Napoleon Bonaparte is Green, M. de Bourrienne is Royal Blue, and others are Brundt Orange.

Prologue: Introducing M. de Bourrienne

M. de Bourrienne reflects in his Memoirs of Napoleon Bonaparte, “I had known Napoleon since his boyhood at the school in Brienne, and our unreserved intimacy continued the most brilliant part of Napoleon’s career…I not only had the opportunity of being present at the conception and the execution of the extraordinary deeds of one of the ablest men nature ever formed, but, notwithstanding an almost unceasing application to business, I found means to employ the few moments of leisure which Bonaparte left at my disposal in making notes, collecting documents, and in recording for history facts respecting which the truth could otherwise with difficult be ascertained; and more particularly in collecting these ideas, often profound, brilliant, and striking, but always remarkable, to which Bonaparte gave expression in the overflowing frankness of confidential intimacy.”

Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne (Wikipedia Image)

Introduction; 1812

Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812, often called the Russian Campaign or the Patriotic War of 1812, was a turning point in the Napoleonic Wars and one of the most disastrous military campaigns in history. His objective was to force Tsar Alexander I to cease trading with Britain and enforce the Continental System.

On 24 June 1812, the Grande Armée crossed the Niemen into Russia. Napoleon pushed his army of 422,000 soldiers in an attempt to destroy the separated Russian troops. Unfortunately, the Russian armies recombined. Under their new commander, Mikhail Kutuzov, the Russians began their slow, over 500-mile retreat to Moscow, dwindling over half of Napoleon’s forces. Kutuzov decided to make a stand at Borodino, just outside Moscow.

Napoleon and his staff at Borodino (Wikipedia Image)

Napoleon and his staff at Borodino (Wikipedia Image)

The Russians and French took fearful casualties at the Battle of Borodino, and Napoleon won a pyrrhic victory. Napoleon took Moscow and found it deserted!

Kutuzov, on the far left, with his generals at the talks, decided to surrender Moscow to the French (Wikipedia Image)

Kutuzov, on the far left, with his generals at the talks, decided to surrender Moscow to the French (Wikipedia Image)

To quote from Tolstoy’s War and Peace, “To study the skillful tactics and aims of Napoleon and his army from the time it entered Moscow till it was destroyed is like studying the dying leaps and shudders of a mortally wounded animal.”

Napoleon tried to contact Tsar Alexander I, but the Tsar refused to answer. Moscow burned (nobody knows who started it). Thus, Napoleon began the long retreat in the merciless cold of Moscow. Napoleon invaded Russia with about 422,000 soldiers. At the end of the winter, only 10,000 were left.

Napoleon’s withdrawal from Russia (Wikipedia Image)

Napoleon’s withdrawal from Russia (Wikipedia Image)

Below is the famous graphic by Charles Minard that illustrates the extreme toll the march and the temperature took on the lives of Napoleon’s army.

(Wikipedia Image)

Haunted by the catastrophic Russian campaign, Napoleon, in his St. Helena exile, pondered a turning point: what if, at Tilsit in 1807, following his decisive victory at Friedland, he had leveraged his power to force Czar Alexander I to abolish serfdom in exchange for Poland? The resulting social and economic upheaval within Russia would have likely crippled its ability to wage war, potentially preventing the 1812 invasion and altering the course of European history.

Serfdom was a system of forced labor that bound peasants to the land and their masters. It could have been a more efficient system, which would have prevented the Russian economy from developing. If the Russians had been forced to abolish serfdom, they would have had to invest heavily in education and infrastructure to modernize their economy. This would have required time and resources, making it difficult for them to engage in war or trade.

Russia traded with England, and as England controlled the seas and blocked France and its possessions, Napoleon’s empire suffered economic harm. Russia was the last leading trading partner in Europe, after England. Halting trade would bring England closer to negotiating a peace treaty with Napoleon.

In 1807, Napoleon had a unique opportunity to cripple the Russian Empire and, indirectly, England. If he had leveraged his victory at Tilsit to force Alexander I to abolish serfdom, the consequences for Russia could have been devastating.

The sudden liberation of millions of serfs would have triggered immense social and economic upheaval. Land redistribution, labor shortages, and resistance from the nobility would have disrupted agricultural production and the entire Russian economy. This chaos would have severely limited Russia’s ability to trade, both internally and externally, effectively cutting off a significant source of income for the British.

With Russia’s trade diminished, England would have lost a crucial market and source of raw materials. This economic blow, coupled with the ongoing Continental Blockade, could have weakened England to the point where it would be forced to seek peace with Napoleon. This strategic maneuver, though risky and potentially destabilizing, could have secured Napoleon’s dominance over Europe and brought an end to the Napoleonic Wars.

Napoleon, Son of the Revolution?

Napoleon and Ney at the Battle of Friedland in 1807 (Wikipedia Image)

Napoleon and Ney at the Battle of Friedland in 1807 (Wikipedia Image)

The utterance of “Napoleon Bonaparte” sends a blurred series of images sweeping involuntarily before one’s eyes. Cannons are raking masses of colorfully clad troops. The drum roll. Screams! Shouted commands! The din of battle! An undaunted figure mounted on a white stallion. A face painted with the stare of supreme confidence, lack of doubt, and victory!

Napoleon was a man committed to his righteousness who would tolerate no dissent. He had a definite opinion of the way things should be. He owed his allegiance not to France’s revolution, not any man or state, but to himself!

Napoleon was no “Son of the Revolution.” If the revolutionary ideals of Marat, Danton, and Robespierre coincided with his thoughts, they were accepted; yet, if they in any way went against the grain of Napoleon’s ideology, they were rejected. Napoleon attempted to revive France’s glories with rationalization, not doctrine.

Napoleon in 1820

The year is 1820, and the place is St. Helena, a desolate island in the South Atlantic. I, M. de Bourrienne, am finally granted permission to see my old friend, Napoleon Bonaparte, after years of separation. The anticipation is overwhelming as I am ushered into his garden. It is a moment I have longed for, yet nothing could prepare me for the scene that unfolds before my eyes.

I see a man who once commanded the armies of Europe, now a shadow of his former self. Illness has ravaged him. His once-proud bearing is stooped, his face etched with pain. The symptoms I knew too well from his earlier years have worsened: the bouts of vomiting, the agonizing stomach pains, and the inability to keep food down.

But it is not just the physical decline that shocks me. It is the sight of Napoleon, the one-time conqueror, reduced to playing childish games on a seesaw with his companions. This is not the Emperor I remember, the man of boundless energy and ambition. This is a broken man, seeking solace in simple pleasures, his spirit as diminished as his body.

A wave of sadness washes over me. I am witnessing the final act of a once-great tragedy.

On the other hand, I recall in my Memoirs, “It is crucial not to lose sight of the premature decay of his health [Napoleon], which, perhaps, did not always permit to process the vigor of memory otherwise consistent with his age.”

Napoleon at St. Helena (Wikipedia Image)

Napoleon at St. Helena (Wikipedia Image)

I saluted Napoleon. Napoleon stood up, stern and ardent. His silk shirt and trousers were out of uniform, but he was inevitably wearing his iconic and illustrious hat.

He exclaimed, “At Tilsit in 1807, I may have made one mistake. I should have made the Russians abolish serfdom or give the land back to Poland!”

Napoleon put his hands behind his back and started pacing back and forth.

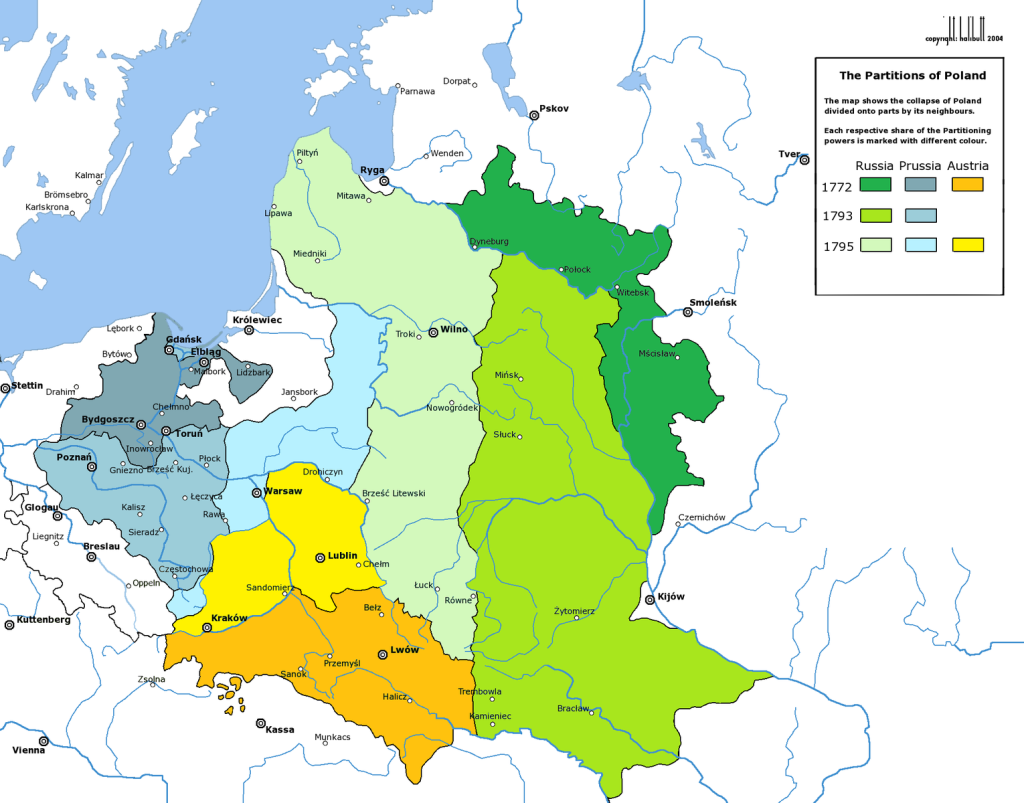

“In 1770, Poland stood as a proud and expansive nation, symbolized by its majestic white eagle soaring freely across vast lands. However, its strength and independence were soon to be tested by the rapacious appetites of its powerful neighbors. Austria, Prussia, and Russia, likened to “three black eagles,” cast their covetous eyes upon Poland’s territory!” declared Napoleon.

“Driven by insatiable greed, these empires seized the opportunity presented by Poland’s internal weaknesses. In a series of three partitions, they systematically devoured Poland’s lands, leaving the once-mighty nation dismembered and erased from the map of Europe. Once a symbol of national pride, the white eagle was tragically eclipsed, its wings clipped, and its spirit crushed. The partitions marked a dark chapter in Polish history, a testament to the ruthless nature of power politics and the devastating consequences of imperial ambition,” said Napoleon.

The Partitions of Poland (Wikipedia Image)

The Partitions of Poland (Wikipedia Image)

“In 1807, at the Treaty of Tilsit, Napoleon had considerable leverage after his European victories. He successfully forced Austria and Prussia to return much of the Polish territory they had annexed. However, in hindsight, Napoleon recognizes that, instead of focusing solely on territorial adjustments, he could have used his influence to push Tsar Alexander I and the Russian nobility to abolish serfdom. Napoleon believes that if he had addressed the deep-rooted social inequalities in Russia by advocating for the repeal of serfdom, it could have alleviated tensions between France and Russia, potentially preventing the disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812. This reflection highlights a critical turning point where diplomatic strategy might have changed the course of history!” exclaimed Napoleon.

Exhausted, Napoleon excused himself from the party and said, “M. de Bourrienne, wake me up in the morning, and I will carry on with my story.”

M. de Bourrienne thought, “Like his favorite poet Ossian, who loved best to touch his lyre midst the howlings of the tempest, Napoleon required political tempests to display his abilities.”

Napoleon walked back to the house and went to bed.

Interlude: Countess Marie Walewska

Countess Marie Walewska (Wikipedia Image)

M. de Bourrienne awakened Napoleon in the morning. Napoleon had vomited. I helped Napoleon out of bed, dressed him, and led him into the garden. Napoleon looked refreshed and continued with his story.

“I had won the third coalition war against the Austrians and the Russians at Austerlitz’s decisive battle in 1805, which forced Austria, however, not the Russians, out of the war. In 1806, I fought the fourth coalition war against Prussia, Russia, Sweden, and Great Britain, which was just a continuation of the previous war,” recounted Napoleon.

“We won at the Prussian battle of Jena and Auerstedt in October. I won the battle of Jena, and at the same time, over 10 miles away, my compatriot Field Marshal Louis-Nicolas Devout won the battle of Auerstadt — a dual battle! I pursued the Prussians to Berlin with the cavalry, and the Prussians were decisively beaten,” said Napoleon with satisfaction!

“I arrived in Warsaw, which I loved. I loved it because this was the most intense place for the revolution outside France!” exclaimed Napoleon. “Poles would fill out my army. I named it the Grand Duchy of Warsaw.”

“A chance meeting with the lovely Countess Marie Walewska left a lasting impression on me. Her sandy hair and creamy complexion were captivating, and I found myself instantly smitten. The spark of attraction ignited a flame of passion within me, and I fell deeply in love,” voiced Napoleon.

“Despite the knowledge of her marriage to a much older man, my heart remained undeterred. Age and societal constraints held no sway over the intensity of my feelings. In that moment, all that mattered was the undeniable connection I felt with Marie, a love that would defy convention and leave an indelible mark on my life,” said Napoleon.

Napoleon explained, “When she was much younger, Joséphine married Alexandre de Beauharnais and had two lovely children, Eugène and Hortense. Unfortunately, her husband was guillotined in 1794. She married me in 1796, but she was barren and unable to give me an heir. She said, ‘Go out, find a beautiful girl, and tell me.’ Josephine was married to the Emperor of France and knew how important it was for me to have some offspring to rule France.”

Joséphine Bonaparte (Wikipedia Image)

“When I approached Marie to have an amorous liaison, I was frustrated: Marie Walewska said, ‘The knot which has been tied on earth can only be untied in heaven,’’’ said Napoleon.

“After countless times of rejection, I spoke up, ‘Marie, I have revived the name of your country. It still exists, thanks to me. And I will do much more than this! But just remember that like this watch that I hold in my hands, which shatters at your feet — its name will perish. And so will all your hopes perish if you drive to extremes by rejecting my heart and refusing me yours,’” asserted Napoleon.

Declared Napoleon, “I wanted to impress her. If the Poles received back all the Polish land from the Austrians and Prussians, she would have to receive me!”

Marie Walewska (Greta Garbo) and Napoleon (Charles Boyer) (Wikipedia Image)

“Marie did not run away; then, in 1809, she followed me to Vienna. She lived with me at the Schonbrunn Palace, became pregnant, and gave birth to a son, Alexandre Joseph!” said Napoleon with pride.

“I remember in 1814 when I was on the Isle of Elba, Marie and my four-year-old son Alexandre came to visit me. I played hide-and-seek with the boy. I said to Alexandre, ‘I hear you don’t mention my name in your prayers.’ He admitted he didn’t mention Napoleon, but remembered to say ‘Papa Empereur,’” laughed Napoleon.

“I told Marie, ‘He’ll be a great social success, this boy: he’s got wit,’” said Napoleon.

“Marie Walewska was the only loving woman who visited me on the Isle of Elba. She died in 1817,” said Napoleon sadly.

Napoleon and M. de Bourrienne smiled and hugged each other. Napoleon was sleepy and retired to his chambers.

M. de Bourrienne thought, “Napoleon committed to sorrow, love, and glory swifter than anyone I have seen.”

Events leading to the Treaty of Tilsit, Russian Fourth Coalition

The following day, Napoleon looked much better. Napoleon had a thoughtful look and began to reminisce about the conclusion of the fourth coalition campaign, which led to the Treaty of Tilsit.

“My adversary is Russian General Levin August von Bennigsen. The German entered service in 1773 under Catherine the Great and forged a reputation in the Polish campaign, where he became commander of the Russian forces. I kept chasing him from Warsaw to the north before catching him at Eylau in early February of 1807,” said Napoleon.

General Levin August von Bennigsen (Wikipedia Image)

General Levin August von Bennigsen (Wikipedia Image)

“Bennigsen had 67,000 Russian troops and 400 guns, while I had only 49,000 troops and 300 guns. I decided to attack with Augereau’s VII Corps in the center. The blizzard obscured Augereau’s troop advance, and he ran into seventy Russian cannons. The attack was a disaster. Bennigsen counterattacked. The French center was in great disorder for four hours,” pronounced Napoleon.

Battle of Eylau (Wikipedia Image)

Battle of Eylau (Wikipedia Image)

“One must engage in battle only when one has no new opportunities for which to hope, since by its nature the fate of a battle is always doubtful, but once it has been resolved upon, one must conquer or perish,“ said Napoleon.

“I had one reserve — the 11,000 French cuirassier cavalry! In one of the greatest cavalry charges in history, greater than the charge of Alexander’s Companions at Gaugamela against Darius III, I ordered Joachim Murat to advance!” declared Napoleon.

Joachim Murat (Wikipedia Image)

Joachim Murat (Wikipedia Image)

“He broke through the Russian infantry. He broke through the Russian cavalry. He broke through the Russian cannons. And then he went back and broke the Russian infantry once again!” exclaimed Napoleon.

“That is my Napoleon,” thought M. de Bourrienne. “Nothing related to a man like Napoleon can be considered useless or trivial. He stands as straight as the arrow for a man his age and likes facts, figures, and GLORY better than anything else!”

French Cavalry Charge (Wikipedia Image)

French Cavalry Charge (Wikipedia Image)

“I was about to win when the 9,000 Prussians came to the field late in the day, and I was forced to regroup,” said Napoleon.

“Quel massacre! Et sans résultat. (What a massacre! And without result),” quoted Napoleon from Marshal Ney.

“The French took 22,000 casualties, and the Russians took 21,000 losses,” recounted Napoleon.

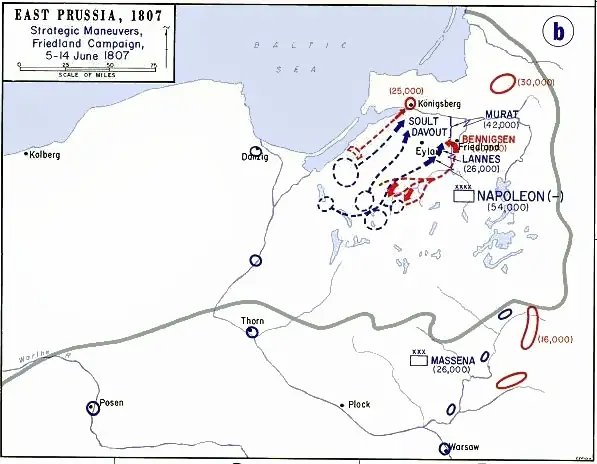

Napoleon Leading Up to the Battle of Friedland (Wikipedia Image)

“I determined to trap the Russians with superior forces: 190,000 versus 115,000 soldiers. I went to Konigsberg in early June, expecting the Russians to be at hand. Far out on the right flank was the corps of Marshal Jean Lannes. He found the entire Russian army out there, marching upon the opposite end of the Alle River near Friedland,” said Napoleon.

“Ride with your horse into the ground if you have to, but tell the Emperor we’re fighting the entire Russian army!” quoted Napoleon on a dispatch from Marshal Lannes.

“Bennigsen decided to attack Lannes across the Alle River. At night, he built three pontoon bridges across the Alle River, and the Russians crossed. Lannes fought a rearguard action against Bennigsen. Bennigsen, late in the evening, should have gotten the army out of there, but the Russians stayed,” asserted Napoleon.

“I arrived, and I had 80,000 troops versus 55,000 Russian soldiers. Surprised, I said, ‘We won’t catch the enemy making a mistake like this twice.’ I decided to launch an attack upon the Russians at 5:30 pm. The Russians broke and ran down to the Alle River, which blocked their retreat, and an unknown number died from drowning,” said Napoleon.

“The Russian army suffered dreadful casualties at Friedland — losing over 40% of its soldiers,” said Napoleon.

Thought M. de Bourrienne, “‘He throws his army on the enemy like an unloosed torrent,’ yet Marshal Lannes died in Austria in 1809, and most of the Field Marshals and men, especially during the Russia Campaign of 1812. That is the downside of glory!”

Treaty of Tilsit

Napoleon and Alexander I at Their Meeting at Tilsit (Wikipedia Image)

Napoleon and Alexander I at Their Meeting at Tilsit (Wikipedia Image)

“In the wake of their crushing defeat, the Russians were compelled to seek a truce. We agreed to meet on neutral ground, the center of the Neman River at Tilsit, on June 25, 1807. I meticulously prepared two grand pavilions to set the stage for this historic encounter. Adorned with a single eagle, one was designated for Alexander I, the Tzar of all Russia. The other, proudly displaying the French eagle, was reserved for me,” said Napoleon.

“My intention was clear: to impress the young Tzar. Alexander I was a relatively new ruler, and I sought to showcase France’s might and grandeur. The pavilions, symbols of our respective nations, were to serve as a visual reminder of the power dynamics at play. The meeting at Tilsit was not merely a negotiation of peace terms but also a diplomatic performance, a stage upon which I intended to assert my dominance and secure a favorable outcome for France,” said Napoleon.

“The eagles’ symbolism was not lost on anyone. The Russian eagle, solitary and somewhat subdued, reflected their recent defeat. In contrast, the French eagle, proud and defiant, symbolized the victorious French Empire. This visual display was a subtle yet powerful message to the young Tzar, a reminder of the consequences of challenging my authority and a prelude to the following negotiations.” declared Napoleon.

“The sound of a hundred cannons went off from the Russians in tribute. I met Alexander as he stepped into the boat. We greeted each other and embraced,” said Napoleon.

“‘I hate the English as much as you do yourself,’” said Napoleon, quoting Alexander I.

“If that is the case, then peace is already made,“ voiced Napoleon.

Napoleon and Alexander I (Wikipedia Image)

“The Russians and I got to real business in their secret clauses. Russia would have Turkey’s European holdings and Finland; eastern Poland would remain under Alexander I, and he would participate in the Continental Blockade against England, which remained at war with France. I would have Spain, Portugal, and Western Poland. Prussia would receive the worst punishment; French troops would occupy until Prussia paid 120 million francs,” said Napoleon.

“Perhaps I was happiest at Tilsit… I found myself victorious, dictating laws, having emperors and kings pay me to court,“ said Napoleon.

Napoleon’s Wishful Thinking

Napoleon was silent.

M. de Bourrienne interjected into the silence, “I want to ask you about yesterday when you said, ‘Abolish serfdom or give the land back to Poland.’ I want you to continue, here, in 1820, what you, Napoleon, would have done versus Alexander I — that day in 1807 at Tilsit!”

Napoleon, using his insight and inventiveness, imagined a conversation with Alexander I:

Napoleon to Alexander:

“There’s another thing to add to the treaty: freedom for all the serfs. All the world, currently enslaved, including black slaves, would see what a great deed for humanity I am commanding! Marat, Danton, and Robespierre were all unified in wanting slavery abolished. I will do it and be the Son of the Revolution for all the world to see!”

Alexander replies to Napoleon:

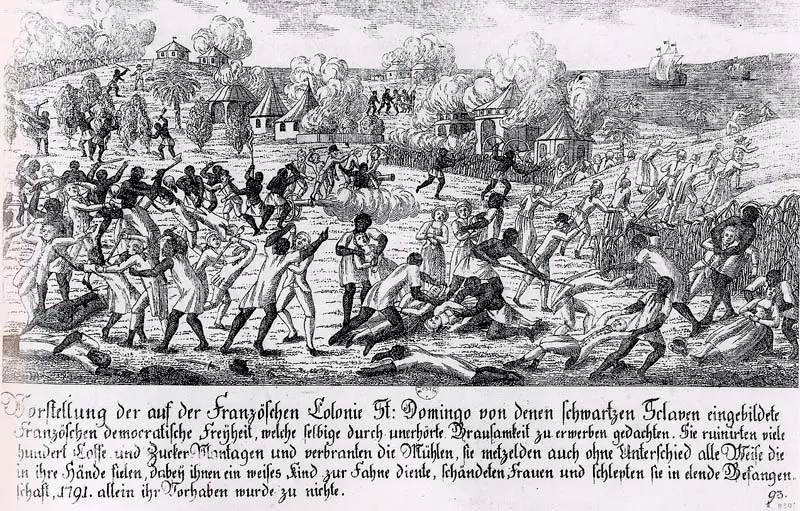

“What about the French Slavery Act of 1802, revoking the law passed in 1794 that had abolished slavery in the French colonies? What about the 20,000 troops you sent to the Caribbean on the Island of Saint-Domingue [west Haiti] to re-enslave 600,000 free Africans formerly enslaved?”

The Saint-Domingue slave revolt in 1791 was led by Toussaint L’Ouverture (Wikipedia Image)

The Saint-Domingue slave revolt in 1791 was led by Toussaint L’Ouverture (Wikipedia Image)

Napoleon replies to Alexander:

“That was my mistake. I had to reverse position. Saint-Domingue became well-known as the ‘Pearl of the Antilles’ — one of the world’s richest colonies. Saint-Domingue produced about 60 percent of Europe’s coffee and 40 percent of its sugar. When the slaves were freed, the cost was enormous. I have since recovered from that act and intend to outlaw slavery from all of France’s laws. I will put it in the Tilist Treaty.”

Alexander replies to Napoleon:

“What about the Russian Nobles? They won’t like to liberate the serfs.”

Russian Nobles, or Boyar (Wikipedia Image)

Napoleon replies to Alexander:

“If you do not abolish serfdom, Russia must relinquish Polish lands taken in 1772, ‘95, and ‘98. This man, after all, had his family, his happiness, and his liberty, and it was a horrible act of cruelty to bring him here to languish in the fetters of slavery!”

Finally, after thinking, Alexander replies to Napoleon:

“Well, I did create a new civil tier of free farmers in 1803 for serfs to be voluntarily liberated by their masters. I now say, free all the Russian serfs!”

Serfs and Their Master (Wikipedia Image)

Serfs and Their Master (Wikipedia Image)

“Bravo, Bravo,” said M. de Bourrienne.

Napoleon looked irritated!

“Marat, Danton, and Robespierre — I don’t care what they say!” exclaimed Napoleon.

“So you tricked Alexander I in your imagination,” said M. de Bourrienne, laughing.

“If I had brought this to fruition, I could have avoided the long, costly war with Russia in 1812,” declared Napoleon.

Napoleon relaxed, then clarified, “Twenty million Russian serfs gain the freedoms of citizens, including the right to own businesses and property. Thanks to the French, the serfs get their freedom — which they should never forget!”

Russian serfs listening to the proclamation of the Emancipation Manifest (Wikipedia Image)

Russian serfs listening to the proclamation of the Emancipation Manifest (Wikipedia Image)

Napoleon paused and said, “But by my design, this will disrupt Russia to my benefit. On the downside for Russia, I will speculate what will happen:

- Thanks to the Nobles, the rural free serfs will be given less farmland than they need to survive—my guess is one-half. The free serfs will protest, and they want a much larger share than that. The nobles will refuse, and famine will strike Russia.

- The urban serfs from household staff will be most adversely affected, as they will gain no land, be penniless, and, if they lose their household jobs, need crown subsistence to survive.

- Wealthy Nobles had tens of thousands of serfs. Russian serfs were forced to work and live on the land provided to them by their Nobles. This is similar to the French system before the Revolution. Russian serfs provided barshchina, a term for corvée in France, and paid obrok, a term for taille in French. Barshchina was labor dues, meaning that for a certain number of days per week, serfs were compelled to work the plow or dig up potatoes or wheat for their overseer rather than themselves. Obrok was the land tax on serfs’ land, paid to the Nobles. The former system of compulsory labor will be abolished. A new system must be implemented, or civil unrest will be inevitable.

- Those Nobles who led the reform will favor democracy with all that free land, and a capitalist economic system will develop; some will be reactionary and not want change. This will cause a civil war.

- Serfdom was necessary due to military conscription. The conscripted serfs were the vast majority of the Russian military. The newly freed serfs would resist joining the military, especially with the army’s harsh discipline and brutal treatment. They would demand equal treatment with citizens, including equal pay. The other problem is that the Russians would be unable to pay for an equivalent-sized military due to disruptions in cash flow following the serfs being freed.”

Napoleon summarizes:

“Serfs granted freedom will take one generation to sort out. I will have a free run over Europe for the next twenty years. The War of 1812 against Russia and the Grande Armée’s destruction in the frigid winter months will never happen. Russia’s problems with the serfs will make invasion unnecessary!”

“I see, vividly, le Monsieur Bonaparte,” said M. de Bourrienne. “I see how freeing the serfs will prevent the War of 1812 against Russia!”

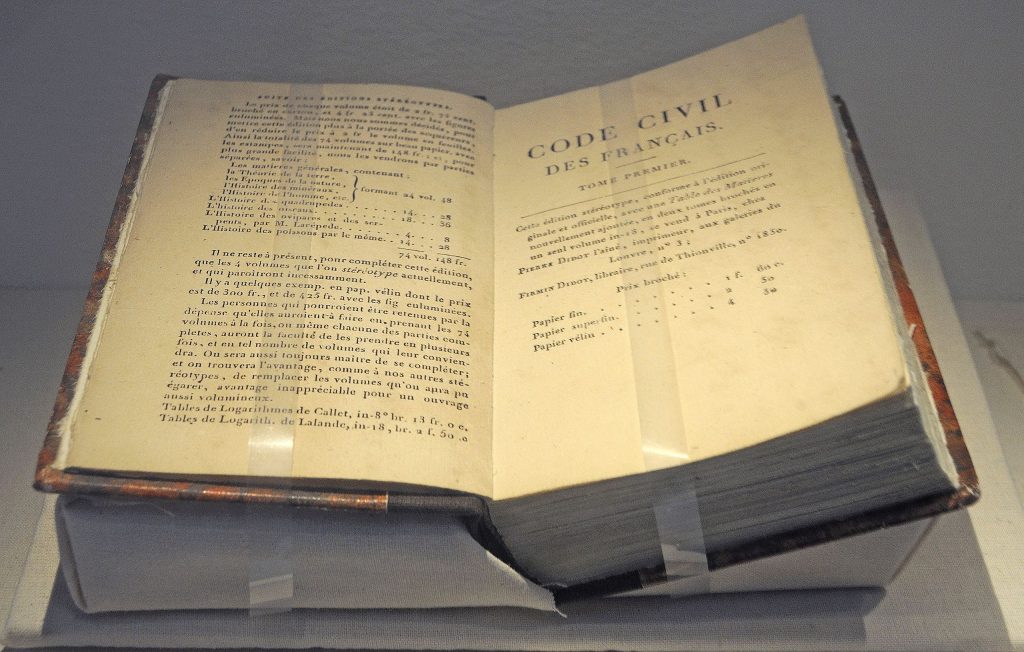

Then Napoleon said, “I will make peace with the British. Then, I can concentrate on my Civil Code of France (Code Civil des Français), the Napoleonic Code, a different code than the Old Regime’s feudal law. I can spread that throughout Europe. That will live forever long after my victories.“

Civil Code of the French (Code Civil Des Francais) (Wikipedia Image)

Civil Code of the French (Code Civil Des Francais) (Wikipedia Image)

M. de Bourrienne thought, “He owed his allegiance, not to the revolution, France, any man or state, but Napoleon!”

Napoleon bowed and returned to his house under British guard on St. Helena.

Summary (Emoji)

Here is your scenario expressed in a clean, emoji-rich, dramatic style, while keeping all the historical logic intact:

🇫🇷⚔️👑 Napoleon’s “Missed Masterstroke” at Tilsit (1807)

What if Napoleon forced Alexander I to abolish serfdom—ten years early?

🌊🐎💥 Context: Friedland & Tilsit — Napoleon at Peak Power

After the crushing French victory at Friedland, Napoleon met Tsar Alexander on the raft at Tilsit (1807).

Historically, Napoleon took Poland-neutralizing concessions and an uneasy alliance.

But—

🤯❗ What if he had demanded something far more radical?

Immediate abolition of Russian serfdom, in exchange for Poland and a diplomatic partnership.

🧨🇷🇺 1. Social Explosion: Ten Million Serfs Freed Overnight

Serfdom = peasants legally tied to land and lord (essentially agricultural bondage).

If abolished in 1807:

🚜📉 Agriculture collapses

-

Landowners lose their workforce.

-

Peasants gain freedom but not tools, land rights, or mobility infrastructure.

-

Grain output plummets.

-

The empire’s main export (grain → Britain) evaporates.

🔥👑 Nobility revolts

The Russian aristocracy, already suspicious of Alexander’s French flirtations, would view this as:

“The Emperor has become Napoleon’s puppet.”

Possibilities:

-

Assassination attempts

-

Palace coups

-

Civil unrest on a massive scale

🧠📚 Forced modernization

Abolition would require:

-

A new tax system

-

New labor markets

-

New industrial investments

-

Education reforms

Russia in 1807 was not ready for this.

They barely survived the actual 1861 emancipation—and that had 50 years of debate behind it.

🔗🚢🇬🇧 2. Russia’s Trade with Britain Collapses

Britain was the last primary European market Napoleon couldn’t cut off.

Russia exported:

-

Grain

-

Timber

-

Hemp & tar (critical for British naval rope and shipbuilding)

❌🌾 With agriculture in chaos, Russia can’t export.

❌⛵ Britain loses vital supplies for the Royal Navy.

This puts enormous pressure on London, already strained by:

-

The Continental System

-

The costly Peninsular War

-

Mounting national debt

🇫🇷🤝🇷🇺 3. Napoleon Now Has the Leverage to Force British Peace

Removing Russia from the anti-French economic sphere was exactly Napoleon’s grand strategy.

If Britain loses:

-

Russian grain

-

Russian naval supplies

-

Russian markets

Then the British blockade becomes much more vulnerable.

🇬🇧💸 Britain might be forced to negotiate an early peace.

Napoleon wins without invading Russia.

No 1812 campaign.

No retreat from Moscow.

No collapse of the Grand Armée.

⚔️❄️🔥 4. No 1812 Catastrophe → The Napoleonic Empire Survives?

With Russia crippled by internal turmoil, Napoleon would never need to march into the disaster of 1812.

He avoids:

-

The destruction of his veteran army

-

Loss of European allies

-

Rise of anti-French coalitions

-

Invitation for Prussia & Austria to rebel

🏛️🌍 The Napoleonic Order in Europe might have lasted decades.

🧩📜 5. But… could Napoleon have forced Alexander?

This is the key uncertainty.

Alexander, I feared:

-

Social revolution

-

Nobility backlash

-

Being seen as a “French-style” reformer

-

Another Pugachev-style peasant uprising

He might have:

-

Refused

-

Delayed

-

Signed but never implemented

-

Used it as a diplomatic excuse to later betray Napoleon (as he did historically)

Even so, Napoleon in 1807 had maximum leverage:

He could have demanded the impossible.

🎭🔮 Conclusion: A Very Plausible Turning Point

This counterfactual is historically rich because:

✔ Economically plausible

Abolition in 1807 would shatter Russia’s rural economy.

✔ Strategically devastating

Britain loses its last major European trade partner.

✔ Politically explosive

Alexander I risks losing his throne.

✔ Militarily decisive

The 1812 invasion—the fatal blow to Napoleon—never happens.

🎖️🗺️ Result:

Napoleon’s empire might survive in the long term, reshaping 19th-century Europe entirely.

If you’d like, I can create:

-

🌍 A map-style emoji summary

-

📝 A “timeline of the alternate 1807–1830 world.”

-

⚖️ A comparison to the actual Emancipation of 1861

-

🧠 A Napoleon-on-St-Helena monologue about this scenario

Just tell me!