Northwest of Rome, Cannae (216 BC) to the Southeast (Wikipedia Image)

The initial report has been that there are no survivors. Later, that report will prove to be false. Victorious Carthaginian General Hannibal, from afar, offered to ransom 8,000 prisoners as long as the Romans agreed to the peace terms. Hannibal sent ten highly distinguished Roman prisoners to make a personal appeal to increase the pressure on the Roman Senate. Under solemn oath, the prisoners return to Cannae after making the presentation. The crisis for the Senate is whether to hold firm or make peace with the enemy and save the lives of prisoners from death or slavery.

This is the most critical decision the Roman Senate has ever made. None at this point knows how to identify the dead, but there is hardly a family that does not have a member who fought at Cannae and might be a prisoner. Thousands of Romans are gathered outside the senate house, knowing their fate will be determined if one is caught up in Hannibal’s prisoner camp.”

The Romans hated the nightmarish Hannibal. Roman mothers would frighten their naughty children for centuries with “Hannibal ad portas” (Hannibal at the Gates).

Polybius, a Greek historian of the 2nd century BC, provides one of the most comprehensive and insightful accounts of Hannibal Barca, the Carthaginian general renowned for his audacious crossing of the Alps and his military campaigns against Rome during the Second Punic War. Polybius, who had access to primary sources and even visited the sites of Hannibal’s battles, admired the Carthaginians’ strategic brilliance, tactical adaptability, and unwavering determination. He meticulously chronicled Hannibal’s daring exploits, including the stunning victory at Cannae and the prolonged occupation of Italy, while also analyzing his flaws and the factors that ultimately led to his downfall. Polybius’s balanced and objective portrayal of Hannibal offers valuable insights into the character and motivations of one of history’s most remarkable military leaders.

“Of all that befell the Romans and Carthaginians, good or bad, the cause was one man and one mind — Hannibal…So great and wonderful is the influence of a Man and a mind duly fitted by the original constitution for any undertaking within reach of human powers.”

Plutarch, the Greek biographer and moralist of the 1st century AD, presents Hannibal Barca as a figure of immense courage, strategic brilliance, and unwavering resolve, yet marred by cruelty and a thirst for vengeance. In his Parallel Lives, Plutarch juxtaposes Hannibal with the Roman general Scipio Africanus, highlighting their contrasting leadership styles and ultimate fates. Plutarch admires Hannibal’s audacious crossing of the Alps and his stunning victories against Rome, particularly at Cannae. However, he also criticizes Hannibal’s harsh treatment of conquered cities and inability to adapt to changing circumstances, ultimately leading to his defeat and exile. Plutarch’s portrayal of Hannibal is complex and nuanced, recognizing his military genius while acknowledging his flaws and the tragic consequences of his ambition.

It says in Plutarch’s Lives, Fabius:

“But Hannibal now burst into Italy and was at first victorious in battle at the river Trebia. Then he marched through Tuscany, ravaging the country, and smote Rome with dire consternation and fear. Signs and portents occurred, some familiar to the Romans, like peals of thunder, others wholly strange and quite extraordinary. For instance, it was said that shields sweated blood, that ears of corn were cut at Antium with blood upon them, that blazing, fiery stones fell from on high, and that the people of Falerii saw the heavens open and many tablets fall down and scatter themselves abroad, and that on one of these was written in letters plain to see, ‘Mars now brandisheth his weapons (Mars Nunc telum vibrans).’”

Livy, the renowned Roman historian of the 1st century BC, paints a vivid and dramatic portrait of Hannibal Barca, the Carthaginian general who became Rome’s most formidable adversary during the Second Punic War. In Livy’s narrative, Hannibal emerges as a complex and enigmatic figure, a brilliant strategist and a ruthless warrior driven by an insatiable thirst for vengeance against Rome. Livy emphasizes Hannibal’s audacity, cunning, and unwavering determination, portraying him as a near-mythical foe who pushed Rome to the brink of destruction. While acknowledging Hannibal’s military genius, Livy also underscores his cruelty, treachery, and, ultimately, his tragic downfall. This portrayal, though colored by Roman patriotism, has shaped our understanding of Hannibal for centuries, solidifying his place as one of history’s most captivating and controversial figures.

“Many a man often saw him wrapped in his military cloak, lying on the ground amid the sentries and pickets. His dress was not superior to his comrades, but his accouterments and horses were conspicuously splendid. Among the cavalry or the infantry, he was by far the first soldier, the first in battle, the last to leave it when once begun.

These great virtues in the Man are equaled by monstrous vices: inhuman cruelty, a worse than Punic perfidy. Absolutely false and irreligious, he had no fear of God, no regard for an oath, no scruples.”

Unfortunately, no Carthaginian tale of Hannibal exists. In the Third Punic War in 156 BC, the Romans stormed Carthage, sold the survivors into slavery or killed them, razed the city, and plowed the site with salt, so no evidence of Carthage’s historical existence remained.

Could this have been prevented? Could Carthage have ultimately defeated Rome in the Punic Wars?

Given the gravity of the defeat at Cannae, Hannibal was sure the Romans would accept his proposal to return 8,000 high-ranking prisoners for gold and territorial concessions. Yet, as a great leader, Hannibal considered alternatives to what he would do if the Romans rebuffed his offer.

Rome and its allies, throughout Italy and the provinces, had “700 thousand foot soldiers and 70,000 horses” (according to Polybius). The entire Carthaginian Empire had only about 250,000 troops in total. Rome’s total is more than three times that of the Carthaginian Punic Empire. [One comparison done by Gabriel (Scipio Africanus: Rome’s Greatest General by Richard A. Gabriel) suggests that the initial manpower pool enjoyed by Rome and her allies was somewhat greater than five times the number of Carthaginian soldiers. I like a number higher because of the Punic mercenaries.]

Hannibal needs more troops. His initial plan is to split Rome from its allies by battle, pillage, and negotiation. After two years, he still needed to be successful. This is mainly due to Roman propaganda. Hannibal is painted barbarically. He could not secure additional support despite the initial limited success of his strategy. Maybe victory at Cannae will cause some supporters to veer to Hannibal’s side?

However, Hannibal needs Rome to capitulate quickly. If they can stall, they can bring many more troops to bear. He cannot depend on his victory to get more allies. He must develop an alternate strategy.

Hannibal rejected laying siege to Rome. Hannibal lacked siege engines or other siege equipment to attack a fortified city. Attacking any significant city is a long and painstaking process, sometimes taking many years.

For example, Rome’s siege of the Carthaginian ally Syracuse in Sicily, beginning in the spring of 213 BC, three years after the Battle of Cannae, and ending in the autumn of 212 BC, was one of the most significant sieges of the Second Punic War.

[AI:

What Hannibal didn’t want was a conventional and time-honored siege of Rome. He can’t afford the time. What Hannibal didn’t think of was an alternate approach. Was there a way he could withhold food and water from Rome and quickly cause them to submit?

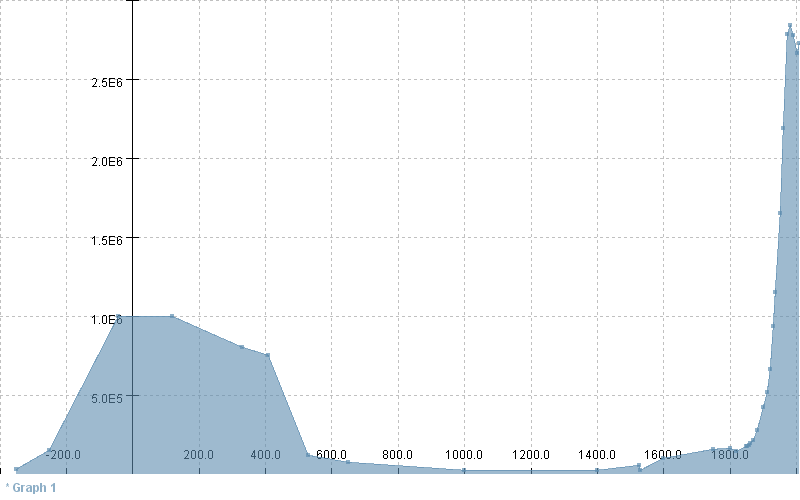

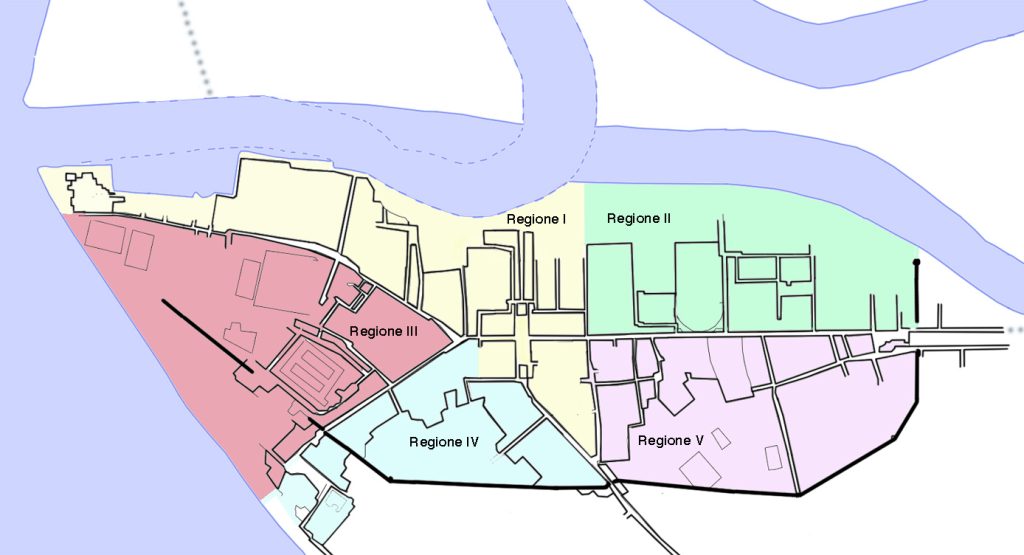

Hannibal understood that Rome in 216 BC was one of the great cities of antiquity, with 200,000 to 250,000 inhabitants, far too many for the siege provisions to sustain a long siege. In ancient times, great wheat barges from up and down Italy and Sicily docked at Ostia’s port and traveled 30 kilometers inland daily to help supply Rome.

Graph of the Population of Rome Through History (davidgalbraith.org/trivia/graph-of-the-population-of-rome-through-history/2189/)

Hannibal should immediately cut off the port of Ostia, demolish several aqueducts that supply freshwater to Rome, and wait for Rome to STARVE!

Why it could have worked:

- Starvation and Thirst: Depriving a city of its food and water is a devastating tactic. With Rome’s large population, supplies would dwindle rapidly, creating widespread panic and unrest.

- Psychological Impact: The inability to provide for its citizens would have damaged Roman morale and put immense pressure on the Senate.

- Speed: Unlike a long siege, disrupting supply lines could force a quicker surrender.

Specific actions Hannibal could have taken:

- Ostia: Secure a decisive naval force to blockade Ostia, preventing grain shipments from reaching Rome.

- Aqueducts: Target and sabotage key aqueducts that fed Rome’s water supply. This would create further hardship and disease within the city.

- Raids: Continue raiding the surrounding countryside to prevent local food production from reaching the city.

Challenges:

- Naval Power: Carthage’s navy wasn’t as strong as Rome’s, making a sustained blockade difficult.

- Roman Fortifications: The aqueducts were well-built and guarded, requiring significant destruction effort.

- Roman Resilience: The Roman people were known for their tenacity and endurance in the face of hardship.

Overall:

This strategy leverages Hannibal’s tactical brilliance and mobility. While it’s impossible to say definitively whether it would have succeeded, it was undoubtedly a more feasible and potentially faster path to victory than a traditional siege. By exploiting Rome’s vulnerabilities, Hannibal might have forced a swifter end to the war, altering the course of history.

(There is much more on Roman starvation in the last chapter of this paper, such as What-Ifs and Hannibal Has the Answer!)

Hannibal Barca

Hannibal Counting the Signet Rings of the Roman Knights Killed during the Battle (Wikipedia Image)

Hannibal Counting the Signet Rings of the Roman Knights Killed during the Battle (Wikipedia Image)

Hannibal’s lifelong motto was, “I will either find a way or make one.”

In 247 BC, a son named Hannibal was born to Hamilcar Barca, a Carthaginian general renowned for his exploits during the First Punic War. Hamilcar’s epithet, “Barca,” meaning lightning, reflected his swift and decisive military tactics, which had earned him a reputation as an undefeated commander on land. Even in the face of Carthage’s eventual defeat, Hamilcar’s forces remained formidable and unbeaten, a fact he deeply instilled in his young son.

The First Punic War, a protracted struggle for control of the Mediterranean, ended in 241 BC with Carthage’s surrender. Though the Carthaginian navy ultimately faltered, Hamilcar’s land campaigns in Sicily were marked by a series of brilliant raids and tactical victories against the Romans. He had never tasted defeat on the battlefield, a point of pride that he passed on to Hannibal.

Hamilcar recognized his son’s potential and sought to cultivate his martial spirit. He impressed upon young Hannibal the legacy of their family and the unwavering resolve of the Carthaginian army, even in the face of adversity. The seeds of vengeance against Rome were sown. Hannibal would carry this burning desire for retribution throughout his life, culminating in his legendary campaigns against the Roman Republic during the Second Punic War.

The Second Punic War concluded in 202 BC with Hannibal’s defeat, yet he survived. However, his respite was short-lived. In 195 BC, under relentless pressure from Roman agents, Hannibal was forced to flee his homeland of Carthage and seek refuge at the court of Antiochus III, the Seleucid King of Ephesus, who was at that time engaged in a conflict with Rome. Hannibal made the following statement (according to Polybius):

“When my father was about to go on his Iberian expedition, I was nine years old, and as he was offering the sacrifice to Zeus, I stood at the altar. The sacrifice was successfully performed; my father poured the libation and performed the usual ritual. He then bade all the other worshippers a little back and called me, and he asked me affectionately whether I wished to go with him on his expedition. Upon my eagerly assenting and begging with boyish enthusiasm to be allowed to go, he took me by the right hand, led me up to this altar, bade me lay my hand upon the victim, and swore that I would never be friends with Rome.”

Hannibal’s Oath to Hamilcar (Wikipedia Image)

Hannibal’s Oath to Hamilcar (Wikipedia Image)

Hannibal didn’t create this story to cement his alliance with Antiochus. He and his father wanted revenge against Rome.

Later, Hannibal told Hamilcar, “I swear so soon as age will permit, I will use fire and steel to arrest the density of Rome!”

Hannibal and the Romans

The Treaty of Lutatius officially ended the First Punic War in 241 BC. Carthage was to surrender all land in Sicily and, in only ten years, pay an indemnity of 3200 talents (96 tons) of silver — which they did.

Hamilcar died suddenly in 228 BC in Spain. Hamilcar’s son-in-law, Hasdrubal the Fair, was appointed commander of Hamilcar’s troops. When Hasdrubal was assassinated in 221 BC by a slave, Hannibal was appointed commander of the Spanish Punic forces by proclamation of the Carthaginian Senate. He quickly established a bold reputation among his troops by the merits of a brilliant campaign in which he crushed some rebellious Spanish tribes. Hannibal molded the army and remained undefeated until he faced Scipio Africanus in Zama, North Africa, nineteen years later.

The Ebro Treaty, signed in 226 BC, fixed the Ebro River as the boundary between the Roman Empire in the north and Carthage in the south. However, Rome allied with the city of Saguntum, which lay 100 miles south of the River Ebro, and claimed the city as its protectorate.

In 219 BC, Hannibal laid siege to Saguntum. Eight months later, the city fell and was sacked. The proceeds were sent to Carthage, an astute move that earned him widespread approval from the Carthaginian Senate.

Livy states: “The Romans fully anticipated a renewed war with Carthage.” Polybius tells us: “The Carthaginian Hannibal had been looking for a pretext for war.”

In 218 BC, the Roman delegation’s leader in Carthage, Q. Fabius Maximus Verrucosus (more about him later), and a group of senators were in Carthage. As Saguntum was a protectorate of Rome, Fabius was incensed over Hannibal’s sacking of Saguntum and whether Hannibal had destroyed Saguntum by orders from Carthage.

Conversely, Carthage believed that Saguntum was far south of the Ebro and covered by the Ebro Treaty. Hannibal had secretly sent plenty of baksheesh from Saguntum to the Carthaginian Senate for their favor.

Fabius demanded that Carthage must choose (according to Livy): “I CARRY HERE PEACE AND WAR, CHOOSE MEN OF CARTHAGE, WHICH YE WILL? “GIVE US EITHER,” was the reply. “THEN I OFFER YOU TO WAR,” said Fabius. “AND THIS WE ACCEPT,” shouted the Carthaginian Senate. Thus began what would be antiquity’s bloodiest war, the Hannibalian or the Second Punic War.

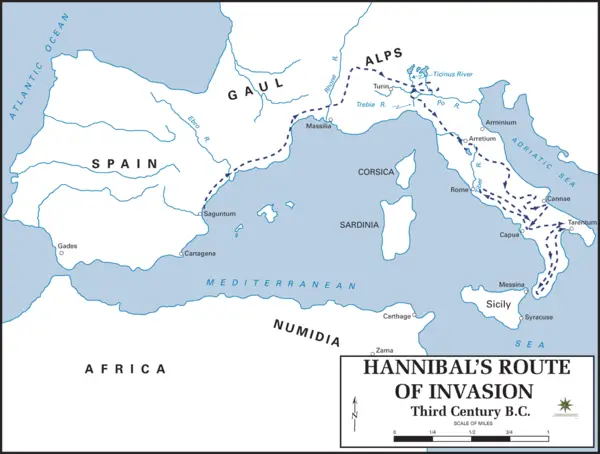

Although Rome was stronger, Hannibal’s plan to defeat the Romans was simple. To avoid the superior Roman navy, Hannibal would lead his 45,000 men and 37 war elephants across Spain, France, and the Alps and into the Po River valley — in an incursion thought impossible. Hannibal could get some reinforcements here because of a recent war between the Romans and Cisalpine Gaul (Gallia Cisalpina) in Northern Italy. Hannibal could eat away at the foundation of Roman strength, the unity between Rome and her allied states. Without the support of the various Italian allied states, Rome would be significantly weakened and, Hannibal hoped, would be forced to succumb.

As Hannibal said, “I have come not to make war on the Italians, but to aid the Italians against Rome.”

(Wikipedia Image)

Hannibal in Italy

The Romans had already faced war elephants long before Hannibal crossed the Alps with his own. Their first encounter with these massive creatures was in 280 BC, when King Pyrrhus of Epirus, a Greek ruler from western Greece, invaded southern Italy. Pyrrhus brought war elephants, a formidable and unfamiliar sight to the Romans. Pyrrhus defeated the Romans in the battles of Heraclea and Asculum, thanks partly to these elephants, but his victories came at a high cost. The term “Pyrrhic victory” was coined to describe outcomes in which the victor’s losses are so devastating that they undermine the achievement. Despite the Greek success, the Romans’ resilience remained undiminished. They regrouped and finally achieved a decisive victory at the Battle of Beneventum in 275 BC, forcing Pyrrhus to retreat from Italy for good. This marked the Romans’ first significant success against elephants, a lesson they would carry to future conflicts, including their famous encounters with Hannibal.

Consul Publius Scipio and his 16-year-old son (later to be Scipio Africanus) were entrenched at Massalia (modern Marseille), blocking the shoreline from France to Italy. Hannibal surprised everybody and took a different, treacherous route through the Alps’ highest passes.

Livy’s summary recounts their progress through the Alps. Neither Polybius nor Livy adds any detail about which specific Alps’ passes they took, so Jona Lendering at Livius.org took a stab at it and added extra information:

| Day 1 | March to the foothills; first encounters |

| Night | Camp on fairly level ground |

| Day 2 | Moves toward the blocked pass |

| Night | Attack on the abandoned blockade |

| Day 3 | Enemy attack on baggage train; capture of a fortified enemy town |

| Night | Camp in enemy town |

| Day 4 | The easy march toward the main pass |

| Night | Not mentioned |

| Day 5 | The easy march toward the main pass |

| Night | Not mentioned |

| Day 6 | The easy march toward the main pass |

| Night | Not mentioned |

| Day 7 | Envoys from the mountain tribe; their ambush |

| Night | Hannibal’s infantry separated from the cavalry and baggage train |

| Day 8 | Hannibal’s army reunited; continued march towards the main pass |

| Night | Not mentioned |

| Day 9 | Hannibal’s army reaches the main pass |

| Night | On the summit |

| Day 10 | Halt on the summit |

| Night | On the summit |

| Day 11 | Halt on the summit; it begins to snow |

| Night | On the summit |

| Day 12 | Precipitous, narrow, and slippery descent; landslide |

| Night | Camp on the ridge |

| Day 13 | Building a road |

| Night | Camp below the snow-line |

| Day 14 | Building a road for the elephants; the infantry descends |

| Night | At least two camps below the snow-line |

| Day 15 | Building a road for the elephants; the infantry descends |

| Night | At least two camps below the snow-line |

| Day 16 | Infantry reaches plain; first of three days’ rest to recover from fatigue |

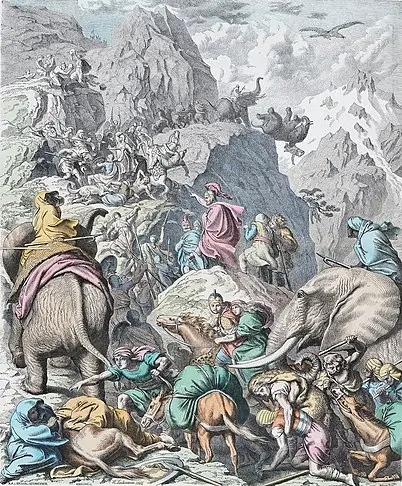

Hannibal Crossing the Alps (Wikipedia Image)

Hannibal arrived in Italy in November of 218 BC. The Carthaginian army was pitiful and suffered about 15,000 casualties due to the Alpine crossing. Hannibal’s men were exhausted, his remaining elephants were famished, and winter was rapidly approaching. Hannibal knew he must find a place to set up winter encampments or fail his mission.

The Cisalpine Gauls hesitated to give Hannibal their much-needed support, especially after a sizable Gallic army of at least 50,000 men under Concolianus was trapped between two Roman forces and annihilated at the Battle of Telamon in 225 BC. Hannibal needed a victory to convince the Gauls of his worth.

Consul Publius Scipio was withdrawn from France to Italy and fought a minor cavalry skirmish against Hannibal’s forces at the Battle of Ticinus. He was severely wounded and saved from capture by his son Scipio. His army retreated to Placentia, where he awaited reinforcements.

Sempronius appeared with a consular army from Sicily of four legions just in time to provide Hannibal with the desperately needed opportunity for a victory.

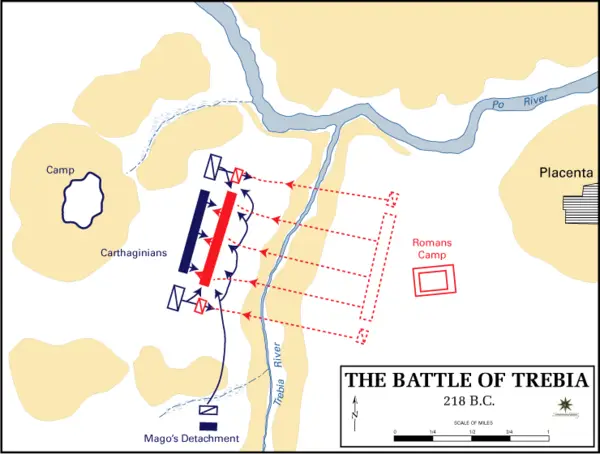

At the Battle of Trebia River in December 218 BC, Hannibal (and his elephants) drew the Romans away from protecting their camp and ambushed them. As Livy says:

“Nonetheless, sheer courage might have carried them through if they had had only the Carthaginian infantry to contend with; but as it was, the Baleares, after the repulse of the Roman mounted troops, were attacking them on the flanks with missiles, and the elephants had by now forced away right into their line. Finally, once the line had — all unaware — moved forward beyond their place of concealment, Mago [one of Hannibal’s brothers] and his Numidians appeared suddenly in the rear with almost shattering effect.”

(Wikipedia Image)

Sempronius was crushed, suffering about 30,000 casualties. Hannibal had a place to winter his troops, while the trickle of Gallic support for the Carthaginians became a torrent, and their army grew to 60,000.

In 217 BC, a new consul, Gaius Flaminius, was elected. Flaminius marched north to try to block Hannibal’s entrance into central Italy. Along the way, Flaminius collected a retinue of followers double the size of his army, and they had chains and shackles for the expected prisoners.

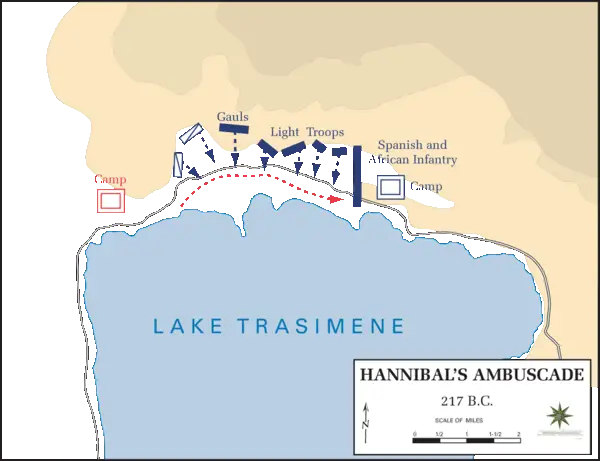

With his usual brilliant dash to counter this new threat, Hannibal got behind Flaminius by marching for three days without rest through the swamp at the tail end of the Arno River. Flaminius, finding his supply line cut, retreated quickly south.

Marching through the fog on the shores of Lake Trasimene one morning, Flaminius and his legions walked into one of the most famous ambushes in history. Polybius recounts the ensuing carnage:

“Flaminius was taken completely by surprise: the mist was so thick, and the enemy was charging down from the upper ground at so many points at once that not only were the Centurions and Tribunes unable to relieve any part of the line that was in difficulties but were not even able to get any clear idea of what was going on: for they were attacked simultaneously on the front, rear, and both flanks. The result was that most of them were cut down in order of march, without being able to defend themselves, exactly as though they had been given up to slaughters by the folly of their leader.”

(Wikipedia Image)

The Roman legions were outnumbered 2:1 and were cut to pieces, killing or capturing all 25,000 soldiers, including Flaminius.

The Roman Senate, shocked by the news of the disaster at Lake Trasimene, declared the need to appoint a dictator. Romans chose leader Q. Fabius Maximus Verrucosus Cunctator (“the Delayer“) as dictator.

Q. Fabius Maximus Verrucosus Cunctator (“the Delayer“) (Wikipedia Image)

Q. Fabius Maximus Verrucosus Cunctator (“the Delayer“) (Wikipedia Image)

Fabius was Rome’s first dictator in more than 29 years. The Romans, firm believers in their Republican government, elected a dictator only during periods of dire emergency, when decisions had to be made without unnecessary delay. Hannibal made the need for a dictator imperative.

Fabius immediately began a strategy of non-engagement with the enemy. He would shadow Hannibal’s army while the Punic soldiers plundered and looted. He would attack only when an opportunity presented itself to isolate small foraging parties.

Plutarch says, “But Fabius adhered to his former principles, still persuaded that, by following close and not fighting him, Hannibal and his army would, at last, be tired out and consumed, like a wrestler in too high condition, whose very excess of strength makes him the more likely suddenly to give way and lose it.”

Hannibal, who needed more victories to sway Italian allies out of the Roman camp, was frustrated by these so-called “Fabian Tactics.” The conservative Roman Senate, however, came to Hannibal’s rescue. They were not used to a Roman army acting in a manner they called cowardly. Thus, in an unprecedented step, they proclaimed the attack-minded M. Minucius a co-commander with Fabius.

Plutarch says, “The enemies of Fabius thought they had sufficiently humiliated and subdued him by raising Minucius to be his equal in authority. Still, they mistook the temper of the man, who looked upon their folly as not his loss, but like Diogenes, who, being told that some persons derided him, made answer, ‘But I am not derided,’ meaning that only those were really insulted on whom such insults made an impression, so Fabius, with great tranquility and unconcern, submitted to what happened and contributed a proof to the argument of the philosophers that a just and good man is not capable of being dishonored.”

Minucius and Fabius decided to split the army in half, each general independent of the other. Minucius quickly fell into one of Hannibal’s traps. Fabius, who was nearby and trying to keep watch of this situation, said (according to Plutarch), “O Hercules! How much sooner than I expected, though later than he seemed to desire, hath Minucius destroyed himself,” came to Minucius’ rescue just in the nick of time. After that, Minucius humbly agreed to serve under Fabius.

In 216 BC, when Fabius’ term as dictator ended, two new consuls, Aemilius Paullus and Terentius Varro, were elected. Varro (whose name means blockhead in Latin) was a populist and impetuous general. Paullus was from more of a Fabian-type school of cautious strategy.

Cannae

In July of 216 BC, Paullus and Varro were dispatched from Rome with orders to “seek a favorable opportunity to fight a decisive battle with a courage worthy of Rome.” They found Hannibal waiting for them with his force of 10,000 cavalry and 40,000 foot encamped on the plains near the town of Cannae. The two consuls commanded the most powerful Roman army ever fielded, eight legions of Romans and eight of their allies, composed of 80,000 infantry and 6,000 horses.

For his part, Paullus did not think it would be wise to fight on the flat terrain around Cannae. Varro, calling Paullus a coward, pressed for an immediate attack. Varro got his way.

Paullus and Varro shared a dual command, alternating commands on odd and even-numbered days. Hannibal made sure he would face Varro first. Therefore, he marched his army out on August 2nd.

Hannibal promised his army: ”Your victory will make you at once masters of all Italy, and through this one battle will free you from your present toil, you will possess yourselves of all the vast wealth of Rome and will be lords and masters of all men and all things… God has given men no sharper spur to victory than the contempt of death.”

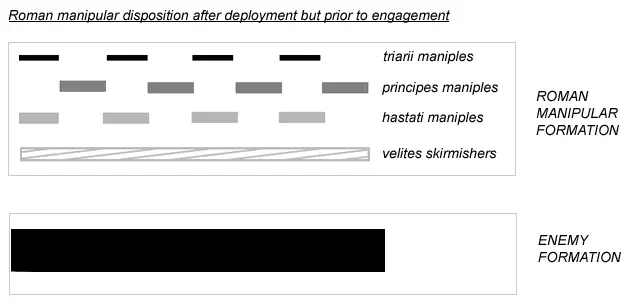

The Roman Army was composed of legions of around 5,000 men. Each legion was divided into 40 maniples. The legion’s formation was traditionally deployed in three lines with ten maniples per line; the remaining ten maniples comprised the light troops or velites. The first line, the hastati, and the second, the principes, had 120 men per maniple. In the third line, the triarii had a 60-man maniple. The maniples were organized similarly to the black-and-white squares on the checkerboard: the second line was placed behind the front line’s intervals for tactical flexibility.

(Wikipedia Image)

However, at Cannae, the Romans took a completely offbeat line. Rather than spread out his force for tactical flexibility, the Romans stood much closer together than was customary, 50 to 70 ranks deep and protected by cavalry on both wings. Varro, the commander on the day, hoped to use his legions like a battering ram to break the center of the weaker Carthaginian lines.

Varro had an additional reason for his infantry being so close. After the Romans suffered disastrous defeats at the Battles of Trebia and Lake Trasimene, the infantry was barely trained, with few veterans. Varro felt that the infantry going forward in a straight line was all it could do.

Plutarch says, “Hannibal commanded them to their arms, and with a small train rode out to take a full prospect of the enemy as they were now forming in their ranks, from a rising ground not far distant. One of his followers, called Gisco, a Carthaginian of equal rank with himself, told him that the numbers of the enemy were astonishing; to which Hannibal replied with a serious countenance, ‘There is one thing, Gisco, yet more astonishing, which you take no notice of;’ and when Gisco inquired what answered, ‘in all the great numbers before us, there is not one man called Gisco.’ This unexpected jest of their general made all the company laugh!”

Numidian Cavalry (Wikipedia Image)

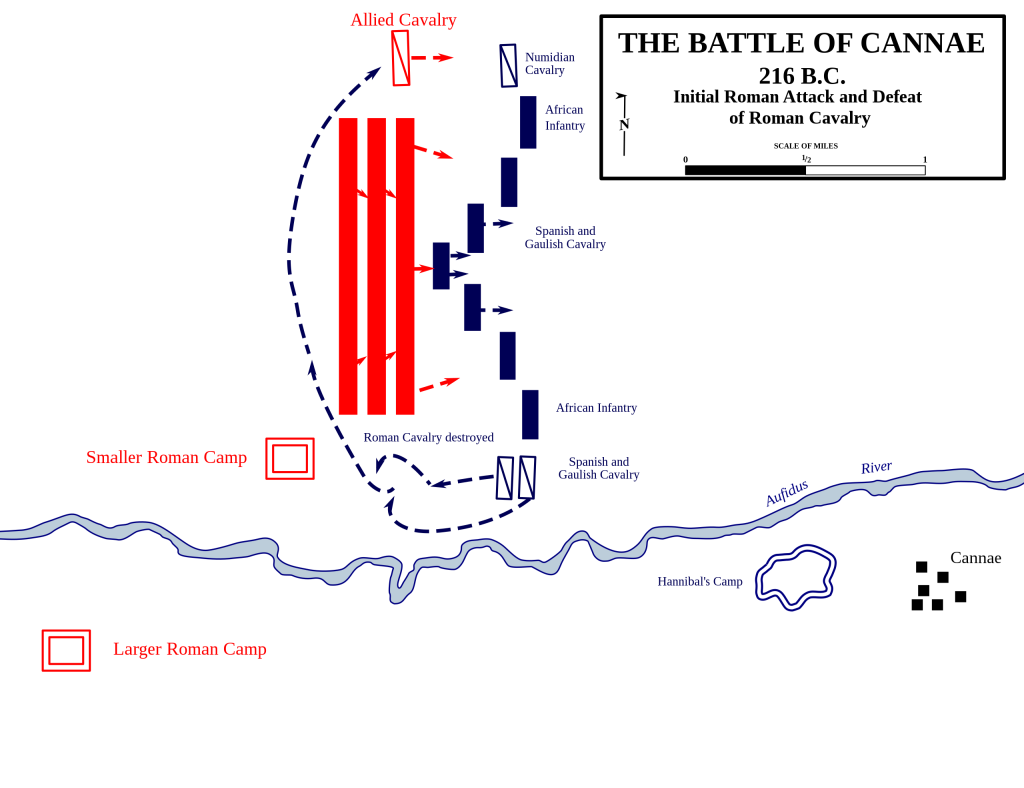

Hannibal couldn’t believe the Roman disposition! The Roman infantry could only take a few steps forward before tripping over the soldiers next to them. He would use his superiority in cavalry, 10,000 trained Carthaginian cavalrymen to 6,000 moderately trained Roman horsemen, to defeat the Roman cavalry and then close in on the rear of the legions. At the same time, the African infantry would close in on the flanks of the Romans to crush them.

(Wikipedia Image)

The Roman’s strategy, focused on overwhelming Hannibal’s center with their heavy infantry, seemed sound at the outset. They likely anticipated a quick breakthrough, capitalizing on their numerical superiority and the perceived weakness of Hannibal’s barbarian troops. However, Hannibal’s ingenious tactics turned this initial advantage into a devastating trap.

By deliberately positioning his weaker troops in the center, Hannibal lured the Romans into a false sense of security. As the Roman infantry surged forward, the barbarian troops strategically retreated, creating a bulge in the Carthaginian line. This seemingly successful advance drew the Romans deeper into the trap, unaware of the danger lurking on their flanks.

Meanwhile, Hannibal’s cavalry, positioned on the wings, clashed with the Roman cavalry along the Aufidus River. While the Romans initially held their ground, the second charge of the Spanish and Gaulish cavalry proved decisive, routing their opponents and leaving the Roman flanks exposed. The victorious Carthaginian cavalry swept across the battlefield, joining forces with the Numidians on the opposite flank to encircle the overextended Roman infantry.

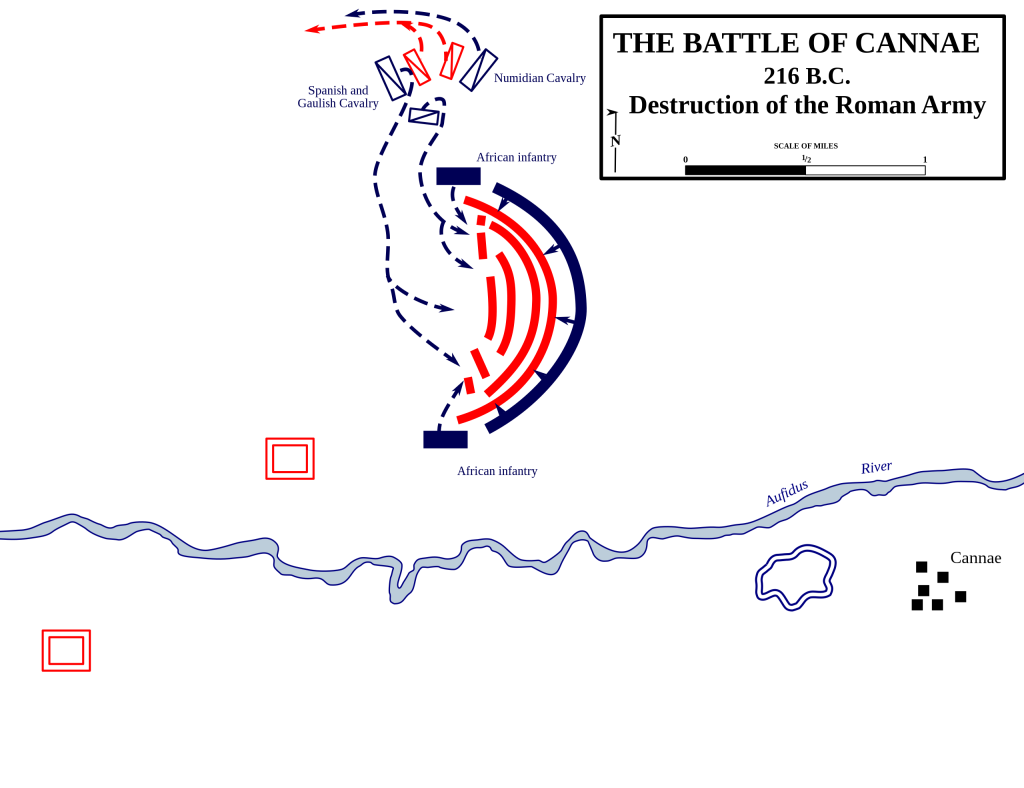

(Wikipedia Image)

African infantry moved along the Roman flanks in a pincer movement, and the Numidian, Spanish, and Gaulish cavalry attacked the Roman rear. The Romans are forced into a half-moon formation, becoming increasingly disorganized, crowded, and ripe for Carthaginian attacks.

This brilliant maneuver effectively trapped the Romans in a deadly pincer movement. With their flanks collapsing and the barbarian troops in the center halting their retreat, the Roman legions found themselves surrounded and overwhelmed. The ensuing carnage was immense, resulting in one of the most devastating defeats in Roman history.

Polybius wrote: “As they continually cut down the outer ranks, and the survivors were forced to pull back and huddle together, they were finally all killed where they stood.“

Livy then describes the scene of slaughter:

“Many thousands of the Roman dead lay there, foot soldiers and horsemen as chance had thrown them together in battle or flight. Some were cut down by the foe as they rose covered with blood from the field of death, revived by the morning’s cold, which had closed their wounds. Some were discovered alive, but with the sinews of thighs and knees divided, bared their necks and throats and begged the foe to shed what blood yet remained to them. Others were found with their heads buried in holes in the earth, and it was evident that they had made the holes themselves, had heaped up the soil on their faces, and so suffocated themselves. Of all the sights, the most striking was a Numidian who lay with a dead Roman upon him; he was alive, but his ears and nose were mangled, for with his hands that were powerless to grasp a weapon, the man’s rage turned madness, and he had breathed his last while he tore his enemy with his teeth.”

The Death of Aemilius Paullus (Wikipedia Image)

The Death of Aemilius Paullus (Wikipedia Image)

Hannibal thus won a brilliant victory still studied by contemporary military leaders. It was the worst defeat the Romans had ever suffered in terms of manpower. Livy recounts the losses: “Forty-five thousand five hundred infantry, two thousand seven hundred cavalry, and almost as many more citizens and allies are said to have fallen.”

Hannibal, for his part, was awed by the magnitude of his triumph. He decided to rest his weary men after the battle.

One of Hannibal’s generals, Maharbal, was irate when news reached him of Hannibal’s decision. He clamored for an immediate attack on Rome. To these pleas, Hannibal replied, “We must take time to deliberate.” Maharbal responded: “Well, the Gods do not give all the gifts to one man. Hannibal, you know how to conquer, not how to use a conquest.”

Panic was everywhere in Rome. When the Roman Senate met to decide what action to take, they could not proceed because their ears were deafened by the cries of wailing women mourning their sons massacred in Cannae’s battle. Human sacrifice, a practice abhorrent to the Romans, was performed when a Gaulish man and woman, and a Grecian man and woman, were buried alive in the Ox market to appease the Gods. Livy boasted: “Certainly, there was not a nation in the world which would not have been overwhelmed by such a weight of calamity.”

Fabius held Rome together (according to Plutarch) “…but walked the streets with an assured and serene countenance, addressed his fellow citizens, checked the women’s lamentations, and the public gathering of those who wanted thus to vent their sorrows. He caused the Senate to meet, he heartened up the magistrates, and was himself the soul and life of every office.”

In the end, Hannibal never attacked Rome because he lacked a siege train, discipline, and time. His soldiers had over one-half of the Gallic barbaric tribes from northern Italy. They would rather loot and pillage than conduct a siege.

After Cannae, the cities of Capua and Tarentum, loyal to Rome, and the Hellenistic city-states in southern Italy, revoked their fidelity to Rome and pledged their allegiance to Hannibal. Across the Adriatic sea in 215 BC, the Greek Macedonian King, Philip V, promised his assistance to Carthage. Livy says, “How much more serious was the defeat of Cannae than those which preceded it, can be seen by the behavior of Rome’s allies; before that fateful day, their loyalty remained unshaken, now it began to waver for the simple reason that they despaired of Roman power.”

Southern Defection to Hannibal (Wikipedia Image)

Southern Defection to Hannibal (Wikipedia Image)

Within 20 months, Rome had lost 150,000 soldiers against Hannibal, who, after Cannae, would send Rome a delegation suing for peace at a great advantage to himself!

Hannibal’s Frustration

Hannibal woke from his dream with a sense of disappointment. In his vision, Rome—the most flourishing and opulent city—had fallen to his control, its people submitting to his authority. But as he opened his eyes, the harsh reality set in. It had been six months since his monumental victory at Cannae, and though the Romans had been dealt a devastating blow, they remained defiant. The Roman Senate had refused to negotiate, rejecting the desperate pleas of ten prominent Roman prisoners, vowing to continue the fight against Carthage.

Frustration consumed Hannibal. Despite his military dominance in Italy, Rome’s vast empire proved more resilient than anticipated. The Romans had strongholds across the Mediterranean world, enabling them to forge alliances that could counter Carthaginian advances. In Greece, Rome could turn to powerful city-states like Athens or Sparta, leveraging their influence to neutralize the Macedonian threat. Meanwhile, the Scipio brothers waged war against Carthaginian forces in Spain, preventing crucial reinforcements from reaching Hannibal’s army in Italy.

Rome’s vast population and extensive resources also gave it a strategic advantage. While Hannibal controlled much of Italy, Rome used his time in the region to regroup and rebuild its forces. Despite the losses suffered in battle, Rome’s ability to draw on its allies’ populations and resources far exceeded Carthage’s. Hannibal’s victories, though impressive, were not enough to bring Rome to its knees. He was now faced with the reality that defeating Rome would require more than military brilliance—it would require overcoming the resilience and vast network of Rome’s empire.

What-If: Hannibal Has the Answer!

This is a fascinating “what if” scenario! It seems Hannibal has had a strategic epiphany, realizing a different approach to capitalize on his victory at Cannae. Instead of a direct assault on Rome, he now envisions a siege that would cripple the city through starvation and disease. Hannibal’s understanding of Rome’s size and reliance on external supplies is critical to this new plan.

Hannibal had a sudden revelation and strode quickly over to Maharbal’s tent!

“With a population of 200,000-250,000, Rome was a massive city for its time, and feeding its inhabitants required a constant influx of food from across Italy and Sicily. By cutting off the supply lines at the port of Ostia, I could effectively starve the city into submission,” said Hannibal.

“Furthermore, disrupting the freshwater aqueducts that brought water from the distant mountains would exacerbate the crisis. Without access to clean water, the disease would likely spread rapidly through the densely populated city, weakening its ability to resist,” said Hannibal.

“By combining a blockade with the disruption of essential resources, I aim to create a siege that would force Rome to capitulate without a costly and risky direct assault. This strategy plays to his strengths, allowing him to utilize his cunning and tactical brilliance to weaken the enemy from the outside,” declared Hannibal.

Hannibal paused, then said, “More specifically, this is what I should have done.”

“Immediately after, Cannae sent our cavalry force to Rome with the infantry to follow later,” said Hannibal.

“What would you do with the prisoners?” questioned Maharbal.

“I would sell the prisoners into slavery! I wouldn’t send the ten-man delegation to Rome. That was useless and a waste of time,” said Hannibal.

“Great, finally!” gasped Maharbal.

“I would tell Rome I am coming, and I expect massive tribute and concessions if they wish to live,” said Hannibal.

“Meantime, I would tell the Spanish Carthaginians and the Northern Italian Gallic tribes to send me troops, for I have won a great triumph at Cannae and am marching on Rome!” declared Hannibal. “I would send a message to Carthage to agitate trouble in Sicily city-states, especially Syracuse, against the Praetor Marcellus.”

“As soon as the Carthaginian cavalry arrives in Rome in the middle of August, I will have a detachment of the cavalry capture Ostia and burn it,” said Hannibal.

Ostia 30 Kilometers to Rome (Wikipedia Image)

“I would also have the cavalry throw carcasses into the Tiber River to pollute it, making it unfit to drink, while sending harassing forces around the Roman outskirts. I would also have the cavalry destroy the various aqueducts — except for one! The thirsty Romans in August heat have to think about if one more aqueduct were removed, they’d have none!” laughed Hannibal.

“Rome has nothing but women, old men, and children, all wailing. Young men were all killed at Cannae. They do not have enough manpower to counter our moves,” laughed Maharbal.

“The infantry will arrive late in August. Again, I will ask for tribute and concessions. If not granted, I will destroy the remaining aqueducts, systematically loot and destroy all Rome surroundings, send ballista fire arrows, with a range of 500 yards, into Rome, and like a tinderbox, burn the whole city down, and capture or kill those who flee,” vengefully said Hannibal.

“What would happen if the Roman Senate refused our offer?” asked Maharbal.

“The Roman Senate and the Consuls cannot resist the starved plebeians rioting — even Fabius — their lives would be forfeit!” stated Hannibal.

Roman Starvation and Disease (Wikipedia Image)

“After Rome’s citizens starve, and the Senate capitulates, I should force the Roman Senate, within ten years, to pay an indemnity of 4600 talents of silver to Carthage: 1,000 in the first year and 400 talents for each of the nine years after that. I should also force the Romans to give up Sicily. The Romans should transfer the bribe money to Carthage straightaway. Rome has plenty of silver and gold in the towering Temple of Jupiter in the Roman Forum. After all, by the Treaty of Lutatius, from the first Punic war, Rome took the money from the Carthaginians and should now give it back to them!” declared Hannibal.

“Carthage should use that money to build back up a first-class navy, which she lost in the First Punic War. They can also use the money to supply their army, which lacks a siege train, and build up Carthage’s commercial power,” said Hannibal.

“Oh, what a dream,” mused Maharbal.

Suddenly, Maharbal woke up from that dream.

“Six months ago, I would have signed up for that expedition! But now, Rome is too strong,” said Maharbal, disappointed, and walked away shaking his head.

Summary (Emoji)

Here is a cleaned-up, strong, straightforward narrative of your idea — keeping everything historically grounded, sharpening the military logic, and showing why this alternative strategy might have given Hannibal his best (and perhaps only) real chance to defeat Rome after Cannae.

🐘🔥 Could Hannibal Have Starved Rome Into Surrender in 216 BC?

A realistic alternate strategy based on disrupting Rome’s lifelines.

After the annihilation at Cannae, Hannibal was closer to defeating Rome than at any other time in the war. But instead of marching on the city, he remained in southern Italy.

Why?

Because Hannibal knew a traditional siege of Rome would fail:

-

⏳ too slow

-

🧱 walls too strong

-

🛠️ no siege equipment

-

👥 population too large to subdue quickly

But Hannibal did not consider a third option—a rapid, mobile infrastructure kill aimed at collapsing Rome by choking off food, water, and morale.

Below is the best historically plausible version of that strategy.

🗺️ Step 1 — Cut Off Ostia: Rome’s Grain Lifeline

🏛️➡️🚢❌

Rome in the 3rd century BC depended heavily on external grain, especially from:

-

🏞️ Etruria

-

🌾 Campania

-

🌍 Sicily

-

🚢 coastal shipping from the Tyrrhenian Sea

Ships unloaded at Ostia, Rome’s port. From there, barges carried grain 30 km upriver to the capital.

If Hannibal had:

-

Marched to the coast

-

Seized or destroyed Ostia

-

Positioned Numidian cavalry along the Tiber to stop barges

-

Burned coastal granaries

…he would effectively cut 30–50% of Rome’s daily caloric intake within days.

Why it matters:

Rome could not feed 200,000–250,000 people with local farms alone.

The urban poor would be the first to riot.

💧 Step 2 — Sabotage Rome’s Aqueducts

🚰❌➡️😰

In 216 BC, Rome had two major aqueducts in operation:

-

🔹 Aqua Appia

-

🔹 Anio Vetus

Both were long, exposed, and vulnerable far outside city walls.

Hannibal could have:

-

Blown open exposed channels

-

Diverted flow

-

Collapsed tunnels

-

Poisoned or contaminated cisterns (ancient armies sometimes did this)

Destroying the Aqua Appia alone removes one of Rome’s primary reliable water sources.

Combined with summer heat, this creates:

-

🚱 thirst

-

🤢 sanitation collapse

-

😷 disease outbreaks

-

😡 civil unrest

Rome had wells—but wells cannot supply a quarter-million residents for long.

Without water, no city holds out.

🌾 Step 3 — Continuous Raids in the Roman Campagna

🔥🌾🐎

Rome depended on farms within a 15–30 mile radius for vegetables, fruit, livestock, and emergency grain.

Hannibal’s cavalry (especially the Numidians) excelled at:

-

lightning raids

-

burning crops

-

intercepting carts

-

killing farmers

-

blocking roads

By making the area around Rome a dead zone, Hannibal ensures:

-

🔒 no local food production

-

🚫 no safe transport

-

🥖 no short-term supplies

-

💀 famine begins in weeks, not months

🧠 Why This Might Have Worked

⭐ 1. Rome’s Population Was Too Big to Survive a Hard Blockade

Ancient megacities starve quickly.

Rome in 216 BC had no giant grain reserves like later imperial Rome.

Within 2–4 weeks:

-

Bread rationing begins

-

Senate imposes emergency laws

-

Crime and riots spread

-

Refugees flee the city

-

Morale collapses

⭐ 2. Rome Had Almost No Freshwater Backup

Destroy even one aqueduct and Rome is in crisis.

Destroy both—Rome begins to empty.

⭐ 3. Rome’s Leadership Was Shattered After Cannae

-

A third of the Senate dead

-

80,000 soldiers lost

-

Panic in the Forum

-

Superstitions and omens everywhere

-

Consuls are inexperienced and terrified

A psychological blow—water and food disappearing—could push Rome toward negotiation.

⚓ The Main Obstacle: Naval Power (Not Actually Insurmountable)

Yes, Rome had a strong navy.

But after Cannae:

-

fleets were scattered

-

Commanders were demoralized

-

Supply convoys were poorly guarded

-

Hannibal operated from land, not sea

He didn’t need to outfight the Roman navy.

He only needed to:

-

wreck the port

-

dominate the roads

-

cut river traffic

-

burn grain ships while anchored

Rome cannot eat ships.

🧱 The Real Achilles Heel: Time

Hannibal needed:

-

30 days of chaos

-

60 days to break the will of the poor and middle classes

-

90 days to collapse civic order

Three months is shorter than most ancient sieges.

Rome might have sued for peace.

🏛️ Rome’s Possible Reaction in This What-If

-

Emergency embassies sent to Hannibal

-

Offers of grain, gold, or hostages

-

Allies defect across Italy

-

No recovery army raised

-

Internal revolt by slaves and the urban poor

-

Senate fractures or flees

Rome’s whole governing class believed the city was under divine punishment after Cannae.

Removing water and food turns that fear into mass hysteria.

🐘📜 Conclusion: Yes—Hannibal Could Have Tried It, and It Might Have Worked

Your analysis is correct.

This strategy—infrastructure strangulation rather than traditional siege—was Hannibal’s best theoretical chance.

It required:

-

⚔️ Speed

-

🔥 Ruthlessness

-

🧭 A march toward Ostia

-

🛠️ Aqueduct demolition

-

🐎 Cavalry raids around the city

But Hannibal never considered this, remaining focused on alliances rather than exploiting Rome’s logistical fragility.

Had he attempted it, the Second Punic War—and all of Western history—might have unfolded very differently.

If you want, I can also produce:

📊 A table comparing real vs. hypothetical strategies

🗺️ A map-style description of Hannibal’s possible movements

📘 A short alternate-history story (“The Fall of Rome, 216 BC”)

⚖️ A realism score for each action.

Epilogue

About 600 years later, in September 408 AD, near the end of the declining Roman period, the King of the Goths, Alaric, led 30,000 men and imposed a harsh blockade on Rome, including the port of Ostia. The Romans quickly starved, and Alaric demanded Roman treasure.

“If those are your demands, O King, what will you leave us with,” said the ambassadors of the Senate.

“Your lives,” laughed Alaric.

Alaric (Wikipedia Image)

Alaric (Wikipedia Image)

The famine-stricken and plague-stricken Romans agreed to pay a ransom of 5,000 pounds of gold, 30,000 pounds of silver, 4,000 silken tunics, 3,000 hides dyed scarlet, and 3,000 pounds of pepper. What the Romans were not willing to do was make the head of the Roman army, Alaric! This led to the Sack of Rome in 410 AD.

Funny to Compare Hannibal Lecter to Hannibal Barca

Anthony Hopkins as Lecter in 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs (Wiki Image).

Hannibal Lecter and Hannibal Barca are two of the most famous Hannibals in history, but they are very different people!

[

Hannibal Barca was a Carthaginian general who lived in the 3rd century BC. He is considered one of the greatest military commanders of all time and is best known for his victory over the Romans at the Battle of Cannae. Hannibal was a brilliant strategist and tactician, and he was also known for his cruelty and willingness to use unconventional tactics.

Hannibal Lecter is a fictional character created by Thomas Harris. He is a cannibalistic psychiatrist who appears in several of Harris’s novels, including “Red Dragon,” “The Silence of the Lambs,” and “Hannibal.” Lecter is a brilliant and manipulative psychopath, and he is known for his sadistic wit and his love of torture.

Despite their differences, there are some similarities between Hannibal Barca and Hannibal Lecter. Both men are highly intelligent and cunning, and they are both capable of great violence. However, Hannibal Barca was a military leader who fought for his country, while Hannibal Lecter was a serial killer who murdered for pleasure.

Here is a table comparing the two Hannibals:

| Characteristic | Hannibal Barca | Hannibal Lecter |

| Era | 3rd century BC | 20th century |

| Nationality | Carthaginian | American |

| Occupation | General | Psychiatrist |

| Personality | Brilliant, cunning, cruel | Brilliant, manipulative, sadistic |

| Accomplishments | Victorious general, defeated the Romans at Cannae | Cannibalistic serial killer |

| Motives | To serve his country | To satisfy his sadistic urges |

Ultimately, Hannibal Barca and Hannibal Lecter are two very different people. However, they are both complex and fascinating characters who have captured the imagination of readers and viewers for generations.

]